Midnight Cowboy

| Midnight Cowboy | |

|---|---|

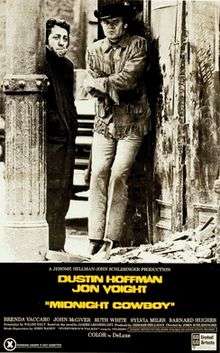

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Schlesinger |

| Produced by | Jerome Hellman |

| Screenplay by | Waldo Salt |

| Based on |

Midnight Cowboy by James Leo Herlihy |

| Starring | |

| Music by | John Barry |

| Cinematography | Adam Holender |

| Edited by | Hugh A. Robertson |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 113 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.2 million[1] |

| Box office | $44.8 million[2] |

Midnight Cowboy is a 1969 American buddy drama film. Based on the 1965 novel of the same name by James Leo Herlihy, the film was written by Waldo Salt, directed by John Schlesinger, and stars Jon Voight and Dustin Hoffman, with notable smaller roles being filled by Sylvia Miles, John McGiver, Brenda Vaccaro, Bob Balaban, Jennifer Salt, and Barnard Hughes. Set in New York City, Midnight Cowboy depicts the unlikely friendship between two hustlers: naive prostitute Joe Buck (Voight), and ailing con man "Ratso" Rizzo (Hoffman).

The film won three Academy Awards: Best Picture, Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay. Midnight Cowboy is the only X-rated film ever to win Best Picture (though such a classification no longer exists), and was the first gay-related Best Picture winner.[3][4] It has since been placed 36th on the American Film Institute's list of the 100 greatest American films of all time, and 43rd on its 2007 updated version.

In 1994, Midnight Cowboy was deemed "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant" by the Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry.[5]

Plot

Joe Buck, a young Texan working as a dishwasher, quits his job and heads to New York City to become a prostitute. Initially unsuccessful, he manages to bed a middle-aged New York woman in her posh apartment, but the encounter ends badly: he gives her money after she throws a tantrum when he requests payment, not realizing she is a call girl.

Joe meets Enrico Salvatore "Ratso" Rizzo, a con man with a limp who takes $20 from him by ostensibly introducing him to a pimp. After discovering that the man is actually an unhinged religious fanatic, Joe flees in pursuit of Ratso but cannot find him. Joe spends his days wandering the city and sitting in his hotel room. Soon broke, he is locked out of his hotel room and his belongings are impounded.

Joe tries to make money by receiving oral sex from a young man in a movie theater, but learns after-the-fact that the young man has no money. Joe threatens him and asks for his watch, but eventually lets him go unharmed. The next day, Joe spots Ratso and angrily shakes him down. Ratso offers to share the apartment in a condemned building where he is squatting. Joe reluctantly accepts his offer, and they begin a "business relationship" as hustlers. As they develop a bond, Ratso's health grows steadily worse.

In a flashback, Joe's grandmother raises him after his mother abandons him. He also has a tragic relationship with Annie, a mentally unstable girl. Ratso tells Joe his father was an illiterate Italian immigrant shoeshiner whose job led to a bad back and lung damage from long-term exposure to shoe polish. Ratso learned shoeshining from his father but considers it demeaning and generally refuses to do it (although he does shine Joe's cowboy boots to help him attract clients). Ratso harbors hopes of moving to Miami, shown in daydreams in which he and Joe frolic carefree on a beach and are surrounded by dozens of adoring women.

An eccentric man and woman approach Joe in a diner and give him a flyer inviting him to a Warhol-esque party; Joe and Ratso attend, but Ratso's poor health and hygiene attract unwanted attention from several guests. Joe mistakes a joint for a cigarette and starts to hallucinate after taking several long puffs. He leaves the party with Shirley, a socialite who agrees to pay him $20 for spending the night, but Joe cannot perform sexually. They play Scribbage together and the resulting wordplay leads Shirley to suggest that Joe may be gay; suddenly he is able to perform. The next morning, she sets up her friend as Joe's next client and it appears that his career is starting to thrive.

When Joe returns home, Ratso is bedridden and feverish. He refuses medical help and begs Joe to put him on a bus to Florida. Desperate, Joe picks up a man in an amusement arcade and robs him during a violent encounter in the man's hotel room. Joe buys bus tickets with the money so he and Ratso can board a bus to Florida. During the trip, Ratso's health deteriorates further: he becomes incontinent and sweat-drenched.

At a rest stop, Joe buys new clothing for Ratso and himself and discards his cowboy outfit. On the bus, Joe muses that there must be easier ways to earn a living than hustling, and tells Ratso he plans to get a regular job in Florida. When Ratso fails to respond, Joe realizes he is dead. The driver tells Joe there is nothing to do but continue to Miami and asks Joe to close Ratso's eyelids. Joe, with tears welling in his eyes, sits with his arm around his dead friend.

Cast

- Jon Voight as Joe Buck

- Dustin Hoffman as Enrico Salvatore "Ratso" Rizzo

- Sylvia Miles as Cass

- John McGiver as Mr. O'Daniel

- Brenda Vaccaro as Shirley

- Barnard Hughes as Towny

- Ruth White as Sally Buck

- Jennifer Salt as Annie

- Gilman Rankin as Woodsy Niles

- Georgann Johnson as Rich Lady

- Anthony Holland as TV Bishop

- Bob Balaban as Young Student

Production

The opening scenes were filmed in Big Spring, Texas. A roadside billboard, stating "IF YOU DON'T HAVE AN OIL WELL...GET ONE!" was shown as the New York-bound bus carrying Joe Buck rolled through Texas.[6] Such advertisements, common in the Southwestern United States in the late-1960s and through the 1970s, promoted Eddie Chiles's Western Company of North America.[7] In the film, Joe stays at the Hotel Claridge, at the southeast corner of Broadway and West 44th Street in Midtown Manhattan. His room overlooked the northern half of Times Square.[8] The building, designed by D. H. Burnham & Company and opened in 1911, was demolished in 1972.[9] A motif featured three times throughout the New York scenes was the sign at the top of the facade of the Mutual of New York (MONY) Building at 1740 Broadway.[6] It was extended into the Scribbage scene with Shirley the socialite, when Joe's incorrect spelling of the word "money" matched that of the signage.[10]

Despite his portrayal of Joe Buck, a character hopelessly out of his element in New York, Jon Voight is a native New Yorker, hailing from Yonkers.[11] Dustin Hoffman, who played a grizzled veteran of New York's streets, is from Los Angeles.[12][13] Voight was paid "scale", or the Screen Actors Guild minimum wage, for his portrayal of Joe Buck, a concession he willingly made to obtain the part.[14]

The line "I'm walkin' here!", which reached No. 27 on AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes, is often said to have been improvised, but producer Jerome Hellman disputes this account on the 2-disc DVD set of Midnight Cowboy. However, Hoffman explained it differently on an installment of Bravo's Inside the Actors Studio. He stated that there were many takes to hit the traffic light just right so that they wouldn't have to pause while walking. In that take, the timing was perfect, but a cab came out of nowhere and nearly hit them. Hoffman wanted to say, "We're filming a movie here!", but decided not to ruin the take.[15]

Upon initial review by the Motion Picture Association of America, Midnight Cowboy received a "Restricted" ("R") rating. However, after consulting with a psychologist, executives at United Artists were told to accept an "X" rating, due to the "homosexual frame of reference" and its "possible influence upon youngsters". The film was released with an X.[1] The MPAA later broadened the requirements for the "R" rating to allow more content and raised the age restriction from sixteen to seventeen. The film was later rated "R" for a reissue in 1971. The film retains its R rating.[1][16]

Reception

The film earned $11 million in rentals at the North American box office.[17]

Critical response to the film has been largely positive; Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune said of the film: "I cannot recall a more marvelous pair of acting performances in any one film."[18] In a 25th anniversary retrospective in 1994, Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly wrote: "Midnight Cowboy's peep-show vision of Manhattan lowlife may no longer be shocking, but what is shocking, in 1994, is to see a major studio film linger this lovingly on characters who have nothing to offer the audience but their own lost souls."[19]

Midnight Cowboy currently holds a 90% approval rating on online review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, with an average rating of 8.2/10, based on 62 reviews. The website's critical consensus states: "John Schlesinger's gritty, unrelentingly bleak look at the seedy underbelly of urban American life is undeniably disturbing, but Dustin Hoffman and Jon Voight's performances make it difficult to turn away."[20]

The film was one of President Jimmy Carter's favorites, with him reportedly screening it several times in the White House movie theater.[21]

Accolades

- Best Picture (Jerome Hellman) — Won

- Best Director (John Schlesinger) — Won

- Best Actor (Dustin Hoffman) — Nominated

- Best Actor (Jon Voight) — Nominated

- Best Supporting Actress (Sylvia Miles) — Nominated

- Best Adapted Screenplay (Waldo Salt) — Won

- Best Film Editing (Hugh A. Robertson) — Nominated

- Best Motion Picture — Drama (Jerome Hellman) — Nominated

- Best Director (John Schlesinger) — Nominated

- Best Actor — Motion Picture Drama (Dustin Hoffman) — Nominated

- Best Actor — Motion Picture Drama (Jon Voight) — Nominated

- Best Supporting Actress — Motion Picture Drama (Brenda Vaccaro) — Nominated

- New Star of the Year — Actor (Jon Voight) — Won

- Best Screenplay (Waldo Salt) — Nominated

- Best Film (Jerome Hellman) — Won

- Best Direction (John Schlesinger) — Won

- Best Actor in a Leading Role (Dustin Hoffman) — Won

- Most Promising Newcomer to Leading Film Roles (Jon Voight) — Won

- Best Screenplay (Waldo Salt) — Won

- Best Editing (Hugh A. Robertson) — Won

Berlin International Film Festival

- Golden Bear (John Schlesinger) — Nominated

- OCIC Award : A treatment of a contemporary social problem in a form at once artistic yet accessible to a vast public.

- Best Foreign Director (John Schlesinger) — Won

- Best Foreign Actor (Dustin Hoffman) — Won

- Top Ten Films — Won

- Best Actor (Jon Voight) — Won

- Best Actor (Dustin Hoffman) — 2nd place

- Best Supporting Actor (Dustin Hoffman) — 3rd place

Midnight Cowboy won the Directors Guild of America Award for Outstanding Directing – Feature Film and the Writers Guild of America Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

Soundtrack

John Barry, who supervised the music and composed the score, won a Grammy for Best Instrumental Theme.[22] Fred Neil's song "Everybody's Talkin'" won a Grammy Award for Best Male Pop Vocal Performance for Harry Nilsson. Schlesinger chose the song as its theme, and the song underscores the first act. Other songs considered for the theme included Nilsson's own "I Guess the Lord Must Be in New York City" and Randy Newman's "Cowboy". Bob Dylan wrote "Lay Lady Lay" to serve as the theme song, but did not finish it in time.[23] The movie's main theme, "Midnight Cowboy", featured harmonica by Toots Thielemans, but on its album version it was played by Tommy Reilly. The soundtrack album was released by United Artists Records in 1969.[24] The title music from Midnight Cowboy and some of the incidental ques were included in the documentary ToryBoy The Movie in 2011.

Theme song

- John Barry's version, used on the soundtrack, charted at #116 in 1969.

- Johnny Mathis's rendition, the only one containing lyrics, reached #20 on the U.S. Adult Contemporary chart in the fall of 1969.

- Ferrante & Teicher's version, by far the most successful, reached #10 on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 and #2 Adult Contemporary in the winter of 1970.

Certifications

| Region | Certification | Certified units/Sales |

|---|---|---|

| United States (RIAA)[25] | Gold | 500,000^ |

|

*sales figures based on certification alone | ||

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Balio, Tino (1987). United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 292. ISBN 9780299114404.

- ↑ "Midnight Cowboy". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 26, 2012.

- ↑ Mitchell, David (2014). "Gay Pasts and Disability Future(s) Tense". Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies. 8 (1): 1–16. doi:10.3828/jlcds.2014.1. Retrieved May 21, 2017.

- ↑ Ditmore, Melissa Hope (2006). "Midnight Cowboy". Encyclopedia of Prostitution and Sex Work. 1. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 307–308. ISBN 9780313329685.

- ↑ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". National Film Registry. The Library of Congress. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- 1 2 Chris (October 5, 2006). "Midnight Cowboy locations". Exquisitely Bored in Nacogdoches. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ↑ Popik, Barry (August 22, 2007). "The Big Apple: "If you don't have an oil well, get one!" (Eddie Chiles of Western Company)". The Big Apple. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Midnight Cowboy Film Locations". On the Set of New York. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Hotel Claridge, New York City". Skyscraper Page. Skyscraper Source Media. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Midnight Cowboy (1969)". AMC Filmsite. AMC Network Entertainment. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ↑ Votruba, Martin. "Jon Voight". Slovak Studies Program. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ↑ Smith, Grady (August 10, 2012). "Monitor: August 10, 2012". Entertainment Weekly. Time. p. 27. Missing or empty

|url=(help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ "The Birth of Dustin Hoffman". California Birth Records, 1905 Thru 1995. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ↑ Associated Press (August 29, 2013). "Voight Worked for Scale for 'Midnight Cowboy' Role". The Denver Post. Digital First Media. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ↑ Onda, David. "Greatest Unscripted Movie Moments". Xfinity. Archived from the original on August 17, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ Monaco, Paul (2001). History of the American Cinema: 1960–1969. The Sixties. 8. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 166. ISBN 9780520238046.

- ↑ "Big Rental Films of 1969". Variety. Penske Business Media. January 7, 1970. p. 15. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- ↑ Siskel, Gene (October 15, 1999). "The Movie Reviews". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- ↑ Gleiberman, Owen (March 4, 1994). "Midnight Cowboy". Entertainment Weekly. Time. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Midnight Cowboy (1969)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- ↑ Gottlieb, Meryl (September 10, 2016). "Here are 13 American President's Favorite Movies of All Time". Business Insider. Insider. Retrieved April 9, 2018.

- ↑ "Midnight Cowboy (1969)". IMDb. Retrieved March 14, 2014.

- ↑ Heylin, Clinton (1991). Dylan: Behind The Shades: The Biography. New York: Viking Books. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-6708-36024.

- ↑ "Midnight Cowboy — John Barry". Music Files. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ↑ "American album certifications – John Barry – Midnight Cowboy". Recording Industry Association of America. If necessary, click Advanced, then click Format, then select Album, then click SEARCH.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Midnight Cowboy |