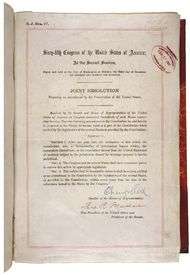

Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Eighteenth Amendment (Amendment XVIII) of the United States Constitution established the prohibition of the powers in the United States. The amendment was proposed by Congress on December 18, 1917, and was ratified by the requisite number of states on January 16, 1919. The Eighteenth Amendment was repealed by the Twenty-first Amendment on December 5, 1933.

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States of America |

|---|

|

|

Preamble and Articles of the Constitution |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

|

| Unratified Amendments |

|

| History |

| Full text of the Constitution and Amendments |

|

The Eighteenth Amendment was the product of decades of efforts by the temperance movement, which held that a ban on the sale of alcohol would ameliorate poverty and other societal issues. The Eighteenth Amendment declared the production, transport, and sale of intoxicating liquors illegal, though it did not outlaw the actual consumption of alcohol. Shortly after the amendment was ratified, Congress passed the Volstead Act to provide for the federal enforcement of Prohibition. The Volstead Act declared that liquor, wine, and beer all qualified as intoxicating liquors and were therefore prohibited. Under the terms of the Eighteenth Amendment, Prohibition began on January 17, 1920, one year after the amendment was ratified.

Although the Eighteenth Amendment led to a decline in alcohol consumption in the United States, nationwide enforcement of Prohibition proved difficult, particularly in cities. Organized crime and other groups engaged in large-scale bootlegging, and speakeasies became popular in many areas. Public sentiment began to turn against Prohibition during the 1920s, and 1932 Democratic presidential nominee Franklin D. Roosevelt called for the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment in his platform. The Twenty-first Amendment repealed the Eighteenth Amendment in 1933, making the Eighteenth Amendment the only amendment to the U.S. Constitution to date to be repealed in its entirety.

Text

Section 1. After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all the territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited.

Section 2. The Congress and the several States shall have concurrent power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Section 3. This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by the legislatures of the several States, as provided in the Constitution, within seven years from the date of the submission hereof to the States by the Congress.

Background

The Eighteenth Amendment was the result of decades of effort by the temperance movement in the United States and at the time was generally considered a progressive amendment.[1] Starting in 1906, the Anti-Saloon League (ASL) began leading a campaign to ban the sale of alcohol on a state level. They led speeches, advertisements, and public demonstrations, claiming that banning the sale of alcohol would get rid of poverty and social issues, such as immoral behavior and violence. It would also inspire new forms of sociability between men and women and they believed that families would be happier, fewer industrial mistakes would be made and overall, the world would be a better place.[2] Other groups such as the Women's Christian Temperance Union began as well trying to ban the sale, manufacturing, and distribution of alcoholic beverages.[2] A well-known reformer during this time period was Carrie Amelia Moore Nation, whose violent actions (such as vandalizing saloon property) made her a household name across America.[3] Many state legislatures had already enacted statewide prohibition prior to the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment but did not ban the consumption of alcohol in most households. It took some states longer than others to ratify this amendment, especially northern states, including New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts. They violated the law by still allowing some wines and beers to be sold.[2] By 1916, 23 of 48 states had already passed laws against saloons, some even banning the manufacture of alcohol in the first place.[3]

The Temperance Movement

The Temperance Movement was dedicated to the complete abstinence of alcohol from public life. The movement began in the early 1800s within Christian churches, and was very religiously motivated. The central areas within which the group was founded included the Saratoga area of New York, as well as parts of Massachusetts. Churches were also highly influential in gaining new members and support, garnering 6,000 local societies in several different states.[4]

A group that was inspired by the movement was the Anti-Saloon League, who at the turn of the 20th century began heavily lobbying for prohibition in the United States. The group was founded in 1893 in the state of Ohio, gaining massive support from Evangelical Protestants, to becoming a national organization in 1895. The group was successful in helping implement prohibition, through heavy lobbying and having a vast influence. Following the repeal of prohibition, the group fell out of power, and in 1950 it merged with other groups, forming the National Temperance League.[5]

Proposal and ratification

On August 1, 1917, the Senate passed a resolution containing the language of the amendment to be presented to the states for ratification. The vote was 65 to 20, with the Democrats voting 36 in favor and 12 in opposition; and the Republicans voting 29 in favor and 8 in opposition. The House of Representatives passed a revised resolution[6] on December 17, 1917. This was the first amendment to impose a date by which it had to be ratified or else the amendment would be discarded.[7]

In the House, the vote was 282 to 128, with the Democrats voting 141 in favor and 64 in opposition; and the Republicans voting 137 in favor and 62 in opposition. Four Independents in the House voted in favor and two Independents cast votes against the amendment.[8] It was officially proposed by the Congress to the states when the Senate passed the resolution, by a vote of 47 to 8, the next day, December 18.[9]

The amendment and its enabling legislation did not ban the consumption of alcohol, but made it difficult to obtain alcoholic beverages legally, as it prohibited the sale, manufacture and distribution of them in U.S. territory. Any one who got caught selling, manufacturing or distributing alcoholic beverages would be arrested.[2] Because prohibition was already implemented by many states, it was quickly ratified into a law.[7] The ratification of the Amendment was completed on January 16, 1919, when Nebraska became the 36th of the 48 states then in the Union to ratify it. On January 29, acting Secretary of State Frank L. Polk certified the ratification.[10]

The following states ratified the amendment:[11]

- Mississippi (January 7, 1918)

- Virginia (January 11, 1918)

- Kentucky (January 14, 1918)

- North Dakota (January 25, 1918)[note 1]

- South Carolina (January 29, 1918)

- Maryland (February 13, 1918)

- Montana (February 19, 1918)

- Texas (March 4, 1918)

- Delaware (March 18, 1918)

- South Dakota (March 20, 1918)

- Massachusetts (April 2, 1918)

- Arizona (May 24, 1918)

- Georgia (June 26, 1918)

- Louisiana (August 3, 1918)[note 2]

- Florida (November 27, 1918)

- Michigan (January 2, 1919)

- Ohio (January 7, 1919)

- Oklahoma (January 7, 1919)

- Idaho (January 8, 1919)

- Maine (January 8, 1919)

- West Virginia (January 9, 1919)

- California (January 13, 1919)

- Tennessee (January 13, 1919)

- Washington (January 13, 1919)

- Arkansas (January 14, 1919)

- Illinois (January 14, 1919)

- Indiana (January 14, 1919)

- Kansas (January 14, 1919)

- Alabama (January 15, 1919)

- Colorado (January 15, 1919)

- Iowa (January 15, 1919)

- New Hampshire (January 15, 1919)

- Oregon (January 15, 1919)

- North Carolina (January 16, 1919)

- Utah (January 16, 1919)

- Nebraska (January 16, 1919)

- Missouri (January 16, 1919)

- Wyoming (January 16, 1919)

- Minnesota (January 17, 1919)

- Wisconsin (January 17, 1919)

- New Mexico (January 20, 1919)

- Nevada (January 21, 1919)

- New York (January 29, 1919)

- Vermont (January 29, 1919)

- Pennsylvania (February 25, 1919)

- New Jersey (March 9, 1922)

The following states rejected the amendment:

.jpg)

To define the language used in the Amendment, Congress enacted enabling legislation called the National Prohibition Act, better known as the Volstead Act, on October 28, 1919. President Woodrow Wilson vetoed that bill, but the House of Representatives immediately voted to override the veto and the Senate voted similarly the next day. The Volstead Act set the starting date for nationwide prohibition for January 17, 1920, which was the earliest date allowed by the 18th amendment.[15]

The Volstead Act

This act was conceived and introduced by Wayne Wheeler, a leader of the Anti-Saloon League, a group which found alcohol responsible for almost all of society's problems and which also ran many campaigns against the sale of alcohol.[16] The law was also heavily supported by then-Judiciary Chairman Andrew Volstead from Minnesota, and was named in his honor. The act in its written form laid the groundwork of prohibition, defining the procedures for banning the distribution of alcohol including their production and distribution.[17]

Volstead had once before introduced an early version of the law to Congress. It was first brought to the floor on May 27, 1919, where it met heavy resistance from Democratic senators. Instead, the so-called "wet law" was introduced, an attempt to end the wartime prohibition laws put into effect much earlier. The debate over prohibition would rage for that entire session, as the House was divided among what would become known as the "bone-drys" and the "wets". Because Republicans held the majority of the House of Representatives, the Volstead Act finally passed on July 22, 1919, with 287 in favor and 100 opposed.

However, the act was largely a failure, proving unable to prevent mass distribution of alcoholic beverages and also inadvertently causing a massive increase in organized crime.[18] The act would go on to define the terms and enforcement methods of prohibition, until the passing of the 21st amendment in 1933 effectively repealed it.

Controversies

The proposed amendment was the first to contain a provision setting a deadline for its ratification.[19] That clause of the amendment was challenged, with the case reaching the US Supreme Court. It upheld the constitutionality of such a deadline in Dillon v. Gloss (1921). The Supreme Court also upheld the ratification by the Ohio legislature in Hawke v. Smith (1920), despite a petition requiring that the matter go to ballot.

This was not the only controversy around the amendment. The phrase "intoxicating liquor" would not logically have included beer and wine (as they are not distilled), and their inclusion in the prohibition came as a surprise to the general public, as well as wine and beer makers. This controversy caused many Northern states to not abide by the amendment, which caused some problems.[2] The brewers were probably not the only Americans to be surprised at the severity of the regime thus created. Voters who considered their own drinking habits blameless, but who supported prohibition to discipline others, also received a rude shock. That shock came with the realization that federal prohibition went much farther in the direction of banning personal consumption than all local prohibition ordinances and many state prohibition statutes. National Prohibition turned out to be quite a different beast than its local and state cousins.

Under Prohibition, the illegal manufacture and sale of liquor–known as "bootlegging"–occurred on a large scale across the United States. In urban areas, where the majority of the population opposed Prohibition, enforcement was generally much weaker than in rural areas and smaller towns. Perhaps the most dramatic consequence of Prohibition was the effect it had on organized crime in the United States: as the production and sale of alcohol went further underground, it began to be controlled by the Mafia and other gangs, who transformed themselves into sophisticated criminal enterprises that reaped huge profits from the illicit liquor trade.

When it came to its booming bootleg business, the Mafia became skilled at bribing police and politicians to look the other way. Chicago's Al Capone emerged as the most notorious example of this phenomenon, earning an estimated $60 million annually from the bootlegging and speakeasy operations he controlled. In addition to bootlegging, gambling and prostitution reached new heights during the 1920s as well. A growing number of Americans came to blame Prohibition for this widespread moral decay and disorder–despite the fact that the legislation had intended to do the opposite–and to condemn it as a dangerous infringement on the freedom of the individual.[20]

In his important study both of the Eighteenth Amendment and its repeal, Daniel Okrent identifies the powerful political coalition that worked successfully in the two decades leading to the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment:

Five distinct, if occasionally overlapping, components made up this unspoken coalition: racists, progressives, suffragists, populists (whose ranks included a small socialist auxiliary), and nativists. Adherents of each group may have been opposed to alcohol for its own sake, but used the Prohibition impulse to advance ideologies and causes that had little to do with it.[21]

Calls for repeal

If public sentiment had turned against Prohibition by the late 1920s, the Great Depression only hastened its demise, as some argued that the ban on alcohol denied jobs to the unemployed and much-needed revenue to the government. The efforts of the nonpartisan group Americans Against Prohibition Association (AAPA) added to public disillusionment. In 1932, the platform of Democratic presidential candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt included a plank for repealing the 18th Amendment, and his victory that November marked a certain end to Prohibition.

In February 1933, Congress adopted a resolution proposing the Twenty-first Amendment, which repealed the 18th Amendment and modified the Volstead Act to permit the sale of beer. The resolution required state conventions, rather than the state legislatures, to approve the amendment, effectively reducing the process to a one-state, one-vote referendum rather than a popular vote contest. That December, Utah became the 36th state to ratify the amendment, achieving the necessary majority for repeal. A few states continued statewide prohibition after 1933, but by 1966 all of them had abandoned it. Since then, liquor control in the United States has largely been determined at the local level.[20]

Impact

Just after the Eighteenth Amendment's adoption, there was a significant reduction in alcohol consumption among the general public and particularly among low-income groups. There were fewer hospitalizations for alcoholism and likewise fewer liver-related medical problems. However, consumption soon climbed as underworld entrepreneurs began producing "rotgut" alcohol which was full of dangerous diseases.[3] With the rise of home distilled alcohol, careless distilling led to the deaths of many citizens. During the ban upwards of 10,000 deaths can be attributed to wood alcohol (methanol) poisoning.[22] Ultimately, during prohibition use and abuse of alcohol ended up higher than before it started.[23][24]

Though there were significant increases in crimes involved in the production and distribution of illegal alcohol, there was an initial reduction in overall crime, mainly in types of crimes associated with the effects of alcohol consumption such as public drunkenness.[25] Those who continued to use alcohol, tended to turn to organized criminal syndicates. Law enforcement wasn't strong enough to stop all liquor traffic; however, they used "sting" operations, such as Prohibition agent Eliot Ness famously using wiretapping to discern secret locations of breweries.[2] The prisons became crowded which led to fewer arrests for the distribution of alcohol, as well as those arrested being charged with small fines rather than prison time.[2] The murder rate fell for two years, but then rose to record highs because this market became extremely attractive to criminal organizations, a trend that reversed the very year prohibition ended.[25] The homicide rate increased from 6 per 100,000 population in the pre-Prohibition period to nearly 10 per 100,000 in 1933. That rising trend was reversed by the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, and the rate continued to decline throughout the 1930s and early 1940s.[26] Overall, crime rose 24%, including increases in assault and battery, theft, and burglary.[27]

Anti-prohibition groups were formed and worked to have the Eighteenth Amendment repealed, which was done by adoption of the Twenty-first Amendment on December 5, 1933.[28]

Bootlegging and organized crime

Following ratification in 1919, the amendment's effects were long lasting, leading to increases in crime in many large cities in the United States, like Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles.[29] Along with this came many separate forms of illegal alcohol distribution. Examples of this include speakeasies and bootlegging, as well as illegal distilling operations.

Bootlegging got its start in towns bordering Mexico and Canada, as well as in areas with several ports and harbors, a favorite distribution area for bootleggers being Atlantic City, New Jersey. The alcohol was often supplied from various foreign distributors, like Cuba and the Bahamas, or even Newfoundland and islands under rule by the French.

The government in response employed the Coast Guard to search and detain any ships transporting alcohol into the ports, but with this came several complications such as disputes over where jurisdiction lay on the water. This was what made Atlantic City such a hot spot for smuggling operations, because of a shipping point nearly three miles off shore that U.S. officials could not investigate, further complicating enforcement of the amendment. What made matters even worse for the Coast Guard was that they were not well equipped enough to chase down bootlegging vessels. The Coast Guard however, was able to respond to these issues, and began searching vessels out at sea, instead of when they made port, and upgraded their own vehicles allowing for more efficient and consistent arrests.

But even with those advancements in enforcing the amendment, there were still complications that plagued the government's efforts. One issue came in the form of forged prescriptions for alcoholic beverages. Many forms of alcohol were being sold over the counter at the time, under the guise of being for medical purposes. But in truth, these beverages had falsified the evidence that they were medically fit to be sold to consumers.

Bootlegging itself was the leading factor that developed the organized crime-rings in big cities, given that controlling and distributing liquor was a very difficult task to achieve. From that arose many profitable gangs that would control every aspect of the distribution process, whether it be concealed brewing and storage, operating a speakeasy, or selling in restaurants and nightclubs run by a specific syndicate. With organized crime becoming a rising problem in the United States, control of specific territories was a key objective among gangs, leading to many violent confrontations; as a result, murder rates and burglaries heavily increased between 1920 and 1933.[29] Bootlegging was also found to be a gateway crime for many gangs, who would then expand operations into crimes such as prostitution, gambling rackets, narcotics, loan-sharking, extortion and labor rackets, thus causing problems to persist long after the amendment was repealed.

See also

- Dry county

Notes

- Effective January 28, 1918, the date on which the North Dakota ratification was approved by the state Governor.

- Effective August 9, 1918, the date on which the Louisiana ratification was approved by the state Governor.

References

- Hamm, Richard F. (1995). Shaping the Eighteenth Amendment: temperance reform, legal culture, and the polity, 1880–1920. UNC Press Books. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-8078-4493-9. OCLC 246711905.

- "User account - Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History". Gilderlehrman.org. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- "18th and 21st Amendments - Facts & Summary - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com.

- "Temperance Movement". Britannica.com. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- "Anti-Saloon League". Britannica.com. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- 40 Stat. 1050

- "Understanding the 18th Amendment". Laws.com. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- David Pietrusza, 1920: The Year of Six Presidents (NY: Carroll & Graf, 2007), 160

- "Prohibition wins in Senate, 47 to 8" (PDF). New York Times. December 19, 1917. p. 6.

- 40 Stat. 1941

- The dates of proposal, ratifications and certification come from The Constitution Of The United States Of America Analysis And Interpretation Analysis Of Cases Decided By The Supreme Court Of The United States To July 1, 2014, United States Senate doc. no. 108-17, at 35 n.10.

- Cohn, Henry S.; Davis, Ethan (2009). "Stopping the Wind that Blows and the Rivers that Run: Connecticut and Rhode Island Reject the Prohibition Amendment". Quinnipiac Law Review. 27: 327, 328.

[I]t took until 1922 for the forty-sixth state, New Jersey, to ratify, and Connecticut and Rhode Island would never do so.

– via HeinOnline (subscription required) - New York Times: "Connecticut Balks at Prohibition," February 5, 1919, accessed July 27, 2011

- New York Times: "Rhode Island Defeats Prohibition," March 13, 1918, accessed July 27, 2011

- "Woodrow Wilson - U.S. Presidents - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com.

- Smentkowski, Brian P. (August 22, 2017). ""Eighteenth Amendment."". Britannica.com. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- "The Volstead Act". History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- "Congress enforces prohibition." History.com, A&E Television Networks, www.history.com/this-day-in-history/congress-enforces-prohibition.

- "18th and 21st Amendments - Facts & Summary - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- "The 18th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution". National Constitution Center – The 18th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- Rothman, Lily (January 14, 2015). "The History of Poisoned Alcohol Includes an Unlikely Culprit: The U.S. Government". Time. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- "Prohibition: Unintended Consequences | PBS". Pbs.org.

- Blum, Deborah (February 18, 2010). The Poisoners Handbook. New York, New York: Penguin Books. p. Ch. 2.

- "Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 157 : Alcohol Prohibition Was a Failure" (PDF). Object.cato.org. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- "Prohibition = Violence". Reason.com. January 29, 2003. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- Histeropedia - The Eighteenth Amendment’s Contribution to Increased Crime and Societal Disobedience in the 1920s (Fall 2012)

Rather than reducing the crime rates within the United States, prohibition resulted in an increased crime rate of 24% including increased assault and battery by 13%, homicide rates by 12.7%, and burglaries and theft by 9%. - Roosevelt, Franklin (December 5, 1933),

- "Prohibition and the Rise of the American Gangster". Prologue.blogs.archives.gov. January 17, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2019.