The Bridge on the River Kwai

| The Bridge on the River Kwai | |

|---|---|

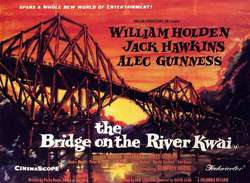

British theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | David Lean |

| Produced by | Sam Spiegel |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on |

The Bridge over the River Kwai by Pierre Boulle |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Malcolm Arnold |

| Cinematography | Jack Hildyard |

| Edited by | Peter Taylor |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 161 minutes |

| Country |

United Kingdom United States[1] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.8 million[2] |

| Box office | $30.6 million (initial release)[2] |

The Bridge on the River Kwai is a 1957 British-American epic war film directed by David Lean and based on the novel Le Pont de la Rivière Kwaï (1952) by Pierre Boulle. The film uses the historical setting of the construction of the Burma Railway in 1942–1943. The cast included William Holden, Jack Hawkins, Alec Guinness, and Sessue Hayakawa.

It was initially scripted by screenwriter Carl Foreman, who was later replaced by Michael Wilson. Both writers had to work in secret, as they were on the Hollywood blacklist and had fled to England in order to continue working. As a result, Boulle, who did not speak English, was credited and received the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay; many years later, Foreman and Wilson posthumously received the Academy Award.[3]

The film was widely praised, winning seven Academy Awards (including Best Picture) at the 30th Academy Awards. It used lush colour to bring out the British stiff upper lip of the colonel, played by Alec Guinness in an Oscar-winning performance.[4] In 1997, the film was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the United States Library of Congress. It has been included on the American Film Institute's list of best American films ever made.[5][6] In 1999, the British Film Institute voted The Bridge on the River Kwai the 11th greatest British film of the 20th Century.

Many historical inaccuracies in the film have often been noted by eyewitnesses to the building of the real Burma Railway and historians.[7][8][9][10]

Plot

In early 1943, British POWs arrive by train at a Japanese prison camp in Burma. The commandant, Colonel Saito, informs them that all prisoners, regardless of rank, are to work on the construction of a railway bridge over the River Kwai that will connect Bangkok and Rangoon. The senior British officer, Lieutenant Colonel Nicholson, informs Saito that the Geneva Conventions exempt officers from manual labour. Nicholson later forbids any escape attempts because they had been ordered by headquarters to surrender, and escapes could be seen as defiance of orders.

At the morning assembly, Nicholson orders his officers to remain behind when the enlisted men march off to work. Saito threatens to have them shot, but Nicholson refuses to back down. When Major Clipton, the British medical officer, warns Saito there are too many witnesses for him to get away with murder, Saito leaves the officers standing all day in the intense heat. That evening, the officers are placed in a punishment hut, while Nicholson is locked in an iron box.

Meanwhile, three prisoners attempt to escape. Two are shot dead, but United States Navy Commander Shears gets away, although badly wounded. He stumbles into a village of natives, who nurse him back to health and then help him leave by boat.

Meanwhile, the prisoners work as little as possible and sabotage whatever they can. Should Saito fail to meet his deadline, he would be obliged to commit ritual suicide. Desperate, he uses the anniversary of Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese War as an excuse to save face and announces a general amnesty, releasing Nicholson and his officers and exempting them from manual labour.

Nicholson is shocked by the poor job being done by his men. Over the protests of some of his officers, he orders Captain Reeves and Major Hughes to design and build a proper bridge to maintain his men's morale. As the Japanese engineers had chosen a poor site, the original construction is abandoned and a new bridge begun downstream.

Shears is enjoying his hospital stay in Ceylon when British Major Warden invites him to join a mission to destroy the bridge before it is completed. Shears is so appalled, he confesses he is not an officer; he impersonated one, expecting better treatment from the Japanese. Warden responds that he already knew and that the American Navy agreed to transfer him to the British to avoid embarrassment. Realising he has no choice, Shears volunteers.

Meanwhile, Nicholson drives his men hard to complete the bridge on time. For him, its completion will exemplify the ingenuity and hard work of the British Army long after the war's end. When he asks that their Japanese counterparts pitch in as well, a resigned Saito replies that he has already given the order. Clipton expresses grave doubts about the sanity of Colonel Nicholson's efforts to build the bridge in order to show up his Japanese captors.

The four commandos parachute in, though one is killed on landing. Later, Warden is wounded in an encounter with a Japanese patrol and has to be carried on a litter. He, Shears, and Canadian Lieutenant Joyce reach the river in time with the assistance of Siamese women bearers and their village chief, Khun Yai. Under cover of darkness, Shears and Joyce plant explosives on the bridge towers below the water line.

A train carrying important dignitaries and soldiers is scheduled to be the first to cross the bridge the following day, so Warden waits to destroy both. However, by daybreak the water level has dropped, exposing the wire connecting the explosives to the detonator. Nicholson spots the wire and brings it to Saito's attention. As the train approaches, they hurry down to the riverbank to investigate.

Joyce, manning the detonator, breaks cover and stabs Saito to death. Nicholson yells for help, while attempting to stop Joyce from reaching the detonator. When Joyce is mortally wounded by Japanese fire, Shears swims across the river, but is himself shot. Recognising the dying Shears, Nicholson exclaims, "What have I done?" Warden fires a mortar, wounding Nicholson. The dying colonel stumbles towards the detonator and collapses on the plunger just in time to blow up the bridge and send the train hurtling into the river below. Warden turns toward the only survivors of the commando raid, the women bearers, and begs their forgiveness for having to kill Joyce and Shears, and throws the mortar launcher away in disgust, and prepares to leave. Clipton, observing the carnage, shakes his head muttering, "Madness!, Madness!".

Cast

- William Holden as Commander Shears

- Alec Guinness as Lieutenant Colonel Nicholson

- Jack Hawkins as Major Warden

- Sessue Hayakawa as Colonel Saito

- James Donald as Major Clipton

- Geoffrey Horne as Lieutenant Joyce

- André Morell as Colonel Green

- Peter Williams as Captain Reeves

- John Boxer as Major Hughes

- Percy Herbert as Private Grogan

- Harold Goodwin as Private Baker

- Ann Sears as Nurse

- Henry Okawa as Captain Kanematsu

- K. Katsumoto as Lieutenant Miura

- M.R.B. Chakrabandhu as Yai

Production

Screenplay

The screenwriters, Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, were on the Hollywood blacklist and, even though living in exile in England, could only work on the film in secret. The two did not collaborate on the script; Wilson took over after Lean was dissatisfied with Foreman's work. The official credit was given to Pierre Boulle (who did not speak English), and the resulting Oscar for Best Screenplay (Adaptation) was awarded to him. Only in 1984 did the Academy rectify the situation by retroactively awarding the Oscar to Foreman and Wilson, posthumously in both cases. Subsequent releases of the film finally gave them proper screen credit. David Lean himself also claimed that producer Sam Spiegel cheated him out of his rightful part in the credits since he had had a major hand in the script.[11]

The film was relatively faithful to the novel, with two major exceptions. Shears, who is a British commando officer like Warden in the novel, became an American sailor who escapes from the POW camp. Also, in the novel, the bridge is not destroyed: the train plummets into the river from a secondary charge placed by Warden, but Nicholson (never realising "what have I done?") does not fall onto the plunger, and the bridge suffers only minor damage. Boulle nonetheless enjoyed the film version though he disagreed with its climax.[12]

Filming

Many directors were considered for the project, among them John Ford, William Wyler, Howard Hawks, Fred Zinnemann, and Orson Welles (who was also offered a starring role).[13][14]

The film was an international co-production between companies in Britain and the United States.[15]

Director David Lean clashed with his cast members on multiple occasions, particularly Alec Guinness and James Donald, who thought the novel was anti-British. Lean had a lengthy row with Guinness over how to play the role of Nicholson; Guinness wanted to play the part with a sense of humour and sympathy, while Lean thought Nicholson should be "a bore." On another occasion, they argued over the scene where Nicholson reflects on his career in the army. Lean filmed the scene from behind Guinness and exploded in anger when Guinness asked him why he was doing this. After Guinness was done with the scene, Lean said, "Now you can all fuck off and go home, you English actors. Thank God that I'm starting work tomorrow with an American actor (William Holden)."[16]

The film was made in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). The bridge in the film was near Kitulgala.

Guinness later said that he subconsciously based his walk while emerging from "the Oven" on that of his eleven-year-old son Matthew,[17] who was recovering from polio at the time, a disease that left him temporarily paralyzed from the waist down.[18] Guinness later reflected on the scene, calling it the "finest piece of work" he had ever done.[19]

Lean nearly drowned when he was swept away by the river current during a break from filming.[20]

The filming of the bridge explosion was to be done on 10 March 1957, in the presence of S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, then Prime Minister of Ceylon, and a team of government dignitaries. However, cameraman Freddy Ford was unable to get out of the way of the explosion in time, and Lean had to stop filming. The train crashed into a generator on the other side of the bridge and was wrecked. It was repaired in time to be blown up the next morning, with Bandaranaike and his entourage present.[20]

The producers nearly suffered a catastrophe following the filming of the bridge explosion. To ensure they captured the one-time event, multiple cameras from several angles were used. Ordinarily, the film would have been taken by boat to London, but due to the Suez crisis this was impossible; therefore the film was taken by air freight. When the shipment failed to arrive in London, a worldwide search was undertaken. To the producers' horror, the film containers were found a week later on an airport tarmac in Cairo, sitting in the hot sun. Although it was not exposed to sunlight, the heat-sensitive colour film stock should have been hopelessly ruined; however, when processed the shots were perfect and appeared in the film.[21]

Music and soundtrack

| The Bridge on the River Kwai (Original Soundtrack Recording) | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Various | |

| Released | 1957 |

| Recorded | October 21, 1957 |

| Genre | Soundtrack |

| Length | 44:49 |

| Label | Columbia |

| Producer | Various |

| Professional ratings | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Discogs | |

British composer Malcolm Arnold recalled that he had "ten days to write around forty-five minutes worth of music" - much less time than he was used to. He described the music for The Bridge on the River Kwai as the "worst job I ever had in my life" from the point of view of time.[24]

A memorable feature of the film is the tune that is whistled by the POWs—the first strain of the march "Colonel Bogey"—when they enter the camp.[25] Gavin Young[26] recounts meeting Donald Wise, a former prisoner of the Japanese who had worked on the Burma Railway. Young: "Donald, did anyone whistle Colonel Bogey ... as they did in the film?" Wise: "I never heard it in Thailand. We hadn't much breath left for whistling. But in Bangkok I was told that David Lean, the film's director, became mad at the extras who played the prisoners—us—because they couldn't march in time. Lean shouted at them, 'For God's sake, whistle a march to keep time to.' And a bloke called George Siegatz ... —an expert whistler—began to whistle Colonel Bogey, and a hit was born."

The march was written in 1914 by Kenneth J. Alford, a pseudonym of British Bandmaster Frederick J. Ricketts. The Colonel Bogey strain was accompanied by a counter-melody using the same chord progressions, then continued with film composer Malcolm Arnold's own composition, "The River Kwai March," played by the off-screen orchestra taking over from the whistlers, though Arnold's march was not heard in completion on the soundtrack. Mitch Miller had a hit with a recording of both marches.

In many tense, dramatic scenes, only the sounds of nature are used. An example of this is when commandos Warden and Joyce hunt a fleeing Japanese soldier through the jungle, desperate to prevent him from alerting other troops. Arnold won an Academy Award for the film's score.

| The Bridge on the River Kwai (Original Soundtrack Recording) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Performer(s) | Length |

| 1. | "Overture" (feat. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra) | Malcolm Arnold | 4:24 |

| 2. | "Colonel Bogey March" (feat. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra) | Malcolm Arnold | 2:52 |

| 3. | "Shear's Escape" (feat. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra) | Malcolm Arnold | 3:58 |

| 4. | "Nicholson's Victory" (feat. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra) | Malcolm Arnold | 4:45 |

| 5. | "Sunset" (feat. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra) | Malcolm Arnold | 3:54 |

| 6. | "Working on the Bridge" (feat. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra) | Malcolm Arnold | 2:58 |

| 7. | "Trek to the Bridge" (feat. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra) | Malcolm Arnold | 8:28 |

| 8. | "Camp Concert Dance" (feat. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra) | Malcolm Arnold | 2:36 |

| 9. | "Finale" (feat. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra) | Malcolm Arnold | 2:12 |

| 10. | "River Kwai March" (feat. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra) | Malcolm Arnold | 2:58 |

| 11. | "I Give My Heart (To No One But You)" (feat. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra) | Malcolm Arnold | 3:16 |

| 12. | "Dance Music" | Malcolm Arnold | 4:54 |

| 13. | "The River Kwai March/Colonel Bogey March" (feat. Mitch Miller & his orchestra) | Malcolm Arnold | 2:28 |

Historical accuracy

The plot and characters of Boulle's novel and the screenplay were almost entirely fictional.[27]

The conditions to which POW and civilian labourers were subjected were far worse than the film depicted.[28] According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission:

The notorious Burma-Siam railway, built by Commonwealth, Dutch and American prisoners of war, was a Japanese project driven by the need for improved communications to support the large Japanese army in Burma. During its construction, approximately 13,000 prisoners of war died and were buried along the railway. An estimated 80,000 to 100,000 civilians also died in the course of the project, chiefly forced labour brought from Malaya and the Dutch East Indies, or conscripted in Siam (Thailand) and Burma. Two labour forces, one based in Siam and the other in Burma, worked from opposite ends of the line towards the centre.[29]

Lieutenant Colonel Philip Toosey of the British Army was the real senior Allied officer at the bridge in question. Toosey was very different from Nicholson and was certainly not a collaborator who felt obliged to work with the Japanese. Toosey in fact did as much as possible to delay the building of the bridge. While Nicholson disapproves of acts of sabotage and other deliberate attempts to delay progress, Toosey encouraged this: termites were collected in large numbers to eat the wooden structures, and the concrete was badly mixed.[8][9] Some consider the film to be an insulting parody of Toosey.[8] On a BBC Timewatch programme, a former prisoner at the camp states that it is unlikely that a man like the fictional Nicholson could have risen to the rank of lieutenant colonel, and, if he had, due to his collaboration he would have been "quietly eliminated" by the other prisoners. Julie Summers, in her book The Colonel of Tamarkan, writes that Boulle, who had been a prisoner of war in Thailand, created the fictional Nicholson character as an amalgam of his memories of collaborating French officers.[8] He strongly denied the claim that the book was anti-British, although many involved in the film itself (including Alec Guinness) felt otherwise.[30] Ernest Gordon, a survivor of the railway construction and POW camps described in the novel/film, stated in a 1962 book, Through the Valley of the Kwai: "In Pierre Boulle's book The Bridge over the River Kwai and the film which was based on it, the impression was given that British officers not only took part in building the bridge willingly, but finished in record time to demonstrate to the enemy their superior efficiency. This was an entertaining story. But I am writing a factual account, and in justice to these men—living and dead—who worked on that bridge, I must make it clear that we never did so willingly. We worked at bayonet point and under bamboo lash, taking any risk to sabotage the operation whenever the opportunity arose."[7]

A 1969 BBC-TV documentary, Return to the River Kwai, made by former POW John Coast,[10] sought to highlight the real history behind the film (partly through getting ex-POWs to question its factual basis, for example Dr Hugh de Wardener and Lt-Col Alfred Knights), which angered many former POWs. The documentary itself was described by one newspaper reviewer when it was shown on Boxing Day 1974 (The Bridge on the River Kwai had been shown on BBC1 on Christmas Day 1974) as "Following the movie, this is a rerun of the antidote."[31]

Some of the characters in the film use the names of real people who were involved in the Burma Railway. Their roles and characters, however, are fictionalised. For example, a Sergeant-Major Risaburo Saito was in real life second in command at the camp. In the film, a Colonel Saito is camp commandant. In reality, Risaburo Saito was respected by his prisoners for being comparatively merciful and fair towards them. Toosey later defended him in his war crimes trial after the war, and the two became friends.

The major railway bridge described in the novel and film didn't actually cross the river known at the time as the Kwai. However, in 1943 a railway bridge was built by Allied POWs over the Mae Klong river – renamed as a result of the film Khwae Yai in the 1960s – at Tha Ma Kham, five kilometres from Kanchanaburi, Thailand.[32] Boulle had never been to the bridge. He knew that the railway ran parallel to the Kwae for many miles, and he therefore assumed that it was the Kwae which it crossed just north of Kanchanaburi. This was an incorrect assumption. The destruction of the bridge as depicted in the film is also entirely fictional. In fact, two bridges were built: a temporary wooden bridge and a permanent steel/concrete bridge a few months later. Both bridges were used for two years, until they were destroyed by Allied bombing. The steel bridge was repaired and is still in use today.[32]

- Japanese views of the novel & film

Japanese viewers disliked the film's "glorification" of a fictitious and indemonstrable "superiority of Western civilization". In particular, they resented the implication in the film that Japanese military engineers were less capable than their British counterparts. [33] [34] In fact, Japanese engineers had been surveying the route of the railway since 1937 and were highly organized.

The film contains a scene where Colonel Nicholson, while inspecting the bridge construction progress, refers to the Japanese overseeing them as "barbarians".[35] In the version of the movie releases on DVD in 2000, the reference is overdubbed with a water splash sound.

Reception

Box office performance

Variety reported that this film was the No. 1 moneymaker of 1958, with a US take of $18,000,000.[36] The second highest moneymaker of 1958 was Peyton Place at $12,000,000; in third place was Sayonara at $10,500,000.[36]

The film was re-released in 1964 and earned an estimated $2.6 million in North American rentals.[37]

Critical response

The film initially received generally positive reviews, with Guinness being widely praised for his performance. On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film received an approval rating of 94% based on 53 reviews, with an average rating of 9.3/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "This complex war epic asks hard questions, resists easy answers, and boasts career-defining work from star Alec Guinness and director David Lean."[38] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 87 out of 100 based on 14 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[39]

Roger Ebert gives the film four out of five stars.[40] The critic notes that the film is one of the few war movies that "focuses not on larger rights and wrongs but on individuals", but commented that the viewer is not certain what is intended by the final dialogue due to the film's shifting points of view.[41] Slant Magazine also gave the film four out of five stars.[42] Slant stated that "the 1957 epic subtly develops its themes about the irrationality of honor and the hypocrisy of Britain’s class system without ever compromising its thrilling war narrative", and in comparing to other films of the time said that Bridge on the River Kwai "carefully builds its psychological tension until it erupts in a blinding flash of sulfur and flame.".[43]

Variety gave high praise for the movie saying that it is "a gripping drama, expertly put together and handled with skill in all departments.".[44] Significant praise was also given to the actors especially Alec Guinness, Variety said that "the film is unquestionably Guinness’".[45] William Holden was also credited for his acting, he was said to give a solid characterization and was "easy, credible and always likeable in a role that is the pivot point of the story".[46]

Accolades

- American Film Institute

- 1998 — AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies — #13

- 2001 — AFI's 100 Years... 100 Thrills — #58

- 2006 — AFI's 100 Years... 100 Cheers — #14

- 2007 — AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) — #36

The film has been selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry.

The British Film Institute placed The Bridge on the River Kwai as the 11th greatest British film.

First TV broadcast

The 167-minute film was first telecast, uncut, by ABC-TV in color on the evening of 25 September 1966, as a three hours-plus ABC Movie Special. The telecast of the film lasted more than three hours because of the commercial breaks. It was still highly unusual at that time for a television network to show such a long film in one evening; most films of that length were still generally split into two parts and shown over two evenings. But the unusual move paid off for ABC—the telecast drew huge ratings.[47] On the evenings of 28 and 29 January 1973, ABC broadcast another David Lean colour spectacular, Lawrence of Arabia, but that broadcast was split into two parts over two evenings, due to the film's nearly four-hour length.[48]

Restorations

The film was restored in 1992 by Columbia Pictures. The separate dialogue, music and effects were located and remixed with newly recorded "atmospheric" sound effects.[49] The image was restored by OCS, Freeze Frame, and Pixel Magic with George Hively editing.[50]

On 2 November 2010 Columbia Pictures released a newly restored The Bridge on the River Kwai for the first time on Blu-ray. According to Columbia Pictures, they followed an all-new 4K digital restoration from the original negative with newly restored 5.1 audio.[51] The original negative for the feature was scanned at 4k (roughly four times the resolution in High Definition), and the colour correction and digital restoration were also completed at 4k. The negative itself manifested many of the kinds of issues one would expect from a film of this vintage: torn frames, embedded emulsion dirt, scratches through every reel, colour fading. Unique to this film, in some ways, were other issues related to poorly made optical dissolves, the original camera lens and a malfunctioning camera. These problems resulted in a number of anomalies that were very difficult to correct, like a ghosting effect in many scenes that resembles colour mis-registration, and a tick-like effect with the image jumping or jerking side-to-side. These issues, running throughout the film, were addressed to a lesser extent on various previous DVD releases of the film and might not have been so obvious in standard definition.[52]

In popular culture

- Balu Mahendra, the Tamil film director, saw the shooting of this film at Kitulgala, Sri Lanka during his school trip and was inspired to become a film director.[53]

- In 1962, Spike Milligan and Peter Sellers, with Peter Cook and Jonathan Miller, released the LP record Bridge On the River Wye (Parlophone LP PMC 1190, PCS 3036 (November 1962)). This spoof of the film was based on the script for the 1957 Goon Show episode "An African Incident". Shortly before its release, for legal reasons, producer George Martin edited out the 'K' every time the word 'Kwai' was spoken.[54]

- The comedy team of Wayne and Shuster performed a sketch titled "Kwai Me a River" on their 27 March 1967 TV show, in which an officer in the British Dental Corps is captured by the Japanese and, despite being comically unintimidated by any abuse the commander of the POW camp inflicts on him, is forced to build a (dental) "bridge on the river Kwai" for the commander and plans to include an explosive in the appliance to detonate in his mouth.[55]

See also

References

- ↑ "The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)". British Film Institute. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- 1 2 Sheldon Hall, Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History Wayne State University Press, 2010 p 161

- ↑ Aljean Harmetz (March 16, 1985). "Oscars Go to Writers of 'Kwai'". The New York Times.

- ↑ Wigley, Samuel. "10 great prisoner-of-war films". British Film Institute. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ On the AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies lists, in 1998 (#13) and 2007 (#36)

- ↑ Roger Ebert. "Great Movies: The First 100". Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- 1 2 Gordon, Ernest (1962). Through the Valley of the Kwai. New York: Harper & Row Publishers.

- 1 2 3 4 Summer, Julie (2005). The Colonel of Tamarkan. Simon & Schuster Ltd. ISBN 0-7432-6350-2.

- 1 2 Davies, Peter N. (1991). The Man Behind the Bridge. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-485-11402-X.

- 1 2 A transcript of the interview and the documentary as a whole can be found in the new edition of John Coast's book Railroad of Death.Coast, John (2014). Railroad of Death. Myrmidon. ISBN 978-1-905802-93-7.

- ↑ The Guardian, April 17, 1991

- ↑ Joyaux, Georges. The Bridge over the River Kwai: From the Novel to the Movie, Literature/Film Quarterly, published in the Spring of 1974. Retrieved 09-24-2015.

- ↑ Baer, William. "Film: The Bridge on the River Kwai", Crisis Magazine, published 09-01-2007. Retrieved 09-24-2015.

- ↑ "Flashback: A look back at this day in film history (The Bridge on the River Kwai released)" Archived 2015-09-25 at the Wayback Machine., www.focusfeatures.com, published 09-23-2015. Retrieved 09-24-2015.

- ↑ Monaco, Paul (2010). A History of American Movies: A Film-by-film Look at the Art, Craft, and Business of Cinema. Scarecrow Press. p. 349.

- ↑ (Piers Paul Read, Alec Guinness, 293)

- ↑ Jason, Gary. "Classic Problem, Classic Films", www.libertyunbound.com, published 09-19-2011. Retrieved 09-24-2015.

- ↑ Reichardt, Rita. "How Father Brown Led Sir Alec Guinness to the Church", www.catholicculture.org, published May/June, 2005. Retrieved 09-24-2015.

- ↑ Tollestrup, Jon. "The Bridge on the River Kwai - 1957", www.oscarwinningfilms.blogspot.co.uk, published 12-08-2013. Retrieved 09-24-2015.

- 1 2 "The Bridge on the River Kwai(disasters on the film set)", Purbeck Film Festival, published 08-24-2014. Retrieved 09-24-2015.

- ↑ Goldstein, Carly. "The Bridge on the River Kwai review", www.fromthecouchblog.wordpress.com, published 09-10-2013. Retrieved 09-24-2015.

- ↑ "The Bridge on the River Kwai soundtrack rating", www.allmusic.com. Retrieved 09-24-2015.

- ↑ "Malcolm Arnold's The Bridge on the River Kwai soundtrack", www.discogs.com. Retrieved 09-24-2015.

- ↑ Schafer, Murray. British Composers in Interview. XIII Malcolm Arnold. Faber and Faber, London, 1963, p150.

- ↑ The Colonel Bogey March MIDI file

- ↑ In his 1981 book Slow Boats to China, chapter 39, ISBN 978-0571251032

- ↑ "Remembering the railway: The Bridge on the River Kwai, www.hellfire-pass.commemoration.gov.au. Retrieved 09-24-2015.

- ↑ "links for research, Allied POWs under the Japanese". mansell.com. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ↑ Reading Room Manchester. "CWGC - Cemetery Details". cwgc.org. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ↑ Brownlow, Kevin (1996). David Lean: A Biography. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-14578-0. pp. 391 and 766n

- ↑ "Boxing Day [TV Listing]". The Guardian. London. 24 December 1974. p. 14.

- 1 2 "The Colonel of Tamarkan: Philip Toosey and the Bridge on the River Kwai", published by the National Army Museum on 03-04-2012. Retrieved 09-24-2015.

- ↑ Hirakawa Sukchiro, "Bridge on the River Kwai" http://www.fepow-community.org.uk/monthly_Revue/html/bridge_on_the_river_kwai.htm, accessed 6 Jan 2015

- ↑ Summers, Julie (2012), "The Colonel of Tamarkan: Philip Toosey and the Bridge on the River Kwai, p. 6 http://www.nam.ac.uk/whats-on/lunchtime-lectures/video-archive/colonel-tamarkan-philip-toosey-bridge-on-river-kwai, accessed 6 Jan 2015

- ↑ http://www.script-o-rama.com/movie_scripts/b/bridge-on-the-river-kwai-script.html

- 1 2 Steinberg, Cobbett (1980). Film Facts. New York: Facts on File, Inc. p. 23. ISBN 0-87196-313-2. When a film is released late in a calendar year (October to December), its income is reported in the following year's compendium, unless the film made a particularly fast impact. Figures are domestic earnings (United States and Canada) as reported each year in Variety (p. 17).

- ↑ "Big Rental Pictures of 1964", Variety, 6 January 1965 p 39. This figure is rentals accruing to distributors, not total gross.

- ↑ "The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ "The Bridge on the River Kwai Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ Roger Ebert (April 18, 1999) THE BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ↑ Roger Ebert (April 18, 1999) THE BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ↑ Blauvelt, Christian (September 20, 2010) The Bridge on the River Kwai. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ↑ Blauvelt, Christian (September 20, 2010) The Bridge on the River Kwai. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ↑ Kaplan, Mike (November 19, 1967) The Bridge on the River Kwai. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ↑ Kaplan, Mike (November 19, 1967) The Bridge on the River Kwai. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ↑ Kaplan, Mike (November 19, 1967) The Bridge on the River Kwai. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ↑ Gowran, Clay (11 October 1966) Nielsen Ratings Are Dim on New Shows, Chicago Tribune (noting film received a 38.3 rating to lead the national Nielsen ratings)

- ↑ "Nielsen Top Ten, January 29th – February 4th, 1973 | Television Obscurities". Tvobscurities.com. Retrieved 2014-05-16.

- ↑ "The Bridge on the River Kwai". DavidLean.com. Archived from the original on 2009-01-29.

- ↑ "The Bridge on the River Kwai Credits". BFI Film and TV Database.

- ↑ "Movies | Disc & Digital | Sony Pictures". Bridgeontheriverkwaibd.com. Retrieved 2014-05-16.

- ↑ Archived August 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ N. Venkateswaran (14 February 2014). "Balu Mahendra, who made his visuals speak, dies at 74". The Times of India. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ↑ "The Goon Show Site - Facts and Trivia". Thegoonshow.net. Retrieved 2014-05-16.

- ↑ "Wayne and Shuster Show, The Episode Guide (1954–1990) (series)". tvarchive.ca. Retrieved 2007-11-03.

Bibliography

- Santas, Constantine (2012). The Epic Films of David Lean. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-8210-2.

- Ebert, Roger (8 May 2012). 33 Movies to Restore Your Faith in Humanity: Ebert's Essentials. Andrews McMeel Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4494-2225-7.

- Phillips, Gene (24 November 2006). Beyond the Epic: The Life and Films of David Lean. University Press of Kentucky. p. 255. ISBN 0-8131-7155-5.

- Niemi, Robert (2006). History in the Media: Film and Television. ABC-CLIO. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-57607-952-2.

- Roche, Mark William (1998). Tragedy and Comedy: A Systematic Study and a Critique of Hegel. SUNY Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-7914-3546-5.

- Margulies, Ivone (6 March 2003). Rites of Realism: Essays on Corporeal Cinema. Duke University Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-8223-8461-2.

- Capua, Michelangelo (9 October 2009). William Holden: A Biography. McFarland. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-7864-5550-8.

- Larkin, Brian (10 March 2008). Signal and Noise: Media, Infrastructure, and Urban Culture in Nigeria. Duke University Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-8223-8931-2.

- Ray, Robert Beverley (1985). A Certain Tendency of the Hollywood Cinema, 1930-1980. Princeton University Press. p. 174. ISBN 0-691-10174-4.

- Grimes, Charles W. (1 January 2003). Trademark & Copyright Disputes: Litigation Forms and Analysis. Aspen Publishers Online. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-7355-3515-2.

- Monaco, Paul (2010). A History of American Movies: A Film-by-film Look at the Art, Craft, and Business of Cinema. Scarecrow Press. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-8108-7433-6.

- Roberts, Jonny. How has the representation of World War II on film changed from 1939 to 2009. Jonny Roberts. p. 43. GGKEY:HTN6JK1YKP8.

- Santas, Constantine (2002). Responding to Film: A Text Guide for Students of Cinema Art. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-8304-1580-9.

- Hall, Sheldon (15 April 2010). Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History. Wayne State University Press. p. 168. ISBN 0-8143-3697-3.

- Singh, Dr. Laxman Swaroop. The Obsidian Eye: Cat Journeys Through an Impossible Universe. PublishAmerica. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-4512-2353-8.

- Harris, Mark (14 February 2008). Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-101-20285-2.

- Huda, Anwar (1 January 2004). The Art and Science of Cinema. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 154. ISBN 978-81-269-0348-1.

- Braddock, Jeremy; Hock, Stephen (2001). Directed by Allen Smithee. U of Minnesota Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-8166-3533-7.

- Medavoy, Mike (7 January 2003). You're Only as Good as Your Next One: 100 Great Films, 100 Good Films, and 100 for Which I Should Be Shot. Simon and Schuster. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-7434-0055-8.

- Fuller, Karla Rae (16 August 2010). Hollywood Goes Oriental: CaucAsian Performance in American Film. Wayne State University Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-8143-3538-1.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Bridge on the River Kwai |