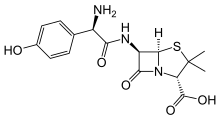

Amoxicillin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /əˌmɒksɪˈsɪlɪn/ |

| Trade names | Hundreds of names[1] |

| Synonyms | amox, amoxycillin (AAN AU) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a685001 |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous |

| Drug class | β-lactam antibiotic |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 95% by mouth |

| Metabolism | less than 30% biotransformed in liver |

| Elimination half-life | 61.3 minutes |

| Excretion | Kidneys |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard |

100.043.625 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C16H19N3O5S |

| Molar mass | 365.4 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.6±0.1 [2] g/cm3 |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Amoxicillin, also spelled amoxycillin, is an antibiotic useful for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections.[3] It is the first line treatment for middle ear infections.[3] It may also be used for strep throat, pneumonia, skin infections, and urinary tract infections among others.[3] It is taken by mouth, or less commonly by injection.[3][4]

Common side effects include nausea and rash.[3] It may also increase the risk of yeast infections and, when used in combination with clavulanic acid, diarrhea.[5] It should not be used in those who are allergic to penicillin.[3] While usable in those with kidney problems, the dose may need to be decreased.[3] Its use in pregnancy and breastfeeding does not appear to be harmful.[3] Amoxicillin is in the beta-lactam family of antibiotics.[3]

Amoxicillin was discovered in 1958 and came into medical use in 1972.[6][7] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[8] It is one of the most commonly prescribed antibiotics in children.[9] Amoxicillin is available as a generic medication.[3] It has a wholesale cost in the developing world of between 0.02 and 0.05 USD per pill.[10] In the United States, ten days of treatment costs about 16 USD (0.40 USD per pill).[3]

Medical uses

Amoxicillin is used in the treatment of a number of infections, including acute otitis media, streptococcal pharyngitis, pneumonia, skin infections, urinary tract infections, Salmonella infections, Lyme disease, and chlamydia infections.[3][11]

Respiratory infections

Amoxicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanate have been recommended by guidelines as the drug of choice for bacterial sinusitis and other respiratory infections.[11] Most sinusitis infections are caused by viruses, for which amoxicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanate are ineffective,[12] and the small benefit gained by Amoxicillin may be overridden by the adverse effects.[13] Amoxicillin is recommended as the preferred first-line treatment for community-acquired pneumonia in adults by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, either alone (mild to moderate severity disease) or in combination with a macrolide.[14] The World Health Organization recommends amoxicillin as first-line treatment for pneumonia that is not "severe".[15] Amoxicillin is used in post-exposure inhalation of anthrax to prevent disease progression and for prophylaxis.[11]

H. pylori

It is effective in the treatment of stomach infections of Helicobacter pylori. When used to treat H. pylori infection it is combined with lansoprazole, clarithromycin, omeprazole and others in varying amounts and dosage schedules. It is also used to treat Lyme disease in children under eight-years old.[11]

Skin infections

Amoxicillin is occasionally used for the treatment of skin infections,[11] such as acne vulgaris.[16] It is often an effective treatment for cases of acne vulgaris that have responded poorly to other antibiotics, such as doxycycline and minocycline.[17]

Infections in infants in resource-limited settings

Amoxicillin is recommended by the World Health Organization for the treatment of infants with signs and symptoms of pneumonia in resource-limited situations when the parents are unable or unwilling to accept hospitalization of the child. Amoxicillin in combination with gentamicin is recommended for the treatment of infants with signs of other severe infections when hospitalization is not an option.[18]

Prevention of bacterial endocarditis

It is also used to prevent bacterial endocarditis in high-risk people having dental work done, to prevent Streptococcus pneumoniae and other encapsulated bacterial infections in those without spleens, such as people with sickle-cell disease, and for both the prevention and the treatment of anthrax.[3] The United Kingdom recommends against its use for infectious endocarditis prophylaxis.[19] These recommendations do not appear to have changed the rates of infection for infectious endocarditis.[20]

Combination treatment

Amoxicillin is susceptible to degradation by β-lactamase-producing bacteria, which are resistant to most β-lactam antibiotics, such as penicillin. For this reason, it may be combined with clavulanic acid, a β-lactamase inhibitor. This drug combination is commonly called co-amoxiclav.[21]

Spectrum of activity

It is a moderate-spectrum, bacteriolytic, β-lactam antibiotic in the aminopenicillin family used to treat susceptible Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. It is usually the drug of choice within the class because it is better-absorbed, following oral administration, than other β-lactam antibiotics. In general, Streptococcus, Bacillus subtilis, Enterococcus, Haemophilus, Helicobacter, and Moraxella are susceptible to amoxicillin, whereas Citrobacter, Klebsiella and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are resistant to it.[22] Some E. coli and most clinical strains of Staphylococcus aureus have developed resistance to amoxicillin to varying degrees.

Adverse effects

Side effects are similar to those for other β-lactam antibiotics, including nausea, vomiting, rashes, and antibiotic-associated colitis. Loose bowel movements (diarrhea) may also occur. Rarer side effects include mental changes, lightheadedness, insomnia, confusion, anxiety, sensitivity to lights and sounds, and unclear thinking. Immediate medical care is required upon the first signs of these side effects.

The onset of an allergic reaction to amoxicillin can be very sudden and intense; emergency medical attention must be sought as quickly as possible. The initial phase of such a reaction often starts with a change in mental state, skin rash with intense itching (often beginning in fingertips and around groin area and rapidly spreading), and sensations of fever, nausea, and vomiting. Any other symptoms that seem even remotely suspicious must be taken very seriously. However, more mild allergy symptoms, such as a rash, can occur at any time during treatment, even up to a week after treatment has ceased. For some people allergic to amoxicillin, the side effects can be fatal due to anaphylaxis.

Use of the amoxicillin/clavulanic acid combination for more than one week has caused mild hepatitis in some patients. Young children having ingested acute overdoses of amoxicillin manifested lethargy, vomiting, and renal dysfunction.[23][24]

Nonallergic rash

Between 3 and 10% of children taking amoxicillin (or ampicillin) show a late-developing (>72 hours after beginning medication and having never taken penicillin-like medication previously) rash, which is sometimes referred to as the "amoxicillin rash". The rash can also occur in adults.

The rash is described as maculopapular or morbilliform (measles-like; therefore, in medical literature, it is called "amoxicillin-induced morbilliform rash".[25]). It starts on the trunk and can spread from there. This rash is unlikely to be a true allergic reaction and is not a contraindication for future amoxicillin usage, nor should the current regimen necessarily be stopped. However, this common amoxicillin rash and a dangerous allergic reaction cannot easily be distinguished by inexperienced persons, so a healthcare professional is often required to distinguish between the two.[26][27]

A nonallergic amoxicillin rash may also be an indicator of infectious mononucleosis. Some studies indicate about 80-90% of patients with acute Epstein Barr virus infection treated with amoxicillin or ampicillin develop such a rash.[28]

- Nonallergic amoxicillin rash eight days after first dose: This photo was taken 24 hours after the rash began.

- Eight hours after the first photo, individual spots have grown and begun to merge.

- At 23 hours after the first photo, the color appears to be fading, and much of rash has spread to confluence.

Interactions

Amoxicillin may interact with these drugs:

- Anticoagulants (dabigatran, warfarin).[29][11]

- Cancer treatment (methotrexate).

- Uricosuric drugs.

- Typhoid vaccine[30]

- Probenecid reduces renal excretion and increases the blood levels of amoxicillin.

- Oral contraceptives may become less effective.

- Allopurinol (gout treatment).

- Endocarditis prevention.[11]

Pharmacology

Amoxicillin diffuses easily into tissues and body fluids. Penetration into the central nervous system increases in meningitis. It will cross the placenta and is excreted into breastmilk in small quantities. It is excreted into the urine and metabolized by the liver. It has an onset of 30 minutes and a half-life of 3.7 hours in newborns and 1.4 hours in adults.[11]

Amoxicillin attaches to the cell wall of susceptible bacteria and results in their death. It also is a bactericidal compound. It is effective against Streptococci, Pneumococci, Enterococci, Haemophilus influenzae, Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, Neisseria meningitidis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Shigella, Chlamydia trachomatis, Salmonell, Borrelia burgdorferi and Helicobactor pylori.[11] As a derivative of ampicillin, amoxicillin is a member of the same family as penicillins and like them, is a β-lactam antibiotic.[31] It inhibits cross-linkage between the linear peptidoglycan polymer chains that make up a major component of the cell wall of Gram-positive and a minor component of Gram-negative bacteria. Gram negative bacteria are not generally susceptible to Beta-lactam antibiotics. It has two ionizable groups in the physiological range (the amino group in alpha-position to the amide carbonyl group and the carboxyl group).

History

Amoxicillin was one of several semisynthetic derivatives of 6-aminopenicillanic acid (6-APA) developed at Beecham, England in the 1960s. It became available in 1972 and was the second aminopenicillin to reach the market (after ampicillin in 1961).[32][33][34] Co-amoxiclav became available in 1981.[33]

Society and culture

Modes of delivery

Pharmaceutical manufacturers make amoxicillin in trihydrate form, for oral use available as capsules, regular, chewable and dispersible tablets, syrup and pediatric suspension for oral use, and as the sodium salt for intravenous administration. Amoxicillin is most commonly taken orally. The liquid forms are helpful where the patient might find it difficult to take tablets or capsules. The intravenous form is not sold in the US; in the US when amoxicillin is needed intravenously, it is usually accomplished by adding amoxicillin powder to bags of saline solution. There are small saline bags that have a screw off cap on the top of them to allow the powder to be added, commonly called piggy back bags by medical staff. Powdered Amoxicillin can be mixed with saline solution or sterile water to be used in a syringe, but because of the slow delivery time that is needed to inject the solution (3–4 minutes for solution containing 1g of amoxicillin powder) this method is seldom used. Ampicillin can also be used instead of amoxicillin when person can't swallow and needs antibiotics as it has the same spectrum as amoxicillin.

Research with mice indicated successful delivery using intraperitoneally injected amoxicillin-bearing microparticles.[35]

Names

"Amoxicillin" is the INN, BAN, and USAN, while "amoxycillin" is the AAN.

Amoxicillin is one of the semisynthetic penicillins discovered by Beecham scientists. The patent for amoxicillin has expired, thus amoxicillin and co-amoxiclav preparations are marketed under various trade names across the world.[1]

References

- 1 2 "International brand names for amoxicillin". www.drugs.com. Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ↑ "Amoxycillin_msds".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Amoxicillin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ↑ "Amoxicillin Sodium for Injection". EMC. 10 February 2016. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ↑ Gillies, M; Ranakusuma, A; Hoffmann, T; Thorning, S; McGuire, T; Glasziou, P; Del Mar, C (17 November 2014). "Common harms from amoxicillin: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials for any indication". CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal. 187 (1): E21–31. doi:10.1503/cmaj.140848. PMC 4284189. PMID 25404399.

- ↑ Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 490. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ Roy, Jiben (2012). An introduction to pharmaceutical sciences production, chemistry, techniques and technology. Cambridge: Woodhead Pub. p. 239. ISBN 9781908818041. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Kelly, Deirdre (2008). Diseases of the liver and biliary system in children (3 ed.). Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 217. ISBN 9781444300543. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ "Amoxicillin". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Amoxicillin" (PDF). Davis. 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 8, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ↑ American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question" (PDF). Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ↑ Ahovuo-Saloranta, A.; Rautakorpi, U. M.; Borisenko, O. V.; Liira, H.; Williams Jr, J. W.; Mäkelä, M. (2014). Ahovuo-Saloranta, Anneli, ed. "Antibiotics for acute maxillary sinusitis". The Cochrane Library (2): CD000243. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000243.pub3. PMID 24515610.

- ↑ "Pneumonia - National Library of Medicine - PubMed Health". Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ "Revised WHO Classification and Treatment of Pneumonia in Children at Health Facilities - NCBI Bookshelf". Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ "Adolescent Acne: Management". Archived from the original on 2010-12-22.

- ↑ "Amoxicillin and Acne Vulgaris". scienceofacne.com. 2012-09-05. Archived from the original on 2012-07-21. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ↑ "Guideline: Managing Possible Serious Bacterial Infection in Young Infants When Referral Is Not Feasible - NCBI Bookshelf". Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ "CG64 Prophylaxis against infective endocarditis: Full guidance" (PDF). NICE. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ↑ Thornhill, MH; Dayer, MJ; Forde, JM; Corey, GR; Chu, VH; Couper, DJ; Lockhart, PB (2011-05-03). "Impact of the NICE guideline recommending cessation of antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of infective endocarditis: before and after study". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 342: d2392. doi:10.1136/bmj.d2392. PMC 3086390. PMID 21540258.

- ↑ "Amoxicillin Susceptibility and Resistance Data" (PDF). Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ "Amoxicillin spectrum of bacterial susceptibility and Resistance" (PDF). Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ↑ Cundiff j, Joe S.; Joe, S (2007). "Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid-induced hepatitis". Am. J. Otolaryngol. 28 (1): 28–30. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2006.06.007. PMID 17162128.

- ↑ R. Baselt (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 81–83.

- ↑ "Role of delayed cellular hypersensitivity and adhesion molecules in amoxicillin-induced morbilliform rashes". Cat.inist.fr. Archived from the original on 2011-12-29. Retrieved 2010-11-13.

- ↑ Pichichero ME (April 2005). "A review of evidence supporting the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation for prescribing cephalosporin antibiotics for penicillin-allergic patients". Pediatrics. 115 (4): 1048–57. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-1276. PMID 15805383. Archived from the original on 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Schmitt, Barton D. (2005). Your child's health: the parents' one-stop reference guide to symptoms, emergencies, common illnesses, behavior problems, healthy development (2nd ed.). New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-38369-0.

- ↑ Kagan, B (1977). "Ampicillin rash". Western Journal of Medicine. 126 (4): 333–335. PMC 1237570. PMID 855325.

- ↑ British National Formulary 57 March 2009

- ↑ Arcangelo, Virginia Poole; Peterson, Andrew M.; Wilbur, Veronica; Reinhold, Jennifer A. (August 17, 2016). Pharmacotherapeutics for Advanced Practice: A Practical Approach. LWW. ISBN 978-1-496-31996-8.

- ↑ Alcamo, I. Edward (2003), Microbes and Society: An Introduction to Microbiology, Jones & Bartlett Learning, p. 198, ISBN 9780763714307, archived from the original on 2016-12-23.

- ↑ Geddes, AM; et al. (Dec 2007). "Introduction: historical perspective and development of amoxicillin/clavulanate". Int J Antimicrob Agents. 30 (Suppl 2): S109–12. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.07.015. PMID 17900874.

- 1 2 Raviña, E (2014). The Evolution of Drug Discovery. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. p. 262. ISBN 9783527326693.

- ↑ Bruggink, A (2001). Synthesis of β-lactam antibiotics. Springer. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7923-7060-4.

- ↑ Farazuddin, Mohammad; Chauhan, Arun; Khan, Raza M.M.; Owais, Mohammad (2011). "Amoxicillin-bearing microparticles: potential in the treatment of Listeria monocytogenes infection in Swiss albino mice". Bioscience Reports. 31 (4): 265–72. doi:10.1042/BSR20100027. PMID 20687896.

Further reading

- Neal, M. J. (2002). Medical pharmacology at a glance (4th ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 978-0-632-05244-8.

- British National Formulary 45 March 2003