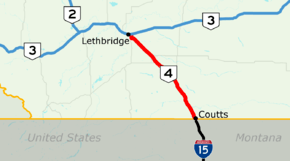

Alberta Highway 4

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Special Service Force Memorial Highway | ||||

Highway 4 highlighted in red | ||||

| Route information | ||||

| Length | 103.4 km[1] (64.2 mi) | |||

| History |

1912 (Sunshine Trail) 1947 (paved) 2009 (Divided expressway complete) | |||

| Major junctions | ||||

| South end |

| |||

| North end |

| |||

| Location | ||||

| Specialized and rural municipalities | Warner No. 5 County, Lethbridge County | |||

| Major cities | Lethbridge | |||

| Towns | Milk River | |||

| Villages | Coutts, Warner | |||

| Highway system | ||||

|

Provincial highways in Alberta

| ||||

| Location | Volume | ± |

|---|---|---|

| Coutts | 2,000 | |

| Milk River | 2,160 | |

| Warner | 2,430 | |

| Stirling | 2,580 | |

| Lethbridge | ||

| 20 Ave S | 14,830 | |

| S Parkside Dr | 19,100 | |

| Hwy 3 | 15,220 | |

Alberta Provincial Highway No. 4, commonly referred to as Highway 4, is a 103-kilometre (64 mi) highway in southern Alberta, Canada that connects Highway 3 in Lethbridge to Interstate 15 in Montana. It begins in Coutts at Alberta's busiest border crossing, winding north through gentle rolling hills and farmlands in the south of the province. It bypasses Milk River, Warner and Stirling before reaching Lethbridge where it becomes 43 Street and ends at Crowsnest Trail on the east side of the city. In 1995, it was designated as part of the CANAMEX Corridor that links Canada to Mexico and the United States, including the major cities of Salt Lake City, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, and San Diego which lie on Interstate 15. In 1999, the highway was renamed the First Special Service Force Memorial Highway in honour of elite soldiers who travelled to Helena, Montana for training before World War II. Between Lethbridge and Highway 61 near Stirling, Highway 4 is signed as part of the Red Coat Trail, a historic route stretching from southern Alberta into Manitoba that is advertised as that which approximates the path travelled by the North-West Mounted Police on their quest to the prairies.

The highway began as a trail parallel to a historic branch of the Canadian Pacific Railway that was built in the late 1800s connecting Lethbridge to Great Falls. It had been named the Sunshine Trail by 1912, and developed into an all-weather gravelled road by the 1930s. Paving and a realignment to eliminate curves was completed by 1947, and in the late 1980s Alberta Transportation announced plans to twin the entire length as part of upgrades to the entire CANAMEX Corridor south of Calgary that included Highways 2 and 3. An expressway bypass of Milk River completed all work in 2009. A bypass of Lethbridge at the highway's northern terminus is also proposed; it would link Highway 4 to a newly aligned Highway 3 north of the city, making Alberta's portion of the CANAMEX Corridor free-flowing from Coutts to Fort Macleod.

Route description

A core route of the National Highway System, Highway 4 is identified as a key international corridor.[3] It is a four-lane divided highway, constructed parallel to a line of the Canadian Pacific Railway.[4] Outside of Lethbridge and Coutts, the highway has a posted speed limit of 110 km/h (68 mph), like most other major divided highways in Alberta outside of urban areas.[5]

Interstate 15 becomes Highway 4 as it crosses the international border between Montana and Alberta into Coutts, the only border crossing between Montana and Alberta that is open 24 hours year-round.[4] The highway curves north out of Coutts alongside the railway to a three-way intersection with Highway 501 which leads west to Del Bonita. The two highways continue concurrently to the north, briefly paralleling Milk River. The concurrency ends and Highway 501 splits to the east into the community of Milk River, becoming Railway Street, while Highway 4 continues north across the river to bypass the town.[6][7]

Highway 4 continues 16 km (9.9 mi) north to Warner, which it bypasses to the east;[8][9] the original alignment of the highway was directly through the community.[10] From Warner, Highway 36 splits to the north en route to Taber and Vauxhall. Highway 4 continues north-northwest to the Hamlet of New Dayton and an intersection with Highway 52 at Craddock, leading west to Raymond. Further north, Stirling Lake and the town of Stirling lie immediately west of Highway 4. New pavement was built east of Stirling to allow the divided highway to curve smoothly to the northeast, and a portion of the former two lane road remains.[11] Just north of Stirling, Highway 61 splits to the east leading to Foremost. North of Stirling, the community of Wilson Siding lies at the intersection of Highway 4 and Highway 845. Highway 4 reaches Lethbridge and curves due west across the CPR tracks becoming 24 Avenue South.[12]

In Lethbridge, the highway turns north onto 43 Street as a major arterial road with a speed limit of 70 km/h (43 mph). It intersects the major east-west arterial routes of 20 Avenue and South Parkside Drive in south Lethbridge before crossing the Canadian Pacific Railway tracks a final time, then ends at an intersection with Crowsnest Trail.[13] With only four traffic lights, it provides an alternative to the busy Mayor Magrath Drive, the main north-south route in Lethbridge, which has a dozen sets of lights over the same distance.[13] The section of 43 Street near 6 Avenue South is the busiest part of Highway 4, carrying over 19,000 vehicles per day in 2017. Between Lethbridge and Wilson Siding, traffic quickly decreases to less than 10,000 vehicles per day, and less than 5,000 vehicles per day for the remaining 86 km (53 mi) until Coutts.[2]

History

Sunshine Trail

.jpg)

Like many other main highways in southern Alberta, the alignment of Highway 4 is based on an existing railway.[14] In the late 1890s, a railway was constructed between Lethbridge and Coutts by the Alberta Railway and Coal Company, who then extended the route to Great Falls, Montana.[15] A spur to the southwest from Stirling to Cardston was also built. A trail developed paralleling the railroad, eventually evolving by 1912 into a dirt road known as part of the Sunshine Trail.[16][17] The route was identified as a key corridor connecting Alberta to major cities of the United States for the purposes of trade and tourist travel.[18] Lethbridge mayor W. D. L. Hardie supported proposals for the road to be gravelled, claiming it would be a relatively easy and affordable process and could set precedent for other gravelling projects in the province.[19] In tandem with the Red Trail (now Highway 3) and Highway 1 (now Highway 2), Highway 4 comprised the north portion of the all-weather Sunshine Trail that would eventually run from Los Angeles to Peace River.[20][21]

The alignment of the highway has changed slightly from its inception to the present day. From its northern end in Lethbridge, it originally followed the railway line on a southeasterly heading before turning due east along Township Road 54 at New Dayton.[10] It then followed present-day Highway 36 south through Warner, before turning back east toward the railway north of Milk River, before following it through the town and into Coutts.[10] In 1938, Lethbridge City council lobbied to the provincial government for the entire route to paved.[22] Along with other Lethbridge officials, they hoped the highway would be given priority over other projects in the area as the Coutts border crossing was far and away the busiest in Alberta, carrying more traffic than all the others combined.[23] Work began in 1945 to reconstruct and straighten out the existing alignment of the highway that consisted of the numerous aforementioned 90° turns.[24] The first section to be reconstructed and paved was from Coutts to Craddock.[25] Work continued on the northern half of the highway and was mostly completed by 1947, with the official opening of the new Lethbridge–Coutts highway held in May 1948 in Coutts.[26] The road was designated as Highway 4 by the following decade.[16][27]

Later years

Prior to the construction of 43 Street, the former alignment of Highway 4 in Lethbridge was along Mayor Magrath Drive, cosigned with Highway 5 to 3 Avenue in south Lethbridge, which was then Highway 3.[28] It was later signed as 24 Avenue past Highway 5 (Mayor Magrath Drive), becoming Scenic Drive and continuing in a northwest direction to Highway 3 near downtown.[29] In 1992, 43 Street in south Lethbridge was widened from two to four lanes, although it did not carry the Highway 4 designation at this time.[30] Ordinarily, Alberta begins to consider upgrading to a divided highway when traffic levels reach 10,000 vehicles per day.[31] The majority of Highway 4 remains well below this threshold, but it is a component of the CANAMEX Corridor in southern Alberta, to which Alberta had made a commitment to upgrading in the late 1980s. Plans for a divided highway were confirmed by 1989, and reiterated as a priority by annual reports published by Alberta Transportation through the 1990s. The highway was the southernmost component of what was then called the Export Highway, which also included Highways 2 and 3, which were given priority for twinning in the first half of the 1990s.[32][33] In 1993, federal and provincial funding was announced for various twinning projects in Alberta, including the entirety of Highway 4.[34]

By 1996, work had begun on a 13 km (8.1 mi) section north of Coutts, and a $26 million commitment had been made by Alberta to a group of projects that included the widening of Highway 4 in Lethbridge.[35][36] By 1998, a 12 km (7.5 mi) section south of Lethbridge to Highway 845 had been completed.[37] For the majority of the highway, the newly constructed lanes carried northbound traffic and the existing road was converted to carry southbound traffic.[38] Almost all work had been completed before the end of the decade.[39] On September 18, 1999, Highway 4 was renamed the First Special Service Force Memorial Highway.[40][41] The route was travelled between 1942 and 1944 by Canadian volunteers of the force to join their American counterparts for training at Fort William Henry Harrison near Helena in preparation for World War II.[42][43] Several Canadian and American members of the force that came to be known as the "Devil's Brigade" were on hand in Milk River for the dedication of plaques for the route, and signs at both ends of the highway were erected.[43] Interstate 15 between Sweet Grass and Helena had received the same name in 1996.[40]

The section of Highway 4 through Milk River was the last remaining section that was not a divided expressway. Work had been delayed by land acquisition and some uncertainty on the final routing.[39] A bypass east of the town and upgrades to the existing route through the community had been considered, but ultimately a new twinned highway west of the town, and a relocation of the railway, was chosen.[39] The $59 million project included the construction of two bridges over Milk River and was completed in 2009.[44]

Future

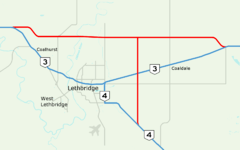

Alberta Transportation has proposed the construction of a freeway bypass of Lethbridge, tentatively called Highway 4X. In combination with proposed bypasses of Fort Macleod, Claresholm and Nanton, the project would eliminate all traffic lights on the CANAMEX Corridor in southern Alberta.[1][45] In a study completed by Stantec, the recommended alignment of the route would split from the existing Highway 4 southeast of Lethbridge between Range Roads 210 and 205, approximately equidistant between Lethbridge and Wilson Siding.[45]:11 The divided highway would proceed due north, crossing Highway 3 between Lethbridge and Coaldale to a second new highway north of the city serving as a realigned Lethbridge bypass of Highway 3 between Township Roads 94 and 100. The alternative to a bypass project would be a significant upgrading of Crowsnest Trail to a freeway standard through Lethbridge. This upgrade would potentially require relocation of the adjacent CPR railway line, and significant demolition of adjacent properties. During the study, the city of Lethbridge indicated that this disruptive alignment would be rejected, hence the need for a bypass outside of city limits to the east and north.[45]:5 In 2005, the entire project was estimated to cost $546 million.[45]:12

Major intersections

| Rural/specialized municipality | Location | km[8] | mi | Destinations | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| County of Warner No. 5 | Coutts | 0.0 | 0.0 | Continues into Montana | |||

| Canada–United States border at Sweetgrass–Coutts Border Crossing | |||||||

| 1.3 | 0.81 | ||||||

| | 16.1 | 10.0 | South end of Hwy 501 concurrency | ||||

| Milk River | 19.2 | 11.9 | North end of Hwy 501 concurrency; former Hwy 4 alignment | ||||

| 19.5 | 12.1 | Crosses Milk River | |||||

| 21.5 | 13.4 | North Milk River access | Former Hwy 4 alignment | ||||

| Warner | 37.8 | 23.5 | |||||

| | 46.2 | 28.7 | |||||

| | 65.8 | 40.9 | |||||

| Stirling | 74.2 | 46.1 | South end of Red Coat Trail designation | ||||

| Lethbridge County | | 86.4 | 53.7 | ||||

| | 88.8 | 55.2 | |||||

| City of Lethbridge | 99.5 | 61.8 | 43 Street | North end of Red Coat Trail designation;[46] Hwy 4 turns north along 43 Street | |||

| 101.0 | 62.8 | South Parkside Drive | |||||

| 102.7 | 63.8 | ||||||

| 103.4 | 64.2 | CANAMEX Corridor follow Hwy 3 west | |||||

| Continues as 43 Street to Hwy 843 | |||||||

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| |||||||

See also

Route map:

Notes

- ↑ Alberta Transportation publishes yearly traffic volume data for provincial highways.[2] The table compares the AADT at several locations along Highway 4 using data from 2017, expressed as an average daily vehicle count over the span of a year (AADT).[2] In the trend column, a red arrow indicates a decrease in volume compared to 2016, and a green arrow indicates an increase.[2]

References

- 1 2 "2016 Provincial Highway 1-216 Progress Chart" (PDF). Alberta Transportation. March 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 12, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Traffic Volume Data on Google Maps". Alberta Transportation. 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ↑ "National Highway System". Transport Canada. December 20, 2011. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- 1 2 Alberta Official Road Map (Map) (2010 ed.). Alberta Tourism, Parks and Recreation. § N–6, N-7, O–7.

- ↑ Davison, Janet (August 29, 2014). "Is it time for higher speed limits on Canada's highways". CBC News. Archived from the original on April 12, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ↑

"CANAMEX Trade Corridor". Alberta Transportation. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

Many projects have contributed to the overall efficiency of the CANAMEX/North-South Trade Corridor... [including] the completion of the Milk River bypass along Highway 4...

- ↑ Google (May 2016). "Highway 4 Bypassing Milk River, Alberta". Google Street View. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- 1 2 Google (November 13, 2016). "Highway 4 in southern Alberta" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- ↑ Google (May 2016). "Highway 4 Bypassing Warner, Alberta". Google Street View. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Map of the province of Alberta, Canada". Peel's Prairie Provinces. Edmonton: Department of Lands and Mines. 1931. Retrieved December 3, 2016 – via University of Alberta.

- ↑ Google (November 4, 2016). "Aerial view: Highway 4 near Stirling" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- ↑ Google (May 2016). "Highway 4 in Lethbridge". Google Street View. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- 1 2 Google (October 28, 2016). "Highway 4 in Lethbridge" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Calgary District, Alberta". Peel's Prairie Provinces. Ottawa: Topographical Survey of Canada, Department of the Interior. February 1926. Retrieved October 26, 2016 – via University of Alberta.

- ↑ "Alberta Railway and Coal Company, St. Mary's River". Public Archives of Canada. 2005 [First published 1883]. Retrieved November 4, 2016 – via Atlas of Alberta Railways, University of Alberta Press.

- 1 2 Cashman, Tony (1990). A History of Motoring in Alberta (3rd ed.). Edmonton: Alberta Motor Association.

- ↑ "Motor roads in Western Canada and United States connections leading to Calgary & Canadian Rockies (21 MB)". Alberta Development Board. 1929. Retrieved November 12, 2016 – via University of Calgary.

- ↑ "Provincial Authorities And Great Falls Convention". The Lethbridge Herald. September 13, 1922. p. 1. Retrieved February 18, 2017 – via NewspaperArchive.com. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Mayor Boosts For 'Sunshine Trail'". The Lethbridge Herald. July 6, 1922. p. 7. Retrieved February 18, 2017 – via NewspaperArchive.com. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Groff, Colin (June 29, 1934). "Lure of the Sunshine Trail". The Lethbridge Herald. p. 5. Retrieved February 18, 2017 – via NewspaperArchive.com. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "International Good Roads Body Plans Promotion of the 'Sunshine Trail'". The Lethbridge Herald. July 6, 1922. p. 1. Retrieved February 18, 2017 – via NewspaperArchive.com. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Surfacing of Roads Is Urged by City Council". The Lethbridge Herald. October 12, 1938. p. 6. Retrieved February 18, 2017 – via NewspaperArchive.com. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Annual Report Lethbridge Board of Trade". The Lethbridge Herald. February 22, 1940. pp. 8, 10. Retrieved February 18, 2017 – via NewspaperArchive.com. (Subscription required (help)).

Strong representations were made to the Minister of Public Works regarding the hard-surfacing of the Lehbridge-Coutts highway as against any other project.

- ↑ "Start Road Work Soon". The Lethbridge Herald. April 3, 1945. p. 1. Retrieved February 18, 2017 – via NewspaperArchive.com. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Surfacing is Proceeding on No. 3 And 4 Highways". The Lethbridge Herald. September 8, 1947. p. 7. Retrieved February 18, 2017 – via NewspaperArchive.com. (Subscription required (help)).

Surfacing was proceeding on highway No. 3 between Lethbridge and Coutts, with traffic being accommodated on the old and new highways.

- ↑ "Urges Citizens to Go to Coutts". The Lethbridge Herald. May 4, 1948. p. 11. Retrieved February 18, 2017 – via NewspaperArchive.com. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Mayor Magrath Drive Upgrade: Balancing Road Efficiency With Business Access" (PDF). Stantec Consulting Ltd. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 13, 2016. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Lethbridge, Alberta: West of Fourth Meridian (131 MB)". Surveys and Mapping Branch, Department of Mines and Technical Surveys. 1966. Retrieved November 12, 2016 – via University of Calgary, University of Alberta.

- ↑ "Lethbridge Historical Walking Tour" (PDF). Sir Alexander Galt Museum & Archives. p. 2. Retrieved November 5, 2016 – via Alberta.ca.

- ↑ "1991/1992 Annual Report". Edmonton: Alberta Transportation and Utilities. 1992. p. 30. Retrieved November 4, 2016 – via University of Alberta Libraries.

- ↑ Barnes, Dan (May 27, 2012). "Treat Fort McMurray like Grand Prairie, former MLA insists". Edmonton Journal. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ↑ "Highway 4 twinning distant". The Lethbridge Herald. August 28, 1992. p. 5. Retrieved February 20, 2017 – via NewspaperArchive.com. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "1988/1989 Annual Report". Edmonton: Alberta Transportation and Utilities. 1989. p. 38. Retrieved November 4, 2016 – via University of Alberta Libraries.

Development was completed on a proposal to twin the Export Highway (Highways 2, 3 and 4) connecting to the U.S. Border.

- ↑ "Highway to border to be twinned". March 19, 1993. p. 1. Retrieved February 20, 2017 – via NewspaperArchive.com. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "1996/1997 Annual Report" (PDF). Edmonton: Alberta Transportation and Utilities. 1997. p. 13. Retrieved November 4, 2016 – via University of Alberta Libraries.

- ↑ "1997/1998 Annual Report" (PDF). Edmonton: Alberta Transportation and Utilities. 1998. p. 15. Retrieved November 4, 2016 – via University of Alberta Libraries.

- ↑ "1998/1999 Annual Report". Edmonton: Alberta Transportation and Utilities. 1999. p. 38. Retrieved November 4, 2016 – via University of Alberta Libraries.

- ↑ "Planning set in motion to expand Highway 4". January 14, 1996. p. 4. Retrieved February 20, 2017 – via NewspaperArchive.com. (Subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 "Highway 4 twinning distant". The Lethbridge Herald. February 11, 2005. p. 6. Retrieved February 20, 2017 – via NewspaperArchive.com. (Subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 "Highway renaming set for this weekend". The Lethbridge Herald. September 15, 1999. p. 4. Retrieved February 20, 2017 – via NewspaperArchive.com. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Fighting men saluted". Winnipeg Free Press. September 19, 1999. p. 15. Retrieved February 20, 2017 – via NewspaperArchive.com. (Subscription required (help)).

Highway 4 [...] has officially been renamed the First Special Service Force Memorial Highway.

- ↑ "New Plaque Commemorates the First Special Service Force". CHLB-FM News. November 4, 2014. Archived from the original on October 24, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- 1 2 "Devil's Brigade". The Lethbridge Herald. September 19, 1999. p. 15. Retrieved February 20, 2017 – via NewspaperArchive.com. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Milk River bypass replaces last two-lane section of Highway 4". Alberta Transportation. October 27, 2007. Archived from the original on March 25, 2015. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Highways 3 & 4 - Lethbridge and Area NHS & NTSC Functional Planning Study: Final Report" (PDF). Stantec Consulting Ltd. Alberta Transportation. February 2006. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ↑ Google (April 2014). "Red Coat Trail sign" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved September 30, 2017.