Book of Revelation

The Book of Revelation (often called the Revelation to John, Apocalypse of John, the Revelation from Jesus Christ (from its opening words), the Apocalypse, The Revelation, or simply Revelation) is the final book of the New Testament, and consequently is also the final book of the Christian Bible. Its title is derived from the first word of the Koine Greek text: apokalypsis, meaning "unveiling" or "revelation" (before title pages and titles, books were commonly known by their incipit (first words), as is also the case with the Hebrew Torah). The Book of Revelation is the only apocalyptic document in the New Testament canon (although there are short apocalyptic passages in various places in the Gospels and the Epistles, and an extended apocalyptic passage in the Book of Daniel in the Old Testament).[lower-alpha 1] Thus, it occupies a central place in Christian eschatology.

| Books of the New Testament |

|---|

|

| Gospels |

| Acts |

| Acts of the Apostles |

| Epistles |

|

Romans 1 Corinthians · 2 Corinthians Galatians · Ephesians Philippians · Colossians 1 Thessalonians · 2 Thessalonians 1 Timothy · 2 Timothy Titus · Philemon Hebrews · James 1 Peter · 2 Peter 1 John · 2 John · 3 John Jude |

| Apocalypse |

| Revelation |

| New Testament manuscripts |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| John in the Bible |

|---|

Saint John the Evangelist, Domenichino |

| Johannine literature |

|

| Authorship |

|

| Related literature |

|

| See also |

|

The author names himself as "John" in the text, but his precise identity remains a point of academic debate. Second-century Christian writers such as Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Melito (the bishop of Sardis), Clement of Alexandria, and the author of the Muratorian fragment identify John the Apostle as the "John" of Revelation.[1] Modern scholarship generally takes a different view,[2] with many considering that nothing can be known about the author except that he was a Christian prophet.[3] Some modern scholars characterize Revelation's author as a putative figure whom they call "John of Patmos". The bulk of traditional sources date the book to the reign of the Roman emperor Domitian (AD 81–96), which evidence tends to confirm.[4][lower-alpha 2]

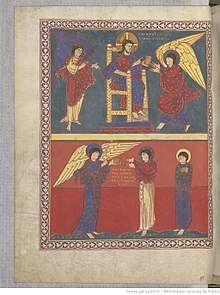

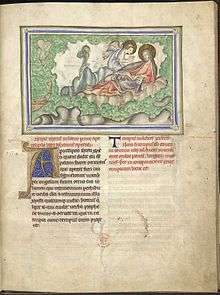

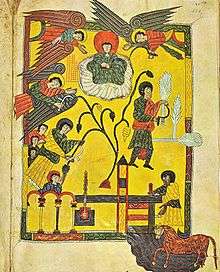

The book spans three literary genres: the epistolary, the apocalyptic, and the prophetic.[6] It begins with John, on the island of Patmos in the Aegean Sea, addressing a letter to the "Seven Churches of Asia". He then describes a series of prophetic visions, including of figures such as the Seven-Headed Dragon, the Serpent, and the Beast, which culminate in the Second Coming of Jesus.

The obscure and extravagant imagery has led to a wide variety of Christian interpretations. Historicist interpretations see Revelation as containing a broad view of history, whilst preterist interpretations treat Revelation as mostly referring to the events of the Apostolic Age (1st century), or, at the latest, the fall of the Roman Empire. Futurists, meanwhile, believe that Revelation describes future events, with the seven churches growing into the body/believers throughout the age, and a reemergence or continuous rule of a Roman/Graeco system with modern capabilities described by John in ways familiar to him, and idealist or symbolic interpretations consider that Revelation does not refer to actual people or events, but is an allegory of the spiritual path and the ongoing struggle between good and evil.

Composition and setting

Title, authorship, and date

The name Revelation comes from the first word of the book in Koine Greek: ἀποκάλυψις (apokalypsis), which means "unveiling" or "revelation". The author names himself as "John", but modern scholars consider it unlikely that the author of Revelation also wrote the Gospel of John. Dionysius of Alexandria set out some of the evidence for this view as early as the second half of the third century, noting that the gospel and the epistles attributed to John, unlike Revelation, do not name their author, and that the Greek of the gospel is stylistically correct and elegant while that of Revelation is neither; some later scholars believe that the two books also have radical differences in theological perspective.[7]

Tradition ascribes the authorship to John the Apostle. Critics of the traditional identification doubt that the apostle could have lived into the most likely time for the book's composition, the reign of Domitian, and the author never states that he knew Jesus.[8] All that is known is that this John was a Jewish Christian prophet, probably belonging to a group of such prophets, and was accepted as such by the congregations to whom he addresses his letter.[4][9] His precise identity remains unknown,[10] and modern scholarship commonly refers to him as "John of Patmos" [11] (Revelation 1:9 – "I, John [...] was on the island called Patmos" (NRSV)).

The book is commonly dated to about 95 AD. The date is suggested by clues in the visions pointing to the reign of the emperor Domitian.[12] The beast with seven heads and the number 666 seem to allude directly to the emperor Nero (reigned AD 54–68), but this does not require that Revelation was written in the 60s, as there was a widespread belief in later decades that Nero would return.[13][4] No original manuscript exists, and some (particularly Greek Orthodox) believe it was originally written on the walls of a cave on Patmos, now a UNESCO World Heritage site called the Cave of the Apocalypse.

Genre

Revelation is an apocalyptic prophecy with an epistolary introduction addressed to seven churches in the Roman province of Asia.[3] "Apocalypse" means the revealing of divine mysteries;[14] John is to write down what is revealed (what he sees in his vision) and send it to the seven churches.[3] The entire book constitutes the letter—the letters to the seven individual churches are introductions to the rest of the book, which is addressed to all seven.[3] While the dominant genre is apocalyptic, the author sees himself as a Christian prophet: Revelation uses the word in various forms twenty-one times, more than any other New Testament book.[15]

Sources

The predominant view is that Revelation alludes to the Old Testament although it is difficult among scholars to agree on the exact number of allusions or the allusions themselves.[16] Revelation rarely quotes directly from the Old Testament, yet almost every verse alludes to or echoes older scriptures. Over half of the references stem from Daniel, Ezekiel, Psalms, and Isaiah, with Daniel providing the largest number in proportion to length and Ezekiel standing out as the most influential. Because these references appear as allusions rather than as quotes, it is difficult to know whether the author used the Hebrew or the Greek version of the Hebrew scriptures, but he was clearly often influenced by the Greek. He very frequently combines multiple references, and again the allusional style makes it impossible to be certain to what extent he did so consciously.[17]

Setting

Conventional understanding until recent times was that the Book of Revelation was written to comfort beleaguered Christians as they underwent persecution at the hands of a megalomaniacal Roman emperor, but much of this has now been jettisoned: Domitian is no longer viewed as a despot imposing an imperial cult, and it is no longer believed that there was any systematic empire-wide persecution of Christians in his time.[18] The current view is that Revelation was composed in the context of a conflict within the Christian community of Asia Minor over whether to engage with, or withdraw from, the far larger non-Christian community: Revelation chastises those Christians who wanted to reach an accommodation with the Roman cult of empire.[19] This is not to say that Christians in Roman Asia were not suffering, for withdrawal from, and defiance against, the wider Roman society, which imposed very real penalties; Revelation offered a victory over this reality by offering an apocalyptic hope: in the words of professor Adela Yarbro Collins, "What ought to be was experienced as a present reality."[20]

Canonical history

Revelation was among the last books accepted into the Christian biblical canon, and to the present day some churches that derive from the Church of the East reject it.[21][22] Eastern Christians became skeptical of the book as doubts concerning its authorship and unusual style[23] were reinforced by aversion to its acceptance by Montanists and other groups considered to be heretical.[24] This distrust of the Book of Revelation persisted in the East through the 15th century.[25]

Dionysius (248 AD), bishop of Alexandria and disciple of Origen, wrote that the Book of Revelation could have been written by Cerinthus although he himself did not adopt the view that Cerinthus was the writer. He regarded the Apocalypse as the work of an inspired man but not of an Apostle (Eusebius, Church History VII.25).[26]

Eusebius, in his Church History (c. 330 AD) mentioned that the Apocalypse of John was accepted as a Canonical book and rejected at the same time:

- 1. ... it is proper to sum up the writings of the New Testament which have been already mentioned... After them is to be placed, if it really seem proper, the Apocalypse of John, concerning which we shall give the different opinions at the proper time. These then belong among the accepted writings [Homologoumena].

- 4. Among the rejected [Kirsopp. Lake translation: "not genuine"] writings must be reckoned, as I said, the Apocalypse of John, if it seem proper, which some, as I said, reject, but which others class with the accepted books.[27]

The Apocalypse of John is counted as both accepted (Kirsopp. Lake translation: "Recognized") and disputed, which has caused some confusion over what exactly Eusebius meant by doing so. The disputation can perhaps be attributed to Origen.[28] Origen seems to have accepted it in his writings.[29]

Cyril of Jerusalem (348 AD) does not name it among the canonical books (Catechesis IV.33–36).[30]

Athanasius (367 AD) in his Letter 39,[31] Augustine of Hippo (c. 397 AD) in his book On Christian Doctrine (Book II, Chapter 8),[32] Tyrannius Rufinus (c. 400 AD) in his Commentary on the Apostles' Creed,[33] Pope Innocent I (405 AD) in a letter to the bishop of Toulouse[34] and John of Damascus (about 730 AD) in his work An Exposition of the Orthodox Faith (Book IV:7)[35] listed "the Revelation of John the Evangelist" as a canonical book.

Synods

The Council of Laodicea (363) omits it as a canonical book.[36]

The Decretum Gelasianum, which is a work written by an anonymous scholar between 519 and 553, contains a list of books of scripture presented as having been reckoned as canonical by the Council of Rome (382 AD). This list mentions it as a part of the New Testament canon.[37]

The Synod of Hippo (in 393),[38] followed by the Council of Carthage (397), the Council of Carthage (419), the Council of Florence (1442 AD)[39] and the Council of Trent (1546 AD)[40] classified it as a canonical book.[41]

The Apostolic Canons, approved by the Eastern Orthodox Council in Trullo in 692, but rejected by Pope Sergius I, omit it.[42]

Protestant Reformation

Doubts resurfaced during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. Martin Luther called Revelation "neither apostolic nor prophetic" in the 1522 preface to his translation of the New Testament (he revised his position with a much more favorable assessment in 1530), Huldrych Zwingli labelled it "not a book of the Bible", [43] and it was the only New Testament book on which John Calvin did not write a commentary.[44] As of 2015 Revelation remains the only New Testament book not read in the Divine Liturgy of the Eastern Orthodox Church,[45] though Catholic and Protestant liturgies include it.

Texts and manuscripts

There are approximately 300 Greek manuscripts of Revelation.[46] While it is not extant in Codex Vaticanus (4th century), it is extant in the other great uncial codices: Sinaiticus (4th century), Alexandrinus (5th century), and Ephraemi Rescriptus (5th century). In addition, there are numerous papyri, especially 47 and 115 (both 3rd century); minuscules (8th to 10th century); and fragmentary quotations in the Church fathers of the 2nd to 5th centuries and the 6th-century Greek commentary on Revelation by Andreas.[47]

Structure and content

Literary structure

Divisions in the book seem to be marked by the repetition of key phrases, by the arrangement of subject matter into blocks, and associated with its Christological passages,[48] and much use is made of significant numbers, especially the number seven, which represented perfection according to ancient numerology.[49] Nevertheless, there is a "complete lack of consensus" among scholars about the structure of Revelation.[50] The following is therefore an outline of the book's contents rather than of its structure.

Outline

_-_William_Blake.jpg)

- The Revelation of Jesus Christ

- The Revelation of Jesus Christ is communicated to John of Patmos through prophetic visions. (1:1–9)

- John is instructed by the "one like a son of man" to write all that he hears and sees, from the prophetic visions, to Seven churches of Asia. (1:10–13)

- The appearance of the "one like a son of man" is given, and he reveals what the seven stars and seven lampstands represent. (1:14–20)

- Messages for seven churches of Asia

- Ephesus: From this church, those "who overcome are granted to eat from the tree of life, which is in the midst of the Paradise of God." (2:1–7)

- Praised for not bearing those who are evil, testing those who say they are apostles and are not, and finding them to be liars; hating the deeds of the Nicolaitans; having persevered and possessing patience.

- Admonished to "do the first works" and to repent for having left their "first love."

- Smyrna: From this church, those who are faithful until death, will be given "the crown of life." Those who overcome shall not be hurt by the second death. (2:8–11)

- Praised for being "rich" while impoverished and in tribulation.

- Admonished not to fear the "synagogue of Satan", nor fear a ten-day tribulation of being thrown into prison.

- Pergamum: From this church, those who overcome will be given the hidden manna to eat and a white stone with a secret name on it." (2:12–17)

- Praised for holding "fast to My name", not denying "My faith" even in the days of Antipas, "My faithful martyr."

- Admonished to repent for having held the doctrine of Balaam, who taught Balak to put a stumbling block before the children of Israel; eating things sacrificed to idols, committing sexual immorality, and holding the "doctrine of the Nicolaitans."

- Thyatira: From this church, those who overcome until the end, will be given power over the nations in order to dash them to pieces with the rule of a rod of iron; they will also be given the "morning star." (2:18–29)

- Praised for their works, love, service, faith, and patience.

- Admonished to repent for allowing a "prophetess" to promote sexual immorality and to eat things sacrificed to idols.

- Sardis: From this church, those who overcome will be clothed in white garments, and their names will not be blotted out from the Book of Life; their names will also be confessed before the Father and His angels. (3:1–6)

- Admonished to be watchful and to strengthen since their works have not been perfect before God.

- Philadelphia: From this church, those who overcome will be made a pillar in the temple of God having the name of God, the name of the city of God, "New Jerusalem", and the Son of God's new name. (3:7–13)

- Praised for having some strength, keeping "My word", and having not denied "My name."

- Reminded to hold fast what they have, that no one may take their crown.

- Laodicea: From this church, those who overcome will be granted the opportunity to sit with the Son of God on His throne. (3:14–22)

- Admonished to be zealous and repent from being "lukewarm"; they are instructed to buy the "gold refined in the fire", that they may be rich; to buy "white garments", that they may be clothed, so that the shame of their nakedness would not be revealed; to anoint their eyes with eye salve, that they may see.

- Ephesus: From this church, those "who overcome are granted to eat from the tree of life, which is in the midst of the Paradise of God." (2:1–7)

- Before the Throne of God

- The Throne of God appears, surrounded by twenty four thrones with Twenty-four elders seated in them. (4:1–5)

- The four living creatures are introduced. (4:6–11)

- A scroll, with seven seals, is presented and it is declared that the Lion of the tribe of Judah, from the "Root of David", is the only one that will be worthy to open this scroll in the future (5:1–5)[51]

- When the "Lamb having seven horns and seven eyes" took the scroll, the creatures of heaven fell down before the Lamb to give him praise, joined by myriads of angels and the creatures of the earth. (5:6–14)

- Seven Seals are opened

- First Seal: A white horse appears, whose crowned rider has a bow with which to conquer. (6:1–2)

- Second Seal: A red horse appears, whose rider is granted a "great sword" to take peace from the earth. (6:3–4)

- Third Seal: A black horse appears, whose rider has "a pair of balances in his hand", where a voice then says, "A measure of wheat for a penny, and three measures of barley for a penny; and [see] thou hurt not the oil and the wine." (6:5–6)

- Fourth Seal: A pale horse appears, whose rider is Death, and Hades follows him. Death is granted a fourth part of the earth, to kill with sword, with hunger, with death, and with the beasts of the earth. (6:7–8)

- Fifth Seal: "Under the altar", appeared the souls of martyrs for the "word of God", who cry out for vengeance. They are given white robes and told to rest until the martyrdom of their brothers is completed. (6:9–11)

- Sixth Seal: (6:12–17)

- There occurs a great earthquake where "the sun becomes black as sackcloth of hair, and the moon like blood" (6:12).

- The stars of heaven fall to the earth and the sky recedes like a scroll being rolled up (6:13–14).

- Every mountain and island is moved out of place (6:14).

- The people of earth retreat to caves in the mountains (6:15).

- The survivors call upon the mountains and the rocks to fall on them, so as to hide them from the "wrath of the Lamb" (6:16).

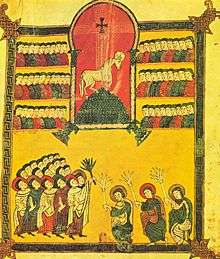

- Interlude: The 144,000 Hebrews are sealed.

- 144,000 from the Twelve Tribes of Israel are sealed as servants of God on their foreheads (7:1–8)

- A great multitude stand before the Throne of God, who come out of the Great Tribulation, clothed with robes made "white in the blood of the Lamb" and having palm branches in their hands. (7:9–17)

- Seventh Seal: Introduces the seven trumpets (8:1–5)

- "Silence in heaven for about half an hour" (8:1).

- Seven angels are each given trumpets (8:2).

- An eighth angel takes a "golden censer", filled with fire from the heavenly altar, and throws it to the earth (8:3–5). What follows are "peals of thunder, rumblings, flashes of lightning, and an earthquake" (8:5).

- After the eighth angel has devastated the earth, the seven angels introduced in verse 2 prepare to sound their trumpets (8:6).

- Seven trumpets are sounded (Seen in Chapters 8, 9, and 12).

- First Trumpet: Hail and fire, mingled with blood, are thrown to the earth burning up a third of the trees and green grass. (8:6–7)

- Second Trumpet: Something that resembles a great mountain, burning with fire, falls from the sky and lands in the ocean. It kills a third of the sea creatures and destroys a third of the ships at sea. (8:8–9)

- Third Trumpet: A great star, named Wormwood, falls from heaven and poisons a third of the rivers and springs of water. (8:10–11)

- Fourth Trumpet: A third of the sun, the moon, and the stars are darkened creating complete darkness for a third of the day and the night. (8:12–13)

- Fifth Trumpet: The First Woe (9:1–12)

- A "star" falls from the sky (9:1).

- This "star" is given "the key to the bottomless pit" (9:1).

- The "star" then opens the bottomless pit. When this happens, "smoke [rises] from [the Abyss] like smoke from a gigantic furnace. The sun and sky [are] darkened by the smoke from the Abyss" (9:2).

- From out of the smoke, locusts who are "given power like that of scorpions of the earth" (9:3), who are commanded not to harm anyone or anything except for people who were not given the "seal of God" on their foreheads (from chapter 7) (9:4).

- The "locusts" are described as having a human appearance (faces and hair) but with lion's teeth, and wearing "breastplates of iron"; the sound of their wings resembles "the thundering of many horses and chariots rushing into battle" (9:7–9).

- Sixth Trumpet: The Second Woe (9:13–21)

- The four angels bound to the great river Euphrates are released to prepare two hundred million horsemen.

- These armies kill a third of mankind by plagues of fire, smoke, and brimstone.

- Interlude: The little scroll. (10:1–11)

- An angel appears, with one foot on the sea and one foot on the land, having an opened little book in his hand.

- Upon the cry of the angel, seven thunders utter mysteries and secrets that are not to be written down by John.

- John is instructed to eat the little scroll that happens to be sweet in his mouth, but bitter in his stomach, and to prophesy.

- John is given a measuring rod to measure the temple of God, the altar, and those who worship there.

- Outside the temple, at the court of the holy city, it is trod by the nations for forty-two months (3 1/2 years).

- Two witnesses prophesy for 1,260 days, clothed in sackcloth. (11:1–14)

- Seventh Trumpet: The Third Woe that leads into the seven bowls (11:15–19)

- The temple of God opens in heaven, where the ark of His covenant can be seen. There are lightnings, noises, thunderings, an earthquake, and great hail.

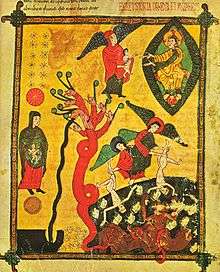

- The Seven Spiritual Figures. (Events leading into the Third Woe)

- A Woman "clothed with a white robe, with the sun at her back, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars" is in pregnancy with a male child. (12:1–2)

- A great Dragon (with seven heads, ten horns, and seven crowns on his heads) drags a third of the stars of Heaven with his tail, and throws them to the Earth. (12:3–4). The Dragon waits for the birth of the child so he can devour it. However, sometime after the child is born, he is caught up to God's throne while the Woman flees into the wilderness into her place prepared of God that they should feed her there for 1,260 days (3½ years). (12:5–6). War breaks out in heaven between Michael and the Dragon, identified as that old Serpent, the Devil, or Satan (12:9). After a great fight, the Dragon and his angels are cast out of Heaven for good, followed by praises of victory for God's kingdom. (12:7–12). The Dragon engages to persecute the Woman, but she is given aid to evade him. Her evasiveness enrages the Dragon, prompting him to wage war against the rest of her offspring, who keep the commandments of God and have the testimony of Jesus Christ. (12:13–17)

- A Beast (with seven heads, ten horns, and ten crowns on his horns and on his heads names of blasphemy) emerges from the Sea, having one mortally wounded head that is then healed. The people of the world wonder and follow the Beast. The Dragon grants him power and authority for forty-two months. (13:1–5)

- The Beast of the Sea blasphemes God's name (along with God's tabernacle and His kingdom and all who dwell in Heaven), wages war against the Saints, and overcomes them. (13:6–10)

- Then, a Beast emerges from the Earth having two horns like a lamb, speaking like a dragon. He directs people to make an image of the Beast of the Sea who was wounded yet lives, breathing life into it, and forcing all people to bear "the mark of the Beast", "666". Events leading into the Third Woe:

- The Lamb stands on Mount Zion with the 144,000 "first fruits" who are redeemed from Earth and victorious over the Beast and his mark and image. (14:1–5)

- The proclamations of three angels. (14:6–13)

- One like the Son of Man reaps the earth. (14:14–16)

- A second angel reaps "the vine of the Earth" and throws it into "the great winepress of the wrath of God... and blood came out of the winepress... up to one thousand six hundred stadia." (14:17–20)

- The temple of the tabernacle, in Heaven, is opened(15:1–5), beginning the "Seven Bowls" revelation.

- Seven angels are given a golden bowl, from the Four Living Creatures, that contains the seven last plagues bearing the wrath of God. (15:6–8)

- Seven bowls are poured onto Earth:

- First Bowl: A "foul and malignant sore" afflicts the followers of the Beast. (16:1–2)

- Second Bowl: The Sea turns to blood and everything within it dies. (16:3)

- Third Bowl: All fresh water turns to blood. (16:4–7)

- Fourth Bowl: The Sun scorches the Earth with intense heat and even burns some people with fire. (16:8–9)

- Fifth Bowl: There is total darkness and great pain in the Beast's kingdom. (16:10–11)

- Sixth Bowl: The Great River Euphrates is dried up and preparations are made for the kings of the East and the final battle at Armageddon between the forces of good and evil. (16:12–16)

- Seventh Bowl: A great earthquake and heavy hailstorm: "every island fled away and the mountains were not found." (16:17–21)

- Aftermath: Vision of John given by "an angel who had the seven bowls"

- The great Harlot who sits on a scarlet Beast (with seven heads and ten horns and names of blasphemy all over its body) and by many waters: Babylon the Great. The angel showing John the vision of the Harlot and the scarlet Beast reveals their identities and fates (17:1–18)

- New Babylon is destroyed. (18:1–8)

- The people of the Earth (the kings, merchants, sailors, etc.) mourn New Babylon's destruction. (18:9–19)

- The permanence of New Babylon's destruction. (18:20–24)

- The Marriage Supper of the Lamb

- A great multitude praises God. (19:1–6)

- The marriage Supper of the Lamb. (19:7–10)

- The Judgment of the two Beasts, the Dragon, and the Dead (19:11–20:15)

- The Beast and the False Prophet are cast into the Lake of Fire. (19:11–21)

- The Dragon is imprisoned in the Bottomless Pit for a thousand years. (20:1–3)

- The resurrected martyrs live and reign with Christ for a thousand years. (20:4–6)

- After the Thousand Years

- The Dragon is released and goes out to deceive the nations in the four corners of the Earth—Gog and Magog—and gathers them for battle at the holy city. The Dragon makes war against the people of God, but is defeated. (20:7–9)

- The Dragon is cast into the Lake of Fire with the Beast and the False Prophet. (20:10)

- The Last Judgment: the wicked, along with Death and Hades, are cast into the Lake of Fire, which is the second death. (20:11–15)

- The New Heaven and Earth, and New Jerusalem

- A "new heaven" and "new earth" replace the old heaven and old earth. There is no more suffering or death. (21:1–8)

- God comes to dwell with humanity in the New Jerusalem. (21:2–8)

- Description of the New Jerusalem. (21:9–27)

- The River of Life and the Tree of Life appear for the healing of the nations and peoples. The curse of sin is ended. (22:1–5)

- Conclusion

- Christ's reassurance that his coming is imminent. Final admonitions. (22:6–21)

Interpretations

| Christian eschatology |

|---|

|

Contrasting beliefs

|

|

The Millennium

|

|

Biblical texts

|

|

Pseudepigrapha

|

|

Key terms

|

| Christianity portal |

Revelation has a wide variety of interpretations, ranging from the simple historical interpretation, to a prophetic view on what will happen in the future by way of the Will of God and the Woman's victory on Satan ("symbolic interpretation"), to different end time scenarios ("futurist interpretation"),[52][53] to the views of critics who deny any spiritual value to Revelation at all,[54] ascribing it to a human-inherited archetype.

Liturgical

Paschal liturgical

This interpretation, which has found expression among both Catholic and Protestant theologians, considers the liturgical worship, particularly the Easter rites, of early Christianity as background and context for understanding the Book of Revelation's structure and significance. This perspective is explained in The Paschal Liturgy and the Apocalypse (new edition, 2004) by Massey H. Shepherd, an Episcopal scholar, and in Scott Hahn's The Lamb's Supper: The Mass as Heaven on Earth (1999), in which he states that Revelation in form is structured after creation, fall, judgment and redemption. Those who hold this view say that the Temple's destruction (AD 70) had a profound effect on the Jewish people, not only in Jerusalem but among the Greek-speaking Jews of the Mediterranean.[55]

They believe the Book of Revelation provides insight into the early Eucharist, saying that it is the new Temple worship in the New Heaven and Earth. The idea of the Eucharist as a foretaste of the heavenly banquet is also explored by British Methodist Geoffrey Wainwright in his book Eucharist and Eschatology (Oxford University Press, 1980). According to Pope Benedict XVI some of the images of Revelation should be understood in the context of the dramatic suffering and persecution of the churches of Asia in the 1st century.

Accordingly, the Book of Revelation should not be read as an enigmatic warning, but as an encouraging vision of Christ's definitive victory over evil.[56]

Oriental Orthodox

In the Coptic Orthodox Church the whole Book of Revelation is read during Apocalypse Night or Good Friday.[57]

Eschatological

Most Christian interpretations fall into one or more of the following categories:

- Historicism, which sees in Revelation a broad view of history;

- Preterism, in which Revelation mostly refers to the events of the apostolic era (1st century) or, at the latest, the fall of the Roman Empire;

- Amillennialism, which rejects a literal interpretation of the "millennium" and treats the content of the book as symbolic;

- Postmillennialism, also rejects a literal interpretation of the "millennium" and sees the world becoming better and better, with the entire world eventually becoming “Christianized;"

- Futurism, which believes that Revelation describes future events (modern believers in this interpretation are often called "millennialists"); and

- Idealism/Allegoricalism, which holds that Revelation does not refer to actual people or events, but is an allegory of the spiritual path and the ongoing struggle between good and evil.

Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy treats the text as simultaneously describing contemporaneous events (events occurring at the same time) and as prophecy of events to come, for which the contemporaneous events were a form of foreshadow. It rejects attempts to determine, before the fact, if the events of Revelation are occurring by mapping them onto present-day events, taking to heart the Scriptural warning against those who proclaim "He is here!" prematurely. Instead, the book is seen as a warning to be spiritually and morally ready for the end times, whenever they may come ("as a thief in the night"), but they will come at the time of God's choosing, not something that can be precipitated nor trivially deduced by mortals.[58] This view is also held by many Catholics, although there is a diversity of opinion about the nature of the Apocalypse within Catholicism.

Book of Revelation is the only book of the New Testament that is not read during services by the Byzantine Rite Churches although in the Western Rite Orthodox Parishes, which are under the same bishops as the Byzantine Rite, it is read.

Protestant

The early Protestants followed a historicist interpretation of the Bible, which identified the Pope as the Antichrist.

Seventh-day Adventist

Similar to the early Protestants, Adventists maintain a historicist interpretation of the Bible's predictions of the apocalypse.[59]

Seventh-day Adventists believe the Book of Revelation is especially relevant to believers in the days preceding the second coming of Jesus Christ. "The universal church is composed of all who truly believe in Christ, but in the last days, a time of widespread apostasy, a remnant has been called out to keep the commandments of God and the faith of Jesus."[60] "Here is the patience of the saints; here are those who keep the commandments of God and the faith of Jesus."[61] As participatory agents in the work of salvation for all humankind, "This remnant announces the arrival of the judgment hour, proclaims salvation through Christ, and heralds the approach of His second advent."[62] The three angels of Revelation 14 represent the people who accept the light of God's messages and go forth as His agents to sound the warning throughout the length and breadth of the earth.[63]

Bahá'í Faith

By the analogous reasoning between the Millerite historicism, and Baha'u'llah's doctrine of progressive revelation, a modified historicist method of interpreting prophecy has become integrated in foremost American Bahá'í teachings.[64]

'Abdu'l-Bahá has given some interpretations about the 11th and 12th chapters of Revelation in Some Answered Questions.[65][66] The 1,260 days spoken of in the forms: one thousand two hundred and sixty days,[67] forty-two months,[68] refers to the 1,260 years in the Islamic Calendar (AH 1260 or 1844 AD). The "two witnesses" spoken of are Muhammad and Ali.[69] Also, the Bible reads, "And there appeared a great wonder in heaven; and behold a great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns, and seven crowns upon his heads".[70] The seven heads of the dragon are symbolic of the seven provinces dominated by the Umayyads: Damascus, Persia, Arabia, Egypt, Africa, Andalusia, and Transoxania. The ten horns represent the ten names of the leaders of the Umayyad dynasty: Abu Sufyan, Muawiya, Yazid, Marwan, Abd al-Malik, Walid, Sulayman, Umar, Hisham, and Ibrahim. Some names were re-used, as in the case of Yazid II and Yazid III and the like, which were not counted for this interpretation.[71]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Book of Mormon states that John the Apostle is the author of Revelation and that he was foreordained by God to write it.[72]

Doctrine and Covenants, section 77, postulates answers to specific questions regarding the symbolism contained in the Book of Revelation.[73] Topics include: the sea of glass, the four beasts and their appearance, the 24 elders, the book with seven seals, certain angels, the sealing of the 144,000, the little book eaten by John, and the two witnesses in Chapter 11.

Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints believe that the warning contained in Revelation 22:18–19[74] does not refer to the biblical canon as a whole.[75] Rather, an open and ongoing dialogue between God and the modern-day Prophet and Apostles of the LDS faith constitute an open canon of scripture.[73][76]

Esoteric

Christian Gnostics, however, are unlikely to be attracted to the teaching of Revelation because the doctrine of salvation through the sacrificed Lamb, which is central to Revelation, is repugnant to Gnostics. Christian Gnostics "believed in the Forgiveness of Sins, but in no vicarious sacrifice for sin ... they accepted Christ in the full realisation of the word; his life, not his death, was the keynote of their doctrine and their practice."[77]

James Morgan Pryse was an esoteric gnostic who saw Revelation as a western version of the Hindu theory of the Chakra. He began his work, "The purpose of this book is to show that the Apocalypse is a manual of spiritual development and not, as conventionally interpreted, a cryptic history or prophecy."[78] Such diverse theories have failed to command widespread acceptance. But Christopher Rowland argues: "there are always going to be loose threads which refuse to be woven into the fabric as a whole. The presence of the threads which stubbornly refuse to be incorporated into the neat tapestry of our world-view does not usually totally undermine that view."[79]

Radical discipleship

The radical discipleship interpretation asserts that the Book of Revelation is best understood as a handbook for radical discipleship; i. e., how to remain faithful to the spirit and teachings of Jesus and avoid simply assimilating to surrounding society. In this interpretation the primary agenda of the book is to expose as impostors the worldly powers that seek to oppose the ways of God and God's Kingdom. The chief temptation for Christians in the 1st century, and today, is to fail to hold fast to the non-violent teachings and example of Jesus and instead be lured into unquestioning adoption and assimilation of worldly, national or cultural values – imperialism, nationalism, and civil religion being the most dangerous and insidious.

This perspective (closely related to liberation theology) draws on the approach of Bible scholars such as Ched Myers, William Stringfellow, Richard Horsley, Daniel Berrigan, Wes Howard-Brook,[80] and Joerg Rieger.[81] Various Christian anarchists, such as Jacques Ellul, have identified the State and political power as the Beast[82] and the events described, being their doings and results, the aforementioned 'wrath'.

Aesthetic and literary

Literary writers and theorists have contributed to a wide range of theories about the origins and purpose of the Book of Revelation. Some of these writers have no connection with established Christian faiths but, nevertheless, found in Revelation a source of inspiration. Revelation has been approached from Hindu philosophy and Jewish Midrash. Others have pointed to aspects of composition which have been ignored such as the similarities of prophetic inspiration to modern poetic inspiration, or the parallels with Greek drama. In recent years, theories have arisen which concentrate upon how readers and texts interact to create meaning and which are less interested in what the original author intended.

Charles Cutler Torrey taught Semitic languages at Yale University. His lasting contribution has been to show how prophets, such as the scribe of Revelation, are much more meaningful when treated as poets first and foremost. He thought this was a point often lost sight of because most English bibles render everything in prose.[83] Poetry was also the reason John never directly quoted the older prophets. Had he done so, he would have had to use their (Hebrew) poetry whereas he wanted to write his own. Torrey insisted Revelation had originally been written in Aramaic.[84]

This was why the surviving Greek translation was written in such a strange idiom. It was a literal translation that had to comply with the warning at Revelation 22:18 that the text must not be corrupted in any way. According to Torrey, the story is that "The Fourth Gospel was brought to Ephesus by a Christian fugitive from Palestine soon after the middle of the first century. It was written in Aramaic." Later, the Ephesians claimed this fugitive had actually been the beloved disciple himself. Subsequently, this John was banished by Nero and died on Patmos after writing Revelation. Torrey argued that until AD 80, when Christians were expelled from the synagogues,[85] the Christian message was always first heard in the synagogue and, for cultural reasons, the evangelist would have spoken in Aramaic, else "he would have had no hearing."[86] Torrey showed how the three major songs in Revelation (the new song, the song of Moses and the Lamb and the chorus at 19: 6–8) each fall naturally into four regular metrical lines plus a coda.[87] Other dramatic moments in Revelation, such as 6:16 where the terrified people cry out to be hidden, behave in a similar way.[88]

Christina Rossetti was a Victorian poet who believed the sensual excitement of the natural world found its meaningful purpose in death and in God.[89] Her The Face of the Deep is a meditation upon the Apocalypse. In her view, what Revelation has to teach is patience.[90] Patience is the closest to perfection the human condition allows.[91] Her book, which is largely written in prose, frequently breaks into poetry or jubilation, much like Revelation itself. The relevance of John's visions[92] belongs to Christians of all times as a continuous present meditation. Such matters are eternal and outside of normal human reckoning. "That winter which will be the death of Time has no promise of termination. Winter that returns not to spring ... – who can bear it?"[93] She dealt deftly with the vengeful aspects of John's message. "A few are charged to do judgment; everyone without exception is charged to show mercy."[94] Her conclusion is that Christians should see John as "representative of all his brethren" so they should "hope as he hoped, love as he loved."[95]

Recently, aesthetic and literary modes of interpretation have developed, which focus on Revelation as a work of art and imagination, viewing the imagery as symbolic depictions of timeless truths and the victory of good over evil. Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza wrote Revelation: Vision of a Just World from the viewpoint of rhetoric.[96] Accordingly, Revelation's meaning is partially determined by the way John goes about saying things, partially by the context in which readers receive the message and partially by its appeal to something beyond logic.[97]

Professor Schüssler Fiorenza believes that Revelation has particular relevance today as a liberating message to disadvantaged groups. John's book is a vision of a just world, not a vengeful threat of world-destruction. Her view that Revelation's message is not gender-based has caused dissent. She says we are to look behind the symbols rather than make a fetish out of them. In contrast, Tina Pippin states that John writes "horror literature" and "the misogyny which underlies the narrative is extreme."[97]

D. H. Lawrence took an opposing, pessimistic view of Revelation in the final book he wrote, Apocalypse.[98] He saw the language which Revelation used as being bleak and destructive; a 'death-product'. Instead, he wanted to champion a public-spirited individualism (which he identified with the historical Jesus supplemented by an ill-defined cosmic consciousness) against its two natural enemies. One of these he called "the sovereignty of the intellect"[99] which he saw in a technology-based totalitarian society. The other enemy he styled "vulgarity"[100] and that was what he found in Revelation. "It is very nice if you are poor and not humble ... to bring your enemies down to utter destruction, while you yourself rise up to grandeur. And nowhere does this happen so splendiferously than in Revelation."[101]

His specific aesthetic objections to Revelation were that its imagery was unnatural and that phrases like "the wrath of the Lamb" were "ridiculous." He saw Revelation as comprising two discordant halves. In the first, there was a scheme of cosmic renewal in "great Chaldean sky-spaces", which he quite liked. After that, Lawrence thought, the book became preoccupied with the birth of the baby messiah and "flamboyant hate and simple lust ... for the end of the world." Lawrence coined the term "Patmossers" to describe those Christians who could only be happy in paradise if they knew their enemies were suffering in hell.[102]

Academic

Modern biblical scholarship attempts to understand Revelation in its 1st-century historical context within the genre of Jewish and Christian apocalyptic literature.[103] This approach considers the text as an address to seven historical communities in Asia Minor. Under this interpretation, assertions that "the time is near" are to be taken literally by those communities. Consequently, the work is viewed as a warning to not conform to contemporary Greco-Roman society which John "unveils" as beastly, demonic, and subject to divine judgment.[103]

New Testament narrative criticism also places Revelation in its first century historical context but approaches the book from a literary perspective.[104] For example, narrative critics examine characters and characterization, literary devices, settings, plot, themes, point of view, implied reader, implied author, and other constitutive features of narratives in their analysis of the book.

Although the acceptance of Revelation into the canon has, from the beginning, been controversial, it has been essentially similar to the career of other texts.[105] The eventual exclusion of other contemporary apocalyptic literature from the canon may throw light on the unfolding historical processes of what was officially considered orthodox, what was heterodox, and what was even heretical.[105] Interpretation of meanings and imagery are anchored in what the historical author intended and what his contemporary audience inferred; a message to Christians not to assimilate into the Roman imperial culture was John's central message.[103] Thus, his letter (written in the apocalyptic genre) is pastoral in nature (its purpose is offering hope to the downtrodden),[106] and the symbolism of Revelation is to be understood entirely within its historical, literary, and social context.[106] Critics study the conventions of apocalyptic literature and events of the 1st century to make sense of what the author may have intended.[106]

Scholar Barbara Whitlock pointed out a similarity between the consistent destruction of thirds depicted in the Book of Revelation (a third of mankind by plagues of fire, smoke, and brimstone, a third of the trees and green grass, a third of the sea creatures and a third of the ships at sea, etc.) and the Iranian mythology evil character Zahhak or Dahāg, depicted in the Avesta, the earliest religious texts of Zoroastrianism. Dahāg is mentioned as wreaking much evil in the world until at last chained up and imprisoned on the mythical Mt. Damāvand. The Middle Persian sources prophesy that at the end of the world, Dahāg will at last burst his bonds and ravage the world, consuming one in three humans and livestock, until the ancient hero Kirsāsp returns to life to kill Dahāg. Whitlock wrote: "Zoroastrianism, the state religion of the Roman Empire's main rival, was part of the intellectual millieu in which Christianity came into being, just as were Judaism, the Greek-Roman religion, and the worship of Isis and Mithras. A Zoroastrian influence is completely plausible".[107]

Old Testament origins

Much of Revelation employs ancient sources, primarily but not exclusively from the Old Testament. For example, Howard-Brook and Gwyther[108] regard the Book of Enoch (1 Enoch) as an equally significant but contextually different source. "Enoch's journey has no close parallel in the Hebrew scriptures." Revelation, in one section, forms an inverted parallel (chiasmus) with the book of Enoch in which 1 En 100:1–3 has a river of blood deep enough to submerge a chariot and in Rev 14:20 has a river of blood up to the horse's bridle. There is an angel ascending in both accounts (1 En 100:4; Rev 14:14–19) and both accounts have three messages (1 En 100:7–9; Rev 14:6–12).[109]

Academics showed little interest in this topic until recently.[110] This was not, however, the case with popular writers from non-conforming backgrounds, who interspersed the text of Revelation with the prophecy they thought was being promised. For example, an anonymous Scottish commentary of 1871[111] prefaces Revelation 4 with the Little Apocalypse of Mark 13, places Malachi 4:5 ("Behold I will send you Elijah the prophet before the coming of the great and dreadful day of the Lord") within Revelation 11 and writes Revelation 12:7 side by side with the role of "the Satan" in the Book of Job. The message is that everything in Revelation will happen in its previously appointed time.

Steve Moyise uses the index of the United Bible Societies' Greek New Testament to show that "Revelation contains more Old Testament allusions than any other New Testament book, but it does not record a single quotation."[112] Perhaps significantly, Revelation chooses different sources than other New Testament books. Revelation concentrates on Isaiah, Psalms, and Ezekiel, while neglecting, comparatively speaking, the books of the Pentateuch that are the dominant sources for other New Testament writers. Methodological objections have been made to this course as each allusion may not have an equal significance. To counter this, G. K. Beale sought to develop a system that distinguished 'clear', 'probable', and 'possible' allusions. A clear allusion is one with almost the same wording as its source, the same general meaning, and which could not reasonably have been drawn from elsewhere. A probable allusion contains an idea which is uniquely traceable to its source. Possible allusions are described as mere echoes of their putative sources.

Yet, with Revelation, the problems might be judged more fundamental. The author seems to be using his sources in a completely different way to the originals. For example, he borrows the 'new temple' imagery of Ezekiel 40–48 but uses it to describe a New Jerusalem which, quite pointedly, no longer needs a temple because it is God's dwelling. Ian Boxall[113] writes that Revelation "is no montage of biblical quotations (that is not John's way) but a wealth of allusions and evocations rewoven into something new and creative." In trying to identify this "something new", Boxall argues that Ezekiel provides the 'backbone' for Revelation. He sets out a comparative table listing the chapters of Revelation in sequence and linking most of them to the structurally corresponding chapter in Ezekiel. The interesting point is that the order is not the same. John, on this theory, rearranges Ezekiel to suit his own purposes.

Some commentators argue that it is these purposes – and not the structure – that really matter. G. K. Beale believes that, however much John makes use of Ezekiel, his ultimate purpose is to present Revelation as a fulfillment of Daniel 7.[114] Richard Bauckham has argued that John presents an early view of the Trinity through his descriptions of the visions and his identifying Jesus and the Holy Spirit with YHWH.[115] Brandon Smith has expanded on both of their proposals while proposing a "trinitarian reading" of Revelation, arguing that John uses Old Testament language and allusions from various sources to describe a multiplicity of persons in YHWH without sacrificing monotheism, which would later be codified in the trinitarian doctrine of Nicene Christianity.[116]

One theory, Revelation Draft Hypothesis, sees the book of Revelation constructed by forming parallels with several texts in the Old Testament such as Ezekiel, Isaiah, Zechariah, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Exodus, and Daniel. For example, Ezekiel's encounter with God is in reverse order as John's encounter with God (Ezek 1:5–28; Rev 4:2–7) note both accounts have beings with faces of a lion, ox or calf, man, and eagle (Ezek 1:10; Rev 4:7), both accounts have an expanse before the throne (Ezek 1:22; Rev 4:6). The chariot's horses in Zechariah's are the same colors as the four horses in Revelation (Zech 6:1–8; Rev 6:1–8). The nesting of the seven marches around Jericho by Joshua is reenacted by Jesus nesting the seven trumpets within the seventh seal (Josh 6:8–10; Rev 6:1–17; 8:1–9:21; 11:15–19). The description of the beast in Revelation is taken directly out of Daniel (see Dan 7:2–8; Rev 13:1–7). The method that John used allowed him to use the Hebrew Scriptures as the source and also use basic techniques of parallel formation, thereby alluding to the Hebrew Scriptures.[109][117]

Figures in Revelation

In order of appearance:

- John of Patmos

- The angel who reveals the Revelation of Jesus Christ

- The One who sits on the Throne

- Twenty-four crowned elders

- Four living creatures

- The Lion of Judah who is the seven horned Lamb with seven eyes

- Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

- the souls of those who had been slain for the word of God, each given a white robe

- Four angels holding the four winds of the Earth

- The seal-bearer angel (144,000 of Israel sealed)

- A great multitude from every nation

- Seven angelic trumpeters

- The star called Wormwood

- Angel of Woe

- Scorpion-tailed Locusts

- Abaddon

- Four angels bound to the great river Euphrates

- Two hundred million lion-headed cavalry

- The mighty angel of Seven thunders

- The Two witnesses

- Beast of the Sea having seven heads and ten horns

- The woman and her child

- The Dragon, fiery red with seven heads

- Saint Michael the Archangel

- Lamb-horned Beast of the Earth

- Image of the Beast of the sea

- Messages of the three angels

- The angelic reapers and the grapes of wrath

- Seven plague angels

- Seven bowls of wrath

- The False Prophet

- Whore of Babylon

- The rider on a white horse

- The first resurrection and the thousand years

- Gog and Magog

- Death and Hades

See also

- Alpha and Omega

- The Apocalypse – 2000 film

- Apocalypse of John – dated astronomically

- Apocalypse of Peter

- Apocalypse of Zerubbabel

- Apocalypticism

- Arethas of Caesarea

- Biblical cosmology

- Biblical numerology

- Book of Ezekiel

- Christian eschatological differences

- Day-year principle

- English Apocalypse manuscripts

- Horae Apocalypticae

- Maccabees

- Masada

- The New Earth

- Number of the Beast

- Patmos

- Textual variants in the Book of Revelation

- Vespasian

- Woman of the Apocalypse

Notes

- Other apocalypses popular in the early Christian era did not achieve canonical status, except 2 Esdras (also known as the Apocalypse of Ezra), which is recognized as canonical in Ethiopian Orthodox churches.

- However, among recent writers, John Behr[5] argues that Irenaeus and the earliest traditions of the church placed the writing in the reign of Nero.

References

- Carson, Don (2005). An Introduction to the New Testament (2nd ed.). Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan. pp. 465ff. ISBN 978-0-310-51940-9.

- Collins 1984, p. 28.

- Bauckham 1993, p. 2.

- Stuckenbruck 2003, pp. 1535–1536.

- Behr, John (2019). John the Theologian and his Paschal Gospel. Oxford.

- Stuckenbruck 2003, p. 1536.

- Collins 1984, pp. 28–29.

- Collins 1984, pp. 26–27.

- Bauckham 1993, p. 2, 24–25.

- Stuckenbruck 2003, p. 1535.

- Cross & Livingstone 2005.

- Perkins 2012, p. 19ff.

- Collins 1982, p. 100.

- McKim 2014, p. 16.

- Couch 2001, p. 81.

- Fekkes, Jan (1994). Isaiah and Prophetic Traditions in the Book of Revelation: Visionary Antecedents and their Development (The Library of New Testament Studies). Bloomsbury T&T Clark. pp. 61–63. ISBN 978-1-85075-456-5.

- Beale & McDonough 2007, pp. 1081–1084.

- Stephens 2011, pp. 143–145.

- Stephens 2011, p. 152.

- Collins 1984, p. 154.

- Wall 2011, p. no page number.

-

Taylor, David G. K. (11 September 2002). "Christian regional diversity". In Esler, Philip F. (ed.). The Early Christian World. Routledge Worlds. Routledge (published 2002). p. 338. ISBN 978-1-134-54919-1. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

[...] the minor Catholic epistles and Revelation continued to be omitted, and are still not included in the canon of the church of the East which was geographically (and from the late-fifth century doctrinally) isolated in the Persian empire.

- Pattemore 2004, p. 1.

- Stonehouse n.d., pp. 138–142.

- Eugenia Scarvelis Constantinou (editor) Commentary on the Apocalypse by Andrew of Caesarea (CUA Press 2011 ISBN 978-0-8132-0123-8), pp. 3–6

- of Caesarea, Eusebius. Church History, Book VII Chapter 25. newadvent. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- of Caesarea, Eusebius. Church History, Book III Chapter 25. newadvent. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- Kalin, ER (1990), "Re-examining New Testament Canon History: 1. The Canon of Origen", Currents in Theology and Mission, 17: 274–82

- Origen. Church Fathers: Commentary on John, Book V: 3 (Origen). Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- of Jerusalem, Cyril. Catechetical Lecture 4 Chapter 35. newadvent. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- of Alexandria, Athanasius. Church Fathers: Letter 39 (Athanasius). newadvent. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- of Hippo, Augustine. On Christian Doctrine Book II Chapter 8:2. newadvent. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- of Aquileia, Rufinus. Commentary on the Apostles' Creed #37. newadvent. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- "Letter of Innocent I on the Canon of Scripture". www.bible-researcher.com.

- of Damascus, John. An Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, Book IV Chapter 17. newadvent. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- of Laodicea, Synod. Synod of Laodicea Canon 60. newadvent. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- Pearse, Roger. "Tertullian : Decretum Gelasianum (English translation)". www.tertullian.org.

- "Canon XXIV. (Greek xxvii.)", The Canons of the 217 Blessed Fathers who assembled at Carthage, Christian Classics Ethereal Library

- "Eccumenical Council of Florence and Council of Basel". www.ewtn.com.

- "Paul III Council of Trent-4". www.ewtn.com.

- "Church Fathers: Council of Carthage (A.D. 419)". www.newadvent.org.

- in Trullo, Council. The Apostolic Canons. Canon 85. newadvent. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

-

Glasson, T.F. (1965). "How was the Book received by the Church?". In Glasson, T.F. (ed.). The Revelation of John. Cambridge Bible Commentaries on the New Testament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 6. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

Zwingli, the Swiss Reformer, said, '[The Book of Revelation] is not a book of the Bible'.

- Hoekema 1979, p. 297.

-

Boring, M. Eugene (1989). Revelation. Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press (published 2011). p. 3. ISBN 9780664236281. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

To this day, Catholic and Protestant lectionaries have only minimal readings from Revelation, and the Greek Orthodox lectionary omits it altogether.

- Aune, David (1997). Word Biblical Commentary 52A: Revelation 1–5. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan. p. cxxxviii. ISBN 978-0-310-52177-8.

- Pate 2010, p. no page number.

- Tenney 1988, pp. 32–41.

- Senior & Getty 1990, pp. 398–399.

- Mounce 1998, p. 32.

- "Introduction to the Book". pierre2.net. 3 January 2011. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- Robert J. Karris (ed.) The Collegeville Bible Commentary Liturgical Press, 1992 p. 1296.

- Ken Bowers, Hiding in plain sight, Cedar Fort, 2000 p. 175.

- Carl Gustav Jung in his autobiography Memories Dream Reflections said "I will not discuss the transparent prophecies of the Book of Revelation because no one believes in them and the whole subject is felt to be an embarrassing one."

- Scott Hahn, The Lamb's Supper: The Mass as Heaven on Earth, ISBN 0-385-49659-1. New York: Doubleday, 1999.

- Catholic Online (23 August 2006). "Pope Benedict: Read Book of Revelation as Christ's victory over evil – International – Catholic Online". Catholic.org. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- "Night of the Apocalypse", published by Coptic Orthodox Diocese of the Southern United States, accessed 23 May 2018

- Averky (Taushev), Archbishop (1996). Eng. tr. Fr. Seraphim Rose (ed.). The Apocalypse: In the Teachings of Ancient Christianity. Platina, California: St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood. ISBN 978-0-938635-67-3.

- Holbrook, Frank (July 1983). "What prophecy means to this church". Ministry, International Journal for Pastors. 56 (7): 21. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- "Seventh-day Adventist 28 Fundamental Beliefs" (PDF). The Official Site of the Seventh-day Adventist World Church. General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- "Revelation 14:12". Biblia.com. Logos Research Systems. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- "The Remnant and its Mission". The Official Site of the Seventh-day Adventist World Church. General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- "Councils to the Church". Ellen G. White Writings. White Estate. p. 58. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- "The Final Consummation: American Bahá'ís, Millerites and Biblical Time Prophecy". Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- 'Abdu'l-Baha, Abbas Effendi. "Some Answered Questions". bahai.org. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- 'Abdu'l-Baha, Abbas Effendi. "Some Answered Questions". bahai.org. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- "Holy Bible". biblegateway.com. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- "Holy Bible". biblegateway.com. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- "Bahá'í Reference Library – Some Answered Questions, pp. 45–61".

- "Holy Bible". biblegateway.com. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- 'Abdu'l-Baha, Abbas Effendi. "Some Answered Questions". bahai.org. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- "1 Nephi 14:18–27".

- "Doctrine and Covenants 20:35".

- "Revelation 22:18–19".

- Hunter, Howard W. "No Man Shall Add to or Take Away".

- "Articles of Faith 1:9".

- R. Frances Swiney (Rosa Frances Emily Biggs) The Esoteric Teaching of the Gnostics London: Yellon, Williams & Co (1909) pp. 3, 4

- James M. Pryse Apocalypse Unsealed London: Watkins (1910). The theory behind the book is given in Arthur Avalon (Sir John Woodroffe) The Serpent Power Madras (Chennai): Ganesh & Co (1913). One version of how these beliefs might have travelled from India to the Middle East, Greece and Rome is given in the opening chapters of Rudolf Otto The Kingdom of God and the Son of Man London: Lutterworth (1938)

- Christopher Rowland Revelation London: Epworth (1993) p. 5

- Howard-Brook, Wes; Gwyther, Anthony (1999). Unveiling Empire: Reading Revelation Then and Now. Orbis Books. ISBN 978-1-57075-287-2.

- Rieger, Joerg (2007). Christ & Empire: From Paul to Postcolonial Times. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-2038-7.

- Christoyannopoulos, Alexandre (2010). Christian Anarchism: A Political Commentary on the Gospel. Exeter: Imprint Academic. pp. 123–126.

Revelation

- Charles C. Torrey The Apocalypse of John New Haven: Yale University Press (1958). Christopher R. North in his The Second Isaiah London: OUP (1964) p. 23 says of Torrey's earlier Isaiah theory, "Few scholars of any standing have accepted his theory." This is the general view of Torrey's theories. However, Christopher North goes on to cite Torrey on 20 major occasions and many more minor ones in the course of his book. So, Torrey must have had some influence and poetry is the key.

- Apocalypse of John p. 7

- Apocalypse of John p. 37

- Apocalypse of John p. 8

- Apocalypse of John p. 137

- Apocalypse of John p. 140

- "Flowers preach to us if we will hear", begins her poem 'Consider the lilies of the field' Goblin Market London: Oxford University Press (1913) p. 87

- Ms Rossetti remarks that patience is a word which does not occur in the Bible until the New Testament, as if the usage first came from Christ's own lips. Christina Rossetti The Face of the Deep London: SPCK (1892) p. 115

- "Christians should resemble fire-flies, not glow-worms; their brightness drawing eyes upward, not downward." The Face of the Deep p. 26

- 'vision' lends the wrong emphasis as Ms Rossetti sought to minimise the distinction between John's experience and that of others. She quoted 1 John 3:24 "He abideth in us, by the Spirit which he hath given us" to show that when John says, "I was in the Spirit" it is not exceptional.

- The Face of the Deep p. 301

- The Face of the Deep p. 292

- The Face of the Deep p. 495

- Elisabeth Schuessler Fiorenza Revelation: Vision of a Just World Edinburgh: T&T Clark (1993). The book seems to have started life as Invitation to the Book of Revelation Garden City: Doubleday (1981)

- Tina Pippin Death & Desire: The rhetoric of gender in the Apocalypse of John Louisville: Westminster-John Knox (1993) p. 105

- D H Lawrence Apocalypse London: Martin Secker (1932) published posthumously with an introduction (pp. v–xli) by Richard Aldington which is an integral part of the text.

- Apocalypse p. xxiii

- Apocalypse p. 6

- Apocalypse p. 11 Lawrence did not consider how these two types of Christianity (good and bad in his view) might be related other than as opposites. He noted the difference meant that the John who wrote a gospel could not be the same John that wrote Revelation.

- D. H. Lawrence (1995). Apocalypse and the Writings on Revelation. Penguin Books. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-14-018781-6.

- Dale Martin 2009 (lecture). "24. Apocalyptic and Accommodation" on YouTube. Yale University. Accessed 22 July 2013. Lecture 24 (transcript)

- David L. Barr, Tales of the End: A Narrative Commentary on the Book of Revelation (Santa Rosa: Polebridge Press, 1998); Barr, "Narrative Technique in the Book of Revelation". In Oxford Handbook of Biblical Narrative, ed. Danna Nolan Fewell (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 376–88; James L. Resseguie, Revelation Unsealed: A Narrative Critical Approach to John’s Apocalypse, Biblical Interpretation Series 32 (Leiden: Brill, 1998); Resseguie, The Revelation of John: A Narrative Commentary (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2009).

- "Lecture 2: From Stories to Canon". CosmoLearning Religious Studies.

- Bart D. Ehrman (9 June 2016). "Bart Ehrman Discusses the Apocalypticist" – via YouTube.

- Dr. Barbara Whitlock, "Tracing out the convoluted sources of Christianity" in George D. Barnes (ed.), "Collected New Essays in Comparative Religion"

- Wes Howard-Brook & Anthony Gwyther Unveiling Empire New York: Orbis (1999) p. 76

- Lewis, Kim (2015). How John Wrote the Book of Revelation: From Concept to Publication. Lorton, Virginia: Kim Mark Lewis. pp. 216, 226. ISBN 978-1-943325-00-9.

- S Moyise p. 13 reports no work whatsoever done between 1912 and 1984

- Anon An exposition of the Apocalypse on a new principle of literal interpretation Aberdeen: Brown (1871)

- S. Moyise The Old Testament in the Book of Revelation Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press (1995) p. 31

- Ian Boxall The Revelation of St John London: Continuum & Peabody MA: Hendrickson (2006) p. 254

- G. K. Beale John's use of the Old Testament in Revelation Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press (1998) p. 109

- Bauckham 1993.

- Brandon D. Smith, "The Identification of Jesus with YHWH in the Book of Revelation, Criswell Theological Review (2016)

- "Revelation Draft Hypothesis".

Bibliography

- Ammannati, Renato (2010). Rivelazione e Storia. Ermeneutica dell'Apocalisse. Transeuropa.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barr, David, L. (1998). Tales of the End: A Narrative Commentary on the Book of Revelation. Santa Rosa, CA: Polebridge Press, ISBN 978-1598150339.

- Bass, Ralph E., Jr. (2004). Back to the Future: A Study in the Book of Revelation, Greenville, South Carolina: Living Hope Press, ISBN 0-9759547-0-9.

- Bauckham, Richard (1993). The Theology of the Book of Revelation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-35691-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beale, G.K.; McDonough, Sean M. (2007). "Revelation". In Beale, G. K.; Carson, D. A. (eds.). Commentary on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament. Baker Academic. ISBN 978-0-8010-2693-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beale G.K. (1999). The Book of Revelation, NIGTC, Grand Rapids: Cambridge. ISBN 0-8028-2174-X

- Bousset W., Die Offenbarung Johannis, Göttingen 18965, 19066.

- Boxall, Ian, (2006). The Revelation of Saint John (Black's New Testament Commentary) London: Continuum, and Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson. ISBN 0-8264-7135-8 U.S. edition: ISBN 1-56563-202-8

- Boxall, Ian (2002). Revelation: Vision and Insight – An Introduction to the Apocalypse, London: SPCK ISBN 0-281-05362-6

- Brown, Raymond E. (1997). Introduction to the New Testament. Anchor Bible. ISBN 978-0-385-24767-2.

- Burkett, Delbert (2000). An Introduction to the New Testament and the Origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00720-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collins, Adela Yarbro (1984). Crisis and Catharsis: The Power of the Apocalypse. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-24521-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Couch, Mal, ed. (2001). A Bible Handbook to Revelation. Kregel Academic. ISBN 978-0-8254-9393-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (2005). "Revelation, Book of". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3 rev. ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780192802903.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crutchfield, Larry V. (2001). "Revelation in the New Testament Canon". In Couch, Mal (ed.). A Bible Handbook to Revelation. Kregel Academic. ISBN 978-0-8254-9393-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2004). The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. New York: Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-515462-7.

- Ford, J. Massyngberde (1975). Revelation, The Anchor Bible, New York: Doubleday ISBN 0-385-00895-3.

- Gentry, Kenneth L., Jr. (1998). Before Jerusalem Fell: Dating the Book of Revelation, Powder Springs, GA: American Vision, ISBN 0-915815-43-5.

- Gentry, Kenneth L., Jr. (2002). The Beast of Revelation, Powder Springs, GA: American Vision, ISBN 0-915815-41-9.

- Hahn, Scott (1999). The Lamb's Supper: Mass as Heaven on Earth, Darton, Longman, Todd, ISBN 0-8146-5818-0

- Harrington Wilfrid J. (1993). Sacra Pagina: Revelation, Michael Glazier, ISBN 978-0-8146-5818-5

- Hernández, Juan (2006). Scribal habits and theological influences in the Apocalypse, Tübingen

- Hoekema, Anthony A. (1979). The Bible and the future. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3516-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hudson, Gary W. (2006). Revelation: Awakening The Christ Within, Vesica Press, ISBN 0-9778517-2-9

- Jennings, Charles A. (2001). The Book of Revelation From An Israelite and Historicist Interpretation, Truth in History Publications. ISBN 978-0-9792565-8-5.

- Kiddle M. (1941). The Revelation of St. John (The Moffat New Testament Commentary), New York – London

- Kirsch, Thomas (2006). A History of the End of the World: How the Most Controversial Book in the Bible Changed the Course of Western Civilization. New York: HarperOne

- Lohmeyer, Ernst (1953). Die Offenbarung des Johannes, Tübingen

- Muggleton, Lodowicke (2010). Works on the Book of Revelation London ISBN 978-1-907466-04-5

- Müller, U.B. (1995). Die Offenbarung des Johannes, Güttersloh

- McDonald, Lee Martin; Sanders, James A. (2002). The Canon Debate. Hendrickson Publishers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKim, Donald K. (2014). The Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms, Second Edition. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-23835-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mounce, Robert H. (1998). The Book of Revelation. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2537-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pate, C. Marvin (2010). Four Views on the Book of Revelation. Zondervan.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pagels, Elaine (2012). Revelations: Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation, Viking Adult, ISBN 0-670-02334-5 Prigent P., L'Apocalypse, Paris 1981.

- Weor, Samael Aun (2004) [1960]. The Aquarian Message: Gnostic Kabbalah and Tarot in the Apocalypse of St. John. Thelema Press. ISBN 978-0-9745916-5-0.

- Pattemore, Stephen (2004). The People of God in the Apocalypse. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-4412-3655-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Resseguie, James L. (2009) The Revelation of John: A Narrative Commentary. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic. ISBN 978-0801032134.

- Perkins, Pheme (2012). Reading the New Testament: An Introduction. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-4786-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roloff J. (1987). Die Offenbarung des Johannes

- Senior, Donald; Getty, Mary Ann (1990). The Catholic Study Bible. Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shepherd, Massey H. (2004). The Paschal Liturgy and the Apocalypse, James Clarke, ISBN 0-227-17005-9

- Schnelle, Udo (2007). Theology of the New Testament [tr.2009]. Baker Academic. ISBN 978-0-8010-3604-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stonehouse, Ned B. (n.d.) [c. 1929]. The Apocalypse in the Ancient Church. A Study in the History of the New Testament Canon. Goes: Oosterbaan & Le Cointre[Major discussion of the controversy surrounding the acceptance/rejection of Revelation into the New Testament canon.]CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stuckenbruck, Loren T. (2003). "Revelation". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William (eds.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. p. 1535. ISBN 978-0-8028-3711-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stephens, Mark B. (2011). Annihilation or Renewal?: The Meaning and Function of New Creation in the Book of Revelation. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-150838-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sweet, J. P. M. (1979, Updated 1990). Revelation, London: SCM Press, and Philadelphia: Trinity Press International. ISBN 0-334-02311-4.

- Tenney, Merrill C. (1988). Interpreting Revelation. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-0421-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vitali, Francesco (2008). Piccolo Dizionario dell'Apocalisse, TAU Editrice, Todi

- Wall, Robert W. (2011). Revelation. Baker Books. ISBN 978-1-4412-3655-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wikenhauser A., Offenbarung des Johannes, Regensburg 1947, 1959.

- Witherington III, Ben (2003). Revelation, The New Cambridge Bible Commentary, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-00068-0.

- Zahn Th., Die Offenbarung des Johannes, t. 1–2, Leipzig 1924–1926.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Book of Revelation. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Book of Revelation |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Early Christian Writings: Apocalypse of John: text, introduction, context

- "Revelation to John." Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Apocalypse, Book of – Article from the Catholic Encyclopedia

- Understanding the Book of Revelation – Article by L. Michael White from PBS Frontline program "Apocalypse!"

- The Marvelous Address: The Revelation of the Beloved (Disciple) is an 18th-century manuscript about the book of Revelation in Arabic

- Jewish Encyclopedia

- Biesen, C. van den (1913). "Apocalypse". Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Schem, A. J. (1879). . The American Cyclopædia.

- The Apocalypse, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Martin Palmer, Marina Benjamin & Justin Champion (In Our Time, 17 July 2003)

Book of Revelation Apocalyptic Epistle | ||

| Preceded by General Epistle of Jude |

New Testament Books of the Bible |

End |