Constitutional Convention (United States)

The Constitutional Convention[1] (also known as the Philadelphia Convention[1] the Federal Convention,[1] or the Grand Convention at Philadelphia)[2][3] took place from May 25 to September 17, 1787, in the old Pennsylvania State House (now known as Independence Hall) in Philadelphia. Although the Convention was intended to revise the league of states and first system of government under the Articles of Confederation, the intention from the outset of many of its proponents, chief among them James Madison of Virginia and Alexander Hamilton of New York, was to create a new government rather than fix the existing one. The delegates elected George Washington of Virginia, former commanding general of the Continental Army in the late American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) and proponent of a stronger national government, to become President of the Convention. The result of the Convention was the creation of the Constitution of the United States, placing the Convention among the most significant events in American history.

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States of America |

|---|

|

|

Preamble and Articles of the Constitution |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

|

| Unratified Amendments |

|

| History |

| Full text of the Constitution and Amendments |

|

At the time, the convention was not referred to as a "Constitutional" convention, nor did most of the delegates arrive intending to draft a new constitution. Many assumed that the purpose of the convention was to discuss and draft improvements to the existing Articles of Confederation, and would have not agreed to participate otherwise. Once the Convention began, however, most of the delegates – though not all – came to agree in general terms that the goal would be a new system of government, not simply a revised version of the Articles of Confederation.

Several broad outlines were proposed and debated, most notably James Madison's Virginia Plan and William Paterson's New Jersey Plan. The Virginia Plan was selected as the basis for the new government. While the concept of a federal government with three branches (legislative, executive, and judicial) and the general role of each branch was not heavily disputed, several issues delayed further progress and put the success of the Convention in doubt. The most contentious disputes revolved around the composition and election of the Senate as the upper legislative house of a bicameral Congress; whether "proportional representation" was to be defined by a state's geography or by its population, and whether slaves were to be counted; whether to divide the executive power among three people or vest the power in a single chief executive to be called the President; how a president would be elected, for what term, and whether to limit each president to a single term in office; what offenses should be impeachable; the nature of a fugitive slave clause, and whether to allow the abolition of the slave trade; and whether judges should be chosen by the legislature or the executive. Most of the time during the Convention was spent on deciding these issues.

Progress was slow until mid-July when the Connecticut Compromise resolved enough lingering arguments for a draft written by the Committee of Detail to gain acceptance. Though more modifications and compromises were made over the following weeks, most of the rough draft remained in place and can be found in the finished version of the Constitution. After several more issues were resolved, the Committee on Style produced the final version in early September. It was voted on by the delegates, inscribed on parchment with engraving for printing, and signed by thirty-nine of fifty-five delegates on September 17, 1787. The completed proposed Constitution was then released to the public to begin the debate and ratification process.

Historical context

During the American Revolution, the thirteen American states replaced their colonial governments with republican constitutions based on the principle of separation of powers, organizing government into legislative, executive and judicial branches. At the same time, these revolutionary constitutions endorsed legislative supremacy by placing most power in the legislature—since it was viewed as most representative of the people—including power traditionally considered as belonging to the executive and judicial branches. State governors lacked significant authority, and state courts and judges were under the control of the legislative branch.[4]

After declaring independence from Britain in 1776, the thirteen states created a permanent alliance to coordinate American efforts to win the Revolutionary War. This alliance, the United States, was to be governed according to the Articles of Confederation, which was more of a treaty between independent countries than a national constitution.[5] The Articles were adopted by the Second Continental Congress in 1777 but not finally ratified by all states until 1781.[6] During the Confederation Period, the United States was essentially a federation of independent republics, with the Articles guaranteeing state sovereignty and independence. The Confederation was governed by the Congress of the Confederation, a unicameral legislature whose members were chosen by the state legislatures and in which each state cast a single vote.[7] Congress was given a limited set of powers, mainly in the area of waging war and foreign affairs. It could not levy taxes or tariffs, and it could only request money from the states, with no power to force delinquent states to pay.[8] Since the Articles could only be amended by unanimous vote of the states, any state had effective veto power over any proposed change.[9] A super majority (nine of thirteen state delegations) was required for Congress to pass major legislation such as declaring war, making treaties, or borrowing money.[10] The Confederation had no executive or judicial branches, which meant the Confederation government lacked effective means to enforce its own laws and treaties against state non-compliance.[11] It soon became evident to nearly all that the Confederation government, as originally organized, was inadequate for managing the various problems confronting the United States.[9]

Once the immediate task of winning the war had passed, states began to look to their own interests rather than those of the whole country. By the mid-1780s, states were refusing to provide Congress with funding, which meant the Confederation government could not pay the interest on its foreign debt, pay soldiers stationed along the Ohio River or defend American navigation rights on the Mississippi River against Spanish interference.[12] In 1782, Rhode Island vetoed an amendment that would have allowed Congress to levy taxes on imports in order to pay off federal debts. A second attempt was made to approve a federal impost in 1785; however, this time it was New York which disapproved.[13]

The Confederation Congress also lacked the power to regulate foreign and interstate commerce. Britain, France and Spain imposed various restrictions on American ships and products, while the US was unable to coordinate retaliatory trade policies. When states like Massachusetts or Pennsylvania placed reciprocal duties on British trade, neighboring states such as Connecticut and Delaware established free ports to gain an economic advantage. In the 1780s, some states even began applying customs duties against the trade of neighboring states.[14] In 1784, Congress proposed an amendment to give it powers over foreign trade; however, it failed to receive unanimous approval by the states.[15]

Many upper class Americans complained that state constitutions were too democratic and, as a result, legislators were more concerned with maintaining popular approval than doing what was best for the nation. The most pressing example was the way state legislatures responded to calls for economic relief in the 1780s. Many people were unable to pay taxes and debts due to a post-war economic depression that was exacerbated by a scarcity of gold and silver specie. States responded by issuing paper currency, which had a tendency to depreciate in value, and by making it easier to defer tax and debt payments. These policies favored debtors at the expense of creditors, and it was proposed that Congress be given power to prevent such populist laws.[16]

When the government of Massachusetts refused to enact similar relief legislation, rural farmers resorted to violence in Shays' Rebellion (1786–1787). This rebellion was led by a former Revolutionary War captain, Daniel Shays, a small farmer with tax debts, who had never received payment for his service in the Continental Army. The rebellion took months for Massachusetts to put down completely, and some desired a federal army that would be able to put down such insurrections.[17]

These and other issues greatly worried many of the Founders that the Union as it existed up to that point was in danger of breaking apart.[18][19] In September 1786, delegates from five states met at the Annapolis Convention and invited all states to a larger convention to be held in Philadelphia in 1787. The Confederation Congress later endorsed this convention "for the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation".[20] Rhode Island was the only state that refused to send delegates, though it would become the last state to ratify the Constitution in May 1790.[21]

Operations and procedures

Originally planned to begin on May 14, the Convention had to be postponed when very few of the selected delegates were present on that day due to the difficulty of travel in the late 18th century. On May 14, only delegates from Virginia and Pennsylvania were present.[22] It was not until May 25 that a quorum of seven states was secured and the Convention could begin inside the Pennsylvania State House.[22] New Hampshire delegates would not join the Convention until July 23, more than halfway through the proceedings.[23]

The first thing the Convention did was choose a presiding officer, unanimously electing George Washington president of the Convention.[24] The Convention then adopted rules to govern its proceedings. The rules gave each state delegation a single vote either for or against a proposal in accordance with the majority opinion of the state's delegates.[25] This rule increased the power of the smaller states.[26]

When a state's delegates divided evenly on a motion, the state did not cast a vote. Throughout the Convention, delegates would regularly come and go, with only 30–40 being present on a typical day, and each state had its own quorum requirements. Maryland and Connecticut allowed a single delegate to cast its vote. New York required all three of its delegates to be present. If too few of a state's delegates were in attendance, the state did not cast a vote. After two of New York's three delegates abandoned the Convention in mid July with no intention of returning, New York was left unable to vote on any further proposals at the Convention, although Alexander Hamilton would continue to periodically attend and occasionally to speak during the debates.[25][26]

The rules allowed delegates to demand reconsideration of any decision previously voted on. This allowed the delegates to take straw votes in order to measure the strength of controversial proposals and to change their minds as they worked for consensus.[27] It was also agreed that the discussions and votes would be kept secret until the conclusion of the meeting.[28] Despite the sweltering summer heat, the windows of the meeting hall were nailed shut to keep the proceedings a secret from the public.[29] Although William Jackson was elected as secretary, his records were brief and included very little detail. Madison's Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787, supplemented by the notes of Robert Yates, remain the most complete record of the Convention.[30] Due to the pledge to secrecy, Madison's account was not published until after his death in 1836.[31]

Madison's blueprint

James Madison of Virginia arrived in Philadelphia eleven days early and determined to set the Convention's agenda.[32] Prior to the Convention, Madison studied republics and confederacies throughout history, such as ancient Greece and contemporary Switzerland.[33] In April 1787, he drafted a document entitled "Vices of the Political System of the United States", which systematically evaluated the American political system and offered solutions for its weaknesses.[34] Due to his advance preparation, Madison's blueprint for constitutional revision became the starting point for the Convention's deliberations.[35]

Madison believed the solution to America's problems was to be found in a strong central government.[33] Congress needed compulsory taxation authority as well as power to regulate foreign and interstate commerce.[32] To prevent state interference with the federal government's authority, Madison believed there needed to be a way to enforce the federal supremacy, such as an explicit right of Congress to use force against non-compliant states and the creation of a federal court system. Madison also believed the method of representation in Congress had to change. Since under Madison's plan, Congress would exercise authority over citizens directly—not simply through the states—representation ought to be apportioned by population, with larger states having more votes in Congress.[36]

Madison was also concerned with preventing a tyranny of the majority. The government needed to be neutral between the various factions or interest groups that divided society—creditors and debtors, rich and poor, or farmers, merchants and manufacturers. Madison believed that a single faction could more easily control the government within a state but would have a more difficult time dominating a national government comprising many different interest groups. The government could be designed in such a way to further insulate officeholders from the pressures of a majority faction. To protect both national authority and minority rights, Madison believed Congress should be granted veto power over state laws.[37]

Early debates

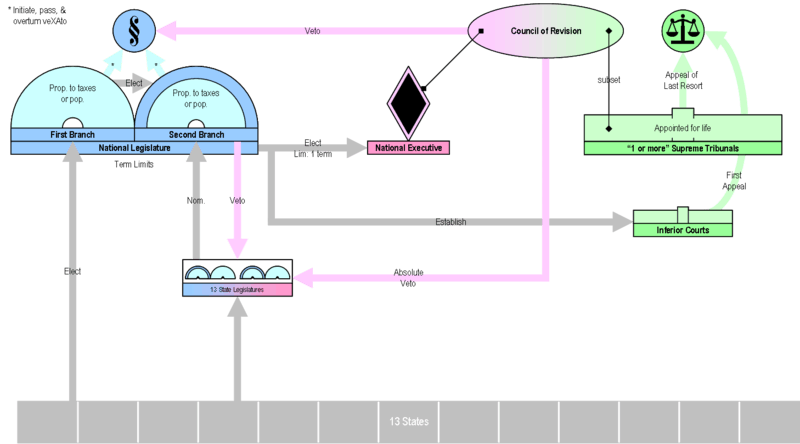

While waiting for the Convention to formally begin, Madison sketched out his initial proposal, which became known as the Virginia Plan and reflected his views as a strong nationalist. The Virginia and Pennsylvania delegates agreed with Madison's plan and formed what came to be the predominant coalition within the Convention.[38] The plan was modeled on the state governments and was written in the form of fifteen resolutions outlining basic principles. It lacked the system of checks and balances that would become central to the US Constitution.[39] It called for a supreme national government and was a radical departure from the Articles of Confederation.[40] On May 29, Edmund Randolph, the governor of Virginia, presented the Virginia Plan to the Convention.[41]

The same day, Charles Pinckney of South Carolina introduced his own plan that also greatly increased the power of the national government; however, the supporters of the Virginia Plan ensured that it, rather than Pinckney's plan, received the most consideration.[42] Many of Pinckney's ideas did appear in the final draft of the Constitution. His plan called for a bicameral legislature made up of a House of Delegates and a Senate. The popularly elected House would elect senators who would serve for four year terms and represent one of four regions. The national legislature would have veto power over state laws. The legislature would elect a chief executive called a president. The president and his cabinet would have veto power over legislation. The plan also included a national judiciary.[43]

On May 30, the Convention agreed, at the request of Gouverneur Morris, "that a national government ought to be established consisting of a supreme Legislative, Executive and Judiciary".[44] This was the Convention's first move towards going beyond its mandate merely to amend the Articles of Confederation and instead produce an entirely new government.[45] Once it had agreed to the idea of a supreme national government, the Convention began debating specific parts of the Virginia Plan.

Congress

The Virginia Plan called for the unicameral Confederation Congress to be replaced with a bicameral Congress. This would be a truly national legislature with power to make laws "in all cases to which the separate states are incompetent".[46] It would also be able to veto state laws. Representation in both houses of Congress would be apportioned according either to "quotas of contribution" (a state's wealth as reflected in the taxes it paid) or the size of each state's non-slave population. The lower house of Congress would be directly elected by the people, while the upper house would be elected by the lower house from candidates nominated by state legislatures.[47]

Proportional representation

Immediately after agreeing to form a supreme national government, the delegates turned to the Virginia Plan's proposal for proportional representation in Congress.[48] Virginia, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, which were the largest states by population, were unhappy with the one vote per state rule in the Confederation Congress since combined they had almost half the nation's population but could be outvoted by the smaller states.[49] Nevertheless, the delegates were divided over the best way to apportion representatives. Quotas of contribution appealed to southern delegates because they would include slave property, but Rufus King of Massachusetts highlighted the impractical side of such a scheme. If the national government did not impose direct taxes (which for the next century it almost never did), he noted, representatives could not be assigned. Calculating such quotas would also be difficult due to lack of reliable data. Basing representation on the number of "free inhabitants" was unpopular with delegates from the South, where forty percent of the population was enslaved.[50] In addition, the small states were opposed to any change that decreased their own influence. Delaware's delegation threatened to leave the Convention if proportional representation replaced equal representation, so debate on apportionment was postponed.[51]

On June 9, William Paterson of New Jersey reminded the delegates that they were sent to Philadelphia to revise the Articles of Confederation, not to establish a national government. While he agreed that the Confederation Congress needed new powers, including the power to coerce the states, he was adamant that a confederation required equal representation for states.[52] James Madison records his words as follows:[53]

[The Articles of the Confederation] were therefore the proper basis of all the proceedings of the Convention. We ought to keep within its limits, or we should be charged by our constituents with usurpation . . . the Commissions under which we acted were not only the measure of our power. [T]hey denoted also the sentiments of the States on the subject of our deliberation. The idea of a national [Government] as contradistinguished from a federal one, never entered into the mind of any of them, and to the public mind we must accommodate ourselves. We have no power to go beyond the federal scheme, and if we had the people are not ripe for any other. We must follow the people; the people will not follow us.

Bicameralism and elections

—James Madison, as recorded by Robert Yates, Tuesday June 26, 1787[54]

On May 31, the delegates discussed the structure of Congress and how its members would be selected. The division of the legislature into an upper and lower house was familiar and had wide support. The British Parliament had an elected House of Commons and a hereditary House of Lords. All the states had bicameral legislatures except for Pennsylvania.[55] The delegates quickly agreed that each house of Congress should be able to originate bills. They also agreed that the new Congress would have all the legislative powers of the Confederation Congress and veto power over state laws.[56]

There was some opposition to popular election of the lower house or House of Representatives. Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts and Roger Sherman of Connecticut feared the people were too easily misled by demagogues and that popular election could lead to mob rule and anarchy. Pierce Butler of South Carolina believed that only wealthy men of property could be trusted with political power. The majority of the Convention, however, supported popular election.[57] George Mason of Virginia said the lower house was "to be the grand depository of the democratic principle of the government."[58]

There was general agreement that the upper house or Senate should be smaller and more selective than the lower house. Its members should be gentlemen drawn from the most intelligent and virtuous among the citizenry.[59] Experience had convinced the delegates that such an upper house was necessary to tame the excesses of the democratically elected lower house.[55] The Virginia Plan's method of selecting the Senate was more controversial. Members concerned with preserving state power wanted state legislatures to select senators, while James Wilson of Pennsylvania proposed direct election by the people.[60] It was not until June 7 that the delegates unanimously decided that state legislatures would choose senators.[61]

Three-Fifths ratio

On the question of proportional representation, the three large states still faced opposition from the eight small states. James Wilson realized that the large states needed the support of the Deep South states of Georgia and the Carolinas. For these southern delegates, the main priority was protection of slavery.[62] Working with John Rutledge of South Carolina, Wilson proposed the Three-Fifths Compromise on June 11. This resolution apportioned seats in the House of Representatives on the basis of a state's free population plus three-fifths of its slave population. Nine states voted in favor, with only New Jersey and Delaware against.[63] This compromise would give the South at least a dozen additional congressmen and electoral college votes.[64] That same day, the large-state/slave-state alliance also succeeded in applying the three-fifths ratio to Senate seats (though this was later overturned).[65]

Executive branch

As English law had typically recognized government as having two separate functions—law making embodied in the legislature and law executing embodied in the king and his courts—the division of the legislature from the executive and judiciary was a natural and uncontested point.[24] Even so, the form the executive should take, its powers and its selection would be sources of constant dispute through the summer of 1789.[66] At the time, few nations had nonhereditary executives that could serve as models. The Dutch Republic was led by a stadtholder, but this office was in practice inherited by members of the House of Orange. The Swiss Confederacy had no single leader, and the elective monarchies of the Holy Roman Empire and Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth were viewed as corrupt.[67]

As a result of their colonial experience, Americans distrusted a strong chief executive. Under the Articles of Confederation, the closest thing to an executive was the Committee of the States, which was empowered to transact government business while Congress was in recess. However, this body was largely inactive. The revolutionary state constitutions made the governors subordinate to the legislatures, denying them executive veto power over legislation. Without veto power, governors were unable to block legislation that threatened minority rights.[68] States chose governors in different ways. Many state constitutions empowered legislatures to select them, but several allowed direct election by the people. In Pennsylvania, the people elected an executive council and the legislature appointed one of its members to be chief executive.[67]

The Virginia Plan proposed a national executive chosen by Congress. It would have power to execute national laws and be vested with the power to make war and treaties.[69] Whether the executive would be a single person or a group of people was not defined.[70] The executive together with a "convenient number" of federal judges would form a Council of Revision with the power to veto any act of Congress. This veto could be overridden by an unspecified number of votes in both houses of Congress.[69]

Unitary executive

James Wilson feared that the Virginia Plan made the executive too dependent on Congress. He argued that there should be a single, unitary executive. Members of a multiple executive would most likely be chosen from different regions and represent regional interests. In Wilson's view, only a single executive could represent the nation as a whole while giving "energy, dispatch, and responsibility" to the government.[71]

Wilson used his understanding of civic virtue as defined by the Scottish Enlightenment to help design the presidency. The challenge was to design a properly constituted executive that was fit for a republic and based on civic virtue by the general citizenry. He spoke 56 times calling for a chief executive who would be energetic, independent, and accountable. He believed that the moderate level of class conflict in American society produced a level of sociability and inter-class friendships that could make the presidency the symbolic leader of the entire American people. Wilson did not consider the possibility of bitterly polarized political parties. He saw popular sovereignty as the cement that held America together linking the interests of the people and of the presidential administration. The president should be a man of the people who embodied the national responsibility for the public good and provided transparency and accountability by being a highly visible national leader, as opposed to numerous largely anonymous congressmen.[72][73][74]

On June 1, Wilson proposed that "the Executive consist of a single person." This motion was seconded by Charles Pinckney, whose plan called for a single executive and specifically named this official a "president".[71] Roger Sherman objected in favor of something similar to a parliamentary system in which the executive should be appointed by and directly accountable to the legislature. Edmund Randolph agreed with Wilson that the executive needed "vigor", but he disapproved of a unitary executive, which he feared was "the foetus of monarchy".[75] Randolph and George Mason led the opposition against a unitary executive, but most delegates agreed with Wilson. The prospect that George Washington would be the first president may have allowed the proponents of a unitary executive to accumulate a large coalition. Wilson's motion for a single executive passed on June 4.[76] Initially, the convention set the executive's term of office to seven years, but this would be revisited.[77]

Election, removal and the veto

Wilson also argued that the executive should be directly elected by the people. Only through direct election could the executive be independent of both Congress and the states.[78] This view was unpopular. A few delegates such as Roger Sherman, Elbridge Gerry and Pierce Butler opposed direct election of the executive because they considered the people too easily manipulated. However, most delegates did not question the intelligence of the voters, rather what concerned them was the slowness by which information spread in the late 18th century. Due to a lack of information, the average voter would be too ignorant about the candidates to make an informed decision.[79]

A majority of delegates favored the president's election by Congress for a seven-year term; though there was concern that this would give the legislature too much power. Southern delegates supported selection by state legislatures, but this was opposed by nationalists such as Madison who feared that such a president would become a power broker between different state interests rather than a symbol of national unity. Realizing that direct election was impossible, Wilson proposed what would become the electoral college—the states would be divided into districts in which voters would choose electors who would then elect the president. This would preserve the separation of powers and keep the state legislatures out of the selection process. Initially, however, this scheme received little support.[80]

The issue was one of the last major issues to be resolved, and was done so in the electoral college. At the time, before the formation of modern political parties, there was widespread concern that candidates would routinely fail to secure a majority of electors in the electoral college. The method of resolving this problem therefore was a contested issue. Most thought that the House of Representatives should then choose the president, since it most closely reflected the will of the people. This caused dissension among delegates from smaller states, who realized that this would put their states at a disadvantage. To resolve this dispute, the Convention agreed that the House would elect the president if no candidate had an electoral college majority, but that each state delegation would vote as a bloc, rather than individually.[77]

The Virginia Plan made no provision for removing the executive. On June 2, John Dickinson of Delaware proposed that the president be removed from office by Congress at the request of a majority of state legislatures. Madison and Wilson opposed this state interference in the national executive branch. Sherman argued that Congress should be able to remove the president for any reason in what was essentially a vote of no-confidence. George Mason worried that would make the president a "mere creature of the legislature" and violate separation of powers. Dickinson's motion was rejected, but in the aftermath of the vote there was still no consensus over how an unfit president should be removed from office.[81]

On June 4, the delegates debated the Council of Revision. Wilson and Alexander Hamilton of New York disagreed with the mixing of executive and judicial branches. They wanted the president to have an absolute veto to guarantee his independence from the legislative branch. Remembering how colonial governors used their veto to "extort money" from the legislature, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania opposed giving the president an absolute veto. Gerry proposed that a two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress be able to overrule any veto of the Council of Revision. This was amended to replace the council with the president alone, but Madison insisted on retaining a Council of Revision and consideration of the veto power was postponed.[82]

The office of Vice President was also included later in the deliberations, mainly to provide the president a successor if he was unable to complete his term but also to provide presidential electors with an incentive to vote for at least one out of state candidate in addition to a "favorite son" from their own state or region.

Judiciary

In the English tradition, judges were seen as being agents of the king and his court, who represented him throughout his realm. Madison believed that in the American states, this direct link between state executives and judges was a source of corruption through patronage, and thought the link had to be severed between the two, thus creating the "third branch" of the judiciary which had been without any direct precedent before this point.[24]

On June 4, delegates unanimously agreed to a national judiciary "of one supreme tribunal and one or more inferior tribunals". The delegates disagreed on how federal judges should be chosen. The Virginia Plan called for the national legislature to appoint judges. James Wilson wanted the president to appoint judges to increase the power of that office.[83]

On June 13, the revised report on the Virginia Plan was issued. This report summarized the decisions made by the delegates in the first two weeks of the Convention. It was agreed that a "national judiciary be established, to consist of one supreme tribunal". Congress would have the power to create and appoint inferior courts. Judges were to hold office "during good behavior", and the Senate would appoint them.[84]

Alternative plans

The small state delegates were alarmed at the plan taking shape: a supreme national government that could override state laws and proportional representation in both houses of Congress.[85] William Paterson and other delegates from New Jersey, Connecticut, Maryland and New York created an alternative plan that consisted of several amendments to the Articles of Confederation. Under the New Jersey Plan, as it was called, the Confederation Congress would remain unicameral with each state having one vote. Congress would be allowed to levy tariffs and other taxes as well as regulate trade and commerce. Congress would elect a plural "federal executive" whose members would serve a single term and could be removed by Congress at the request of a majority of state governors. There would also be a federal judiciary to apply US law. Federal judges would serve for life and be appointed by the executives. Laws enacted by Congress would take precedence over state laws. This plan was introduced on June 15.[86][87][43]

On June 18, Alexander Hamilton of New York presented his own plan that was at odds with both the Virginia and New Jersey plans. It called for the constitution to be modeled on the British government. The bicameral legislature included a lower house called the Assembly elected by the people for three year terms. The people would choose electors who would elect the members of a Senate who served for life. Electors would also choose a single executive called the governor who would also serve for life. The governor would have an absolute veto over bills. There would also be a national judiciary whose members would serve for life. Hamilton called for the abolition of the states (or at least their reduction to sub-jurisdictions with limited powers). Some scholars have suggested that Hamilton presented this radical plan in order to help secure passage of the Virginia Plan by making it seem moderate by comparison. The plan was so out of step with political reality that it was not even debated, and Hamilton would be troubled for years by accusations that he was a monarchist.[88][43]

On June 19, the delegates voted on the New Jersey Plan. With the support of the slave states and Connecticut, the large states were able to defeat the plan by a 7–3 margin. Maryland's delegation was divided, so it did not vote.[89] This did not end the debate over representation. Rather, the delegates found themselves in a stalemate that lasted into July.

On several occasions, the Connecticut delegation—Roger Sherman, Oliver Ellsworth and William Samuel Johnson—proposed a compromise that the House would have proportional representation and the Senate equal representation.[90] A version of this compromise had originally been crafted and proposed by Sherman on June 11. He agreed with Madison that the Senate should be composed of the wisest and most virtuous citizens, but he also saw its role as defending the rights and interests of the states.[91] James Madison recorded Sherman's June 11 speech as follows:[92]

Mr. Sherman proposed that the proportion of suffrage in the 1st branch should be according to the respective numbers of free inhabitants; and that in the second branch or Senate, each State should have one vote and no more. He said as the States would remain possessed of certain individual rights, each State ought to be able to protect itself: otherwise a few large States will rule the rest. The House of Lords in England he observed had certain particular rights under the Constitution, and hence they have an equal vote with the House of Commons that they may be able to defend their rights.

On June 29, Johnson made a similar point: "that in one branch, the people ought to be represented; in the other, the states."[93] Neither side was ready yet to embrace the concept of divided sovereignty between the states and a federal government, however.[94] The distrust between large and small state delegates had reached a low point, exemplified by comments made on June 30 by Gunning Bedford Jr. As reported by Robert Yates, Bedford stated:[95]

I do not, gentlemen, trust you. If you possess the power, the abuse of it could not be checked; and what then would prevent you from exercising it to our destruction? . . . Yes, sir, the larger states will be rivals but not against each other—they will be rivals against the rest of the states . . . Will you crush the smaller states, or must they be left unmolested? Sooner than be ruined, there are foreign powers who will take us by the hand.

Compromising on apportionment

Grand Committee

As the Convention was entering its second full month of deliberations, it was decided that further consideration of the prickly question of how to apportion representatives in the national legislature should be referred to a committee composed of one delegate from each of the eleven states that were present at that time at the Convention. The members of this "Grand Committee," as it has come to be known, included William Paterson of New Jersey, Robert Yates of New York, Luther Martin of Maryland, Gunning Bedford, Jr. of Delaware, Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut, Abraham Baldwin of Georgia, Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, George Mason of Virginia, William Davie of North Carolina, John Rutledge of South Carolina and Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania.[96] The committee's composition heavily favored the smaller states, as even the large state delegates tended to be more moderate.[97]

While the Convention took a three-day recess in observance of the Fourth of July holiday, the Grand Committee began its work.[97] Franklin proposed and the committee adopted a compromise similar to the Connecticut plan. Membership in the House would be apportioned by population, with members elected from districts of forty thousand people. Each state would have an equal vote in the Senate. To gain large state support, however, Franklin proposed that the House of Representatives have exclusive power to originate bills concerned with raising money or government salaries (this would become the Origination Clause).[98] This compromise has become known as the Great Compromise or the Connecticut Compromise.[99]

Revisiting the three-fifths ratio

The committee presented its report on July 5, but the compromise was not immediately adopted by the Convention. For the next eleven days, the Convention stalled as delegates attempted to gain as many votes for their states as possible.[100] On July 6, a five-man committee was appointed to allocate specific numbers of representatives to each state. It called for a 56–member House of Representatives and used "[t]he number of blacks and whites with some regard to supposed wealth" as a basis of allocating representatives to each state. The Northern states had 30 representatives while the Southern states had 26. Delegates from non-slave states objected to counting slaves as they could not vote.[101][102]

On July 9, a new committee was chosen to reconsider the allocation of representatives. This time there were eleven members, one from each state. It recommended a 65–member House with allocation of representatives based on the number of free inhabitants and three-fifths of slaves. Under this new scheme, Northern states had 35 representatives and the South had 30. Southern delegates protested the North's greater representation and argued that their growing populations had been underestimated. The Committee of Eleven's report was approved, but the divergent interests of the Northern and Southern states remained obstacles to reaching consensus.[102]

On July 10, Edmund Randolph called for a regular census on which to base future reallocation of House seats.[103] During the debate on the census, South Carolina delegates Pierce Butler and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney sought to replace the three-fifths ratio with a full count of the slave population. They argued that slave property contributed to the wealth of the Southern states and as such should be used in calculating representation. This irritated Northern delegates who were already reluctant to support the three-fifths compromise. James Wilson, one of the authors of the three-fifths compromise, asked, "Are slaves to be admitted as Citizens? Then why are they not admitted on an equality with White Citizens? Are they admitted as property? Then why is not other property admitted into the computation?"[104]

After fierce debate, the delegates voted to apportion representation and direct taxation based on all white inhabitants and three-fifths of the slave population. This formula would apply to the existing states as well as any states created in the future. The first census would occur six years after the new federal government began operations and every ten years afterwards.[105]

Great Compromise

On July 14, John Rutledge and James Wilson attempted to secure proportional representation in the Senate. Charles Pinckney proposed a form of semi-proportional representation in which the smaller states would gain more representation than under a completely proportional system. This proposal was defeated.[106]

In a close vote on July 16, the Convention adopted the Great Compromise as recommended by the Grand Committee. Nationalist delegates remained bitterly opposed, however, until on July 23 they succeeded in further modifying the compromise to give members of the Senate individual voting power, rather than having votes taken by each state's representatives en bloc, as had occurred in Congress under the Articles of Confederation.[107] This accomplished the nationalist goal of preventing state governments from having a direct say in Congress's choice to make national laws.[108] The final document was thus a mixture of Madison's original "national" constitution and the desired "federal" Constitution that many of the delegates sought.[109]

Further debate

Federal supremacy

On July 17, the delegates worked to define the powers of Congress. The Virginia Plan asserted the supremacy of the national government, giving Congress authority "to legislate in all cases to which the separate States are incompetent" and stating that congressional legislation would take precedence over conflicting state laws. In a motion introduced by Gunning Bedford, the Convention approved this provision with only South Carolina and Georgia voting against. Four small states—Connecticut, New Jersey, Delaware and Maryland—accepted the expansion of congressional power. Later in life, Madison explained that this was a result of the Great Compromise. Once the small states were assured they would be represented in the new government, they "exceeded all others in zeal" for a strong national government.[110]

The Virginia Plan also gave Congress veto power over state laws. Madison believed this provision was crucial to prevent the states from engaging in irresponsible behavior, such as had occurred under the Confederation government. Gouverneur Morris feared the congressional veto would alienate states that might otherwise support the Constitution. Luther Martin argued that it would be too impractical and time-consuming, asking "Shall the laws of the states be sent up to the general legislature before they shall be permitted to operate?"[111]

The Convention rejected the congressional veto. In its place, Martin proposed language taken from the New Jersey Plan that was unanimously approved by the Convention: "that the Legislative acts of the US made by virtue and pursuance of the articles of Union, and all treaties made and ratified under the authority of the US shall be the supreme law of the respective States . . . and that the . . . States shall be bound thereby in their decisions".[112]

Appointing judges

Needing a break from discussing the presidency, the delegates once again considered the judicial branch on July 18. They were still divided over the method of appointment. Half of the Convention wanted the Senate to choose judges, while the other half wanted the president to do it. Luther Martin supported Senate appointment because he thought that body's members would defend the interests of the individual states.[113]

Nathaniel Gorham had suggested a compromise—appointment by the president with the "advice and consent of the Senate". While the meaning of "advice and consent" was still undefined, the proposal gained some support. On July 21, Madison offered an alternative compromise—the president would appoint judges but the Senate could veto an appointment by a two-thirds majority. This proposal would have made it very hard for the Senate to block judicial appointments. Madison's proposal failed to garner support, and the delegates ended by reaffirming that the Senate would appoint judges.[114]

On July 21, Wilson and Madison tried unsuccessfully to revive Madison's council of revision. While judges had a role in reviewing the constitutionality of laws, argued Gorham, mixing the policy judgments of the president with the legal judgments of a court would violate separation of powers. John Rutledge agreed, saying "judges ought never to give their opinion on a law till it comes before them".[115]

First draft

The Convention adjourned from July 26 to August 6 to await the report of the Committee of Detail, which was to produce a first draft of the Constitution. It was chaired by John Rutledge, with the other members including Edmund Randolph, Oliver Ellsworth, James Wilson, and Nathaniel Gorham.

Though the committee did not record minutes of its proceedings, three key surviving documents offer clues to the committee's handiwork: an outline by Randolph with edits by Rutledge, extensive notes and a second draft by Wilson, also with Rutledge's edits, and the committee's final report to the Convention.[116]:168 From this evidence it is thought that the committee used the original Virginia Plan, the decisions of the Convention on modifications to that plan, and other sources, such as the Articles of Confederation, provisions of the state constitutions, and even Charles Pinckney's plan, to produce the first full draft,[117][116]:165 which author David O. Stewart has called a "remarkable copy-and-paste job."[116]:165

Randolph adopted two rules in preparing his initial outline: that the Constitution should only include essential principles, avoiding minor provisions that would change over time, and that it should be stated in simple and precise language.[118]

Much of what was included in the committee's report consisted of numerous details that the Convention had never discussed but which the committee correctly viewed as uncontroversial and unlikely to be challenged; and as such, much of the committee's proposal would ultimately be incorporated into the final version of the Constitution without debate.[116]:169 Examples of these details included the Speech and Debate Clause, which grants members of Congress immunity for comments made in their jobs, and the rules for organizing the House of Representatives and the Senate.

However, Rutledge, himself a former state governor, was determined that while the new national government should be stronger than the Confederation government had been, the national government's power over the states should not be limitless; and at Rutledge's urging, the committee went beyond what the Convention had proposed. As Stewart describes it, the committee "hijacked" and remade the Constitution, altering critical agreements the Convention delegates had already made, enhancing the powers of the states at the expense of the national government, and adding several far-reaching provisions that the Convention had never discussed.[116]:165

The first major change, insisted on by Rutledge, was meant to sharply curtail the essentially unlimited powers to legislate "in all cases for the general interests of the Union" that the Convention only two weeks earlier had agreed to grant the Congress. Rutledge and Randolph worried that the broad powers implied in the language agreed on by the Convention would have given the national government too much power at the expense of the states. In Randolph's outline the committee replaced that language with a list of 18 specific "enumerated" powers, many adopted from the Articles of Confederation, that would strictly limit the Congress' authority to measures such as imposing taxes, making treaties, going to war, and establishing post offices.[119][116]:170–71 Rutledge, however, was not able to completely convince all of the members of the committee to accept the change. Over the course of a series of drafts, a catchall provision (the "Necessary and Proper Clause") was eventually added, most likely by Wilson, a nationalist little concerned with the sovereignty of individual states, giving the Congress the broad power "to make all Laws that shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers, and all other powers vested by this Constitution in the government of the United States, or in any department or officer thereof."[120][116]:171–72 Another revision of Wilson's draft also placed eight specific limits on the states, such as barring them from independently entering into treaties and from printing their own money, providing a certain degree of balance to the limits on the national government intended by Rutledge's list of enumerated powers.[121][116]:172 In addition, Wilson's draft modified the language of the Supremacy Clause adopted by the Convention, to ensure that national law would take precedence over inconsistent state laws.[116]:172

These changes set the final balance between the national and state governments that would be entered into the final document, as the Convention never challenged this dual-sovereignty between nation and state that had been fashioned by Rutledge and Wilson.[116]:172

Another set of radical changes introduced by the Committee of Detail proved far more contentious when the committee's report was presented to the Convention. On the day the Convention had agreed to appoint the committee, Southerner Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, of South Carolina, had warned of dire consequences should the committee fail to include protections for slavery in the Southern states, or allow for taxing of Southern agricultural exports.[122][116]:173 Pinckney and his fellow Southern delegates must have been delighted to see that the committee had included three provisions that explicitly restricted the Congress' authority in ways favorable to Southern interests. The proposed language would bar the Congress from ever interfering with the slave trade. It would also prohibit taxation of exports, and would require that any legislation concerning regulation of foreign commerce through tariffs or quotas (that is, any laws akin to England's "Navigation Acts") pass only with two-thirds majorities of both houses of Congress. While much of the rest of the committee's report would be accepted without serious challenge on the Convention floor, these last three proposals would provoke outrage from Northern delegates and slavery opponents.[123][116]:173–74

The final report of the committee, which became the first draft of the Constitution, was the first workable constitutional plan, as Madison's Virginia Plan had simply been an outline of goals and a broad structure. Even after it issued this report, the committee continued to meet off and on until early September.

Further modifications and concluding debate

Another month of discussion and relatively minor refinement followed, during which several attempts were made to alter the Rutledge draft, though few were successful. Some wanted to add property qualifications for people to hold office, while others wanted to prevent the national government from issuing paper money.[116]:187 Madison in particular wanted to push the Constitution back in the direction of his Virginia plan.

One important change that did make it into the final version included the agreement between northern and southern delegates to empower Congress to end the slave trade starting in 1808. Southern and northern delegates also agreed to strengthen the Fugitive Slave Clause in exchange for removing a requirement that two-thirds of Congress agree on "navigation acts" (regulations of commerce between states and foreign governments). The two-thirds requirement was favored by southern delegates, who thought Congress might pass navigation acts that would be economically harmful to slaveholders.[116]:196

Once the Convention had finished amending the first draft from the Committee of Detail, a new set of unresolved questions were sent to several different committees for resolution. The Committee of Detail was considering several questions related to habeas corpus, freedom of the press, and an executive council to advise the president. Two committees addressed questions related to the slave trade and the assumption of war debts.

A new committee was created, the Committee on Postponed Parts, to address other questions that had been postponed. Its members, such as Madison, were delegates who had shown a greater desire for compromise and were chosen for this reason as most in the Convention wanted to finish their work and go home.[116]:207 The committee dealt with questions related to the taxes, war making, patents and copyrights, relations with indigenous tribes, and Franklin's compromise to require money bills to originate in the House. The biggest issue they addressed was the presidency, and the final compromise was written by Madison with the committee's input.[116]:209 They adopted Wilson's earlier plan for choosing the president by an electoral college, and settled on the method of choosing the president if no candidate had an electoral college majority, which many such as Madison thought would be "nineteen times out of twenty".

The committee also shortened the president's term from seven years to four years, freed the president to seek re-election after an initial term, and moved impeachment trials from the courts to the Senate. They also created the office of the vice president, whose only roles were to succeed a president unable to complete a term of office, to preside over the Senate, and to cast tie-breaking votes in the Senate. The committee transferred important powers from the Senate to the president, for example the power to make treaties and appoint ambassadors.[116]:212 One controversial issue throughout much of the Convention had been the length of the president's term, and whether the president was to be term limited. The problem had resulted from the understanding that the president would be chosen by Congress; the decision to have the president be chosen instead by an electoral college reduced the chance of the president becoming beholden to Congress, so a shorter term with eligibility for re-election became a viable option.

Near the end of the Convention, Gerry, Randolph, and Mason emerged as the main force of opposition. Their fears were increased as the Convention moved from Madison's vague Virginia Plan to the concrete plan of Rutledge's Committee of Detail.[116]:235 Some have argued that Randolph's attacks on the Constitution were motivated by political ambition, in particular his anticipation of possibly facing rival Patrick Henry in a future election. The main objection of the three was the compromise that would allow Congress to pass "navigation acts" with a simple majority in exchange for strengthened slave provisions.[116]:236 Among their other objections was an opposition to the office of vice president.

Though most of their complaints did not result in changes, a couple did. Mason succeeded in adding "high crimes and misdemeanors" to the impeachment clause. Gerry also convinced the Convention to include a second method for ratification of amendments. The report out of the Committee of Detail had included only one mechanism for constitutional amendment, in which two-thirds of the states had to ask Congress to convene a convention for consideration of amendments. Upon Gerry's urging, the Convention added back the Virginia Plan's original method whereby Congress would propose amendments that the states would then ratify.[116]:238 All amendments to the Constitution, save the 21st amendment, have been made through this latter method.

Despite their successes, these three dissenters grew increasingly unpopular as most other delegates wanted to bring the Convention's business to an end and return home. As the Convention was drawing to a conclusion, and delegates prepared to refer the Constitution to the Committee on Style to pen the final version, one delegate raised an objection over civil trials. He wanted to guarantee the right to a jury trial in civil matters, and Mason saw in this a larger opportunity. Mason told the Convention that the constitution should include a bill of rights, which he thought could be prepared in a few hours. Gerry agreed, though the rest of the committee overruled them. They wanted to go home, and thought this was nothing more than another delaying tactic.[116]:241

Few at the time realized how important the issue would become, with the absence of a bill of rights becoming the main argument of the anti-Federalists against ratification. Most of the Convention's delegates thought that states already protected individual rights, and that the Constitution did not authorize the national government to take away rights, so there was no need to include protections of rights. Once the Convention moved beyond this point, the delegates addressed a couple of last-minute issues. Importantly, they modified the language that required spending bills to originate in the House of Representatives and be flatly accepted or rejected, unmodified, by the Senate. The new language empowered the Senate to modify spending bills proposed by the House.[116]:243

Drafting and signing

Once the final modifications had been made, the Committee of Style and Arrangement was appointed "to revise the style of and arrange the articles which had been agreed to by the house." Unlike other committees, whose members were named so the committees included members from different regions, this final committee included no champions of the small states. Its members were mostly in favor of a strong national government and unsympathetic to calls for states' rights.[116]:229–30 They were William Samuel Johnson (Connecticut), Alexander Hamilton (New York), Gouverneur Morris (Pennsylvania), James Madison (Virginia), and Rufus King (Massachusetts). On Wednesday, September 12, the report of the "committee of style" was ordered printed for the convenience of the delegates. For three days, the Convention compared this final version with the proceedings of the Convention. The Constitution was then ordered engrossed on Saturday, September 15 by Jacob Shallus, and was submitted for signing on September 17. It made at least one important change to what the Convention had agreed to; King wanted to prevent states from interfering in contracts. Although the Convention never took up the matter, his language was now inserted, creating the contract clause.[116]:243

Gouverneur Morris is credited, both now and then, as the chief draftsman of the final document, including the stirring preamble. Not all the delegates were pleased with the results; thirteen left before the ceremony, and three of those remaining refused to sign: Edmund Randolph of Virginia, George Mason of Virginia, and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts. George Mason demanded a Bill of Rights if he was to support the Constitution. The Bill of Rights was not included in the Constitution submitted to the states for ratification, but many states ratified the Constitution with the understanding that a bill of rights would soon follow.[124] Shortly before the document was to be signed, Gorham proposed to lower the size of congressional districts from 40,000 to 30,000 citizens. A similar measure had been proposed earlier, and failed by one vote. George Washington spoke up here, making his only substantive contribution to the text of the Constitution in supporting this move. The Convention adopted it without further debate. Gorham would sign the document, although he had openly doubted whether the United States would remain a single, unified nation for more than 150 years.[116]:112 Ultimately, 39 of the 55 delegates who attended (74 had been chosen from 12 states) ended up signing, but it is likely that none were completely satisfied. Their views were summed up by Benjamin Franklin, who said, "I confess that there are several parts of this Constitution which I do not at present approve, but I am not sure I shall never approve them. ... I doubt too whether any other Convention we can obtain, may be able to make a better Constitution. ... It therefore astonishes me, Sir, to find this system approaching so near to perfection as it does; and I think it will astonish our enemies ..."[125]

Rhode Island never sent delegates, and two of New York's three delegates did not stay at the Convention for long. Therefore, as George Washington stated, the document was executed by "eleven states, and Colonel Hamilton."[116]:244 Washington signed the document first, and then moving by state delegation from north to south, as had been the custom throughout the Convention, the delegates filed to the front of the room to sign their names.

At the time the document was signed, Franklin gave a persuasive speech involving an anecdote on a sun that was painted on the back of Washington's Chippendale chair.[127] As recounted in Madison's notes:

Whilst the last members were signing it Doctor. Franklin looking towards the Presidents Chair, at the back of which a rising sun happened to be painted, observed to a few members near him, that Painters had found it difficult to distinguish in their art a rising from a setting sun. I have said he, often and often in the course of the Session, and the vicissitudes of my hopes and fears as to its issue, looked at that behind the President without being able to tell whether it was rising or setting: But now at length I have the happiness to know that it is a rising and not a setting Sun.[127][128]

The Constitution was then submitted to the states for ratification, pursuant to its own Article VII.[129]

Slavery

Slavery was one of the most difficult issues confronting the delegates. Slavery was widespread in the states at the time of the Convention.[116]:68 At least a third of the Convention's 55 delegates owned slaves, including all of the delegates from Virginia and South Carolina.[116]:68–69 Slaves comprised approximately one-fifth of the population of the states,[130]:139 and apart from northernmost New England, where slavery had largely been eliminated, slaves lived in all regions of the country.[130]:132 However, more than 90% of the slaves[130]:132 lived in the South, where approximately 1 in 3 families owned slaves (in the largest and wealthiest state, Virginia, that figure was nearly 1 in 2 families).[130]:135 The entire agrarian economy of the South was based on slave labor, and the Southern delegates to the Convention were unwilling to accept any proposal that they believed would threaten the institution.

Commerce and Slave Trade Compromise

Whether slavery was to be regulated under the new Constitution was a matter of such intense conflict between the North and South that several Southern states refused to join the Union if slavery were not to be allowed. Delegates opposed to slavery were forced to yield in their demands that slavery be completely outlawed within the new nation. However, they continued to argue that the Constitution should prohibit the states from participating in the international slave trade, including in the importation of new slaves from Africa and the export of slaves to other countries. The Convention postponed making a final decision on the international slave trade until late in the deliberations because of the contentious nature of the issue. During the Convention's late July recess, the Committee of Detail had inserted language that would prohibit the federal government from attempting to ban international slave trading and from imposing taxes on the purchase or sale of slaves. The Convention could not agree on these provisions when the subject came up again in late August, so they referred the matter to an eleven-member committee for further discussion. This committee helped work out a compromise: Congress would have the power to ban the international slave trade, but not for another twenty years (that is, not until 1808). In exchange for this concession, the federal government's power to regulate foreign commerce would be strengthened by provisions that allowed for taxation of slave trades in the international market and that reduced the requirement for passage of navigation acts from two-thirds majorities of both houses of Congress to simple majorities.[131]

Three-Fifths Compromise

Another contentious slavery-related question was whether slaves would be counted as part of the population in determining representation of the states in the Congress, or would instead be considered property and as such not be considered for purposes of representation.[132] Delegates from states with a large population of slaves argued that slaves should be considered persons in determining representation, but as property if the new government were to levy taxes on the states on the basis of population.[132] Delegates from states where slavery had become rare argued that slaves should be included in taxation, but not in determining representation.[132] Finally, delegate James Wilson proposed the Three-Fifths Compromise.[43] This was eventually adopted by the Convention.

Framers of the Constitution

Fifty-five delegates attended sessions of the Constitutional Convention, and are considered the Framers of the Constitution, although only 39 delegates actually signed.[133][134] The states had originally appointed 70 representatives to the Convention, but a number of the appointees did not accept or could not attend, leaving 55 who would ultimately craft the Constitution.[133]

Almost all of the 55 Framers had taken part in the Revolution, with at least 29 having served in the Continental forces, most in positions of command.[135] All but two or three had served in colonial or state government during their careers.[136] The vast majority (about 75%) of the delegates were or had been members of the Confederation Congress, and many had been members of the Continental Congress during the Revolution.[116]:25 Several had been state governors.[136][135] Just two delegates, Roger Sherman and Robert Morris, would be signatories to all three of the nation's founding documents: the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution.[135]

More than half of the delegates had trained as lawyers (several had even been judges), although only about a quarter had practiced law as their principal means of business. There were also merchants, manufacturers, shippers, land speculators, bankers or financiers, two or three physicians, a minister, and several small farmers.[137][135] Of the 25 who owned slaves, 16 depended on slave labor to run the plantations or other businesses that formed the mainstay of their income. Most of the delegates were landowners with substantial holdings, and most, with the possible exception of Roger Sherman and William Few, were very comfortably wealthy.[138] George Washington and Robert Morris were among the wealthiest men in the entire country.[135]

Their depth of knowledge and experience in self-government was remarkable. As Thomas Jefferson in Paris semi-seriously wrote to John Adams in London, "It really is an assembly of demigods."[139][140]

Delegates used two streams of intellectual tradition, and any one delegate could be found using both or a mixture depending on the subject under discussion: foreign affairs, the economy, national government, or federal relationships among the states.

- Connecticut

- Oliver Ellsworth*

- William Samuel Johnson

- Roger Sherman

- Delaware

- Richard Bassett

- Gunning Bedford, Jr.

- Jacob Broom

- John Dickinson

- George Read

- Georgia

- Abraham Baldwin

- William Few

- William Houstoun*

- William Pierce*

- Maryland

- Daniel Carroll

- Luther Martin*

- James McHenry

- John Francis Mercer*

- Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer

- Massachusetts

- Elbridge Gerry*

- Nathaniel Gorham

- Rufus King

- Caleb Strong*

- New Hampshire

- Nicholas Gilman

- John Langdon

- New Jersey

- David Brearley

- Jonathan Dayton

- William Houston*

- William Livingston

- William Paterson

- New York

- Alexander Hamilton

- John Lansing Jr.*

- Robert Yates*

- North Carolina

- William Blount

- William Richardson Davie*

- Alexander Martin*

- Richard Dobbs Spaight

- Hugh Williamson

- Pennsylvania

- George Clymer

- Thomas Fitzsimons

- Benjamin Franklin

- Jared Ingersoll

- Thomas Mifflin

- Gouverneur Morris

- Robert Morris

- James Wilson

- South Carolina

- Pierce Butler

- Charles Cotesworth Pinckney

- Charles Pinckney

- John Rutledge

- Virginia

- John Blair

- James Madison

- George Mason*

- James McClurg*

- Edmund Randolph*

- George Washington

- George Wythe*

- Rhode Island

- Rhode Island did not send delegates to the Convention.

(*) Did not sign the final draft of the U.S. Constitution. Randolph, Mason, and Gerry were the only three present in Philadelphia at the time who refused to sign.

Several prominent Founders are notable for not participating in the Constitutional Convention. Thomas Jefferson was abroad, serving as the minister to France.[141] John Adams was in Britain, serving as minister to that country, but he wrote home to encourage the delegates. Patrick Henry refused to participate because he "smelt a rat in Philadelphia, tending toward the monarchy." Also absent were John Hancock and Samuel Adams. Many of the states' older and more experienced leaders may have simply been too busy with the local affairs of their states to attend the Convention,[136] which had originally been planned to strengthen the existing Articles of Confederation, not to write a constitution for a completely new national government.

In popular culture

- The 1989 film A More Perfect Union, which portrays the events and discussions of the Constitutional Convention, was largely filmed in Independence Hall.

- In the 2015 Broadway musical Hamilton, Alexander Hamilton's proposal of his own plan during the Constitutional Convention was featured in the song "Non-Stop", which concluded the first act.

See also

- Constitution Day (United States)

- Convention to propose amendments to the United States Constitution

- The Federalist Papers

- History of the United States Constitution

- National Constitution Center

- Syng inkstand

- Timeline of drafting and ratification of the United States Constitution

- United States Bill of Rights

References

Notes

- Jillson 2009, p. 31.

- Odesser-Torpey 2013, p. 26.

- Rossiter 1987.

- Wood 1998, pp. 155–156.

- Klarman 2016, pp. 13–14.

- Van Cleve 2017, p. 1.

- Larson & Winship 2005, p. 4.

- Van Cleve 2017, pp. 4–5.

- Larson & Winship 2005, p. 5.

- Klarman 2016, p. 41.

- Klarman 2016, p. 47.

- Klarman 2016, pp. 20–21.

- Beeman 2009, p. 15.

- Klarman 2016, pp. 21–23.

- Klarman 2016, p. 34.

- Klarman 2016, pp. 74–88.

- Richards 2003, pp. 132–139.

- Palumbo 2009, pp. 9–10.

- Kaminski & Leffler 1991, p. 3.

- Larson & Winship 2005, p. 6.

- "Observing Constitution Day". archives.gov. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. August 21, 2016. Archived from the original on August 17, 2019.

- Moehn 2003, p. 37.

- Larson & Winship 2005, p. 103.

- Padover & Landynski 1995.

- Larson & Winship 2005, p. 83.

- Stewart 2007, p. 51.

- Beeman 2009, p. 82.

- Larson & Winship 2005, p. 11.

- History Alive! Pursuing American Ideals. Rancho Cordova, CA: Teachers' Curriculum Institute. April 2013. p. 56.

- Larson & Winship 2005, pp. 162–64.

- "Madison at the Federal Convention". founders.archives.gov. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- Klarman 2016, p. 129.

- Stewart 2007, p. 29.

- Beeman 2009, p. 27.

- Klarman 2016, p. 128.

- Klarman 2016, p. 130.

- Klarman 2016, p. 131–132.

- Beeman 2009, p. 52.

- Stewart 2007, p. 53.

- Beeman 2009, p. 91.

- Beeman 2009, p. 86.

- Beeman 2009, p. 99.

- Mount 2012.

- Beeman 2009, p. 102.

- Beeman 2009, pp. 102–104.

- Klarman 2016, p. 139.

- Klarman 2016, p. 139-140.

- Beeman 2009, p. 105.

- Stewart 2007, pp. 56, 66.

- Stewart 2007, pp. 56-58, 77.

- Beeman 2009, p. 109.

- Beeman 2009, p. 149.

- Farrand 1911, p. 178.

- Farrand 1911, p. 431.

- Beeman 2009, pp. 89, 110.

- Beeman 2009, p. 121.

- Beeman 2009, pp. 110–116.

- Beeman 2009, p. 117.

- Beeman 2009, p. 122.

- Beeman 2009, p. 119.

- Stewart 2007, pp. 64-65.

- Stewart 2007, p. 67.

- Stewart 2007, pp. 75-78.

- Stewart 2007, p. 79.

- Stewart 2007, p. 80.

- Beeman 2009, p. 124.

- Stewart 2007, p. 154.

- Beeman 2009, p. 125–126.

- Klarman 2016, p. 140.

- Beeman 2009, p. 90.

- Beeman 2009, p. 127.

- Taylor & Hardwick 2009, pp. 331–346..

- McCarthy 1987, pp. 689–696.

- DiClerico 1987, pp. 301–317.

- Beeman 2009, p. 128.

- Beeman 2009, pp. 128, 134.

- Beeman 2009, p. 136.

- Beeman 2009, p. 129.

- Beeman 2009, p. 130.

- Beeman 2009, pp. 135-136.

- Beeman 2009, pp. 141-142.

- Beeman 2009, pp. 138-140.

- Beeman 2009, p. 236.

- Beeman 2009, p. 159.

- Stewart 2007, p. 88.

- Beeman 2009, pp. 161-162.

- Stewart 2007, pp. 90-91.

- Stewart 2007, pp. 94-95.

- Stewart 2007, p. 96.

- Beeman 2009, p. 164.

- Beeman 2009, p. 150.

- Farrand 1911, p. 196.

- Beeman 2009, p. 181.

- Beeman 2009, p. 173.

- Farrand 1911, pp. 500–501.

- Beeman 2009, p. 200.

- Stewart 2007, p. 110.

- Beeman 2009, p. 201.

- Stewart 2007, p. 111.

- Stewart 2007, p. 115.

- Stewart 2007, pp. 116–117.

- Beeman 2009, p. 208.

- Stewart 2007, p. 118.

- Beeman 2009, pp. 209–210.

- Beeman 2009, pp. 211–213.

- Stewart 2007, pp. 123–124.

- Farrand, Max, ed. (1911). The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, Volume 2. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 94–95.

- See Laurence Claus, Power Enumeration and the Silences of Constitutional Federalism http://ssrn.com/abstract=2837390

- Beeman 2009, p. 199.

- Beeman 2009, pp. 227–228.

- Beeman 2009, p. 228.

- Beeman 2009, p. 229.

- Beeman 2009, p. 237.

- Beeman 2009, p. 238.

- Beeman 2009, pp. 237–238.

- Stewart, David O. (2007). The Summer of 1787. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-8692-3.

- Beeman 2009, pp. 269–70.

- Beeman 2009, p. 270.

- Beeman 2009, pp. 273–74.

- Beeman 2009, p. 274.

- Beeman 2009, pp. 274–75.

- Beeman 2009, pp. 269, 275.

- Beeman 2009, p. 275.

- National Archives (October 30, 2015). "Bill of Rights". Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- Speech of Benjamin Franklin – The U_S_ Constitution Online – USConstitution_net

- United States Postage Stamps

- "Rising Sun" in The Constitutional Convention of 1787: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of America's Founding, Vol. 1 (ed. John R. Vile: ABC-CLIO, 2005), p. 681.

- Madison Notes for September 17, 1787.

- Akhil Reed Amar (2006). America's Constitution: A Biography. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-8129-7272-6.

- United States Department of Labor and Commerce Bureau of the Census (1909). A Century of Population Growth: From the First Census of the United States to the Twelfth, 1790–1900. D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- Beeman 2009, pp. 318–29.

- Constitutional Rights Foundation. "The Constitution and Slavery". Archived from the original on February 25, 2004. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- "Meet the Framers of the Constitution". America's Founding Documents. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. 2017. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017.

- Rodell, Fred (1986). 55 Men: The Story of the Constitution, Based on the Day-by-Day Notes of James Madison. Stackpole Books. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-8117-4409-6.

- "The Founding Fathers: A Brief Overview". The Charters of Freedom. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. October 30, 2015. Archived from the original on October 6, 2016.

- Beeman 2009, p. 65.

- Beeman 2009, pp. 65–68.

- Beeman 2009, pp. 66–67.

- Webb, Derek A. "Doubting a little of one's infallibility: The real miracle at Philadelphia – National Constitution Center". National Constitution Center – constitutioncenter.org. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- Jefferson, Thomas. "Letter of Thomas Jefferson to John Adams, August 30, 1787". The Library of Congress. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- Farrand 1913, p. 13.

Sources

- Beeman, Richard (2009). Plain Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6570-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bowen, Catherine Drinker (1966). Miracle At Philadelphia: The Story of the Constitutional Convention. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0316103985.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- DiClerico, Robert E. (Spring 1987). "James Wilson's Presidency". Presidential Studies Quarterly. Center for the Study of the Presidency and Congress. 17 (2): 301–317. JSTOR 40574453.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Farrand, Max (1913). The Framing of the Constitution of the United States. New Haven: Yale University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)