Impeachment in the United States

Impeachment in the United States is the process by which a legislature (usually in the form of the lower house) brings charges against a civil officer of government for crimes alleged to have been committed, analogous to the bringing of an indictment by a grand jury. Impeachment may occur at the federal level or the state level. The federal House of Representatives can impeach federal officials, including the president, and each state's legislature can impeach state officials, including the governor, in accordance with their respective federal or state constitution.

Most impeachments have concerned alleged crimes committed while in office, though there have been a few cases in which officials have been impeached and subsequently convicted for crimes committed prior to taking office.[1] The impeached official remains in office until a trial is held. That trial, and removal from office if convicted, is separate from the act of impeachment itself.

In impeachment proceedings, the defendant does not risk forfeiture of life, liberty, or property. According to the Constitution, the only penalties allowed to be imposed by the Senate are removal from office and disqualification from holding any federal office in the future.

Federal impeachment

Constitutional provisions

There are several provisions in the United States Constitution relating to impeachment:

Article I, Section 2, Clause 5 provides:

The House of Representatives shall choose their Speaker and other Officers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment.

Article I, Section 3, Clauses 6 and 7 provide:

The Senate shall have the sole Power to try all Impeachments. When sitting for that Purpose, they shall be on Oath or Affirmation. When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside: And no Person shall be convicted without the Concurrence of two-thirds of the Members present. Judgment in Cases of Impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States; but the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law.

Article II, Section 2 provides:

[The President] ... shall have power to grant reprieves and pardons for offenses against the United States, except in cases of impeachment.

Article II, Section 4 provides:

The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.[2]

Impeachable offenses: "Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors"

The Constitution limits grounds of impeachment to "Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors".[3] The precise meaning of the phrase "high Crimes and Misdemeanors" is not defined in the Constitution itself.

"High crimes and misdemeanors", in the legal and common parlance of England in the 17th and 18th centuries, is corrupt activity by those who have special duties that are not shared with common persons.[4] Toward the end of the 1700s, "High crimes and misdemeanors" acquired a more technical meaning. As Blackstone says in his Commentaries: The first and principal high misdemeanor...was mal-administration of such high offices as are in public trust and employment.[5]

The notion that only criminal conduct can constitute sufficient grounds for impeachment does not comport with either the views of the founders or with historical practice.[1] Alexander Hamilton, in Federalist 65, described impeachable offenses as arising from "the misconduct of public men, or in other words from the abuse or violation of some public trust".[6] Such offenses were "political, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself".[6] According to this reasoning, impeachable conduct could include behavior that violates an official's duty to the country, even if such conduct is not necessarily a prosecutable offense. Indeed, in the past both houses of Congress have given the phrase "high Crimes and Misdemeanors" a broad reading, finding that impeachable offenses need not be limited to criminal conduct.[1][7]

The purposes underlying the impeachment process also indicate that non-criminal activity may constitute sufficient grounds for impeachment.[1][8] The purpose of impeachment is not to inflict personal punishment for criminal activity. Instead, impeachment is a "remedial" tool; it serves to effectively "maintain constitutional government" by removing individuals unfit for office.[1][9] Grounds for impeachment include abuse of the particular powers of government office or a violation of the "public trust"—conduct that is unlikely to be barred via statute.[1][7][9]

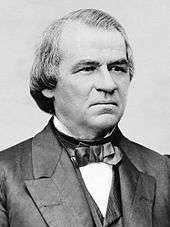

In drawing up articles of impeachment, the House has placed little emphasis on criminal conduct.[1] Less than one-third of the articles that the House have adopted have explicitly charged the violation of a criminal statute or used the word "criminal" or "crime" to describe the conduct alleged.[1] Officials have been impeached and removed for drunkenness, biased decision-making, or inducing parties to enter financial transactions, none of which is specifically criminal.[1] Two of the articles against President Andrew Johnson were based on rude speech that reflected badly on the office: President Johnson had made "harangues" criticizing the Congress and questioning its legislative authority, refusing to follow laws, and diverting funds allocated in an army appropriations act, each of which brought the presidency "into contempt, ridicule, and disgrace".[10] A number of individuals have been impeached for behavior incompatible with the nature of the office they hold.[1] Some impeachments have addressed, at least in part, conduct before the individuals assumed their positions: for example, Article IV against Judge Thomas Porteous related to false statements to the FBI and Senate in connection with his nomination and confirmation to the court.[1]

On the other hand, the Constitutional Convention rejected language that would have permitted impeachment for "maladministration", with Madison arguing that "[s]o vague a term will be equivalent to a tenure during pleasure of the Senate."[11]

Congressional materials have cautioned that the grounds for impeachment "do not all fit neatly and logically into categories" because the remedy of impeachment is intended to "reach a broad variety of conduct by officers that is both serious and incompatible with the duties of the office".[1][9] Congress has identified three general types of conduct that constitute grounds for impeachment, although these categories should not be understood as exhaustive:

- improperly exceeding or abusing the powers of the office;

- behavior incompatible with the function and purpose of the office; and

- misusing the office for an improper purpose or for personal gain.[1][9]

Conversely, not all criminal conduct is impeachable: in 1974, the Judiciary Committee rejected an article of impeachment against President Nixon alleging that he committed tax fraud, primarily because that "related to the President's private conduct, not to an abuse of his authority as President".[1]

Several commentators have suggested that Congress alone may decide for itself what constitutes a "high Crime or Misdemeanor", especially since the Supreme Court decided in Nixon v. United States that it did not have the authority to determine whether the Senate properly "tried" a defendant.[12] In 1970, then-House Minority Leader Gerald R. Ford defined the criterion as he saw it: "An impeachable offense is whatever a majority of the House of Representatives considers it to be at a given moment in history."[13]

Of the 20 impeachments voted by the House:

- No official has been charged with treason. (In 1797, Senator Blount was impeached for assisting Britain in capturing Spanish territory. In 1862, Judge Humphries was impeached and convicted for siding with the Confederacy and taking a position as a Confederate judge during the Civil War.)

- Three officials have been charged with bribery. Of those, two proceeded to trial and were removed (Judge Archibald and Judge Hastings); the other resigned prior to trial (Secretary Belknap).

- The remaining charges against all the other officials fall under the category of "high Crimes and Misdemeanors".

The standard of proof required for impeachment and conviction is also left to the discretion of individual Representatives and Senators, respectively. Defendants have argued that impeachment trials are in the nature of criminal proceedings, with convictions carrying grave consequences for the accused, and that therefore proof beyond a reasonable doubt should be the applicable standard. House Managers have argued that a lower standard would be appropriate to better serve the purpose of defending the community against abuse of power, since the defendant does not risk forfeiture of life, liberty, or property, for which the reasonable doubt standard was set.[14]

Officers subject to impeachment: "civil officers of the United States"

The Constitution gives Congress the authority to impeach and remove "The President, Vice President, and all civil officers of the United States" upon a determination that such officers have engaged in treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors. The Constitution does not articulate who qualifies as a "civil officer of the United States".[15]

Federal judges are subject to impeachment. In fact, 15 of 20 officers impeached, and all eight officers removed after Senate trial, have been judges. The most recent impeachment effort against a Supreme Court justice that resulted in a House of Representatives investigation was against Justice William O. Douglas. In 1970, Representative Gerald Ford, who was then House minority leader, called for the House to impeach Douglas. However, a House investigation led by Congressman Emanuel Celler (D-NY) determined that Ford's allegations were baseless. According to Professor Joshua E. Kastenberg at the University of New Mexico, School of Law, Ford and Nixon sought to force Douglas off the Court in order to cement the "Southern Strategy" as well as to provide cover for the invasion of Cambodia. When their efforts failed, Douglas remained on the Court.[16]

Within the executive branch, any Presidentially appointed "principal officer", including a head of an agency such as a Secretary, Administrator, or Commissioner, is a "civil officer of the United States" subject to impeachment.[1] At the opposite end of the spectrum, lesser functionaries, such as federal civil service employees, do not exercise "significant authority", and are not appointed by the President or an agency head. These employees do not appear to be subject to impeachment, though that may be a matter of allocation of House floor debate time by the Speaker, rather than a matter of law.

The Senate has concluded that members of Congress (Representatives and Senators) are not "civil officers" for purposes of impeachment.[17] As a practical matter, expulsion is effected by the simpler procedures of Article I, Section 5, which provides "Each House shall be the Judge of the Elections, Returns and Qualifications of its own Members ... Each House may determine the Rules of its Proceedings, punish its Members for disorderly Behaviour, and, with the Concurrence of two thirds, expel a Member." (see List of United States senators expelled or censured and List of United States Representatives expelled, censured, or reprimanded). This allows each House to expel its own members without involving the other chamber. In 1797, the House of Representatives impeached Senator William Blount of Tennessee.[18] The Senate expelled Senator Blount under Article I, Section 5, on the same day. However, the impeachment proceeding remained pending (expulsion only removes the individual from office, but conviction after impeachment may also bar the individual from holding future office, so the question of further punishment remained to be decided). After four days of debate, the Senate concluded that a Senator is not a "civil officer of the United States" for purposes of the Impeachment clause, and dismissed for lack of jurisdiction.[17][19] The House has not impeached a Member of Congress since Blount.

Procedure

At the federal level, the impeachment process is a three-step procedure.[20]

- First, the Congress investigates. This investigation typically begins in the House Judiciary Committee, but may begin elsewhere. For example, the Nixon impeachment inquiry began in the Senate Judiciary Committee. The facts that led to impeachment of Bill Clinton were first discovered in the course of an investigation by Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr.

- Second, the House of Representatives must pass, by a simple majority of those present and voting, articles of impeachment, which constitute the formal allegation or allegations. Upon passage, the defendant has been "impeached".

- Third, the Senate tries the accused. In the case of the impeachment of a president, the Chief Justice of the United States presides over the proceedings. For the impeachment of any other official, the Constitution is silent on who shall preside, suggesting that this role falls to the Senate's usual presiding officer, the President of the Senate, who is also the Vice President of the United States. Conviction in the Senate requires the concurrence of a two-thirds supermajority of those present. The result of conviction is removal from office.[21]

Rules

A number of rules have been adopted by the House and Senate and are honored by tradition.

Jefferson's Manual, which is integral to the Rules of the House of Representatives,[22] states that impeachment is set in motion by charges made on the floor, charges proffered by a memorial, a member's resolution referred to a committee, a message from the president, or from facts developed and reported by an investigating committee of the House. It further states that a proposition to impeach is a question of high privilege in the House and at once supersedes business otherwise in order under the rules governing the order of business.

The House Practice: A Guide to the Rules, Precedents and Procedures of the House[23] is a reference source for information on the rules and selected precedents governing the House procedure, prepared by the House Parliamentarian. The manual has a chapter on the House's rules, procedures, and precedent for impeachment.

In 1974, as part of the preliminary investigation in the Nixon impeachment inquiry, the staff of the Impeachment Inquiry of the House Judiciary Committee prepared a report, Constitutional Grounds for Presidential Impeachment.[9] The primary focus of the Report is the definition of the term "high Crimes and Misdemeanors" and the relationship to criminality, which the Report traces through history from English roots, through the debates at the 1787 Constitutional Convention, and the history of the impeachments before 1974.

The 1974 report has been expanded and revised on several occasions by the Congressional Research Service, and the current version Impeachment and Removal dates from October 2015.[1] While this document is only staff recommendation, as a practical matter, today it is probably the single most influential definition of "high Crimes and Misdemeanors".

The Senate has formal Rules and Procedures of Practice in the Senate When Sitting on Impeachment Trials.[24]

Calls for impeachment, and Congressional power to investigate

While the actual impeachment of a federal public official is a rare event, demands for impeachment, especially of presidents, are common,[25] going back to the administration of George Washington in the mid-1790s.

While almost all of them were for the most part frivolous and were buried as soon as they were introduced, several did have their intended effect. Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon[26] and Supreme Court Justice Abe Fortas both resigned in response to the threat of impeachment hearings, and most famously, President Richard Nixon resigned from office after the House Judiciary Committee had already reported articles of impeachment to the floor.

In advance of the formal resolution by the full House to authorize proceedings, committee chairmen have the same power for impeachment as for any other issue within the jurisdiction of the committee: to investigate, subpoena witnesses, and prepare a preliminary report of findings. For example:

- In 1970, House minority leader Gerald R. Ford attempted to initiate impeachment proceedings against Associate Justice William O. Douglas; the attempt included a 90-minute speech on the House floor.[27] The House did not vote to initiate proceedings.

- In 1973, the Senate Watergate hearings (with testimony from John Dean, and the revelation of the White House tapes by Alexander Butterfield) were held in May and June 1973, and the House Judiciary Committee authorized Chairman Rodino to commence an investigation, with subpoena power, on October 30, 1973. The full House voted to initiate impeachment proceedings on February 6, 1974, that is, after nine months of formal investigations by various Congressional committees.

- Other examples are discussed in the article on Impeachment investigations of United States federal officials.

Targets of congressional investigations have challenged the power of Congress to investigate before a formal resolution commences impeachment proceedings. For example, President Buchanan wrote to the committee investigating his administration:

I do, therefore, ... solemnly protest against these proceedings of the House of Representatives, because they are in violation of the rights of the coordinate executive branch of the Government, and subversive of its constitutional independence; because they are calculated to foster a band of interested parasites and informers, ever ready, for their own advantage, to swear before ex parte committees to pretended private conversations between the President and themselves, incapable, from their nature, of being disproved; thus furnishing material for harassing him, degrading him in the eyes of the country ...[28]

He maintained that the House of Representatives possessed no general powers to investigate him, except when sitting as an impeaching body.

When the Supreme Court has considered similar issues, it held that the power to secure "needed information ... has long been treated as an attribute of the power to legislate. ... [The power to investigate is deeply rooted in the nation's history:] It was so regarded in the British Parliament and in the colonial Legislatures before the American Revolution, and a like view has prevailed and been carried into effect in both houses of Congress and in most of the state Legislatures."[29] The Supreme Court also held, "There can be no doubt as to the power of Congress, by itself or through its committees, to investigate matters and conditions relating to contemplated legislation."[30]

The Supreme Court considered the power of the Congress to investigate, and to subpoena executive branch officials, in a pair of cases arising out of alleged corruption in the administration of President Warren G. Harding. In the first, McGrain v. Daugherty, the Court considered a subpoena issued to the brother of Attorney General Harry Daugherty for bank records relevant to the Senate's investigation into the Department of Justice. Concluding that the subpoena was valid, the Court explained that Congress's "power of inquiry ... is an essential and appropriate auxiliary to the legislative function", as "[a] legislative body cannot legislate wisely or effectively in the absence of information respecting the conditions which the legislation is intended to affect or change." The Supreme Court held that it was irrelevant that the Senate's authorizing resolution lacked an "avow[al] that legislative action was had in view" because, said the Court, "the subject to be investigated was ... [p]lainly [a] subject ... on which legislation could be had" and such legislation "would be materially aided by the information which the investigation was calculated to elicit." Although "[a]n express avowal" of the Senate's legislative objective "would have been better", the Court admonished that "the presumption should be indulged that [legislation] was the real object."[29]

Two years later, in Sinclair v. United States,[31] the Court considered investigation of private parties involved with officials under potential investigation for public corruption. In Sinclair, Harry Sinclair, the president of an oil company, appealed his conviction for refusing to answer a Senate committee's questions regarding his company's allegedly fraudulent lease on federal oil reserves at Teapot Dome in Wyoming. The Court, acknowledging individuals' "right to be exempt from all unauthorized, arbitrary or unreasonable inquiries and disclosures in respect of their personal and private affairs", nonetheless explained that because "[i]t was a matter of concern to the United States, ... the transaction purporting to lease to [Sinclair's company] the lands within the reserve cannot be said to be merely or principally ... personal." The Court also dismissed the suggestion that the Senate was impermissibly conducting a criminal investigation. "It may be conceded that Congress is without authority to compel disclosures for the purpose of aiding the prosecution of pending suits," explained the Court, "but the authority of that body, directly or through its committees, to require pertinent disclosures in aid of its own constitutional power is not abridged because the information sought to be elicited may also be of use in such suits."

The Supreme Court reached similar conclusions in a number of other cases. In Barenblatt v. United States,[32] the Court permitted Congress to punish contempt, when a person refused to answer questions while testifying under subpoena by the House Committee on Un-American Activities. The Court explained that although "Congress may not constitutionally require an individual to disclose his ... private affairs except in relation to ... a valid legislative purpose", such a purpose was present. Congress's "wide power to legislate in the field of Communist activity ... and to conduct appropriate investigations in aid thereof[] is hardly debatable," said the Court, and "[s]o long as Congress acts in pursuance of its constitutional power, the Judiciary lacks authority to intervene on the basis of the motives which spurred the exercise of that power."

Presidents have often been the subjects of Congress's legislative investigations. For example, in 1832, the House vested a select committee with subpoena power "to inquire whether an attempt was made by the late Secretary of War ... [to] fraudulently [award] ... a contract for supplying rations" to Native Americans and to "further ... inquire whether the President ... had any knowledge of such attempted fraud, and whether he disapproved or approved of the same." In the 1990s, first the House and Senate Banking Committees and then a Senate special committee investigated President and Mrs. Clinton's involvement in the Whitewater land deal and related matters. The Senate had an enabling resolution; the House did not.

The Supreme Court has also explained that Congress has not only the power, but the duty, to investigate so it can inform the public of the operations of government:

It is the proper duty of a representative body to look diligently into every affair of government and to talk much about what it sees. It is meant to be the eyes and the voice, and to embody the wisdom and will of its constituents. Unless Congress have and use every means of acquainting itself with the acts and the disposition of the administrative agents of the government, the country must be helpless to learn how it is being served; and unless Congress both scrutinize these things and sift them by every form of discussion, the country must remain in embarrassing, crippling ignorance of the very affairs which it is most important that it should understand and direct. The informing function of Congress should be preferred even to its legislative function.[33]

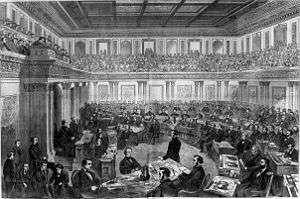

House of Representatives: Impeachment

Impeachment proceedings may be requested by a member of the House of Representatives on his or her own initiative, either by presenting a list of the charges under oath or by asking for referral to the appropriate committee. The impeachment process may be requested by non-members. For example, when the Judicial Conference of the United States suggests a federal judge be impeached, a charge of actions constituting grounds for impeachment may come from a special prosecutor, the President, or state or territorial legislature, grand jury, or by petition. An impeachment proceeding formally begins with a resolution adopted by the full House of Representatives, which typically includes a referral to a House committee.[20]

The type of impeachment resolution determines the committee to which it is referred. A resolution impeaching a particular individual is typically referred to the House Committee on the Judiciary. A resolution to authorize an investigation regarding impeachable conduct is referred to the House Committee on Rules, and then to the Judiciary Committee. The House Committee on the Judiciary, by majority vote, will determine whether grounds for impeachment exist (this vote is not law and is not required, US Constitution and US law).

Articles of impeachment

Where the Committee finds grounds for impeachment, it will set forth specific allegations of misconduct in one or more articles of impeachment. The Impeachment Resolution, or Articles of Impeachment, are then reported to the full House with the committee's recommendations.

The House debates the resolution and may at the conclusion consider the resolution as a whole or vote on each article of impeachment individually. A simple majority of those present and voting is required for each article for the resolution as a whole to pass. If the House votes to impeach, managers (typically referred to as "House managers", with a "lead House manager") are selected to present the case to the Senate. Recently, managers have been selected by resolution, while historically the House would occasionally elect the managers or pass a resolution allowing the appointment of managers at the discretion of the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives. These managers are roughly the equivalent of the prosecution or district attorney in a standard criminal trial. Also, the House will adopt a resolution in order to notify the Senate of its action. After receiving the notice, the Senate will adopt an order notifying the House that it is ready to receive the managers. The House managers then appear before the bar of the Senate and exhibit the articles of impeachment. After the reading of the charges, the managers return and make a verbal report to the House.

Senate trial

The proceedings unfold in the form of a trial, with the Senate having the right to call witnesses and each side having the right to perform cross-examinations.[24] The House members, who are given the collective title of managers during the course of the trial, present the prosecution case, and the impeached official has the right to mount a defense with his or her own attorneys as well. Senators must also take an oath or affirmation that they will perform their duties honestly and with due diligence. After hearing the charges, the Senate usually deliberates in private. The Constitution requires a two-thirds supermajority to convict a person being impeached.[34] The Senate enters judgment on its decision, whether that be to convict or acquit, and a copy of the judgment is filed with the Secretary of State.[24] Upon conviction in the Senate, the official is automatically removed from office and may also be barred from holding future office. The trial is not an actual criminal proceeding and more closely resembles a civil service termination appeal in terms of the contemplated deprivation. Therefore, the removed official may still be liable to criminal prosecution under a subsequent criminal proceeding. The President may not grant a pardon in the impeachment case, but may in any resulting Federal criminal case.[35]

Beginning in the 1980s with Harry E. Claiborne, the Senate began using "Impeachment Trial Committees" pursuant to Senate Rule XI.[24] These committees presided over the evidentiary phase of the trials, hearing the evidence and supervising the examination and cross-examination of witnesses. The committees would then compile the evidentiary record and present it to the Senate; all senators would then have the opportunity to review the evidence before the chamber voted to convict or acquit. The purpose of the committees was to streamline impeachment trials, which otherwise would have taken up a great deal of the chamber's time. Defendants challenged the use of these committees, claiming them to be a violation of their fair trial rights as this did not meet the constitutional requirement for their cases to be "tried by the Senate". Several impeached judges, including District Court Judge Walter Nixon, sought court intervention in their impeachment proceedings on these grounds. In Nixon v. United States (1993),[12] the Supreme Court determined that the federal judiciary could not review such proceedings, as matters related to impeachment trials are political questions and could not be resolved in the courts.[36]

In theory at least, as President of the Senate, the Vice President of the United States could preside over his own impeachment, although legal theories suggest that allowing a defendant to be the judge in his own case would be a blatant conflict of interest. If the Vice President did not preside over an impeachment (of anyone besides the President), the duties would fall to the President pro tempore of the Senate.

To convict an accused, "the concurrence of two thirds of the [Senators] present" for at least one article is required. If there is no single charge commanding a "guilty" vote from two-thirds of the senators present, the defendant is acquitted and no punishment is imposed.

Result of conviction: removal, and with an additional Senate vote, disqualification

Conviction immediately removes the defendant from office. Following conviction, the Senate may vote to further punish the individual by barring him or her from holding future federal office, elected or appointed. As the threshold for disqualification is not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution, the Senate has taken the position that disqualification votes only require a simple majority rather than a two-thirds supermajority. The Senate has used disqualification sparingly, as only three individuals have been disqualified from holding future office.[37]

Conviction does not extend to further punishment, for example, loss of pension. After conviction by the Senate, "the Party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law" in the regular federal or state courts.

History of federal constitutional impeachment

In the United Kingdom, impeachment was a procedure whereby a member of the House of Commons could accuse someone of a crime. If the Commons voted for the impeachment, a trial would then be held in the House of Lords. Unlike a bill of attainder, a law declaring a person guilty of a crime, impeachments did not require royal assent, so they could be used to remove troublesome officers of the Crown even if the monarch was trying to protect them.

The monarch, however, was above the law and could not be impeached, or indeed judged guilty of any crime. When King Charles I was tried before the Rump Parliament of the New Model Army in 1649 he denied that they had any right to legally indict him, their king, whose power was given by God and the laws of the country, saying: "no earthly power can justly call me (who is your King) in question as a delinquent ... no learned lawyer will affirm that an impeachment can lie against the King." While the House of Commons pronounced him guilty and ordered his execution anyway, the jurisdictional issue tainted the proceedings.

With this example in mind, the delegates to the 1787 Constitutional Convention chose to include an impeachment procedure in Article II, Section 4 of the Constitution which could be applied to any government official; they explicitly mentioned the President to ensure there would be no ambiguity. Opinions differed, however, as to the reasons Congress should be able to initiate an impeachment. Initial drafts listed only treason and bribery, but George Mason favored impeachment for "maladministration" (incompetence). James Madison argued that impeachment should only be for criminal behavior, arguing that a maladministration standard would effectively mean that the President would serve at the pleasure of the Senate.[38] Thus the delegates adopted a compromise version allowing impeachment by the House for "treason, bribery and other high crimes and misdemeanors" and conviction by the Senate only with the concurrence of two-thirds of the senators present.

Formal federal impeachment investigations and results

The House of Representatives has initiated impeachment proceedings 62 times since 1789.

The House has impeached 20 federal officers. Of these:

- 15 were federal judges: thirteen district court judges, one court of appeals judge (who also sat on the Commerce Court), and one Supreme Court Associate Justice.

- three were Presidents: Andrew Johnson, Bill Clinton and Donald Trump[39] were later acquitted by the Senate[40]

- one was a Cabinet secretary

- one was a U.S. Senator.

Of the 20 impeachments by the House, two cases did not come to trial because the individuals had left office, seven were acquitted, and eight officials were convicted, all of whom were judges.[41][42] One, former judge Alcee Hastings, was elected as a member of the United States House of Representatives after being removed from office.

Additionally, an impeachment process against Richard Nixon was commenced, but not completed, as he resigned from office before the full House voted on the articles of impeachment.[36] To date, no president or vice president has been removed from office by impeachment and conviction.

The following table lists federal officials for whom impeachment proceedings were instituted and referred to a committee of the House of Representatives. Numbered lines of the table reflect officials impeached by a majority vote of the House. Unnumbered lines are those officials for whom an impeachment proceeding was formally instituted, but ended when (a) the Committee did not vote to recommend impeachment, (b) the Committee recommended impeachment but the vote in the full House failed, or (c) the official resigned or died before the full House vote.

| # | Date of impeachment or investigation | Accused | Office | Accusations | Result[Note 1] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | July 7, 1797 |  |

William Blount | United States Senator (Tennessee) | Conspiring to assist Britain in capturing Spanish territory | Senate refused to accept impeachment of a Senator by the House of Representatives, instead expelling him from the Senate on their own authority[43][Note 2][44] |

| 2 | March 2, 1803 | John Pickering | Judge (District of New Hampshire) | Drunkenness and unlawful rulings | Convicted; removed on March 12, 1804[43][45][44][45] | |

| 3 | March 12, 1804 | .jpg) |

Samuel Chase | Associate Justice (Supreme Court of the United States) | Political bias and arbitrary rulings, promoting a partisan political agenda on the bench[46] | Acquitted on March 1, 1805[43][45] |

| 4 | April 24, 1830 |  |

James H. Peck | Judge (District of Missouri) | Abuse of power[47] | Acquitted on January 31, 1831[43][45][44][45] |

| March to June 1860 |  |

James Buchanan | President of the United States | Corruption | The Covode committee was established March 5, 1860, and submitted its final report on June 16, 1860. The committee found that Buchanan had not done anything to warrant impeachment, but that his was the most corrupt administration since the adoption of the US Constitution in 1789.[48][49] | |

| 5 | May 6, 1862 |  |

West Hughes Humphreys | Judge (Eastern, Middle, and Western Districts of Tennessee) | Supporting the Confederacy | Convicted; removed and disqualified on June 26, 1862[44][43][45][44][45] |

| 6 | February 24, 1868 |  |

Andrew Johnson | President of the United States | Violating the Tenure of Office Act. The Supreme Court would later state in dicta that the (by then repealed) Tenure of Office Act had been unconstitutional.[50] | Acquitted on May 26, 1868, 35–19 in favor of conviction, falling one vote short of two-thirds.[43][44] |

| 7 | February 28, 1873 |  |

Mark W. Delahay | Judge (District of Kansas) | Drunkenness | Resigned on December 12, 1873[45][51][45][51] |

| 8 | March 2, 1876 |  |

William W. Belknap | United States Secretary of War (resigned after impeachment and before trial) | Graft, corruption | Acquitted after his resignation on August 1, 1876[43][44] |

| 9 | December 13, 1904 | Charles Swayne | Judge (Northern District of Florida) | Failure to live in his district, abuse of power[52] | Acquitted on February 27, 1905[43][45][44][45] | |

| 10 | July 11, 1912 | .jpg) |

Robert Wodrow Archbald | Associate Justice (United States Commerce Court) Judge (Third Circuit Court of Appeals) |

Improper acceptance of gifts from litigants and attorneys | Convicted; removed and disqualified on January 13, 1913[44][43][45][44][45] |

| 11 | April 1, 1926 |  |

George W. English | Judge (Eastern District of Illinois) | Abuse of power | Resigned on November 4, 1926,[44][43] proceedings dismissed on December 13, 1926[44][45][44][45] |

| 12 | February 24, 1933 | Harold Louderback | Judge (Northern District of California) | Corruption | Acquitted on May 24, 1933[43][45][44][45] | |

| 13 | March 2, 1936 | .jpg) |

Halsted L. Ritter | Judge (Southern District of Florida) | Champerty, corruption, tax evasion, practicing law while a judge | Convicted; removed on April 17, 1936[43][45][44][45] |

| 1953 |  |

William O. Douglas | Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court | Brief stay of execution for Julius and Ethel Rosenberg | Referred to Judiciary Committee (Jun. 18, 1953); committee voted to end the investigation (Jul 7, 1953). | |

| 1970 |  |

William O. Douglas | Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court | Failure to recuse on obscenity cases while at the same time having articles published in Evergreen Review and Avant-Garde magazines; conflict of paid board positions with two non-profits | Referred to a special subcommittee of the House Judiciary Committee (Apr. 21, 1970); subcommittee voted to end the investigation (Dec. 3, 1970). | |

| 1973–1974 |  |

Richard Nixon | President of the United States | Obstruction of justice, Abuse of Power, Contempt of Congress | House Judiciary Committee begins investigating and issuing subpoenas (Oct. 30, 1973); House Judiciary Report on committee investigation (Feb. 1, 1974);[53] House resolution 93-803 authorizes Judiciary Committee investigation (Feb. 6, 1974);[54] House Judiciary Committee votes three articles of impeachment to House floor (July 27–30, 1974);[55] proceedings terminated by resignation of President Nixon (August 8, 1974). | |

| 14 | July 22, 1986 | .jpg) |

Harry E. Claiborne | Judge (District of Nevada) | Tax evasion | Convicted; removed on October 9, 1986[43][45][44][45] |

| 15 | August 3, 1988 |  |

Alcee Hastings | Judge (Southern District of Florida) | Accepting a bribe, and committing perjury during the resulting investigation | Convicted; removed on October 20, 1989[43][45][44][45] |

| 16 | May 10, 1989 | .jpg) |

Walter Nixon | Chief Judge (Southern District of Mississippi) | Perjury | Convicted; removed on November 3, 1989[43][45][Note 3][44][45] |

| 17 | December 19, 1998 |  |

Bill Clinton | President of the United States | Perjury and obstruction of justice[56] | Acquitted on February 12, 1999: 45–55 on perjury and 50–50 on obstruction of justice[43][57] |

| 18 | June 19, 2009 |  |

Samuel B. Kent | Judge (Southern District of Texas) | Sexual assault, and obstruction of justice during the resulting investigation | Resigned on June 30, 2009,[45][58] proceedings dismissed on July 22, 2009[43][45][59][45][60] |

| 19 | March 11, 2010 |  |

Thomas Porteous | Judge (Eastern District of Louisiana) | Making false financial disclosures, corruption. | Convicted; removed and disqualified on December 8, 2010[43][45][61][45][62] |

| 20 | December 18, 2019 |  |

Donald Trump | President of the United States | Abuse of power and obstruction of Congress | Acquitted on February 5, 2020: 48–52 on abuse of power and 47–53 on obstruction of Congress |

Other impeachment attempts

There were unsuccessful attempts to initiate impeachment proceedings against John Tyler (impeachment defeated in the House, 83–127),[63] George W. Bush, and Barack Obama.

One notable impeachment attempt that never reached the point of House resolution was an attempt to impeach Associate Justice William O. Douglas by then-House Minority Leader Gerald R. Ford. The Legislative Reference Service of the Library of Congress prepared a report as part of Ford's vetting for confirmation as Vice President in 1973.[27]

Impeachment in the states

State legislatures can impeach state officials, including governors, in every state except Oregon. The court for the trial of impeachments may differ somewhat from the federal model—in New York, for instance, the Assembly (lower house) impeaches, and the State Senate tries the case, but the members of the seven-judge New York State Court of Appeals (the state's highest, constitutional court) sit with the senators as jurors as well.[64] Impeachment and removal of governors has happened occasionally throughout the history of the United States, usually for corruption charges. A total of at least eleven U.S. state governors have faced an impeachment trial; a twelfth, Governor Lee Cruce of Oklahoma, escaped impeachment conviction by a single vote in 1912. Several others, most recently Missouri's Eric Greitens, have resigned rather than face impeachment, when events seemed to make it inevitable.[65] The most recent impeachment of a state governor occurred on January 14, 2009, when the Illinois House of Representatives voted 117–1 to impeach Rod Blagojevich on corruption charges;[66] he was subsequently removed from office and barred from holding future office by the Illinois Senate on January 29. He was the eighth U.S. state governor to be removed from office.

The procedure for impeachment, or removal, of local officials varies widely. For instance, in New York a mayor is removed directly by the governor "upon being heard" on charges—the law makes no further specification of what charges are necessary or what the governor must find in order to remove a mayor.

In 2018, the entire Supreme Court of Appeals of West Virginia was impeached, something that has been often threatened, but had never happened before.

State and territorial officials impeached

| Date | Accused | Office | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1804 |  |

William W. Irvin | Associate Judge, Fairfield County, Ohio, Court of Common Pleas | Removed |

| 1832 |  |

Theophilus W. Smith | Associate Justice, Illinois Supreme Court | Acquitted[67] |

| February 26, 1862 |  |

Charles L. Robinson | Governor of Kansas | Acquitted[68] |

| John Winter Robinson | Secretary of State of Kansas | Removed on June 12, 1862[69] | ||

| George S. Hillyer | State auditor of Kansas | Removed on June 16, 1862[69] | ||

| 1871 |  |

William Woods Holden | Governor of North Carolina | Removed |

| 1871 |  |

David Butler | Governor of Nebraska | Removed[68] |

| February 1872 |  |

Harrison Reed | Governor of Florida | Acquitted[70] |

| March 1872 | _(14592180978).jpg) |

George G. Barnard | New York Supreme Court (1st District) | Removed |

| 1872 |  |

Henry C. Warmoth | Governor of Louisiana | "Suspended from office", though trial was not held[71] |

| 1876 |  |

Adelbert Ames | Governor of Mississippi | Resigned[68] |

| 1888 |  |

James W. Tate | Kentucky State Treasurer | Removed |

| 1901 | David M. Furches | Chief Justice, North Carolina Supreme Court | Acquitted[72] | |

| Robert M. Douglas | Associate Justice, North Carolina Supreme Court | Acquitted[72] | ||

| August 13, 1913[73] |  |

William Sulzer | Governor of New York | Removed on October 17, 1913[74] |

| July 1917 |  |

James E. Ferguson | Governor of Texas | Removed[75] |

| October 23, 1923 |  |

John C. Walton | Governor of Oklahoma | Removed |

| January 21, 1929 | Henry S. Johnston | Governor of Oklahoma | Removed | |

| April 6, 1929[76] |  |

Huey P. Long | Governor of Louisiana | Acquitted |

| June 13, 1941 | Daniel H. Coakley | Massachusetts Governor's Councilor | Removed on October 2, 1941 | |

| May 1958[77] | Raulston Schoolfield | Judge, Hamilton County, Tennessee Criminal Court | Removed on July 11, 1958[78] | |

| March 14, 1984[79] | Paul L. Douglas | Nebraska Attorney General | Acquitted by the Nebraska Supreme Court on May 4, 1984[80] | |

| February 6, 1988[81] | Evan Mecham | Governor of Arizona | Removed on April 4, 1988[82] | |

| March 30, 1989[83] | A. James Manchin | State treasurer of West Virginia | Resigned on July 9, 1989, before trial started[84] | |

| January 25, 1991[85] | Ward "Butch" Burnette | Kentucky Commissioner of Agriculture | Resigned on February 6, 1991, before trial started[86] | |

| May 24, 1994[87] | Rolf Larsen | Associate Justice, Pennsylvania Supreme Court | Removed on October 4, 1994, and declared ineligible to hold public office in Pennsylvania[88] | |

| October 6, 1994[89] | Judith Moriarty | Secretary of State of Missouri | Removed by the Missouri Supreme Court on December 12, 1994[90] | |

| November 11, 2004[91] | Kathy Augustine | Nevada State Controller | Censured on December 4, 2004, not removed from office[92] | |

| April 11, 2006[93] | David Hergert | Member of the University of Nebraska Board of Regents | Removed by the Nebraska Supreme Court on July 7, 2006[94] | |

| January 8, 2009 (first vote)[95] |

_(cropped).jpg) |

Rod Blagojevich | Governor of Illinois | 95th General Assembly ended |

| January 14, 2009 (second vote)[96] |

Removed on January 29, 2009, and declared ineligible to hold public office in Illinois[97] | |||

| February 11, 2013[98] |  |

Benigno Fitial | Governor of the Northern Mariana Islands | Resigned on February 20, 2013 |

| August 13, 2018[99] | Robin Davis | Associate Justices, Supreme Court of Appeals of West Virginia | Retired on August 13, 2018.[100] Despite her retirement, the West Virginia Senate refused to dismiss the articles of impeachment and scheduled trial for October 29, 2018 although the trial is currently delayed by court order.[101] | |

| Allen Loughry | Resigned on November 12, 2018.[102][103] Possible trial before the West Virginia Senate delayed by court order.[101] | |||

| Beth Walker | Reprimanded and censured on October 2, 2018, not removed from office.[104] | |||

| Margaret Workman | Chief Justice, Supreme Court of Appeals of West Virginia | Trial before the West Virginia Senate delayed by court order after originally being scheduled for October 15, 2018.[105][106] | ||

| July 24, 2019[107] | .jpg) |

Ricardo Rossello | Governor of Puerto Rico | Resigned on July 24, 2019; with effect August 2, 2019, immediately stopping impeachment proceedings |

State governors

At least four state governors have been impeached and removed from office:

- James E. Ferguson, Democratic Governor of Texas, was impeached for misapplication of public funds and embezzlement. In July 1917, Ferguson was convicted and removed from office.

- Jack C. Walton, Democratic Governor of Oklahoma, was impeached for a variety of crimes including illegal collection of campaign funds, padding the public payroll, suspension of habeas corpus, excessive use of the pardon power, and general incompetence. In November 1923, Walton was convicted and removed from office.[108]

- Evan Mecham, Republican Governor of Arizona, was impeached for obstruction of justice and misusing government funds[109] and removed from office in April 1988.

- Rod Blagojevich, Democratic Governor of Illinois, was impeached for abuse of power and corruption, including an attempt to sell the appointment to the United States Senate seat vacated by the resignation of Barack Obama.[110] He was removed from office in January 2009.

See also

- Censure in the United States

- Impeachment attempt against John Tyler

- Impeachment investigation against James Buchanan

- Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

- Harry S. Truman—Truman's firing of Gen. Douglas MacArthur led to introduction of two resolutions of impeachment and hearings in the Senate

- Impeachment process against Richard Nixon

- Impeachment of Bill Clinton

- Efforts to impeach George W. Bush

- Efforts to impeach Barack Obama

- Impeachment of Donald Trump

- Efforts to impeach Donald Trump

- Impeachment investigations of United States federal officials

- Impeachment investigations of United States federal judges

- Jefferson's Manual

- List of federal political scandals in the United States

- Recall election

Notes

- Stephen B. Presser, Essays on Article I: ImpeachmentPresser, Stephen B. "Essays on Article I: Impeachment". The Heritage Guide to the Constitution. Heritage Foundation. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- "Removed and disqualified" indicates that following conviction the Senate voted to disqualify the individual from holding further federal office pursuant to Article I, Section 3 of the United States Constitution, which provides, in pertinent part, that "[j]udgment in cases of impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any office of honor, trust or profit under the United States."

- During the impeachment trial of Senator Blount, it was argued that the House of Representatives did not have the power to impeach members of either House of Congress; though the Senate never explicitly ruled on this argument, the House has never again impeached a member of Congress. The Constitution allows either House to expel one of its members by a two-thirds vote, which the Senate had done to Blount on the same day the House impeached him (but before the Senate heard the case).

- Judge Nixon later challenged the validity of his removal from office on procedural grounds; the challenge was ultimately rejected as nonjusticiable by the Supreme Court in Nixon v. United States.

References

- Attribution

![]()

- Cole, J. P.; Garvey, T. (October 29, 2015). "Report No. R44260, Impeachment and Removal" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. pp. 15–16. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- "The Constitution of the United States: A Transcription". National Archives. November 4, 2015. Archived from the original on January 31, 2017. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- "Article II". LII / Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- Roland, Jon (January 19, 1999). "Meaning of High Crimes and Misdemeanors". Constitution Society. Archived from the original on January 3, 2012. Retrieved February 26, 2012.

- US Judiciary Committee (1974). "Constitutional Grounds for Presidential Impeachment: II. The Historical Origins of Impeachment B. The Intentions of the Framers". Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 11, 2019. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

The 'first and principal' high misdemeanor, according to Blackstone, was 'mal-administration of such high officers, as are in public trust and employment' usually punished by the method of parliamentary impeachment.

- THE FEDERALIST No. 65 (Alexander Hamilton)

- Impeachment of Walter L. Nixon, Jr., H.Rept. 101-36 at 5 (1989).

- Storey, Joseph (1833) Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States §794-803 Archived September 25, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- Staff of the Impeachment Inquiry, Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, Constitutional Grounds for Presidential Impeachment, 93rd Conf. 2nd Sess. (Feb. 1974), 1974 Impeachment Inquiry Report

- See Impeachment of President Andrew Johnson, in Impeachment—Selected Materials, Committee on the Judiciary, 93d Cong., Impeachment—Selected Material 692 (Comm. Print 1973).

- Bowsher v. Synar, 478 U.S. 714, 729-30 (1986).

- Nixon v. United States, 506 U.S. 224 (1993).

- Gerald Ford's Remarks on the Impeachment of Supreme Court Justice William Douglas Archived April 12, 2019, at the Wayback Machine April 15, 1970. Retrieved 21 March 2019.]

- Ripy, Thomas B. "Standard of Proof in Senate Impeachment Proceedings". Congressional Research Service. Archived from the original on April 23, 2019. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- The Constitution also discusses the President's power to appoint "Officers of the United States", "the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments", and "Inferior officers". These are different.

- Joshua E. Kastenberg, The Campaign to Impeach Justice William O. Douglas: Nixon, Vietnam, and the Conservative Attack on Judicial Independence (Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2019)

- Senate Journal, 5th Cong., 3rd Sess., December 17, 1798 to January 10, 1799.

- "U.S. Senate: Impeachment". www.senate.gov. Archived from the original on December 2, 2010.

- Buckner F. Milton (1998). The First Impeachment. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865545977.

- Impeachment and Removal Archived November 15, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Congressional Research Service, October 29, 2015

- "U.S. Senate: Constitution of the United States". U.S. Senate. March 4, 1789. Archived from the original on February 10, 2014.

- "House Rules". Archived from the original on December 12, 2010. Retrieved December 31, 2010.

- Parliamentarian of the House, U.S. House of Representatives, The House Practice: A Guide to the Rules, Precedents and Procedures of the House, at https://www.govinfo.gov/collection/house-practice Archived December 21, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Each Congress adopts its own rules, available at https://rules.house.gov/rules-resources Archived December 23, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- "Rules and Procedures of Practice in the Senate When Sitting on Impeachment Trials" (PDF). Senate Manual Containing the Standing Rules, Orders, Laws and Resolutions Affecting the Business of the United States Senate. United States Senate. August 16, 1986. Section 100–126, 105th Congress, pp. 177–185. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- Clark, Richard C. (July 22, 2008). "McFadden's Attempts to Abolish the Federal Reserve System". Scribd. Archived from the original on March 2, 2010. Retrieved June 20, 2009.

Though a Republican, he moved to impeach President Herbert Hoover in 1932 and introduced a resolution to bring conspiracy charges against the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve.

- "National Affairs: Texan, Texan & Texan". Time. January 25, 1932. Archived from the original on October 27, 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- Legislative Reference Service of the Library of Congress, Role of Vice-President Designate Gerald R. Ford in the Attempt to Impeach Associate Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas Archived February 19, 2019, at the Wayback Machine.

- James Buchanan, The Works of James Buchanan Vol. XII, pp. 225–226 (John Bassett Moore ed., J.B. Lippincott Company) (1911)

- McGrain v. Daugherty, 273 U.S. 135, 161 (1927).

- Quinn v. United States, 349 U.S. 155, 160 (1955).

- Sinclair v. United States, 279 U.S. 263 (1929).

- Barenblatt v. United States 360 U.S. 109, 126 (1959).

- United States v. Rumely, 345 U.S. 41, 43 (1953), quoting Woodrow Wilson, Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics, 303.

- "What would Trump have to do to get impeached?". whatifhq.com. Archived from the original on August 26, 2018. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- Gerhardt, Michael J. "Essays on Article I: Punishment for Impeachment". The Heritage Guide to the Constitution. Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on August 30, 2019. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- Presser, Stephen B. "Essays on Article I: Impeachment". The Heritage Guide to the Constitution. Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on August 30, 2019. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- Foley, Edward B. (September 25, 2019). "Congress Should Remove Trump from Office, But Let Him Run Again in 2020". Politico. Archived from the original on September 28, 2019. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- "Welcome to The American Presidency". Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved April 20, 2007.

- Cai, Weiyi; Lai, K. K. Rebecca; Parlapiano, Alicia; White, Jeremy; Buchanan, Larry (December 18, 2019). "Live House Vote: The Impeachment of Donald J. Trump". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- Erskine, Daniel H. (2008). "The Trial of Queen Caroline and the Impeachment of President Clinton: Law As a Weapon for Political Reform". Washington University Global Studies Law Review. 7 (1). ISSN 1546-6981. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- "U.S. Senate: Impeachment". www.senate.gov. Archived from the original on December 8, 2010. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- "Impeachment History". Infoplease. Archived from the original on June 28, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

- "Chapter 4: Complete List of Senate Impeachment Trials". United States Senate. Archived from the original on December 2, 2010. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- U.S. Joint Committee on Printing (September 2006). "Impeachment Proceedings". Congressional Directory. Retrieved June 19, 2009. (Archived by WebCite)

- "Impeachments of Federal Judges". Federal Judicial Center. Archived from the original on June 22, 2017. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- "1801: Senate Tries Supreme Court Justice". November 25, 2014. Archived from the original on March 8, 2018. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- "PBS NewsHour". Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Baker, Jean H.: James Buchanan; Times Books, 2004

- U.S. House Journal, 36th Congress, 1st session, Page 450 Archived December 28, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- Myers v. United States, 272 U.S. 52 (1926).

- "Judges of the United States Courts – Delahay, Mark W." Federal Judicial Center. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved June 20, 2009.

- "Hinds' Precedents, Volume 3 – Chapter 78 – The Impeachment and Trial of Charles Swayne". Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2013.

- House Rept 93–774

- "Actions - H.Res.803 - 93rd Congress (1973-1974): Resolution providing appropriate power to the Committee on the Judiciary to conduct an investigation of whether sufficient grounds exist to impeach Richard M. Nixon, President of the United States". www.congress.gov. February 6, 1974. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- "Full text of "Watergate Hearings Before the House Committee on the Judiciary"". archive.org.

- https://www.congress.gov/congressional-report/105th-congress/house-report/830 Archived June 25, 2019, at the Wayback Machine House Report 105-830 – Impeachment of William Jefferson Clinton, President of the United States

- Erskine, Daniel H (2008). "The Trial of Queen Caroline and the Impeachment of President Clinton: Law As a Weapon for Political Reform". Washington University Global Studies Law Review. Washington University in St. Louis. 7 (1). Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- Gamboa, Suzanne (June 30, 2009). "White House accepts convicted judge's resignation". Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 26, 2010. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- Gamboa, Suzanne (July 22, 2009). "Congress ends jailed judge's impeachment". Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- Powell, Stewart (June 19, 2009). "U.S. House impeaches Kent". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on June 21, 2009. Retrieved June 19, 2009.

In action so rare it has been carried out only 14 times since 1803, the House on Friday impeached a federal judge—imprisoned U.S. District Court Judge Samuel B. Kent ...

- Alpert, Bruce; Tilove, Jonathan (December 8, 2010). "Senate votes to remove Judge Thomas Porteous from office". New Orleans Times-Picayune. Archived from the original on December 11, 2010. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- Alpert, Bruce (March 11, 2010). "Judge Thomas Porteous impeached by U.S. House of Representatives". New Orleans Times-Picayune. Archived from the original on April 19, 2010. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- Baker, Peter (November 30, 2019). "Long Before Trump, Impeachment Loomed Over Multiple Presidents". New York Times. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- New York State Constitution, Article VI, § 24

- Suntrup, Jack; Erickson, Kurt. "Embattled Gov. Eric Greitens resigns". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Archived from the original on June 2, 2018. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- "House votes to impeach Blagojevich again". Chicago Tribune. January 14, 2009. Archived from the original on January 19, 2009. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- Bateman, Newton; Selby, Paul; Shonkwiler, Frances M.; Fowkes, Henry L. (1908). Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois. Chicago, IL: Munsell Publishing Company. p. 489. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2019.

- "Impeachment of State Officials". Cga.ct.gov. Archived from the original on July 6, 2008. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- Blackmar, Frank (1912). Kansas: A Cyclopedia of State History. Standard Publishing Co. p. 598.

- "Letters Relating to the Efforts to Impeach Governor Harrison Reed During the Reconstruction Era". floridamemory.com. Archived from the original on May 29, 2016. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- "State Governors of Louisiana: Henry Clay Warmoth". Enlou.com. Archived from the original on April 6, 2008. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- News & Observer: NC's dark impeachment history Archived July 21, 2017, at the Wayback Machine by Rob Christensen

- "Sulzer Impeached by Assembly But Refuses to Surrender Office", Syracuse Herald, August 13, 1913, p. 1

- "High Court Removes Sulzer from Office by a Vote of 43 to 12", Syracuse Herald, October 17, 1913, p. 1

- Block, Lourenda (2000). "Permanent University Fund: Investing in the Future of Texas". TxTell (University of Texas at Austin). Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- Official Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Louisiana, April 6, 1929 pp. 292–94

- "Raulston Schoolfield, Impeached Judge, Dies". UPI. October 8, 1982. Archived from the original on February 4, 2016. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- "Impeachment Trial Finds Judge Guilty". AP. July 11, 1958. Archived from the original on October 26, 2016. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- "Attorney General is Impeached". AP. March 14, 1984. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- "Nebraskan Found Not Guilty". AP. May 4, 1984. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- Gruson, Lindsey (February 6, 1988). "House Impeaches Arizona Governor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- Gruson, Lindsey (April 5, 1988). "Arizona's Senate Ousts Governor, Voting Him Guilty of Misconduct". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- AP staff reporter (March 30, 1989). "Impeachment in West Virginia". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- Wallace, Anise C. (July 10, 1989). "Treasurer of West Virginia Retires Over Fund's Losses". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- "Kentucky House Votes To Impeach Jailed Official". Orlando Sentinel. January 26, 1991. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

The House voted unanimously Friday to impeach the agriculture commissioner six days after he began serving a one-year sentence for a payroll violation.

- "Jailed Official Resigns Before Impeachment Trial". Orlando Sentinel. February 7, 1991. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

Kentucky's commissioner of agriculture, serving a one-year jail sentence for felony theft, resigned Wednesday hours before his impeachment trial was scheduled to begin in the state Senate.

- Hinds, Michael deCourcy (May 25, 1994). "Pennsylvania House Votes To Impeach a State Justice". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

A State Supreme Court justice convicted on drug charges was impeached today by the Pennsylvania House of Representatives.

- Moushey, Bill; Tim Reeves (October 5, 1994). "Larsen Removed Senate Convicts Judge On 1 Charge". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh, PA. p. A1. Archived from the original on May 19, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

Rolf Larsen yesterday became the first justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court to be removed from office through impeachment. The state Senate, after six hours of debate, found Larsen guilty of one of seven articles of impeachment at about 8:25 p.m, then unanimously voted to remove him permanently from office and bar him from ever seeking an elected position again.

- Young, Virginia (October 7, 1994). "Moriarty Is Impeached – Secretary Of State Will Fight Removal". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, MO. p. 1A. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

The House voted overwhelmingly Thursday to impeach Secretary of State Judith K. Moriarty for misconduct that 'breached the public trust'. The move, the first impeachment in Missouri in 26 years, came at 4:25 p.m. in a hushed House chamber.

- Young, Virginia; Bell, Kim (December 13, 1994). "High Court Ousts Moriarty". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, MO. p. 1A. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

In a unanimous opinion Monday, the Missouri Supreme Court convicted Secretary of State Judith K. Moriarty of misconduct and removed her from office.

- Vogel, Ed (November 12, 2004). "Augustine impeached". Review-Journal. Archived from the original on November 13, 2004. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- Whaley, Sean (December 5, 2004). "Senate lets controller keep job". Review-Journal. Archived from the original on March 5, 2010. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- Jenkins, Nate (April 11, 2006). "Hergert impeached". Lincoln Journal Star. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

With the last vote and by the slimmest of margins, the Legislature did to University of Nebraska Regent David Hergert Wednesday what it hadn't done in 22 years—move to unseat an elected official.

- "Hergert Convicted". WOWT-TV. August 8, 2006. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

University of Nebraska Regent David Hergert was convicted Friday of manipulating campaign-finance laws during his 2004 campaign and then lying to cover it up. The state Supreme Court ruling immediately removed Hergert, 66, from office.

- Staff reporter (January 9, 2009). "Illinois House impeaches Gov. Rod Blagojevich". AP. Archived from the original on November 6, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- Mckinney, Dave; Wilson, Jordan (January 14, 2009). "Illinois House impeaches Gov. Rod Blagojevich". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- Long, Ray; Rick Pearson (January 30, 2009). "Blagojevich is removed from office". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 1, 2010. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- Eugenio, Haidee V. (January 9, 2009). "CNMI governor impeached on 13 charges". Saipan Tribune. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- "The Latest: All 4 West Virginia justices impeached". AP NEWS. August 14, 2018. Archived from the original on October 6, 2019. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- "WV Supreme Court Justice Robin Davis retires after her impeachment". Herald-Dispatch. Associated Press. August 14, 2018. Archived from the original on August 14, 2018. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- "Effort to remove convicted Justice Loughry from office continues". Archived from the original on October 29, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- "The Latest: W.Va. lawmakers won't meet after justice resigns". Associated Press. November 11, 2018. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- Allen Adams, Steven (November 12, 2018). "Facing Possible Impeachment, West Virginia Supreme Court Justice Resigns". Governing. Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- MetroNews, WSAZ News Staff, WV. "Senators reprimand Justice Walker, but vote to not impeach". www.wsaz.com. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- writer, Phil Kabler Staff. "With Workman impeachment trial blocked, Senate debates next move". Charleston Gazette-Mail. Archived from the original on January 21, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- MORRIS, JEFF (October 11, 2018). "West Virginia Supreme Court halts impeachment trial for Justice Workman". WCHS. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- "Méndez le notificó a Rosselló que el proceso de residenciamiento había iniciado". Archived from the original on October 4, 2019. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- O'Dell, Larry. "WALTON, JOHN CALLOWAY (1881–1949) Archived December 16, 2014, at the Wayback Machine", Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture Archived April 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved July 2, 2013.

- Watkins, Ronald J. (1990). High Crimes and Misdemeanors: The Term and Trials of Former Governor Evan Mecham. New York: William Morrow & Co. ISBN 978-0-688-09051-7.

- Saulny, Susan (January 9, 2009). "Illinois House Impeaches Governor". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 17, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

Further reading

- Berger, Raoul (1999). Impeachment: The Constitutional Problems. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674444782.

- Black, Charles L. (1998). Impeachment: A Handbook. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300079500.

- Lichtman, Allan J. (2017), The Case for Impeachment, Dey Street Books, ISBN 978-0062696823

- Sunstein, Cass R. (2017). Impeachment: A Citizen's Guide. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674983793.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Impeachment in the United States. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- An Overview of the Impeachment Process at congressionalresearch.com

- Congressional Research Service at congressionalresearch.com

- Constitution Annotated - Resources about Impeachment

- House Judiciary Committee, Constitutional Grounds for Presidential Impeachment, February 1974, and Politico story, September 2019

- U.S. Senate : Impeachment