Politics of Armenia

| |

| State type | Unitary parliamentary republic |

|---|---|

| Constitution | Constitution of Armenia |

| Legislative branch | |

| Name | National Assembly |

| Type | Unicameral |

| Meeting place | National Assembly Building |

| Presiding officer |

Ara Babloyan President of the National Assembly |

| Executive branch | |

| Head of State | |

| Title | President |

| Currently | Armen Sarkissian |

| Appointer | National Assembly |

| Head of Government | |

| Title | Prime Minister |

| Currently | Nikol Pashinyan |

| Appointer | President |

| Cabinet | |

| Name | Government of Armenia |

| Appointer | President |

| Headquarters | Government House |

| Ministries | 17 |

| Judicial branch | |

| Name | Judiciary of Armenia |

| Part of a series on |

| Armenia Հայաստան |

|---|

|

| Culture |

| History |

| Demographics |

| Administrative divisions |

|

| Armenia portal |

The politics of Armenia take place in the framework of the parliamentary representative democratic republic of Armenia, whereby the President of Armenia is the head of state and the Prime Minister of Armenia the head of government, and of a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the President and the Government. Legislative power is vested in both the Government and Parliament.[1][2][3]

History

Armenia became independent from the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic on 28 May 1918 as the First Republic of Armenia. After the First Republic collapsed on 2 December 1920, it was absorbed into the Soviet Union and became part of the Transcaucasian SFSR. The TSFSR dissolved in 1936 and Armenia became a constituent republic of the Soviet Union known as the Armenian SSR.

The population of Armenia voted overwhelmingly for independence in a September 1991 referendum, followed by a presidential election in October 1991 that gave 83% of the vote to Levon Ter-Petrosyan. Ter-Petrosyan had been elected head of government in 1990, when the National Democratic Union party defeated the Armenian Communist Party. Ter-Petrosyan was re-elected in 1996. Following public demonstrations against Ter-Petrosyan's policies on Nagorno-Karabakh, the President resigned in January 1998 and was replaced by Prime Minister Robert Kocharyan, who was elected President in March 1998. Following the assassination in Parliament of Prime Minister Vazgen Sargsyan and parliament Speaker Karen Demirchyan and six other officials, on 27 October 1999, a period of political instability ensued during which an opposition headed by elements of the former Armenian National Movement government attempted unsuccessfully to force Kocharyan to resign. Kocharyan was successful in riding out the unrest. In May 2000, Andranik Margaryan replaced Aram Sargsyan as Prime Minister.

Kocharyan's re-election as president in 2003 was followed by widespread allegations of ballot-rigging. He went on to propose controversial constitutional amendments on the role of parliament. These were rejected in a referendum the following May at the same time as parliamentary elections which left Kocharyan's party in a very powerful position in parliament. There were mounting calls for the President's resignation in early 2004 with thousands of demonstrators taking to the streets in support of demands for a referendum of confidence in him.

The unicameral parliament (also called the National Assembly) is dominated by a coalition, called "Unity" (Miasnutyun), between the Republican and Peoples Parties and the Agro-Technical Peoples Union, aided by numerous independents. Dashnaksutyun, which was outlawed by Ter-Petrosyan in 1995–96 but legalized again after Ter-Petrosyan resigned, also usually supports the government. A new party, the Republic Party, is headed by ex-Prime Minister Aram Sargsyan, brother of Vazgen Sargsyan, and has become the primary voice of the opposition, which also includes the Armenian Communist Party, the National Unity party of Artashes Geghamyan, and elements of the former Ter-Petrosyan government.

The Government of Armenia's stated aim is to build a Western-style parliamentary democracy as the basis of its form of government. However, international observers have questioned the fairness of Armenia's parliamentary and presidential elections and constitutional referendum since 1995, citing polling deficiencies, lack of cooperation by the Electoral Commission, and poor maintenance of electoral lists and polling places. For the most part however, Armenia is considered one of the more pro-democratic nations in the Commonwealth of Independent States. Observers noted, though, that opposition parties and candidates have been able to mount credible campaigns and proper polling procedures have been generally followed. Elections since 1998 have represented an improvement in terms of both fairness and efficiency, although they are still considered to have fallen short of international standards. The new constitution of 1995 greatly expanded the powers of the executive branch and gives it much more influence over the judiciary and municipal officials.

The observance of human rights in Armenia is uneven and is marked by shortcomings. Police brutality allegedly still goes largely unreported, while observers note that defendants are often beaten to extract confessions and are denied visits from relatives and lawyers. Public demonstrations usually take place without government interference, though one rally in November 2000 by an opposition party was followed by the arrest and imprisonment for a month of its organizer. Freedom of religion is not always protected under existing law. Nontraditional churches, especially the Jehovah's Witnesses, have been subjected to harassment, sometimes violently. All churches apart from the Armenian Apostolic Church must register with the government, and proselytizing was forbidden by law, though since 1997 the government has pursued more moderate policies. The government's policy toward conscientious objection is in transition, as part of Armenia's accession to the Council of Europe. Most of Armenia's ethnic Azeri population was deported in 1988–1989 and remain refugees, largely in Azerbaijan. Armenia's record on discrimination toward the few remaining national minorities is generally good. The government does not restrict internal or international travel. Although freedom of the press and speech are guaranteed, the government maintains its monopoly over television and radio broadcasting.

Change to a parliamentary republic

In December 2015, the country held a referendum which approved transformation of Armenia from a semi-presidential to a parliamentary republic.[4]

As a result, the president is stripped of his veto faculty and the presidency is downgraded to a figurehead position elected by parliament every seven years. The president is not allowed to be a member of any political party and re-election is forbidden. Having more immediate effects, the amendments reduced the number of parliamentary seats from 131 to 101.[5]

Sceptics saw the constitutional reform as an attempt of third president Serzh Sargsyan to remain in control by becoming prime minister after fulfilling his second presidential term in 2018.[4]

Government

Until the ratification of the 2015 constitutional reform, the President was directly elected for a five-year term in a two-round system.

| Office | Name | Party | Since |

|---|---|---|---|

| President of Armenia | Armen Sarkissian | Independent | 9 April 2018 |

| Prime Minister | Nikol Pashinyan | Way Out Alliance | 8 May 2018 |

Legislative branch

The unicameral National Assembly of Armenia (Azgayin Zhoghov) is the legislative branch of the government of Armenia.

Before 2015 constitutional referendum it was initially made of 131 members, elected for five-year terms: 90 members in single-seat constituencies and 41 by proportional representation. The proportional-representation seats in the National Assembly are assigned on a party-list basis amongst those parties that receive at least 5% of the total of the number of the votes.

Following the 2015 referendum, the number of MPs was reduced from the original 131 members to 101 and single-seat constituencies were removed.[5]

Political parties and elections

The electoral threshold is currently set at 5% for single parties and 7% for blocs.[6]

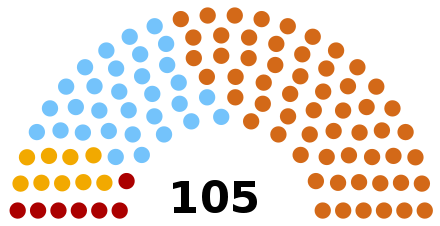

| |||||

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | |

| Republican Party | 771,247 | 49.17 | 58 | ||

| Tsarukyan Alliance | 428,965 | 27.35 | 31 | ||

| Way Out Alliance | 122,049 | 7.78 | 9 | ||

| ARF | 103,173 | 6.58 | 7 | ||

| Armenian Renaissance | 58,277 | 3.72 | 0 | ||

| ORO Alliance (Ohanyan-Raffi-Oskanian) | 32,504 | 2.07 | 0 | ||

| ANC–PPA Alliance | 25,975 | 1.66 | 0 | ||

| Free Democrats | 14,746 | 0.94 | 0 | ||

| Armenian Communist Party | 11,745 | 0.75 | 0 | ||

| Invalid votes | 6,701 | — | — | — | |

| Total | 1,575,382 | 100.00 | 105 | — | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electorate and turnout: | 2,588,590 | 60.86 | — | — | |

| Source: Central Electoral Commission of the Republic of Armenia | |||||

The first primary election in Armenia was held by the Armenian Revolutionary Federation in November 2007 to select the presidential candidate. Some 300.000 people voted.[7][8]

| Candidates | Nominating parties | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serzh Sargsyan | Republican | 861,160 | 58.64 | |

| Raffi Hovannisian | Heritage | 539,672 | 36.75 | |

| Hrant Bagratyan | Freedom | 31,643 | 2.15 | |

| Paruyr Hayrikyan | UNSD | 18,093 | 1.23 | |

| Andrias Ghukasyan | none | 8,328 | 0.57 | |

| Vardan Sedrakyan | none | 6,203 | 0.42 | |

| Arman Melikyan | none | 3,516 | 0.24 | |

| Valid votes | 1,468,615 | 96.64 | ||

| Invalid votes | 50,988 | 3.36 | ||

| Total votes | 1,519,603 | 100.00 | ||

| Voters/turnout | 2,528,773 | 60.09 | ||

| Source: Central Electoral Commission | ||||

Independent agencies

Independent of three traditional branches are the following independent agencies, each with separate powers and responsibilities:[9]

- the Constitutional Court of Armenia

- the Central Electoral Commission of the Republic of Armenia

- the Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Armenia

- the Central Bank of Armenia

- the General Prosecutor's Office

- the Control Chamber of The Republic of Armenia

Corruption

Political corruption is a problem in Armenian society. In 2008, Transparency International reduced its Corruption Perceptions Index for Armenia from 3.0 in 2007[10] to 2.9 out of 10 (a lower score means more perceived corruption); Armenia slipped from 99th place in 2007 to 109th out of 180 countries surveyed (on a par with Argentina, Belize, Moldova, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu).[11] Despite legislative revisions in relation to elections and party financing, corruption either persists or has re-emerged in new forms.[12]

The United Nations Development Programme in Armenia views corruption in Armenia as "a serious challenge to its development."[13]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Shugart, Matthew Søberg (September 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive and Mixed Authority Patterns" (PDF). Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies. United States: University of California, San Diego. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ↑ Shugart, Matthew Søberg (December 2005). "Semi-Presidential Systems: Dual Executive And Mixed Authority Patterns" (PDF). Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies, University of California, San Diego. French Politics. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. 3 (3): 323–351. doi:10.1057/palgrave.fp.8200087. ISSN 1476-3427. OCLC 6895745903. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

Table 1 shows that dissolution power as a presidential initiative is rare in the contemporary president-parliamentary systems. In fact, only in Armenia may the president dissolve (once per year) without a trigger (e.g. assembly failure to invest a government).

- ↑ Markarov, Alexander (2016). "Semi-presidentialism in Armenia" (PDF). In Elgie, Robert; Moestrup, Sophia. Semi-Presidentialism in the Caucasus and Central Asia. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK (published 15 May 2016). pp. 61–90. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-38781-3_3. ISBN 978-1-137-38780-6. LCCN 2016939393. OCLC 6039792321. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

Markarov discusses the formation and development of the semi-presidential system in Armenia since its foundation in 1991. The author identifies and compares the formal powers of the president, prime minister, and parliament under the 1995 Constitution as well as the amendments introduced through the Constitutional referendum in 2005. Markarov argues that the highly presidentialized semi-presidential system that was introduced in the early 1990s gradually evolved into a Constitutionally more balanced structure. However, in practice, the president has remained dominant and backed by a presidential majority; the president has thus been able to set the policy agenda and implement his preferred policy.

- 1 2 Ayriyan, Serine (April 2016). "Armenia a gateway for Iranian goods?". ControlRisks | Russia/CIS Riskwatch Issue 9. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- 1 2 "Majority of Voters Support Armenia's Constitutional Reform". Sputnik. 7 December 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ↑ Sanamyan, Emil. "A1 Plus, ARFD Nominates Vahan Hovhannisyan". Open Democracy. Retrieved 2017-03-28.

- ↑ "A1 Plus, ARFD Nominates Vahan Hovhannisyan". Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ Horizon Armenian Weekly, English Supplement, 2007 3 December, page E1, "ARF conducts 'Primaries' ", a Yerkir agency report from Yerevan.

- ↑ http://www.atb.am/en/armenia/country/

- ↑ Global Corruption Report 2008, Transparency International, Chapter 7.4, p. 225.

- ↑ 2008 CORRUPTION PERCEPTIONS INDEX Archived 2009-03-11 at the Wayback Machine., Transparency International, 2008.

- ↑ Global Corruption Report 2008, Transparency International, Chapter 7, p. 122.

- ↑ "Strengthening Cooperation between the National Assembly, Civil Society and the Media in the Fight Against Corruption", Speech by Ms. Consuelo Vidal, (UN RC / UNDP RR), April 6, 2006.

External links

- Global Integrity Report: Armenia has information on anti-corruption efforts

- Petrosyan, David: "The Political System of Armenia: Form and Content" in the Caucasus Analytical Digest No. 17

- http://www.coc.am/LegislationEng.aspx

- http://www.coc.am/files/legislation/COCLawArm.pdf

- http://www.parliament.am