Ebensee concentration camp

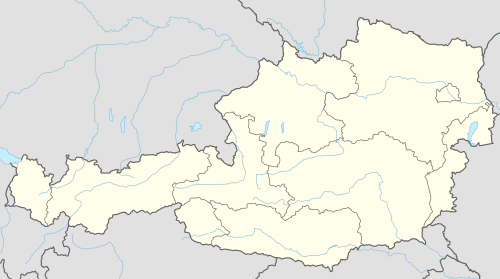

Coordinates: 47°47′15″N 13°45′28″E / 47.78750°N 13.75778°E

| Ebensee concentration camp | |

|---|---|

| Concentration camp | |

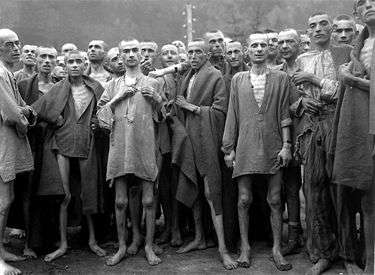

Ramshackle buildings surrounded by conifers and mountains Ebsensee Camp in 1945 | |

Location of Ebensee in Austria | |

| Other names | Kalk, Kalksteinbergwerk, Solvay, Zement |

| Operated by | DEST cartel and the Nazi Schutzstaffel (SS) |

| Commandant | Georg Bachmayer; Otto Riemer |

| Operational | November 1943 – May 1945 |

| Inmates | political prisoners from many countries |

| Number of inmates | about 27,000 |

| Killed | between 8,500 and 11,000 (estimated) |

| Liberated by | US Army, May 6, 1945 |

The Ebensee concentration camp was established by the SS to build tunnels for armaments storage near the town of Ebensee, Austria, in 1943. It was part of the Mauthausen network. The SS used several codenames: Kalk (English: limestone), Kalksteinbergwerk (English: limestone mine), Solvay and Zement (English: cement) to conceal the true nature of the camp.[1]

Formation

The construction of the Ebensee subcamp began late in 1943, and the first prisoners arrived on November 18, 1943, from the main camp of Mauthausen and its subcamps.[1] The main purpose of Ebensee was to provide slave labor for the construction of enormous underground tunnels in which armament works were to be housed, safe from bombing. These tunnels were planned for the evacuated Peenemünde V-2 rocket development but, on July 6, 1944, Hitler ordered the complex converted to a tank-gear factory.[2][3] One tunnel was used as a petroleum refinery.[4]

27,278 male inmates were sent to Ebensee.[1] Between 8,500 and 11,000 died in the camp.[4] Jews formed about one-third of the inmates. The other inmates were from Russia, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Yugoslavia, France, Italy, and Greece. Romani people were also imprisoned.[1] Most were political prisoners.[4] Mauthausen received the harshest classification of concentration camp after Heydrich decreed that they be classified in 1941. The mortality rate in camps in the Mauthausen group was three times higher than that of other groups.[5]:258

Georg Bachmayer oversaw construction. The Commandant Otto Riemer, and SS-Obersturmführer, oversaw the camp in 1944. His fate is unknown.[6]

Conditions

Prisoners arose at 4:30 a.m. and worked until 6:00 p.m., constructing and expanding the tunnels; some prisoners worked through the night. Piles of bodies were transported to the Mauthausen crematorium to be burned until Ebensee received its own crematorium. Prisoners wore wooden clogs or went barefoot. Lice infested the camp. Food rations consisted of coffee substitute for breakfast, hot water with potato peels for lunch; and a piece of bread for dinner.[6] One thousand five hundred and three Jewish prisoners were recorded in the Jewish sick room in the camp. Ninety-five percent died from "hunger and diseases resulting from malnutrition." [5]:266

In an oral history interview, camp survivor Max Moneta reported that the barracks were not heated and that meals were irregular. Sometimes prisoners received coffee for breakfast. There were no baths, and lice were common. Prisoners who worked the night shift were not allowed to sleep in the barracks during the day. Moneta said that fellow non-Jewish prisoners discriminated against Jewish prisoners. As allied forces closed in on Nazi territories, prisoners from other camps were sent to Ebensee, and there was not enough food to feed everyone.[7]

In June 1944, Jewish prisoners started to arrive. Beginning in 1945, thousands of prisoners from other concentration camps arrived in Ebensee. They were mostly Jewish.[4] On March 3, 1945, over 2,000 Jewish prisoners arrived from the Wolfsberg sub-camp of Gross-Rosen. Commander Anton Ganz forced them to remain outside during snowy weather for almost two days, and hundreds of prisoners died of the exhaustion of transport and exposure.[1] The following April, around 4,500 prisoners died. In May 1945, there were 18,500 inmates.[4] Barracks meant to hold 100 prisoners held over 700, and prisoners were also kept in tunnels and outdoors.[6]

Liberation

In May 1945, shooting in the distance could be heard from inside the camp and there was a sense among prisoners that American and British forces were close at hand. On May 4, 1945, the commandant of the camp informed prisoners that they had been sold to the Americans and that they should seek shelter in the camp's underground tunnels for protection. Prisoners refused and remained in their barracks; hours later some of the tunnels exploded, reputedly due to the detonation of mines. On May 5, 1945, prisoners awoke to find that the SS had deserted Ebensee and that only elderly Germans armed with rifles were guarding the camp.[7]

American troops of the US 80th Infantry Division arrived at the camp on May 6, 1945. Robert B. Persinger, a member of the platoon who liberated the camp, recalled that prisoners appeared to be starving and were barely clothed. A prisoner who spoke English, Max Garcia, showed the troops the stacks of bodies near the crematorium. After seeing the camp, American troops reported that 300 prisoners were dying of starvation every day. They requisitioned local food and made soup for the prisoners, but a few died from refeeding syndrome.[8][3] On May 7, lieutenant colonel Marshall Wallach and colonel James H. Polk visited the camp and ordered ration trucks to deliver food. U.S. Army Corps photographer J Malan Heslop took photographs that day.[3][9]

Holocaust survivor and author Moshe Ha-Elion recalls that when the camp was liberated, the Polish inmates were singing the Polish hymn, the Greek inmates were singing the Greek hymn[10] and the French inmates were singing La Marseillaise.[11] After, the Jews inmates were singing Ha Tikvah.[11]

Post-war commemoration

In the immediate aftermath of liberation, survivors set up a cemetery for prisoners who died in the camp outside of Ebensee. In 1952, the cemetery was relocated nearer to the former location of the concentration camp, and about 4,000 victims are buried there. In 1946 the residential homes were built on the site of the concentration camp. The Resistance Museum Ebensee Association created a memorial tunnel in 1994, where a display about the history of the camp existed since 1996. In 2001, Museum for Contemporary History Ebensee opened and includes an archive with photos and the names of the prisoners in the camp.[4] Stone steps have been carved in the Loewengang or Lion's Walk, where prisoners marched from the camp to the tunnels where they worked.[6] For many of the large satellite camps like Ebensee, memorialization is comparatively scant.[12]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "History of KZ Ebensee". Zeitgeschichte Museum und KZ-Gedenkstätte Ebensee. 2009-07-05. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06.

- ↑ Irving, David (1964). The Mare's Nest. London: William Kimber and Co. p. 238.

- 1 2 3 Nawyn, Kathleen J. "The Liberation of the Ebensee Concentration Camp, May 1945". history.army.mil. U.S. Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Information Portal to European Sites of Remembrance". www.memorialmuseums.org. Museum for Contemporary History and Ebensee Concentration Camp Memorial. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- 1 2 Eckstein, Benjamin (1984). "Jews in the Mauthausen Concentration Camp". In Gutman, Yisrael; Saf, Avital. The Nazi Concentration Camps: Proceedings of the Fourth Yad Veshem International Historic Conference January 1980. Jerusalem: Yad Veshem.

- 1 2 3 4 "Ebensee (Austria)". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- 1 2 Jonathan Moneta (26 February 2013). "Max Moneta - Holocaust Survivor Interview & Testimony" – via YouTube.

- ↑ Persinger, Robert B. "Remembering Ebensee 1945 Robert B. Persinger, May 6th 2005". Memorial Ebensee. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011.

- ↑ "J Malan Heslop". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ↑ "Moshé Haelion, el verbo del horror nazi llamado Auschwitz".

- 1 2 "Shalom - Moshe Haelion, Shalom - RTVE.es A la Carta". 1 May 2016.

- ↑ Wachsmann & Caplan, eds. (2010). Concentration Camps in Nazi Germany: The New Histories, p. 202.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ebensee concentration camp. |