Twenty-second Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Twenty-second Amendment (Amendment XXII) to the United States Constitution sets a limit on the number of times an individual is eligible for election to the office of President of the United States, and also sets additional eligibility conditions for presidents who succeed to the unexpired terms of their predecessors.[1]

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States of America |

|---|

|

|

Preamble and Articles of the Constitution |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

|

| Unratified Amendments |

|

| History |

| Full text of the Constitution and Amendments |

|

Prior to the ratification of the amendment, the president had not been subject to term limits, but George Washington had established a two-term tradition that many other presidents had followed. In the 1940 presidential election and the 1944 presidential election, Franklin D. Roosevelt became the first president to win a third term and then later a fourth term, giving rise to concerns about the potential issues involved with a president serving an unlimited number of terms. Congress approved the Twenty-second Amendment on March 24, 1947, and submitted it to the state legislatures for ratification. That process was completed on February 27, 1951, after the amendment had been ratified by the requisite 36 of the then-48 states (as neither Alaska nor Hawaii had been admitted as states), and its provisions came into force on that date.

The amendment prohibits any individual who has been elected president twice from being elected again. Under the amendment, an individual who fills an unexpired presidential term lasting greater than two years is also prohibited from winning election as president more than once. Scholars debate whether the amendment prohibits affected individuals from succeeding to the presidency under any circumstances or whether it only applies to presidential elections.

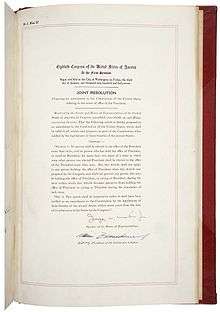

Text

Section 1. No person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice, and no person who has held the office of President, or acted as President, for more than two years of a term to which some other person was elected President shall be elected to the office of the President more than once. But this Article shall not apply to any person holding the office of President when this Article was proposed by the Congress, and shall not prevent any person who may be holding the office of President, or acting as President, during the term within which this Article becomes operative from holding the office of President or acting as President during the remainder of such term.

Section 2. This Article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by the legislatures of three-fourths of the several states within seven years from the date of its submission to the states by the Congress.[2]

Background

Notwithstanding that the Twenty-second Amendment was clearly a reaction to Franklin D. Roosevelt's election to an unprecedented four terms as president, the notion of presidential term limits has long been debated in American politics. Delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 considered the issue extensively (alongside broader questions, such as who would elect the president, and the president's role). Many—including Alexander Hamilton and James Madison—supported a lifetime appointment for presidents, while others favored fixed terms appointments. Virginia's George Mason denounced the life-tenure proposal as tantamount to establishment of an elective monarchy.[3] An early draft of the United States Constitution provided that the President was restricted to a single seven-year term.[4] Ultimately, the Framers approved four-year terms with no restriction on the amount of time a person could serve as president.

Though dismissed by the Constitutional Convention, the concept of term limits for U.S. presidents took hold during the presidencies of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. As his second term entered its final year in 1796, George Washington was exhausted from years of public service, and his health had begun to decline. He was also bothered by the unrelenting attacks from his political opponents, which had escalated after the signing of the Jay Treaty, and believed that he had accomplished his major goals as president. For these reasons, he decided not to stand for reelection to a third term, a decision he announced to the nation through a Farewell Address in September 1796.[5] Eleven years later, as Thomas Jefferson neared the half-way point of his second term, he wrote,

If some termination to the services of the chief magistrate be not fixed by the Constitution, or supplied by practice, his office, nominally for years, will in fact, become for life; and history shows how easily that degenerates into an inheritance.[6]

Since Washington made his historic announcement, numerous academics and public figures have looked at his decision to retire after two terms, and have, according to political scientist Bruce Peabody, "argued he had established a two-term tradition that served as a vital check against any one person, or the presidency as a whole, accumulating too much power".[7] Numerous amendments aimed toward changing informal precedent into constitutional law were proposed in Congress during the early to mid-19th century, but none passed.[3][8] Three of the next four presidents after Jefferson—James Madison, James Monroe, and Andrew Jackson—served two terms, and each one adhered to the two-term principle;[1] Martin Van Buren was the only president between Jackson and Abraham Lincoln to be nominated for a second term, although he lost the 1840 election, and so only served one term.[8] Before the Civil War the seceding States drafted the Constitution of the Confederate States of America which in most respects was similar to the United States Constitution, but one change was limiting the President to a single six-year term.

In spite of the strong two-term tradition, a few presidents prior to Franklin Roosevelt did attempt to secure a third term. Following Ulysses S. Grant's reelection victory in 1872, there were serious discussions within Republican political circles about the possibility of his running again in 1876. Interest in a third term for Grant evaporated however, in the light of negative public opinion and opposition from members of Congress, and Grant left the presidency in 1877, after two terms. Even so, as the 1880 election approached, he sought nomination for a (non-consecutive) third term at the 1880 Republican National Convention, but narrowly lost to James Garfield, who would go on to win the 1880 election.[8]

Theodore Roosevelt succeeded to the presidency on September 14, 1901, following William McKinley's assassination (194 days into his second term), and was subsequently elected to a full term in 1904. While he declined to seek a third (second full) term in 1908, Roosevelt did seek one four years later, in the election of 1912, where he lost to Woodrow Wilson. Wilson himself, despite his ill health following a serious stroke, aspired to a third term. Many of Wilson's advisers tried to convince him that his health precluded another campaign, but Wilson nonetheless asked that his name be placed in nomination for the presidency at the 1920 Democratic National Convention.[9] Democratic Party leaders were unwilling to support Wilson, however, and the nomination eventually went to James M. Cox, who lost to Warren G. Harding. Wilson again contemplated running for a (nonconsecutive) third term in 1924, devising a strategy for his comeback, but again lacked any support; he died in February of that year.[10]

Franklin D. Roosevelt spent the months leading up to the 1940 Democratic National Convention refusing to state whether he would seek a third term. His Vice President, John Nance Garner, along with Postmaster General James Farley, announced their candidacies for the Democratic nomination. When the convention came, Roosevelt sent a message to the convention, saying he would run only if drafted, saying delegates were free to vote for whomever they pleased. This message was interpreted to mean he was willing to be drafted, and he subsequently was renominated on the convention's first ballot.[8][11] Later, during the 1940 presidential election, Roosevelt won a decisive victory over Republican Wendell Willkie, becoming the first, and to date only, president to exceed eight years in office. Roosevelt's decision to seek a third term dominated the election campaign.[12] Willkie ran against the open-ended presidential tenure, while Democrats cited the war in Europe as a reason for breaking with precedent.[8]

Four years later, Roosevelt faced Republican Thomas E. Dewey in the 1944 election. Near the end of the campaign, Thomas Dewey announced his support of a constitutional amendment that would limit future presidents to two terms. According to Dewey, "four terms, or sixteen years (a direct reference to the president's tenure in office four years hence), is the most dangerous threat to our freedom ever proposed."[13] He also discreetly raised the issue of the president's age. Roosevelt, however, was able to exude enough energy and charisma to retain the confidence of the American public, who reelected him to a fourth term.[14]

While he effectively quelled rumors of his poor health during the campaign, Roosevelt's health was in reality deteriorating. On April 12, 1945, only 82 days after his fourth inauguration, he suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and died. He was succeeded by Vice President Harry Truman.[15] In the midterm elections 18 months later, Republicans took control of both the House and the Senate. As many of them had campaigned on the issue of presidential tenure, declaring their support for a constitutional amendment that would limit how long a person could serve as president, the issue was given top priority in the 80th Congress when it convened in January 1947.[7]

Proposal and ratification

Proposal in Congress

The House of Representatives took quick action, approving a proposed constitutional amendment (House Joint Resolution 27) setting a limit of two four-year terms for future presidents. Introduced by Earl C. Michener, the measure passed 285–121, with support from 47 Democrats, on February 6, 1947. Meanwhile, the Senate developed its own proposed amendment, which initially differed from the House proposal by requiring that the amendment be submitted to state ratifying conventions for ratification, rather than to the state legislatures, and by prohibiting any person who had served more than 365 days in each of two terms from further presidential service. Both these provisions were removed when the full Senate took up the bill, but a new provision was, however, added. Put forward by Robert A. Taft, it clarified procedures governing the number of times a vice president who succeeded to the presidency might be elected to office. The amended proposal was passed 59–23, with 16 Democrats in favor, on March 12.[1][16]

Several days later, the House agreed to the Senate's revisions, and on March 24, 1947, the constitutional amendment imposing term limitations on future Presidents was submitted to the states for ratification.[2] The ratification process for the 22nd Amendment was completed on February 27, 1951, 3 years, 343 days after it was sent to the states.[12][17]

Ratification by the states

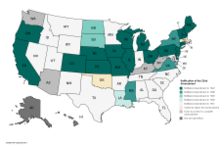

Once submitted to the states, the 22nd Amendment was ratified by:[2]

- Maine (March 31, 1947)

- Michigan (March 31, 1947)

- Iowa (April 1, 1947)

- Kansas (April 1, 1947)

- New Hampshire (April 1, 1947)

- Delaware (April 2, 1947)

- Illinois (April 3, 1947)

- Oregon (April 3, 1947)

- Colorado (April 12, 1947)

- California (April 15, 1947)

- New Jersey (April 15, 1947)

- Vermont (April 15, 1947)

- Ohio (April 16, 1947)

- Wisconsin (April 16, 1947)

- Pennsylvania (April 29, 1947)

- Connecticut (May 21, 1947)

- Missouri (May 22, 1947)

- Nebraska (May 23, 1947)

- Virginia (January 28, 1948)

- Mississippi (February 12, 1948)

- New York (March 9, 1948)

- South Dakota (January 21, 1949)

- North Dakota (February 25, 1949)

- Louisiana (May 17, 1950)

- Montana (January 25, 1951)

- Indiana (January 29, 1951)

- Idaho (January 30, 1951)

- New Mexico (February 12, 1951)

- Wyoming (February 12, 1951)

- Arkansas (February 15, 1951)

- Georgia (February 17, 1951)

- Tennessee (February 20, 1951)

- Texas (February 22, 1951)

- Utah (February 26, 1951)

- Nevada (February 26, 1951)

- Minnesota (February 27, 1951)

Ratification was completed when the Minnesota Legislature ratified the amendment. On March 1, 1951, the Administrator of General Services, Jess Larson, issued a certificate proclaiming the 22nd Amendment duly ratified and part of the Constitution. The amendment was subsequently ratified by:[2] - North Carolina (February 28, 1951)

- South Carolina (March 13, 1951)

- Maryland (March 14, 1951)

- Florida (April 16, 1951)

- Alabama (May 4, 1951)

Conversely, two states—Oklahoma and Massachusetts—rejected the amendment, while five (Arizona, Kentucky, Rhode Island, Washington, and West Virginia) took no action.[16]

Affected individuals

The 22nd Amendment's two-term limit did not apply (due to the grandfather clause in Section 1) to Harry S. Truman, because he was the incumbent president at the time it was proposed by Congress. Truman, who had served nearly all of Franklin D. Roosevelt's unexpired fourth term and who was elected to a full term in 1948, was thus eligible to seek re-election in 1952.[12] However, with his job approval rating floundering at around 27%,[18][19] and after a poor performance in the 1952 New Hampshire primary, Truman chose not to seek his party's nomination. He theoretically also would have been eligible in later elections.

Since coming into force in 1951, the amendment has applied to six presidents who have been elected twice: Dwight D. Eisenhower, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama.

It could have impacted two who entered office intra-term due to their predecessor's death or resignation: Lyndon B. Johnson and Gerald Ford.[1] Johnson became president in November 1963, following the assassination of John F. Kennedy, served out the final 1 year and 59 days of Kennedy's term, and was elected to a full four-year term in 1964. Four years later, he briefly ran for a second full term, but withdrew from the race during the party primaries.[20][21] Had Johnson served a second full term – through January 20, 1973 – the total length of his presidency would have been 9 years and 59 days; as it happened, Johnson died two days after this date.[22] Gerald Ford, who became president in August 1974 following the resignation of Richard Nixon, served the final 2 years and 164 days of Nixon's term, and attempted to win a full four-year term in 1976, but was defeated by Jimmy Carter. Johnson was eligible to be elected to two full terms in his own right, as he had served less than two years of Kennedy's unexpired term, whereas Ford was eligible to be elected to only one full term, as he had served more than two years of Nixon's unexpired term.[1]

Interaction with the Twelfth Amendment

As worded, the primary focus of the 22nd Amendment is on limiting individuals twice elected to the presidency from being elected again. Due to this, several issues could be raised regarding the amendment's meaning and application, especially in relation to the 12th Amendment, ratified in 1804, which states, "But no person constitutionally ineligible to the office of President shall be eligible to that of Vice-President of the United States".[23] While it is clear that under the 12th Amendment the original constitutional qualifications of age, citizenship, and residency apply to both the president and vice president, it is unclear whether someone who is ineligible to be elected president could be elected vice president. Because of this apparent ambiguity, there may be a loophole in the 22nd Amendment whereby a two-term former president could be elected vice president and then succeed to the presidency as a result of the incumbent's death, resignation, or removal from office (or even succeed to the presidency from some other stated office in the presidential line of succession).[8][24]

Some argue that the 22nd Amendment and 12th Amendment bar any two-term president from later serving as vice president as well as from succeeding to the presidency from any point in the presidential line of succession.[25] Others contend that the original intent of the 12th Amendment concerns qualification for service (age, residence, and citizenship), while the 22nd Amendment, concerns qualifications for election, and thus (strictly applying the text) a former two-term president is still eligible to serve as vice president (neither amendment restricts the number of times an individual can be elected to the vice presidency), and then succeed to the presidency to serve out the balance of the term (though prohibited from running for election to an additional term).[26][27]

The practical applicability of this distinction has not been tested, as no former president has ever sought the vice presidency. In 1980, former president Gerald Ford was mentioned as a possible vice presidential running mate for Republican presidential nominee Ronald Reagan, and there were some negotiations between the two camps, but nothing ever came of the idea.[28] During Hillary Clinton's 2016 presidential campaign, she jokingly said that she had considered naming her husband Bill Clinton as her vice presidential running mate, but had been advised it would be unconstitutional.[29] Most likely, the constitutional question raised will remain unanswered unless the situation actually occurs.[1]

Attempts at repeal

Over the years, several presidents have voiced their antipathy toward the amendment. After leaving office, Harry Truman variously described it as: "bad", "stupid", and "one of the worst that has been put into the Constitution, except for the Prohibition Amendment".[30] In January 1989, during an interview with Tom Brokaw a few days prior to leaving office, Ronald Reagan stated his intention to push for a repeal of the 22nd Amendment, calling it "an infringement on the democratic rights of the people".[31] In a November 2000 interview with Rolling Stone, out-going President Bill Clinton suggested that, given longer life expectancy, perhaps the 22nd Amendment should be altered so as to limit presidents to two consecutive terms.[32] On multiple occasions since taking office in 2017, President Donald Trump has questioned presidential term limits and in public remarks has talked about serving beyond the limits of the 22nd Amendment. For instance, during an April 2019 White House event for the Wounded Warrior Project, he joked that he would remain president "at least for 10 or 14 years".[33][34]

The first efforts in Congress to repeal the 22nd Amendment were undertaken in 1956, only five years after the amendment's ratification. According to the Congressional Research Service, over the ensuing half-century (through 2008) 54 joint resolutions seeking to repeal the two-term presidential election limit were introduced (primarily in the House); none were given serious consideration.[1] Between 1997 and 2013, José E. Serrano, Democratic representative for New York, introduced nine resolutions (one per Congress, all unsuccessful) to repeal the amendment.[35] Repeal has also been supported by senior congressmen such as Barney Frank and David Dreier and Senators Mitch McConnell[36] and Harry Reid.[37]

See also

- Term limits in the United States

- List of political term limits

References

- Neale, Thomas H. (October 19, 2009). "Presidential Terms and Tenure: Perspectives and Proposals for Change" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, The Library of Congress. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- "Constitution of the United States of America: Analysis and Interpretation" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. August 26, 2017. pp. 39–40. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- Buckley, F. H.; Metzger, Gillian. "Twenty-second Amendment". The Interactive Constitution. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The National Constitution Center. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- First draft U.S.CONST., art. X, section 1.

- Ferling, John (2009). The Ascent of George Washington: The Hidden Political Genius of an American Icon. New York: Bloomsbury Press. pp. 347–348. ISBN 978-1-59691-465-0.

- Jefferson, Thomas (December 10, 1807). "Letter to the Legislature of Vermont". Ashland, Ohio: TeachingAmericanHistory.org. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- Peabody, Bruce. "Presidential Term Limit". The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- Peabody, Bruce G.; Gant, Scott E. (February 1999). "The Twice and Future President: Constitutional Interstices and the Twenty-Second Amendment". Minnesota Law Review. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Law School. 83 (3): 565–635. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- Pietrusza, David (2007). The Year of the Six Presidents. New York: Carroll and Graf. pp. 187–200. ISBN 978-0-78671-622-7.

- Saunders, Robert M. (1998). In Search of Woodrow Wilson: Beliefs and Behavior. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 260–262. ISBN 9780313305207.

- Rosen, Elliot A. (1997). "'Not Worth a Pitcher of Warm Piss': John Nance Garner as Vice President". In Walch, Timothy (ed.). At the President's Side: The Vice Presidency in the Twentieth Century. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0-8262-1133-X. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- "FDR's third-term decision and the 22nd amendment". Constitution Daily. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The National Constitution Center. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- Jordan, David M. (2011). FDR, Dewey, and the Election of 1944. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-253-35683-3.

- Leuchtenburg, William E. "Franklin D. Roosevelt: Campaigns and Elections". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- Leuchtenburg, William E. "Franklin D. Roosevelt: Death of the President". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- Rowley, Sean (July 26, 2014). "Presidential terms limited by 22nd Amendment". Tahlequah Daily Press. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- Mount, Steve (January 2007). "Ratification of Constitutional Amendments". Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- Weldon, Kathleen (August 11, 2015). "The Public and the 22nd Amendment: Third Terms and Lame Ducks". Huffington Post. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- Peters, Gerhard; Woolley, John T. "Presidential Job Approval: F. Roosevelt (1941) – Trump". Data adapted from the Gallup Poll and compiled by Gerhard Peters. Santa Barbara, California: The American Presidency Project. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- "Historically, odds were stacked against any President seeking a third term". Constitution Daily. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The National Constitution Center. December 27, 2016. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- Wicker, Tom (April 1, 1968). "Johnson Says He Won't Run · Surprise Decision: President Steps Aside in Unity Bid—Says 'House' Is Divided". The New York Times. Retrieved March 22, 2018 – via The Learning Network.

- Freidel, Frank; Sidey, Hugh (2006). "Lyndon B. Johnson Biography". The White House. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- "The Constitution: Amendments 11-27". America's Founding Documents. Washington, D.C.: National Archives. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- Ready, Joel A. "The 22nd Amendment Doesn't Say What You Think It Says". Blandon, Pennsylvania: Cornerstone Law Firm. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- Franck, Matthew J. (July 31, 2007). "Constitutional Sleight of Hand". National Review. Archived from the original on June 13, 2008. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- Dorf, Michael C. (August 2, 2000). "Why the Constitution permits a Gore-Clinton ticket". CNN. Archived from the original on October 1, 2005.

- Gant, Scott E.; Peabody, Bruce G. (June 13, 2006). "How to bring back Bill: A Clinton-Clinton 2008 ticket is constitutionally possible". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- Burr, Richard (April 7, 2017). "1980 convention launched 'Reagan Revolution'". The Detroit News. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

- LoBianco, Tom (September 15, 2015). "Hillary Clinton: Bill as VP has 'crossed her mind'". CNN. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- Lemelin, Bernard Lemelin (Winter 1999). "Opposition to the 22nd Amendment: The National Committee Against Limiting the Presidency and its Activities, 1949-1951". Canadian Review of American Studies. University of Toronto Press on behalf of the Canadian Association for American Studies with the support of Carleton University. 29 (3): 133–148. doi:10.3138/CRAS-029-03-06.

- Reagan, Ronald (January 18, 1989). "President Reagan Says He Will Fight to Repeal 22nd Amendment". NBC Nightly News (Interview). Interviewed by Tom Brokaw. New York: NBC. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- "Clinton: I Would've Won Third Term". ABC News. December 7, 2000. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- Einbinder, Nicole (June 17, 2019). "Trump suggested his supporters want him to serve more than 2 terms as president". Business Insider. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- Croucher, Shane (September 11, 2019). "Donald Trump Posts Image on Twitter, Instagram Joking That He'll Stand in 2024". Newsweek. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- "H.J.Res. 15 (113th): Proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States to repeal the twenty-second article of amendment, thereby removing the limitation on the number of terms an individual may serve as President". Washington, D.C.: GovTrack, a project of Civic Impulse, LLC. 2013. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- "FACT CHECK: Bill to Repeal the 22nd Amendment".

- potus_geeks (February 27, 2012). "The 22nd Amendment".