The Hours (film)

| The Hours | |

|---|---|

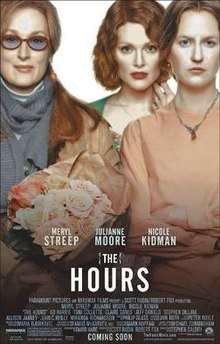

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Stephen Daldry |

| Produced by |

Scott Rudin Robert Fox |

| Screenplay by | David Hare |

| Based on |

The Hours by Michael Cunningham |

| Starring |

Meryl Streep Julianne Moore Nicole Kidman Ed Harris Toni Collette Claire Danes Jeff Daniels Stephen Dillane Allison Janney John C. Reilly Miranda Richardson |

| Music by | Philip Glass |

| Cinematography | Seamus McGarvey |

| Edited by | Peter Boyle |

Production company |

Scott Rudin Productions |

| Distributed by |

Paramount Pictures (North America) Miramax Films (International) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 114 minutes[1] |

| Country |

United Kingdom United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $25 million |

| Box office | $108.8 million |

The Hours is a 2002 British-American drama film directed by Stephen Daldry and starring Meryl Streep, Nicole Kidman, and Julianne Moore. Supporting roles are played by Ed Harris, John C. Reilly, Stephen Dillane, Jeff Daniels, Miranda Richardson, Allison Janney, Toni Collette, Claire Danes, and Eileen Atkins. The screenplay by David Hare is based on Michael Cunningham's 1998 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel of the same title.

The plot focuses on three women of different generations whose lives are interconnected by the novel Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf. These are Clarissa Vaughan (Streep), a New Yorker preparing an award party for her AIDS-stricken long-time friend and poet, Richard (Harris) in 2001; Laura Brown (Moore), a pregnant 1950s California housewife with a young boy and an unhappy marriage; and Virginia Woolf (Kidman) herself in 1920s England, who is struggling with depression and mental illness while trying to write her novel.

The film was released in Los Angeles and New York City on Christmas Day 2002, and was given a limited release in the United States and Canada two days later on December 27, 2002. It did not receive a wide release in North America until January 2003, and was then released in British cinemas on Valentine's Day that year. Critical reaction to the film was largely positive, with nine Academy Award nominations for The Hours including Best Picture, and a win for Nicole Kidman for Best Actress.

Plot

With the exception of the opening and final scenes, which depict the 1941 suicide by drowning of Virginia Woolf in the River Ouse, the action takes place within the span of a single day in three different decades and alternates between them throughout the film. In 1923, Virginia has begun writing the book Mrs Dalloway in her home in the town of Richmond outside London. In 1951, troubled Los Angeles housewife Laura Brown escapes from her conventional life by reading Mrs Dalloway. In 2001, New Yorker Clarissa Vaughan is the embodiment of the novel's title character, as she spends the day preparing for a party she is hosting in honor of her former lover and friend Richard, a poet and author living with AIDS who is to receive a major literary award. Richard tells Clarissa that he has stayed alive for her sake and that the award is meaningless because he didn't get it sooner, until he was on the brink of death. She tells him that she believes that he would have won the award regardless of his illness. Richard often refers to Clarissa as "Mrs. Dalloway" – her namesake – because she distracts herself from her own life the way that the Woolf character does.

Each story in chronological order, not the order as presented in the movie:

1923 -- Virginia, who has experienced several nervous breakdowns and suffers from bipolar disorder, feels trapped in her home. She is intimidated by servants and constantly under the eye of her husband, Leonard, who has begun a publishing business, Hogarth Press, at home to stay close to her. Virginia both welcomes and dreads an afternoon visit from her sister Vanessa and her children. Virginia passionately kisses her sister on the lips. After their departure, Virginia flees to the railway station, where she is awaiting a train to central London, when Leonard arrives to bring her home. He tells her how he lives in constant fear that she will take her own life. She says she fears it also but argues that if she is to live, she has the right to decide how and where.

1951 -- Pregnant with her second child, Laura spends her days in her tract home with her young son, Richie. She married her husband, Dan, soon after World War II. On the surface they are living the American Dream, but she is nonetheless deeply unhappy. She and Richie make a cake for Dan's birthday, but it is a disaster. Her neighbor Kitty drops in to ask her if she can feed her dog while she's in the hospital for a procedure. Kitty reveals that the procedure is related to the fact that she has been unable to conceive, and may portend permanent infertility, and that she really feels that a woman is not complete until she is a mother. Kitty pretends to be upbeat, but Laura senses her sadness and fear and boldly kisses her on the lips; Kitty laughs it off as if it didn't happen. Laura and Richie successfully make another cake and clean up, and then she takes Richie to stay with Mrs. Latch. Richie runs after his mother as she leaves, fearing that she will never come back. Laura checks into a hotel, where she intends to commit suicide. Laura removes several bottles of pills and Mrs. Dalloway from her purse and begins to read it. She drifts off to sleep and dreams the hotel room is flooded. She awakens with a change of heart and caresses her belly. She picks up Richie, and they return home to celebrate Dan's birthday.

2001 -- Clarissa appears equally worried about Richard's depression and the party she is planning for him. Clarissa, who is bisexual and has been living with Sally Lester for 10 years, had been in a relationship with Richard during their college days. She meets with Richard's ex-lover Louis Waters, who has returned for the festivities. Clarissa's daughter, Julia, comes home to help her prepare. Richard has taken a combination of Xanax and Ritalin and tells Clarissa that she is the most beautiful thing that he ever had in life, before he commits suicide in front of her. Later that night, Richard's mother, Laura (the same character from the middle story), arrives at Clarissa's apartment. It is clear that Laura's abandonment of her family was deeply traumatic for Richard, but Laura reveals that it was a better decision for her to leave the family after the birth of her daughter than to commit suicide. She has led an independent, happier life as a librarian in Canada. She does not apologize for the hurt that she caused to her family (Dan and their daughter are also both dead) and suggests that it's not possible to feel regret for something over which she had no choice. She acknowledges that no one will forgive her, but she offers an explanation: "It [her life] was death. I chose life." When Julia visits Laura in her bedroom, she treats her with kindness and sensitivity that Laura does not expect to receive.

The film ends with a voice-over in which Virginia thanks Leonard for loving her: "Always the years between us. Always the years. Always the love. Always the hours."

Cast

- 1923

- Nicole Kidman as Virginia Woolf

- Stephen Dillane as Leonard Woolf

- Miranda Richardson as Vanessa Bell

- Lyndsey Marshal as Lottie Hope

- Linda Bassett as Nelly Boxall

- 1951

- Julianne Moore as Laura Brown

- John C. Reilly as Dan Brown

- Jack Rovello as Richard "Richie" Brown

- Toni Collette as Kitty

- Margo Martindale as Mrs. Latch

- 2001

- Meryl Streep as Clarissa Vaughan

- Ed Harris as Richard "Richie" Brown

- Allison Janney as Sally Lester

- Claire Danes as Julia Vaughan

- Jeff Daniels as Louis Waters

- Julianne Moore as Older Laura Brown

Critical reception

The Hours has an 80% "fresh" rating on the film review aggregator site Rotten Tomatoes based on 192 reviews and an average rating of 7.4/10. The consensus says that "the movie may be a downer, but it packs an emotional wallop. Some fine acting on display here."[2] On Metacritic, the film holds an average score of 80 out of 100, based on 40 reviews.[3] The four main cast members were praised, especially Nicole Kidman who won numerous awards for her portrayal of Virginia Woolf including the Academy Award for Best Actress.

Stephen Holden of The New York Times called the film "deeply moving" and "an amazingly faithful screen adaptation" and added, "Although suicide eventually tempts three of the film's characters, The Hours is not an unduly morbid film. Clear eyed and austerely balanced would be a more accurate description, along with magnificently written and acted. Mr. Glass's surging minimalist score, with its air of cosmic abstraction, serves as ideal connective tissue for a film that breaks down temporal barriers."[4] Mick LaSalle of the San Francisco Chronicle observed, "Director Stephen Daldry employs the wonderful things cinema can do in order to realize aspects of The Hours that Cunningham could only hint at or approximate on the page. The result is something rare, especially considering how fine the novel is, a film that's fuller and deeper than the book ... It's marvelous to watch the ways in which [David Hare] consistently dramatizes the original material without compromising its integrity or distorting its intent ... Cunningham's [novel] touched on notes of longing, middle-aged angst and the sense of being a small consciousness in the midst of a grand mystery. But Daldry and Hare's [film] sounds those notes and sends audiences out reverberating with them, exalted."[5]

Peter Travers of Rolling Stone awarded the film, which he thought "sometimes stumbles on literary pretensions," three out of four stars. He praised the performances, commenting, "Kidman's acting is superlative, full of passion and feeling ... Moore is wrenching in her scenes with Laura's son (Jack Rovello, an exceptional child actor). And Streep is a miracle worker, building a character in the space between words and worlds. These three unimprovable actresses make The Hours a thing of beauty."[6] Richard Schickel of Time criticized its simplistic characterization, saying, "Watching The Hours, one finds oneself focusing excessively on the unfortunate prosthetic nose Kidman affects in order to look more like the novelist. And wondering why the screenwriter, David Hare, and the director, Stephen Daldry, turn Woolf, a woman of incisive mind, into a hapless ditherer."[7]

Philip French of The Observer called it "a moving, somewhat depressing film that demands and rewards attention." He thought "the performances are remarkable" but found the Philip Glass score to be "relentless" and "over-amplified."[8] Steve Persall of the St. Petersburg Times said it "is the most finely crafted film of the past year that I never want to sit through again. The performances are flawless, the screenplay is intelligently crafted, and the overall mood is relentlessly bleak. It is a film to be admired, not embraced, and certainly not to be enjoyed for any reason other than its expertise."[9] Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian rated the film three out of five stars and commented, "It is a daring act of extrapolation, and a real departure from most movie-making, which can handle only one universe at a time . . . The performances that Daldry elicits . . . are all strong: tightly managed, smoothly and dashingly juxtaposed under a plangent score . . . Part of the bracing experimental impact of the film was the absence of narrative connection between the three women. Supplying one in the final reel undermines its formal daring, but certainly packs an emotional punch. It makes for an elegant and poignant chamber music of the soul."[10]

Box office

The Hours opened in New York City and Los Angeles on Christmas Day 2002 and went into limited release in the United States and Canada two days later. It grossed $1,070,856 on eleven screens in its first two weeks of release. On January 10, 2003, it expanded to 45 screens, and the following week it expanded to 402. On February 14 it went into wide release, playing in 1,003 theaters in the US and Canada.[11] With an estimated budget of $25 million, the film eventually earned $41,675,994 in the US and Canada and $67,170,078 in foreign markets for a total worldwide box office of $108,846,072. It was the 47th highest-grossing film of 2002.[11]

Soundtrack

The film's score by Philip Glass won the BAFTA Award for Best Film Music and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Score and the Golden Globe Award for Best Original Score. The soundtrack album was nominated for the Grammy Award for Best Score Soundtrack Album for a Motion Picture, Television or Other Visual Media.

Additional awards and nominations

Further reading

- Taylor, C. J. (2015). The Hours - A film to enhance teaching psychology. Academic Exchange Quarterly, 19(2), 17-22.

References

- ↑ "THE HOURS (12A)". British Board of Film Classification. January 10, 2003. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ↑ "The Hours". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ↑ "The Hours". Metacritic. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ↑ Holden, Stephen (December 27, 2002). "''New York Times'' review". Nytimes.com. Archived from the original on December 4, 2009. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ↑ Mick LaSalle; Chronicle Movie Critic (December 27, 2002). "''San Francisco Chronicle'' review". Sfgate.com. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ↑ Rolling Stone review

- ↑ RICHARD SCHICKEL Monday, December 23, 2002 (December 23, 2002). "''Time'' review". Time.com. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ↑ Phillip French (February 16, 2003). "''The Observer'' review". London: Guardian. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ↑ "''St. Petersburg Times'' review". Sptimes.com. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ↑ Peter Bradshaw (February 14, 2003). "''The Guardian'' review". London: Guardian. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- 1 2 "The Hours". Box Office Mojo. December 27, 2002. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Hours |