Battle of Kupres (1994)

| Battle of Kupres | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Bosnian War | |||||||

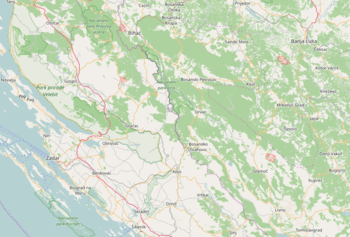

Map of Operations Autumn-94 and Cincar | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

3.130 initially[1] 8.600 finally[2] |

1.000 initially[3] 2.600 finally[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

ARBiH: 41 killed, 162 wounded; HVO: 4 killed, 15 wounded | Unknown | ||||||

The Battle of Kupres (Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian: Bitka za Kupres) was a battle of the Bosnian War, fought between the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH) and the Croatian Defence Council (HVO) on one side and the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) on the other from 20 October to 3 November 1994. It marks the first tangible evidence of the Bosniak–Croat alliance set out in the Washington Agreement of March 1994, brokered by the United States to end the Croat–Bosniak War fought between the ARBiH and the HVO in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The ARBiH and the HVO were not coordinated at first, rather they launched separate operations aimed at capture of Kupres.

The ARBiH offensive, codenamed Autumn-94 (Jesen-94), started on 20 October, with the primary aim of advancing from Bugojno towards VRS-held Donji Vakuf, supported by a secondary attack towards Kupres aimed at disruption of the VRS defences and threatening a supply route to Donji Vakuf. The primary attacking force soon ground to a halt, shifting the focus of the operation to Kupres, where substantial reinforcements were deployed to ensure a gradual advance of the ARBiH. On 29 October, the HVO decided to attack, as it considered the ARBiH had directly threatened the strategic Kupres plateau. The HVO launched its offensive, codenamed Operation Cincar (Operacija Cincar), on 1 November. Following a brief lull in the ARBiH advance, thought to be brought on by a variety of causes and a direct request by the President of Bosnia and Herzegovina Alija Izetbegović to the ARBiH to cooperate with the HVO, commanding officers of the two forces met to coordinate their operations for the first time since the Washington Agreement. Kupres itself was captured by the HVO on 3 November 1994.

Besides the political significance of the battle for future developments of the war in Bosnia, the battle was militarily significant for planning and execution of Operation Winter '94 by the Croatian Army (HV) and the HVO aimed at relieving the siege of Bihać in late November and December 1994. Territorial gains made by the HVO and the ARBiH in the Battle of Kupres safeguarded the right flank of Operation Winter '94.

Background

The 1990 revolt of the Croatian Serbs was centered on the predominantly Serb-populated areas of the Dalmatian hinterland around the city of Knin,[5] parts of Lika, Kordun, Banovina regions and in eastern Croatian settlements with significant Serb populations.[6] These areas were subsequently named the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK). The RSK declared its intention of political integration with Serbia and was viewed by the Government of Croatia as a rebellion.[7] By March 1991, the conflict escalated to war—the Croatian War of Independence.[8] In June 1991, Croatia declared its independence as Yugoslavia disintegrated,[9] followed by a three-month moratorium on the decision,[10] thus the decision came into effect on 8 October.[11] A campaign of ethnic cleansing was then initiated by the RSK against Croatian civilians and most non-Serbs were expelled by early 1993. By November 1993, less than 400 and 1,500–2,000 ethnic Croats remained in UN protected areas Sector South[12] and Sector North respectively.[13]

As the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) increasingly supported the RSK and the Croatian police was unable to cope with the situation, the Croatian National Guard (ZNG) was formed in May 1991. The ZNG was renamed the Croatian Army (HV) in November.[14] The establishment of the military of Croatia was hampered by a United Nations (UN) arms embargo introduced in September.[15] The final months of 1991 saw the fiercest fighting of the war, culminating in the Battle of the barracks,[16] the Siege of Dubrovnik,[17] and the Battle of Vukovar.[18]

In January 1992, the Sarajevo Agreement was signed by representatives of Croatia, the JNA and the UN, and fighting between the two sides paused.[19] Ending the series of unsuccessful ceasefires, United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) was deployed to Croatia to supervise and maintain the agreement.[20] The conflict largely passed on to entrenched positions, and the JNA soon retreated from Croatia into Bosnia and Herzegovina, where a new conflict was anticipated,[19] but Serbia continued to support the RSK.[21] HV advances restored small areas to Croatian control—as the siege of Dubrovnik was lifted,[22] and in Operation Maslenica.[23] Croatian towns and villages were intermittently attacked by artillery,[24] or missiles.[6][25]

As the JNA disengaged in Croatia, its personnel prepared to set up a new Bosnian Serb army, as Bosnian Serbs declared the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina on 9 January 1992, ahead of the 29 February – 1 March 1992 referendum on independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina—which would later be cited as a pretext for the Bosnian War.[26] Bosnian Serbs set up barricades in the capital, Sarajevo and elsewhere on 1 March, and the next day the first fatalities of the war were recorded in Sarajevo and Doboj. In the final days of March, the Bosnian Serb army started artillery attacks on Bosanski Brod, and the HV 108th Brigade crossed the border adjacent to the town in reply.[27] On 4 April, Serb artillery began shelling Sarajevo.[28] Even though the war originally pitted Bosnian Serbs against non-Serbs in the country, it evolved into a three-sided conflict by the end of the year, as the Croat–Bosniak War started.[29] By that time, the Bosnian Serb army—renamed Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) after the Republika Srpska state proclaimed in the Bosnian Serb-held territory—controlled about 70% of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[30] That proportion would not change significantly over the next two years.[31] Republika Srpska was involved in the Croatian War of Independence in a limited capacity, through military and other aid to the RSK, occasional air raids launched from Banja Luka, and most significantly through artillery attacks against urban centres.[32][33]

Prelude

Following a new military strategy of the United States endorsed by Bill Clinton since February 1993,[34] the Washington Agreement was signed by Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina in March 1994. The agreement ended the Croat–Bosniak War[35] and established the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[36] The political settlement allowed the ARBiH and the HVO to deploy additional troops against the VRS in a series of small-scale attacks designed to wear down the Bosnian Serb military, but the attacks claimed no territorial gains before October.[37] The ARBiH adopted an attrition warfare strategy relying on its numerical superiority compared to the VRS, which suffered from manpower shortages. This strategy aimed for limited advances, without support of heavy weapons and means of transport—unavailable to the ARBiH at the time.[38]

In March–November 1994, the ARBiH conducted a series of attacks with relatively limited objectives, attacking the VRS at the Vlašić Mountain, the Stolice Peak of the Majevica Mountain and Donji Vakuf, as well as in the area between Tešanj and Teslić, near Brčko, Kladanj, Sarajevo, on the Bjelašnica and the Treskavica Mountain, Gračanica, Vareš, Konjic and Doboj. Further efforts were made, together with the HVO, against the VRS near Nevesinje in September–November, but most of the offensives made little or no gains. At the same time, VRS attacks north of Sarajevo were successfully repulsed.[39] It was hoped by the ARBiH General Staff that the VRS could not muster sufficient reserves to hold off the simultaneous, relatively limited attacks.[40] Little territory changed hands as a result of the ARBiH offensive by the end of October, but the VRS shortage of troops worsened.[37]

Kupres was of interest to the ARBiH and the HVO, albeit for different reasons. The HVO wanted to reverse April 1992 loss of the town, home to a significant Croat community before the war, and to control the Tomislavgrad–Bugojno–Šipovo road. The ARBiH advance towards Kupres was planned as a secondary axis of its offensive towards Donji Vakuf, 20 kilometres (12 miles) to the northwest, codenamed Autumn-94.[41] The ARBiH wanted to deny the VRS a supply route passing through Kupres in order to weaken VRS defence around Donji Vakuf.[42]

It is not clear how the ARBiH and the HVO coordinated before their advance to Kupres. Most probably, the two forces' commands agreed on a simultaneous offensive against Kupres, without revealing actual battle plans to their counterparts. The HVO's contribution in the offensive, codenamed Operation Cincar, was planned jointly by the HVO and the HV.[43]

Order of battle

Initially, the ARBiH committed 3,130 troops to its secondary axis—the thrust towards Kupres.[44] They were organized with the 370th Mountain Infantry Brigade on the right flank of the 14-kilometre (8.7 mi) front manned by the ARBiH 7th Corps southwest of Bugojno, and the 307th Mountain Infantry Brigade on the left flank of the ARBiH effort.[45] In the primary attack axis zone, the ARBiH grouped about 5,600 additional troops, facing an estimated 4,800 VRS soldiers around Donji Vakuf. Kupres itself and the surrounding plateau were defended by approximately 2,600 VRS troops,[3] assigned to the 7th Motorized Infantry Brigade of the 2nd Krajina Corps,[46] supported by corps-level artillery and armour.[47] Around 1,000 troops were nominally facing the ARBiH units,[3] whereas the rest guarded the heights towards the HVO. On the eve of the attack, some 450-600 troops manned the lines attacked by the ARBiH.[3] The bulk of the HVO force consisted of troops contributed by the 1st, the 2nd and the 3rd Guards Brigades, supported by the Bosnian Croat special police and the 60th Guards Airborne Battalion "Ludvig Pavlović". Although participation of the HV in the battle was denied by Croatia, it is thought to have likely occurred.[43] Specifically, the 1st Croatian Guards Brigade is thought to have taken part in the battle,[48] and Bosnian Croat reports pertaining to the battle specify the Zrinski Battalion of the brigade as taking part in the operation.[49] The ARBiH 7th Corps was commanded by Brigadier General Mehmed Alagić, while the HVO Tomislavgrad Corps, formally in control of Operation Cincar, was commanded by Colonel Josip Černi.[50] The VRS 2nd Krajina Corps was under command of General Grujo Borić.[51]

| Corps | Unit | Note |

|---|---|---|

| 7th Corps | 307th Mountain Infantry Brigade | Initial deployment[45] |

| 370th Mountain Infantry Brigade | Initial deployment[45] | |

| 317th Mountain Infantry Brigade | Added on 20 October[52] | |

| 305th Mountain Infantry Brigade | Elements added on 21 October[53] | |

| 37th Light Infantry Brigade | Added on 27 October[54] | |

| 27th Mountain Infantry Brigade | Elements added on 27 October[55] | |

| 1 battalion of the 7th Mountain Infantry Brigade | Conscript unit, added on 27 October[55] | |

| General Staff Guards Brigade | Added on 28 October[56] |

| Corps | Unit | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Tomislavgrad Corps | 1st Guards Brigade "Ante Bruno Bušić" | |

| 2nd Guards Brigade | ||

| 3rd Guards Brigade | ||

| 60th Guards Ariborne Battalion "Ludvig Pavlović" | ||

| 1st Home Guard Regiment | Elements only, HQ Posušje[49] | |

| 79th Home Guard Regiment "King Tomislav" | Elements only, HQ Tomislavgrad[49] | |

| 80th Home Guard Regiment "Petar Krešimir IV" | Elements only, HQ Livno[49] | |

| Special police | Bosnian Croat Ministry of Interior unit | |

| 1st Croatian Guards Brigade | (Croatian Army)[48][49] |

| Corps | Unit | Note |

|---|---|---|

| 2nd Krajina Corps | 7th Motorized Infantry Brigade | |

| Corps level artillery and armour | reinforcing the 7th Brigade[47] | |

| Mixed reconnaissance unit | two platoons from 2nd Krajina corps command[57] | |

| 5. Glamoč brigade | one company and elements from one battalion[57] | |

| 9. Grahovo light brigade | one company[57] | |

| 1st Krajina Corps | Civilian police battalion | from Banja Luka[57] |

| 1. light brigade Banja Luka | one battalion[57] | |

| 3rd Corps | "Panthers" brigade | elements only[57] |

Timeline

October

The ARBiH launched the secondary axis of Operation Autumn-94—drive towards Kupres—at 2 am on 20 October,[42] hours after the primary attacking force started moving against Donji Vakuf.[58] As the primary effort of the ARBiH offensive bogged down the same day, Kupres became the main objective. The 317th Mountain Infantry Brigade was added to augment the ARBiH force that made initial advances towards Kupres.[52] The next day, as the ARBiH gradually advanced, elements of the 305th Mountain Brigade were also sent as reinforcements to the attacking force.[53] By 23 October, the ARBiH moved close enough to Kupres to direct heavy mortar fire against the town.[42] On 25 October, the ARBiH 7th Corps requested a meeting with the HVO Tomislavgrad Corps representatives to coordinate further advances in the area, however the HVO postponed the meeting until after 28 October due to replacement of the Tomislavgrad Corps commanding officer.[59] On 27 October, the ARBiH 37th Light Infantry Brigade was added to the attack,[54] slowly progressing from one mountain ridge to the next.[42] In addition, elements of the 27th Mountain Infantry Brigade and a battalion of the 7th Conscripted Mountain Infantry Brigade joined the ARBiH push.[55] On 28 November, the ARBiH General Staff committed a guards brigade attached to the General Staff to the battle.[56]

Since the beginning of the ARBiH offensive, the HVO had been assembling three of its four guards brigades under command of General Ante Roso, as well as other supporting units, including the 60th Guards Airborne Battalion.[43] On 29 October, the Ministry of Defence of the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia and the HVO General Staff met and decided to launch Operation Cincar to capture the town of Kupres. The decision was reportedly motivated by a desire to consolidate territory controlled by the HVO around Kupres and by the strategic importance of the Kupres plateau, which commanded the northern approaches to the HVO-held Livanjsko field. The operation was originally scheduled for 31 October at 4:30 am, only to be postponed by 24 hours, as the HVO needed more time to prepare. Delayed arrival of reconnaissance teams further postponed the HVO offensive until 8 am on 1 November 1994.[49]

November

The HVO advanced north along two main axes of attack. The western axis advanced from Šuica along the main road towards Kupres, capturing the village of Donji Malovan on 1 November. The eastern axis of the HVO offensive moved from Ravno towards Rilić. Just as the HVO began to move north, the ARBiH suspended its westward advance. Various explanations for the pause were put forward, including fog, rain, need to secure territorial gains, wear of equipment and fatigue of personnel.[60] Regardless, that day the President of Bosnia and Herzegovina Alija Izetbegović telephoned Alagić requesting an adequate level of cooperation and avoidance of any conflicts with the HVO.[61] Finally, Alagić made a public call to the HVO to participate in the offensive against the VRS in Kupres.[62] The same day, the VRS targeted Bugojno using two 9K52 Luna-M missiles.[48]

On 2 November, the HVO captured Gornji Malovan and Rilić, while the Serb civilian population started to evacuate from Kupres.[43] Alagić visited the HVO Tomislavgrad Corps headquarters to discuss cooperation, but refused to discuss the matter, citing inadequate officers present there, and proposed a new meeting at 11 pm that day at the ARBiH 317th Brigade headquarters in Gornji Vakuf.[63] The Chief of the HVO General Staff, Major General Tihomir Blaškić made a written apology on behalf of the HVO claiming the HVO officers had to be elsewhere at the time.[64] A new meeting took place as proposed by Alagić. The meeting concluded at 3 am, with an agreement between Alagić and Černi to withdraw some of the ARBiH troops on the right flank of the HVO thrust to allow the HVO to strike Kupres from that direction, and coordinate their further advances beyond Kupres.[63] Although cooperation was established, there was no joint command of the ARBiH and the HVO.[62]

The ARBiH pullback was completed by 11 am on 3 November, while the right flank of the ARBiH force pressed forward to capture the Kupreška Vrata Pass,[65] 3 kilometres (1.9 miles) away from Kupres. The Bosnian Croat special police and the 60th Guards Airborne Battalion entered Kupres shortly after noon,[43] and the HVO completed capture of the town by 1:30 pm.[66] The HVO proceeded to capture nearly the entire Kupres plateau, bringing the 1st, the 79th and the 80th Home Guards Regiments of the HVO to hold defensive positions on the plateau.[49] The VRS was unable to counter-attack in a timely manner, because it had no reserves in place for the task.[67]

Aftermath

The ARBiH significantly shortened its positions held opposite the VRS and captured 130 square kilometres (50 square miles) of territory,[68] while the HVO captured nearly 400 square kilometres (150 square miles) of the area around Kupres.[69] Battle losses of the ARBiH amounted to 41 killed in action and 162 wounded troops.[68] By 3 November, 4 HVO troops were killed and 15 wounded,[66] and further 3 soldiers died and 5 were wounded in a VRS counter-attack near Zlosela at 11 am on 4 November.[49]

The Battle of Kupres was the first concrete result of the renewed Bosniak–Croat alliance in the Bosnian War,[70] and the advance to Kupres was the first military effort coordinated between the ARBiH and the HVO since the Washington Agreement.[60][71] Following the victory, morale of the ARBiH and the HVO soared. Further advantages for them were the recapture of initiative from the VRS and full control of the Split–Livno–Kupres–Bugojno road, allowing improved logistics of the ARBiH and the HVO in the area, as well as greater volume of transport of arms and ammunition,[68] especially after the United States unilaterally ended the arms embargo against Bosnia and Herzegovina in November 1994.[72] The move in effect allowed the HV to supply itself as the arms shipments flowed through Croatia.[36] Finally, the outcome of the Battle of Kupres secured the right flank of the Livanjsko field, which became especially significant later that month when Operation Winter '94 was launched by the HV and the HVO northwest of Livno in order to draw off a part of the force besieging Bihać and prevent capture of Bihać by the VRS.[35] The battle is considered to be a significant contribution to subsequent success of the HV in the Croatian War of Independence and the Bosnian War.[73]

Footnotes

- ↑ Ramić 2004, pp. 92

- ↑ Ramić 2004, pp. 133

- 1 2 3 4 Marić 2017, pp. 99

- ↑ Marić 2017, pp. 123

- ↑ The New York Times & 19 August 1990

- 1 2 ICTY & 12 June 2007

- ↑ The New York Times & 2 April 1991

- ↑ The New York Times & 3 March 1991

- ↑ The New York Times & 26 June 1991

- ↑ The New York Times & 29 June 1991

- ↑ Narodne novine & 8 October 1991

- ↑ Department of State & 31 January 1994

- ↑ ECOSOC & 17 November 1993, Section J, points 147 & 150

- ↑ EECIS 1999, pp. 272–278

- ↑ The Independent & 10 October 1992

- ↑ The New York Times & 24 September 1991

- ↑ Bjelajac & Žunec 2009, pp. 249–250

- ↑ The New York Times & 18 November 1991

- 1 2 The New York Times & 3 January 1992

- ↑ Los Angeles Times & 29 January 1992

- ↑ Thompson 2012, p. 417

- ↑ The New York Times & 15 July 1992

- ↑ The New York Times & 24 January 1993

- ↑ ECOSOC & 17 November 1993, Section K, point 161

- ↑ The New York Times & 13 September 1993

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 382

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 427

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 428

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 10

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 433

- ↑ Ramet 2006, p. 443

- ↑ The Seattle Times & 16 July 1992

- ↑ The New York Times & 17 August 1995

- ↑ Woodward 2010, p. 432

- 1 2 Jutarnji list & 9 December 2007

- 1 2 Ramet 2006, p. 439

- 1 2 CIA 2002, p. 251

- ↑ CIA 2002, p. 223

- ↑ CIA 2002, pp. 235–242

- ↑ CIA 2002, pp. 230–231

- ↑ Ramić 2004, pp. 88–90

- 1 2 3 4 CIA 2002, p. 242

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 CIA 2002, p. 243

- ↑ Ramić 2004, p. 92

- 1 2 3 Ramić 2004, p. 100

- 1 2 Ramić 2004, p. 85

- 1 2 Ramić 2004, p. 87

- 1 2 3 Ramić 2004, p. 132

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 HRHB & 4 November 1994

- ↑ Ramić 2004, p. 141

- ↑ Marić 2017

- 1 2 Ramić 2004, p. 102

- 1 2 Ramić 2004, p. 106

- 1 2 Ramić 2004, p. 120

- 1 2 3 Ramić 2004, p. 122

- 1 2 Ramić 2004, p. 124

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Marić 2017, pp. 103

- ↑ Ramić 2004, pp. 99–100

- ↑ Ramić 2004, pp. 115–116

- 1 2 CIA 2002, pp. 242–243

- ↑ Ramić 2004, p. 135

- 1 2 CIA 2002, note 237/V

- 1 2 Ramić 2004, pp. 137–141

- ↑ Ramić 2004, p. 162

- ↑ Ramić 2004, p. 142

- 1 2 HRHB & 3 November 1994

- ↑ Ripley 1999, p. 86

- 1 2 3 Ramić 2004, pp. 149–150

- ↑ Kupreški Radio & 3 November 2012

- ↑ Caspersen 2010, p. 155

- ↑ CIA 2002, note 227/V

- ↑ Bono 2003, p. 107

- ↑ Hrvatski vojnik & July 2010

References

- Books

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Russian and European Analysis (2002). Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. OCLC 50396958.

- Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. Routledge. 1999. ISBN 978-1-85743-058-5.

- Bjelajac, Mile; Žunec, Ozren (2009). "The War in Croatia, 1991–1995". In Charles W. Ingrao; Thomas Allan Emmert. Confronting the Yugoslav Controversies: A Scholars' Initiative. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-533-7. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Bono, Giovanna (2003). Nato's 'Peace Enforcement' Tasks and 'Policy Communities': 1990–1999. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-0944-5. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Caspersen, Nina (2010). Contested Nationalism: Serb Elite Rivalry in Croatia and Bosnia in the 1990s. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-726-6. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building And Legitimation, 1918–2006. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Ramić, Edin (2004). Kupreška operacija, jesen 1994. godine [Kupres Operation, Autumn of 1994] (in Bosnian). Bošnjačka zajednica kulture Preporod. ISBN 978-9958-9435-0-8. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- Marić, Dušan (2017). Sinovi Vitoroga [Sons of Vitorog] (in Serbian). Dušan Marić, Velika Plana. ISBN 978-86-910309-4-0.

- Ripley, Tim (1999). Operation deliberate force: the UN and NATO campaign in Bosnia 1995. Centre for Defence and International Security Studies. ISBN 978-0-9536650-0-6. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- Thompson, Wayne C. (2012). Nordic, Central & Southeastern Europe 2012. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-61048-891-4. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Woodward, Susan L. (2010). "The Security Council and the Wars in the Former Yugoslavia". In Vaughan Lowe; Adam Roberts; Jennifer Welsh; Dominik Zaum. The United Nations Security Council and War:The Evolution of Thought and Practice since 1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-161493-4. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- News reports

- "Roads Sealed as Yugoslav Unrest Mounts". The New York Times. Reuters. 19 August 1990. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- Engelberg, Stephen (3 March 1991). "Belgrade Sends Troops to Croatia Town". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- Sudetic, Chuck (2 April 1991). "Rebel Serbs Complicate Rift on Yugoslav Unity". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- Sudetic, Chuck (26 June 1991). "2 Yugoslav States Vote Independence To Press Demands". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Sudetic, Chuck (29 June 1991). "Conflict in Yugoslavia; 2 Yugoslav States Agree to Suspend Secession Process". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Cowell, Alan (24 September 1991). "Serbs and Croats: Seeing War in Different Prisms". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Sudetic, Chuck (18 November 1991). "Croats Concede Danube Town's Loss". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Sudetic, Chuck (3 January 1992). "Yugoslav Factions Agree to U.N. Plan to Halt Civil War". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- Williams, Carol J. (29 January 1992). "Roadblock Stalls U.N.'s Yugoslavia Deployment". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- Kaufman, Michael T. (15 July 1992). "The Walls and the Will of Dubrovnik". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Maass, Peter (16 July 1992). "Serb Artillery Hits Refugees – At Least 8 Die As Shells Hit Packed Stadium". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- Bellamy, Christopher (10 October 1992). "Croatia built 'web of contacts' to evade weapons embargo". The Independent. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Sudetic, Chuck (24 January 1993). "Croats Battle Serbs for a Key Bridge Near the Adriatic". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- "Rebel Serbs List 50 Croatia Sites They May Raid". The New York Times. 13 September 1993. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- Bonner, Raymond (17 August 1995). "Dubrovnik Finds Hint of Deja Vu in Serbian Artillery". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- Vurušić, Vlado (9 December 2007). "Krešimir Ćosić: Amerikanci nam nisu dali da branimo Bihać" [Krešimir Ćosić: Americans did not let us defend Bihać]. Jutarnji list (in Croatian). Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Gašpar, Ivan (3 November 2012). "Kuprešaci proslavili osamnaest godina slobode" [Kupres population celebrates eighteen years of freedom] (in Croatian). Kupreški Radio. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- Other sources

- "Odluka" [Decision]. Narodne novine (in Croatian) (53). 8 October 1991. ISSN 1333-9273. Archived from the original on 23 September 2009. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- "Situation of human rights in the territory of the former Yugoslavia". United Nations Economic and Social Council. 17 November 1993. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Croatian Defence Council, General Staff (3 November 1994). "Izvješće o borbenim djelovanjima" [Report on combat activities] (PDF) (in Croatian). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2013.

- Redman, Mike. "Joint ABiH‐HVO operations 1994: A preliminary analysis of the Battle of Kupres". doi:10.1080/13518040308430578#.UdbYNG35mPU (inactive 2018-09-21).

- "Croatia human rights practices, 1993; Section 2, part d". United States Department of State. 31 January 1994. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Tomanić, Radivoje (2007). "Redovni borbeni izvještaj - Str. pov. br. 2/1-348" [Regular battle report - Top secret nr. 2/1-348]. In Marijan, Davor. Oluja [Storm] (PDF) (in Serbian). Croatian memorial-documentation center of the Homeland War of the Government of Croatia. pp. 273–274. ISBN 978-953-7439-08-8. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- "The Prosecutor vs. Milan Martic - Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 12 June 2007. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- "Oluja - bitka svih bitaka" [Storm - battle of all battles] (in Croatian). Ministry of Defence (Croatia). July 2010. Retrieved 6 February 2013.