From Here to Eternity

| From Here to Eternity | |

|---|---|

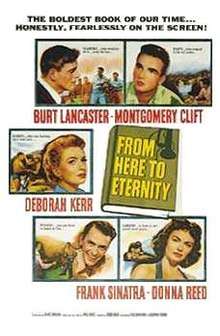

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Fred Zinnemann |

| Produced by | Buddy Adler |

| Screenplay by | Daniel Taradash |

| Based on |

From Here to Eternity by James Jones |

| Starring | |

| Music by | George Duning |

| Cinematography | Burnett Guffey |

| Edited by | William A. Lyon |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 118 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.7–2.5 million[1][2] |

| Box office | $30.5 million[1] |

From Here to Eternity is a 1953 drama film directed by Fred Zinnemann, and written by Daniel Taradash, based on the novel of the same name by James Jones. The picture deals with the tribulations of three U.S. Army soldiers, played by Burt Lancaster, Montgomery Clift, and Frank Sinatra, stationed on Hawaii in the months leading up to the attack on Pearl Harbor. Deborah Kerr and Donna Reed portray the women in their lives, and the supporting cast includes Ernest Borgnine, Philip Ober, Jack Warden, Mickey Shaughnessy, Claude Akins, and George Reeves.

The film won eight Academy Awards out of 13 nominations, including awards for Best Picture, Best Director (Fred Zinnemann), Adapted Screenplay, Supporting Actor (Frank Sinatra), and Supporting Actress (Donna Reed).[3] The film's title originally comes from a quote from Rudyard Kipling's 1892 poem "Gentlemen-Rankers", about soldiers of the British Empire who had "lost [their] way" and were "damned from here to eternity".

In 2002, From Here to Eternity was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Plot

In 1941, bugler and career soldier Private Robert E. Lee Prewitt (Montgomery Clift) transfers to a rifle company at Schofield Barracks on the island of Oahu. Captain Dana "Dynamite" Holmes (Philip Ober) has heard he is a talented middleweight boxer, and wants him to join his regimental team to secure a promotion for Holmes. Prewitt refuses, having stopped fighting because he blinded his sparring partner and close friend over a year before.

Holmes makes life as miserable as possible for Prewitt, hoping that he will change his mind, and then orders First Sergeant Milton Warden (Burt Lancaster) to prepare general court-martial papers, after Sergeant Galovitch (John Dennis) first insults Prewitt and then gives an unreasonable order that Prewitt refuses to obey. Warden suggests, however, that he try to get Prewitt to change his mind by doubling up on company punishment. The other non-commissioned officers join in the hazing, and Prewitt is supported only by his close friend, Private Angelo Maggio (Frank Sinatra).

Meanwhile, Warden, at the risk of a prison sentence, begins an affair with Holmes' neglected wife, Karen (Deborah Kerr). Sergeant Maylon Stark (George Reeves) has told Warden about Karen's many previous affairs at Fort Bliss, including with himself, though he adds "There's something mighty strange about that woman." As their relationship develops, Warden asks Karen about her affairs to test her sincerity, and Karen relates that Holmes has been unfaithful to her most of their marriage. She miscarried one night when Holmes returned home from seeing a hat-check girl, drunk and unable to call a doctor, rendering her barren. She then affirms her love for Warden, and tells him that if he became an officer, she could divorce Holmes and marry him; Warden reluctantly agrees to consider it.

Prewitt and Maggio spend their liberty at the New Congress Club, a gentlemen's club where Prewitt falls for Lorene (Donna Reed). She wants to marry a "proper" man with a "proper" job, and live a "proper" life. Maggio and Staff Sergeant James R. Judson (Ernest Borgnine) nearly come to blows at the club over Judson's loud piano playing. Later, Judson provokes Maggio by taking his photograph of his sister from him, kissing it, and whispering in Prewitt's ear. Maggio smashes a barstool over Judson's head. Judson pulls a switchblade, but then, Warden intervenes. Judson backs down, but warns Maggio that sooner or later, he will end up in the stockade, where Judson is in charge.

During a weekend liberty, while Prewitt is with Lorene at the New Congress Club, Maggio walks in drunk and in uniform having deserted his post. The military police arrest Maggio, and he is sentenced to six months in the stockade.

Sergeant Galovitch later picks a fight with Prewitt while he is on detail, and a crowd gathers as the two start fighting. At first, Prewitt resorts only to body blows, and even then pulling his punches, but his fighting spirit reemerges and he comes close to knocking Galovitch out before Holmes, who had been watching for some time from outside the crowd, finally steps in and stops the fight. Galovitch accuses Prewitt of starting the fight, but when the man in charge of the detail says that it was Galovitch, Holmes abruptly lets him off the hook and disperses the crowd.

The entire incident is witnessed by the base commander, who orders an investigation by the Inspector General. When the truth about Holmes is revealed to the commander he orders a court martial, but when Holmes begs for an alternative, an aide suggests that Holmes resign his commission; the commander accepts the suggestion and orders Holmes' resignation within the hour. Holmes' replacement, Captain Ross (John Bryant), reprimands the others involved in the hazing and orders the boxing team's framed photographs and trophies be destroyed; he then demotes Galovitch to private and puts him in charge of the latrine.

Maggio escapes from the stockade and, after telling of the abuse he suffered at Judson's hands, dies in Prewitt's arms. After tearfully playing Taps in tribute to his friend, Prewitt hunts Judson down and kills him with the same switchblade Judson pulled on Maggio earlier, but in so doing sustains a serious stomach wound, and so he goes into hiding at Lorene's house.

The military is caught completely by surprise on Sunday morning when the Japanese commence a pre-dawn attack on Pearl Harbor. Against Lorene's wishes, Prewitt attempts to rejoin his company under cover of darkness, but is shot dead by a patrol guarding against possible saboteurs. Warden sadly notes the irony of the boxing tournament being canceled because of the attack.

When Karen finds out that Warden never applied for officer training, she realizes they have no future together, and regretfully sails back to the mainland with her husband. On board the ship, Lorene and Karen meet, and Lorene says that her fiancé, named Prewitt, was a bomber pilot who was heroically killed during the attack. Karen recognizes Prewitt's name, but says nothing.

Cast

- Burt Lancaster as First Sergeant Milton Warden

- Montgomery Clift as Private Robert E. Lee "Prew" Prewitt

- Deborah Kerr as Karen Holmes

- Donna Reed as Alma Burke / Lorene

- Frank Sinatra as Private Angelo Maggio

- Philip Ober as Captain Dana "Dynamite" Holmes

- Mickey Shaughnessy as Sergeant Leva

- Harry Bellaver as Private First Class Mazzioli

- Ernest Borgnine as Staff Sergeant James R. "Fatso" Judson

- Jack Warden as Corporal Buckley

- John Dennis as Sergeant Ike Galovitch

- Merle Travis as Private Sal Anderson

- Tim Ryan as Sergeant Pete Karelsen

- Arthur Keegan as Treadwell

- Barbara Morrison as Mrs. Kipfer

- George Reeves as Sergeant Maylon Stark (uncredited)

- Claude Akins as Sergeant "Baldy" Dhom (uncredited)

- Alvin Sargent as Nair (uncredited)

- Robert J. Wilke as Sergeant Henderson (uncredited)

- Carleton Young as Colonel Ayres (uncredited)

- Kristine Miller as Georgette (uncredited)

Production

Hollywood legend has it that Frank Sinatra got the role in the film by means of his alleged Mafia connections, and it was the basis for a similar subplot in The Godfather.[4] However, that has been dismissed on several occasions by the cast and crew of the film. Director Fred Zinnemann commented that "the legend about a horse's head having been cut off is pure invention, a poetic license on the part of Mario Puzo, who wrote The Godfather".[4] One explanation of Sinatra's casting is that his then-wife Ava Gardner persuaded studio head Harry Cohn's wife to use her influence with him; this version is related by Kitty Kelley in her Sinatra biography.[4]

Joan Crawford and Gladys George were offered roles, but George lost her role when the director decided he wanted to cast the female roles against type, and Crawford's demands to be filmed by her own cameraman led the studio to take a chance on Deborah Kerr, also playing against type.

Kim Stanley heavily campigned for the role of Lorene.[5]

The on-screen chemistry between Lancaster and Kerr may have spilled off-screen; it was alleged that the stars became sexual partners during filming.[6]

Two songs are noteworthy: "Re-Enlistment Blues", and "From Here to Eternity",[7] by Robert Wells and Fred Karger.

Differences from the novel

Several of the novel's controversial plot points were changed or eliminated for the film to satisfy the Production Code Office and the U.S. Army.[8][9] Army cooperation was necessary in order to shoot on location at Schofield Barracks, use training aircraft, and obtain military footage of Pearl Harbor for use in the film, as well as for cost reasons.[10][11] According to screenwriter Daniel Taradash, both the Code Office and the Army were impressed by his script, which reduced the number of censorship problems.[12]

In the novel, Lorene was a prostitute at a brothel, but in the film, she is a hostess at a private social club.[8] Karen's hysterectomy in the novel was caused by the unfaithful Holmes transmitting gonorrhea to her, but in the film, her hysterectomy resulted from a miscarriage, thus avoiding the topic of venereal disease. The changes were made to meet Code Office standards.[9]

In the novel, several of the enlisted men fraternize with homosexuals, and one soldier commits suicide as a result, but homosexuality is not mentioned or directly explored in the film. Again, the change was made to satisfy the Code Office.[9][13] However, J. E. Smyth has written that the film's treatment of Judson's behavior towards Maggio "has all the indications of sexual abuse, and therefore reintroduces the fear of homosexuality in the 1930s military that the rest of the script had to repress for obvious reasons of censorship".[14]

In the novel, Captain Holmes ironically receives his desired promotion, and is transferred out of the company. In the film, Holmes is forced to resign from the Army under threat of court-martial for his ill-treatment of Prewitt. The Army insisted on this change, which the filmmakers reluctantly made.[8][11][15] Director Zinnemann later complained that the scene where Holmes is reprimanded was "the worst moment in the film, resembling a recruiting short",[11] and wrote, "It makes me sick every time I see it."[16]

In the novel, Judson's systematic abuse of Maggio and other prisoners, including Prewitt himself at one point, is portrayed in detail. However, in the film, Maggio's abuse happens offscreen, and is told only verbally to Prewitt, who remains free. The Army required that the abuse of Maggio not be shown, and that Judson's behavior towards Maggio be portrayed as "a sadistic anomaly, and not as the result of Army policy, as depicted in Jones' book".[11] The filmmakers agreed, seeing these changes as improvements.[11][16] Maggio, who survives and is discharged in the novel, dies in the film,[8] having been combined with two other prisoner characters from the novel (one of whom is killed by Judson in the novel) to add drama and make Maggio a stronger, more tragic figure.[17][18][19] The Army was further pacified by the filmmakers' inclusion of a line suggesting that Maggio's death was partially caused by his falling off a truck during a prison break, rather than solely by Judson's beatings.[20]

Reception

Opening to rave reviews, From Here to Eternity proved to be an instant hit with critics and public alike, the Southern California Motion Picture Council extolling: "A motion picture so great in its starkly realistic and appealing drama that mere words cannot justly describe it."

Variety agreed:

The James Jones bestseller, From Here to Eternity, has become an outstanding motion picture in this smash screen adaptation. It is an important film from any angle, presenting socko entertainment for big business. The cast names are exceptionally good, the exploitation and word-of-mouth values are topnotch, and the prospects in all playdates are very bright, whether special key bookings or general run.[21]

Of the actors, Variety went on to say,

Burt Lancaster, whose presence adds measurably to the marquee weight of the strong cast names, wallops the character of Top Sergeant Milton Warden, the professional soldier who wet-nurses a weak, pompous commanding officer and the GIs under him. It is a performance to which he gives depth of character as well as the muscles which had gained marquee importance for his name. Montgomery Clift, with a reputation for sensitive, three-dimensional performances, adds another to his growing list as the independent GI who refuses to join the company boxing team, taking instead the 'treatment' dished out at the C.O.'s instructions. Frank Sinatra scores a decided hit as Angelo Maggio, a violent, likeable Italo-American GI. While some may be amazed at this expression of the Sinatra talent versatility, it will come as no surprise to those who remember the few times he has had a chance to be something other than a crooner in films.[21]

The New York Post applauded Frank Sinatra, remarking, "He proves he is an actor by playing the luckless Maggio with a kind of doomed gaiety that is both real and immensely touching." Newsweek also stated that, "Frank Sinatra, a crooner long since turned actor, knew what he was doing when he plugged for the role of Maggio." John McCarten of The New Yorker concurred, writing that the film "reveals that Frank Sinatra, in the part of Mr. Clift's best friend who winds up in the stockade, is a first-rate actor."[22]

The cast agreed; Burt Lancaster commented in the book Sinatra: An American Legend that, "[Sinatra's] fervour, his bitterness had something to do with the character of Maggio, but also with what he had gone through the last number of years. A sense of defeat and the whole world crashing in on him... They all came out in that performance."[4]

With a gross of $30.5 million equating to earnings of $12.2 million, From Here to Eternity was not only one of the top-grossing films of 1953, but one of the ten highest-grossing films of the decade. Adjusted for inflation, its box office gross would exceed US$277 million in 2017 dollars.[1]

Despite the positive response of the critics and public, the Army was reportedly not pleased with its depiction in the finished film, and refused to let its name be used in the opening credits.[23] The Navy also banned the film from being shown to its servicemen, calling it "derogatory of a sister service" and a "discredit to the armed services".[24]

- American Film Institute recognition

Awards and nominations

William Holden, who won the Best Actor Oscar for Stalag 17, felt that Lancaster or Clift should have won. Sinatra would later comment that he thought his performance of heroin addict Frankie Machine in The Man with the Golden Arm was more deserving of an Oscar than his role as Maggio.

Television

An unsuccessful 30 minute television pilot starring Darren McGavin as 1st Sgt Warden, Roger Davis as Pvt Pruitt, and Tom Nardini as Pvt Di Maggio was made in 1966.[28]

In 1979, William Devane starred as 1st Sgt Warden in a miniseries that became a television series in 1980.

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 "Box Office Information for 'From Here to Eternity'." The Numbers. Retrieved: April 12, 2012.

- ↑ Webster, David Kenyon. "Film Fare: Hollywood producers concentrate on fewer, more lavish pictures, theatre owners complain, but studios' profits are the best in year's Genghis Khan and Ben Hur." The Wall Street Journal, July 13, 1954, p. 1.

- 1 2 "The 26th Academy Awards (1954) Nominees and Winners." Oscars.org. Retrieved: December 20, 2015..

- 1 2 3 4 Sinatra 1995, p. 106

- ↑ "From Here to Eternity (1953)." Archived 2011-09-29 at the Wayback Machine. moviesplanet.com. Retrieved: May 31, 2011.

- ↑ Buford 2000

- ↑ Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 22 – Smack Dab in the Middle on Route 66: A skinny dip in the easy listening mainstream. [Part 1]" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries. Track 2.

- 1 2 3 4 Hischak 2012, p. 75.

- 1 2 3 Suid, 2002, p. 148

- ↑ Smyth 2014, pp. 130–131.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nixon, Rob. "From Here to Eternity: The Essentials." Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved: December 20, 2015.

- ↑ Dick 1992, p. 50.

- ↑ Beidler 1998, p. 127.

- ↑ Smyth 2014, pp. 139–140.

- ↑ Smyth 2014, p. 136.

- 1 2 Eagan 2010, p. 472.

- ↑ Smyth p. 126, 2014, pp. 135–136.

- ↑ Dick 1992, p. 146.

- ↑ Dick 1992, p. 149.

- ↑ Suid 2002, pp. 145–146.

- 1 2 Brogdon, William. "Review:'From Here to Eternity'". Variety, July 29, 1953. Retrieved: January 14, 2010.

- ↑ McCarten, John (August 8, 1953). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker: 52.

- ↑ Smyth 2014, p. 148.

- ↑ Smyth 2014, p. 147.

- ↑ "From Here to Eternity". Golden Globes. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ↑ "From Here to Eternity." Festival de Cannes. Retrieved: January 25, 2009.

- ↑ "Film in 1954". BAFTA. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ↑ Goldberg, Lee Unsold Television Pilots: 1955-1989 Adventures in Television, 5 Jul. 2015

Bibliography

- Beidler, Philip D. The Good War's Greatest Hits: World War II and American Remembering. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8203-2001-3.

- Buford, Kate. Burt Lancaster: An American Life. New York: Knopf, 2000. ISBN 0-679-44603-6.

- Dick, Bernard F., ed. "Chapter 6: An Interview with Daniel Taradash: From Harvard to Hollywood". Columbia Pictures: Portrait of a Studio. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 1992. ISBN 978-0-8131-3019-4.

- Dolan, Edward F., Jr. Hollywood Goes to War. London: Bison Books, 1985. ISBN 0-86124-229-7.

- Eagan, Daniel. America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. New York City: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2010. ISBN 978-0826-41849-4.

- Evans, Alun. Brassey's Guide to War Films. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books, 2000. ISBN 1-57488-263-5.

- Hischak, Thomas S. American Literature on Stage and Screen: 525 Works and Their Adaptations. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2012. ISBN 978-0-7864-6842-3.

- Sinatra, Nancy. Frank Sinatra: An American Legend. Chappaqua, New York: Readers Digest Association, 1995. ISBN 0-7621-0134-2.

- Smyth, J.E. Fred Zinnemann and the Cinema of Resistance. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2014. ISBN 978-1-61703-964-5.

- Suid, Lawrence H. Guts & Glory: The Making of the American Military Image in Film. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2002. ISBN 0-8131-2225-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to From Here to Eternity (film). |