Richard J. Daley

| Richard Daley | |

|---|---|

Daley, 1970. | |

| 38th Mayor of Chicago | |

|

In office April 20, 1955 – December 20, 1976 | |

| Preceded by | Martin H. Kennelly |

| Succeeded by | Michael Bilandic |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Richard Joseph Daley May 15, 1902 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died |

December 20, 1976 (aged 74) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Resting place | Holy Sepulchre Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | [1][2] |

| Children | 7, including Richard, John, and William |

| Relatives | Patrick R. Daley (grandson) |

| Education | DePaul University (LLB) |

Richard Joseph Daley (May 15, 1902 – December 20, 1976) was an American politician who served as the 38th Mayor of Chicago for a total of 21 years beginning on April 20, 1955, until his death on December 20, 1976. Daley was the chairman of the Cook County Democratic Central Committee for 23 years, holding both positions until his death in office in 1976. Daley was Chicago's third consecutive mayor from the working-class, heavily Irish American Bridgeport neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, where he lived his entire life. Daley is remembered for doing much to avoid the declines that some other "rust belt" cities—like Cleveland, Buffalo and Detroit—experienced during the same period. He had a strong base of support in Chicago's Irish Catholic community, and he was treated by national politicians such as Lyndon B. Johnson as a pre-eminent Irish American, with special connections to the Kennedy family. Daley played a major role in the history of the Democratic Party, especially with his support of John F. Kennedy in 1960 and of Hubert Humphrey in 1968. Daley is the father of Richard M. Daley, also a former mayor of Chicago, William M. Daley, a former United States Secretary of Commerce, and John P. Daley, a member of the Cook County Board of Commissioners. While many members of Daley's administration were charged with corruption and convicted, Daley himself was never charged with corruption.

Early life

Richard J. Daley was born in Bridgeport, a working-class neighborhood of Chicago.[3] He was the only child of Michael and Lillian (Dunne) Daley, whose families had both arrived from the Old Parish area, near Dungarvan, County Waterford, Ireland during the Great Famine.[4] Daley would later state that his wellsprings were his religion, his family, his neighborhood, the Democratic Party, and his love of the city.[4] His father was a sheet metal worker with a reserved demeanor. Michael's father, James E. Daley, was a butcher born in New York, while his mother, Delia Gallagher Daley, was an Irish immigrant. Richard's mother was outgoing and outspoken. Before women obtained the right to vote in 1920, Lillian Daley was an active Suffragette, participating in marches. Mrs. Daley often brought her son to them. She hoped her son's life would be more professionally successful than that of his parents. Prior to his mother's death, Daley had won the Democratic nomination for Cook County sheriff. Lillian Daley wanted more than this for her son, telling a friend, "I didn't raise my son to be a policeman."[5]

Education

Daley attended the elementary school of his parish, Nativity of Our Lord,[5] and De La Salle Institute (where he learned clerical skills) and took night classes at DePaul University College of Law to earn a Bachelor of Laws in 1933. As a young man, his jobs included selling newspapers and making deliveries for a door to door peddler; Daley worked in Chicago's Union stock yards (the conditions of which were made infamous in Upton Sinclair's novel The Jungle) to pay his law school expenses. He spent his free time at the Hamburg Athletic Club, an athletic, social and political organization near his home. Hamburg and similar clubs were funded, at least in part, by Democratic politicians. Daley made his mark there, not in sports, but in organization as the club manager. At age 22, he was elected president of the club and served in that office until 1939.[5] Although he practiced law with partner William J. Lynch, he dedicated the majority of his time to his political career.[6]

Political career

Early career

Daley's career in politics began when he became a Democratic precinct captain; although he was a lifelong Democrat, Daley was first elected to the Illinois House of Representatives as a Republican in 1936. This was a matter of political opportunism and the peculiar setup for legislative elections in Illinois at the time, which allowed Daley to take the place on the ballot of the recently deceased Republican candidate David Shanahan. After his election, Daley quickly moved back to the Democratic side of the aisle in 1938, when he was elected to the Illinois State Senate.[7] In 1939, Illinois State Senator William "Botchy" Connors remarked "You couldn't give that guy a nickel, that's how honest he is." Daley was appointed by Governor Adlai Stevenson as head of the Illinois Department of Finance. Daley suffered his only political defeat in 1946, when he lost a bid to become Cook County sheriff. Daley then made a successful run for Cook County Clerk and held that position prior to being elected Chicago's mayor.[6] In the late 1940s, Daley became Democratic Ward Committeeman of the 11th Ward, a post he retained until his death.

Daley became chairman of the Central Committee of the Cook County Democratic Party, i.e. "boss" of the "political machine" in 1953.[8] Holding this position along with the mayoralty in later years enhanced Daley's power.

First elected mayor in 1955, Daley beat Robert Merriam by 708,222 votes to 581,555. Daley was re-elected to that office five times and had been mayor for 21 years at the time of his death. Through those 21 years, the Illinois license plate on his car remained "708 222".[9] During his administration, Daley ruled the city with an iron hand and dominated the political arena of the city and, to a lesser extent, that of the entire state. Officially, Chicago has a "weak-mayor" system, in which most of the power is vested in the city council. However, his post as de facto leader of the Chicago Democratic Party gave him great influence over the city's ward organizations, which in turn allowed him a considerable voice in Democratic primary contests—in most cases, the real contest in this heavily Democratic city.

Daley met Eleanor "Sis" Guilfoyle at a local ball game. He courted "Sis" for six years, during which time he finished law school and was established in his legal profession. They were married on June 17, 1936, and lived in a modest brick bungalow at 3536 South Lowe Avenue in the heavily Irish-American neighborhood of Bridgeport, just blocks from his birthplace.[5] They had three daughters and four sons, in that order. Their eldest son, Richard M. Daley, was elected mayor of Chicago in 1989, and served in that position until his retirement in 2011. The youngest son, William M. Daley, served as White House Chief of Staff under President Barack Obama and as US Secretary of Commerce under President Bill Clinton. Another son, John P. Daley, is a member of the Cook County Board of Commissioners. The other progeny have stayed out of public life. Michael Daley is a partner in the law firm Daley & George, and Patricia (Daley) Martino and Mary Carol (Daley) Vanecko are teachers, as was Eleanor, who died in 1998.[10]

Major construction during his terms in office resulted in O'Hare International Airport, the Sears Tower, McCormick Place, the University of Illinois at Chicago, numerous expressways and subway construction projects, and other major Chicago landmarks.[11] O'Hare was a particular point of pride for Daley, with him and his staff regularly devising occasions to celebrate it. Daley also contributed to John F. Kennedy's narrow, 8,000 vote victory in Illinois in 1960[12] A PBS documentary entitled "Daley" explained that Mayor Daley and JFK potentially helped steal the 1960 election by stuffing ballot boxes and rigging the vote in Chicago. In 1966, SCLC's James Bevel and Martin Luther King Jr. took the Civil Rights Movement north and encouraged racial integration of Chicago's neighborhoods, such as Marquette Park.[13] Daley called for a "summit conference" and signed an agreement with King and other community leaders to foster open housing. The public agreement itself was without legal standing and ignored.[14] SCLC's efforts in Chicago contributed to the passage of the Fair Housing Act two years later.[15]

1968 and later career

The year 1968 was a momentous year for Daley. In April, Daley was castigated by many for his sharp rhetoric in the aftermath of rioting that took place after Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination. Displeased with what he saw as an over-cautious police response to the rioting, Daley chastised police superintendent James B. Conlisk and subsequently related that conversation at a City Hall press conference as follows:[16]

I said to him very emphatically and very definitely that an order be issued by him immediately to shoot to kill any arsonist or anyone with a Molotov cocktail in his hand, because they're potential murderers, and to shoot to maim or cripple anyone looting.

This statement generated significant controversy. Daley's supporters deluged his office with grateful letters and telegrams (nearly 4,500 according to Time magazine). But others were appalled. Reverend Jesse Jackson, for example, called it "a fascist's response." The Mayor later backed away from his words in an address to the City Council, saying:

"It is the established policy of the police department – fully supported by this administration – that only the minimum force necessary be used by policemen in carrying out their duties." Later that month, Daley asserted, "There wasn't any shoot-to-kill order. That was a fabrication."

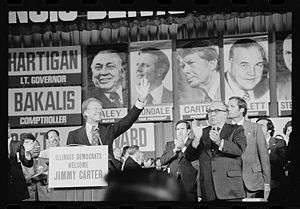

In August, the 1968 Democratic National Convention was held in Chicago. Intended to showcase Daley's achievements to national Democrats and the news media, the proceedings during the convention instead garnered notoriety for the mayor and city, descending into verbal outbursts on the part of politicians, and a circus for the media. With the nation divided by the Vietnam War and with the assassinations of King and Robert F. Kennedy earlier that year serving as backdrop, the city became a battleground for anti-Vietnam war protesters who vowed to shut down the convention. In some cases, confrontations between protesters and police turned violent, with images of this violence broadcast on national television. Later, anti-war activists Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, and three other members of the "Chicago Seven" were convicted of crossing state lines with the intent of inciting a riot as a result of these confrontations, though the convictions were overturned on appeal. At the convention itself, Sen. Abraham A. Ribicoff (D-Conn.), went off-script during his speech nominating George McGovern, saying, "And with George McGovern as President of the United States, we wouldn't have to have Gestapo tactics in the streets of Chicago. And with George McGovern as president, we wouldn't have to have a National guard." Ribicoff, with his voice shaking, then said: "How hard it is to speak the truth, when we know the problems that are facing this nation", for which some in the crowd booed Ribicoff. Ribicoff also tried to introduce a motion to shut down the convention and move it to another city. Many conventioneers applauded Ribicoff's remarks but an indignant Mayor Daley tried to shout down the speaker. As television cameras focused on Daley, lip-readers later said they observed him shouting, "Fuck you, you Jew son of a bitch, you lousy motherfucker go home."[17][18] Defenders of the mayor later stated that he was calling Ribicoff a faker,[19][20] a charge denied by Daley and refuted by Mike Royko's reporting.[21] A federal commission, led by local attorney, party activist Dan Walker, investigated the events surrounding the convention and described them as a "police riot." Daley defended his police force with the following statement, which was also a slip of the tongue: "The confrontation was not caused by the police. The confrontation was caused by those who charged the police. Gentlemen, let's get this thing straight, once and for all. The policeman is not here to create disorder. The policeman is here to preserve disorder."[22]

Public opinion polls conducted after the convention demonstrated that the majority of Americans supported the Mayor's tactics.[23] Daley was historically re-elected for the fifth time in 1971. However, many have argued this was due to a lack of formidable opposition rather than Daley's own popularity.[24] In 1972, Democratic nominee George McGovern threw Daley out of the Democratic National Convention, replacing his delegation with one led by Jesse Jackson. This event arguably marked a downturn in Daley's power and influence within the Democratic Party but, given his public standing, McGovern later made amends by putting Daley loyalist (and Kennedy in-law) Sargent Shriver on his ticket. In January 1973, former Illinois Racing Board Chairman William S. Miller testified that Daley had "induced" him to bribe Illinois Governor Otto Kerner.

Death and funeral

Shorty after 2:00 p.m. on December 20, 1976, Daley collapsed on the city's near-north side while on his way to lunch. Daley was rushed to the office of his private physician at 900 North Michigan Avenue. It was confirmed that he suffered a massive heart attack and Daley was pronounced dead at 2:55 p.m.; He was 74 years old.[25] Daley's funeral took place in the church he attended since his childhood, Nativity of Our Lord.[5] He is buried in Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Worth Township, southwest of Chicago. Daley was known by many Chicagoans as "Da Mare" ("The Mayor"), "Hizzoner" ("His Honor"), and "The Man on Five" (his office was on the fifth floor of City Hall). Since Daley's death and the subsequent election of son Richard as mayor in 1989, the first Mayor Daley has become known as "Boss Daley,"[26] "Old Man Daley," or "Daley Senior" to residents of Chicago.

Speaking style

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Richard J. Daley |

Daley, who never lost his blue-collar Chicago accent, was known for often mangling his syntax and other verbal gaffes. Daley made one of his most memorable verbal missteps in 1968, while defending what the news media reported as police misconduct during that year's violent Democratic Convention, stating, "Gentlemen, get the thing straight once and for all — the policeman isn't there to create disorder, the policeman is there to preserve disorder." Daley's reputation for misspeaking was such that his press secretary Earl Bush would tell reporters, "Write what he means, not what he says."[27]

Legacy

A poll of 160 historians, political scientists and urban experts ranked Daley as the sixth best mayor in American history.[28] On the 50th anniversary of Daley's first 1955 swearing-in, several dozen Daley biographers and associates met at the Chicago Historical Society. Historian Michael Beschloss called Daley "the pre-eminent mayor of the 20th century." Chicago journalist Elizabeth Taylor said, "Because of Mayor Daley, Chicago did not become a Detroit or a Cleveland." Robert Remini pointed out that while other cities were in fiscal crisis in the 1960s and 1970s, "Chicago always had a double-A bond rating." According to Chicago folksinger Steve Goodman, "no man could inspire more love, more hate." Daley's twenty-one-year tenure as mayor is memorialized in the following:

- A week after his death, the former William J. Bogan Junior College, one of the City Colleges of Chicago, was renamed as the Richard J. Daley College in his honor.

- The Richard J. Daley Center (originally, the Cook County Civic Center) is a 32-floor office building completed in 1965 and renamed for the mayor after his death.

- The Richard J. Daley Library, the primary academic library at the University of Illinois at Chicago [29]

- Richard J. Daley Bicentennial Park immediately east of Millennium Park and north of Grant Park

- The Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young song "Chicago" (written by Graham Nash) was about the 1968 Democratic convention. In their Four Way Street live album, Nash ironically dedicates the song to "Mayor Daley."

- The first verse Steve Goodman's original 1972 version of "The Lincoln Park Pirates" contains the line, "the stores are all closing and Daley is dozing". Following Daley's death, Goodman replaced the reference with "... and Bilandic's been chosen". Goodman also wrote and recorded a song called "Daley's Gone," which appeared on his 1977 album Say It in Private.

- Songwriters Tom Walsh, Tom Black and Terry McEldowney pay homage to Daley in "South Side Irish", making him the subject of the entire third verse.

- In episode 13 of the third season of Saturday Night Live, a sketch entitled "Miracle in Chicago" portrays Mayor Daley (played by John Belushi) appearing as a ghost to a pub owner and a customer (played respectively by Dan Aykroyd and Bill Murray). Daley has come back to give the new Mayor a few electoral tips and complain about his burial site. Before disappearing again, he helps the owner get the popular Irish song Too Ra Loo Ra Loo Ral on his juke box and leaves him a gift turkey.

- In a scene set at the Chez Paul restaurant in the 1980 film The Blues Brothers, the Maître d' (Alan Rubin) is seen talking on the phone: "No, sir, Mayor Daley no longer dines here, sir. He's dead, sir." Later in the film, when the brothers are driving rapidly through Chicago, Elwood (Dan Aykroyd) comments "If my estimations are correct, we should be very close to the Honorable Richard J. Daley Plaza." "That's where they got that Picasso!" Jake enthuses. The classic "use of unnecessary violence in the apprehension of the Blues Brothers has been approved" line delivered by a police dispatcher is an obvious homage to Daley's 1968 order during the riots following Martin Luther King's assassination.

See also

- Timeline of Chicago, 1950s–1970s

References

- ↑ "Eleanor "Sis" Daley". Chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ Cohen, Adam; Taylor, Elizabeth (8 May 2001). "American Pharaoh: Mayor Richard J. Daley - His Battle for Chicago and the Nation". Little, Brown. Retrieved 17 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Green, Paul Michael; Holli, Melvin G. (2005). The Mayors: the Chicago political tradition. Carbondale: SIU Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-8093-2612-9.

- 1 2 Cohen, Adam; Taylor, Elizabeth (2001). American pharaoh : Mayor Richard J. Daley ; his battle for Chicago and the nation. New York: Back Bay. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-316-83489-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cohen, Adam; Taylor, Elizabeth, eds. (2000). American Pharaoh: Mayor Richard J. Daley—His Battle for Chicago and the Nation. Little, Brown and Company. p. 624. ISBN 0-316-83403-3. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- 1 2 "Richard J. Daley". Cook County Clerk. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ↑ "Richard J. Daley". Political Graveyard.

- ↑ "Daley's Chicago". Encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ "Daley wins first election". Wbez.org. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ "Daley". Chicagobusiness.com. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ Cillizza, Chris (23 September 2009). "The Fix - Hall of Fame - The Case for Richard J. Daley". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Greenberg, David (16 October 2000). "Was Nixon Robbed?". Slate.com. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ "Randy Kryn: Movement Revision Research Summary Regarding James Bevel - Chicago Freedom Movement". cfm40.middlebury.edu. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ Royko, Mike Boss, Penguin Books (1971) p. 158.

- ↑ Kryn in Middlebury

- ↑ Perlstein, Rick (2008). Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-4302-5.

- ↑ Kusch, Frank (2008). Battleground Chicago: The Police and the 1968 Democratic National Convention. University of Chicago Press. p. 108. ISBN 9780226465036.

- ↑ Farber, David (1994). Chicago '68. University of Chicago Press. p. 249. ISBN 9780226237992.

- ↑ Marc, Schogol. "Views differ on impact of religious bias in race", Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, August 9, 2000. Accessed May 21, 2007. "Chicago Mayor Richard Daley cursed Ribicoff with an anti-Semitic slur at the raucous 1968 Democratic National Convention."

- ↑ Singh, Robert. "American Government and Politics: A Concise Introduction", Sage Publications (2003), p. 106. "Chicago police assaulted anti-war protesters, while inside turmoil engulfed proceedings and Chicago boss Richard Daley hurled anti-Semitic abuse at Senator Abraham Ribicoff (Democratic, Connecticut)."

- ↑ Royko, p. 189.

- ↑ Witcover, page 272

- ↑ Bogart, Leo. Polls and the Awareness of Public Opinion. Transaction Publishers. p. 235. ISBN 1412831504.

- ↑ Biles, Roger. Richard J. Daley: Politics, Race, and the Government of Chicago. Northern Illinois University Press (1995). p.183

- ↑ "Mayor Richard Daley of Chicago Dies at 74". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ↑ "Richard J. Daley American politician and lawyer". britannica.com. ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- ↑ Schmidt, William E (February 2, 1989). "Chicago Journal; Syntax Is a Loser in Mayoral Race". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-12.

- ↑ Holli, Melvin G. (1999). The American Mayor. University Park: PSU Press. ISBN 0-271-01876-3.

- ↑

Further reading

Biographies

- Cohen, Adam; Elizabeth Taylor (2000). American Pharaoh: Mayor Richard J. Daley: His Battle for Chicago and the Nation. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-83403-3. Detailed scholarly biography.

- Goodman, Barak (director) (1995). Daley: The Last Boss (documentary). Originally shown on the PBS program American Experience.

- Kennedy, Eugene (1978). Himself!: The Life and Times of Mayor Richard J. Daley. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-37258-7.

- O'Connor, Len (1975). Clout: Mayor Daley and His City. Chicago: H. Regnery. ISBN 0-8092-8291-7.

- Royko, Mike (1971). Boss: Richard J. Daley of Chicago. New York: Dutton. ISBN 0-525-07000-1.

- Witcover, Jules (1997). The Year the Dream Died: Revisiting 1968 in America. New York: Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-67471-0.

- O Gadhra, Nollaig (1979). Richard J. Daley, meara Chicago. Dublin: Foilseachain Naisiunta. This Irish-language biography of Richard Daley is considered to be one of the most thorough and comprehensive biographies ever written in Irish.

Academic studies

- Biles, Roger (1995). Richard J. Daley: Politics, Race, and the Government of Chicago. DeKalb, Ill.: Northern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-87580-199-4.

- Holli, Melvin G. (1999). The American Mayor: The Best and the Worst Big-city Leaders. University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01876-3. Charles Kolb, Review of The American Mayor.

- Peterson, Paul E. (1976). School Politics, Chicago Style. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-66288-8.

- Rakove, Milton L. (1975). Don't Make No Waves—Don't Back No Losers: An Insider's Analysis of the Daley Machine. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-11725-9.

- Simpson, Dick (2001). Rogues, Rebels, and Rubber Stamps: The Politics of the Chicago City Council from 1863 to the Present. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-9763-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Richard J. Daley. |

- Remembering Richard J. Daley - UIC Library

- Mayor Richard J. Daley

- Mayor Richard J. Daley of Chicago

- Richard J. Daley at Find a Grave

- Daley Family Tree (interactive graphic)

- Booknotes interview with Elizabeth Taylor on American Pharaoh: Mayor Richard J. Daley, July 23, 2000.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Martin H. Kennelly |

Mayor of Chicago April 20, 1955 – December 20, 1976 |

Succeeded by Michael A. Bilandic |