Equal Rights Amendment

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States of America |

|---|

|

|

Preamble and Articles of the Constitution |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

|

| Unratified Amendments |

| History |

| Full text of the Constitution and Amendments |

|

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) is a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution designed to guarantee equal legal rights for all American citizens regardless of sex; it seeks to end the legal distinctions between men and women in terms of divorce, property, employment, and other matters.[1] The ERA was originally written by Alice Paul and Crystal Eastman. The amendment was introduced in Congress for the first time in 1921 and has prompted conversations about the meaning of legal equality for women and men ever since.

In the early history of the Equal Rights Amendment, middle-class women were largely supportive, while those speaking for the working class were often opposed, pointing out that employed women needed special protections regarding working conditions and employment hours. With the rise of the women's movement in the United States during the 1960s, the ERA garnered increasing support, and, after being reintroduced by U.S. Representative Martha Griffiths (D-Michigan), in 1971, it was approved by the U.S. House of Representatives on October 12 of that year and on March 22, 1972, it was approved by the U.S. Senate, thus submitting the ERA to the state legislatures for ratification, as provided for in Article V of the U.S. Constitution.

Congress had originally set a ratification deadline of March 22, 1979, for the state legislatures to consider the ERA. Through 1977, the amendment received 35 of the necessary 38 state ratifications. With wide, bipartisan support (including that of both major political parties, both houses of Congress, and Presidents Nixon, Ford and Carter)[2] the ERA seemed destined for ratification until Phyllis Schlafly mobilized conservative women in opposition, arguing that the ERA would disadvantage housewives and cause women to be drafted into the military.[3]

Five state legislatures (Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, Tennessee, and South Dakota) voted to revoke their ERA ratifications. Four claim to have rescinded their ratifications before the original March 22, 1979 ratification deadline, while the South Dakota legislature did so by voting to sunset its ratification as of that original deadline. However, it remains a legal question as to whether a state can revoke its ratification of a federal constitutional amendment.

In 1978, Congress passed (by simple majorities in each house), and President Carter signed, a joint resolution with the intent of extending the ratification deadline to June 30, 1982. Because no additional state legislatures ratified the ERA between March 22, 1979 and June 30, 1982, the validity of that disputed extension was rendered academic.[4]

On March 22, 2017, the 45th anniversary of Congress' submission of the ERA to the nation's state lawmakers, the Nevada Legislature became the first to ratify the ERA after the expiration of both deadlines[5] with its adoption of Senate Joint Resolution No. 2 (designated as "POM-15" by the U.S. Senate and published verbatim in the Congressional Record of April 5, 2017, at pages S2361 and S2362).[6]

The Illinois General Assembly then ratified the ERA on May 30, 2018 with its adoption of Senate Joint Resolution Constitutional Amendment No. 4 (designated as "POM-299" by the U.S. Senate and likewise published verbatim in the Congressional Record of September 12, 2018, at page S6141).[7]

Text

Section 1. Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

Section 2. The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

Section 3. This amendment shall take effect two years after the date of ratification.[8][9]

Background

On September 25, 1921, the National Woman's Party announced plans to campaign for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution to guarantee women equal rights with men. The text of the proposed amendment read:

Section 1. No political, civil, or legal disabilities or inequalities on account of sex or on account of marriage, unless applying equally to both sexes, shall exist within the United States or any territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.[11]

Alice Paul, the head of the National Women's Party, believed that the Nineteenth Amendment would not be enough to ensure that men and women were treated equally regardless of sex. In 1923, she revised the proposed amendment to read:

Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.[12]

Paul named this version the Lucretia Mott Amendment, after a female abolitionist who fought for women's rights and attended the First Women's Rights Convention.[13]

In 1943, Alice Paul further revised the amendment to reflect the wording of the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments. This text became Section 1 of the version passed by Congress in 1972.[14]

As a result, in the 1940s, ERA opponents proposed an alternative, which provided that "no distinctions on the basis of sex shall be made except such as are reasonably justified by differences in physical structure, biological differences, or social function." It was quickly turned down by both pro and anti-ERA coalitions.[15]

Feminists split

Since the 1920s, the Equal Rights Amendment has been accompanied by discussion among feminists about the meaning of women's equality.[16] Alice Paul and her National Woman's Party asserted that women should be on equal terms with men in all regards, even if that means sacrificing benefits given to women through protective legislation, such as shorter work hours and no night work or heavy lifting.[17] Opponents of the amendment, such as the Women's Joint Congressional Committee, believed that the loss of these benefits to women would not be worth the supposed gain to them in equality. Although it now appears courts would indeed consider physical distinctions when applying the amendment, and determine whether a compelling government interest was met by sex-based government classifications, those discussing the amendment at the time had not yet seen the thoughtful Constitutional interpretations relating to civil rights and sex-based classifications that occurred years later. In 1924, The Forum hosted a debate between Doris Stevens and Alice Hamilton concerning the two perspectives on the proposed amendment.[18] Their debate reflected the wider tension in the developing feminist movement of the early 20th century between two approaches toward gender equality. One approach emphasized the common humanity of women and men, while the other stressed women's unique experiences and how they were different from men, seeking recognition for specific needs.[19] The opposition to the ERA was led by Mary Anderson and the Women's Bureau beginning in 1923. These feminists argued that legislation including mandated minimum wages, safety regulations, restricted daily and weekly hours, lunch breaks, and maternity provisions would be more beneficial to the majority of women who were forced to work out of economic necessity, not personal fulfillment.[20] The debate also drew from struggles between working class and professional women. Alice Hamilton, in her speech "Protection for Women Workers," said that the ERA would strip working women of the small protections they had achieved, leaving them powerless to further improve their condition in the future, or to attain necessary protections in the present.[21]

The National Woman's Party already had tested its approach in Wisconsin, where it won passage of the Wisconsin Equal Rights Law in 1921.[22][23] The party then took the ERA to Congress, where U.S. Senator Charles Curtis, a future Vice President of the United States, introduced it for the first time in October 1921.[11] Although the ERA was introduced in every congressional session between 1921 and 1972, it almost never reached the floor of either the Senate or the House for a vote. Instead, it was usually blocked in committee; except in 1946, when it was defeated in the Senate by a vote of 38 to 35 — not receiving the required two-thirds supermajority.

Hayden rider and protective labor legislation

In 1950 and 1953, the ERA was passed by the Senate with a provision known as "the Hayden rider", introduced by Arizona Senator Carl Hayden. The Hayden rider added a sentence to the ERA to keep special protections for women: "The provisions of this article shall not be construed to impair any rights, benefits, or exemptions now or hereafter conferred by law upon persons of the female sex." By allowing women to keep their existing and future special protections, it was expected that the ERA would be more appealing to its opponents. Though opponents were marginally more in favor of the ERA with the Hayden rider, supporters of the original ERA believed it negated the amendment's original purpose—causing the amendment not to be passed in the House.[24][25][26]

ERA supporters were hopeful that the second term of President Dwight Eisenhower would advance their agenda. Eisenhower had publicly promised to "assure women everywhere in our land equality of rights," and in 1958, Eisenhower asked a joint session of Congress to pass the Equal Rights Amendment, the first president to show such a level of support for the amendment. However, the National Woman's Party found the amendment to be unacceptable and asked it to be withdrawn whenever the Hayden rider was added to the ERA.[26]

The Republican Party included support of the ERA in its platform beginning in 1940, renewing the plank every four years until 1980.[27] The ERA was strongly opposed by the American Federation of Labor and other labor unions, which feared the amendment would invalidate protective labor legislation for women. Eleanor Roosevelt and most New Dealers also opposed the ERA. They felt that ERA was designed for middle class women, but that working class women needed government protection. They also feared that the ERA would undercut the male-dominated labor unions that were a core component of the New Deal coalition. Most northern Democrats, who aligned themselves with the anti-ERA labor unions, opposed the amendment.[27] The ERA was supported by southern Democrats and almost all Republicans.[27]

At the 1944 Democratic National Convention, the Democrats made the divisive step of including the ERA in their platform, but the Democratic Party did not become united in favor of the amendment until congressional passage in 1972.[27] The main support base for the ERA until the late 1960s was among middle class Republican women. The League of Women Voters, formerly the National American Woman Suffrage Association, opposed the Equal Rights Amendment until 1972, fearing the loss of protective labor legislation.

1960s

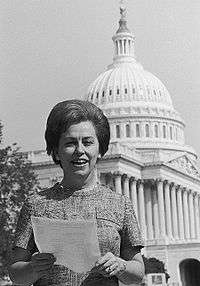

.jpg)

At the Democratic National Convention in 1960, a proposal to endorse the ERA was rejected after it met explicit opposition from liberal groups including the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the AFL–CIO, labor unions such as the American Federation of Teachers, Americans for Democratic Action (ADA), the American Nurses Association, the Women's Division of the Methodist Church, and the National Councils of Jewish, Catholic, and Negro Women.[28] The losing side then demanded that presidential candidate John F. Kennedy announce his support of the ERA; he did so in an October 21, 1960, letter to the chairman of the National Woman's Party.[29] When Kennedy was elected, he made Esther Peterson the highest-ranking woman in his administration as an Assistant Secretary of Labor. Peterson publicly opposed the Equal Rights Amendment based on her belief that it would weaken protective labor legislation.[30] Peterson referred to the National Woman's Party members, most of them veteran suffragists and preferred the "specific bills for specific ills" approach to equal rights.[30] Ultimately, Kennedy's ties to labor unions meant that he and his administration did not support the ERA.[31]

As a concession to feminists, Kennedy appointed a blue-ribbon commission on women, the President's Commission on the Status of Women, to investigate the problem of sex discrimination in the United States. The commission was chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt who opposed the ERA but no longer spoke against it publicly. In the early 1960s, Eleanor Roosevelt announced that, due to unionization, she believed the ERA was no longer a threat to women as it once may have been and told supporters that, as far as she was concerned, they could have the amendment if they wanted it. However, she never went so far as to endorse the ERA. The commission that she chaired reported (after her death) that no ERA was needed.[32] The commission did, though, help win passage of the Equal Pay Act of 1963 which banned sex discrimination in wages in a number of professions (it would later be amended in the early 1970s to include the professions that it initially excluded) and secured an executive order from Kennedy eliminating sex discrimination in the civil service. The commission, composed largely of anti-ERA feminists with ties to labor, proposed remedies to the widespread sex discrimination it unearthed and in its 1963 final report held that on the issue of equality "a constitutional amendment need not now be sought".[33]

The national commission spurred the establishment of state and local commissions on the status of women and arranged for follow-up conferences in the years to come. The following year, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 banned workplace discrimination not only on the basis of race, religion, and national origin, but also on the basis of sex, thanks to the lobbying of Alice Paul and Coretta Scott King and the skillful politicking of Representative Martha Griffiths of Michigan.

A new women's movement gained ground in the later 1960s as a result of a variety of factors: Betty Friedan's bestseller The Feminine Mystique; the network of women's rights commissions formed by Kennedy's national commission; the frustration over women's social and economic status; and anger over the lack of government and Equal Employment Opportunity Commission enforcement of the Equal Pay Act and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. In June 1966, at the Third National Conference on the Status of Women in Washington, D.C., Betty Friedan and a group of activists frustrated with the lack of government action in enforcing Title VII of the Civil Rights Act formed the National Organization for Women to act as an "NAACP for women", demanding full equality for American women and men. In 1967, at the urging of Alice Paul, NOW endorsed the Equal Rights Amendment. The decision caused some union Democrats and social conservatives to leave the organization and form the Women's Equity Action League (within a few years WEAL also endorsed the ERA), but the move to support the amendment benefited NOW, bolstering its membership. By the late 1960s, NOW had made significant political and legislative victories and was gaining enough power to become a major lobbying force. In 1969, newly-elected Representative Shirley Chisholm of New York gave her famous speech "Equal Rights for Women" on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Congressional passage

In February 1970, NOW picketed the United States Senate, a subcommittee of which was holding hearings on a constitutional amendment to lower the voting age to 18. NOW disrupted the hearings and demanded a hearing on the Equal Rights Amendment and won a meeting with Senators to discuss the ERA. That August, over 20,000 American women held a nationwide Women's Strike for Equality protest to demand full social, economic, and political equality.[34] Said Betty Friedan of the strike, "All kinds of women's groups all over the country will be using this week on August 26 particularly, to point out those areas in women's life which are still not addressed. For example, a question of equality before the law; we are interested in the Equal Rights Amendment." Despite being centered in New York City—which was regarded as one of the biggest strongholds for NOW and other groups sympathetic to the women's liberation movement such as Redstockings[35]—and having a small number of participants in contrast to the large-scale anti-war and civil rights protests that had occurred in the recent time prior to the event,[34] the strike was credited as one of the biggest turning points in the rise of second-wave feminism.[35]

In Washington, D.C., protesters presented a sympathetic Senate leadership with a petition for the Equal Rights Amendment at the U.S. Capitol. Influential news sources such as Time also supported the cause of the protestors.[34] Soon after the strike took place, activists distributed literature across the country as well.[35] In 1970, congressional hearings began on the ERA.

On August 10, 1970, Michigan Democrat Martha Griffiths successfully brought the Equal Rights Amendment to the House Floor, after fifteen years of the joint resolution languishing in the House Judiciary Committee. The joint resolution passed in the House and continued on to the Senate, which voted for the ERA with an added clause that women would be exempt from the military. The 91st Congress, however, ended before the joint resolution could progress any further.[36]

Griffiths reintroduced the ERA, and achieved success on Capitol Hill with her House Joint Resolution No. 208, which was adopted by the House on October 12, 1971, with a vote of 354 yeas (For), 24 nays (Against) and 51 not voting.[37] Griffiths' joint resolution was then adopted by the Senate—without change—on March 22, 1972, by a vote of 84 yeas, 8 nays and 7 not voting.[38] The Senate version, drafted by Senator Birch Bayh of Indiana,[39] passed after the defeat of an amendment proposed by Senator Sam Ervin of North Carolina that would have exempted women from the draft.[27] President Richard Nixon immediately endorsed the ERA's approval upon its passage by the 92nd Congress.[27]

Actions in the state legislatures

Ratifications

On March 22, 1972, the ERA was placed before the state legislatures, with a seven-year deadline to acquire ratification by three-fourths (38) of the state legislatures. Most states were eager to ratify the proposed constitutional amendment. The U.S. Senate's vote on House Joint Resolution No. 208 took place in the mid-to-late afternoon in Washington D.C., when it was still midday in Hawaii. The Hawaii Senate and House of Representatives voted their approval shortly after noon Hawaii Standard Time, making Hawaii the first state to ratify the ERA.[40]

During 1972, a total of 22 state legislatures ratified the amendment and eight more joined in 1973. Between 1974 and 1977, only five states approved the ERA, and advocates became worried about the approaching March 22, 1979 deadline.[41] At the same time, the legislatures of four states which had ratified the ERA then adopted legislation purporting to rescind those ratifications. If, indeed, a state legislature has the ability to rescind, then the ERA actually had ratifications by only 31 states – not 35 – when March 22, 1979, arrived.

The ERA has been ratified by the following states:[42]

- Hawaii (March 22, 1972)

- New Hampshire (March 23, 1972)

- Delaware (March 23, 1972)

- Iowa (March 24, 1972)

- Idaho (March 24, 1972)

- Kansas (March 28, 1972)

- Nebraska (March 29, 1972)

- Texas (March 30, 1972)

- Tennessee (April 4, 1972)

- Alaska (April 5, 1972)

- Rhode Island (April 14, 1972)

- New Jersey (April 17, 1972)

- Colorado (April 21, 1972)

- West Virginia (April 22, 1972)

- Wisconsin (April 26, 1972)

- New York (May 18, 1972)

- Michigan (May 22, 1972)

- Maryland (May 26, 1972)

- Massachusetts (June 21, 1972)

- Kentucky (June 26, 1972)

- Pennsylvania (September 27, 1972)

- California (November 13, 1972)

- Wyoming (January 26, 1973)

- South Dakota (February 5, 1973)

- Oregon (February 8, 1973)[43]

- Minnesota (February 8, 1973)

- New Mexico (February 28, 1973)

- Vermont (March 1, 1973)

- Connecticut (March 15, 1973)

- Washington (March 22, 1973)

- Maine (January 18, 1974)

- Montana (January 25, 1974)

- Ohio (February 7, 1974)

- North Dakota (March 19, 1975)

- Indiana (January 18, 1977)[44]

- Nevada (March 22, 2017)[45]

- Illinois (May 30, 2018)[46]

Ratifications rescinded

Although Article V is silent as to whether a state may rescind a previous ratification of a proposed—but not yet ratified—amendment to the U.S. Constitution,[47] legislators in the following four states nevertheless voted to retract their earlier ratification of the ERA:[48]

- Nebraska (March 15, 1973 – Legislative Resolution No. 9)

- Tennessee (April 23, 1974 – Senate Joint Resolution No. 29)

- Idaho (February 8, 1977 – House Concurrent Resolution No. 10)

- Kentucky (March 17, 1978 – House (Joint) Resolution No. 20)

The Lieutenant Governor of Kentucky, Thelma Stovall, who was acting as governor in the governor's absence, "vetoed" the rescinding resolution—[49] raising questions as to whether a state's governor, or someone temporarily acting as governor, has the power to veto any measure relative to amending the United States Constitution. (Refer to "Executive branch involvement in ratification process" below).

Ratifying state with self-declared March 22, 1979 sunset provision

The action of the 95th Congress in October 1978 to extend the ERA ratification deadline from March 22, 1979, to June 30, 1982, was not universally accepted. On December 23, 1981, a federal district court ruled in Idaho v. Freeman that Congress had no power to extend ERA's ratification deadline. On January 25, 1982, the U.S. Supreme Court opted to stay the district court's decision. Taking no further action on the matter until October 4, 1982, the High Court, on that date, ruled in NOW v. Idaho and Carmen v. Idaho that the controversy had been rendered moot by virtue of the fact that no additional state legislatures ratified ERA between March 22, 1979 and June 30, 1982.[50]

Among those rejecting Congress's claim to even hold such authority, the South Dakota Legislature adopted Senate Joint Resolution No. 2 on March 1, 1979. The joint resolution stipulated that South Dakota's 1973 ERA ratification would be "sunsetted" as of the original March 22, 1979 deadline. South Dakota's 1979 sunset joint resolution declared: "...the Ninety-fifth Congress ex post facto has sought unilaterally to alter the terms and conditions in such a way as to materially affect the congressionally established time period for ratification..." (designated as "POM-93" by the U.S. Senate and published verbatim in the Congressional Record of March 13, 1979, at pages 4861 and 4862).[51]

The action on the part of South Dakota lawmakers—occurring 21 days prior to originally agreed-upon March 22, 1979 deadline—could be viewed as slightly different from a rescission. As noted in The Constitution of the United States Analysis and Interpretation (Centennial edition, 2017, at page 1005): "Four states had rescinded their ratifications [of the ERA] and a fifth had declared that its ratification would be void unless the [Equal Rights] amendment was ratified within the original time limit"; (see footnote 43 at the bottom of page 1005, which identifies South Dakota as that "fifth" state).[52][53]

Executive branch involvement in ratification process

The Constitution is silent as to whether the governor—or acting governor—of a state has any formal role to play regarding state ratification of an amendment to the Constitution. However, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Hollingsworth v. Virginia (1798)[54] that the President of the United States has no formal role in that process.

Non-ratifying states with one-house approval

At various times, in 7 of the 13 non-ratifying states, one house of the legislature approved the ERA. It failed in those states because both houses of a state's legislature must approve, during the same session, in order for that state to be deemed to have ratified.

- Florida – whose House of Representatives voted to ratify the ERA on March 24, 1972, with a tally of 91 to 4; a second time on April 10, 1975, with a tally of 62 to 58; a third time on May 17, 1979, with a tally of 66 to 53; and a fourth time on June 21, 1982, with a tally of 60 to 58.[55]

- Louisiana – whose Senate voted to ratify the ERA on June 7, 1972, with a tally of 25 to 13.

- Missouri – whose House of Representatives voted to ratify the ERA on February 7, 1975, with a tally of 82 to 75.[56]

- North Carolina – whose House of Representatives voted to ratify the ERA on February 9, 1977, with a tally of 61 to 55.[57]

- Oklahoma – whose Senate voted to ratify the ERA on March 23, 1972, by a voice vote.[58]

- South Carolina – whose House of Representatives voted to ratify the ERA on March 22, 1972, with a tally of 83 to zero.

- Virginia – whose Senate voted to ratify the ERA on February 7, 2011, with a tally of 24 to 16 (Senate Joint Resolution No. 357); a second time on February 14, 2012, with a tally of 24 to 15 (Senate Joint Resolution No. 130); a third time on February 5, 2014, with a tally of 25 to 8 (Senate Joint Resolution No. 78); a fourth time on February 5, 2015, with a tally of 20 to 19 (Senate Joint Resolution No. 216);[59] and a fifth time on January 26, 2016, with a tally of 21 to 19 (Senate Joint Resolution No. 1).[60]

Ratification resolutions have also been defeated in Arizona, Arkansas,[61] and Mississippi.[62][63][64]

Congressional extension of ratification deadline

The original joint resolution (H. J. Res. 208), by which the 92nd Congress proposed the amendment to the states, was prefaced by the following resolving clause:

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled (two-thirds of each House concurring therein), That the following article is proposed as an amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which shall be valid to all intents and purposes as part of the Constitution when ratified by the legislatures of three-fourths of the several States within seven years from the date of its submission by the Congress: [emphasis added]

As the joint resolution was passed on March 22, 1972, this effectively set a March 22, 1979 deadline for the amendment to be ratified by the requisite number of states. However, the 92nd Congress did not incorporate any time limit into the body of the actual text of the proposed amendment, as had been done with a number of other proposed amendments.[65]

In 1978, as the original 1979 deadline approached, the 95th Congress adopted House Joint Resolution No. 638 (H. J. Res. 638), by Representative Elizabeth Holtzman of New York, which purported to extend the ERA's ratification deadline to June 30, 1982.[66] H. J. Res. 638 received less than two-thirds of the vote (a simple majority, not a supermajority) in both the House of Representatives and the Senate; for that reason, ERA supporters deemed it necessary that H. J. Res. 638 be transmitted to then-President Jimmy Carter for signature as a safety precaution. Carter signed the joint resolution, although he noted, on strictly procedural grounds, the irregularity of his doing so.[67] During this disputed extension of slightly more than three years, no additional states ratified or rescinded.

_Ratification%2C_10-20-1978.jpg)

The purported extension of ERA's ratification deadline was vigorously contested in 1978 as scholars were divided as to whether Congress actually has authority to revise a previously agreed-to deadline for the states to act upon a Federal constitutional amendment. On June 18, 1980, a resolution in the Illinois House of Representatives resulted in a vote of 102-71 in favor, but Illinois' internal parliamentary rules required a three-fifths majority on constitutional amendments and so the measure failed by five votes. In 1982, seven female ERA supporters went on a fast and seventeen chained themselves to the entrance of the Illinois Senate chamber.[68][69][70] The closest that the ERA came to gaining an additional ratification between the original deadline of March 22, 1979 and the revised June 30, 1982, expiration date was when it was approved by the Florida House of Representatives on June 21, 1982. In the final week before the revised deadline, that ratifying resolution, however, was defeated in the Florida Senate by a vote of 16 yeas and 22 nays. Even if Florida had ratified the ERA, the proposed amendment would still have fallen short of the required 38.

According to research by Professor Jules B. Gerard, professor of law at Washington University in St. Louis, of the 35 legislatures that passed ratification resolutions, 24 of them explicitly referred to the original 1979 deadline.[71]

In the courts/Legal officials

On December 23, 1981, a federal district court, in the case of Idaho v. Freeman, ruled that the extension of the ERA ratification deadline to June 30, 1982, was not valid and that, ERA had actually expired from state legislative consideration more than two years earlier on the original expiration date of March 22, 1979. On January 25, 1982, however, the U.S. Supreme Court "stayed" the lower court's decision, thus signaling to the legislatures of still-unratified states that they may continue consideration of ERA during their spring 1982 legislative sessions.

After the disputed June 30, 1982, extended deadline had come and gone, the Supreme Court, at the beginning of its new term, on October 4, 1982, in the separate case of NOW v. Idaho, 459 U.S. 809 (1982), vacated the federal district court decision in Idaho v. Freeman,[72] which, in addition to declaring March 22, 1979, as ERA's expiration date, had upheld the validity of state rescissions. The Supreme Court declared these controversies moot on the grounds that the ERA had not received the required number of ratifications (38), so that "the Amendment has failed of adoption no matter what the resolution of the legal issues presented here."[73][74]

In the 1939 case of Coleman v. Miller,[75] the Supreme Court ruled that Congress has the final authority to determine whether, by lapse of time, a proposed constitutional amendment has lost its vitality before being ratified by enough states, and whether state ratifications are effective in light of attempts at subsequent withdrawal. The Court stated: "We think that, in accordance with this historic precedent, the question of the efficacy of ratifications by state legislatures, in the light of previous rejection or attempted withdrawal, should be regarded as a political question pertaining to the political departments, with the ultimate authority in the Congress in the exercise of its control over the promulgation of the adoption of the amendment."[76] The Court, in 1939, upheld Congressional authority to determine in 1868 that the Fourteenth Amendment was properly ratified, including states that had attempted to rescind prior ratifications.

In the context of this judicial precedent, nonpartisan counsel to a Nevada state legislative committee concluded in 2017 that "If three more states sent their ratification to the appropriate federal official, it would then be up to Congress to determine whether a sufficient number of states have ratified the Equal Rights Amendment."[77]

Similarly, an informal advisory provided to Virginia State Senator Scott A. Surovell from the Virginia Attorney General’s office stated that Congress has the power to extend the ratification deadline even further. The advisory also stated that even without such a further extension, a contemporary ratification of the ERA by the Virginia General Assembly could be found valid by Congress.[78]

In March, 2018, a formal opinion letter of Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring concurred, stating:[79]

"In light of Congress's significant control over the amendment process, I cannot conclude that it lacks the power to extend the period in which an amendment can be ratified and recognize a State's intervening ratifying resolution as legally effective for purposes of determining whether the ERA has been ratified. Although the precise issue you raise has not been conclusively resolved, the historical evidence and case law demonstrate Congress's significant, even plenary, power over the amending process."

The Attorney General added, citing extensive sources: "As recognized by the constitutional scholars who testified before Congress and in the report of the House Judiciary Committee recommending extension, the limited Supreme Court precedent in this area suggests that Congress has authority to extend a ratification deadline."[76]

After thorough discussion of legal precedent and testimony at the Congressional hearings, the opinion letter concluded: "It is my opinion that the lapse of the ERA's original and extended ratification periods has not disempowered the [Virginia] General Assembly from passing a ratifying resolution. Given Congress's substantial power over the amending process, I cannot conclude that Congress would be powerless to extend or remove the ERA's ratification deadline and recognize as valid a State's intervening act of ratification. Indeed, legislation currently pending in Congress seeks to exercise that very power."[80]

Support for the ERA

Supporters of the ERA point to the lack of a specific guarantee in the Constitution for equal rights protections on the basis of sex.[81] In 1973, future Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg summarized a supporting argument for the ERA in the American Bar Association Journal:

The equal rights amendment, in sum, would dedicate the nation to a new view of the rights and responsibilities of men and women. It firmly rejects sharp legislative lines between the sexes as constitutionally tolerable. Instead, it looks toward a legal system in which each person will be judged on the basis of individual merit and not on the basis of an unalterable trait of birth that bears no necessary relationship to need or ability.[82]

In the early 1940s both the Democratic and Republican parties added support for the ERA to their platforms.[83]

The National Organization for Women (NOW) and ERAmerica, a coalition of almost 80 organizations, led the pro-ERA efforts. Between 1972 and 1982, ERA supporters held rallies, petitioned, picketed, went on hunger strikes, and performed acts of civil disobedience.[41] On July 9, 1978, NOW and other organizations hosted a national march in Washington D.C., which garnered over 100,000 supporters, and was followed by a Lobby Day on July 10.[84] On June 6, 1982, NOW sponsored marches in states that had not passed the ERA including Florida, Illinois, North Carolina, and Oklahoma.[85] Key feminists of the time, such as Gloria Steinem, spoke out in favor of the ERA, arguing that ERA opposition was based on gender myths that overemphasized difference and ignored evidence of unequal treatment between men and women.[86]

Support for the ERA among people of color

Many women in the African American community have supported the ERA in light of the dual effects of both race and sex discrimination.[87] One prominent female supporter was New York Representative Shirley Chisholm. On August 10, 1970, she gave a speech on the ERA called "For the Equal Rights Amendment" in Washington D.C. In her address, she pointed out how widespread sex discrimination had become and how the ERA would remedy it. She also said that laws to protect women in the workforce from unsafe working conditions would be needed by men, too, and thus the ERA would help all people.[88]

By 1976, 60% of African American women and 63% of African American men were in favor of the ERA, and the legislation was supported by organizations such as the NAACP, National Council of Negro Women, Coalition of Black Trade Unionists, National Association of Negro Business, and the National Black Feminist Organization.[87]

Opposition to the ERA

Opponents of the ERA focused on traditional gender roles, such as how men do the fighting in wartime. They argued that the amendment would guarantee the possibility that women would be subject to conscription and be required to have military combat roles in future wars if it were passed. Defense of traditional gender roles proved to be a useful tactic. In Illinois, supporters of Phyllis Schlafly, a conservative Republican activist from that state, used traditional symbols of the American housewife. They took homemade bread, jams, and apple pies to the state legislators, with the slogans, "Preserve us from a congressional jam; Vote against the ERA sham" and "I am for Mom and apple pie."[89] They appealed to married women by stressing that the amendment would invalidate protective laws such as alimony and eliminate the tendency for mothers to obtain custody over their children in divorce cases.[90] It was suggested that single-sex bathrooms would be eliminated and same-sex couples would be able to get married if the amendment were passed.[3] Women who supported traditional gender roles started to oppose the ERA.[91] Schlafly said the ERA was designed for the benefit of young career women and warned that if men and women had to be treated identically it would threaten the security of middle-aged housewives with no job skills. They could no longer count on alimony or Social Security.[3] Opponents also argued that men and women were already equal enough with the passage of the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964,[92] and that women's colleges would have to admit men. Schlafly's argument that protective laws would be lost resonated with working-class women.[93]

At the 1980 Republican National Convention, the Republican Party platform was amended to end its support for the ERA.[95] The most prominent opponent of the ERA was Schlafly. Leading the Stop ERA campaign, Schlafly defended traditional gender roles and would often attempt to incite feminists by opening her speeches with lines such as, "I'd like to thank my husband for letting me be here tonight – I always like to say that, because it makes the libs so mad."[96] When Schlafly began her campaign in 1972, public polls showed support for the amendment was widely popular and thirty states had ratified the amendment by 1973. After 1973, the number of ratifying states slowed to a trickle. Support in the states that had not ratified fell below 50%.[97] Critchlow and Stachecki noted that public opinion in key states shifted against the ERA as opponents, operating on the local and state levels, won over the public. The state legislators in battleground states followed public opinion in rejecting the ERA.

Experts agree that Phyllis Schlafly was a key player in the defeat. Political scientist Jane Mansbridge in her history of the ERA argues that the draft issue was the single most powerful argument used by Schlafly and the other opponents to defeat ERA.[98] Mansbridge concluded, "Many people who followed the struggle over the ERA believed – rightly in my view – that the Amendment would have been ratified by 1975 or 1976 had it not been for Phyllis Schlafly's early and effective effort to organize potential opponents."[99] Legal scholar Joan C. Williams maintained, "ERA was defeated when Schlafly turned it into a war among women over gender roles."[100] Historian Judith Glazer-Raymo asserted:

As moderates, we thought we represented the forces of reason and goodwill but failed to take seriously the power of the family values argument and the single-mindedness of Schlafly and her followers. The ERA's defeat seriously damaged the women's movement, destroying its momentum and its potential to foment social change....Eventually, this resulted in feminist dissatisfaction with the Republican Party, giving the Democrats a new source of strength that when combined with overwhelming minority support, helped elect Bill Clinton to the presidency in 1992 and again in 1996.[101]

Many ERA supporters blamed their defeat on special interest forces, especially the insurance industry and conservative organizations, suggesting that they had funded an opposition that subverted the democratic process and the will of the pro-ERA majority.[102] Such supporters argued that while the public face of the anti-ERA movement was Phyllis Schlafly and her STOP ERA organization, there were other important groups in the opposition as well, such as the powerful National Council of Catholic Women, labor feminists and (until 1973) the AFL–CIO. Opposition to the amendment was particularly high among religious conservatives, who argued that the amendment would guarantee universal abortion rights and the right for homosexual couples to marry.[103][104] Critchlow and Stachecki say the anti-ERA movement was based on strong backing among Southern whites, Evangelical Christians, Mormons, Orthodox Jews, and Roman Catholics, including both men and women.[105] Sonia Johnson, a traditionally-raised Mormon housewife whose eventual feminist advocacy for the ERA's passage led to her excommunication by the LDS church, subsequently wrote about her experiences in the memoir From Housewife to Heretic. Johnson and others led a hunger strike/fast at the Illinois State Senate chamber in an unsuccessful effort to push the Illinois General Assembly toward ERA ratification before the 1982 revised deadline.

Post-deadline ratifications

Beginning in the mid 1990s, ERA supporters began an effort to win ratification of the ERA by the legislatures of states that did not ratify it between 1972 and 1982. These proponents state that Congress can remove the ERA's ratification deadline despite the deadline having expired, allowing the states again to ratify it. They also state that the ratifications ERA previously received remain in force and that rescissions of prior ratifications are not valid.[106] Those who espouse the "three-state strategy" (now down to only one state if the Nevada Legislature's and the Illinois General Assembly's belated ERA approvals are deemed legitimate) were spurred, at least in part, by the unconventional 202-year-long ratification of the Constitution's Twenty-seventh Amendment (sometimes referred to as the "Madison Amendment") which became part of the Constitution in 1992 after pending before the state legislatures since 1789. Although the "Madison Amendment" was not associated with a ratification deadline, whereas the proposing clause of the ERA did include a deadline, states have in the past ratified amendments after a deadline, and Congress has not rejected those ratifications (as the Supreme Court has said, "Congress in controlling the promulgation of the adoption of a constitutional amendment has the final determination of the question whether by lapse of time its proposal of the amendment had lost its vitality prior to the required ratifications").[107]

On June 21, 2009, the National Organization for Women decided to support both efforts to obtain additional state ratifications for the 1972 ERA and any strategy to submit a fresh-start ERA to the states for ratification.[108]

In 2013, the Library of Congress's Congressional Research Service issued a report saying that ratification deadlines are a political question:

ERA proponents claim that the Supreme Court's decision in Coleman v. Miller gives Congress wide discretion in setting conditions for the ratification process.

The report goes on to say:

Revivification opponents caution ERA supporters against an overly broad interpretation of Coleman v. Miller, which, they argue, may have been be [sic] a politically influenced decision.[109]

However, most recently, ERA Action has both led and brought renewed vigor to the movement by instituting what has become known as the "three state strategy".[110] It was in 2013 that ERA Action began to gain traction with this strategy through their coordination with U.S. Senators and Representatives not only to introduce legislation in both houses of Congress to remove the ratification deadline, but also in gaining legislative sponsors. The Congressional Research Service then issued a report on the "three state strategy" on April 8, 2013 entitled "The Proposed Equal Rights Amendment: Contemporary Ratification Issues",[111] stating that the approach was viable.

In 2014, under the auspices of ERA Action and their coalition partners, both the Virginia and Illinois state senates voted to ratify the ERA. That year, votes were blocked in both states' House chambers. In the meantime, the ERA ratification movement continued with the resolution being introduced in 10 state legislatures.[112][113][114]

On March 22, 2017, the Nevada Legislature became the first state in 40 years to ratify the ERA.[115]

Illinois lawmakers and citizens took another look at the ERA, with hearings, testimony, and research including work by the law firm Winston & Strawn to address common legal questions about the ERA.[116]

Illinois state lawmakers ratified the ERA on May 30, 2018, with a 72-45 vote in the Illinois House following a 43-12 vote in the Illinois Senate in April, 2018.[117][118]

On February 10, 2018, the final day of that year's legislative session on which the Virginia General Assembly committees could have brought up the four ERA resolutions for consideration, women and men from the League of Women Voters, Liberal Women of Chesterfield County, and several other women's rights groups across Virginia packed the committee chamber rooms of the Virginia General Assembly; when the chairmen did not bring up the ERA for a vote, they demanded, to resulting in applause in the room that the resolutions be given a fair hearing and vote. The House committee did not bring up the resolutions for consideration, and the Virginia Senate Rules Committee voted to table the resolution until the following year, citing an alleged statement from an official at the National Archives and Records Administration.[119][120]

The National Archives and Records Administration later noted that the alleged statement had never occurred. "'The Archivist of the United States has not taken such a stance and has never issued an opinion on this matter either officially or unofficially,' said the agency’s director of communications, James Pritchett, in a statement."[121]

Subsequent congressional action

The amendment has been reintroduced in every session of Congress since 1982. Senator Ted Kennedy (D-Massachusetts) championed it in the Senate from the 99th Congress through the 110th Congress. Senator Robert Menendez (D-New Jersey) introduced the amendment symbolically at the end of the 111th Congress and has supported it in the 112th Congress. In the House of Representatives, Carolyn Maloney (D-New York) has sponsored it since the 105th Congress,[122] most recently in August 2013.[123]

In 1983, the ERA passed through House committees with the same text as in 1972; however, it failed by six votes to achieve the necessary two-thirds vote on the House floor. That was the last time that the ERA received a floor vote in either house of Congress.[124]

At the start of the 112th Congress on January 6, 2011, Senator Menendez, along with Representatives Maloney, Jerrold Nadler (D-New York) and Gwen Moore (D-Wisconsin), held a press conference advocating for the Equal Rights Amendment's adoption.[125]

The 113th Congress had a record number of women. On March 5, 2013, the ERA was reintroduced by Senator Menendez as S.J. Res. 10.[126][127]

The "New ERA" introduced in 2013, sponsored by Representative Carolyn B. Maloney, adds an additional sentence to the original text: "Women shall have equal rights in the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction."[128]

Proposed removal of ratification deadline

On March 8, 2011, the 100th anniversary of International Women's Day, Representative Tammy Baldwin (D-Wisconsin) introduced legislation (H.J. Res. 47) to remove the congressionally imposed deadline for ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment.[129] Resolution co-sponsors included Representatives Robert Andrews (D-New Jersey), Jackie Speier (D-California), Luis Gutierrez (D-Illinois), Chellie Pingree (D-Maine) and Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-Florida). On March 22, 2012, the 40th anniversary of the ERA's congressional approval, Senator Benjamin L. Cardin (D-Maryland) introduced (S.J. Res. 39) – which is worded with slight differences from Representative Baldwin's (H.J. Res. 47). Senator Cardin was joined by ten other Senators who added their names to the Senate Joint Resolution.[130]

On February 24, 2013, the New Mexico House of Representatives adopted House Memorial No. 7 asking that the congressionally-imposed deadline for ERA ratification be removed.[131][132] House Memorial No. 7 was officially received by the U.S. Senate on January 6, 2014, was designated as "POM-175", was referred to the Senate's Committee on the Judiciary, and was published verbatim in the Congressional Record at page S24.[133]

State equal rights amendments

Twenty-four states and the District of Columbia have adopted constitutions or constitutional amendments providing that equal rights under the law shall not be denied because of sex. Most of these provisions mirror the broad language of the ERA, while the wording in others resembles the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.[134] The 1879 Constitution of California contains the earliest state equal rights provision on record. Narrowly written, it limits the equal rights conferred to "entering or pursuing a business, profession, vocation, or employment". Near the end of the 19th century two more states, Wyoming (1890) and Utah (1896), included equal rights provisions in their constitutions. These provisions were broadly written to ensure political and civil equality between women and men.[135] Several states crafted and adopted their own equal rights amendments during the 1970s and 1980s, while the ERA was before the states, or afterward.

Some state equal rights amendments and original constitutional equal rights provisions are:[135][136]

Alaska – No person is to be denied the enjoyment of any civil or political right because of race, color, creed, sex or national origin. The legislature shall implement this section. Alaska Constitution, Article I, §3 (1972)

California – A person may not be disqualified from entering or pursuing a business, profession, vocation, or employment because of sex, race, creed, color, or national or ethnic origin. California Constitution, Article I, §8 (1879)

Colorado – Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the state of Colorado or any of its political subdivisions because of sex. Colorado Constitution, Article II, §29 (1973)

Connecticut – No person shall be denied the equal protection of the law nor be subjected to segregation or discrimination in the exercise or enjoyment of his or her civil or political rights because of religion, race, color, ancestry, national origin, sex or physical or mental disability. Connecticut Constitution, Article I, §20 (1984)

Illinois – The equal protection of the laws shall not be denied or abridged on account of sex by the State or its units of local government and school districts. Illinois Constitution, Article I, §18 (1970)

Iowa – All men and women are, by nature, free and equal and have certain inalienable rights – among which are those of enjoying and defending life and liberty, acquiring, possessing and protecting property, and pursuing and obtaining safety and happiness. Iowa Constitution, Article I, §1 (1998)

Maryland – Equality of rights under the law shall not be abridged or denied because of sex. Maryland Constitution, Declaration of Rights, Article 46 (1972)

Massachusetts – All people are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights; among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties; that of acquiring, possessing and protecting property; in fine, that of seeking and obtaining their safety and happiness. Equality under the law shall not be denied or abridged because of sex, race, color, creed or national origin. Massachusetts Constitution, Part 1, Article 1 as amended by Article CVI by vote of the People, (1976)

Montana – Individual dignity. The dignity of the human being is inviolable. No person shall be denied the equal protection of the laws. Neither the state nor any person, firm, corporation, or institution shall discriminate against any person in the exercise of his civil or political rights on account of race, color, sex, culture, social origin or condition, or political or religious ideas. Montana Constitution, Article II, §4 (1973)

Oregon – Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the state of Oregon or by any political subdivision in this state on account of sex. Oregon Constitution, Article I, §46 (2014)

Utah – The rights of citizens of the State of Utah to vote and hold office shall not be denied or abridged on account of sex. Both male and female citizens of this State shall enjoy all civil, political and religious rights and privileges. Utah Constitution, Article IV, §1 (1896)

Washington, DC – It is the intent of the Council of the District of Columbia, in enacting this chapter, to secure an end in the District of Columbia to discrimination for any reason other than that of individual merit, including, but not limited to, discrimination by reason of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, age, marital status, personal appearance, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression familial status, family responsibilities, matriculation, political affiliation, genetic information, disability, source of income, status as a victim of an intrafamily offense, and place of residence or business. District of Columbia Code (Title 2, Chapter 14, Human Rights Act of 1977, as Amended Mar. 2007)

Wyoming – In their inherent right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, all members of the human race are equal. Since equality in the enjoyment of natural and civil rights is only made sure through political equality, the laws of this state affecting the political rights and privileges of its citizens shall be without distinction of race, color, sex, or any circumstance or condition whatsoever other than the individual incompetency or unworthiness duly ascertained by a court of competent jurisdiction. The rights of citizens of the state of Wyoming to vote and hold office shall not be denied or abridged on account of sex. Both male and female citizens of this state shall equally enjoy all civil, political and religious rights and privileges. Wyoming Constitution, Articles I and VI (1890)

See also

References

- ↑ Olson, James S.; Mendoza, Abraham O. (2015-04-28). American Economic History: A Dictionary and Chronology: A Dictionary and Chronology. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781610696982.

- ↑ Miller, Eric C. (2015-06-19). "Phyllis Schlafly's "Positive" Freedom: Liberty, Liberation, and the Equal Rights Amendment". Rhetoric & Public Affairs. 18 (2): 277–300. ISSN 1534-5238.

- 1 2 3 "New Drive Afoot to Pass Equal Rights Amendment". www.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- ↑ "Unbelievably, women still don't have equal rights in the Constitution". Los Angeles Times. January 5, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- ↑ Colin Dwyer; Carrie Kaufman (March 21, 2017). "Nevada Ratifies The Equal Rights Amendment ... 35 Years After The Deadline". NPR. Retrieved March 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Congressional Record - April 5, 2017" (PDF).

- ↑ ((cite web|url=https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CREC-2018-09-12/pdf/CREC-2018-09-12-pt1-PgS6141-3.pdf#page=1%7Ctitle=Congressional Record - September 12, 2018))

- ↑ 86 Stat. 1523

- ↑ "Proposed Amendments Not Ratified by States" (PDF). United States Government Printing Office. Retrieved June 1, 2013.

- ↑ "Who Was Alice Paul?". Alice Paul Institute. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- 1 2 Henning, Arthur Sears (26 September 1921). "WOMAN'S PARTY ALL READY FOR EQUALITY FIGHT; Removal Of All National and State Discriminations Is Aim. SENATE AND HOUSE TO GET AMENDMENT; A Proposed Constitutional Change To Be Introduced On October 1". The Baltimore Sun. p. 1.

- ↑ "Who was Alice Paul". Alice Paul Institute. Retrieved 2016-02-02.

- ↑ ""Lucretia Mott" National Park Service". National Park Service. United States Government. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ↑ "Equal Rights Amendments, 1923-1972". history.hanover.edu. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- ↑ Davis, Flora (1999-01-01). Moving the Mountain: The Women's Movement in America Since 1960. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252067822.

- ↑ Sealander, Judith (1982). "Feminist Against Feminist: The First Phase of the Equal Rights Amendment Debate, 1923–1963". South Atlantic Quarterly. 81 (2): 147–161.

- ↑ Cott, Nancy (1984). "Feminist Politics in the 1920s: The National Woman's Party". Journal of American History. 71 (1): 43–68. JSTOR 1899833.

- ↑ Ware, Susan, ed. (1997). "New Dilemmas for Modern Women". Modern American Women: A Documentary History. McGraw-Hill Higher Education. ISBN 0-07-071527-0.

- ↑ Cott, Nancy (1987). The Grounding of Modern Feminism. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04228-0.

- ↑ Cobble, Dorothy Sue (2004). The Other Women's Movement: Workplace Justice and Social Rights in Modern America. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 51. ISBN 0-691-06993-X.

- ↑ Dollinger, Genora Johnson (1997). "Women and Labor Militancy". In Ware, Susan. Modern American Women: A Documentary History. McGraw-Hill Higher Education. pp. 125–126. ISBN 0-07-071527-0.

- ↑ McBride, Genevieve G. (2005). "'Forward' Women: Winning the Wisconsin Campaign for the Country's First ERA, 1921". In Boone, Peter G. Watson. The Quest for Social Justice III: The Morris Fromkin Memorial Lectures, 1992–2002. Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. ISBN 1-879281-26-0.

- ↑ Keetley, Dawn; Pettegrew, John, eds. (2005). Public Women, Public Words: A Documentary History of American Feminism, Volume II: 1900 to 1960. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 284–5. ISBN 9780742522251.

- ↑ "Conversations with Alice Paul: Woman Suffrage and the Equal Rights Amendment". cdlib.org. Suffragists Oral History Project.

- ↑ "What's in a Name? Does it matter how the Equal Rights Amendment is worded?". jofreeman.com.

- 1 2 Cynthia Ellen Harrison (1989). On Account of Sex: The Politics of Women's Issues, 1945-1968. University of California Press. pp. 31–32. ISBN 9780520909304.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York, New York: Basic Books. pp. 245–248. ISBN 0-465-04195-7.

- ↑ Jo Freeman (2002). A Room at a Time: How Women Entered Party Politics. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-8476-9805-9.

- ↑ Kennedy, John F (October 21, 1960). "Letter to Mrs. Emma Guffey Miller, Chairman of the National Woman's Party". ucsb.edu.

- 1 2 "Peterson, Esther Eggertsen". Facts on File History Database. Infobase Learning.

- ↑ Joseph M. Siracusa (2012). Encyclopedia of the Kennedys: The People and Events That Shaped America. ABC-CLIO. p. 864. ISBN 9781598845396.

- ↑ Maurine Hoffman Beasley (1987). Eleanor Roosevelt and the Media: A Public Quest for Self-fulfillment. University of Illinois Press. p. 184. ISBN 9780252013768.

- ↑ Keetley, Dawn; Pettegrew, John, eds. (2005). Public Women, Public Words: A Documentary History of American Feminism, Volume III: 1960 to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 251. ISBN 9780742522367.

- 1 2 3 Nation, Women on Time (New York), September 7, 1970 Archived April 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 Voichita Nechescu (June 5, 2006). Becoming The Feminist Subject. Conscious-Raising Groups in Second Wave Feminism. Proquest. p. 209. ISBN 0542771683. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ↑ "GRIFFITHS, Martha Wright | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- ↑ 117 Congressional Record 35815

- ↑ "Congressional record". archive.org.

- ↑ Cruikshank, Kate. "The Art of Leadership: A Companion to an Exhibition from the Senatorial Papers of Birch Bayh, United States Senator from Indiana, 1963–1980". Indiana University. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ Johnson, Jone (October 31, 2017). "Which States Ratified the ERA and When Did They Ratify?". Thoughtco.com. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- 1 2 "ERA: History". www.equalrightsamendment.org. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- ↑ Gladstone, Leslie W. CRS Report 85-154 GOV: The Proposed Equal Rights Amendment. p. 33.

- ↑ Watson, Tara; Rose, Melody (2010). "She Flies With Her Own Wings: Women in the 1973 Oregon Legislative Session". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 111 (1): 38–63.

- ↑ MacPherson, Myra; MacPherson, Myra (1977-01-19). "Indiana Ratifies the ERA - With Rosalynn Carter's Aid". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2017-03-22.

- ↑ "Nevada ratifies Equal Rights Amendment decades past deadline". Las Vegas Now. March 22, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ↑ Rick Pearson, Bill Lukitsch (May 30, 2018). "Illinois House approves Equal Rights Amendment". The Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 30, 2018.

- ↑ "Authentication and Proclamation: Proposing a Constitutional Amendment". Justia. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ↑ Hatch, Orrin G. (1983). "The Equal Rights Amendment: Myths and Realities".

- ↑ "ERA Supporter Vetoes Resolution". The Tuscaloosa News. March 21, 1978. Retrieved November 1, 2016 – via Google News.

- ↑ "NOW v. Idaho | 459 U.S. 809 (1982)". Retrieved 2018-07-26.

- ↑ https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1979-pt4/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1979-pt4-4-2.pdf#page=43

- ↑ https://www.congress.gov/content/conan/pdf/GPO-CONAN-2017.pdf#page=1031

- ↑ Magliocca, Gerald N. (June 22, 2018). "Buried Alive: The Reboot of the Equal Rights Amendment". Social Science Research Network. p. 10. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- ↑ Hollingsworth v. Virginia, 3 U.S. (3 Dall.) 378 (1798)

- ↑ Carver, Joan S. (1982). "The Equal Rights Amendment and the Florida Legislature". Florida Historical Quarterly. 60 (4): 455–481. JSTOR 30149853.

- ↑ Harriett Woods, Stepping Up to Power: The Political Journey of American Women (2000); memoir of ERA leader in Missouri legislature

- ↑ Donald G. Mathews and Jane S. De Hart, Sex, Gender, and the Politics of ERA: A State and the Nation (1992) focus on debate in North Carolina

- ↑ Scott, Wilbur J. (1985). "The equal rights amendment as status politics". Social Forces. 64 (2): 499–506. doi:10.1093/sf/64.2.499.

- ↑ Goodman, Patricia W. (1978). "The ERA in Virginia: A Power Playground". Southern Exposure. 6 (3): 59–62.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-02-03. Retrieved 2016-01-27.

- ↑ Parry, Janine A. (2000). "'What Women Wanted': Arkansas Women's Commissions and the ERA". Arkansas Historical Quarterly. 59 (3): 265–298. JSTOR 40027988.

- ↑ Martha H. Swain; et al. (2010). Mississippi Women: Their Histories, Their Lives. U of Georgia Press. p. 289. ISBN 9780820333939.

- ↑ Will, George F. (February 13, 1994). "Night of the Living Dead Amendment" (PDF). Washington Post via National Right to Life Committee. Retrieved 2014-01-05.

- ↑ Francis, Roberta W. "Frequently Asked Questions". Alice Paul Institute. Retrieved 2009-08-14.

- ↑ Section 3 of the Eighteenth Amendment, Section 6 of the Twentieth Amendment, Section 3 of the Twenty-first Amendment, Section 2 of the Twenty-second Amendment, and Section 4 of the rejected District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment

- ↑ Volume 92, United States Statutes At Large, page 3799

- ↑ Equal Rights Amendment - Extension of ratification deadline Archived October 19, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ O'Dea, Suzanne (1999). From Suffrage to the Senate: An Encyclopedia of American Women in Politics, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 244. ISBN 9780874369601.

- ↑ Nicholson, Zoe Ann (2004). The Hungry Heart: A Woman's Fast for Justice. Lune Soleil Press. ISBN 0972392831.

- ↑ Sheppard, Nathaniel (June 24, 1982). "Women say they'll end fast but not rights fight". The New York Times. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ↑ Letter to House Judiciary Committee, June 14, 1978

- ↑ "STATE OF IDAHO v. FREEMAN | 529 F.Supp. 1107 (1981) | pp110711473 | Leagle.com". Leagle. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ↑ Memorandum of Gerald P. Carmen, Administrator of General Services, July 1982.

- ↑ "Now v. Idaho". eagleforum.org.

- ↑ "Coleman v. Miller".

- 1 2 Id.

- ↑ "Minutes, Hearing of the Assembly Committee on Legislative Operations and Elections" (PDF). , p.16 (Mar. 7, 2017).

- ↑ "Washington Post".

- ↑ See Virginia Attorney General Opinion Letter, supra, at 4.

- ↑ Id., at 7.

- ↑ "ERA: Why". www.equalrightsamendment.org. Retrieved 2017-04-06.

- ↑ Ginsburg, Ruth Bader (1973). "The Need for the Equal Rights Amendment". American Bar Association Journal. 59 (9): 1013–1019. JSTOR 25726416.

- ↑ "ERA: History". www.equalrightsamendment.org. Retrieved 2017-04-11.

- ↑ "July 9, 1978: Feminists Make History With Biggest-Ever March for the Equal Rights Amendment | Feminist Majority Foundation Blog". feminist.org. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- ↑ Times, Winston Williams, Special To The New York (1982-06-07). "THOUSANDS MARCH FOR EQUAL RIGHTS". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- ↑ ""All Our Problems Stem from the Same Sex Based Myths": Gloria Steinem Delineates American Gender Myths during ERA Hearings". historymatters.gmu.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- 1 2 SEDWICK, CATHY; WILLIAMS, REBA (1976-01-01). "BLACK WOMEN AND THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT". The Black Scholar. 7 (10): 24–29. JSTOR 41065957.

- ↑ "Shirley Anita St. Hill Chisholm, "For the Equal Rights Amendment" (10 August 1970)". archive.vod.umd.edu. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Rosalind (2008). Divided Lives: American Women in the Twentieth Century. Hill & Wang. p. 225. ISBN 9780809016310.

- ↑ Rhode, Deborah L. (2009). Justice and Gender: Sex Discrimination and the Law. Harvard University Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 9780674042674.

- ↑ "The Equal Rights Amendment". ushistory.org. Independence Hall Association.

- ↑ "Digital History". www.digitalhistory.uh.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-13.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Rosalind (2008). Divided Lives: American Women in the Twentieth Century. Hill & Wang. pp. 225–26. ISBN 9780809016310.

- ↑ Eilperin, Juliet. "New Drive Afoot to Pass Equal Rights Amendment". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ↑ Perlez, Jane (May 17, 1984). "Plan to omit rights amendment from platform brings objections". New York Times. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- ↑ Critchlow, p. 247

- ↑ Jane J. Mansbridge, Why we lost the ERA (University of Chicago Press, 1986) p 214.

- ↑ Jane Mansbridge, "Who's in Charge Here? Decision by Accretion and Gatekeeping in the Struggle for the ERA", Politics & Society (1984) 13#4 pp 343-382.

- ↑ Mansbridge, Why we lost the ERA (1986) p 110.

- ↑ Williams, Joan (1999). Unbending Gender: Why Family and Work Conflict and What To Do About It. Oxford UP. p. 147. ISBN 9780199840472.

- ↑ Glazer-Raymo, Judith (2001). Shattering the Myths: Women in Academe. Johns Hopkins UP. p. 19. ISBN 9780801866418.

- ↑ Critchlow and Stachecki (2008). The Equal Rights Amendment Reconsidered. pp. 157-8

- ↑ Francis, Roberta W. "The History Behind the Equal Rights Amendment". equalrightsamendment.org. Alice Paul Institute. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- ↑ David W. Brady and Kent L. Tedin, "Ladies in Pink: Religion and Political Ideology in the Anti-ERA Movement", Social Science Quarterly (1976) 56#4 pp 564-75

- ↑ Critchlow and Stachecki (2008). The Equal Rights Amendment Reconsidered. p. 160

- ↑ Francis, Roberta W. "The Three-State Strategy". equalrightsamendment.org. Alice Paul Institute in collaboration with the ERA Task Force of the National Council of Women's Organizations. Archived from the original on January 27, 2014. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ↑ "Coleman v. Miller". Justia. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

- ↑ "2009 National NOW Conference Resolutions: Equal Rights Amendment". National Organization for Women. June 21, 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-08-12. Retrieved 2009-08-14.

- ↑ Neale, Thomas H. (May 9, 2013), The Proposed Equal Rights Amendment: Contemporary Ratification Issues (PDF), Congressional Research Service

- ↑ Held, Herndon, and Stager, Allsion, Sheryl, and Danielle (1997). "The Equal Rights Amendment: Why the ERA Remains Legally Viable And Properly Before the States" (PDF). William & Mary Journal of Women and the Law. 3:113: 113–136.

- ↑ Neale, Thomas (May 9, 2013). "The Proposed Equal Rights Amendment: Contemporary Ratification Issues" (PDF). Retrieved May 25, 2017.

Congressional Research Service

- ↑ "ERA: Home". www.equalrightsamendment.org. Retrieved 2017-04-06.

- ↑ "Nevada Ratifies The Equal Rights Amendment ... 35 Years After The Deadline". NPR. Retrieved 2017-04-06.

- ↑ Brown, Matthew Hay. "As women march in D.C., Cardin co-sponsors new Equal Rights Amendment". baltimoresun.com. Retrieved 2017-04-06.

- ↑ says, Quora. "Let's Ratify the ERA: A Look at Where We Are Now". AAUW: Empowering Women Since 1881. Retrieved 2017-04-06.

- ↑ "Common Legal Questions About the ERA" (PDF). www.winston.com. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- ↑ "The ERA's Revival: Illinois Ratifies Equal Rights Amendment". WTTW. May 30, 2018. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Illinois Senate approves federal Equal Rights Amendment, more than 35 years after the deadline". April 12, 2018. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

- ↑ Wilson, Patrick (February 10, 2018). "Women pack committee rooms demanding Virginia debate ERA" (General Assembly 2018). Richmond, Virginia: Richmond Times-Dispatch. p. A9.

- ↑ Sullivan, Patricia (February 9, 2018). "Virginia's hopes of ERA ratification go down in flames this year". Washington Post. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ↑ Oliver, Ned (July 25, 2018). "Only one more state needs to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment. Will it be Virginia?". Virginia Mercury. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

- ↑ "The Equal Rights Amendment: 111th Congress" (PDF). maloney.house.gov. July 13, 2009.

- ↑ "Bill Summary & Status 113th Congress (2013 - 2014) H.J. Res. 56". loc.gov. Library of Congress.

- ↑ Randall, Vicky (1987). Women and Politics: An International Perspective. University of Chicago Press. p. 308. ISBN 9780226703923.

- ↑ "As Constitution is read aloud, Maloney, Menendez, Nadler, Moore cite need for Equal Rights Amendment". maloney.house.gov (Press release). January 6, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- ↑ "Bill Text 113th Congress (2013-2014) S.J.RES.10.IS". loc.gov. Library of Congress.

- ↑ Gray, Kaili Joy (March 7, 2013). "Democrats re-re-re-reintroduce Equal Rights Amendment ... but shhhh, don't tell anyone". dailykos.com.

- ↑ Neuwirth, Jessica (2015). Equal Means Equal. New York: The New Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-62097-039-3.

- ↑ "U.S. Rep. Baldwin: Seeks to speed ratification of Equal Rights Amendment". wispolitics.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2011-03-08.

- ↑ "All Bill Information (Except Text) for S.J.Res.39 - A joint resolution removing the deadline for the ratification of the equal rights amendment". congress.gov.

- ↑ 51st Legislature, State of New Mexico, First Session, 2013, House Memorial 7 (PDF)

- ↑ "Roundhouse roundup, Feb. 11, 2013". Las Cruces Sun-News. Archived from the original on 2014-02-03.

- ↑ 113th Congress, 2nd Session, "Congressional Record" (PDF), congress.gov (Vol. 160, No. 2), p. S21

- ↑ Gladstone, Leslie (August 23, 2004). "Equal Rights Amendment: State Provisions" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- 1 2 Leslie W. Gladstone (August 23, 2004). "Equal Rights Amendments: State Provisions" (PDF). CRS Report for Congress. Congressional Research Service - The Library of Congress. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 15, 2015.

- ↑ "VoteERA.org Equal Rights Amendment Women's Full Equality". VoteERA.org Equal Rights Amendment Women's Full Equality.

Further reading

- Baldez, Lisa; Epstein, Lee; Martin, Andrew D. (2006). "Does the U.S. Constitution Need an Equal Rights Amendment?" (PDF). Journal of Legal Studies. 35 (1): 243–283. doi:10.1086/498836.

- Bradley, Martha S. (2005). Pedestals and Podiums: Utah Women, Religious Authority, and Equal Rights. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books. ISBN 1-56085-189-9.

- Critchlow, Donald T. (2005). Phyllis Schlafly and Grassroots Conservatism: A Woman's Crusade. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-07002-4.

- Critchlow, Donald T., and Stachecki, Cynthia L. (2008). "The Equal Rights Amendment Reconsidered: Politics, Policy, and Social Mobilization in a Democracy", Journal of Policy History Volume 20, Number 1 online

- Dunlap, Mary C. (1976) "The Equal Rights Amendment and the Courts". Pepperdine Law Review Volume 3, Number 1 online

- Hatch, Orrin G. (1983). The Equal Rights Amendment: Myths and Realities, Savant Press.

- Kempker, Erin M. (2013) "Coalition and Control: Hoosier Feminists and the Equal Rights Amendment". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 34.2 (2013): 52-82. online

- Lee, Rex E. (1980). A Lawyer Looks at the Equal Rights Amendment. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press. ISBN 0-8425-1883-5.

- Mansbridge, Jane J. (1986). Why We Lost the ERA. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-50358-5.

- McBride, Genevieve G. (2005). "'Forward' Women: Winning the Wisconsin Campaign for the Country's First ERA, 1921.". In Peter Watson Boone (ed.). The Quest for Social Justice III. Milwaukee, WI: UW-Milwaukee. ISBN 1-879281-26-0.

- Neale, T. H. (2013). The proposed Equal Rights Amendment: Contemporary ratification issues (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service) online

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Equal Rights Amendment. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Jane Mansbridge ERA podcast

- Alice Paul Institute

- Ratify ERA 2018

- United4Equality

- VoteERA.org/

- Eagle Forum

- Women Matter

- ERA Coalition

- Katrina's Dream

- ERA Action

- 2015 article on attempts to revive the amendment in Virginia

- Ginsburg, Ruth Bader (7 April 1975). "Opinion: The Fear of the Equal Rights Amendment". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 3 May 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

But opponents continue a campaign appealing to our insecurity. The campaign theme is fear, fear of unsettling familiar and, for many men and women, comfortable patterns; fear of change, engendering counsel that we should not deviate from current arrangements, because we cannot fully forecast what an equal opportunity society would be like.

- SMITH, TAMMIE (Aug 26, 2018). "Hundreds attend event to support Virginia's effort to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved 28 August 2018.