Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux (Latin: Bernardus Claraevallensis; 1090 – 20 August 1153) was a French abbot and a major leader in the revitalization of Benedictine monasticism through the nascent Order of Cistercians.

Saint Bernard of Clairvaux | |

|---|---|

St Bernard in "A Short History of Monks and Monasteries" by Alfred Wesley Wishart (1900) | |

| Abbot Confessor Doctor of the Church Doctor Mellifluus | |

| Born | c. 1090 Fontaine-lès-Dijon, France |

| Died | 20 August 1153 (aged c. 63) Clairvaux, France |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Anglican Communion[1] Lutheranism[2] |

| Canonized | 18 January 1174, Rome by Pope Alexander III |

| Major shrine | Troyes Cathedral Ville-sous-la-Ferté, religious vocations, preachers. |

| Attributes | White Cistercian habit, devil on a chain, white dog |

| Patronage | Cistercians, Burgundy, beekeepers, candlemakers, Gibraltar, Algeciras, Queens' College, Cambridge, Speyer Cathedral, Knights Templar |

| Part of a series on | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Christian mysticism | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Theology · Philosophy

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Practices

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

People (by era or century)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature · Media

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

He was sent to found a new abbey at an isolated clearing in a glen known as the Val d'Absinthe, about 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) southeast of Bar-sur-Aube. According to tradition, Bernard founded the monastery on 25 June 1115, naming it Claire Vallée, which evolved into Clairvaux. There Bernard preached an immediate faith, in which the intercessor was the Virgin Mary.[3] In the year 1128, Bernard attended the Council of Troyes, at which he traced the outlines of the Rule of the Knights Templar,[lower-alpha 1] which soon became the ideal of Christian nobility.

On the death of Pope Honorius II on 13 February 1130, a schism arose in the church. King Louis VI of France convened a national council of the French bishops at Étampes in 1130, and Bernard was chosen to judge between the rivals for pope. By the end of 1131, the kingdoms of France, England, Germany, Portugal, Castile, and Aragon supported Pope Innocent II; however, most of Italy, southern France, and Sicily, with the Latin patriarchs of Constantinople, Antioch, and Jerusalem supported Antipope Anacletus II. Bernard set out to convince these other regions to rally behind Innocent.

In 1139, Bernard assisted at the Second Council of the Lateran. He subsequently denounced the teachings of Peter Abelard to the pope, who called a council at Sens in 1141 to settle the matter. Bernard soon saw one of his disciples elected Pope Eugene III. Having previously helped end the schism within the church, Bernard was now called upon to combat heresy. In June 1145, Bernard traveled in southern France and his preaching there helped strengthen support against heresy. He preached at the Council of Vézelay (1146) to recruit for the Second Crusade.

After the Christian defeat at the Siege of Edessa, the pope commissioned Bernard to preach the Second Crusade. The last years of Bernard's life were saddened by the failure of the crusaders, the entire responsibility for which was thrown upon him. Bernard died at the age of 63, after 40 years as a monk. He was the first Cistercian placed on the calendar of saints, and was canonized by Pope Alexander III on 18 January 1174. In 1830 Pope Pius VIII bestowed upon Bernard the title "Doctor of the Church".

Early life (1090–1113)

Bernard's parents were Tescelin de Fontaine, lord of Fontaine-lès-Dijon, and Alèthe de Montbard, both members of the highest nobility of Burgundy. Bernard was the third of seven children, six of whom were sons. At the age of nine, he was sent to a school at Châtillon-sur-Seine run by the secular canons of Saint-Vorles. Bernard had a great taste for literature and devoted himself for some time to poetry. His success in his studies won the admiration of his teachers. He wanted to excel in literature in order to take up the study of the Bible. He had a special devotion to the Virgin Mary, and he later wrote several works about the Queen of Heaven.[4]

Bernard expanded upon Anselm of Canterbury's role in transmuting the sacramentally ritual Christianity of the Early Middle Ages into a new, more personally held faith, with the life of Christ as a model and a new emphasis on the Virgin Mary. In opposition to the rational approach to divine understanding that the scholastics adopted, Bernard preached an immediate faith, in which the intercessor was the Virgin Mary. He is often cited for saying that Mary Magdalene was the Apostle to the Apostles.

Bernard was only nineteen years of age when his mother died. During his youth, he did not escape trying temptations and around this time he thought of retiring from the world and living a life of solitude and prayer.[5]

In 1098 Robert of Molesme had founded Cîteaux Abbey, near Dijon, with the purpose of restoring the Rule of St Benedict in all its rigour. Returning to Molesme, he left the government of the new abbey to Alberic of Cîteaux, who died in the year 1109. After the death of his mother, Bernard sought admission into the Cistercian order. At the age of 22, while Bernard was at prayer in a church, he felt the calling of God to enter the monastery of Cîteaux.[6] In 1113 Stephen Harding had just succeeded Alberic as third Abbot of Cîteaux when Bernard and thirty other young noblemen of Burgundy sought admission into the monastery.[7] Bernard's testimony was so irresistible that 30 of his friends, brothers, and relatives followed him into the monastic life.[6]

Abbot of Clairvaux (1115–28)

The little community of reformed Benedictines at Cîteaux, which had so profound an influence on Western monasticism, grew rapidly. Three years later, Bernard was sent with a band of twelve monks to found a new house at Vallée d'Absinthe,[6] in the Diocese of Langres. This Bernard named Claire Vallée, or Clairvaux, on 25 June 1115, and the names of Bernard and Clairvaux soon became inseparable.[5] During the absence of the Bishop of Langres, Bernard was blessed as abbot by William of Champeaux, Bishop of Châlons-sur-Marne. From that moment a strong friendship sprang up between the abbot and the bishop, who was professor of theology at Notre Dame of Paris, and the founder of the Abbey of St. Victor, Paris.[4]

The beginnings of Clairvaux Abbey were trying and painful. The regimen was so austere that Bernard became ill, and only the influence of his friend William of Champeaux and the authority of the general chapter could make him mitigate the austerities. The monastery, however, made rapid progress. Disciples flocked to it in great numbers and put themselves under the direction of Bernard. The reputation of his holiness soon attracted 130 new monks, including his own father.[6] His father and all his brothers entered Clairvaux to pursue religious life, leaving only Humbeline, his sister, in the secular world. She, with the consent of her husband, soon took the veil in the Benedictine nunnery of Jully-les-Nonnains. Gerard of Clairvaux, Bernard's older brother, became the cellarer of Citeaux. The abbey became too small for its members and it was necessary to send out bands to found new houses.[8] In 1118 Trois-Fontaines Abbey was founded in the diocese of Châlons; in 1119 Fontenay Abbey in the Diocese of Autun; and in 1121 Foigny Abbey near Vervins, in the diocese of Laon. In addition to these victories, Bernard also had his trials. During an absence from Clairvaux, the Grand Prior of the Abbey of Cluny went to Clairvaux and enticed away Bernard's cousin, Robert of Châtillon. This was the occasion of the longest and most emotional of Bernard's letters.[4]

In the year 1119, Bernard was present at the first general chapter of the order convoked by Stephen of Cîteaux. Though not yet 30 years old, Bernard was listened to with the greatest attention and respect, especially when he developed his thoughts upon the revival of the primitive spirit of regularity and fervour in all the monastic orders. It was this general chapter that gave definitive form to the constitutions of the order and the regulations of the Charter of Charity, which Pope Callixtus II confirmed on 23 December 1119. In 1120, Bernard wrote his first work, De Gradibus Superbiae et Humilitatis, and his homilies which he entitled De Laudibus Mariae. The monks of the abbey of Cluny were unhappy to see Cîteaux take the lead role among the religious orders of the Roman Catholic Church. For this reason, the Black Monks attempted to make it appear that the rules of the new order were impracticable. At the solicitation of William of St. Thierry, Bernard defended the order by publishing his Apology which was divided into two parts. In the first part, he proved himself innocent of the charges of Cluny and in the second he gave his reasons for his counterattacks. He protested his profound esteem for the Benedictines of Cluny whom he declared he loved equally as well as the other religious orders. Peter the Venerable, abbot of Cluny, answered Bernard and assured him of his great admiration and sincere friendship. In the meantime Cluny established a reform, and Abbot Suger, the minister of Louis VI of France, was converted by the Apology of Bernard. He hastened to terminate his worldly life and restore discipline in his monastery. The zeal of Bernard extended to the bishops, the clergy, and lay people. Bernard's letter to the archbishop of Sens was seen as a real treatise, "De Officiis Episcoporum." About the same time he wrote his work on Grace and Free Will.[4]

Doctor of the Church (1128–46)

In the year 1128 AD, Bernard participated in the Council of Troyes, which had been convoked by Pope Honorius II, and was presided over by Cardinal Matthew of Albano. The purpose of this council was to settle certain disputes of the bishops of Paris, and regulate other matters of the Church of France. The bishops made Bernard secretary of the council, and charged him with drawing up the synodal statutes. After the council, the bishop of Verdun was deposed. It was at this council that Bernard traced the outlines of the Rule of the Knights Templar who soon became the ideal of Christian nobility. Around this time, he praised them in his Liber ad milites templi de laude novae militiae.[9]

Again reproaches arose against Bernard and he was denounced, even in Rome. He was accused of being a monk who meddled with matters that did not concern him. Cardinal Harmeric, on behalf of the pope, wrote Bernard a sharp letter of remonstrance stating, "It is not fitting that noisy and troublesome frogs should come out of their marshes to trouble the Holy See and the cardinals."[4]

Bernard answered the letter by saying that, if he had assisted at the council, it was because he had been dragged to it by force, replying:

Now illustrious Harmeric if you so wished, who would have been more capable of freeing me from the necessity of assisting at the council than yourself? Forbid those noisy troublesome frogs to come out of their holes, to leave their marshes ... Then your friend will no longer be exposed to the accusations of pride and presumption.[4]

This letter made a positive impression on Harmeric, and in the Vatican.

Schism

Bernard's influence was soon felt in provincial affairs. He defended the rights of the Church against the encroachments of kings and princes, and recalled to their duty Henri Sanglier, archbishop of Sens and Stephen of Senlis, bishop of Paris. On the death of Honorius II, which occurred on 14 February 1130, a schism broke out in the Church by the election of two popes, Pope Innocent II and Antipope Anacletus II. Innocent II, having been banished from Rome by Anacletus, took refuge in France. Louis VI convened a national council of the French bishops at Étampes, and Bernard, summoned there by consent of the bishops, was chosen to judge between the rival popes. He decided in favour of Innocent II. After the council of Étampes, Bernard spoke with King Henry I of England, also known as Henry Beauclerc, about Henry I's reservations regarding Pope Innocent II. Henry I was sceptical because most of the bishops of England supported Antipope Anacletus II; Bernard persuaded him to support Innocent. This caused the pope to be recognized by all the great powers.

He then went with him into Italy and reconciled Pisa with Genoa, and Milan with the pope. The same year Bernard was again at the Council of Reims at the side of Innocent II. He then went to Aquitaine where he succeeded for the time in detaching William X, Duke of Aquitaine, from the cause of Anacletus.[5]

Germany had decided to support Innocent through Norbert of Xanten, who was a friend of Bernard's. However, Innocent insisted on Bernard's company when he met with Lothair II, Holy Roman Emperor. Lothair II became Innocent's strongest ally among the nobility. Although the councils of Étampes, Würzburg, Clermont, and Rheims all supported Innocent, large portions of the Christian world still supported Anacletus.

In a letter by Bernard to German Emperor Lothair regarding Antipope Anacletus, Bernard wrote, “It is a disgrace for Christ that a Jew sits on the throne of St. Peter’s.” and “Anacletus has not even a good reputation with his friends, while Innocent is illustrious beyond all doubt.”

Bernard wrote to Gerard of Angoulême (a letter known as Letter 126), which questioned Gerard's reasons for supporting Anacletus. Bernard later commented that Gerard was his most formidable opponent during the whole schism. After persuading Gerard, Bernard traveled to visit William X, Duke of Aquitaine. He was the hardest for Bernard to convince. He did not pledge allegiance to Innocent until 1135. After that, Bernard spent most of his time in Italy persuading the Italians to pledge allegiance to Innocent. He traveled to Sicily in 1137 to convince the king of Sicily to follow Innocent. The whole conflict ended when Anacletus died on 25 January 1138.[10]

In 1132, Bernard accompanied Innocent II into Italy, and at Cluny the pope abolished the dues which Clairvaux used to pay to that abbey. This action gave rise to a quarrel between the White Monks and the Black Monks which lasted 20 years. In May of that year, the pope, supported by the army of Lothair III, entered Rome, but Lothair III, feeling himself too weak to resist the partisans of Anacletus, retired beyond the Alps, and Innocent sought refuge in Pisa in September 1133. Bernard had returned to France in June and was continuing the work of peacemaking which he had commenced in 1130. Towards the end of 1134, he made a second journey into Aquitaine, where William X had relapsed into schism. Bernard invited William to the Mass which he celebrated in the Church of La Couldre. At the Eucharist, he "admonished the Duke not to despise God as he did His servants".[4] William yielded and the schism ended. Bernard went again to Italy, where Roger II of Sicily was endeavouring to withdraw the Pisans from their allegiance to Innocent. He recalled the city of Milan to obedience to the pope as they had followed the deposed Anselm V, Archbishop of Milan. For this, he was offered, and he refused, the archbishopric of Milan. He then returned to Clairvaux. Believing himself at last secure in his cloister, Bernard devoted himself with renewed vigour to the composition of the works which won for him the title of "Doctor of the Church". He wrote at this time his sermons on the Song of Songs.[lower-alpha 2] In 1137, he was again forced to leave his solitude by order of the pope to put an end to the quarrel between Lothair and Roger of Sicily. At the conference held at Palermo, Bernard succeeded in convincing Roger of the rights of Innocent II. He also silenced the final supporters who sustained the schism. Anacletus died of "grief and disappointment" in 1138, and with him the schism ended.[4]

In 1139, Bernard assisted at the Second Council of the Lateran, in which the surviving adherents of the schism were definitively condemned. About the same time, Bernard was visited at Clairvaux by Malachy, Primate of All Ireland, and a very close friendship formed between them. Malachy wanted to become a Cistercian, but the pope would not give his permission. Malachy died at Clairvaux in 1148.[4]

Contest with Abelard

Towards the close of the 11th century, a spirit of independence flourished within schools of philosophy and theology. This led for a time to the exaltation of human reason and rationalism. The movement found an ardent and powerful advocate in Peter Abelard. Abelard's treatise on the Trinity had been condemned as heretical in 1121, and he was compelled to throw his own book into the fire. However, Abelard continued to develop his teachings, which were controversial in some quarters. Bernard, informed of this by William of St-Thierry, is said to have held a meeting with Abelard intending to persuade him to amend his writings, during which Abelard repented and promised to do so. But once out of Bernard's presence, he reneged.[12] Bernard then denounced Abelard to the pope and cardinals of the Curia. Abelard sought a debate with Bernard, but Bernard initially declined, saying he did not feel matters of such importance should be settled by logical analyses. Bernard's letters to William of St-Thierry also express his apprehension about confronting the preeminent logician. Abelard continued to press for a public debate, and made his challenge widely known, making it hard for Bernard to decline. In 1141, at the urgings of Abelard, the archbishop of Sens called a council of bishops, where Abelard and Bernard were to put their respective cases so Abelard would have a chance to clear his name.[12] Bernard lobbied the prelates on the evening before the debate, swaying many of them to his view. The next day, after Bernard made his opening statement, Abelard decided to retire without attempting to answer.[12] The council found in favour of Bernard and their judgment was confirmed by the pope. Abelard submitted without resistance, and he retired to Cluny to live under the protection of Peter the Venerable, where he died two years later.[5]

Cistercian Order and heresy

Bernard had occupied himself in sending bands of monks from his overcrowded monastery into Germany, Sweden, England, Ireland, Portugal, Switzerland, and Italy. Some of these, at the command of Innocent II, took possession of Tre Fontane Abbey, from which Eugene III was chosen in 1145. Pope Innocent II died in the year 1143. His two successors, Pope Celestine II and Pope Lucius II, reigned only a short time, and then Bernard saw one of his disciples, Bernard of Pisa, and known thereafter as Eugene III, raised to the Chair of Saint Peter.[13] Bernard sent him, at the pope's own request, various instructions which comprise the Book of Considerations, the predominating idea of which is that the reformation of the Church ought to commence with the sanctity of the pope. Temporal matters are merely accessories; the principles according to Bernard's work were that piety and meditation were to precede action.[14]

Having previously helped end the schism within the Church, Bernard was now called upon to combat heresy. Henry of Lausanne, a former Cluniac monk, had adopted the teachings of the Petrobrusians, followers of Peter of Bruys and spread them in a modified form after Peter's death.[15] Henry of Lausanne's followers became known as Henricians. In June 1145, at the invitation of Cardinal Alberic of Ostia, Bernard traveled in southern France.[16] His preaching, aided by his ascetic looks and simple attire, helped doom the new sects. Both the Henrician and the Petrobrusian faiths began to die out by the end of that year. Soon afterwards, Henry of Lausanne was arrested, brought before the bishop of Toulouse, and probably imprisoned for life. In a letter to the people of Toulouse, undoubtedly written at the end of 1146, Bernard calls upon them to extirpate the last remnants of the heresy. He also preached against Catharism.[13]

Second Crusade (1146–49)

News came at this time from the Holy Land that alarmed Christendom. Christians had been defeated at the Siege of Edessa and most of the county had fallen into the hands of the Seljuk Turks.[17] The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the other Crusader states were threatened with similar disaster. Deputations of the bishops of Armenia solicited aid from the pope, and the King of France also sent ambassadors. In 1144 Eugene III commissioned Bernard to preach the Second Crusade[6] and granted the same indulgences for it which Pope Urban II had accorded to the First Crusade.[18]

There was at first virtually no popular enthusiasm for the crusade as there had been in 1095. Bernard found it expedient to dwell upon taking the cross as a potent means of gaining absolution for sin and attaining grace. On 31 March, with King Louis VII of France present, he preached to an enormous crowd in a field at Vézelay, making "the speech of his life".[19] The full text has not survived, but a contemporary account says that "his voice rang out across the meadow like a celestial organ"[19]

James Meeker Ludlow describes the scene romantically in his book The Age of the Crusades:

A large platform was erected on a hill outside the city. King and monk stood together, representing the combined will of earth and heaven. The enthusiasm of the assembly of Clermont in 1095, when Peter the Hermit and Urban II launched the first crusade, was matched by the holy fervor inspired by Bernard as he cried, "O ye who listen to me! Hasten to appease the anger of heaven, but no longer implore its goodness by vain complaints. Clothe yourselves in sackcloth, but also cover yourselves with your impenetrable bucklers. The din of arms, the danger, the labors, the fatigues of war, are the penances that God now imposes upon you. Hasten then to expiate your sins by victories over the Infidels, and let the deliverance of the holy places be the reward of your repentance." As in the olden scene, the cry "Deus vult! Deus vult! " rolled over the fields, and was echoed by the voice of the orator: "Cursed be he who does not stain his sword with blood."[20]

When Bernard was finished the crowd enlisted en masse; they supposedly ran out of cloth to make crosses. Bernard is said to have flung off his own robe and began tearing it into strips to make more.[18][19] Others followed his example and he and his helpers were supposedly still producing crosses as night fell.[19]

Unlike the First Crusade, the new venture attracted royalty, such as Eleanor of Aquitaine, Queen of France; Thierry of Alsace, Count of Flanders; Henry, the future Count of Champagne; Louis's brother Robert I of Dreux; Alphonse I of Toulouse; William II of Nevers; William de Warenne, 3rd Earl of Surrey; Hugh VII of Lusignan, Yves II, Count of Soissons; and numerous other nobles and bishops. But an even greater show of support came from the common people. Bernard wrote to the pope a few days afterwards, "Cities and castles are now empty. There is not left one man to seven women, and everywhere there are widows to still-living husbands."[18]

Bernard then passed into Germany, and the reported miracles which multiplied almost at his every step undoubtedly contributed to the success of his mission. Conrad III of Germany and his nephew Frederick Barbarossa, received the cross from the hand of Bernard.[17] Pope Eugenius came in person to France to encourage the enterprise. As in the First Crusade, the preaching led to attacks on Jews; a fanatical French monk named Radulphe was apparently inspiring massacres of Jews in the Rhineland, Cologne, Mainz, Worms, and Speyer, with Radulphe claiming Jews were not contributing financially to the rescue of the Holy Land. The archbishop of Cologne and the archbishop of Mainz were vehemently opposed to these attacks and asked Bernard to denounce them. This he did, but when the campaign continued, Bernard traveled from Flanders to Germany to deal with the problems in person. He then found Radulphe in Mainz and was able to silence him, returning him to his monastery.[21]

The last years of Bernard's life were saddened by the failure of the Second Crusade he had preached, the entire responsibility for which was thrown upon him.[13] Bernard considered it his duty to send an apology to the Pope and it is inserted in the second part of his "Book of Considerations." There he explains how the sins of the crusaders were the cause of their misfortune and failures.

Moved by his burning words, many Christians embarked for the Holy Land, but the crusade ended in miserable failure.[6]

Final years (1149–53)

The death of his contemporaries served as a warning to Bernard of his own approaching end. The first to die was Suger in 1152, of whom Bernard wrote to Eugene III, "If there is any precious vase adorning the palace of the King of Kings it is the soul of the venerable Suger". Conrad III and his son Henry died the same year. From the beginning of the year 1153, Bernard felt his death approaching. The passing of Pope Eugenius had struck the fatal blow by taking from him one whom he considered his greatest friend and consoler. Bernard died at age sixty-three on 20 August 1153, after forty years spent in the cloister.[13] He was buried at the Clairvaux Abbey, but after its dissolution in 1792 by the French revolutionary government, his remains were transferred to Troyes Cathedral.

Theology

Bernard was named a Doctor of the Church in 1830. At the 800th anniversary of his death, Pope Pius XII issued an encyclical on Bernard, Doctor Mellifluus, in which he labeled him "The Last of the Fathers." Bernard did not reject human philosophy which is genuine philosophy, which leads to God; he differentiates between different kinds of knowledge, the highest being theological. The central elements of Bernard's Mariology are how he explained the virginity of Mary, the "Star of the Sea", and her role as Mediatrix.

The first abbot of Clairvaux developed a rich theology of sacred space and music, writing extensively on both.

John Calvin quotes Bernard several times[22] in support of the doctrine of Sola Fide,[23] which Martin Luther described as the article upon which the church stands or falls.[24] Calvin also quotes him in setting forth his doctrine of a forensic alien righteousness, or as it is commonly called imputed righteousness.[25]

Temptations and intercessions

One day, to cool down his lustful temptation, Bernard threw himself into ice-cold water. Another time, while he slept in an inn, a prostitute was introduced naked beside him, and he saved his chastity by running.[6]

Many miracles were attributed to his intercession. One time he restored the power of speech to an old man that he might confess his sins before he died. Another time, an immense number of flies, that had infested the Church of Foigny, died instantly after the excommunication he made on them.[6]

So great was his reputation that princes and Popes sought his advice, and even the enemies of the Church admired the holiness of his life and the greatness of his writings.[6]

Spirituality

Bernard was instrumental in re-emphasizing the importance of lectio divina and contemplation on Scripture within the Cistercian order. Bernard had observed that when lectio divina was neglected monasticism suffered. Bernard considered lectio divina and contemplation guided by the Holy Spirit the keys to nourishing Christian spirituality.[26]

Bernard "noted centuries ago: the people who are their own spiritual directors have fools for disciples."[27]

Legacy

Bernard's theology and Mariology continue to be of major importance, particularly within the Cistercian and Trappist orders.[lower-alpha 3] Bernard led to the foundation of 163 monasteries in different parts of Europe. At his death, they numbered 343. His influence led Alexander III to launch reforms that led to the establishment of canon law.[28] He was the first Cistercian monk placed on the calendar of saints and was canonized by Alexander III 18 January 1174.[29] Pope Pius VIII bestowed on him the title "Doctor of the Church". He is labeled the "Mellifluous Doctor" for his eloquence. Cistercians honour him as the founder of the order because of the widespread activity which he gave to the order.[13]

His feast day is 20 August.

Bernard's "Prayer to the Shoulder Wound of Jesus" is often published in Catholic prayer books.

Bernard is Dante Alighieri's last guide, in Divine Comedy, as he travels through the Empyrean.[30] Dante's choice appears to be based on Bernard's contemplative mysticism, his devotion to Mary, and his reputation for eloquence.[31]

The Couvent et Basilique Saint-Bernard, a collection of buildings dating from the 12th, 17th and 19th centuries, is dedicated to Bernard and stands in his birthplace of Fontaine-lès-Dijon.[32]

Hymns

Bernard of Clairvaux is the attributed author of poems often translated in English hymnals as:

- "O Sacred Head, Now Wounded"

- "Jesus the Very Thought of Thee"

- "Jesus, Thou Joy of Loving Hearts"

Works

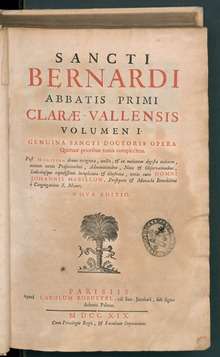

The modern critical edition is Sancti Bernardi opera (1957–1977), edited by Jean Leclercq.[33][lower-alpha 4]

Bernard's works include:

- De gradibus humilitatis et superbiae [The steps of humility and pride] (in Latin). c. 1120. his first treatise.[34]

- Apologia ad Guillelmum Sancti Theoderici Abbatem [Apology to William of St. Thierry] (in Latin). Written in the defence of the Cistercians against the claims of the monks of Cluny.[35]

- De conversione ad clericos sermo seu liber [On the conversion of clerics] (in Latin). 1122. A book addressed to the young ecclesiastics of Paris.[36]

- De gratia et libero arbitrio [On grace and free choice] (in Latin). c. 1128. in which the Roman Catholic dogma of grace and free will was defended according to the principles of St Augustine.[37]

- De diligendo Dei [On loving God] (in Latin). Outlines seven stages of ascent leading to union with God.[38]

- Liber ad milites templi de laude novae militiae [In Praise of the new knighthood] (in Latin). 1129. addressed to Hugues de Payens, first Grand Master and Prior of Jerusalem. This is a eulogy of the Knights Templar order, which had been instituted in 1118, and an exhortation to the knights to conduct themselves with courage in their several stations.[39]

- De praecepto et dispensatione libri [Book of precepts and dispensations] (in Latin). c. 1144. Answers questions about which parts of Rule of Saint Benedict an abbot can, or cannot, dispense.[40]

- De consideratione [On consideration] (in Latin). c. 1150. Addressed to Pope Eugene III.[41]

- Liber De vita et rebus gestis Sancti Malachiae Hiberniae Episcopi [The life and death of Saint Malachy, bishop of Ireland] (in Latin). [42]

- De moribus et officio episcoporum (in Latin). A letter to Henri Sanglier, Archbishop of Sens on the duties of bishops.[43]

His sermons are also numerous:

- Most famous are his Sermones super Cantica Canticorum (Sermons on the Song of Songs). Although it has at times been suggested that the sermon form is a rhetorical device in a set of works which were only ever designed to be read, since such finely polished and lengthy literary pieces could not accurately have been recorded by a monk while Bernard was preaching, recent scholarship has tended toward the theory that, although what exists in these texts was certainly the product of Bernard's writing, they likely found their origins in sermons preached to the monks of Clairvaux.[lower-alpha 5] Bernard began to write these in 1135 but died without completing the series, with 86 sermons complete. These sermons contain an autobiographical passage, sermon 26, mourning the death of his brother, Gerard.[44][45] After Bernard died, the English Cistercian Gilbert of Hoyland continued Bernard's incomplete series of 86 sermons on the biblical Song of Songs. Gilbert wrote 47 sermons before he died in 1172, taking the series up to Chapter 5 of the Song of Songs. Another English Cistercian abbot, John of Ford, wrote another 120 sermons on the Song of Songs, so completing the Cistercian sermon-commentary on the book.

- There are 125 surviving Sermones per annum (Sermons on the Liturgical Year).

- There are also the Sermones de diversis (Sermons on Different Topics).

- 547 letters survive.[46]

Many letters, treatises, and other works, falsely attributed to him survive, and are now referred to as works by pseudo-Bernard.[4] These include:

- pseudo-Bernard (pseud. of Guigo I) (c. 1150). L'échelle du cloître [The scale of the cloister] (letter) (in French).[4]

- pseudo-Bernard. Meditatio [Meditations] (in Latin). This was probably written at some point in the thirteenth century. It circulated extensively in the Middle Ages under Bernard's name and was one of the most popular religious works of the later Middle Ages. Its theme is self-knowledge as the beginning of wisdom; it begins with the phrase "Many know much, but do not know themselves".[47][48][4]

- pseudo-Bernard. L'édification de la maison intérieure (in French).[4]

Translations

- On consideration, trans George Lewis, (Oxford, 1908) https://books.google.com/books?id=kkoJAQAAIAAJ

- Select treatises of S. Bernard of Clairvaux: De diligendo Deo & De gradibus humilitatis et superbiae, (Cambridge: CUP, 1926)

- On loving God, and selections from sermons, edited by Hugh Martin, (London: SCM Press, 1959) [reprinted as (Westport, CO: Greenwood Press, 1981)]

- Cistercians and Cluniacs: St. Bernard's Apologia to Abbot William, trans M Casey. Cistercian Fathers series no. 1, (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1970)

- The works of Bernard of Clairvaux. Vol.1, Treatises, 1, edited by M. Basil Pennington. Cistercian Fathers Series, no. 1. (Spencer, Mass.: Cistercian Publications, 1970) [contains the treatises Apologia to Abbot William and On Precept and Dispensation, and two shorter liturgical treatises]

- Bernard of Clairvaux, On the Song of Songs, 4 vols, Cistercian Fathers series nos 4, 7, 31, 40, (Spencer, MA: Cistercian Publications, 1971–80)

- Letter of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux on revision of Cistercian chant = Epistola S[ancti] Bernardi de revisione cantus Cisterciensis, edited and translated by Francis J. Guentner, (American Institute of Musicology, 1974)

- Treatises II : The steps of humility and pride on loving God, Cistercian Fathers series no. 13, (Washington: Cistercian Publications, 1984)

- Five books on consideration: advice to a Pope, translated by John D. Anderson & Elizabeth T. Kennan. Cistercian Fathers Series no. 37. (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1976)

- The Works of Bernard of Clairvaux. Volume Seven, Treatises III: On Grace and free choice. In praise of the new knighthood, translated by Conrad Greenia. Cistercian Fathers Series no. 19, (Kalamazoo, Michigan: Cistercian Publications Inc., 1977)

- The life and death of Saint Malachy, the Irishman translated and annotated by Robert T. Meyer, (Kalamazoo, Mich: Cistercian Publications, 1978)

- Bernard of Clairvaux, Homiliae in laudibus Virginis Matris, in Magnificat: homilies in praise of the Blessed Virgin Mary translated by Marie-Bernard Saïd and Grace Perigo, Cistercian Fathers Series no. 18, (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1979)

- Sermons on Conversion: on conversion, a sermon to clerics and Lenten sermons on the psalm "He Who Dwells"., Cistercian Fathers Series no. 25, (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1981)

- Bernard of Clairvaux, Song of Solomon, translated by Samuel J. Eales, (Minneapolis, MN: Klock & Klock, 1984)

- St. Bernard's sermons on the Blessed Virgin Mary, translated from the original Latin by a priest of Mount Melleray, (Chumleigh: Augustine, 1984)

- Bernard of Clairvaux, The twelve steps of humility and pride; and, On loving God, edited by Halcyon C. Backhouse, (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1985)

- St. Bernard's sermons on the Nativity, translated from the original Latin by a priest of Mount Melleray, (Devon: Augustine, 1985)

- Bernard of Clairvaux : selected works, translation and foreword by G.R. Evans; introduction by Jean Leclercq; preface by Ewert H. Cousins, (New York: Paulist Press, 1987) [Contains the treatises On conversion, On the steps of humility and pride, On consideration, and On loving God; extracts from Sermons on The song of songs, and a selection of letters]

- Conrad Rudolph, The 'Things of Greater Importance': Bernard of Clairvaux's Apologia and the Medieval Attitude Toward Art, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990) [Includes the Apologia in both Leclercq's Latin text and English translation]

- Love without measure: extracts from the writings of St Bernard of Clairvaux, introduced and arranged by Paul Diemer, Cistercian studies series no. 127, (Kalamazoo, Mich. : Cistercian Publications, 1990)

- Sermons for the summer season: liturgical sermons from Rogationtide and Pentecost, translated by Beverly Mayne Kienzle; additional translations by James Jarzembowski, (Kalamazoo, Mich: Cistercian Publications, 1991)

- Bernard of Clairvaux, On loving God, Cistercian Fathers series no. 13B, (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1995)

- Bernard of Clairvaux, The parables & the sentences, edited by Maureen M. O'Brien. Cistercian Fathers Series no. 55, (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 2000)

- Bernard of Clairvaux, On baptism and the office of bishops, on the conduct and office of bishops, on baptism and other questions: two letter-treatises, translated by Pauline Matarasso. Cistercian Fathers Series no. 67, (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 2004)

- Bernard of Clairvaux, Sermons for Advent and the Christmas season translated by Irene Edmonds, Wendy Mary Beckett, Conrad Greenia; edited by John Leinenweber; introduction by Wim Verbaal. Cistercian Fathers Series no. 51, (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 2007)

- Bernard of Clairvaux, Sermons for Lent and the Easter Season, edited by John Leinenweber and Mark Scott, OCSO. Cistercian Fathers Series no. 52, (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 2013)

See also

- List of Catholic saints

- List of Latin nicknames of the Middle Ages: Doctors in theology

- Scholasticism

- St. Bernard de Clairvaux Church

- Prayer to the shoulder wound of Jesus

- Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, patron saint archive

Notes

- André de Montbard, one of the founders of the Knights Templar, was a half-brother of Bernard's mother.

- Other mystics such as John of the Cross also found their language and symbols in Song of Songs.[11]

- His texts are prescribed readings in Cistercian congregations.

- For a research guide see McGuire (2013).

- For a history of the debate over the Sermons, and an attempted solution, see Leclercq, Jean. "Introduction". In Walsh (1976), pp. vii–xxx.

Citations

- "Holy Men and Holy Women" (PDF). Churchofengland.org.

- "Notable Lutheran Saints". Resurrectionpeople.org.

- Smith, William (2010). Catholic Church Milestones: People and Events That Shaped the Institutional Church. Indianapolis: Left Coast. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-60844-821-0.

- Gildas 1907.

- Bunson, Bunson & Bunson 1998, p. 129.

- Pirlo 1997.

- McManners 1990, p. 204.

- "Expositio in Apocalypsim". Cambridge Digital Library (manuscript). Cambridge Digital Library. MS Mm.5.31. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- Durant (1950) p.593.

- Cristiani, Léon. St. Bernard of Clairvaux, 1090-1153. Translated by Bouchard, M. Angeline. Boston: St. Paul Editions. OCLC 2874038.

- Cunningham & Egan 1996, p. 128.

- Evans 2000, pp. 115–123.

- Bunson, Bunson & Bunson 1998, p. 130.

- McManners 1990, p. 210.

- Alphandéry 1911, pp. 298–299.

- McManners 1990, p. 211.

- Riley-Smith 1991, p. 48.

- Durant (1950) p.594.

- NORWICH, JOHN JU (2012). The Popes: A History. London: Vintage. ISBN 9780099565871.

- Ludlow 1896, pp. 164-167.

- Durant (1950) p. 391.

- Lane, Anthony N. S. (1999). John Calvin: student of the church fathers. Edinburgh: T & T Clark. p. 100. ISBN 9780567086945.

- Calvin 1960, bk.3 ch.2 §25, bk.3 ch.12 §3.

- Luther 1930, p. 130.

- Calvin 1960, bk.3 ch.11 §22, bk.3 ch.25 §2.

- Cunningham & Egan 1996, pp. 91–92.

- Cunningham & Egan 1996, p. 21.

- Duffy 1997, p. 101.

- Kemp, E. W. (1945). "Pope Alexander III and the Canonization of Saints: The Alexander Prize Essay". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 27: 13–28. doi:10.2307/3678572. ISSN 0080-4401. JSTOR 3678572.

- Paradiso, cantos XXXI–XXXIII

- Botterill 1994.

- "Monuments historiques : Couvent et Basilique Saint-Bernard", Mérimée (in French), Ministère de la Culture, retrieved 21 July 2017

- SBOp.

- PL, 182, cols. 939–972c.

- PL, 182, cols. 893–918a.

- PL, 182, cols. 833–856d.

- PL, 182, cols. 999–1030a.

- PL, 182, cols. 971–1000b.

- PL, 182, cols. 917–940b.

- PL, 182, cols. 857–894c.

- PL, 182, cols. 727–808a.

- PL, 182, cols. 1073–1118a.

- Ep. 42 (PL, 182, cols. 807–834a).

- Verbaal 2004.

- PL, 183, cols. 785–1198A.

- SBOp, v. 7–8.

- PL, 184, cols. 485–508.

- Bestul 2012, p. 164.

References

![]()

- Alphandéry, Paul D. (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 298–299.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bernard of Clairvaux (1976). On the Song of Songs II. Cistercian Fathers series. 7. Translated by Walsh, Kilian. Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications. ISBN 9780879077075. OCLC 2621974.

- Bernard of Clairvaux (1998). The letters of St Bernard of Clairvaux. Cistercian Fathers series. 62. Translated by James, Bruno Scott. Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications. ISBN 9780879071622.

- Bernard of Clairvaux. Mabillon, Jean (ed.). Opera omnia. Patrologia Latina (in Latin). 182–185. Paris: Jacques Paul Migne. 6 tomes in 4 volumes.

- Bernard of Clairvaux (1957–1977). Leclerq, Jean; Talbot, Charles H.; Rochais, Henri Marie (eds.). Sancti Bernardi Opera (in Latin). 8 volumes in 9. Rome: Éditions cisterciennes. OCLC 654190630.

- Bestul, Thomas H (2012). "Meditatio/Meditation". In Hollywood, Amy; Beckman, Patricia Z. (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Christian Mysticism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521863650.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Botterill, Steven (1994). Dante and the Mystical Tradition: Bernard of Clairvaux in the Commedia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bunson, Matthew; Bunson, Margaret & Bunson, Stephen (1998). Our Sunday Visitor's Encyclopedia of Saints. Huntington: Our Sunday Visitor.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Calvin, John (1960). McNeill, John T. (ed.). Institutes of the Christian Religion. 1. Translated by Battles, Ford Lewis. Philadelphia: Westminster Press. OCLC 844778472.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cantor, Norman (1994). The Civilization of the Middle Ages. New York: HarperPerennial. ISBN 0-06-092553-1.

- Cunningham, Lawrence S.; Egan, Keith J. (1996). "Meditation and contemplation". Christian spirituality: themes from the tradition. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-3660-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Duffy, Eamon (1997). Saints and Sinners, a History of the Popes.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evans, Gillian R. (2000). Bernard of Clairvaux (Great Medieval Thinkers). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512525-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 795–798.

- Gilson, Etienne (1940). The mystical theology of St Bernard. London: Sheed & Ward.

- Ludlow, James Meeker (1896). The Age of the Crusades. Ten epochs of church history. 6. New York: Christian Literature. OCLC 904364803.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Luther, Martin (1930). D. Martin Luthers Werke: kritische Gesammtausgabe (in German and Latin). 40. Weimar: Herman Böhlau.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McGuire, Brian Patrick (30 September 2013). "Bernard of Clairvaux". oxfordbibliographies.com. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780195396584-0088. Missing or empty

|url=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - McManners, John (1990). The Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822928-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Most, William G. (1996). "Mary's Immaculate Conception". ewtn.com. Irondale, AL: Eternal Word Television Network. Archived from the original on 19 February 1998. Retrieved 23 February 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Adapted from Most, William G. (1994). Our Lady in doctrine and devotion. Alexandria, VA: Notre Dame Institute Press. OCLC 855913595.

- Pirlo, Paolo O. (1997). "St. Bernard". My first book of saints. Sons of Holy Mary Immaculate - Quality Catholic Publications. pp. 186–188. ISBN 971-91595-4-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1991). The Atlas of the Crusades. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-2186-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Runciman, Steven (1987). The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100–1187. A History of the Crusades. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-34771-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Verbaal, Wim (2004). "Preaching the dead from their graves: Bernard of Clairvaux's Lament on his brother Gerard". In Donavin, Georgiana; Nederman, Cary; Utz, Richard (eds.). Speculum sermonis: interdisciplinary reflections on the medieval sermon. Disputatio. 1. Turnhout: Brepols. pp. 113–139. doi:10.1484/M.DISPUT-EB.3.1616. ISBN 9782503513393.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Allestree, Richard (1684). "Sermon | 13. | The Believers Concern | to pray for Faith. | Mark 9. 24. | Lord, I believe, help thou my Unbelief.". Forty sermons, whereof twenty one are now first publish'd, the greatest part preach'd before the King and on solemn occasions. Oxford; London: for R. Scott, G. Wells, T. Sawbridge, R. Bentley. p. 188. OCLC 659408239. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bernard of Clairvaux. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Bernard of Clairvaux |

- Works by Bernard of Clairvaux at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Bernard of Clairvaux at Internet Archive

- Works by Bernard of Clairvaux at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "St. Bernard, Abbot", Butler's Lives of the Saints

- Opera omnia Sancti Bernardi Claraevallensis his complete works, in Latin

- Audio on the life of St. Bernard of Clairvaux from waysideaudio.com

- Database with all known medieval representations of Bernard

- Saint Bernard of Clairvaux at the Christian Iconography web site.

- "Here Followeth the Life of St. Bernard, the Mellifluous Doctor" from the Caxton translation of the Golden Legend

- "Two Accounts of the Early Career of St. Bernard" by William of Thierry and Arnold of Bonneval

- Saint Bernard of Clairvaux Abbot, Doctor of the Church-1153 at EWTN Global Catholic Network

- Colonnade Statue St Peter's Square

- Lewis E 26 De consideratione (On Consideration) at OPenn

- MS 484/11 Super cantica canticorum at OPenn