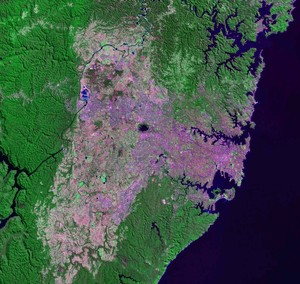

Cumberland Plain

| Cumberland Plain | |

| Sydney Plain | |

| Physiographic and geological feature | |

The Cumberland Plain, which mostly covers the sweeping Greater Western Sydney area. | |

| Name origin: Cumberland County, in honour of Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland.[1] | |

| Country | Australia |

|---|---|

| State | New South Wales |

| Region | Sydney bioregion |

| District | Cumberland County |

| City | Greater Sydney |

| River | |

| Coordinates | 33°45′S 151°00′E / 33.750°S 151.000°ECoordinates: 33°45′S 151°00′E / 33.750°S 151.000°E[1] |

| Area | 2,750 km2 (1,062 sq mi) |

The Cumberland Plain is a relatively flat region lying to the west of Sydney CBD in New South Wales, Australia. Cumberland Basin is the preferred physiographic and geological term for the low-lying plain of the Permian-Triassic Sydney Basin found between Sydney and the Blue Mountains.[2]

The Cumberland Plain has an area of roughly 2,750 square kilometres (1,060 sq mi). Shaping the geography of Sydney, it extends from 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) north of Windsor in the north, to Picton in the south; and from the Nepean-Hawkesbury River in the west almost to Sydney City's Inner West in the east. Much of the Sydney metropolitan area is located on the Plain. The Hornsby Plateau is located to the north and is dissected by steep valleys.[3]

The area lies on Triassic shales and sandstones. The region mostly consists of low rolling hills and wide valleys in a rain shadow area near the Blue Mountains. The annual rainfall of the plain is typically around 700–900 mm, and is generally lower than the elevated terrain that partially surrounds it. Common vegetation in the Cumberland Plain is eucalyptus trees. Soils in the plain are usually red and yellow in texture.[4]

The plain takes its name from Cumberland County, in which it is situated, one of the cadastral land divisions of New South Wales. The name Cumberland was conferred on the County by Governor Phillip in honour of Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland.[1] Being the most populous region in Australia, the Cumberland Plain is one of the fastest growing areas of the country in terms of population and it is home to a variety of Australian animal species, which are observable in the urban environments.[5]

Geology

Formed about 80 million years ago, the Cumberland Plain consists of not exactly flat plains; overall it is a low-lying area, largely over shale and labile sandstone, which derives its recognition largely by comparison with the surrounding uplands of harder quartzose Sydney sandstone. Relative to the surrounding higher sandstone lands, Hornsby and Blue Mountains Plateaux, it was an early matter of debate in Sydney physiographic circles as to whether the Cumberland Plain had gone down, or the surrounding plateaux had been raised up. Despite much study, especially along the western side at the Lapstone monocline, this complex matter is still not fully understood.[6] There are volcanic rocks from low hills in the shale landscapes. Swamps and lagoons are existent on the floodplain of the Nepean River.

The Wianamatta Plain, with many undulating hills of Wianamatta Group shales and sandstones, bounded by the Woronora and Illawarra Plateaus to the south, the Blue Mountains Plateau to the west and the Hornsby Plateau to the north/northeast. At the front of the Blue Mountains Plateau runs the Lapstone Structural Complex, which forms the western edge of the Cumberland Basin and Cumberland Plain. This is a north-south trending collection of reverse faults and monoclinal folds which extends generally north south for over 100 kilometres (62 mi). At the opposite side of the Cumberland Plain the Hornsby Plateau is fronted by the Hornsby Warp. That warp is topographically subtle in comparison to the Lapstone Structural Complex, and it is a feature which is poorly defined and inadequately defined in literature.

Prospect Hill in western Sydney is the largest assemblage of igneous rock in the Plain. The oval-shaped ridge was made many millions of years ago when volcanic material from the Earth's core actuated upwards and then sideways.[7] Slow erosion of the overlying layers of sedimentary rock by the flow of rainwater have eventually laid bare the edges of the volcanic and metamorphic rocks of the intrusion.[8] The western suburbs lie on the relatively flat, lowly elevated parts of the Cumberland Plain. Though there are a few hilly or relatively elevated regions on the plain. Western Sydney Parklands and the surrounding suburbs (such as Cecil Hills and Horsley Park), for instance, lies on a prominent ridge that is between 130 to 140 metres (430 to 460 ft) high.[2]

Bringelly Shale and Minchinbury Sandstone are often seen in the Plain's west.[9][10] Ashfield Shale is observed in the inner western suburbs.[11] These components are part of the Wianamatta Shale group.[12]

Rivers

Rivers in the Cumberland Plain are salient. The Nepean River rises to the south in the Woronora Plateau, and wraps around the western edge of the city. Parramatta River's headwaters are several local creeks including Toongabbie Creek and Hunts Creek, part of the upper Parramatta river catchment area. Hunt's creek flows from Lake Parramatta, a few kilometres North of Parramatta. Warragamba River flows 3.5 kilometres (2.2 mi) north-east from the Warragamba Dam spillway to its confluence with the Nepean River.[13]

The south and southwest of Sydney is drained by the Georges River, flowing north from its source near Appin, towards Liverpool and then turning east towards Botany Bay. The other major tributary of Botany Bay is the Cooks River, running through the inner-south western suburbs of Canterbury and Tempe. The Georges River estuary separates the main part of Sydney's urban area from the Sutherland Shire. The Woronora River, on the southern edge of the Sydney Plain, flows in a steep-sided valley from the Woronora Dam to the eastern estuary of the Georges River.

Minor waterways draining Sydney's western suburbs include South Creek and Eastern Creek, flowing into the Hawkesbury, and Prospect Creek draining into the Georges River.

Ecology

Flora

The plant communities in the Sydney region are sclerophyll forests. Dry sclerophyll forests are the most predominant plants in the Cumberland Plain. Wet sclerophyll forests generally lie on the Hornsby plateau, an elevated region north of the Plain. Dry sclerophyll forests contain eucalyptus trees which are usually in open woodlands that have dry shrubs and sparse grass in the understory.[14][6]

In 1820s, Peter Cunningham described the country west of Parramatta and Liverpool as "a fine timbered country, perfectly clear of bush, through which you might, generally speaking, drive a gig in all directions, without any impediment in the shape of rocks, scrubs, or close forest". This confirmed earlier accounts by Governor Phillip, who suggested that the trees were "growing at a distance of some twenty to forty feet from each other, and in general entirely free from brushwood..."[15][16]

Fauna

The Cumberland Plain is home to a variety of bird, insect, reptile and mammal species, including bats. Arachnid, amphibian and crustacean species are also present.[17] About 40 species of reptiles are found in the Cumberland Plain. 30 bird species exist in the urban areas, with the common ones being the Australian magpie, Australian raven, noisy miner and the pied currawong. Introduced birds include the common mynah, common starling and the house sparrow. 14 mammal species are widespread in the plain, with common species being those of bats and possums. The outskirts of the Cumberland Plain, such as those adjacent to large parks, have a great diversity of wildlife.[18]

Although not commonly spotted, these birds are also present in the Cumberland Plain:[19]

- Australian King-Parrot

- Brown goshawk

- Common Bronzewing

- Eastern Yellow Robin

- Golden Whistler

- Little Wattlebird

- Little raven

- Nankeen Kestrel

- New Holland Honeyeater

- Pallid Cuckoo

- Peregrine falcon

- Red-browed Finch

- Red Wattlebird

- Red-whiskered Bulbul

- Silvereye

- Tawny Frogmouth

- Turquoise parrot

- Whistling kite

- White-bellied sea-eagle

Reptiles, mammals and amphibians:[20][21]

- Australian blue-tongued skink

- Australian water dragon

- Bibron's toadlet

- Bleating tree frog

- Broad-headed snake

- Common bent-wing bat

- Common brushtail possums

- Common death adder

- East-coast free-tailed bat

- Great barred frog

- Giant burrowing frog

- Leaf Green Tree Frog

- Long-nosed Bandicoot

- Squirrel glider

- Sugar glider

- Three-toed earless skink

- Yellow-bellied glider

Arthropods:[22]

- Australian carpet beetle

- Australian garden orb weaver spider

- Australian grapevine moth

- Brush-tailed phascogale

- Emperor gum moth

- Feathertail Glider

- Giant centipede

- Green-head ant

- Jalmenus evagoras

- Netrocoryne repanda

- Nezara viridula

- Pill bug

- Plague soldier beetle

- Punctate flower chafer

- Redback spiders

- Zizina labradus

Woodlands

The sclerophyll woodlands are situated on a nutrient-poor alluvium deposited by the Nepean River from sandstone and shale bedrock in the Blue Mountains. Despite this, they support a tremendous regional biodiversity.[23] Cleared and used first for agriculture and then for urban development, most of the ecological communities that originally flourished on the plain are now considered endangered.[24] They include:

- Cumberland Plain Woodland - Found scattered in most parts of Greater Western Sydney, it is a dry woodland remnant that contains waxy-leaved shrubs, twiners, herbs and small trees in a grassy understorey. It has a number of sub-regions:[25] Moist Shale Woodlands, Western Sydney dry rainforest, Shale gravel transition forest, and Shale gravel transition forest, among others.[26][27]

- Sydney coastal river-flat forest - Found on the river flats of the coastal floodplains in most parts of the plain that has rivers or creeks, it has an open tree layer of eucalypts which may surpass 40 m in height.[28]

- Elderslie banksia scrub - Dominated by Coastal Banksia and found near Camden, it has a diverse understorey sets of shrub species.[29]

- Sydney turpentine ironbark forest - Characterized by thick shrubs and dominated by Syncarpia glomulifera, it is a tall open forest with trees as high as 30 meteres and is found on shale and shale-meliorated soils found in small pockets at Campbelltown, Heathcote and Menai.[30][31]

- Castlereagh swamp woodland - A swampy sclerophyll forest affiliated with sporadically flooded soils containing Tertiary, Holocene and Quaternary sand deposits. It is found in low-elevated areas of Liverpool City Council and in Voyager Point, and is made up of moderate to heavy cover of paperbark trees.[32]

- Agnes Banks woodland - A low laying woodland community with Scribbly Gums being the dominant canopy, it is found in the Hawkesbury River in the City of Penrith and near Richmond.[33]

- Cooks River/Castlereagh ironbark forest - Found in Castlereagh and Holsworthy, and a few remnants in the cities of Auburn, Bankstown and Liverpool, it is an ironbark shrub-grass forest located in western Sydney that sit on gravelly-clay soils and is made up of a moderately tall open eucalyptus forest or woodland to a low compact brush of paperbarks with nascent eucalypts. Broad-leaved ironbark (Eucalyptus fibrosa) is the most commonly spotted tree.[34]

- Sydney coastal river-flat forest - Found on the river flats of the coastal floodplains in most parts of the plain that has rivers or creeks. It has an open tree layer of eucalypts which may surpass 40 m in height.[28]

Protection

Under Federal environmental legislation, six of the above ecological communities are protected as four "matters of national environmental significance". Some are grouped together into broader communities that share similarities in landscape position, structure and/or species.

The four nationally defined and protected threatened ecological communities are: Blue Gum High Forest of the Sydney Basin Bioregion; Cumberland Plain Shale Woodlands and Shale-Gravel Transition Forest; Shale/Sandstone Transition Forest; Turpentine-Ironbark Forest in the Sydney Basin Bioregion; and Western Sydney Dry Rainforest and Moist Woodland on Shale. The plain has 300 different native plants and is home to over 20 threatened bird and animals.[35]

Cumberland Plain communities are protected in a number of council reserves, plus the Lower Prospect Canal Reserve, Scheyville National Park, Windsor Downs Nature Reserve, Leacock Regional Park and Mulgoa Nature Reserve and Mount Annan Botanic Garden. Cumberland Plain Woodland, of which around six per cent remains in isolated stands, was the first Australian ecological community to be assigned this status.[36]

Agriculture

The western portion of the Cumberland Plain mainly consists of sparsely populated, vast, rural grasslands with undulating hills and scenic vistas. The Sydney western suburbs of Mount Vernon, Kemps Creek, Orchard Hills, Luddenham, Mulgoa, Bringelly, Silverdale and Horsley Park, among others, lie in this agricultural countryside, adjacent to the footsteps of the Blue Mountains westwards of these country plains.[37] Furthermore, Abbotsbury, Cecil Hills and Glenmore Park were farms through until the 1980s when it was decided to redevelop them for housing. The area around the site of Regentville has remained largely rural, if hemmed in somewhat by the modern residential suburbs of Jamisontown and Glenmore Park.[38]

In the 1800s, John Blaxland built an original wooden weir at "Grove Farm" (now known as Wallacia) for a sandstone flour mill and additional brewery. The land was also used for wheat farming until 1861 when wheat rust infected the entire crop.[39] The rural regions were chiefly one of dairying and grazing during the 19th century, but in the early 20th century - because of its rural atmosphere and proximity to Sydney - tourism developed as people opened their homes as guest houses. Today, the rural areas include a number of orchards and vineyards in the meadows. Vegetable farming and fruit picking are common activities.[40]

Location

The Cumberland Plain starts westwards of the inner west, towards south-western Sydney, and into the Greater Western Sydney area. It is within the local government areas of Blacktown, Burwood, Camden, the western portion of Campbelltown, Canada Bay, Canterbury-Bankstown, Cumberland, Fairfield, Georges River, Hawkesbury, the Western outskirts of the Inner West Council, Liverpool, Parramatta, Penrith, Ryde, Strathfield, The Hills Shire, Wingecarribee, and Wollondilly.

The rest of the Sydney regions such as Sydney CBD (including the City of Sydney), North Shore, Northern Beaches, Eastern Suburbs, Southern Sydney (including Sutherland Shire), Hills District, Hornsby Shire and the Forest District do not lie in the Cumberland Plain.[41]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Cumberland". Geographical Names Register (GNR) of NSW. Geographical Names Board of New South Wales. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- 1 2 Carter, Lewis (2011). Tectonic Control of Cenozoic Deposition in the Cumberland Basin, Penrith/Hawkesbury Region, New South Wales (Bachelor of Science (Honours) thesis). School of Earth & Environmental Sciences, University of Wollongong.

- ↑ "Sydney Basin". Office of Environment and Heritage. 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ↑ Sydney Basin Subregions

- ↑ Cooke, J.; Willis, T.; Groves, R. (2005). "Impacts of woody weeds on Cumberland Plain Woodland biodiversity". In Pellow, B.; Morris, C.; Bedward, M.; Hill, S.; Sanders, J.; Clark, J. The ecology and management of Cumberland Plain habitats: a symposium. Campbelltown: University of Western Sydney. p. 7.

- 1 2 Benson, D. H.; Howell, J. (1990). Taken for Granted: The Bushland of Sydney and Its Suburbs. Sydney: Kangaroo Press and the Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney.

- ↑ Compton, Keith (21 February 2017). "Prospect, New South Wales". Mindat. Hudson Institute of Mineralogy. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ↑ Morrison, Conybeare (2005). Prospect Hill Conservation Management Plan. Holroyd City Council.

- ↑ Lovering, J. F. "Bringelly Shale" (PDF). STRATIGRAPHY OF' THE WIANAMATTA GROUP. Australian Museum. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ↑ "Minchinbury Sandstone". Stratigraphic Search Geoscience Australia. Australian Government. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ↑ Packham 1969, p. 417–421.

- ↑ Fairley & Moore 2000, p. 19.

- ↑ "Catchments: Access in Special Areas". Sydney Catchment Authority. Government of New South Wales. 26 March 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- ↑ "Dry sclerophyll forests (shrub/grass sub-formation)". NSW Environment & Heritage. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ Kohen, J. (September 1996). "The Impact of Fire: An Historical Perspective". Australian Plants Online. Society for Growing Australian Plants.

- ↑ "Sydney Coastal Dry Sclerophyll Forests". NSW Environment & Heritage. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ↑ Williams, J.; et al. (2001). "Biodiversity, Australia State of the Environment Report 2001" (Theme Report). Canberra: CSIRO Publishing on behalf of the Department of the Environment and Heritage. ISBN 0-643-06749-3.

- ↑ Burton, Thomas C. (1993). "9. Family Microhylidae" (PDF). Fauna of Australia series, Environment Australia website. Canberra: Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Australian Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ↑ Australian Museum Online. "Crows and Ravens". Archived from the original on 1 September 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2007.

- ↑ Cogger, H. G. (2000). Reptiles and Amphibians of Australia. Reed New Holland.

- ↑ Green, D. (1973). "Re reptiles of the outer north-western suburbs of Sydney". Herpetofauna. 6 (2): 2–5.

- ↑ Lomov, B. (2005). Plant-insect interactions as indicators for restoration ecology (PhD thesis). Sydney: University of Sydney.

- ↑ Nichols P. W. B. (2005). Evaluation of restoration: a grassy woodland (PhD thesis). Hawkesbury: University of Western Sydney.

- ↑ NPWS (2002a) Native Vegetation of the Cumberland Plain - Final Edition, NPWS, Sydney.

- ↑ James, T. (1997). Native flora in Western Sydney: Urban Bushland Biodiversity Survey. NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service.

- ↑ Earth Resource Analysis PL (1998). Cumberland Plains Woodland: Trial Aerial Photographic interpretation of remnant woodlands, Sydney. NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service – Sydney Zone (Unpublished report)

|format=requires|url=(help). - ↑ Fairley, A.; Waterhouse, D. (2005). West Sydney Wild – Exploring Nature in Sydney’s Western Suburbs. Dural, NSW: Rosenberg Publishing Pty Ltd.

- 1 2 James, T.; McDougall, L.; Benson, D. (1999). Rare Bushland plants of Western Sydney. Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney.

- ↑ Harden, G. J., ed. (2000–2002). The Flora of New South Wales. 1–2 (Revised ed.). University of New South Wales Press.

- ↑ Andrew, D. (2001). Post fire vertebrate fauna survey: Royal and Heathcote National Parks and Garawarra State Recreation Area. Report to NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Sydney South Region.

- ↑ "ENDANGERED ECOLOGICAL COMMUNITY INFORMATION: Sydney Turpentine-Ironbark Forest" (PDF). NSW Department of Environment & Climate Change. Ryde City Council. February 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 2 July 2007.

- ↑ DEC 2004, Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub Endangered Ecological Community Recovery Plan. NSW Department of Environment and Conservation, Hurstville.

- ↑ Tozer, M. G. (2003). "The native vegetation of the Cumberland Plain, western Sydney: systematic classification and field identification of communities". Cunninghamia. 8: 1–75.

- ↑ Auburn Council 2004, Auburn Council State of the Environment Report 2003-2004. Auburn Council, Auburn

- ↑ NPWS (2002b) Interpretation Guidelines for the Native Vegetation Maps of the Cumberland Plain, Western Sydney, Final Edition, NPWS, Sydney.

- ↑ http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl

- ↑ Australian 1981, p. 2/11.

- ↑ "An old family". The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954). New South Wales: National Library of Australia. 21 March 1914. p. 4. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ↑ "NEWINGTON FARM". The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954). NSW: National Library of Australia. 5 April 1930. p. 9. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ↑ "Census of population and housing: selected characteristics for urban centres, Australia" (PDF). Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2003. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ↑ Map of the Cumberland Plain (Map). New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage. 13 December 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

External links

- Botanic Gardens Trust - Mount Annan Botanic Garden webpage

- Australian Government: Department of the Environment and Heritage - Cumberland Plain Woodland: Woodlands Vanishing from Sydney's Outskirts

- "Cumberland Plain Recovery Plan". Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water (NSW). 1 January 2011. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-74232-808-9.