Anthony of Padua

Anthony of Padua (Portuguese: António de Pádua; born Fernando Martins de Bulhões; 15 August 1195 – 13 June 1231[1]), also known as Anthony of Lisbon (Portuguese: António de Lisboa), was a Portuguese Catholic priest and friar of the Franciscan Order. He was born and raised by a wealthy family in Lisbon, Portugal, and died in Padua, Italy. Noted by his contemporaries for his powerful preaching, expert knowledge of scripture, and undying love and devotion to the poor and the sick, he was one of the most quickly canonized saints in church history. He was proclaimed a Doctor of the Church on 16 January 1946. He is also the patron saint of lost things.

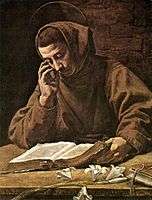

Saint Anthony of Padua | |

|---|---|

Anthony of Padua by Francisco de Zurbarán, 1627–1630 | |

| Evangelical Doctor Hammer of Heretics Professor of Miracles Doctor of the Church | |

| Born | 15 August 1195 Lisbon, Portugal |

| Died | 13 June 1231 (aged 35) Padua, Italy |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church |

| Beatified | 30 May 1232 |

| Canonized | 30 May 1232, Spoleto, Italy by Pope Gregory IX |

| Major shrine | Basilica of Saint Anthony of Padua, Italy |

| Feast | 13 June |

| Attributes | Book; bread; Infant Jesus; lily; fish; flaming heart; mule |

| Patronage | Lisbon, Lost items, lost people, lost souls, American Indians; amputees; animals; barrenness; Brazil; elderly people; faith in the Blessed Sacrament; fishermen; Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land; harvests; horses; lost articles; lower animals; mail; mariners; oppressed people; poor people; Portugal; pregnant women; seekers of lost articles; shipwrecks; starvation; sterility; swineherds; Tigua Indians; travel hostesses; travellers; Tuburan, Cebu; San Vicente, Sulat, Eastern Samar; Watermen; runts of litters; counter-revolutionaries; Pila, Laguna, Taytay, Rizal; Iriga, Camarines Sur; Camaligan, Camarines Sur |

Life

Early years

Fernando Martins de Bulhões was born in Lisbon, Portugal.[2] While 15th-century writers state that his parents were Vicente Martins and Teresa Pais Taveira, and that his father was the brother of Pedro Martins de Bulhões, the ancestor of the Bulhão or Bulhões family, Niccolò Dal-Gal views this as less certain.[2] His wealthy and noble family arranged for him to be instructed at the local cathedral school. At the age of 15, he entered the Augustinian community of Canons Regular of the Order of the Holy Cross at the Abbey of Saint Vincent on the outskirts of Lisbon.

In 1212, distracted by frequent visits from family and friends, he asked to be transferred to the motherhouse of the congregation, the Monastery of the Holy Cross in Coimbra, then the capital of Portugal.[3] There, the young Fernando studied theology and Latin.

Joining the Franciscans

After his ordination to the priesthood, Fernando was named guestmaster at the age of 19, and placed in charge of hospitality for the abbey. While he was in Coimbra, some Franciscan friars arrived and settled at a small hermitage outside Coimbra dedicated to Anthony of Egypt.[3] Fernando was strongly attracted to the simple, evangelical lifestyle of the friars, whose order had been founded only 11 years prior. News arrived that five Franciscans had been beheaded in Morocco, the first of their order to be killed. King Alfonso ransomed their bodies to be returned and buried as martyrs in the Abbey of Santa Cruz.[3] Inspired by their example, Fernando obtained permission from church authorities to leave the Canons Regular to join the new Franciscan order. Upon his admission to the life of the friars, he joined the small hermitage in Olivais, adopting the name Anthony (from the name of the chapel located there, dedicated to Anthony the Great), by which he was to be known.[4]

Anthony then set out for Morocco, in fulfillment of his new vocation. However, he fell seriously ill in Morocco and set sail back for Portugal in hope of regaining his health. On the return voyage, the ship was blown off course and landed in Sicily.[5]

From Sicily, he made his way to Tuscany, where he was assigned to a convent of the order, but he met with difficulty on account of his sickly appearance. He was finally assigned to the rural hermitage of San Paolo near Forlì, Romagna, a choice made after considering his poor health. There, he had recourse to a cell one of the friars had made in a nearby cave, spending time in private prayer and study.[6]

Preaching and teaching

One day in 1222, in the town of Forlì, on the occasion of an ordination, a number of visiting Dominican friars were present, and some misunderstanding arose over who should preach. The Franciscans naturally expected that one of the Dominicans would occupy the pulpit, for they were renowned for their preaching; the Dominicans, though, had come unprepared, thinking that a Franciscan would be the homilist. In this quandary, the head of the hermitage, who had no one among his own humble friars suitable for the occasion, called upon Anthony, whom he suspected was most qualified, and entreated him to speak whatever the Holy Spirit should put into his mouth.[5] Anthony objected, but was overruled, and his sermon created a deep impression. Not only his rich voice and arresting manner, but also the entire theme and substance of his discourse and his moving eloquence, held the attention of his hearers. Everyone was impressed with his knowledge of scripture, acquired during his years as an Augustinian friar.

At that point, Anthony was sent by Brother Gratian, the local minister provincial, to the Franciscan province of Romagna, based in Bologna.[5] He soon came to the attention of the founder of the order, Francis of Assisi. Francis had held a strong distrust of the place of theological studies in the life of his brotherhood, fearing that it might lead to an abandonment of their commitment to a life of real poverty. In Anthony, however, he found a kindred spirit for his vision, who was also able to provide the teaching needed by young members of the order who might seek ordination. In 1224, he entrusted the pursuit of studies for any of his friars to the care of Anthony.

The reason St. Anthony's help is invoked for finding things lost or stolen is traced to an incident that occurred in Bologna. According to the story, Anthony had a book of psalms that was of some importance to him, as it contained the notes and comments he had made to use in teaching his students. A novice who had decided to leave took the psalter with him. Prior to the invention of the printing press, any book was an item of value, and would have been difficult for a Franciscan friar to replace given his vow of poverty. Upon noticing it was missing, Anthony prayed it would be found or returned. The thief was moved to restore the book to Anthony and return to the order. The stolen book is said to be preserved in the Franciscan friary in Bologna.[7]

Occasionally, he took another post, as a teacher, for instance, at the universities of Montpellier and Toulouse in southern France, but as a preacher Anthony revealed his supreme gift. According to historian Sophronius Clasen, Anthony preached the grandeur of Christianity.[6] His method included allegory and symbolical explanation of Scripture. In 1226, after attending the general chapter of his order held at Arles, France, and spreading the word of the Lord in the French region of Provence, Anthony returned to Italy and was appointed provincial superior of northern Italy. He chose the city of Padua as his location.

In 1228, he served as envoy from the general chapter to Pope Gregory IX. At the papal court, his preaching was hailed as a "jewel case of the Bible" and he was commissioned to produce his collection of sermons, Sermons for Feast Days (Sermones in Festivitates). Gregory IX himself described him as the "Ark of the Testament" (Doctor Arca testamenti).

Legends

_-_attributed_to_Francisco_de_Herrera_the_Elder_(Detroit_Institute_of_Arts).png)

Anthony went to preach in Rimini, where the heretics treated him with contempt. So, instead he took himself to the shore-line and began to preach to the fish. A great crowd of fish arrayed themselves. The citizens flocked to see this marvel, and Anthony charged them with the fact that irrational creatures were more receptive than the unfaithful of Rimini, at which point the people gave ear to his sermons.[8]

In Toulouse, Anthony was challenged by a heretic to prove the reality of the presence of Christ in the Eucharist. The heretic brought a half-starved mule and waited to see its reaction when shown fresh fodder on one hand, and the sacrament on the other. The dumb animal ignored the fodder and bowed before the sacrament.[8]

Once in Italy, Anthony was dining with heretics, when he realized the food put before him was poisoned. When he reproached them for their conduct, they admitted to attempting to poison him, and dared him to eat if he truly believed the words spoken in Mark 16:18, "...and if they drink any deadly thing, it will not harm them." Anthony blessed the food, ate it, and suffered no harm, much to the amazement of his hosts.[8]

Death

Anthony became sick with ergotism in 1231, and went to the woodland retreat at Camposampiero with two other friars for a respite. There, he lived in a cell built for him under the branches of a walnut tree. Anthony died on the way back to Padua on 13 June 1231 at the Poor Clare monastery at Arcella (now part of Padua), aged 35.

According to the request of Anthony, he was buried in the small church of Santa Maria Mater Domini, probably dating from the late 12th century and near a convent which had been founded by him in 1229. Nevertheless, due to his increased notability, construction of a large basilica began around 1232, although it was not completed until 1301. The smaller church was incorporated into structure as the Cappella della Madonna Mora (Chapel of the Dark Madonna). The basilica is commonly known today as "Il Santo" (The Saint).

Various legends surround the death of Anthony. One holds that when he died, the children cried in the streets and that all the bells of the churches rang of their own accord. Another legend regards his tongue. Anthony is buried in a chapel within the large basilica built to honor him, where his tongue is displayed for veneration in a large reliquary along with his jaw and his vocal cords. When his body was exhumed 30 years after his death, it was found turned to dust, but the tongue was claimed to have glistened and looked as if it were still alive and moist; apparently a further claim was made that this was a sign of his gift of preaching.[9] On 1 January 1981, Pope John Paul II authorized a scientific team to study Anthony's remains and the tomb was opened on 6 January.[10]

Saint and Doctor of the Church

Anthony was canonized by Pope Gregory IX on 30 May 1232, at Spoleto, Italy, less than one year after his death.[2]

"The richness of spiritual teaching contained in the Sermons was so great that in [16 January] 1946 Venerable Pope Pius XII proclaimed Anthony a Doctor of the Church, attributing to him the title Doctor Evangelicus ["Evangelical Doctor"], since the freshness and beauty of the Gospel emerge from these writings."[11]

Veneration as patron saint

Anthony's fame spread through Portuguese evangelization, and he has been known as the most celebrated of the followers of Francis of Assisi. He is the patron saint of Lisbon, Padua and many places in Portugal and in the countries of the former Portuguese Empire.[12]

He is especially invoked and venerated all over the world as the patron saint for the recovery of lost items and is credited with many miracles involving lost people, lost things and even lost spiritual goods.[12][13]

St. Anthony Chaplets help devotees to meditate on the thirteen virtues of the saint. Some of these chaplets were used by members of confraternities which had Anthony as their patron saint.

North America

In 1692, Spanish missionaries came across a small Payaya Indian community along what was then known as the Yanaguana River on the feast day of Saint Anthony, 13 June. The Franciscan chaplain, Father Damien Massanet, with agreement from General Domingo de Teran, renamed the rivers in his honor, and eventually built a mission nearby, as well. This mission became the focal point of a small community that eventually grew in size and scope to become the seventh-largest city in the country, the U.S. city of San Antonio, Texas.[14]

In New York City, the Shrine Church of St. Anthony in Greenwich Village, Manhattan celebrates his feast day, starting with the traditional novena of prayers asking for his intercession on the 13 Tuesdays preceding his feast. This culminates with a week-long series of services and a street fair. A traditional Italian-style procession is held that day through the streets of its South Village neighborhood, during which a relic of the saint is carried for veneration.[15]

Each year on the weekend of the last Sunday in August, Boston's North End holds a feast in honor of Saint Anthony. Referred to as the "Feast of All Feasts", Saint Anthony's Feast in Boston's North End was begun in 1919 by Italian immigrants from Montefalcione, a small town near Naples, where the tradition of honoring Saint Anthony goes back to 1688.[16]

Each year the Sandia Pueblo along with Santa Clara Pueblo celebrates the feast day of Saint Anthony with traditional Native American dances.[17]

On 27 January 1907, in Beaumont, Texas, a church was dedicated and named in honor of Saint Anthony. The church was later designated a cathedral in 1966 with the formation of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Beaumont, but was not formally consecrated. On 28 April 1974, St. Anthony Cathedral was dedicated and consecrated by Bishop Warren Boudreaux. In 2006, Pope Benedict XVI granted the cathedral the designation of minor basilica. St. Anthony Cathedral Basilica celebrated its 100th anniversary on 28 January 2007.[18]

St. Anthony gives his name to Mission San Antonio de Padua, the third Franciscan mission dedicated along El Camino Real in California in 1771.[19]

In Ellicott City, Maryland, southwest of Baltimore, the Conventual Franciscans of the St. Anthony Province dedicated their old novitiate house as the Shrine of St. Anthony which since 1 July 2004 serves as the official shrine to Saint Anthony for the Archdiocese of Baltimore.[20]

Brazil and Europe

.jpg)

Saint Anthony is known in Portugal, Spain, and Brazil as a marriage saint, because legends exist of him reconciling couples. His feast day, 13 June, is Lisbon's municipal holiday, celebrated with parades and marriages (the previous day, 12 June, is the Dia dos Namorados in Brazil). He is one of the saints celebrated in the Brazilian Festa Junina, along with John the Baptist and Saint Peter. He is venerated in Mogán Village in Gran Canaria, where his feast day is celebrated every year with oversized objects carried through the streets for the fiesta.[21]

In the town of Brusciano, Italy, located near Naples, an annual feast in honor of Saint Anthony is held in late August. This tradition dates back to 1875. The tradition started when a man prayed to Saint Anthony for his sick son to get better. He vowed that if his son would become healthy that he would build and dance a giglio like the people of Nola do for their patron San Paolino during the annual Fest Dei Gigli. (A giglio is a tall tower topped with a statue of the saint that is carried through the streets in carefully choreographed maneuvers that resemble a dance.) The celebration has grown over the years to include six giglio towers built in honor of the saint. This tradition has also carried over to America, specifically the East Harlem area of New York, where the immigrants from the town of Brusciano formed the Giglio Society of East Harlem and have been holding their annual feast since the early 1900s.[22]

In Albania, the Franciscans arrived in 1240 spreading the word of Saint Anthony. The St. Anthony Church, Laç (Albanian: Kisha e Shna Ndout or Kisha e Laçit) in Laç was built in his honor.[23]

In Poland, he is the patron saint of Przeworsk. The icon of Saint Anthony, dating from 1649, is housed in a local (Franciscan church, Kaplica Świętego Antoniego w Przeworsku).

Asia

Devotion to Saint Anthony is popular throughout all of India. In Uvari, in Tamil Nadu, India, the church of Saint Anthony is home to an ancient wooden statue that is said to have cured the entire crew of a Portuguese ship suffering from cholera. Saint Anthony is said to perform many miracles daily, and Uvari is visited by pilgrims of different religions from all over South India. Christians in Tamil Nadu have great reverence for Saint Anthony and he is a popular saint there, where he is called the "Miracle Saint."

Also in India, a small crusady known with the name of Saint Anthony is located in the village called Pothiyanvilai, state of Tamil Nadu Kanyakumari district near Thengapattinam, where thousands of devotees attend every Tuesday and Friday to receive his blessings, miracles, and guidings directly from St. Anthony's soul entering in the body of a holy person for the last 34 years. The southern Indian state of Karnataka is also a holy pilgrimage center in honor of Saint Anthony (specifically located in the small village of Dornahalli, near Mysore). Local lore holds that a farmer there unearthed a statue that was later identified as being that of Saint Anthony. The statue was deemed miraculous and an incident of divine intervention. A church was then erected to honor the saint. Additionally, Saint Anthony is highly venerated in Sri Lanka, and the nation's Saint Anthony National Shrine in Kochikade, Colombo, receives many devotees of Saint Anthony, both Catholic and non-Catholic. There is also a church in Pakistan of Saint Anthony of Padua in the city of Sargodha under the Diocese of Rawalpindi.

In the Philippines, the devotion to St. Anthony of Padua began in 1581, in the town of Pila, Laguna, where Franciscans established the first church in the country dedicated to St. Anthony of Padua, now elevated as the National Shrine of St. Anthony of Padua under the Diocese of San Pablo.

In Siolim, a village in the Indian state of Goa, St. Anthony is always shown holding a serpent on a stick. This is a depiction of the incident which occurred during the construction of the church wherein a snake was disrupting construction work. The people turned to St. Anthony for help and placed his statue at the construction site. The next morning, the snake was found caught in the cord placed in the statue's hand.[24]

In art

As the number of Franciscan saints increased, iconography struggled to distinguish Anthony from the others. Because of a legend that he had once preached to the fish by the mouth of the river Marecchia in Rimini, this was sometimes used as his attribute. He is also often seen with a white lily stalk, representing his purity. Other conventions referred to St. Anthony's visionary fervor. Thus, one attribute in use for some time was a flaming heart. He is also sometimes depicted along with the mule in Rimini that allegedly bowed down to him holding the Eucharist.

In 1511, Titian painted three large frescoes in the Scuola del Santo in Padua, depicting scenes of the miracles from the life of Saint Anthony: The Miracle of the Jealous Husband, which depicts the murder of a young woman by her husband; A Child Testifying to Its Mother's Innocence; and The Saint Healing the Young Man with a Broken Limb.[25]

Another key pattern has him meditating on an open book in which the Christ Child himself appears, as in the El Greco above. Over time the child came to be shown considerably larger than the book and some images even do without the book entirely. He typically appears carrying the infant Jesus and holding a cross.[26]

In popular votive offerings, Anthony is often depicted as miraculously saving individuals in various accidents.[27]

- Anthony of Padua in Art

An early work by Raphael, 1503, at the Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, UK

An early work by Raphael, 1503, at the Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, UK Baby Jesus with St. Anthony of Padua, Elisabetta Sirani, 1656, Bologna, Italy

Baby Jesus with St. Anthony of Padua, Elisabetta Sirani, 1656, Bologna, Italy Anthony of Padua with the Infant Jesus by Antonio de Pereda

Anthony of Padua with the Infant Jesus by Antonio de Pereda St Antony Reading, early 17th century, by Marco Antonio Bassetti

St Antony Reading, early 17th century, by Marco Antonio Bassetti Triptych of Saint Antonius by Ambrosius Benson

Triptych of Saint Antonius by Ambrosius Benson Saint Anthony of Padua with the Infant Christ by Guercino, 1656, Bologna, Italy

Saint Anthony of Padua with the Infant Christ by Guercino, 1656, Bologna, Italy Vision of Saint Anthony, by Alonso Cano

Vision of Saint Anthony, by Alonso Cano St. Antony with Christ Child, from, Carinthia, in Austria

St. Antony with Christ Child, from, Carinthia, in Austria Saint Anthony of Padua and the miracle of the mule, by Anthony van Dyck.

Saint Anthony of Padua and the miracle of the mule, by Anthony van Dyck. St. Anthony of Padua Preaching to the Fish, by Victor Wolfvoet II.

St. Anthony of Padua Preaching to the Fish, by Victor Wolfvoet II. St Anthony holding Baby Jesus

St Anthony holding Baby Jesus

In films

- The 1931 silent film Saint Anthony of Padua (Antonio di Padova, il santo dei miracoli) was directed by Giulio Antamoro.

- He was played in the 1949 Italian film Anthony of Padua by Aldo Fiorelli.

- Umberto Marino's 2002 Sant'Antonio di Padova or Saint Anthony: The Miracle Worker of Padua is an Italian TV movie about the saint.[28] While the VHS format is without English subtitles,[29] the DVD version released in 2005 is simply called Saint Anthony and is subtitled.[30]

- Antonello Belluco's 2006 Antonio guerriero di Dio or Anthony, Warrior of God[31] is a biopic about the saint.[32]

- João Pedro Rodrigues directed the 2016 film The Ornithologist, a sort of modern-day fantastic allegory of the life of St. Anthony.

See also

| Part of a series on | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Christian mysticism | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Theology · Philosophy

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Practices

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

People (by era or century)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Literature · Media

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- List of Latin nicknames of the Middle Ages: Doctors in theology

- Basilica of Saint Anthony of Padua

- Marian doctrines of St. Anthony

References

- Purcell, Mary (1960). Saint Anthony and His Times. Garden City, New York: Hanover House. pp. 19, 275–6.

- Dal-Gal, Niccolò (1907). "St. Anthony of Padua". The Catholic Encyclopedia. 1. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- Monti, Dominic V. (O.F.M.) (2008). Francis and His Brothers. A Popular History of the Franciscan Friars. Cincinnati, Ohio: Franciscan Media. ISBN 978-0-86716855-6. Excerpt. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- José Manuel Azevedo Silva (2011), p.1

- "Anthony of Padua: The Italian Years - June 2007 Issue of St. Anthony Messenger Magazine Online". 30 June 2007. Archived from the original on 30 June 2007.

- Foley, Leonard. "Who Is St. Anthony?". American Catholic. Archived from the original on 17 October 2000. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- "Finding the Real St. Anthony: Devotion to St. Anthony of Padua". 8 December 2000. Archived from the original on 8 December 2000.

- Arnald of Sarrant, Chronicle of the Twenty-Four Generals of the Order of Friars Minor, (Noel Muscat, trans.) Ordo Fratrum Minorum. Malta, 2010. pp. 122–125.

- "Skeleton of St Anthony goes on display to public more than 750 years after his death". Daily Mail. 15 February 2010. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- "When Anthony spoke again". Messenger of Saint Anthony. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- Pope Benedict XVI (10 February 2010). "GENERAL AUDIENCE". Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- "Novena to Saint Anthony to Find a Lost Article - Prayer to Saint Anthony of Padua - Novena to Find a Lost Item". 14 November 2007. Archived from the original on 14 November 2007.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "San Antonio: The City of St. Anthony". St. Anthony Messenger Magazine Online. Americancatholic.org. June 2004. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- "Mass Schedule". stanthonynyc.org. Archived from the original on 5 November 2009.

- Aluia, Jason (19 August 2013). "94th St. Anthony's Feast Schedule Highlights – Friday, August 23 – Monday, August 26, 2013". North End Waterfront.com. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- Sweet, Jill Drayson (2004). Dances of the Tewa Pueblo Indians: expressions of new life. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press. ISBN 978-1-930618-29-9.

- "St. Anthony Cathedral Basilica". Forest Trail Region.

- "The History of our Mission". Mission San Antonio de Padua.

- "At Shrine of St. Anthony, a taste of history and a sense of peace". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- Media, Mogan. "Church of San Antonio El Chico". www.moganguide.com.

- Green, Frank. "Parishioners will hoist nearly 4-ton wooden tower during Dance of the Giglio Festival". nydailynews.com.

- Merlika, Eugjen (13 June 2015). "Historia e Kishës së Laçit! Shenjti portugez i shqiptarëve". Mapo. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- "Siolim The Village Everyone Loves | St.Mary's Goan Community Dubai". 6 June 2012. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014.

- Morosini, Sergio Rossetti (March 1999). "New Findings in Titian's Fresco Technique at the Scuola del Santo in Padua". The Art Bulletin. 81 (1): 163–164. doi:10.2307/3051293. JSTOR 3051293.

- Chong, Alan, ed. Christianity in Asia: Sacred Art and Visual Splendour. Printed in Singapore for the Asian Civilisations Museum: Dominie Press, 2016, p. 189.

- Museum of Popular Devotion, Basilica of Saint Anthony, Padua

- Sant'Antonio di Padova aka Saint Anthony: The Miracle Worker of Padua at IMDb.

- VHS on Amazon.

- DVD on Amazon.

- DVD on Amazon with English subtitles.

- Antonio guerriero di Dio aka Anthony, Warrior of God at IMDb.

Further reading

- St. Anthony, Doctor of the Church, Franciscan Institute Publications, 1973, ISBN 978-0-8199-0458-4

- Anthony of Padua, Sermones for the Easter Cycle, Franciscan Institute Publications, 1994, ISBN 978-1-57659-041-6

- Attwater, Donald; John, Catherine Rachel (1993), The Penguin Dictionary of Saints (3rd ed.), New York, New York: Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-051312-7

- Silva, José Manuel Azevedo (2011), Câmara Municipal (ed.), A criação da freguesia de Santo António dos Olivais: Visão Histórica e Perspectivas Actuais (PDF) (in Portuguese), Santo António dos Olivias (Coimbra), Portugal: Câmara Municipal de Santo António dos Olivais, archived from the original (PDF) on 20 December 2011, retrieved 5 September 2011

External links

![]()

- Basilica of Saint Anthony of Padua – Official website

- Church of Saint Anthony of Lisbon – Official website

- "Saint Anthony of Padua" at the Christian Iconography website

- "St Anthony of Padua – St Peter's Square Colonnade Saints"

- "Saint Anthony of Padua". Invisible Monastery of charity and fraternity - Christian family prayer. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018.