Arminiya

| Emirate of Armenia | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 654–884 | |||||||||||||||||||

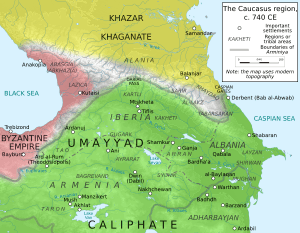

Map of the Caucasus and of Arminiya c. 740 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Province (largely autonomous vassal principalities) of the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates | ||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Dvin | ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages |

Armenian (native language) Arabic | ||||||||||||||||||

| Religion |

Armenian Apostolic Christianity Sunni Islam Paulicianism | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||||||||||

• Established | 654 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 884 | ||||||||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | AM | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Arminiya, also known as the Ostikanate of Arminiya (Armenian: Արմինիա ոստիկանություն,[1] Arminia vostikanut'yun), Emirate of Armenia (Arabic: إمارة أرمينيا, imārat Arminiya), was a political and geographic designation given by the Muslim Arabs to the lands of Greater Armenia, Caucasian Iberia, and Caucasian Albania, following their conquest of these regions in the 7th century. Though the caliphs initially permitted an Armenian prince to represent the province of Arminiya in exchange for tribute and the Armenians' loyalty during times of war, Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan introduced direct Arab rule of the region, headed by an ostikan with his capital in Dvin.

History

Early period

The first Arab expedition reached Armenia in 639 AD.[2] Dvin was captured and pillaged during this raid on 6 October 640. According to bishop Sebeos, in 641, the Arabs took the city of Tovin (Duin) by storm, killing 12,000 Armenians and taking 35,000 as captives. A third invasion took place in 642–643 and a fourth in 650, which captured some land north of Lake Van.[3]

Armenia however remained under Byzantine suzerainty until 653/654, when Theodore Rshtuni voluntarily conceded Arab suzerainty and was recognized as autonomous prince of Armenia in return. According to this agreement, Armenia was recognized as an autonomous state subject to an annual tribute and a contribution of fifteen thousand troops to the Arab army. With Arab aid, Rhstuni repelled Byzantine attacks, and Arab troops even captured Theodosiopolis in 655, and cemented their control of the country by taking Rhstuni to Damascus and appointing his rival Hamazasp Mamikonian in his stead.

The outbreak of the Muslim Civil War in 657 led to the recall of the Arab troops to Syria. Thereupon the Byzantines re-asserted their authority over the country, aided by Mamikonian.

In 661 however, the victor of the Muslim civil war Mu'awiyah ordered the Armenian princes to re-submit to his authority and pay tribute. In order to avoid another war, the princes complied. The Arab policy of demanding that the tribute be paid in money had an effect on Armenian economy and society. Coins were struck in Dvin. The Armenians were forced to produce a surplus of food and manufactured goods for sale. A strong urban life was developed in Caucasia as the economy revived.Area 300 000 KM2.

Establishment of direct Muslim control

For most of the second half of the 7th century, Arab presence and control in Armenia was minimal. Armenia was considered conquered land by the Arabs, but enjoyed de facto autonomy, regulated by the treaty signed between Rhstuni and Mu'awiyah in 654. The Armenian princes were submitted to—relatively low—taxation and the obligation to provide soldiers when requested, for which the princes were to be paid an annual subsidy of 100,000 dirhams. In exchange, no Arab garrison or official was installed in Armenian lands, and Arab assistance was even promised in the event of Byzantine attack.[4][5] The situation changed in the reign of the caliph Abd al-Malik (r. 685–705). Beginning in 700, the Caliph's brother and governor of Adharbayjan (modern Iranian Azerbaijan), Muhammad ibn Marwan, subdued the country in a series of campaigns. Although the Armenians rebelled in 703 and received Byzantine aid, Muhammad ibn Marwan defeated them and sealed the failure of the revolt by executing the rebel princes in 705.[4][6] Armenia, along with the principalities of Caucasian Albania and Caucasian Iberia (modern Georgia) was grouped into one vast province called al-Arminiya (الارمينيا), with its capital at Dvin (Arabic Dabil), which was rebuilt by the Arabs and served as the seat of the governor (ostikan) and of an Arab garrison.[4][6] For much of the remaining Umayyad period, Arminiya was usually grouped together with Adharbayjan and the Jazira into a single super-province.[7]

Arminiya was governed by an emir or wali headquartered at Dvin, whose role however was limited to defence and the collection of taxes: the country was largely run by the local princes, the nakharar. The province was formally established . The Emirate of Armenia (al-Arminiya) was divided into four regions: Arminiya I (Caucasian Albania), Arminiya II (Caucasian Iberia), Arminiya III (the area around Aras River), Arminiya IV (Taron).[8] The local nobility was headed, as in Sasanian times, by a prince (ishkhan), a title which in the 9th century, beginning probably with Bagrat II Bagratuni, evolved into the title of "prince of princes" or "presiding prince" (ishkhan ishkhanats′). Acting as the head of the other princes, the ishkhan was answerable to the Arab governor, being responsible for the collection of the taxes owed to the caliphal government and the raising of military forces when requested.[9]

A census and survey of Arminiya was undertaken c. 725, followed by a significant increase in taxation so as to finance the Caliphate's increasing military needs in the various fronts.[10] The Armenians participated with troops in the hard-fought campaigns of the Arab–Khazar wars in the 720s and 730s. As a result, in 732, governor Marwan ibn Muhammad (the future Caliph Marwan II) named Ashot III Bagratuni as the presiding prince of Armenia, an act which essentially re-confirmed the country's autonomy within the Caliphate.[11]

Abbasid period until 884

With the establishment of the Abbasid Caliphate after the Abbasid Revolution, a period of repression was inaugurated: al-Saffar the Amir of the Saffarid dynasty subdued the Armenian rebellion of 747–750 with great brutality. This was followed by Caliph al-Mansur revoking the privileges and abolishing the subsidies paid to the various Armenian princes (the nakharars) and imposing harsher taxation, leading to the outbreak of another major rebellion in 774. The revolt was suppressed in the Battle of Bagrevand in April 775.[12][13] The failure of the rebellion saw the near-extinction, reduction to insignificance or exile to Byzantium of some of the most prominent nakharar families, most importantly the Mamikonian. In its aftermath, the Caliphate tightened its grip on the Transcaucasian provinces: the nobility of neighbouring Iberia was also decimated in the 780s, and a process of settlement with Arab tribes began which by the middle of the 9th century led to the Islamization of Caucasian Albania, while Iberia and much of lowland Armenia came under the control of a series of Arab emirates. At the same time, the power vacuum left by the destruction of so many nakharar clans was filled by two other great families, the Artsruni in the south (Vaspurakan) and the Bagratuni in the north.[14][15]

Despite several insurrections, the Emirate of Armenia lasted until 884, when the Bagratuni Ashot I, who had managed to win control over most of its area, declared himself "King of the Armenians". He received recognition by Caliph Al-Mu'tamid of the Abbasid dynasty in 885 and Byzantine Emperor Basil I of the Macedonian dynasty in 886.

Ashot was swiftly able to expand his power. Through family links with the two next most important princely families, the Artsruni and the Siwnis, and through a cautious policy towards the Abbasids and the Arab emirates of Armenia, by the 860s he had succeeded in becoming in fact, if not yet in name, an autonomous king. [16]

Arab governors of Armenia

Early governors

These are reported as governors under the Caliphs Uthman (r. 644–656) and Ali (r. 656–661), as well as the early Umayyads:

- Hudaifa ibn al-Yaman

- al-Mughira ibn Shu'ba

- al-Qasim ibn Rabi'a ibn Umayya ibn Abi's al-Thaqafi

- Habib ibn Maslama al-Fihri

- al-As'ath ibn Qays al-Kindi (ca. 657)

- Muhallab ibn Abi Sufra (ca. 686)

Emirs (Ostikans)

With the submission of Armenia to Muhammad ibn Marwan after 695, the province was formally incorporated into the Caliphate, and an Arab governor (ostikan) installed at Dvin:[17][18]

- Muhammad ibn Marwan (c. 695–705), represented by the following deputies:

- Uthman ibn al-Walid ibn 'Uqba ibn Aban Abi Mu 'ayt

- Abdallah ibn Hatim al-Bahili

- Abd al-Aziz ibn Hatim al-Bahili (706–709)

- Maslamah ibn Abd al-Malik (709–721)

- al-Djarrah ibn Abdallah al-Hakami (721–725)

- Maslamah ibn Abd al-Malik (725–729)

- al-Djarrah ibn Abdallah al-Hakami (729–730)

- Maslamah ibn Abd al-Malik (730–732)

- Marwan ibn Muhammad (732–733)

- Sa'id ibn Amr al-Harashi (733–735)

- Marwan ibn Muhammad (735–744)

- Ishaq ibn Muslim al-Uqayli (744–750)

- Abu Ja'far Abdallah ibn Muhammad (750–753)

- Yazid ibn Asid ibn Zafir al-Sulami (753–755)

- Sulayman (755–?)

- Salih ibn Subai al-Kindi (c. 767)

- Bakkar ibn Muslim al-Uqayli (c. 769–770)

- al-Hasan ibn Qahtaba (770/771–773/774)

- Yazid ibn Asid ibn Zafir al-Sulami (773/774–778)

- Uthman ibn 'Umara ibn Khuraym (778–785)

- Khuzayma ibn Khazim (785–786)

- Yusuf ibn Rashid al-Sulami (786–787)

- Yazid ibn Mazyad al-Shaybani (787–788)

- Abd al-Qadir (788)

- Sulayman ibn Yazid (788–799)

- Yazid ibn Mazyad al-Shaybani (799–801)

- Asad ibn Yazid al-Shaybani (801–802)

- Muhammad ibn Yazid al-Shaybani (802–803)

- Khuzayma ibn Khazim (803–?)

- Asad ibn Yazid al-Shaybani (c. 810)

- Ishaq ibn Sulayman (c. 813)

- Khalid ibn Yazid ibn Mazyad al-Shaybani (813–?) (828–832), (841), (c. 842-844)

- Muhammad ibn Khalid al-Shaybani (c. 842/844–?)

- Abu Sa'id Muhammad al-Marwazi (849–851)

- Yusuf ibn Abi Sa'id al-Marwazi (851–852)

- Bugha al-Kabir (852–855)

- Muhammad ibn Khalid al-Shaybani (857–862)

- Ali ibn Yahya al-Armani (862–863)

- al-Abbas ibn al-Musta'in (863–865)

- Abdallah ibn al-Mu'tazz (866–867)

- Abi'l-Saj Devdad (867–870)

- Isa ibn al-Shaykh al-Shaybani (870–875, nominally until 882/3)

- Ja'far al-Mufavvid (875-878)

- Muhammad ibn Khalid al-Shaybani (878)

Presiding princes of Armenia

- Mjej II Gnuni Մժեժ Բ Գնունի, 628–635

- David Saharuni Դավիթ Սահառունի, 635–638

- Theodore Rshtuni Թէոդորոս Ռշտունի, 638–645

- Varaztirots II Bagratuni Վարազ Տիրոց Բ Բագրատունի, 645

- Theodore Rshtuni Թէոդորոս Ռշտունի, 645–653, 654–655

- Mushegh II Mamikonian Մուշէղ Բ Մամիկոնեան, 654

- Hamazasp II Mamikonian Համազասպ Բ Մամիկոնեան, 655–658

- Gregory I Mamikonian Գրիգոր Ա Մամիկոնեան, 662–684/85

- Ashot II Bagratuni Աշոտ Բ Բագրատունի, 686–690

- Nerses Kamsarakan Ներսէս Կամսարական, 689–691

- Smbat VI Bagratuni Սմբատ Զ Բագրատունի, 691–711

- Ashot III Bagratuni Աշոտ Գ Բագրատունի, 732–748

- Gregory II Mamikonian Գրիգոր Բ Մամիկոնեան, 748–750

- Sahak VII Bagratuni Սահակ Է Բագրատունի, 755–761

- Smbat VII Bagratuni Սմբատ Է Բագրատունի, 761–775

- Ashot IV Bagratuni Աշոտ Դ Բագրատունի, 806–826

- Bagrat II Bagratuni Բագրատ Բ Բագրատունի, 830–851

- Ashot V Bagratuni Աշոտ Ա Հայոց Արքայ, Աշոտ Ե իշխան Հայոց, 862–884

See also

Notes

- ↑ Yeghiazaryan, Arman (2005). "Արմինիա ոստիկանության սահմանները [Borders of the Vicegerency of Arminia]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences (1): 243–258. ISSN 0135-0536.

- ↑ Morgan 1918, p. 139.

- ↑ Histoire d’Héraclius. Trancl. Fr. Macler, Paris, 1904. page 101

- 1 2 3 Ter-Ghewondyan 1976, p. 20.

- ↑ Whittow 1996, p. 211.

- 1 2 Blankinship 1994, p. 107.

- ↑ Blankinship 1994, pp. 52–54.

- ↑ Robert H. Hewsen. Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Univ. of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2001, 107, map 81.

- ↑ Jones 2007, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Blankinship 1994, pp. 123–124.

- ↑ Blankinship 1994, p. 153.

- ↑ Ter-Ghewondyan 1976, p. 21.

- ↑ Whittow 1996, p. 213.

- ↑ Ter-Ghewondyan 1976, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Whittow 1996, pp. 213–215.

- ↑ Ter-Ghewondyan 1976, pp. 53ff..

- ↑ Arab Governors (Ostikans) of Arminiya, 8th Century Archived October 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ A. Ter-Ghevondyan's "Chronology of the Ostikans of Arminiya," Patma-banasirakan handes (1977) 1, pp. 117-128.

Sources

- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1994). The End of the Jihâd State: The Reign of Hishām ibn ʻAbd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1827-7.

- Jones, Lynn (2007). Between Islam and Byzantium: Aght'amar and the Visual Construction of Medieval Armenian Rulership. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0754638529.

- Laurent, Joseph L. (1919). L’Arménie entre Byzance et l'Islam: depuis la conquête arabe jusqu'en 886 (in French). Paris: De Boccard.

- Morgan, Jacques de (1918), The History of the Armenian People: From the remotest times to the present day, Barry, Ernest F., trans., Boston: Hairenik Press

- Ter-Ghewondyan, Aram (1976). The Arab Emirates in Bagratid Armenia. Transl. Nina G. Garsoïan. Lisbon: Livraria Bertrand. OCLC 490638192.

- Whittow, Mark (1996). The Making of Byzantium, 600–1025. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20496-6.

- Robert H. Hewsen. Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Univ. of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2001, Pp. 341.

- Garbis Armen. Historical Atlas of Armenia. A. N. E. C., New York, 1987, Pp. 52.

- George Bournoutian. A History of the Armenian People, Volume I: Pre-History to 1500 AD, Mazda Publishers, Costa Mesa, 1993, Pp. 174.

- John Douglas. The Armenians, J. J. Winthrop Corp., New York, 1992.