Our Lady of Lourdes

Our Lady of Lourdes is a Roman Catholic title of the Blessed Virgin Mary venerated in honour of the Marian apparitions that occurred in 1858 in the vicinity of Lourdes in France. The first of these is the apparition of 11 February 1858, when 14-year old Bernadette Soubirous told her mother that a "lady" spoke to her in the cave of Massabielle (a kilometre and a half (1 mi) from the town) while she was gathering firewood with her sister and a friend.[3] Similar apparitions of the "Lady" were reported on eighteen occasions that year, until the climax revelation of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception took place.[4]

| Our Lady of Lourdes Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception | |

|---|---|

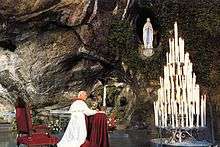

.jpg) The statue within the rock cave at Massabielle in Lourdes, where Saint Bernadette Soubirous claimed to have witnessed the Blessed Virgin Mary, though she disapproved of this artistic depiction. Now a religious grotto. | |

| Location | Lourdes, France |

| Date | 11 February to 16 July 1858 |

| Witness | Saint Bernadette Soubirous |

| Type | Marian apparition |

| Approval | January 18, 1862[1][2] Bishop Bertrand-Sévère Laurence Diocese of Tarbes |

| Shrine | Sanctuary of Our Lady of Lourdes, Lourdes, France |

| Patronage | Lourdes, France, Quezon City, Tagaytay City, Barangay Granada of Bacolod City, Daegu, South Korea, Tennessee, Diocese of Lancaster, bodily ills, sick people, protection from diseases |

| Feast day | February 11 |

In 18 January 1862, the local Bishop of Tarbes Bertrand-Sévère Laurence endorsed the veneration of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Lourdes. On 3 July 1876, Pope Pius IX officially granted a Canonical Coronation to the image that used to be in the courtyard of what is now part of the Rosary Basilica.[5][6] The image of Our Lady of Lourdes has been widely copied and reproduced in shrines and homes, often in garden landscapes. Soubirous was later canonized as a Catholic saint by Pope Pius XI in 1933.[7][8]

After church investigations confirmed her visions, a large church was built at the site.[9] Lourdes is now a major Marian pilgrimage site: within France, only Paris has more hotels than Lourdes.

Apparitions

On 11 February 1858, Soubirous went with her sister Toinette and neighbor Jeanne Abadie to collect some firewood. After taking off her shoes and stockings to wade through the water near the Grotto of Massabielle, she said she heard the sound of two gusts of wind (coups de vent) but the trees and bushes nearby did not move. A wild rose in a natural niche in the grotto, however, did move.

“…I came back towards the grotto and started taking off my stockings. I had hardly taken off the first stocking when I heard a sound like a gust of wind. Then I turned my head towards the meadow. I saw the trees quite still: I went on taking off my stockings. I heard the same sound again. As I raised my head to look at the grotto, I saw a lady dressed in white, wearing a white dress, a blue girdle and a yellow rose on each foot, the same color as the chain of her rosary; the beads of the rosary were white....From the niche, or rather the dark alcove behind it, came a dazzling light…”.[10]

Soubirous tried to make the sign of the Cross but she could not, because her hands were trembling. The lady smiled, and invited Soubirous to pray the rosary with her.[11] Soubirous tried to keep this a secret, but Toinette told her mother. After parental cross-examination, she and her sister received corporal punishment for their story.[12]

Three days later, 14 February, Soubirous returned to the Grotto. She had brought holy water as a test that the apparition was not of evil origin/provenance: "The second time was the following Sunday. ... Then I started to throw holy water in her direction, and at the same time I said that if she came from God she was to stay, but if not, she must go. She started to smile, and bowed ... This was the second time."[13]

Soubirous's companions are said to have become afraid when they saw her in ecstasy. She remained ecstatic even as they returned to the village. On 18 February, she spoke of being told by the Lady to return to the Grotto over a period of two weeks. She quoted the apparition: "The Lady only spoke to me the third time. ... She told me also that she did not promise to make me happy in this world, but in the next."[12]

Soubirous was ordered by her parents to never go there again. She went anyway, and on 24 February, Soubirous related that the apparition asked for prayer and penitence for the conversion of sinners.

The next day, she said the apparition asked her to dig in the ground and drink from the spring she found there. This made her dishevelled and some of her supporters were dismayed, but this act revealed the stream that soon became a focal point for pilgrimages.[14] Although it was muddy at first, the stream became increasingly clean. As word spread, this water was given to medical patients of all kinds, and many reports of miraculous cures followed. Seven of these cures were confirmed as lacking any medical explanations by Professor Verges in 1860. The first person with a "certified miracle" was a woman whose right hand had been deformed as a consequence of an accident. Several miracles turned out to be short-term improvement or even hoaxes, and Church and government officials became increasingly concerned.[15] The government fenced off the Grotto and issued stiff penalties for anybody trying to get near the off-limits area. In the process, Lourdes became a national issue in France, resulting in the intervention of Emperor Napoleon III with an order to reopen the grotto on 4 October 1858. The Church had decided to stay away from the controversy altogether.

Soubirous, knowing the local area well, managed to visit the barricaded grotto under cover of darkness. There, on 25 March, she said she was told: "I am the Immaculate Conception" ("que soy era immaculada concepciou"). On Easter Sunday, 7 April, her examining doctor stated that Soubirous, in ecstasy, was observed to have held her hands over a lit candle without sustaining harm. On 16 July, Soubirous went for the last time to the Grotto. "I have never seen her so beautiful before," she reported.[15]

The Church, faced with nationwide questions, decided to institute an investigative commission on 17 November 1858. On 18 January 1860, the local bishop finally declared that: "The Virgin Mary did appear indeed to Bernadette Soubirous."[15] These events established the Marian veneration in Lourdes, which together with Fátima and the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe is one of the most frequented Marian shrines in the world, and to which between 4 and 6 million pilgrims travel annually.

In 1863, Joseph-Hugues Fabisch was charged to create a statue of the Virgin according to Soubirous's description. The work was placed in the grotto and solemnly dedicated on 4 April 1864 in presence of 20,000 pilgrims.

The veracity of the apparitions of Lourdes is not an article of faith for Catholics. Nevertheless, all recent Popes visited the Marian shrine at some time. Benedict XV, Pius XI, and John XXIII went there as bishops, Pius XII as papal delegate. He also issued an encyclical, Le pèlerinage de Lourdes, on the one-hundredth anniversary of the apparitions in 1958. John Paul II visited Lourdes three times during his pontificate, and twice before as a bishop.

Bernadette's description of Mary

Soubirous described the apparition as uo petito damizelo ("a tiny maiden") of about twelve years old. Soubirous insisted that the apparition was no taller than herself. At 1.40 metres (4 ft 7 in) tall, Soubirous was diminutive even by the standards of other poorly nourished children.[16]

Soubirous described that the apparition as dressed in a flowing white robe, with a blue sash around her waist. This was the uniform of a religious group called the Children of Mary, which, on account of her poverty, Soubirous was not permitted to join (although she was admitted after the apparitions).[17] Her Aunt Bernarde was a long-time member.

The statue that currently stands in the niche within the grotto of Massabielle was created by the Lyonnais sculptor Joseph-Hugues Fabisch in 1864. Although it has become an iconographic symbol of Our Lady of Lourdes, it depicts a figure which is not only older and taller than Soubirous's description, but also more in keeping with orthodox and traditional representations of the Virgin Mary. On seeing the statue, Soubirous was profoundly disappointed with this representation of her vision.[18]

Similar events

In nearby Lestelle-Bétharram, only a few kilometres from Lourdes, some shepherds guarding their flocks in the mountains observed a vision of a ray of light that guided them to the discovery of a statue of the Virgin Mary. Two attempts were made to remove the statue to a more prominent position; each time it disappeared and returned to its original location, at which a small chapel was built for it.[19]

In the early sixteenth century, a twelve-year-old shepherdess called Anglèze de Sagazan received a vision of the Virgin Mary near the spring at Garaison (part of the commune of Monléon-Magnoac), somewhat further away. Anglèze's story is strikingly similar to that of Soubirous: she was a pious but illiterate and poorly educated girl, extremely impoverished, who spoke only in the local language, Gascon Occitan, but successfully convinced authorities that her vision was genuine and persuaded them to obey the instructions of her apparitions. Like Soubirous, she was the only one who could see the apparition (others could apparently hear it); however, the apparition at Garaison's supernatural powers tended toward the miraculous provision of abundant food, rather than healing the sick and injured. Mid-nineteenth century commentators noted the parallels between the events at Massabielle and Garaison, and interpreted the similarities as proof of the divine nature of Soubirous's claims.[20] At the time of Soubirous, Garaison was a noted center of pilgrimage and Marian devotion.

There are also several similarities between the apparition at La Salette, near Grenoble, and Lourdes. La Salette is many hundreds of kilometres from Lourdes, and the events at La Salette predate those in Lourdes by 12 years. However, Virgin Mary's appearance of La Salette was tall and maternal (not petite and gentle like her Lourdes apparition) and had a darker, more threatening series of messages. It is not certain if Soubirous was aware of the events at La Salette.[21]

Approval by the Catholic Church

Approval by the local bishop

On 18 January 1862, the Bishop of Tarbes Betrand Severt Laurence declared the following regarding the alleged Marian apparitions:

"We are inspired by the Commission comprising wise, holy, learned and experienced priests who questioned the child, studied the facts, examined everything and weighed all the evidence. We have also called on science, and we remain convinced that the Apparitions are supernatural and divine, and that by consequence, what Soubirous saw was the Most Blessed Virgin. Our convictions are based on the testimony of Soubirous, but above all on the things that have happened, things which can be nothing other than divine intervention."[22]

Pontifical approbations

- Pope Pius IX approved the veneration in Lourdes and supported the building of the Cathedral in 1870 to which he donated several gifts. He approved indulgences and issued a Canonical coronation to the courtyard image of the basilica on 3 July 1876.[23]

- Pope Leo XIII issued an apostolic letter Parte Humanae Generi in commemoration of the consecration of the new Cathedral in Lourdes in 1879. He later issued a Canonical coronation towards an image of Lourdes for India on 8 May 1886. [24]

- As Archbishop of Bologna, future Pope Giacomo Paolo Giovanni Battista della Chiesa organized a diocesan pilgrimage to Lourdes, requesting for Marian veneration in that area.

- Pope Pius X in 1907 introduced the feast of the apparition of the Immaculate Virgin of Lourdes. In the same year he issued his encyclical Pascendi dominici gregis, in which he specifically repeated the permission to venerate the virgin in Lourdes.[25]

- Pope Pius XI in 1937 nominated future Pope Eugenio Pacelli as his 'Papal Delegate' to personally visit and venerate in Lourdes. The same Pontiff beatified Soubirous on 6 June 1925 and canonized her on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception on 8 December 1933 and determined her Feast Day to be 18 February.[26] [27]

- Pope Pius XII issued a Papal encyclical Le pèlerinage de Lourdes on the 100th centenary anniversary of the Marian apparitions of Lourdes.

- As Archbishop of Milan, future Pope Giovanni Battista Montini visited Lourdes.

- Pope John Paul II made three religious pilgrimages to Lourdes.

- Pope Benedict XVI issued a novelty coronation towards the Lourdes image on World Day of the Sick in 2007. In September 2008, he visited Lourdes commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Marian apparitions.

- Pope Francis granted a Canonical coronation towards a Lourdes image for the Philippines on 5 September 2019.

Reported healings

The location of the spring was described to Soubirous by an apparition of Our Lady of Lourdes on 25 February 1858. Since that time many thousands of pilgrims to Lourdes have followed the instruction of Our Lady of Lourdes to "drink at the spring and wash in it".

Although never formally encouraged by the Church, Lourdes water has become a focus of devotion to the Virgin Mary at Lourdes. Since the apparitions, many people have claimed to have been cured by drinking or bathing in it,[28] and the Lourdes authorities provide it free of charge to any who ask for it.[29]

An analysis of the water was commissioned by then mayor of Lourdes, Anselme Lacadé in 1858. It was conducted by a professor in Toulouse, who determined that the water was potable and that it contained the following: oxygen, nitrogen, carbonic acid, carbonates of lime and magnesia, a trace of carbonate of iron, an alkaline carbonate or silicate, chlorides of potassium and sodium, traces of sulphates of potassium and soda, traces of ammonia, and traces of iodine.[30] Essentially, the water is quite pure and inert. Lacadé had hoped that Lourdes water might have special mineral properties which would allow him to develop Lourdes into a spa town, to compete with neighbouring Cauterets and Bagnères-de-Bigorre.[28]

The Lourdes Medical Bureau

To ensure claims of cures were examined properly and to protect the town from fraudulent claims of miracles, the Lourdes Medical Bureau (Bureau Medical) was established at the request of Pope Pius X. It is completely under medical rather than ecclesiastical supervision. Approximately 7000 people have sought to have their case confirmed as a miracle, of which 69 have been declared a scientifically inexplicable miracle by both the Bureau and the Catholic Church.[31]

The Sanctuary

The Sanctuary of Our Lady of Lourdes or the Domain (as it is most commonly known) is an area of ground surrounding the shrine (Grotto) to Our Lady of Lourdes in the town of Lourdes, France. This ground is owned and administered by the Church, and has several functions, including devotional activities, offices, and accommodation for sick pilgrims and their helpers. The Domain includes the Grotto itself, the nearby taps which dispense the Lourdes water, and the offices of the Lourdes Medical Bureau, as well as several churches and basilicas. It comprises an area of 51 hectares, and includes 22 separate places of worship.[32] There are six official languages of the Sanctuary: French, English, Italian, Spanish, Dutch and German.

The sanctuary is visited by millions each year, and Lourdes has become one of the prominent pilgrimage sites of the world. Large numbers of sick pilgrims travel to Lourdes each year in the hope of physical healing or spiritual renewal.

Replicas

- The University of Notre Dame (Notre Dame, IN, USA) has a replica one-seventh the size of the famed French shrine. It was built in 1896 and is called the Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes, or, the Grotto.

- The Church of Notre Dame (New York City) is an affiliated Church of Our Lady of Lourdes. It is dedicated to her veneration and Lourdes waters are available to pilgrims at the New York church, with the 1910 interior constructed as a faithful, large-scale replica of the Grotto.

- Scotland's Carfin Grotto includes a replica of Our Lady of Lourdes.

- Mount Saint Mary's University, Emmitsburg, MD National Shrine Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes.

- Saint Mary-of-the-Woods, Sisters of Providence National Historic District has a replica Shrine depicting the Our Lady of Lourdes as a grotto.

- The Shrine of the Most Blessed Sacrament in Hanceville, AL includes a replica of the Lourdes Grotto

- The Grotto, Our Lady of Lourdes Shrine at the Shrine of St. Therese of Lisieux in Nesquehoning, PA, US - National Register of Historic Places

In popular culture

- In 1939, Henry K. Dunn directed Miracle at Lourdes for MGM's Miniature series. It is a short film about a terminally ill woman who hopes to be healed at the shrine.

- In 1943, the events became the basis of the film The Song of Bernadette. Jennifer Jones played the title role while Linda Darnell portrayed the Virgin Mary. The film won several Academy Awards, including an Academy Award for Best Actress for Jones.[33]

- In 1959, singer Andy Williams recorded a song entitled "The Village of St. Bernadette".[34]

- In 1961 Daniéle Ajoret portrayed Bernadette in Bernadette of Lourdes (French title: Il suffit d'aimer or Love is Enough) of Robert Darène.[35][36]

- Also in 1959, Loretta Young filmed "The Road", an episode of her popular television show, in Lourdes.

- The 2007 film The Diving Bell and the Butterfly features a flashback in which Jean-Dominique Bauby travels to Lourdes with a girlfriend and walks through the streets of the town.

- In 2009 Jessica Hausner wrote and directed the French feature film Lourdes starring Sylvie Testud. The fictional drama tells the story of wheelchair-bound Christine, who in order to escape her isolation, makes a life changing journey to Lourdes, the iconic site of pilgrimage in the Pyrenees.[37]

- In 2015–16, singer-songwriter Michael Knott recorded a song entitled "Lady of Lourdes".[38]

See also

- Le pèlerinage de Lourdes

- Lourdes apparitions

- Marian apparition

Notes

- The event was not a rite of Canonical coronation, nor a re-coronation of the image at the Rosary basilica.

References

Citations

- Spano, Susan (2008-09-07). "Lourdes, France, through the centuries". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2019-10-08.

1862: After questioning Bernadette, Bishop Bertrand-Severe Laurence of the diocese of Tarbes (later Tarbes and Lourdes) confirms the apparitions.

- Laurence, Bertrand (1862-01-18). "Report of the Episcopal Commission". Miracle Hunter.

- Catholic Online: Apparitions of Our Lady of Lourdes First Apparition Archived April 12, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- 2009 Catholic Almanac. Our Sunday Visitor Publishing.

- "La Vierge couronnée - Lourdes".

- "Marie Reine, 22 août", Zenit, 21 Août 2013

- Burke, Raymond L.; et al. (2008). Mariology: A Guide for Priests, Deacons, Seminarians, and Consecrated Persons ISBN 978-1-57918-355-4 pp. 850-868

- Lauretin, R., Lourdes, Dossier des documents authentiques, Paris: 1957

- Buckley, James; Bauerschmidt, Frederick Christian, and Pomplun, Trent. The Blackwell Companion to Catholicism, 2010 ISBN 1444337327 p. 317

- Taylor, Thérèse (2003). Bernadette of Lourdes. Burns and Oates. ISBN 0-86012-337-5

- Fr. Paolo O. Pirlo, SHMI (1997). "Our Lady of Lourdes". My First Book of Saints. Sons of Holy Mary Immaculate - Quality Catholic Publications. pp. 49–50. ISBN 971-91595-4-5.

- Laurentin 1988, p. 161.

- Harris 1999, p. 4.

- Harris 1999, p. 7.

- Lauretin 1988, p. 162.

- Harris 1999, p. 72.

- Harris 1999, p. 43.

- Visentin, M.C. (2000). "María Bernarda Soubirous (Bernardita)". In Leonardi, C.; Riccardi, A.; Zarri, G. (eds.). Diccionario de los Santos (in Spanish). Spain: San Pablo. pp. 1586–1596. ISBN 84-285-2259-6.

- Harris 1999, p. 39.

- Harris 1999, p. 41.

- Harris 1999, p. 60.

- "Lourdes".

- Schmidlin, Josef.Papstgeschichte, München 1934, 317

- Bäumer Leo XIII, Marienlexikon, 97

- Bäumer, Pius X Marienlexikon, 246

- Hahn Baier, Bernadette Soubirous, Marienlexikon, 217

- "Apparitions at Lourdes".

- Harris, Ruth. Lourdes: Body and Spirit in the Secular Age, Penguin Books, 2000, p. 312.

- Clarke, Richard. 2008 Lourdes, Its Inhabitants, Its Pilgrims, And Its Miracles ISBN 1-4086-8541-8 p. 38

- Barbé, Daniel. Lourdes

- Where Scientists are looking for God, The Telegraph, 16 January 2002. Retrieved 7 August 2012

- "Lourdes".

- "NY Times: The Song of Bernadette". NY Times. Retrieved 2008-12-15.

- Andy Williams, "The Village of St. Bernadette" chart positions Retrieved June 6, 2013

- Theatrical poster.

- Christophe Ruiz. "Cinéma: Un festival "Lourdes au cinéma"".

- Hausner's Lourdes wins Viennale best film award. Screen daily.com, 4 November 2009.

- Michael Knott - Songs From The Feather River Highway EP. Knottheads.com, Retrieved June 4, 2016

Works cited

- Glynn, Paul (2003). Healing Fire of Christ: Reflections on Modern Miracles. Ignatius Press.

- Harris, Ruth (1999). Lourdes: 0irit in the Secular Age. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-71-399186-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Laurentingeneral, L. (1988). "Lourdes". Marienlexikon. Regensburg: Eos Verlag.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marnham, Patrick (1982). Lourdes, A Modern Pilgrimage. Image Books.

External links

- Sanctuary of Our Lady of Lourdes – Official website

- The Grotto of the Apparitions – Online transmissions

- The cures at Lourdes recognised as miraculous by the Church

- Pilgrimage of His Holiness John Paul II to Lourdes on the Occasion of the 150th Anniversary of the Promulgation of the Dogma of the Immaculate Conception