Pelagianism

Pelagianism is a heterodox Christian theological position which holds that the original sin did not taint human nature and that mortal will is capable of choosing good or evil without divine aid or assistance. This theological theory is named after the British monk Pelagius (c. 355 – c. 420 CE), although he denied, at least at some point in his life, many of the doctrines associated with his name. Pelagianism asserts human will, as created with its abilities by God, is sufficient to live a sinless life, although God's grace assists every good work. It has come to be identified with the view (whether taught by Pelagius or not) that human beings can earn salvation by their own efforts.

Pelagian controversy

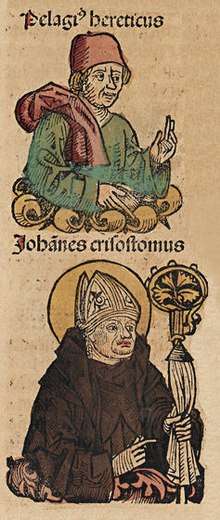

Pelagius (c. 355–c. 420 CE)[1] was a monk, probably from the British Isles, who moved to Rome in the mid-380s.[2] At the time, many Romans were converting to Christianity, but they did not necessarily follow the faith strictly.[3] Pelagius criticized what he saw as an increasing laxity among Christians, instead promoting higher moral standards and Christian asceticism.[1][4] He defended asceticism from the accusation of Manicheanism and argued for the possibility of a sinless life. Pelagius was not the first to reject original sin, an idea already promoted by Rufinus the Syrian.[5] Pelagius and his ideas were most popular among circles of the Roman elite, who adopted lay asceticism as a way of life.[2][4] Other prominent Pelagians included the former Roman aristocrat Caelestius, described by Gerald Bonner as "the real apostle of the so-called Pelagian movement", and the apologist Julian of Eclanum.[5] According to scholar Ali Bonner, the ideas Pelagius actually promoted were not a "new heresy", as Augustine claimed,[6] but mainstream in contemporary Christianity, advocated by such figures as Athanasius of Alexandria, Jerome, and others.[7]

In 412, Augustine read Pelagius' Commentary on Romans and described its author as a "highly advanced Christian", although he disagreed with Pelagius' exegesis of Romans 5:12, which he believed downplayed original sin.[8] Augustine maintained friendly relations with Pelagius until the next year, initially only condemning Caelestius' teachings.[5] In 415, the exiled Gallic bishops Heros of Arles and Lazarus of Aix accused Pelagius of heresy; Pelagius defended himself by claiming not to teach what he was accused of and by ascribing some of the teachings to Caelestinus and disavowing them, leading to his acquittal at the Council of Diospolis in Lod. Following the verdict, Augustine led condemnation of Pelagius in Africa and persuaded Pope Innocent I to condemn Pelagianism. In January 417, shortly before his death, Innocent excommunicated Pelagius and two of his followers. Innocent's successor, Zosimus, initially agreed to reopen the case against Pelagius, but backtracked following pressure from the African bishops.[5][9] Pelagianism was later condemned at the Council of Carthage (418),[10] after which Zosimus issued the Epistola tractoria excommunicating both Pelagius and Caelestinus.[5] The condemnation of Pelagianism was ratified at the Council of Ephesus.[11]

At the time, Pelagius' teachings had considerable support among Christians, especially other monks.[12] Eighteen Italian bishops, including Julian of Eclanum, had protested the condemnation of Pelagius; Julian continued to preach Pelagianism after 418. However, Pelagianism ceased to be a viable doctrine in the Latin West after many of its supporters were condemned or forced to move to the East.[13] Despite repeated attempts to suppress Pelagianism and similar teachings by orthodox clergy, some followers were still active in the Ostrogothic Kingdom (493–553), most notably in Picenum and Dalmatia during the rule of Theoderic the Great.[14] Pelagianism was also reported to be popular in Britain, as Germanus of Auxerre had to make at least one visit (in 429) to denounce the heresy. Some scholars, including Nowell Myres and John Morris, have suggested that Pelagianism in Britain was understood as an attack on Roman decadence and corruption, but this has been criticized by others such as Wolf Liebeschuetz.[5]

Beliefs

Influenced by an Eastern tradition that was more positive on human nature,[15][16] Pelagius believed that the doctrine of original sin placed too little emphasis on the human capacity for self-improvement, leading either to despair or to reliance on forgiveness without responsibility.[15] He taught that humans were free of the burden of original sin, because it would be unjust for any person to be blamed for another's actions.[12] He believed that Adam's transgression had caused humans to become mortal, and given them a bad example, but not corrupted their nature.[17][lower-alpha 1] Pelagius reasoned that it would be unreasonable for God to command the impossible,[15] and therefore each human retained complete freedom of action and full responsibility for all actions.[12] In other words, sin is not an inevitable result of fallen human nature, but instead comes about by free choice.[19] Because a person always has the ability to choose the right action in each circumstance, it is therefore theoretically possible (though rare) to live a sinless life.[12][20] Pelagius taught that a human's ability to act correctly is a gift of God,[20] as well as divine revelation and the example and teachings of Jesus. Further spiritual development, including faith in Christianity, was up to individual choice, not divine benevolence.[12][21] Because sin must be deliberate and people are only responsible for their own actions, infants are without fault and unbaptized infants will not be sent to hell.[22] Like early Augustine, Pelagians believed that infants would be sent to purgatory.[23] Pelagius emphasized good works and virtue rather than the "self-indulgent cultivation of mystical feelings".[15]

Theologian Carol Harrison commented: "Pelagianism represents an attempt to safeguard God’s justice, to preserve the integrity of human nature as created by God, and of human beings' obligation, responsibility and ability to attain a life of perfect righteousness."[24] However, this is at the expense of downplaying human frailty and presenting "the operation of divine grace as being merely external".[24] Writing to a young girl who had adopted a virgin lifestyle, Pelagius counseled:

The ordering of the perfect life is a formidable matter... to change one’s moral life and to fashion in oneself special virtues of the mind and then to bring them to perfection is a matter which calls for intensive study and long practice. That is why so many of us grow old in the pursuit of this vocation and yet fail to gain the objectives for the sake of which we came to it in the first place.[24]

Defining Pelagianism

What Augustine called "Pelagianism" was more his own invention than that of Pelagius.[18][25] In her study, Bonner found that there was no one individual in who held all the doctrines of "Pelagianism", nor was there a coherent Pelagian movement[25] (although these findings are disputed).[26][27] Bonner argued that the two core ideas promoted by Pelagius were "the goodness of human nature and effective free will" although both were advocated by other Christian authors from the 360s. Because Pelagius did not invent these ideas, she recommended attributing them to the ascetic movement rather than using the word "Pelagian".[25] Later Christians used "Pelagianism" as an insult for theologically orthodox Christians who held positions that they disagreed with. Historian Eric Nelson defined genuine Pelagianism as rejection of original sin or denial of original sin's effect on man's ability to avoid sin.[28]

Comparison of Pelagianism and Augustinianism

Pelagius' teachings on human nature, divine grace, and sin were opposed to those of Augustine, who declared Pelagius "the enemy of the grace of God".[12] Augustine distilled what he called Pelagianism into three heretical tenets: "to think that God redeems according to some scale of human merit; to imagine that some human beings are actually capable of a sinless life; to suppose that the descendants of the first human beings to sin are themselves born innocent".[13] He accused Christians in Gaul who disagreed with him on predestination (but recognized the three Pelagian doctrines as heretical) of being seduced by Pelagian ideas, or what was later called "semi-Pelagianism".[29] Pelagianism shaped Augustine's ideas in opposition to its own on free will, grace, and original sin.[30][31][32] However, according to Peter Brown, "For a sensitive man of the fifth century, Manichaeism, Pelagianism, and the views of Augustine were not as widely separated as we would now see them: they would have appeared to him as points along the great circle of problems raised by the Christian religion".[33] According to Ali Bonner, the crusade against Pelagianism and other heresies narrowed the range of acceptable opinions and reduced the intellectual freedom of classical Rome,[34] and it was Augustine's ideas, not Pelagius', which were novel.[35]

| Belief | Pelagianism | Augustianism |

|---|---|---|

| Original sin | Does not affect human nature[19] | Affects all humans since the Fall[19] |

| Free will | Libertarian free will[12] | Original sin renders men unable to choose good[36] |

| Status of infants | Blameless[22] | Corrupted by original sin[37][19] |

| Sin | Comes about by free choice[19] | Inevitable result of fallen human nature[19] |

| Forgiveness for sin | Given to those who sincerely repent and merit it[lower-alpha 2] | Part of God's grace, disbursed according to his will[38] |

| Sinlessness | Theoretically possible, although unusual[12][21] | Impossible due to the corruption of human nature[37] |

| Salvation | Humans will be judged for their choices alone[12] | Salvation is bestowed by God's grace[39] |

| Predestination | Rejected[40] | God decides who is saved and prevents them from falling away[41] |

According to Nelson, Pelagianism is a solution to the problem of evil that invokes libertarian free will as both the cause of human suffering and a sufficient good to justify it.[42] By positing that man could choose between good and evil without divine intercession, Pelagianism brought into question Christianity's core doctrine of Jesus' act of substitutionary atonement to expiate the sins of mankind.[43] For this reason, Pelagianism became associated with nontrinitarian interpretations of Christianity which rejected the divinity of Jesus,[44] as well as other heresies such as Arianism, Socinianism, and mortalism (which rejected the existence of hell).[28] Augustine argued that if man "could have become just by the law of nature and free will . . . amounts to rendering the cross of Christ void".[42] He argued that no suffering was truly undeserved, and that grace was equally undeserved but bestowed by God's benevolence.[45] Augustine's solution, while it was faithful to orthodox Christology, worsened the problem of evil because according to Augustinian interpretations, God punishes sinners who by their very nature are unable not to sin.[28] The Augustinian defense of God's grace against accusations of arbitrariness is that God's ways are incomprehensible to mere mortals.[28][46] Yet, as later critics such as Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz asserted, asking "it is good and just because God wills it or whether God wills it because it is good and just?", this defense (although accepted by many Catholic and Reformed theologians) creates a God-centered morality, which, in Leibniz' view "would destroy the justice of God" and make him into a tyrant.[47]

Pelagianism and Judaism

One of the most important distinctions between Christianity and Judaism is that the former conventionally teaches justice by faith, while the latter teaches that man has the choice to follow divine law. By teaching the absense of original sin and the idea that humans can choose between good and evil, Pelagianism advocated a position close to that of Judaism.[48] Pelagius wrote positively of Jews and Judaism, recommending that Christians study Old Testament law—a sympathy not commonly encountered in Christianity after Paul.[21] Augustine was the first to accuse Pelagianism of "Judaizing",[49] which became a commonly heard criticism of it.[44][49] However, although contemporary rabbinic literature tends to take a Pelagian perspective on the major questions, and it could be argued that the rabbis shared a Weltanschauung with Pelagius, there were minority opinions within Judaism which argued for ideas more similar to Augustine's.[50] Overall, Jewish discourse did not discuss free will and emphasized God's goodness in his revelation of the Torah.[51]

Later responses

During the Middle Ages, Pelagius' writings were popular but usually attributed to other authors, mainly Augustine and Jerome. According to French scholar Yves-Marie Duval, the Pelagian manuscript On the Christian Life was the second-most copied work (behind Augustine's The City of God) outside of the Bible and liturgical texts.[52][lower-alpha 3]

Thomas Bradwardine (c. 1290–1349) wrote De causa Dei contra Pelagium et de virtute causarum ad suos Mertonenses condemning Pelagianism, as did Gabriel Biel in the 15th century.[10] Johann Pupper, also known as Johannes von Goch (c. 1400–1475), an Augustinian, recommended a return to the text of the Bible as a remedy for Pelagianism.[54]

Early modern era

Pelagianism became a common accusation during the Protestant Reformation; Reformers often used the epithet to critique what they saw as late-medieval Catholicism's undue emphasis on doing good works. Martin Luther (1483–1546), John Calvin (1509–1564), and Cornelius Jansen (1585–1638) reacted in different ways against Pelagianism, and evaluations of Lutheran, Reformed, and Jansenist theologies have often turned on the question of what is or is not Pelagian.[55]

During the modern era, Pelagianism continued to be used as an epithet against orthodox Christians, but there were nevertheless some who had essentially Pelagian views according to Nelson's definition.[28] Nelson argued that many of those considered the predecessors to modern liberalism took Pelagian or Pelagian-adjanect positions on the problem of evil.[56] For instance, Leibniz who coined the word theodicy in 1710, rejected Pelagianism but nevertheless proved to be "a crucial conduit for Pelagian ideas".[57] He argued that "Freedom is deemed necessary in order that man may be deemed guilty and open to punishment."[58] In De doctrina christiana, John Milton argued that "if, because of God’s decree, man could not help but fall . . . then God’s restoration of fallen man was a matter of justice not grace".[59] Milton also argued for other positions that could be considered Pelagian, such as that "The knowledge and survey of vice, is in this world . . . necessary to the constituting of human virtue."[60] Jean-Jacques Rousseau made nearly identical arguments for that point.[60] John Locke argued that the idea that "all Adam’s Posterity [are] doomed to Eternal Infinite Punishment, for the Transgression of Adam" was "little consistent with the Justice or Goodness of the Great and Infinite God".[61] He did not accept that original sin corrupted human nature, and argued that man could live a Christian life (although not "void of slips and falls") and be entitled to justification.[58]

Nelson argues that the drive for rational justification of religion, rather than a symptom of secularization, was actually "a Pelagian response to the theodicy problem" because "the conviction that everything necessary for salvation must be accessible to human reason was yet another inference from God’s justice". In Pelagianism, libertarian free will is necessary but not sufficient for God's punishment of humans to be justified, because man must also understand God's commands.[62] As a result, thinkers such as Locke, Rousseau and Immanuel Kant argued that following natural law without revealed religion must be sufficient for the salvation of those who were never exposed to Christianity because, as Locke pointed out, access to revelation is a matter of moral luck.[63] Early modern proto-liberals such as Milton, Locke, Leibniz, and Rousseau advocated religious toleration and freedom of private action (eventually codified as human rights), as only freely chosen actions could merit salvation.[64][lower-alpha 4]

Nineteenth-century philosopher Søren Kierkegaard dealt with the same problems (nature, grace, freedom, and sin) as Augustine and Pelagius,[37] which he believed were opposites in a Hegelian dialectic.[66] He rarely mentioned Pelagius explicitly[37] even though he inclined towards a Pelagian viewpoint. However, Kierkegaard rejected the idea that man could perfect himself.[67]

Contemporary responses

In the book Guardare Cristo: Esercizi di fede, speranza e carità (Looking at Christ: Exercises of faith, hope and charity),[68] Pope Benedict XVI wrote:

the other face of the same vice is the Pelagianism of the pious. They do not want forgiveness and in general they do not want any real gift from God either. They just want to be in order. They don’t want hope they just want security. Their aim is to gain the right to salvation through a strict practice of religious exercises, through prayers and action. What they lack is humility which is essential in order to love; the humility to receive gifts not just because we deserve it or because of how we act ...

In a June 2013 talk with the leadership of the Religious Confederation of Latin America and the Caribbean (CLAR), Pope Francis alluded to Pelagian tendencies when he referred to "restorationists", one group of whom sent him after his election 3,525 rosaries. The pope said he was "bothered" by this need to count prayers and labeled it "pelagianism." He went on to comment: "these groups return to practices and disciplines I lived – not you, none of you are old – to things that were lived in that moment, but not now, they aren't today ..."[69] The Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith subsequently emphasised "neo-Pelagianism" in a letter of February 2018 titled Placuit Deo, stating, "A new form of Pelagianism is spreading in our days, one in which the individual, understood to be radically autonomous, presumes to save oneself, without recognizing that, at the deepest level of being, he or she derives from God and from others."[70]

John Rawls was a critic of Pelagianism, an attitude that he retained even after becoming an athiest. His anti-Pelagian ideas influenced his book A Theory of Justice, in which he argued that differences in productivity between humans are a result of "moral arbitrariness" and therefore unequal wealth is undeserved.[71] According to Nelson, many contemporary social liberals follow Rawls rather than the older liberal-Pelagian tradition.[72]

References

Notes

- Caelestinus went even further, arguing that Adam had been created mortal.[18]

- Pelagius wrote: "pardon is given to those who repent, not according to the grace and mercy of God, but according to their own merit and effort, who through repentance will have been worthy of mercy".[17]

- At the Council of Diospolis, On the Christian Life was submitted as an example of Pelagius' heretical writings. Scholar Robert F. Evans argues that it was Pelagius' work, but Ali Bonner disagrees.[53]

- This is the opposite of the Augustinian argument against excessive state power, which is that human corruption is such that man cannot be trusted to wield it without creating tyranny, what Judith Shklar called "liberalism of fear".[65]

Citations

- Elliott 2011, p. 377.

- Keech 2012, p. 38.

- Kirwan 1998.

- Wetzel 2001, p. 51.

- Bonner 2004.

- Bonner 2018, p. 270.

- Bonner 2018, p. 299.

- Scheck 2012, p. 79.

- Keech 2012, pp. 39–40.

- Reese 1996, p. 421.

- Keech 2012, p. 40.

- Puchniak 2008, p. 123.

- Wetzel 2001, p. 52.

- Cohen 2016, p. 523.

- Chadwick 2001, p. 116.

- Bonner 2018, pp. 304–305.

- Visotzky 2009, p. 49.

- Visotzky 2009, p. 50.

- Visotzky 2009, p. 44.

- Kirwan 1998, Pelagius.

- Visotzky 2009, p. 48.

- Kirwan 1998, Grace and free will.

- Chadwick 2001, p. 119.

- Harrison 2016, p. 82.

- Bonner 2018, p. 302.

- Chronister 2020, p. 119.

- Lössl 2019, p. 848.

- Nelson 2019, p. 4.

- Wetzel 2001, pp. 52, 55.

- Visotzky 2009, p. 43.

- Keech 2012, p. 15.

- Stump 2001, p. 130.

- Visotzky 2009, p. 53.

- Bonner 2018, pp. 303–304.

- Bonner 2018, p. 305.

- Puchniak 2008, pp. 123–124.

- Puchniak 2008, p. 124.

- Chadwick 2001, pp. 30–31.

- Stump 2001, pp. 139–140.

- Elliott 2011, p. 378.

- Chadwick 2001, pp. 123–124.

- Nelson 2019, p. 3.

- Nelson 2019, pp. 3, 51.

- Nelson 2019, p. 51.

- Chadwick 2001, pp. 117–118.

- Stump 2001, p. 139.

- Nelson 2019, pp. 5–6.

- Fu 2015, p. 182.

- Visotzky 2009, p. 45.

- Visotzky 2009, p. 59.

- Visotzky 2009, p. 60.

- Bonner 2018, pp. 288–289.

- Bonner 2018, Chapter 7, fn 1.

- Webster 1980, p. 783, Johannes von Goch.

- Cottret, Cottret & Michel 2002.

- Nelson 2019, p. 5.

- Nelson 2019, pp. 2, 5.

- Nelson 2019, p. 8.

- Nelson 2019, p. 7.

- Nelson 2019, p. 11.

- Nelson 2019, pp. 7–8.

- Nelson 2019, p. 15.

- Nelson 2019, pp. 16–18.

- Nelson 2019, pp. 19–20.

- Nelson 2019, p. 21.

- Puchniak 2008, p. 126.

- Puchniak 2008, p. 128.

- Ratzinger 1989.

- Winters, Michael Sean (12 June 2013). "Pope Francis on Pelagians, Gnostics and the CDF". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Ladaria, Luis F.; Morandi, Giacomo (22 February 2018). "Letter Placuit Deo to the Bishops of the Catholic Church on Certain Aspects of Christian Salvation". vatican.va. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Nelson 2019, pp. 50, 53.

- Nelson 2019, p. 49.

Sources

- Bonner, Ali (2018). The Myth of Pelagianism. British Academy Monograph. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-726639-7.

- Bonner, Gerald (2004). "Pelagius (fl. c.390–418), theologian". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21784.

- Chadwick, Henry (2001). Augustine: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285452-0.

- Chronister, Andrew C. (2020). "Ali Bonner, The Myth of Pelagianism". Augustinian Studies. 51 (1): 115–119. doi:10.5840/augstudies20205115.

- Cohen, Samuel (2016). "Religious Diversity". In Jonathan J. Arnold; M. Shane Bjornlie; Kristina Sessa (eds.). A Companion to Ostrogothic Italy. Leiden, Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 503–532. ISBN 978-9004-31376-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cottret, Bernard; Cottret, Monique; Michel, Marie-José, eds. (2002). Jansénisme et puritanisme: Actes du colloque du 15 septembre 2001, tenu au Musée National des Granges des Port-Royal-des-Champs [Jansenism and puritanism: Proceedings of the colloquium of 15 September 2001 at the National Museum of Granges des Port-Royal-des-Champs] (in French). Paris: Nolin. Jansénisme et puritanisme at the HathiTrust Digital Library.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Elliott, Mark W. (2011). "Pelagianism". In McFarland, Ian A.; Fergusson, David A. S.; Kilby, Karen; Torrance, Iain R. (eds.). The Cambridge Dictionary of Christian Theology. pp. 377–378. ISBN 978-0-511-78128-5.

- Fu, Youde (2015). "Hebrew Justice: A Reconstruction for Today". The Value of the Particular: Lessons from Judaism and the Modern Jewish Experience. Leiden: Brill. pp. 171–194. ISBN 978-90-04-29269-7.

- Harrison, Carol (2016). "Truth in a Heresy?". The Expository Times. 112 (3): 78–82. doi:10.1177/001452460011200302.

- Keech, Dominic (2012). The Anti-Pelagian Christology of Augustine of Hippo, 396-430. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-966223-4.

- Kirwan, Christopher (1998). "Pelagianism". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Taylor & Francis. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-K064-1.

- Lössl, Josef (20 September 2019). "The myth of Pelagianism. By Ali Bonner. (A British Academy Monograph.) Pp. xviii + 342. Oxford–New York: Oxford University Press (for The British Academy), 2018. £80. 978 0 19 726639 7". The Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 70 (4): 846–849. doi:10.1017/S0022046919001283.

- Nelson, Eric (2019). The Theology of Liberalism: Political Philosophy and the Justice of God. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-24094-0.

- Puchniak, Robert (2008). "Pelagius: Kierkegaard's use of Pelagius and Pelagianism". In Stewart, Jon Bartley (ed.). Kierkegaard and the Patristic and Medieval Traditions. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7546-6391-1.

- Ratzinger, Joseph (1989). Guardare Cristo: esercisi di fede, speranza e carità [Looking at Christ: Exercises of faith, hope and charity] (in Italian). Editoriale Jaca. ISBN 978-88-16-30178-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reese, William L. (1996). Dictionary of Philosophy and Religion: Eastern and Western Thought. Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-621-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scheck, Thomas P. (2012). "Pelagius's Interpretation of Romans". In Cartwright, Steven (ed.). A Companion to St. Paul in the Middle Ages. Leiden: Brill. pp. 79–114. ISBN 978-90-04-23671-4.

- Stump, Eleonore (2001). "Augustine on free will". In Stump, Eleonore; Kretzmann, Norman (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Augustine. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 124–147. ISBN 978-1-1391-7804-4.

- Tornielli, Andrea (June 12, 2013). "Francis, Ratzinger and the Pelagianism risk". Vatican Insider/La Stampa. Archived from the original on 2017-02-13.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Visotzky, Burton L. (2009). "Will and Grace: Aspects of Judaising in Pelagianism in Light of Rabbinic and Patristic Exegesis of Genesis". In Grypeou, Emmanouela; Spurling, Helen (eds.). The Exegetical Encounter Between Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity. Leiden: Brill. pp. 43–62. ISBN 978-90-04-17727-7.

- Wetzel, James (2001). "Predestination, Pelagianism, and foreknowledge". In Stump, Eleonore; Kretzmann, Norman (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Augustine. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 49–58. ISBN 978-1-1391-7804-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Cyr, Taylor W.; Flummer, Matthew T. (2018). "Free will, grace, and anti-Pelagianism". International Journal for Philosophy of Religion. 83 (2): 183–199. doi:10.1007/s11153-017-9627-0. ISSN 1572-8684.

- Marcus, Gilbert (2005). "Pelagianism and the 'Common Celtic Church'" (PDF). Innes Review. 56 (2): 165–213.

- Rackett, Michael R. (2002). "What's Wrong with Pelagianism?". Augustinian Studies. 33 (2): 223–237. doi:10.5840/augstudies200233216.

- Rees, Brinley Roderick (1988). Pelagius: A Reluctant Heretic. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 0851155030.

- Rees, Brinley Roderick (1998). Pelagius: Life and Letters. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85115-714-6.

- Squires, Stuart (2013). Philip Rousseau (ed.). Reassessing Pelagianism: Augustine, Cassian, and Jerome on the Possibility of a Sinless Life (PhD thesis). Catholic University of America.

- Squires, Stuart (2019). The Pelagian Controversy: An Introduction to the Enemies of Grace and the Conspiracy of Lost Souls. Eugene: Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-5326-3781-0.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Pelagianism |

- Pelagius Library: Online site dedicated to the study of Pelagius