Forrest Gump

| Forrest Gump | |

|---|---|

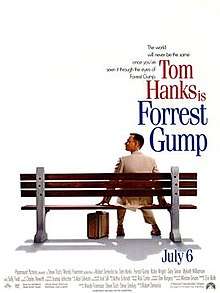

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Robert Zemeckis |

| Produced by | |

| Screenplay by | Eric Roth |

| Based on |

Forrest Gump by Winston Groom |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Alan Silvestri |

| Cinematography | Don Burgess |

| Edited by | Arthur Schmidt |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 142 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $55 million[1] |

| Box office | $677.9 million[1] |

Forrest Gump is a 1994 American romantic comedy-drama film based on the 1986 novel of the same name by Winston Groom. It was directed by Robert Zemeckis and written by Eric Roth, and stars Tom Hanks, Robin Wright, Gary Sinise, Mykelti Williamson, and Sally Field. The story depicts several decades in the life of Forrest Gump (Hanks), a slow-witted but kind-hearted man from Alabama who witnesses several defining historical events in the 20th century in the United States.

The film differs substantially from the novel. Principal photography took place in late 1993, mainly in Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. Extensive visual effects were used to incorporate Hanks into archived footage and develop other scenes. The soundtrack features songs reflecting the different periods seen in the film.

Released in the United States on July 6, 1994, Forrest Gump received favorable reviews for Zemeckis' directing, Hanks' performance, visual effects, and script. The film was a massive success at the box office; it became the top-grossing film in North America released that year and earned over US$677 million worldwide during its theatrical run, making it the second highest-grossing film of 1994. The soundtrack sold over 12 million copies. Forrest Gump won the Academy Awards for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor for Hanks, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Visual Effects, and Best Film Editing. It won many other awards and nominations, including Golden Globes, People's Choice Awards, and Young Artist Awards.

Varying interpretations have been made of the protagonist and the film's political symbolism. In 1996, a restaurant based on the film, Bubba Gump Shrimp Company, opened, and has since expanded to locations worldwide. In 2011, the Library of Congress selected the film for preservation in the United States National Film Registry as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[2]

Plot

In 1981, Forrest Gump recounts his life story to strangers who sit next to him on a bench at a bus stop in Savannah, Georgia.

On his first day of school in Greenbow, Alabama in 1954, Forrest meets a girl named Jenny Curran who, unlike the other children, immediately befriends him. Due to leg braces fitted to correct a curved spine, Forrest is unable to walk properly. One day, a young truck driver stays at the boarding house that Forrest lives in with his mother. The young truck driver turns out to be Elvis Presley, who, while playing guitar for him, becomes enthralled at the jerky hip thrusting movements that the hobbled Forrest makes while trying to dance. Later on, Elvis becomes famous by imitating the dance.

Forrest is often bullied because of his physical disability and marginal intelligence. One day, while trying to escape some bullies chasing him, his braces fall off revealing the young Forrest to be a very fast runner. Jenny yells to him, "Run, Forrest, run!" Despite his low intelligence quotient, Forrest's new running ability leads to him receiving a football scholarship to the University of Alabama in 1963, becoming a top running back, being named on the All-American team, and meeting President John F. Kennedy. After his college graduation, he voluntarily enlists in the U.S. Army, where he befriends a fellow soldier named Bubba, who convinces Forrest to go into the shrimping business with him when the war is over. In 1967, they are sent to Vietnam and, during an ambush, Bubba is killed in action. Forrest saves many of his platoon, including his lieutenant, Dan Taylor, who loses both his legs. Forrest is awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroism.

While Forrest is in recovery for a gunshot wound to his buttocks received while saving his platoon-mates, he develops a talent for ping pong. He becomes a ping pong celebrity and plays competitively against Chinese teams in ping pong diplomacy. At an anti-war rally in Washington, D.C., Forrest briefly reunites with Jenny, who has been living a hippie lifestyle. While in D.C. in 1972, Forrest meets president Richard Nixon and is put up in the Watergate hotel, where he accidentally reveals the Watergate scandal, ultimately forcing Nixon to resign.

Returning home, Forrest endorses a company that makes ping pong paddles. He uses the earnings to buy a shrimping boat, fulfilling his promise to Bubba. Taylor joins Forrest in 1974, they initially have little success. After their boat becomes the only one to survive Hurricane Carmen they pull in huge amounts of shrimp. They use their income to purchase a fleet of shrimp boats. Dan invests the money in Apple Computer (which Forrest naïvely thinks is "some kind of fruit company") and Forrest is financially secure for the rest of his life but gives half of his earnings to Bubba's family. He then returns home to see his mother's last days.

In late 1978, Jenny returns to visit Forrest, and he soon proposes to her. She declines but slips into his bedroom and makes love to him that night before leaving early the next morning. Heartbroken, Forrest goes running. He decides to keep running across the country several times over three and a half years, becoming famous in the process.

In the present, Forrest reveals that he is waiting at the bus stop because he received a letter from Jenny who, having seen him run on television, asked him to visit her. Reunited with Jenny, she introduces him to his son, named Forrest Gump, Jr. Jenny tells Forrest she is sick with an unknown virus. The three then move back to Greenbow. Jenny and Forrest finally marry but she dies a year later. Forrest and his son await the school bus on Forrest Jr.'s first day of school.

Cast

- Tom Hanks as Forrest Gump: Though at an early age he is deemed to have a below average IQ of 75, he has an endearing character and shows devotion to his loved ones and duties, character traits which bring him into many life-changing situations. Along the way, he encounters many historical figures and events throughout his life. Tom's younger brother Jim Hanks is his acting double in the movie for the scenes when Forrest runs across the U.S. Tom's daughter Elizabeth Hanks appears in the movie as the girl on the school bus who refuses to let young Forrest (Michael Conner Humphreys) sit next to her. John Travolta was the original choice to play the title role and admits passing on the role was a mistake.[3][4][5] Bill Murray and Chevy Chase were also considered for the role.[6] Sean Penn stated in an interview having been second choice for the role. Hanks revealed that he signed on to the film after an hour and a half of reading the script.[7] He initially wanted to ease Forrest's pronounced Southern accent, but was eventually persuaded by director Robert Zemeckis to portray the heavy accent stressed in the novel.[7]

- Michael Conner Humphreys portrayed the young Forrest Gump. Hanks revealed in interviews that after hearing Michael's unique accented drawl, he incorporated it into the older character's accent. Winston Groom, who wrote the original novel, describes the film as having taken the "rough edges" off of the character, and envisioned him being played by John Goodman.[8]

- Robin Wright as Jenny Curran: Forrest's childhood friend with whom he immediately falls in love, and never stops loving throughout his life. A victim of child sexual abuse at the hands of her bitterly widowed father, Jenny embarks on a different path from Forrest, leading a self-destructive life and becoming part of the hippie movement in the 1960s and the 1970s/1980s drug culture. She re-enters Forrest's life at various times in adulthood. Jenny eventually becomes a waitress in Savannah, Georgia, where she lives in an apartment with her (and Forrest's) son, Forrest Jr. They eventually get married, but soon afterward she dies from complications due to an unnamed disease.

- Hanna R. Hall portrayed the young Jenny.

- Gary Sinise as Lieutenant Dan Taylor: Forrest and Bubba Blue's platoon leader during the Vietnam War, whose ancestors have died in every U.S. war and who regards it as his destiny to do the same. After losing his legs in an ambush and being rescued against his will by Forrest, he is initially bitter and antagonistic towards Forrest for leaving him a "cripple" and denying him his family's destiny, falling into a deep depression. He later serves as Forrest's first mate at the Bubba Gump Shrimp Company, gives most of the orders, becoming wealthy with Forrest, and regains his will to live. He ultimately forgives and thanks Forrest for saving his life. By the end of the film, he is engaged to be married and is sporting "magic legs" – titanium alloy prosthetics which allow him to walk again.

- Mykelti Williamson as Benjamin Buford "Bubba" Blue: Bubba was originally supposed to be the senior partner in the Bubba Gump Shrimp Company, but due to his death in Vietnam, their platoon leader, Dan Taylor, took his place. The company posthumously carried his name. Forrest later gave Bubba's mother Bubba's share of the business. Throughout filming, Williamson wore a lip attachment to create Bubba's protruding lip.[9] David Alan Grier, Ice Cube and Dave Chappelle were all offered the role but turned it down.[6][10] Chappelle said he believed the film would be unsuccessful, and also acknowledged that he regrets not taking the role.[6]

- Sally Field as Mrs. Gump: Field reflected on the character, "She's a woman who loves her son unconditionally. … A lot of her dialogue sounds like slogans, and that's just what she intends."[11]

- Haley Joel Osment as Forrest Gump, Jr.: Osment was cast in the film after the casting director noticed him in a Pizza Hut commercial.[12]

- Peter Dobson as Elvis: Although Kurt Russell was uncredited, he provided the voice for Elvis in the scene.[13]

- Dick Cavett as himself: Cavett played a version of himself in the 1970s, with makeup applied to make him appear younger. Consequently, Cavett is the only well-known figure in the film to play a cameo role rather than be represented through the use of archival footage like John Lennon or President John F. Kennedy[14]

- Sonny Shroyer as Coach Paul "Bear" Bryant

- Grand L. Bush, Michael Jace, Conor Kennelly, and Teddy Lane Jr. as the Black Panthers

Production

Script

—director Robert Zemeckis[15]

The film is based on the 1986 novel by Winston Groom. Both center on the character of Forrest Gump. However, the film primarily focuses on the first eleven chapters of the novel, before skipping ahead to the end of the novel with the founding of Bubba Gump Shrimp Co. and the meeting with Forrest, Jr. In addition to skipping some parts of the novel, the film adds several aspects to Gump's life that do not occur in the novel, such as his needing leg braces as a child and his run across the United States.[16]

Gump's core character and personality are also changed from the novel; among other things his film character is less of a savant — in the novel, while playing football at the university, he fails craft and gym, but receives a perfect score in an advanced physics class he is enrolled in by his coach to satisfy his college requirements.[16] The novel also features Gump as an astronaut, a professional wrestler, and a chess player.[16]

Two directors were offered the opportunity to direct the film before Robert Zemeckis was selected. Terry Gilliam turned down the offer.[17] Barry Sonnenfeld was attached to the film, but left to direct Addams Family Values.[18]

Filming

Filming began in August 1993 and ended in December of that year.[19] Although most of the film is set in Alabama, filming took place mainly in and around Beaufort, South Carolina, as well as parts of coastal Virginia and North Carolina,[7] including a running shot on the Blue Ridge Parkway.[20] Downtown portions of the fictional town of Greenbow were filmed in Varnville, South Carolina.[21] The scene of Forrest running through Vietnam while under fire was filmed on Fripp Island, South Carolina.[22] Additional filming took place on the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina, and along the Blue Ridge Parkway near Boone, North Carolina. The most notable place was Grandfather Mountain where a part of the road is named "Forrest Gump Curve".[23] The Gump family home set was built along the Combahee River near Yemassee, South Carolina, and the nearby land was used to film Curran's home as well as some of the Vietnam scenes.[24] Over 20 palmetto trees were planted to improve the Vietnam scenes.[24] Forrest Gump narrated his life's story at the southern edge of Chippewa Square in Savannah, Georgia, as he sat at a bus stop bench. There were other scenes filmed in and around the Savannah area as well, including a running shot on the Richard V. Woods Memorial Bridge in Beaufort while he was being interviewed by the press, and on West Bay Street in Savannah.[24] Most of the college campus scenes were filmed in Los Angeles at the University of Southern California. The lighthouse that Forrest runs across to reach the Atlantic Ocean the first time is the Marshall Point Lighthouse in Port Clyde, Maine. Additional scenes were filmed in Arizona, Utah's Monument Valley, and Montana's Glacier National Park.[25]

Visual effects

Ken Ralston and his team at Industrial Light & Magic were responsible for the film's visual effects. Using CGI techniques, it was possible to depict Gump meeting deceased personages and shaking their hands. Hanks was first shot against a blue screen along with reference markers so that he could line up with the archive footage.[26] To record the voices of the historical figures, voice actors were filmed and special effects were used to alter lip-syncing for the new dialogue.[15] Archival footage was used and with the help of such techniques as chroma key, image warping, morphing, and rotoscoping, Hanks was integrated into it.

In one Vietnam War scene, Gump carries Bubba away from an incoming napalm attack. To create the effect, stunt actors were initially used for compositing purposes. Then, Hanks and Williamson were filmed, with Williamson supported by a cable wire as Hanks ran with him. The explosion was then filmed, and the actors were digitally added to appear just in front of the explosions. The jet fighters and napalm canisters were also added by CGI.[27]

The CGI removal of actor Gary Sinise's legs, after his character had them amputated, was achieved by wrapping his legs with a blue fabric, which later facilitated the work of the "roto-paint" team to paint out his legs from every single frame. At one point, while hoisting himself into his wheelchair, his legs are used for support.[28]

The scene where Forrest spots Jenny at a peace rally at the Lincoln Memorial and Reflecting Pool in Washington, D.C., required visual effects to create the large crowd of people. Over two days of filming, approximately 1,500 extras were used.[29] At each successive take, the extras were rearranged and moved into a different quadrant away from the camera. With the help of computers, the extras were multiplied to create a crowd of several hundred thousand people.[7][29]

Release

Critical reception

The film received generally positive reviews from critics but acclaim from audiences. The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported that 72% of critics gave the film a positive review, with an average rating of 7.2/10, based on a sample of 88 reviews. The website's critical consensus states, "Forrest Gump may be an overly sentimental film with a somewhat problematic message, but its sweetness and charm are usually enough to approximate true depth and grace."[30] At the website Metacritic, the film earned a rating of 82 out of 100 based on 20 reviews by mainstream critics.[31] CinemaScore reported that audiences gave the film a rare "A+" grade.[32]

The story was commended by several critics. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times wrote, "I've never met anyone like Forrest Gump in a movie before, and for that matter I've never seen a movie quite like 'Forrest Gump.' Any attempt to describe him will risk making the movie seem more conventional than it is, but let me try. It's a comedy, I guess. Or maybe a drama. Or a dream. The screenplay by Eric Roth has the complexity of modern fiction...The performance is a breathtaking balancing act between comedy and sadness, in a story rich in big laughs and quiet truths...What a magical movie."[33] Todd McCarthy of Variety wrote that the film "has been very well worked out on all levels, and manages the difficult feat of being an intimate, even delicate tale played with an appealingly light touch against an epic backdrop."[34] The film did receive notable pans from several major reviewers. Anthony Lane of The New Yorker called the film "Warm, wise, and wearisome as hell."[35] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly said that the film "reduces the tumult of the last few decades to a virtual-reality theme park: a baby-boomer version of Disney's America."[36]

Critics have compared Gump with various characters and people including Huckleberry Finn, Bill Clinton, and Ronald Reagan.[37][38][39] Peter Chomo writes that Gump acts as a "social mediator and as an agent of redemption in divided times".[40] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone called Gump "everything we admire in the American character – honest, brave, and loyal with a heart of gold."[41] The New York Times reviewer Janet Maslin called Gump a "hollow man" who is "self-congratulatory in his blissful ignorance, warmly embraced as the embodiment of absolutely nothing."[42] Marc Vincenti of Palo Alto Weekly called the character "a pitiful stooge taking the pie of life in the face, thoughtfully licking his fingers."[43] Bruce Kawin and Gerald Mast's textbook on film history notes that Forrest Gump's dimness was a metaphor for glamorized nostalgia in that he represented a blank slate by which the Baby Boomer generation projected their memories of those events.[44]

The film is commonly seen as a polarizing one for audiences, with Entertainment Weekly writing in 2004, "Nearly a decade after it earned gazillions and swept the Oscars, Robert Zemeckis's ode to 20th-century America still represents one of cinema's most clearly drawn lines in the sand. One half of folks see it as an artificial piece of pop melodrama, while everyone else raves that it's sweet as a box of chocolates."[45]

Box office performance

Produced on a budget of $55 million, Forrest Gump opened in 1,595 theaters in its first weekend of domestic release, earning $24,450,602.[1] Motion picture business consultant and screenwriter Jeffrey Hilton suggested to producer Wendy Finerman to double the P&A (film marketing budget) based on his viewing of an early print of the film. The budget was immediately increased, per his advice. The film placed first in the weekend's box office, narrowly beating The Lion King, which was in its fourth week of release.[1] For the first ten weeks of its release, the film held the number one position at the box office.[46] The film remained in theaters for 42 weeks, earning $329.7 million in the United States and Canada, making it the fourth-highest-grossing film at that time (behind only E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Star Wars IV: A New Hope, and Jurassic Park).[46][47] Box Office Mojo estimates that the film sold over 78.5 million tickets in the US in its initial theatrical run.[48]

The film took 66 days to surpass $250 million and was the fastest grossing Paramount film to pass $100 million, $200 million, and $300 million in box office receipts (at the time of its release).[49][50][51] The film had gross receipts of $329,694,499 in the U.S. and Canada and $347,693,217 in international markets for a total of $677,387,716 worldwide.[1] Even with such revenue, the film was known as a "successful failure"—due to distributors' and exhibitors' high fees, Paramount's "losses" clocked in at $62 million, leaving executives realizing the necessity of better deals.[52] This has, however, also been associated with Hollywood accounting, where expenses are inflated in order to minimize profit sharing. It is Robert Zemeckis' highest-grossing film to date.

Home media

Forrest Gump was first released on VHS tape on April 27, 1995, as a two-disc Laserdisc set on April 28, 1995, before being released in a two-disc DVD set on August 28, 2001. Special features included director and producer commentaries, production featurettes, and screen tests.[53] The film was released on Blu-ray in November 2009.[54] Paramount released the film on Ultra HD Blu-ray in June 2018.[55]

Accolades

Forrest Gump won Best Picture, Best Actor in a Leading Role (Hanks won the previous year for Philadelphia), Best Director, Best Visual Effects, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Film Editing at the 67th Academy Awards. The film was nominated for seven Golden Globe Awards, winning three of them: Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama, Best Director – Motion Picture, and Best Motion Picture – Drama. The film was also nominated for six Saturn Awards and won two for Best Fantasy Film and Best Supporting Actor (Film).

In addition to the film's multiple awards and nominations, it has also been recognized by the American Film Institute on several of its lists. The film ranks 37th on 100 Years...100 Cheers, 71st on 100 Years...100 Movies, and 76th on 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition). In addition, the quote "Mama always said life was like a box of chocolates. You never know what you're gonna get," was ranked 40th on 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes.[56] The film also ranked at number 61 on Empire's list of the 100 Greatest Movies of All Time.[57]

In December 2011, Forrest Gump was selected for preservation in the Library of Congress' National Film Registry.[58] The Registry said that the film was "honored for its technological innovations (the digital insertion of Gump seamlessly into vintage archival footage), its resonance within the culture that has elevated Gump (and what he represents in terms of American innocence) to the status of folk hero, and its attempt to engage both playfully and seriously with contentious aspects of the era's traumatic history."[59]

American Film Institute Lists

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies – #71

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs – Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions – Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains:

- Forrest Gump – Nominated Hero

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- "Mama always said life was like a box of chocolates. You never know what you're gonna get." – #40

- "Mama says, 'Stupid is as stupid does.'" – Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores – Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – #37

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – #76

- AFI's 10 Top 10 – Nominated Epic Film

Author controversy

Winston Groom was paid $350,000 for the screenplay rights to his novel Forrest Gump and was contracted for a 3 percent share of the film's net profits.[60] However, Paramount and the film's producers did not pay him, using Hollywood accounting to posit that the blockbuster film lost money. Tom Hanks, by contrast, contracted for a percent share of the film's gross receipts instead of a salary, and he and director Zemeckis each received $40 million.[60][61] Additionally, Groom was not mentioned once in any of the film's six Oscar-winner speeches.[62]

Groom's dispute with Paramount was later effectively resolved after Groom declared he was satisfied with Paramount's explanation of their accounting, this coinciding with Groom receiving a seven-figure contract with Paramount for film rights to another of his books, Gump & Co.[63] This film was never made, remaining in development hell for at least a dozen years.[64]

Symbolism

Feather

—producer Wendy Finerman[39]

Various interpretations have been suggested for the feather present at the opening and conclusion of the film. Sarah Lyall of The New York Times noted several suggestions made about the feather: "Does the white feather symbolize the unbearable lightness of being? Forrest Gump's impaired intellect? The randomness of experience?"[65] Hanks interpreted the feather as: "Our destiny is only defined by how we deal with the chance elements to our life and that's kind of the embodiment of the feather as it comes in. Here is this thing that can land anywhere and that it lands at your feet. It has theological implications that are really huge."[66] Sally Field compared the feather to fate, saying: "It blows in the wind and just touches down here or there. Was it planned or was it just perchance?"[67] Visual effects supervisor Ken Ralston compared the feather to an abstract painting: "It can mean so many things to so many different people."[68]

Political interpretations

In Tom Hanks' words, "The film is non-political and thus non-judgmental."[39] Nevertheless, in 1994, CNN's Crossfire debated whether the film promoted conservative values or was an indictment of the counterculture movement of the 1960s. Thomas Byers, in a Modern Fiction Studies article, called the film "an aggressively conservative film".[69]

—producer Steve Tisch[69]

It has been noted that while Gump follows a very conservative lifestyle, Jenny's life is full of countercultural embrace, complete with drug usage, promiscuity, and antiwar rallies, and that their eventual marriage might be a kind of reconciliation.[33] Jennifer Hyland Wang argued in a Cinema Journal article that Jenny's death to an unnamed virus "...symbolizes the death of liberal America and the death of the protests that defined a decade [1960s]." She also notes the film's screenwriter, Eric Roth, when developing the screenplay from the novel, had "...transferred all of Gump's flaws and most of the excesses committed by Americans in the 1960s and 1970s to her [Jenny]."[40]

Other commentators believe the film forecast the 1994 Republican Revolution and used the image of Forrest Gump to promote movement leader Newt Gingrich's traditional, conservative values. Jennifer Hyland Wang observes that the film idealizes the 1950s, as made evident by the lack of "whites only" signs in Gump's Southern childhood, and "revisions" [sic] the 1960s as a period of social conflict and confusion. She argues that this sharp contrast between the decades criticizes the counterculture values and reaffirms conservatism.[70] As viewed by political scientist Joe Paskett,[35] this film is "one of the best films of all time".[71] Wang argued the film was used by Republican politicians to illustrate a "traditional version of recent history" to gear voters towards their ideology for the congressional elections.[40] In addition, presidential candidate Bob Dole cited the film's message in influencing his campaign with its "...message that has made [the film] one of Hollywood's all-time greatest box office hits: no matter how great the adversity, the American Dream is within everybody's reach."[40]

In 1995, National Review included Forrest Gump in its list of the "Best 100 Conservative Movies" of all time.[72] Then, in 2009, the magazine ranked the film number four on its 25 Best Conservative Movies of the Last 25 Years list.[73] "Tom Hanks plays the title character, an amiable dunce who is far too smart to embrace the lethal values of the 1960s. The love of his life, wonderfully played by Robin Wright Penn, chooses a different path; she becomes a drug-addled hippie, with disastrous results."[73]

James Burton, a communication arts professor at Salisbury University, argued that conservatives claimed Forrest Gump as their own due less to the content of the film and more to the historical and cultural context of 1994. Burton claimed the film's content and advertising campaign were affected by the cultural climate of the 1990s, which emphasized family values and "American values"—values epitomized in the successful book Hollywood vs. America. He claimed this climate influenced the apolitical nature of the film, which allowed for many different political interpretations.[74]

Burton points out that many conservative critics and magazines (John Simon, James Bowman, the World Report) initially either criticized the film or praised it only for its non-political elements. Only after the popularity of the film was well-established did conservatives embrace the film as an affirmation of traditional values. Burton implies the liberal-left could have prevented the conservatives from claiming rights to the film, had it chosen to vocalize elements of the film such as its criticism of military values. Instead, the liberal-left focused on what the film omitted, such as the feminist and civil rights movements.[74]

Some commentators see the conservative readings of Forrest Gump as indicants of the death of irony in American culture. Vivian Sobchack notes that the film's humor and irony rely on the assumption of the audience's historical (self-) consciousness.[74]

Soundtrack

The 32-song soundtrack from the film was released on July 6, 1994. With the exception of a lengthy suite from Alan Silvestri's score, all the songs are previously released; the soundtrack includes songs from Elvis Presley, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Aretha Franklin, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Three Dog Night, The Byrds, The Beach Boys, The Jimi Hendrix Experience, The Doors, The Mamas & the Papas, The Doobie Brothers, Simon & Garfunkel, Bob Seger, and Buffalo Springfield among others. Music producer Joel Sill reflected on compiling the soundtrack: "We wanted to have very recognizable material that would pinpoint time periods, yet we didn't want to interfere with what was happening cinematically."[75] The two-disc album has a variety of music from the 1950s–1980s performed by American artists. According to Sills, this was due to Zemeckis' request, "All the material in there is American. Bob (Zemeckis) felt strongly about it. He felt that Forrest wouldn't buy anything but American."[75]

The soundtrack reached a peak of number 2 on the Billboard album chart.[75] The soundtrack went on to sell twelve million copies, and is one of the top selling albums in the United States.[76] The score for the film was composed and conducted by Alan Silvestri and released on August 2, 1994.

Proposed sequel

The screenplay for the sequel was written by Eric Roth in 2001. It is based on the original novel's sequel, Gump and Co. written by Winston Groom in 1995. Roth's script begins with Forrest sitting on a bench waiting for his son to return from school. After the September 11 attacks, Roth, Zemeckis, and Hanks decided the story was no longer "relevant."[77] In March 2007, however, it was reported Paramount producers took another look at the screenplay.[64]

On the very first page of the sequel novel, Forrest Gump tells readers "Don't never let nobody make a movie of your life's story," though "Whether they get it right or wrong, it doesn't matter."[78] The first chapter of the book suggests the real-life events surrounding the film have been incorporated into Forrest's storyline, and that Forrest got a lot of media attention as a result of the film.[16] During the course of the sequel novel, Gump runs into Tom Hanks and at the end of the novel in the film's release, including Gump going on The David Letterman Show and attending the Academy Awards.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Forrest Gump (1994)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

- ↑ « News from the Library of Congress – 2011 National Film Registry More Than a Box of Chocolates »

- ↑ Smith, Neil (2017-06-16). "9 stars who turned down great film roles". BBC News. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

- ↑ "Iconic Roles and the Stars Who Regret Turning Them Down". Celebs.Answers.com. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ↑ Forbes staff (February 25, 2009). "Star Misses – 4) Forrest Gump Starring … John Travolta". Forbes. Archived from the original on July 22, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Wiser, Paige (December 17, 2006). "Might-have-beens who (thankfully) weren't: The wacky world of Hollywood's strangest casting calls" (Fee required). Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Mal, Vincent (July 6, 1994). "Show Some Gumption Hanks Excels in Tale of a Simple Man's Brushes with Fame" (Fee required). The Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

- ↑ Grimes, William (September 1, 1994). "Following the Star Of a Winsome Idiot". The New York Times. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- ↑ Daly, Sean (September 15, 1997). "Mykelti Williamson later said the 'Forrest Gump' role nearly ruined his acting career". Jet. FindArticles. Archived from the original on October 6, 2009. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- ↑ Boucher, Geoff (March 26, 2000). "On the Trail of a Hollywood Hyphenate; Rapper/Actor/Writer/Producer/Director. Is There Room For Anything Else on Ice Cube's Resume?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 21, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ↑ Wuntch, Philip (July 18, 1994). "In character – Sally Field finding the good roles" (Fee required). San Antonio Express-News. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- ↑ Daly, Sean (July 1, 2001). "Haley Joel Osment on Robots and Reality" (Fee required). The Buffalo News. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- ↑ Eler, Robert K. (January 22, 2009). "598-page encyclopedia covers a whole lot of Elvis". Arkansas Democrat Gazette. Archived from the original (Fee required) on July 21, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ↑ Forrest Gump-(Seeing is Believing: The Visual Effects of Forrest Gump-John Lennon with Dick Cavett) (DVD). Paramount Pictures. August 28, 2001.

- 1 2 Mills, Bart (July 8, 1994). "In 'Forrest Gump,' Historical Figures Speak for Themselves" (Fee required). Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Delarte, Alonso (February 2004). "Movies By The Book: Forrest Gump" (PDF). Bob's Poetry Magazine. p. 24. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2009. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- ↑ Plume, Kenneth (August 24, 2005). "Gilliam on Grimm". IGN. p. 3. Archived from the original on October 21, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ↑ Fretts, Bruce (November 3, 1995). "Get Barry". Entertainment Weekly. p. 2. Archived from the original on October 21, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ↑ McKenna, Kristine (December 19, 1993). "He's Serious About This One For Tom Hanks, it's been a long ride from 'Splash' to 'Philadelphia,' in which the likable comedy actor plays an AIDS patient who's fired from his job" (Fee required). Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ↑ Must-see sites abound along Blue Ridge Parkway – The Indiana Gazette Online: Indiana County Area News. Indianagazette.com (June 12, 2011). Retrieved on March 7, 2013.

- ↑ Film locations for Forrest Gump (1994). Movie-locations.com. Retrieved on March 7, 2013.

- ↑ Smith, Katherine. "Island getaway is motion-picture perfect". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on June 2, 2011.

- ↑ Grandfather Mountain audio tour

- 1 2 3 Forrest Gump-(Building the World of Gump: Production Design) (DVD). Paramount Pictures. August 28, 2001.

- ↑ D'Arc, James V. (2010). When Hollywood came to town: a history of moviemaking in Utah (1st ed.). Layton, Utah: Gibbs Smith. ISBN 9781423605874.

- ↑ Forrest Gump-(Through the eyes of Forrest Gump) (DVD). Paramount Pictures. August 28, 2001. Event occurs at 12:29.

- ↑ Forrest Gump-(Seeing is Believing: The Visual Effects of Forrest Gump-Vietnam) (DVD). Paramount Pictures. August 28, 2001.

- ↑ Forrest Gump-(Seeing is Believing: The Visual Effects of Forrest Gump-Lt. Dan's Legs) (DVD). Paramount Pictures. August 28, 2001.

- 1 2 Forrest Gump-(Seeing is Believing: The Visual Effects of Forrest Gump-Enhancing Reality) (DVD). Paramount Pictures. August 28, 2001.

- ↑ "Forrest Gump (1994)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ↑ "Forrest Gump Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ↑ Pamela McClintock (August 19, 2011). "Why CinemaScore Matters for Box Office". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- 1 2 Ebert, Roger (July 6, 1994). "Forrest Gump". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on June 20, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ↑ McCarthy, Todd (July 10, 1994). "Forrest Gump". Variety. Archived from the original on October 21, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- 1 2 Lane, Anthony. "Forrest Gump". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on October 21, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ↑ Gleiberman, Owen (July 15, 1994). "Forrest Gump (1994)". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 21, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ↑ Hinson, Hal (August 14, 1994). "Forrest Gump, Our National Folk Zero". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 21, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ↑ Rich, Frank (July 21, 1994). "The Gump From Hope". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 21, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Corliss, Richard; Julie Grace; Martha Smilgis (August 1, 1994). "The World According to Gump". Time. Archived from the original on October 21, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Wang, Jennifer Hyland (Spring 2000). ""A Struggle of Contending Stories": Race, Gender, and Political Memory in Forrest Gump" (PDF). Cinema Journal. 39 (3): 92–102. doi:10.1353/cj.2000.0009. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- ↑ Travers, Peter (December 8, 2000). "Forrest Gump". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 22, 2008. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- ↑ Burr, Ty (June 20, 1994). "Loss of innocence: 'Forrest Gump' at 10". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on October 21, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

Film critic Pauline Kael came out of retirement to bash the film on a book tour; by year's end, New York Times reviewer Janet Maslin had gone from mildly praising the film in her initial review to putting it on her worst of 1994 list, describing Forrest as a "hollow man" who's 'self-congratulatory in his blissful ignorance, warmly embraced as the embodiment of absolutely nothing.'

- ↑ Vincenti, Marc (August 1994). "Forrest Gump". Palo Alto Weekly. Archived from the original on June 16, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ↑ Mast, Gerald (2007). A Short History of the Movies: 10th Edition. London: Longman.

- ↑ Bal, Sumeet; Marc Bernardin; Monica Mehta; Joshua Rich; Erin Richter; Michael Sauter; Missy Schwartz; Nancy Sidewater (January 9, 2004). "Cry Hard 2 The Readers Strike Back". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 21, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- 1 2 "Forrest Gump Weekend Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

- ↑ "All Time Box Office Domestic Grosses". Box Office Mojo.

- ↑ "Forrest Gump (1994)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ↑ "Fastest to $100 million". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

- ↑ "Fastest to $200 million". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

- ↑ "Fastest to $300 million". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

- ↑ McDonald, Paul, and Janet Wasko. The Contemporary Hollywood Film Industry. Malden: Blackwell, 2008. Pg:79 #

- ↑ Lowman, Rob (August 28, 2001). "Video Enchanted Forrest the Much-beloved "Forrest Gump" Arrives on DVD with Sweetness Intact" (Fee required). Beacon Journal. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- ↑ Schweiger, Arlen (June 23, 2009). "Paramount Saves Top Titles for Blu-ray 'Sapphire' Treatment". Electronic House. Archived from the original on October 21, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ↑ "Paramount Preps 'Forrest Gump' for 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray | High-Def Digest". www.highdefdigest.com. Retrieved 2018-04-03.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years... The Complete Lists". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- ↑ Braund, Simon; et al. "Empire's 100 Greatest Movies Of All Time". Empire. Retrieved November 16, 2013.

- ↑ Nuckols, Ben (December 28, 2011). "Forrest Gump, Hannibal Lecter join film registry". Associated Press. Cox Newspapers. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- ↑ "2011 National Film Registry More Than a Box of Chocolates". Library of Congress. December 28, 2011. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- 1 2 Horn, John (May 25, 1995). "'Forrest Gump' Has Yet to Make a Net Profit". The Journal Record. FindArticles. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

- ↑ Davis, Charles E. (Summer 1997). "Accounting is like a box of chocolates: A lesson in cost behavior". Journal of Accounting Education. 15 (3): 307–318. doi:10.1016/S0748-5751(97)00008-0.

- ↑ Turan, Kenneth (March 28, 1995). "Calender Goes to the Oscars Analysis Life Is Like a Box of Oscars But Statues Are Divvied Up, Quite Fittingly" (Fee required). Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ↑ "'Gump' Author Settles Fight With Studio". San Francisco Chronicle (June 15, 1995). Retrieved on June 9, 2015.

- 1 2 Tyler, Josh (March 7, 2007). "Forrest Gump Gets A Sequel". Cinema Blend. Archived from the original on October 22, 2010. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

- ↑ Lyall, Sarah (July 31, 1994). "It's 'Forrest Gump' vs. Harrumph". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 22, 2010. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

- ↑ Forrest Gump-(Through the eyes of Forrest Gump) (DVD). Paramount Pictures. August 28, 2001. Event occurs at 23:27.

- ↑ Forrest Gump-(Through the eyes of Forrest Gump) (DVD). Paramount Pictures. August 28, 2001. Event occurs at 23:57.

- ↑ Forrest Gump-(Through the eyes of Forrest Gump) (DVD). Paramount Pictures. August 28, 2001. Event occurs at 26:29.

- 1 2 Byers, Thomas B. (1996). "History Re-Membered: Forrest Gump, Postfeminist Masculinity, and the Burial of the Counterculture". Modern Fiction Studies. 42 (2): 419–444. doi:10.1353/mfs.1995.0102. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- ↑ Wang, Jennifer (Spring 2000). ""A Struggle of Contending Stories": Race, Gender, and Political Memory in "Forrest Gump"". Cinema Journal. 39 (3): 92–115. doi:10.1353/cj.2000.0009.

- ↑ Gordinier, Jeff (February 10, 1995). "Mr. Gump Goes to Washington". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 22, 2010. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

- ↑ Quillen, Ed (May 7, 1995). "Why are modern conservatives so enchanted with Forrest Gump?". Denver Post.

- 1 2 Miller, John J. (February 23, 2009). "The Best Conservative Movies". National Review. Archived from the original on October 26, 2010. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Burton, James Amos (September 2007). "Film, History and Cultural Memory: Cinematic Representations of Vietnam-Era America During the Culture Wars, 1987–1995". PhD Thesis.

- 1 2 3 Rice, Lynette (August 14, 1994). "Songs Set the Mood for 'Gump'". Gainesville Sun. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- ↑ "Top Albums at the Recording Industry Association of America". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on June 19, 2004. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

- ↑ Sciretta, Peter (December 7, 2008). "9/11 Killed the Forrest Gump Sequel". /Film. Archived from the original on October 22, 2010. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

- ↑ Groom, Winston (1996). Gump & Co. Pocket Books. p. 1. ISBN 0-671-52264-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Forrest Gump. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Forrest Gump |