Achromatopsia

| Achromatopsia | |

|---|---|

| Synonym | Total color blindness |

| |

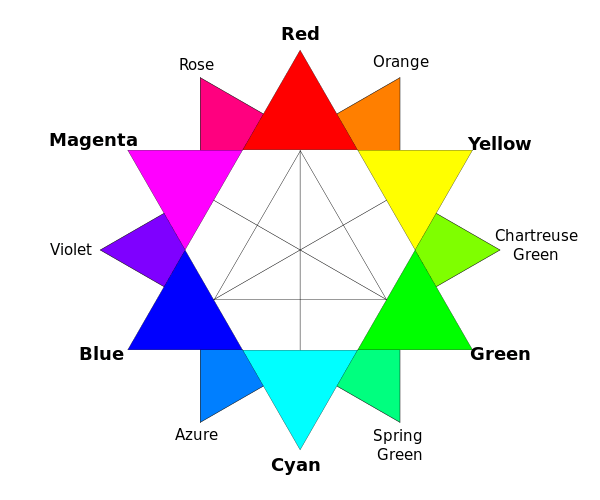

| A person with complete achromatopsia would see only black, white and shades of grey. Additionally, the image would usually be very blurry in brighter light but would be less blurry at very low lighting levels. | |

| Specialty |

Ophthalmology |

| Symptoms | Amblyopia, hemeralopia, nystagmus, photophobia |

| Causes |

|

| Diagnostic method | Electroretinography |

| Frequency | ⩽1:30,000[1] |

Achromatopsia (ACHM), also known as total color blindness, is a medical syndrome that exhibits symptoms relating to at least five conditions. The term may refer to acquired conditions such as cerebral achromatopsia, but it typically refers to an autosomal recessive congenital color vision condition, the inability to perceive color and to achieve satisfactory visual acuity at high light levels (typically exterior daylight). The syndrome is also present in an incomplete form which is more properly defined as dyschromatopsia. It is estimated to affect 1 in 30,000 live births worldwide.

There is some discussion as to whether achromats can see color or not. As illustrated in The Island of the Colorblind by Oliver Sacks, some achromats cannot see color, only black, white, and shades of grey. With five different genes currently known to cause similar symptoms, it may be that some do see marginal levels of color differentiation due to different gene characteristics. With such small sample sizes and low response rates, it is difficult to accurately diagnose the 'typical achromatic conditions'. If the light level during testing is optimized for them, they may achieve corrected visual acuity of 20/100 to 20/150 at lower light levels, regardless of the absence of color.

One common trait is hemeralopia or blindness in full sun. In patients with achromatopsia, the cone system and fibres carrying color information remain intact. This indicates that the mechanism used to construct colors is defective.

Terminology

Total color blindness can be classified as:

Related terms:

Signs and symptoms

The syndrome is frequently noticed first in children around six months of age by their photophobic activity and/or their nystagmus. The nystagmus becomes less noticeable with age but the other symptoms of the syndrome become more relevant as school age approaches. Visual acuity and stability of the eye motions generally improve during the first 6–7 years of life (but remain near 20/200). The congenital forms of the condition are considered stationary and do not worsen with age.

The five symptoms associated with achromatopsia/dyschromatopsia are:

- Achromatopsia

- Amblyopia (reduced visual acuity)

- Hemeralopia (with the subject exhibiting photophobia)

- Nystagmus

- Iris operating abnormalities

The syndrome of achromatopsia/dyschromatopsia is poorly described in current medical and neuro-ophthalmological texts. It became a common term following the popular book by the neuroscientist Oliver Sacks, "The Island of the Colorblind" in 1997. Up to that time most color-blind subjects were described as achromats or achromatopes. Those with a lesser degree of color perception abnormality were described as either protanopes, deuteranopes or tetartanopes (historically tritanopes).

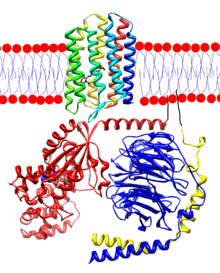

Achromatopsia has also been called rod monochromacy and total congenital color blindness. Individuals with the congenital form of this condition show complete absence of cone cell activity via electroretinography at high light levels. There are at least four genetic causes of congenital ACHM, two of which involve cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels (ACHM2/ACHM3), a third involves the cone photoreceptor transducin (GNAT2, ACHM4), and the last remains unknown.

Complete achromatopsia

Aside from a complete inability to see color, individuals with complete achromatopsia have a number of other ophthalmologic aberrations. Included among these aberrations are greatly decreased visual acuity (<0.1 or 20/200) in daylight, Hemeralopia, nystagmus, and severe photophobia. The fundus of the eye appears completely normal.

Incomplete achromatopsia (dyschromatopsia)

In general, symptoms of incomplete achromatopsia are similar to those of complete achromatopsia except in a diminished form. Individuals with incomplete achromatopsia have reduced visual acuity with or without nystagmus or photophobia. Furthermore, these individuals show only partial impairment of cone cell function but again have retained rod cell function.

Cause

Acquired

Acquired achromatopsia/dyschromatopsia is a condition associated with damage to the diencephalon (primarily the thalamus of the mid brain) or the cerebral cortex (the new brain), specifically the fourth visual association area, V4 which receives information from the parvocellular pathway involved in colour processing.

Thalamic achromatopsia/dyschromatopsia is caused by damage to the thalamus; it is most frequently caused by tumor growth since the thalamus is well protected from external damage.

Cerebral achromatopsia is a form of acquired color blindness that is caused by damage to the cerebral cortex of the brain, rather than abnormalities in the cells of the eye's retina. It is most frequently caused by physical trauma, hemorrhage or tumor tissue growth.

Congenital

The known causes of the congenital forms of achromatopsia are all due to malfunction of the retinal phototransduction pathway. Specifically, this form of ACHM seems to result from the inability of cone cells to properly respond to light input by hyperpolarizing. Known genetic causes of this are mutations in the cone cell cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels CNGA3 (ACHM2) and CNGB3 (ACHM3) as well as the cone cell transducin, GNAT2 (ACHM4).

A fourth genetic cause (ACHM5, OMIM 613093) was discovered in 2009.[3] It is a mutation of gene PDE6C, located on chromosome locus 10, 10q24. It is estimated that less than 2% of achromatopsias are caused by a mutation in this gene.

Pathophysiology

The hemeralopic aspect of ACHM can be diagnosed non-invasively using electroretinography. The response at low (scotopic) and median (mesotopic) light levels will be normal but the response under high light level (photopic) conditions will be absent. The mesotopic level is approximately 100 times lower than the clinical level used for the typical high level electroretinogram. When as described, the condition is due to a saturation in the neural portion of the retina and not due to the absence of the photoreceptors per se.

In general, the molecular pathomechanism of ACHM is either the inability to properly control or respond to altered levels of cGMP. cGMP is particularly important in visual perception as its level controls the opening of cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels (CNGs). Decreasing the concentration of cGMP results in closure of CNGs and resulting hyperpolarization and cessation of glutamate release. Native retinal CNGs are composed of 2 α- and 2 β-subunits, which are CNGA3 and CNGB3, respectively, in cone cells. When expressed alone, CNGB3 cannot produce functional channels, whereas this is not the case for CNGA3. Coassembly of CNGA3 and CNGB3 produces channels with altered membrane expression, ion permeability (Na+ vs. K+ and Ca2+), relative efficacy of cAMP/cGMP activation, decreased outward rectification, current flickering, and sensitivity to block by L-cis-diltiazem. Mutations tend to result in the loss of CNGB3 function or gain of function (often increased affinity for cGMP) of CNGA3. cGMP levels are controlled by the activity of the cone cell transducin, GNAT2. Mutations in GNAT2 tend to result in a truncated and, presumably, non-functional protein, thereby preventing alteration of cGMP levels by photons. There is a positive correlation between the severity of mutations in these proteins and the completeness of the achromatopsia phenotype.

Molecular diagnosis can be established by identification of biallelic variants in the causative genes. Molecular genetic testing approaches used in ACHM can include targeted analysis for the common CNGB3 variant c.1148delC (p.Thr383IlefsTer13), use of a multigenerational panel, or comprehensive genomic testing.

ACHM2

While some mutations in CNGA3 result in truncated and, presumably, non-functional channels this is largely not the case. While few mutations have received in-depth study, see table 1, at least one mutation does result in functional channels. Curiously, this mutation, T369S, produces profound alterations when expressed without CNGB3. One such alteration is decreased affinity for Cyclic guanosine monophosphate. Others include the introduction of a sub-conductance, altered single-channel gating kinetics, and increased calcium permeability. When mutant T369S channels coassemble with CNGB3, however, the only remaining aberration is increased calcium permeability.[4] While it is not immediately clear how this increase in Ca2+ leads to ACHM, one hypothesis is that this increased current decreases the signal-to-noise ratio. Other characterized mutations, such as Y181C and the other S1 region mutations, result in decreased current density due to an inability of the channel to traffic to the surface.[5] Such loss of function will undoubtedly negate the cone cell's ability to respond to visual input and produce achromatopsia. At least one other missense mutation outside of the S1 region, T224R, also leads to loss of function.[4]

ACHM3

While very few mutations in CNGB3 have been characterized, the vast majority of them result in truncated channels that are presumably non-functional, table 2. This will largely result in haploinsufficiency, though in some cases the truncated proteins may be able to coassemble with wild-type channels in a dominant negative fashion. The most prevalent ACHM3 mutation, T383IfsX12, results in a non-functional truncated protein that does not properly traffic to the cell membrane.[6][7] The three missense mutations that have received further study show a number of aberrant properties, with one underlying theme. The R403Q mutation, which lies in the pore region of the channel, results in an increase in outward current rectification, versus the largely linear current-voltage relationship of wild-type channels, concomitant with an increase in cGMP affinity.[7] The other mutations show either increased (S435F) or decreased (F525N) surface expression but also with increased affinity for cAMP and cGMP.[6][7] It is the increased affinity for cGMP and cAMP in these mutants that is likely the disorder-causing change. Such increased affinity will result in channels that are insensitive to the slight concentration changes of cGMP due to light input into the retina.

| Table 2: Summary of CNGB3 mutations found in achromatopsia patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation | Region | Functional? (known or predicted) |

Effect | References | |

| Nucleotide | Amino acid | ||||

| c.29_30insA | p.K10fsX9 | N-Term | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | |

| c.C112T | p.Q38X | N-Term | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | |

| c.C391T | p.Q131X | N-Term | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | |

| c.A442G | p.K148E | N-Term | Kohl et al. (2005) | ||

| c.446_447insT | p.K149NfsX29 | N-Term | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | |

| c.C467T | p.S156F | N-Term | Kohl et al. (2005) | ||

| c.595delG | p.E199SfsX2 | N-Term | No? | Johnson et al. (2004) | |

| c.C607T | p.R203X | N-Term | No? | Kohl et al. (2005); Kohl et al. (2000) | |

| c.G644-1C | Splicing | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | ||

| c.C646T | p.R216X | N-Term | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | |

| c.682_683insG | p.A228GfsX2 | S1 | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | |

| c.G702A | p.W234X | S1 | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | |

| c.706_707delinsTT | p. I236FfsX25 | S1 | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | |

| c.819_826del | p.P273fsX13 | S2-3 | No? | Kohl et al. (2000); Sundin et al. (2000) | |

| c.882_892delinsT | p.R295QfsX9 | S2-3 | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | |

| c.C926T | p.P309L | S3 | Kohl et al. (2005) | ||

| c.T991-3G | Splicing | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | ||

| c.G1006T | p.E336X | S4 | No? | Kohl et al. (2005); Kohl et al. (2000) | |

| c.C1063T | p.R355X | S5 | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | |

| c.G1119A | p.W373X | S5 | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | |

| c.1148delC | p.T383IfsX12 | Pore | No | Does not traffic to the surface | Johnson et al. (2004); Peng et al. (2003); Bright et al. (2005); Kohl et al. (2005); Kohl et al. (2000); Sundin et al. (2000) |

| c.G1208A | p.R403Q | Pore | Yes | Increased outward rectification, increased cGMP affinity | Bright et al. (2005) |

| c.G1255T | p.E419X | Pore | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | |

| c.1298_1299del | p. V433fsX27 | S6 | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | |

| c.C1304T | p.S435F | S6 | Yes | Increased affinity for cAMP and cGMP, decreased surface expression, altered ion permeability, decreased single channel conductance, decreased sensitivity for diltiazem | Peng et al. (2003); Kohl et al. (2005); Kohl et al. (2000); Sundin et al. (2000) |

| c.C1432T | p.R478X | C-term | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | |

| c.G1460A | p.W487X | C-term | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | |

| c.1573_1574delinsTT | p.F525N | C-term | Yes | Increased surface expression in oocytes, decreased outward rectification, increased cGMP and cAMP affinity | Johnson et al. (2004); Bright et al. (2005) |

| c.G1578+1A | Splicing | No? | Kohl et al. (2005); Kohl et al. (2000) | ||

| c.T1635A | p.Y545X | cNMP | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | |

| c.G1781+1C | Splicing | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | ||

| c.G1781+1A | Splicing | No? | Kohl et al. (2005) | ||

| c.2160_2180del | p. 720_726del | C-term | Kohl et al. (2005) | ||

| Abbreviations: SX, transmembrane segment number X; SX-Y, linker region between transmembrane segments X and Y; cNMP, cyclic nucleotide (cAMP or cGMP) binding region. | |||||

ACHM4

Upon activation by light, rhodopsin causes the exchange of GDP for GTP in the guanine nucleotide binding protein (G-protein) α-transducing activity polypeptide 2 (GNAT2). This causes the release of the activated α-subunit from the inhibitory β/γ-subunits. This α-subunit then activates a phosphodiesterase that catalyzes the conversion of cGMP to GMP, thereby reducing current through CNG3 channels. As this process is absolutely vital for proper color processing it is not surprising that mutations in GNAT2 lead to achromatopsia. The known mutations in this gene, table 3, all result in truncated proteins. Presumably, then, these proteins are non-functional and, consequently, rhodopsin that has been activated by light does not lead to altered cGMP levels or photoreceptor membrane hyperpolarization.

| Table 3: Summary of GNAT2 mutations found in achromatopsia patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation | Functional? (predicted) |

References | |

| Nucleotide | Amino acid | ||

| c.C235T | p.Q79X | No? | Kohl et al. (2002) |

| c.285_291del | p.Y95fsX61 | No? | Kohl et al. (2002) |

| IVS3+365_IVS4+974del | p.A101fsX12 | No? | Kohl et al. (2002) |

| c.503_504insT | p. L168fsX3 | No? | Kohl et al. (2002) |

| c.802_803insTCAA | p. L268fsX9 | No? | Kohl et al. (2002) |

| c.955del | p. I319SfsX5 | No? | Kohl et al. (2002) |

Management

There is generally no treatment to cure achromatopsia. However, dark red or plum colored filters are very helpful in controlling light sensitivity.[8]

Since 2003, there is a cybernetic device called eyeborg that allows people to perceive color through sound waves.[9] Achromatopsic artist Neil Harbisson was the first to use such a device in early 2004, the eyeborg allowed him to start painting in color by memorizing the sound of each color.[10]

Moreover, there is some research on gene therapy for animals with achromatopsia, with positive results on mice and young dogs, but less effectiveness on older dogs. However, no experiments have been made on humans. There are many challenges to conducting gene therapy for color blindness on humans.

Epidemiology

Achromatopsia is a relatively uncommon disorder, with a prevalence of 1 in 30,000 people.[1] However, in the small Micronesian atoll of Pingelap approximately 5% of the atoll's 3000 inhabitants are afflicted.[11][12] This is the result of a population bottleneck caused by a typhoon and ensuing famine in the 1770s, which killed all but about twenty islanders, including one who was heterozygous for achromatopsia. The people of this region have termed achromatopsia "maskun", which literally means "not see" in Pingelapese[13]. This unusual population drew neurologist Oliver Sacks to the island for which he wrote his 1997 book, The Island of the Colorblind.[14]

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 François (1961).

- ↑ Duke-Elder & Wybar (1976).

- ↑ Thiadens et al. (2009), pp. 240–47.

- 1 2 Tränkner et al. (2004), pp. 138–47.

- ↑ Patel et al. (2005), pp. 2282–90.

- 1 2 Peng et al. (2003), pp. 34533–40.

- 1 2 3 Bright et al. (2005), pp. 1141–50.

- ↑ Corn & Erin (2010), p. 233.

- ↑ Ronchi (2009).

- ↑ Pearlman (2015), pp. 84–90.

- ↑ Brody et al. (1970), pp. 1253–57.

- ↑ Hussels & Morton (1972), pp. 304–09.

- ↑ Morton et al. (1972), pp. 277–89.

- ↑ Sacks (1997).

Bibliography

- Duke-Elder, S.; Wybar, K.C. (1976) [1973]. Ocular Motility and Strabismus. System of Ophthalmology. 6. London: Kimpton. ISBN 9780853137764. OCLC 37444083.

- Corn, A.N.; Erin, J.N. (2010). Foundations of Low Vision: Clinical and Functional Perspectives. Arlington: AFB Press. ISBN 9780891288831. OCLC 943239210.

- François, J. (1961). Heredity in Ophthalmology. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 9780853132219. OCLC 612180204.

- Ronchi, A.M. (2009). eCulture: Cultural Content in the Digital Age. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 9783540752738. OCLC 799555170.

- Sacks, O. (1997). The Island of the Colorblind. Sydney: Picador. ISBN 9780330358873. OCLC 37444083.

Journals

- Bright, S.R.; Brown, T.E.; Varnum, M.D. (2005). "Disease-associated mutations in CNGB3 produce gain of function alterations in cone cyclic nucleotide-gated channels". Mol. Vis. 11: 1141–1150. PMID 16379026.

- Brody, J.A.; Hussels, I.E.; Brink, E.; et al. (1970). "Hereditary blindness among Pingelapese people of Eastern Caroline Islands". Lancet. 1 (7659): 1253–1257. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(70)91740-X. PMID 4192495.

- Hussels, I.E.; Morton, N.E. (1972). "Pingelap and Mokil Atolls: achromatopsia". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 24 (3): 304–309. PMC 1762260. PMID 4555088.

- Johnson, S.; Michaelides, M.; Aligianis, I.A.; et al. (2004). "Achromatopsia caused by novel mutations in both CNGA3 and CNGB3". J. Med. Genet. 41 (2): e20. doi:10.1136/jmg.2003.011437. PMC 1735666. PMID 14757870.

- Kohl, S.; Marx, T.; Giddings, I. (1998). "Total colourblindness is caused by mutations in the gene encoding the alpha-subunit of the cone photoreceptor cGMP-gated cation channel". Nat. Genet. 19 (3): 257–259. doi:10.1038/935. PMID 9662398.

- Kohl, S.; Baumann, B.; Broghammer, M. (2000). "Mutations in the CNGB3 gene encoding the beta-subunit of the cone photoreceptor cGMP-gated channel are responsible for achromatopsia (ACHM3) linked to chromosome 8q21". Hum. Mol. Genet. 9 (14): 2107–2116. doi:10.1093/hmg/9.14.2107. PMID 10958649.

- Kohl, S.; Baumann, B.; Rosenberg, T. (2002). "Mutations in the cone photoreceptor G-protein alpha-subunit gene GNAT2 in patients with achromatopsia". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71 (2): 422–425. doi:10.1086/341835. PMC 379175. PMID 12077706.

- Kohl, S.; Varsanyi, B.; Antunes, G.A. (2005). "CNGB3 mutations account for 50% of all cases with autosomal recessive achromatopsia". Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 13 (3): 302–308. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201269. PMID 15657609.

- Morton, N.E.; Hussels, I.E.; Lew, R.; et al. (1972). "Pingelap and Mokil Atolls: historical genetics". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 24 (3): 277–289. PMC 1762283. PMID 4537352.

- Patel, K.A.; Bartoli, K.M.; Fandino, R.A. (2005). "Transmembrane S1 mutations in CNGA3 from achromatopsia 2 patients cause loss of function and impaired cellular trafficking of the cone CNG channel". Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46 (7): 2282–2290. doi:10.1167/iovs.05-0179. PMID 15980212.

- Pearlman, E. (2015). "I, Cyborg". PAJ. 37 (2): 84–90. doi:10.1162/PAJJ_a_00264.

- Peng, C.; Rich, E.D.; Varnum, M.D. (2003). "Achromatopsia-associated mutation in the human cone photoreceptor cyclic nucleotide-gated channel CNGB3 subunit alters the ligand sensitivity and pore properties of heteromeric channels". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (36): 34533–34540. doi:10.1074/jbc.M305102200. PMID 12815043.

- Rojas, C.V.; María, L.S.; Santos, J.L.; et al. (2002). "A frameshift insertion in the cone cyclic nucleotide gated cation channel causes complete achromatopsia in a consanguineous family from a rural isolate". Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 10 (10): 638–642. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200856. PMID 12357335.

- Sundin, O.H.; Yang, J.M.; Li, Y. (2000). "Genetic basis of total colourblindness among the Pingelapese islanders". Nat. Genet. 25 (3): 289–293. doi:10.1038/77162. PMID 10888875.

- Thiadens, A.A.H.J.; den Hollander, A.I.; Roosing, S.; et al. (2009). "Homozygosity Mapping Reveals PDE6C Mutations in Patients with Early-Onset Cone Photoreceptor Disorder". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 85 (2): 240–247. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.06.016. PMC 2725240. PMID 19615668.

- Tränkner, D.; Jägle, H.; Kohl, S.; et al. (2004). "Molecular basis of an inherited form of incomplete achromatopsia". J. Neurosci. 24 (1): 138–147. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3883-03.2004. PMID 14715947.

- Wissinger, B.; Gamer, D.; Jägle, H. (2001). "CNGA3 mutations in hereditary cone photoreceptor disorders". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69 (4): 722–737. doi:10.1086/323613. PMC 1226059. PMID 11536077.

External links

- Achromatopsia at American Foundation for the Blind

- Achromatopsia at The BMJ

- Achromatopsia at Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science

- Achromatopsia at MedicineNet

- Achromatopsia at Merriam–Webster Medical

- Achromatopsia at National Center for Biotechnology Information

- Achromatopsia at Royal National Institute of Blind People

- Achromatopsia at ScienceDirect

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |