Karelian language

| Karelian | |

|---|---|

|

karjal kariela karjala | |

| Native to | Russia, Finland |

| Region | Republic of Karelia, Tver Oblast |

| Ethnicity | Karelians |

Native speakers | 36,000 (1994–2010)[1] |

| Latin (Karelian alphabet) Cyrillic (Russia) | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 |

krl |

| ISO 639-3 |

krl |

| Glottolog |

kare1335[4] |

| |

Karelian (karjala, karjal or kariela) is a Finnic language spoken mainly in the Russian Republic of Karelia. Linguistically, Karelian is closely related to the Finnish dialects spoken in eastern Finland, and some Finnish linguists have even classified Karelian as a dialect of Finnish. Karelian is not to be confused with the Southeastern dialects of Finnish, sometimes referred to as karjalaismurteet ("Karelian dialects") in Finland.[5]

There is no single standard Karelian language. Each writer writes in Karelian according to their own dialectal form. Three main written standards have been developed, for North Karelian, Olonets Karelian and Tver Karelian. All variants are written with the Latin-based Karelian alphabet, though the Cyrillic script has been used in the past.

Classification

Karelian belongs to the Finnic branch of the Uralic languages, and it is closely related to Finnish.[6] Finnish and Karelian have common ancestry in the Proto-Karelian language spoken in the coast of Lake Ladoga in the Iron Age, and Karelian forms a dialect continuum with the Eastern dialects of Finnish.[7] Earlier, some Finnish linguists classified Karelian as a dialect of Finnish, sometimes known in older Finnish literature as Raja-Karjalan murteet ('Border Karelian dialects'), but today Karelian is seen as a distinct language. Besides Karelian and Finnish, the Finnic subgroup also includes Estonian and some minority languages spoken around the Baltic Sea.

Geographic distribution

Karelian is spoken by about 100,000 people, mainly in the Republic of Karelia, Russia, although notable Karelian-speaking communities can also be found in the Tver region northwest of Moscow. Previously, it was estimated that there were 5,000 speakers in Finland, mainly belonging to the older generations,[5] but more recent estimates have increased that number to 30,000.[8] Due to post-World War II mobility and internal migration, Karelians now live scattered throughout Finland, and Karelian is no longer spoken as a local community language.[9]

Official status

In the Republic of Karelia, Karelian has official status as a minority language,[3] and since the late 1990s there have been moves to pass special language legislation, which would give Karelian an official status on par with Russian.[10] Karelians in Tver Oblast have a national-cultural autonomy which guarantees the use of the Karelian language in schools and mass media.[11] In Finland, Karelian has official status as a non-regional national minority language within the framework of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.[12]

Dialects

The Karelian language has two main varieties, which can be considered as dialects or separate languages: Karelian Proper, which comprises North Karelian and South Karelian (including the Tver enclave dialects); and Olonets Karelian. These varieties constitute a continuum of dialects, the ends of which are no longer mutually intelligible.[9] Varieties can be further divided into individual dialects:[13]

- Karelian Proper

- North Karelian (spoken in the parishes of Jyskyjärvi, Kieretti, Kiestinki, Kontokki, Oulanka, Paanajärvi, Pistojärvi, Suomussalmi, Uhtua, Usmana, Vitsataipale and Vuokkiniemi)

- South Karelian (spoken in the parishes of Ilomantsi, Impilahti, Korpiselkä, Mäntyselkä, Paatene, Porajärvi, Repola, Rukajärvi, Suikujärvi, Suistamo, Suojärvi and Tunkua; and additionally in the enclaves of Tver, Tihvinä and Valdai)

- Tver Karelian[14]

- Dorža dialect

- Maksuatiha dialect

- Ruameška dialect

- Tolmattšu dialect

- Vesjegonsk (Vessi) dialect

- Tver Karelian[14]

- Olonets Karelian or Livvi (spoken in the parishes of Kotkatjärvi, Munjärvi, Nekkula-Riipuškala, Salmi, Säämäjärvi, Tulemajärvi, Vieljärvi and Vitele)

Phonology

Vowels

Monophthongs

The Karelian language has 8 vowels, if not including vowel length:

| Front | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | ||

| Close | i /i/ | y /y/ | u /u/ |

| Mid | e /e/ | ö /œ/ | o /o/ |

| Open | ä /æ/ | a /ɑ/ | |

Only the close vowels /i/, /y/ and /u/ may occur long.[15] The original Proto-Finnic long mid and open vowels have been diphthongized: *ee, *öö, *oo > /ie/, /yö/, /uo/ (as also in Finnish); *aa, *ää > /oa/, /eä/ or /ua/, /iä/ (as also in Savonian dialects of Finnish).

Diphthongs

North Karelian[16] and Olonets Karelian[17] have 21 diphthongs:

| Front-harmonic | Neutral | Back-harmonic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front+neutral | Front+front | Neutral+front | Neutral+back | Back+neutral | Back+back | ||

| Open to close | äi | äy | ai | au | |||

| Mid to close | öi | öy | ey | ei | eu | oi | ou |

| Close | yi | iy | iu | ui | |||

| Close to mid | yö | ie | uo | ||||

| Close to open | yä | iä | ua | ||||

Triphthongs

In addition to the diphthongs North Karelian has a variety of triphthongs:[16]

| Front-harmonic | Neutral | Back-harmonic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front+neutral | Front | Neutral+front | Neutral+back | Back+neutral | Back | ||

| Close-mid-close | yöy | iey | iei | ieu | uoi | uou | |

| Close-open-close | yäi | yäy | iäy | uai | uau | ||

Olonets Karelian has only the triphthongs ieu, iey, iäy, uau, uou and yöy.[17]

Consonants

There are 18 consonants in Karelian:

| Labial | Alveolar | Lateral | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | voiceless | p /p/ | t /t/ | k /k/ | |||

| voiced | b /b/ | d /d/ | g /ɡ/ | ||||

| Affricate | č /tʃ/ | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | s /s/ | š /ʃ/ | h /h/ | |||

| voiced | v /v/ | z /z/ | ž /ʒ/ | ||||

| Nasal | m /m/ | n /n/ | |||||

| Liquid | r /r/ | l /l/ | |||||

| Approximant | j /j/ | ||||||

Two other consonant sounds; /f/ and /ts/ are found in loanwords.

Writing system

Alphabet

Karelian is today written using a Latin alphabet consisting of 29 characters. It extends the ISO basic Latin alphabet with the additional letters Č, Š, Ž, Ä, Ö and ʼ and excludes the letters Q, W and X.[18] This unified alphabet is used to write all Karelian varieties except Tver Karelian. The very few texts that were published in Karelian from medieval times through the 19th century used the Cyrillic alphabet. With the establishment of the Soviet Union, Finnish, written with the Latin alphabet, became official. However, from 1937–39 Karelian written in Cyrillic replaced Finnish as an official language of the Karelian ASSR (see "History" below).

Orthography

Karelian is written with orthography similar to Finnish orthography. However, some features of the Karelian language and thus orthography are different from Finnish:

- The Karelian system of sibilants is extensive; in Finnish, there is only one: /s/.

- Phonemic voicing occurs.

- Karelian retains palatalization, usually denoted with an apostrophe (e.g. d'uuri)

- The letter 'ü' may replace 'y' in some texts.

- The letter 'c' denotes /ts/, although 'ts' is used also. 'c' is more likely in Russian loan words.

| Sibilants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Letter | Alt. | IPA | Olonets Karelian | Karelian Proper | Finnish |

| č | ch | /tʃ/ | čoma, seiče | šoma, seičemen | soma, seitsemän |

| s | s | /s/ | se | že | se |

| š | sh | /ʃ/ | niškoi | niškoihin | niskoihin |

| z | z | /z/ | tazavaldu | tažavalda | tasavalta |

| ž | zh | /ʒ/ | kiža, liedžu | kiza, liedžu | kisa, lietsu |

Notice that /c/ and /č/ have length levels, which is not found in standard Finnish. For example, in Kalevala, Lönnrot's orthography metsä : metsän hides the fact that the pronunciation of the original material is actually /mettšä : metšän/, with palatalization of the affricate. The exact details depend on the dialect, though. See Yleiskielen ts:n murrevastineet.

Karelian actually uses /z/ as a voiced alveolar fricative. (In Finnish, z is a foreign spelling for /ts/.) The plosives /b/, /d/ and /ɡ/ may be voiced. (In most Finnish dialects, they are not differentiated from the unvoiced /p/, /t/, and /k/. Furthermore, in Karelian, voiced consonants occur also in native words, not just in loans as in standard Finnish.)

The sounds represented by č, š and ž are native to Karelian, but not Finnish. Speakers of Finnish do not distinguish /ʃ/ and /ʒ/ from /s/, nor /tʃ/ from /ts/ (medial) or /s/ (initial). For example, the native Karelian words kiza, šoma, liedžu and seičemen are kisa, soma, lietsu and seitsemän in standard Finnish.

History

Prehistory

As all other Finnic languages, Karelian descends from Proto-Finnic, which in turn ultimately descends from Proto-Uralic. The most recent ancestor of the Karelian dialects is the language variety spoken in the 9th century at the western shores of Lake Ladoga, known as Old Karelian (Finnish: muinaiskarjala).

Karelian is usually considered a part of the Eastern Finnic subgroup. It has been proposed that Late Proto-Finnic evolved into three dialects: Northern dialect, spoken in western Finland; Southern dialect, spoken in the area of modern-day Estonia and northern Latvia, and Eastern dialect, spoken in the regions east of the Southern dialect. In the 6th century, Eastern dialect arrived at the western shores of Lake Ladoga, and in the 9th century, Northern dialect reached the same region. These two dialects blended together and formed Old Karelian.[19]

Medieval period

By the end of the 13th century, speakers of Old Karelian had reached the Savo region in eastern Finland, increasingly mixing with population from western Finland. In 1323 Karelia was divided between Sweden and Novgorod according to the Treaty of Nöteborg, which started to slowly separate descendants of the Proto-Karelian language from each other. In the areas occupied by Sweden, Old Karelian started to develop into dialects of Finnish: Savonian dialects and Southeastern dialects.

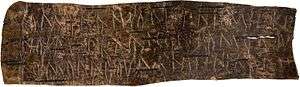

Birch bark letter no. 292 is the oldest known document in any Finnic language. The document is dated to the beginning of the 13th century. It was found in 1957 by a Soviet expedition, led by Artemiy Artsikhovskiy in the Nerev excavation on the left coast side of Novgorod.[20] The language used in the document is thought to be an archaic form of the language spoken in Olonets Karelia, a dialect of the Karelian language.[21]

In the regions ruled by Novgorod, the protolanguage started to evolve into Karelian language. In 1617 Novgorod lost parts of Karelia to Sweden in the Treaty of Stolbovo, which led the Karelian-speaking population of the occupied areas to flee from their homes. This gave rise to the Karelian speaking population in the Tver and Valday regions.[19]

19th century

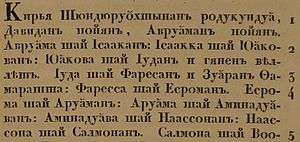

In the 19th century, a few books were published in Karelian using the Cyrillic script, notably A Translation of some Prayers and a Shortened Catechism into North Karelian and Olonets (Aunus) dialects in 1804, and the gospel of St. Matthew in South Karelian Tver dialect, in 1820. Karelian literature in 19th century Russia remained limited to a few primers, songbooks and leaflets.[22]

Soviet period

In 1921, the first all-Karelian congress under the Soviet regime debated whether Finnish or Karelian should be the official language (next to Russian) of the new "Karelian Labour Commune" (Карялан тыöкоммууни in Cyrillic Karelian, Karjalan Työkommuuni), which two years later would become the Karelian ASSR. In the end they chose Finnish. In 1931, a Karelian literary language using the Latin alphabet was standardized for the Tver Karelian community. From 1937–39 the Soviet government replaced Finnish in the Karelian ASSR with Karelian written in the Cyrillic alphabet.[22] During this period the newspaper Karjalan Sanomat was written in Karelian using Cyrillic, rather than in Finnish. The effort was dropped in 1940 and Finnish (written as always in the Latin alphabet) once again became official.[22]

In the 1980s, publishing began again in various adaptations of the Latin alphabet for Olonets Karelian and the White Sea and Tver dialects of Standard Karelian.

Recent events

In 2007 a standard alphabet was adopted to write all dialects.

In 2008, Joensuu University launched Finland's first Karelian language professorship, in order to save the language. A year later, Finland's first Karelian language nest (pre-school immersion group) was established in the town of Nurmes.[23]

Media in Karelian

- Oma Mua is published in Olonets Karelian.

- Vienan Karjala is published in North Karelian dialect.

- Karielan Šana is published in Tver Karelian dialect.

- Karjal Žurnualu – A monthly Karelian language journal published by Karjalan Kielen Seura in Finland.

- Yle Uudizet karjalakse – News articles and a weekly radio news program in Karelian are published by the Finnish Broadcasting Company.

Examples of Karelian dialects

North Karelian

A sample from the book Luemma vienankarjalaksi:

- Vanhat ihmiset sanottih, jotta joučen on ihmisestä tullun. Jouččenet aina ollah parittain. Kun yksi ammuttanneh, ni toini pitälti itköy toistah. Vain joučen oli pyhä lintu. Sitä ei nikonsa ruohittu ampuo, siitä tulou riähkä. Jouččenet tullah meilä kevyällä ta syksyllä tuas lähetäh jälelläh suvipuoleh. Hyö lennetäh suurissa parviloissa. Silloin kun hyö lähettih, ni se oli merkki, jotta talvi on lässä.[24]

- (Translation: Old people used to say that the swan is born of the man. Swans are always in pairs. When one is shot, other cries after another a long time. Yet swan is a sacred bird. Nobody ever dared to shoot them—it was a sin. Swans come to us in the spring and in the autumn they once again leave back to the south. They fly in large flocks. When they left, it was a sign that the winter is near.)

Olonets Karelian

Sample 1

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

- Kai rahvas roittahes vällinny da taza-arvozinnu omas arvos da oigevuksis. Jogahizele heis on annettu mieli da omatundo da heil vältämättäh pidäy olla keskenäh, kui vellil.[25]

- (English version: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.[26])

Sample 2

A sample from the book Karjalan kielen harjoituskogomus III–IV luokku Livvin murdehel. Note the older alphabet:

Olonets Karelian[27] Standard Finnish English translation Karjalas on čoma luondo. Korgiet koivut, Karjalassa on kaunis luonto. Korkeat koivut, There is beautiful nature in Karelia. Tall birches, vihandat kuuzet da pedäjät čomendetah meččiä. vihannat kuuset ja petäjät koristavat metsiä. green spruces and Scots pines decorate the forest. Joga kohtaine on täüzi muarjua da siendü. Joka paikka on täynnä marjaa ja sientä. Every place is full of berries and mushrooms. Kehtua vai kerätä! Järvet da jovetgi ollah kalakkahat: Kehtaa vain kerätä! Järvet ja joetkin ovat kalaisat: If only one picked them! The lakes and rivers, too, are full of fish: ongo haugii, lahnua, säüniä, matikkua, kuhua, siigua. on haukia, lahnoja, säyneitä, madetta, kuhaa, siikaa. there is pike, carp bream, ide, burbot, zander, whitefish. Ota ongiruagu da juokse järvele! Ota onkivapa ja juokse järvelle! Take a fishing rod and run to the lake!

Tver Karelian

A sample from the book Armaš šana:

- Puasinkoi on pieni karielan külä Tverin mualla. Šielä on nel'l'äkümmendä taluo. Šeizov külä joven rannalla. Jogi virduav hil'l'ah, žentän händä šanotah Tihvinča. Ümbäri on ülen šoma mua. – Tuatto šaneli: ammuin, monda šadua vuotta ennen, šinne tuldih Pohjois-Karielašta karielan rahvaš. Hüö leikkattih mečän i šeizatettih tämän külän. I nüt vielä küläššä šeizotah kojit, kumbazet on luaittu vanhašta mečäštä.[28]

- (Translation: Puasinkoi is a small Karelian village in the Tver region. There are forty houses. The village lies by a river. The river flows slowly—that's why it's called Tihvinitša. The surrounding region is very beautiful.—(My) father told (me): once, many hundreds of years ago, Karelians from North-Karelia came there. They cut down the forest and founded this village. And even now, there are houses in the village, which have been built from the trees of the old forest.)

See also

References

- ↑ Karelian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Change in the regulation by the president of Finland about European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, 27.11.2009 (in Finnish)

- 1 2 "Законодательные акты - Правительство Республики Карелия". gov.karelia.ru.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Karelian". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- 1 2 "Kotimaisten kielten tutkimuskeskus :: Karjalan kielet". Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ↑ "The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire – THE KARELIANS". Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-11-11. Retrieved 2009-11-02.

- ↑ Burtsoff, Ari. "Karjalaa osaavien yhteisö on suuri".

- 1 2 "ELDIA project - Karelian". Archived from the original on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ↑ "Koulunjohtaja Paavo Harakka - Esitelmä valtakunnallisilla kotiseutupäivillä". Archived from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ↑ "The Karelian Language and Tver Karelian Cultural Autonomy". Retrieved 2010-07-31.

- ↑ "FINLEX - Asetus alueellisia kieliä tai vähemmistökieliä koskevan eurooppalaisen peruskirjan voimaansaattamisesta". Retrieved 2010-06-06.

- ↑ "Karjala - kieli, murre ja paikka". Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ↑ "Mauri Rastas: "karjalan kieli"". Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ↑ "Itämerensuomalaisten kielten äänteellisiä ominaispiirteitä". Archived from the original on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2011-03-02.

- 1 2 П.М. Зайков. Грамматика карельского языка. Петрозаводск: Периодика, 1999

- 1 2 "Vokalit". Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ↑ "Government of Karelia approved uniform Karelian language alphabet". Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- 1 2 "Selityksiä ja lisätietoja". Retrieved 2011-02-07.

- ↑ Арциховский, А.В.; Борковский, В.И. (1963). Новгородские грамоты на бересте (из раскопок 1956–1957 гг.) (in Russian). Из-во Акад. Наук СССР.

- ↑ Itämerensuomalaista kirjoitusta 1200-luvulta Archived 2012-05-25 at Archive.is (in Finnish)

- 1 2 3 Rein Taagepera, The Finno-Ugric republics and the Russian state, p.111

- ↑ "Nurmeksen kielipesässä lapsista tulee karjalankielisiä". Archived from the original on 2012-01-15. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ↑ "Kotimaisten kielten tutkimuskeskus :: Viena". Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2010-08-06.

- ↑ "Ristikanzan oigevuksien yhtehine deklaratsii" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-05-15.

- ↑ "Universal Declaration of Human Rights". Retrieved 2010-06-01.

- ↑ Bogdanova, Leena; Ščerbakova, Tamara. Karjalan kielen harjoituskogomus III–IV luokku Livvin murdehel. Petroskoi «Periodika», 2004, p. 14.

- ↑ "Kotimaisten kielten tutkimuskeskus :: Tverinkarjala". Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2010-08-06.

Sources

- Ahtia, E. V. (1938): Karjalan kielioppi: Äänne- ja sanaoppi. Suojärvi: Karjalan kansallisseura.

- Ahtia, Edvard V. (2014): Karjalan kielioppi II: Johto-oppi. Joensuu: Karjalan Kielen Seura. ISBN 978-952-5790-42-9.

- Ahtia, Edvard V. (2014): Karjalan kielioppi III: Lauseoppi. Joensuu: Karjalan Kielen Seura. ISBN 978-952-5790-39-9.

- Ojansuu, Heikki (1918): Karjala-aunuksen äännehistoria. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran toimituksia 162.

- Virtaranta, Pertti; Koponen, Raija (eds) (1968-2005): Karjalan kielen sanakirja. Helsinki: Kotimaisten kielten tutkimuskeskus / Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura.

External links

| Karelian language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

- The Peoples of the Red Book: THE KARELIANS

- Karjalaine lehüt - Karelian page

- Neuvostoliiton kielipolitiikkaa: Karjalan kirjakielen suunnittelu 1930-luvulla ("On Soviet language policy: The planning of the Karelian literary language in the 1930's", in Finnish)

- Karjalan kirjakielestä (in Finnish)

- Livgiläižet (in Russian)

- Karelian language on Omniglot

- Karjalan kirjaimet (in Karelian)

- Karjalan kielioppi (in Karelian)

- Грамматика карельского языка

- УРОКИ КАРЕЛЬСКОГО ЯЗЫКА - Karelian lessons (in Russian)

- A short Karelian Conversation

- Karelian-Russian-Finnish dictionary

- Karelian-Finnish dictionary (Note: č is categorized under tš)

- Karelian-Vepsian-Finnish-Estonian dictionary

- Karjalan kielen harjoituskogomus (PDF/in Karelian)