The Lion in Winter (1968 film)

| The Lion in Winter | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Anthony Harvey |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by | James Goldman |

| Based on |

The Lion in Winter by James Goldman |

| Starring | |

| Music by | John Barry |

| Cinematography | Douglas Slocombe |

| Edited by | John Bloom |

Production company |

AVCO Embassy Pictures Haworth Productions |

| Distributed by | AVCO Embassy Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 134 minutes |

| Country |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $4 million[1] |

| Box office | $22.3 million[2] |

The Lion in Winter is a 1968 historical period drama film based on the Broadway play of the same name by James Goldman. It was directed by Anthony Harvey, written by James Goldman, and produced by Joseph E. Levine, Jane C. Nusbaum and Martin Poll from Goldman's adaptation of his own play, The Lion in Winter. The film stars Peter O'Toole, Katharine Hepburn, John Castle, Anthony Hopkins (in his film debut in a major role), Jane Merrow, Timothy Dalton (in his film debut) and Nigel Terry.

The film was a commercial success (the 12th highest-grossing film of 1968) and won three Academy Awards, including one for Hepburn as Best Actress (tied with Barbra Streisand). There was a television remake in 2003.

Plot

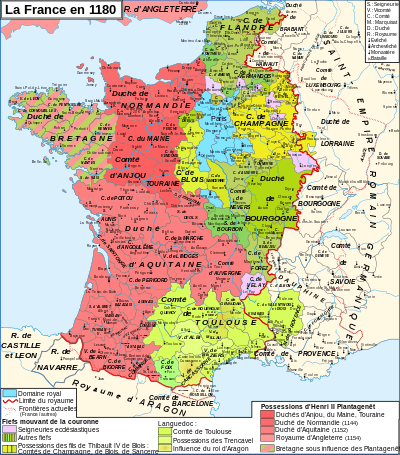

The Lion in Winter is set during Christmas 1183, at King Henry II's château and primary residence in Chinon, Anjou, in the medieval Angevin Empire. Henry wants his youngest son, the future King John, to inherit his throne, while his estranged and imprisoned wife, Duchess Eleanor of Aquitaine, temporarily released from prison for the holidays, favors their oldest surviving son, the future King Richard the Lionheart. Meanwhile, King Philip II of France, the son and successor of Louis VII of France, Eleanor's ex-husband, has given his half-sister Alais, who is currently Henry's mistress, to the future heir, and demands either a wedding or the return of her dowry.

As a ruse, Henry agrees to give Alais to Richard and make him heir-apparent. He makes a side deal with Eleanor for her freedom in return for Aquitaine, to be given to John. When the deal is revealed at the wedding, Richard refuses to go through with the ceremony. After Richard leaves, Eleanor masochistically asks Henry to kiss Alais in front of her, and then looks on in horror as they perform a mock marriage ceremony. Having believed Henry's intentions, John, at the direction of middle brother, Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany, plots with Philip to make war on England. Henry and Philip meet to discuss terms, but Henry soon learns that Phillip has been plotting with John and Geoffrey, and that he and Richard were once lovers.

Henry dismisses all three sons as unsuitable, and locks them in a wine cellar, telling Alais, "the royal boys are aging with the royal port."[3] He makes plans to travel to Rome for an annulment, so that he can have new sons with Alais, but she says he will never be able to release his sons from prison or they will be a threat to his future children. Henry sees that she is right and condemns them to death, but cannot bring himself to kill them, instead letting them escape. He and Eleanor go back to hoping for the future, with Eleanor going back on the barge to prison, laughing it off with Henry before she leaves.

Historical background

Though the background and the eventual destinies of the characters are generally historically accurate, The Lion in Winter is fictional; none of the dialogue or action is historical. There was a Christmas court at Caen in 1182 but there was no Christmas court at Chinon in 1183. In reality, Henry had many mistresses and many illegitimate children; the "Rosamund" mentioned in the film was his mistress until she died. The article on the Revolt of 1173–1174 describes the historical events leading to the play's events. There was also a second rebellion, when Young Henry and Geoffrey revolted in 1183, resulting in Young Henry's death. While some historians have theorized that Richard was homosexual, historians remain divided on the question.

Geoffrey died in 1186 in a jousting tournament held in Paris (with some speculation that Geoffrey was involved in plotting against Henry with Philip at the time). A third rebellion against Henry by Richard and Philip in 1189 was finally successful, and a decisively defeated Henry retreated to Chinon in Anjou, where he died. Richard the Lionheart succeeded Henry II, but spent very little time in England (perhaps 6 months) after which he became a central Christian commander during the Third Crusade, leading the campaign after the departure of Philip. Richard scored considerable victories but did not succeed in retaking Jerusalem. John finally succeeded Richard in 1199 after Richard's death. During his unsuccessful reign he lost most of his father's holdings in Northern France and angered the barons, who revolted and forced him to sign the Magna Carta. John is also known for being the villain in the Robin Hood legends. Lastly, Captain William Marshall, who during the film is harried about by Henry II, outlived the English royal family and eventually ruled England as regent for the young Henry III.[4]

Cast

- Peter O'Toole as King Henry II, King of England, Lord of Ireland, Duke of Normandy and of Aquitaine, Count of Anjou

- Katharine Hepburn as Eleanor of Aquitaine, his estranged Queen

- Anthony Hopkins as Richard the Lionheart, their eldest surviving son

- John Castle as Geoffrey, their middle surviving son

- Nigel Terry as John, their youngest surviving son

- Timothy Dalton as King Philip II of France

- Jane Merrow as Alais, Henry's mistress, betrothed to Richard

- Nigel Stock as Captain William Marshall

- Kenneth Ives as Queen Eleanor's guard

- O. Z. Whitehead as Hugh de Puiset, the Bishop of Durham

Background and production

The original stage production had not been a success, getting a bad review in the New York Times and losing $150,000. Producer Martin Poll optioned Goldman's novel Waldorf for the movies. They discussed Lion in Winter which Poll read and loved. He hired Goldman to write a screenplay. Poll was meant to make a film with Joseph Levine and Peter O'Toole, The Ski Bum. That project fell through and Poll suggested they do Lion in Winter instead.[5]

In October 1967, the actors rehearsed at Haymarket Theatre in London.[6] Production started in November 1967[7] and continued until May 1968.[8]

The film was shot at Ardmore Studios in Bray, County Wicklow, Ireland, and on location in Ireland, Wales (Marloes Sands),[9] and in France at Abbaye de Montmajour, Arles, Château de Tarascon, Tarascon and Tavasson, Saône-et-Loire. The film debuted on 30 October 1968 (29 December 1968 London premiere).

O'Toole, who was 36, portrays Henry II at age 50. He had played the same king as a young man in the film Becket just four years earlier.

The sculpted stone figures appearing during the main title music were a lucky, unexpected find by the director while shooting scenes in France. They were filmed along the artist's driveway and later edited to create the title sequence where they appear to be on interior walls of the castle.[10]

Reception

The film earned an estimated $6.4 million in distributor rentals in the domestic North American market during its initial year of release.[11] It was the 14th most popular movie at the U.S. box office in 1969.[12]

Review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes retrospectively collected 36 reviews, and gave the film an approval rating of 92% and an average rating of 8.3/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Sharper and wittier than your average period piece, The Lion in Winter is a tale of palace intrigue bolstered by fantastic performances from Peter O'Toole, Katharine Hepburn, and Anthony Hopkins in his big-screen debut."[13]

Preservation

The Academy Film Archive preserved The Lion in Winter in 2000.[14]

Awards and honors

Academy Awards

The film received three awards out of seven nominations.

- Best Actress — Win for Katharine Hepburn, tied with Barbra Streisand for Funny Girl (the only time this has happened for actresses in Academy history)

- Best Adapted Screenplay — Win for James Goldman

- Best Music Score — Win for John Barry (composer)

- Best Picture — Nomination for Martin Poll and Joseph E. Levine

- Best Director — Nomination for Anthony Harvey

- Best Actor — Nomination for Peter O'Toole

- Best Costume Design — Nomination for Margaret Furse

BAFTA Awards

The film received two wins out of seven nominations.

- Best Actress — Win for Katharine Hepburn, jointly awarded with Hepburn's performance in Guess Who's Coming to Dinner

- Anthony Asquith Award for Film Music — Win for John Barry

- Best Cinematography — Nomination for Douglas Slocombe

- Best Costume Design — Nomination for Margaret Furse

- Best Screenplay — Nomination for James Goldman

- Best Sound Track — Nomination for Chris Greenham

- Best Supporting Actor — Nomination for Anthony Hopkins

Golden Globe Awards

The film received two wins out of seven nominations.

- Best Motion Picture—Drama — Win (Martin Poll, Joseph E. Levine)

- Best Actor — Win for Peter O'Toole

- Best Actress — Nomination for Katharine Hepburn

- Best Motion Picture Director — Nomination for Anthony Harvey

- Best Original Score — Nomination for John Barry

- Best Screenplay — Nomination for James Goldman

- Best Supporting Actress — Nomination for Jane Merrow

Other awards

British Society of Cinematographers

- Best Cinematography — Win for Douglas Slocombe

- Best Foreign Production — Win for Martin Poll and Joseph E. Levine

Directors Guild of America Awards

- Outstanding Directorial Achievement — Win for Anthony Harvey

- Best Female Dramatic Performance — Win for Katharine Hepburn

- Best Drama — Nomination

New York Film Critics Circle Awards

- Best Film — Win

Writers' Guild of Great Britain

- Best British Screenplay — Win for James Goldman

Writers Guild of America Awards

- Best Written American Drama — Win for James Goldman

See also

References

- ↑ Joseph, Robert. "Films Come to the Emerald Isle: Emerald Isle Welcomes Films" Los Angeles Times (1923-Current File) [Los Angeles, Calif] 17 March 1968: q26.

- ↑ "The Lion in Winter (1968)". The Numbers. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- ↑ Quote from the 1968 movie, The Lion in Winter.

- ↑ Painter, S., William Marshal, Knight-Errant, Baron & Regent of England, p.268

- ↑ Smith, C. (1968, Dec 01). 'Lion in winter'--play that refused to die. Los Angeles Times (1923-Current File) Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/156111474

- ↑ Bergan 1996, p. 155.

- ↑ Callan 2004, pp. 90, 100, 105.

- ↑ Wapshott 1984, p. 145.

- ↑ Wales hosts Hollywood blockbusters

- ↑ Director Anthony Harvey, audio commentary in Lion in Winter, 2000.

- ↑ "Big Rental Films of 1969", Variety, 7 January 1970 p 15

- ↑ "The World's Top Twenty Films", Sunday Times, [London, England], 27 September 1970: 27. The Sunday Times Digital Archive. accessed 5 April 2014

- ↑ "The Lion in Winter (1968)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ "Preserved Projects". Academy Film Archive.

Bibliography

- Paden, William (2004). Utz, Richard; Swan, Jesse G, eds. I Learned It at the Movies: Teaching Medieval Film in: Postmodern Medievalisms. Cambridge: Brewer. pp. 79–98.

- Bergan, Ronald (1996). Katharine Hepburn: An Independent Woman. Arcade Publishing. p. 155. ISBN 9781559703512.

- Callan, Michael Feeney (2004). Anthony Hopkins: A Three Act Life. London: Robson Books. pp. 98, 100, 105. ISBN 186105761X.

- Wapshott, Nicholas (1984). Peter O'Toole: A Biography. Beaufort Books. p. 145. ISBN 9780825301964.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Lion in Winter (1968 film) |