Virginia Plan

The Virginia Plan (also known as the Randolph Plan, after its sponsor, or the Large-State Plan) was a proposal by Virginia delegates during the United States Constitutional Convention for a bicameral legislative branch.[1] The plan was drafted by James Madison while he waited for a quorum to assemble at the Constitutional Convention of 1787.[2][3] The Virginia Plan was notable for its role in setting the overall agenda for debate in the convention and, in particular, for setting forth the idea of population-weighted representation in the proposed national legislature.

| Virginia Plan | |

|---|---|

Front side of the Virginia Plan 1787 | |

| Created | May 29, 1787 |

| Location | National Archives |

| Author(s) | James Madison |

| Purpose | Propose a structure of government to the Philadelphia Convention |

It existed alongside the New Jersey Plan for the structure of the United States government, which was formed in response to the Virginia Plan to protect small states' interests.

Background

The Constitutional Convention gathered in Philadelphia to revise the Articles of Confederation. The Virginia delegation took the initiative to frame the debate by immediately drawing up and presenting a proposal, for which delegate James Madison is given chief credit. However, it was Edmund Randolph, the Virginia governor at the time, who officially put it before the convention on May 29, 1787, in the form of 15 resolutions.[4]

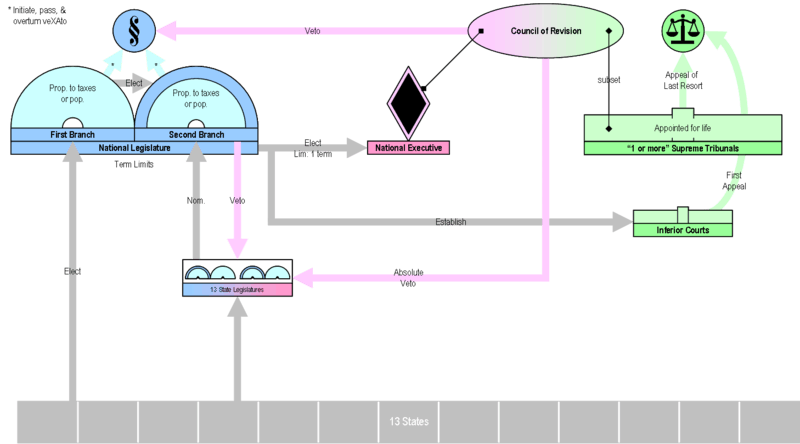

The scope of the resolutions, going well beyond tinkering with the Articles of Confederation, succeeded in broadening the debate to encompass fundamental revisions to the structure and powers of the national government. The resolutions proposed, for example, a new form of national government having three branches (legislative, executive and judicial). One contentious issue facing the convention was the manner in which large and small states would be represented in the legislature: proportionate to population, with larger states having more votes than less-populous states, or by equal representation for each state, regardless of its size and population. The latter system more closely resembled that of the Articles of Confederation, under which each state was represented by one vote in a unicameral legislature.

Principles

The Virginia Plan proposed a legislative branch consisting of two chambers (bicameral legislature), with the dual principles of rotation in office and recall applied to the lower house of the national legislature.[5] Each of the states would be represented in proportion to their "Quotas of contribution, or to the number of free inhabitants."[6] States with a large population, like Virginia (which was the most populous state at the time), would thus have more representatives than smaller states. Large states supported this plan, and smaller states generally opposed it, preferring an alternative put forward on June 15. The New Jersey Plan proposed a single-chamber legislature in which each state, regardless of size, would have one vote, as under the Articles of Confederation. In the end, the convention settled on the Connecticut Compromise, creating a House of Representatives apportioned by population and a Senate in which each state is equally represented.

In addition to dealing with legislative representation, the Virginia Plan addressed other issues as well, with many provisions that did not make it into the Constitution that emerged. It called for a national government of three branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. Members of one of the two legislative chambers would be elected by the people; members of that chamber would then elect the second chamber from nominations submitted by state legislatures. The executive would be chosen by the legislative branch.

Terms of office were not specified, but the executive and members of the popularly elected legislative chamber could not be elected for an undetermined time afterward.

Additionally, the plan proposed that the legislative branch would have the power to veto state laws if they were deemed incompatible with the articles of union,[7][8][9] or the states were deemed incompetent.[10]

The concept of checks and balances was embodied in a provision that legislative acts could be vetoed by a council composed of the executive and selected members of the judicial branch; their veto could be overridden by an unspecified legislative majority.

In popular culture

The Virginia Plan and the debate surrounding it are prominently featured in the 1989 film A More Perfect Union, which depicts the events of the 1787 Constitutional Convention. Presented largely from the viewpoint and words of James Madison, the movie was mainly filmed in Independence Hall.

References

- Frantzich, Stephen E.; Howard R. Ernst (2008). The Political Science Toolbox: A Research Companion to the American Government. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 24. ISBN 0-7425-4762-0.

- Roche, John P. (December 1961). "The Founding Fathers: A Reform Caucus in Action". American Political Science Review. 55.

- Ann Marie Dube (May 1996). "A Multitude of Amendments, Alterations and Additions". National Park Service.

- Virginia Plan of Government, retrieved December 3, 2016

- "Res[olved] that the members of the first branch of the National Legislature ought to be elected by the people of the several States every for the term of;___...to be incapable of reelection for the space of ___after the expiration of their term of service; and to be subject to recall." Max Farrand, ed., The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, 4 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1911), 1:20.

- "Variant Texts of the Virginia Plan, Presented by Edmund Randolph to the Federal Convention, May 29, 1787. Text A", The Avalon Project, Yale Law School, retrieved December 3, 2016

- The Negative on State Laws: James Madison, the Constitution, and the Crisis of Republican Government

- South Carolina v. Katzenbach, Hugo Black, "The proceedings of the original Constitutional Convention show beyond all doubt that the power to veto or negative state laws was denied Congress. On several occasions proposals were submitted to the convention to grant this power to Congress. These proposals were debated extensively and on every occasion when submitted for vote they were overwhelmingly rejected."

- James Madison, the 'Federal Negative,' and the Making of the U.S. Constitution

- Madison Debates July 17

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |