SpaceX South Texas Launch Site

The SpaceX South Texas Launch Site is a rocket production facility, test site, and spaceport near Brownsville, Texas, on the US Gulf Coast approximately 22 miles (35 km) east of Brownsville, Texas, for the private use of SpaceX.[1][2][3] When conceptualized, its stated purpose was "to provide SpaceX an exclusive launch site that would allow the company to accommodate its launch manifest and meet tight launch windows."[4] The launch site was originally intended to support launches of the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy launch vehicles as well as "a variety of reusable suborbital launch vehicles",[4] but in 2018, SpaceX announced a change of plans, stating that the launch site would be used exclusively for SpaceX's next-generation launch vehicle, Starship.[5] In 2019 and 2020, the site added significant rocket production and test capacity. SpaceX CEO Elon Musk indicated in 2014 that he expected "commercial astronauts, private astronauts, to be departing from South Texas,"[6] and he foresaw launching spacecraft to Mars from there.[7]

Regional location of the SpaceX Texas launch facility, from the FAA draft EIS, April 2013 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Brownsville, Cameron County, Texas, United States | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operator | SpaceX | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Between 2012 and 2014, SpaceX considered seven potential locations around the United States for the new commercial launch facility. For much of this period, a parcel of land adjacent to Boca Chica Beach near Brownsville, Texas, was the leading candidate location, during an extended period while the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) conducted an extensive environmental assessment on the use of the Texas location as a launch site. Also during this period, SpaceX began acquiring land in the area, purchasing approximately 41 acres (170,000 m2) and leasing 57 acres (230,000 m2) by July 2014. SpaceX announced in August 2014, that they had selected the location near Brownsville as the location for the new non-governmental launch site,[8] after the final environmental assessment completed and environmental agreements were in place by July 2014.[9][10][11] When completed, it will become SpaceX's fourth active launch facility, following three launch locations that are leased from the US government.

SpaceX conducted a groundbreaking ceremony on the new launch facility in September 2014,[12][6] and soil preparation began in October 2015.[13][14] The first tracking antenna was installed in August 2016, and the first propellant tank arrived in July 2018. In late 2018, construction ramped up considerably, and the site saw the fabrication of the first 30 ft-diameter (9 m) prototype test vehicle, Starhopper, which was tested and flown March–August 2019. Through 2019 and 2020, additional prototype flight vehicles are being built at the facility for higher-altitude tests in 2020. By March 2020, there were over 500 people employed at the facility, with most of the work force involved in 24/7 production operations for the second-generation SpaceX launch vehicle, Starship.

History

Private discussions between SpaceX and various state officials about a future private launch site began at least as early as 2011,[15] and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk mentioned interest in a private launch site for their commercial launches in a speech in September 2011.[16] The company publicly announced in August 2014, that they had decided on Texas as the location for their new non-governmental launch site.[8] Site soil work began in 2015 but major construction of facilities began only in late 2018, with rocket engine testing with flight testing beginning in 2019.

Launch site selection and environmental assessment

As early as April 2012, at least five potential locations were publicly known, including "sites in Alaska, California, Florida,[17] Texas and Virginia."[18] In September 2012, it became clear that Georgia and Puerto Rico were also interested in pursuing the new SpaceX commercial spaceport facility.[19] The Camden County, Georgia, Joint Development Authority voted unanimously in November 2012 to "explore developing an aero-spaceport facility" at an Atlantic coastal site to support both horizontal and vertical launch operations.[20] The main Puerto Rico site under consideration at the time was land that had formerly been the Roosevelt Roads Naval Station.[4]:87 By September 2012, SpaceX was considering a total of seven potential locations for the new commercial launch pad around the United States. For much of the time since, the leading candidate location for the new facility was a parcel of land adjacent to Boca Chica Beach near Brownsville, Texas.

By early 2013, Texas remained the leading candidate for the location of the new SpaceX commercial launch facility, although Florida, Georgia and other locations also remained in the running. Legislation was introduced in the Texas Legislature to enable temporary closings of State beaches during launches, limit liability for noise and some other specific commercial spaceflight risks, as well as considering a package of incentives to encourage SpaceX to locate at the Brownsville, Texas location.[21][22] 2013 economic estimates showed SpaceX investing approximately US$100 million in the development and construction of the facility[22] A US$15 million incentive package was approved by the Texas Legislature in 2013.[23]

From the beginning, one of the proposed locations for the new commercial-mission-only[4] spaceport had been south Texas. In April 2012, the FAA's Office of Commercial Space Transportation initiated a Notice of Intent to conduct an Environmental Impact Statement[24] and public hearings on the new launch site, which would be located in Cameron County, Texas. The summary then indicated that the Texas site would support up to 12 commercial launches per year, including two Falcon Heavy launches.[25][26][18] The first public meeting was held in May 2012,[26][27] and the FAA released a draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the location in south Texas in April 2013. Public hearings on the draft EIS occurred in Brownsville, followed by a public comment period ending in June 2013.[28][29][30] The draft EIS identified three parcels of land—total of 12.4 acres (5.0 ha)—that would notionally be used for the control center. In addition, SpaceX had leased 56.6 acres (22.9 ha) of land adjacent to the terminus of Texas State Highway 4, 20 acres (8.1 ha) of which would be used to develop the vertical launch area; the remainder would remain open space surrounding the launch facility.[4] In July 2014, the FAA officially issued its Record of Decision concerning the Boca Chica Beach facility, and found that "the proposal by Elon Musk’s Space Exploration Technologies would have no significant impact on the environment,"[31] approving the proposal and outlining SpaceX's proposal.[31] The company formally announced selection of the Texas location in August 2014.[8]

In September 2013, the State of Texas General Land Office (GLO) and Cameron County signed an agreement outlining how beach closures would be handled in order to support a future SpaceX launch schedule. The agreement is intended to enable both economic development in Cameron County and protect the public's right to have access to Texas state beaches. Under the 2013 Texas plan, beach closures would be allowed but were not expected to exceed a maximum of 15 hours per closure date, with no more than three scheduled space flights between the Saturday prior to Memorial Day and Labor Day, unless the Texas GLO approves.[30]

In 2019, the FAA completed a reevaluation of the SpaceX facilities in South Texas, and in particular the revised plans away from a commercial spaceport to more of a spaceship yard for building and testing rockets at the facility, as well as flying different rockets—SpaceX Starship and prototype test vehicles—from the site than the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy envisioned in the original 2014 environmental assessment.[32] In May and August 2019, the FAA issued a written report with a decision that a new supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) would not be required.[33][34]

Land acquisition

Prior to a final decision on the location of the spaceport, SpaceX began purchasing a number of real estate properties in Cameron County, Texas beginning in June 2012.[28] By July 2014, SpaceX had purchased approximately 41 acres (170,000 m2) and leased 57 acres (230,000 m2) near Boca Chica Village and Boca Chica Beach[35] through a company named Dogleg Park LLC, a reference to the type of trajectory that rockets launched from Boca Chica will be required to follow.[36]

Prior to May 2013, five lots in the Spanish Dagger Subdivision in Boca Chica Village, adjacent to Highway 4 which leads to the proposed launch site, had been purchased. In May 2013, SpaceX purchased an additional three parcels, adding another 1 acre (4,000 m2),[28] plus four more lots with a total of 1.9 acres (7,700 m2) in July 2013, making a total of 12 SpaceX-purchased lots.[23] In November 2013, SpaceX substantially "increased its land holdings in the Boca Chica Beach area from 12 lots to 72 undeveloped lots" purchased, which encompass a total of approximately 24 acres (97,000 m2), in addition to the 56.5 acres (229,000 m2) leased from private property owners.[29] An additional few acres were purchased late in 2013, raising the SpaceX total "from 72 undeveloped lots to 80 lots totaling about 26 acres."[37] In late 2013, SpaceX completed a replat of 13 lots totaling 8.3 acres (34,000 m2) into a subdivision that they have named "Mars Crossing."[38][39]

In February 2014, they purchased 28 additional lots that surround the proposed complex at Boca Chica Beach, raising the SpaceX-owned land to approximately 36 acres (150,000 m2) in addition to the 56-acre (230,000 m2) lease.[38] SpaceX's investments in Cameron County continued in March 2014, with the purchase of more tracts of land, bringing the total number of lots it now owns to 90. Public records showed that the total land area that SpaceX then owned through Dogleg Park LLC was roughly 37 acres (150,000 m2). This is in addition to 56.5 acres (229,000 m2) that SpaceX then had under lease.[40] By September 2014, Dogleg Park completed a replat of lots totaling 49.3 acres (200,000 m2) into a second subdivision, this one named "Launch Site Texas", made up of several parcels of property previously purchased. This is the site of the launch site itself while the launch control facility is planned two miles west in the Mars Crossing subdivision. Dogleg Park has also continued purchasing land in Boca Chica, and now owns a total of "87 lots equaling more than 100 acres".[39]

SpaceX has also bought and is modifying several residential properties in Boca Chica Village, but apparently planning to leave them in residential use, about 2 miles (3.2 km) west of the launch site.[41]

In September 2019, SpaceX extended an offer to buy each of the houses in Boca Chica Village for three times the fair market value along with an offer of VIP invitations to future launch events. The 3x offer was said to be "non-negotiable." Homeowners were given two weeks for this particular offer to remain valid.[42]

Construction

Major site construction at SpaceX's launch site in Boca Chica got underway in 2016, with site soil preparation for the launch pad in a process said to take two years, with significant additional soil work and significant construction beginning in late 2018. By September 2019, the site had been "transformed into an operational launch site – outfitted with the ground support equipment needed to support test flights of the methane-fueled Starship vehicles."[43] Lighter construction of fencing and temporary buildings in the control center area had begun in 2014.[39][44]

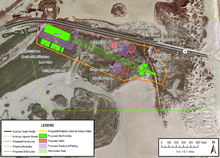

The Texas launch location was projected in the 2013 draft EIS to include a 20 acres (81,000 m2) vertical launch area and a 12.2 acres (49,000 m2) area for a launch control center and a launch pad directly adjacent to the eastern terminus of Texas State Highway 4.[4] Changes occurred based on actual land SpaceX was able to purchase and replat for the control center and primary spaceship build yard.

SpaceX broke ground on the new launch site in September 2014,[12] but indicated then that the principal work to build the facility was not expected to ramp up until late 2015[6] after the SpaceX launch site development team completed work on Kennedy Space Center Launch Pad 39A, as the same team was expected to manage the work to build the Boca Chica facility. Advance preparation work was expected to commence ahead of that. As of 2014, SpaceX anticipated spending approximately US$100 million over three to four years to build the Texas facility, while the Texas state government expected to spend US$15 million to extend utilities and infrastructure to support the new spaceport.[6] The design phase for the facility was completed by March 2015.[45] In the event, construction was delayed by the destruction of one of SpaceX two Florida launch facilities in a September 2016 rocket explosion, which tied up the launch site design/build team for over a year.

In order to stabilize the waterlogged ground at the coastal site, SpaceX engineers determined that a process known as soil surcharging would be required. For this to happen, some 310,000 cubic yards (240,000 m3) of new soil was trucked to the facility between October 2015 and January 2016.[13][46] In January 2016, following additional soil testing that revealed foundation problems, SpaceX indicated they were not planning to complete construction until 2017, and the first launch from Boca Chica was not expected until late 2018.[14][46][47] In February 2016, SpaceX President and COO Gwynne Shotwell stated that construction had been delayed by poor soil stability at the site, and that "two years of dirt work" would be required before SpaceX could build the launch facility, with construction costs expected to be higher than previously estimated.[48] The first phase of the soil stabilization process was completed by May 2016.[49]

Two 30 ft (9 m) S-band tracking station antennas , were installed at the site in 2016–2017,[50] Formerly used to track the Space Shuttle during launch and landing,[51][52] and made operational as tracking resources for manned Dragon missions in 2018.

A SpaceX-owned 6.5-acre (26,000 m2) photovoltaic power station was installed on site to provide off-grid electrical power near the control center,[11][53][54] The solar farm was installed by SolarCity in January 2018.

Progress on building the pad had slowed considerably through 2017, much slower than either SpaceX or Texas state officials had expected when it was announced in 2014. Support for SpaceX, however, remained fairly strong amongst Texas public officials.[50] In January 2018, COO Shotwell said the pad might be used for "early vehicle testing" by late 2018 or early 2019 but that additional work would be required after that to make it into a full launch site.[55] SpaceX achieved this new target, with prototype rocket and rocket engine ground testing at Boca Chica starting in March 2019, and suborbital flight tests starting in July 2019.

In late 2018, construction ramped up considerably, and the site saw the development of a large propellant tank farm, a gas flare, more offices, and a small flat square launch pad. The Starhopper prototype was relocated to the pad in March 2019, and first flew in late July 2019.[56]

In late 2018, the "Mars Crossing" subdivision developed into a shipyard, with the development of several large hangars, and several concrete jigs, on top of which large steel rocket airframes were fabricated, the first of which became the Starhopper test article. In February 2019, SpaceX confirmed that the first orbit-capable Starship and Super Heavy test articles would be manufactured nearby, at the "SpaceX South Texas build site."[57] By September 2019, the facility had been completely transformed into a new phase of an industrial rocket build facility, working multiple shifts and more than five days a week, able to support large rocket ground and flight testing.[43] As of November 2019 the SpaceX south Texas Launch Site crew has been working on a new launch pad for its Starship/Super Heavy rocket; the former launch site has been transformed to an assembly site for the Starship rocket.[58]

Operation

The South Texas Launch Site is SpaceX's fourth active suborbital launch facility, and its first private facility. As of 2019, SpaceX leased three US government-owned launch sites: Vandenberg SLC 4 in California, and Cape Canaveral SLC-40 and Kennedy Space Center LC39A both in Florida.

The launch site is in Cameron County, Texas,[21] approximately 17 miles (27 km) east of Brownsville, with launch flyover range over the Gulf of Mexico.[4] The launch site is planned to be optimized for commercial activity, as well as used to fly spacecraft on interplanetary trajectories.[7]

Launches on orbital trajectories from Brownsville will have a constrained flight path, due to the Caribbean Islands as well as the large number of Oil platforms in the Gulf of Mexico. SpaceX has stated that they have a good flight path available for the launching of satellites on trajectories toward the commercially valuable geosynchronous orbit.[59]

Although SpaceX initial plans for the Boca Chica launch site are to loft robotic spacecraft to geosynchronous orbits, Elon Musk indicated in September 2014 that "the first person to go to another planet could launch from [the Boca Chica launch site]",[60] but did not indicate which launch vehicle might be used for those launches. In May 2018, Elon Musk clarified that the South Texas launch site will be used exclusively for Starship.[5]

By March 2019, two test articles of Starship were being built, and three by May.[61] The low-altitude, low-velocity Starship test flight rocket was used for initial integrated testing of the Raptor rocket engine with a flight-capable propellant structure, and was slated to also test the newly designed autogenous pressurization system that is replacing traditional helium tank pressurization as well as initial launch and landing algorithms for the much larger 9-metre-diameter (29 ft 6 in) rocket.[62] SpaceX originally developed their reusable booster technology for the 3-meter-diameter Falcon 9 from 2012 to 2018. The Starhopper prototype was also the platform for the first flight tests of the full-flow staged combustion methalox Raptor engine, where the hopper vehicle was flight tested with a single engine in July/August 2019,[63] but could be fitted with up to three engines to facilitate engine-out tolerance testing.[62]

By March 2020, SpaceX had doubled the number of employees onsite for Starship manufacturing, test and operations since January, with over 500 employees working at the site. Four shifts are working 24/7—in 12-hour shifts with 4 days on then 3 off followed by 3 days on and 4 off—to enable continuous Starship manufacturing with workers and equipment specialized to each task of serial Starship production.[58]

Social and economic impact

The new launch facility was projected in a 2014 study to generate US$85 million of economic activity in the city of Brownsville and eventually generate approximately US$51 million in annual salaries from some 500 jobs projected to be created by 2024.[64]

A local economic development board was created for south Texas in 2014—the Cameron County Space Port Development Corporation (CCSPDC)—in order to facilitate the development of the aerospace industry in Cameron County near Brownsville. The first project for the newly established board is the SpaceX project to develop a launch site at Boca Chica Beach.[65] In May 2015, Cameron County transferred ownership of 25 lots in Boca Chica to CCSPDC, which may be used to develop event parking.[66]

Effects on nearby homeowners

The launch facility was approved to be constructed two miles from approximately thirty homes, with no indication that this would cause problems for the homeowners. Five years later in 2019, following an FAA revaluation of the environmental impact[32] and the issuance of new FAA requirements that residents be asked to voluntarily stay outside their houses during particular tanking and engine ignition tests, SpaceX decided that a couple dozen of these homes were now too close to the launch facility over the long term and began seeking market acquisition of these properties.[67] It was not disclosed why SpaceX did not seek a more remote location for its launch facility at the outset of their location search, or if SpaceX did in fact know in 2014 that it would eventually seek to displace these homeowners. Use of eminent domain to acquire the properties has not been ruled out. It was not known if the two dozen homes would be enough to satisfy SpaceX, or if eventually SpaceX would seek to rid the entire area of homes. An attorney with expertise on such situations referred to the timeframe given by SpaceX for homeowners to consider their purchase offer as "aggressive".[68]

Research facilities

The Brownsville Economic Development Council (BEDC) is building a space tracking facility in Boca Chica Village on a 2.3-acre (9,300 m2) site adjacent to the SpaceX launch control center. The STARGATE tracking facility is a joint project of the BEDC, SpaceX, and the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley (formerly the University of Texas at Brownsville at the time the agreement was reached).[39]

Tourism

In January 2016, the South Padre Island Convention and Visitors Advisory Board (CVA) recommended that the South Padre Island City Council "proceed with further planning regarding potential SpaceX viewing sites."[69]

See also

- List of spaceports

- SpaceX reusable launch system development program

References

- "Capabilities & Services". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- Berger, Eric (5 August 2014). "Texas, SpaceX announce spaceport deal near Brownsville". MySanAntonio.com. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- Shotwell, Gwynne (17 March 2015). "Statement of Gwynne Shotwell, President & Chief Operating Officer, Space Exploration Technologies Corp. (SpaceX)" (PDF). U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Armed Services Subcommittee on Strategic Forces. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

SpaceX is developing an additional private launch facility in South Texas to support our commercial launch service contracts.

- Nield, George C.; et al. (Office of Commercial Space Transportation) (April 2014). "Volume I, Executive Summary and Chapters 1–14". Draft Environmental Impact Statement: SpaceX Texas Launch Site (PDF) (Report). Federal Aviation Administration. HQ-0092-K2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2013.

- Gleeson, James; Musk, Elon; et al. (10 May 2018). "Block 5 Phone Presser". GitHubGist. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

Our South Texas launch site will be dedicated to BFR, because we get enough capacity with two launch complexes at Cape Canaveral and one at Vandenberg to handle all of the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy missions.

- Foust, Jeff (22 September 2014). "SpaceX Breaks Ground on Texas Spaceport". SpaceNews. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

Under that development schedule, Musk said, the first launch from the Texas site could take place as soon as late 2016.

- Clark, Steve (27 September 2014). "SpaceX chief: Commercial launch sites necessary step to Mars". Brownsville Herald. Archived from the original on 18 May 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- Berger, Eric (4 August 2014). "Texas, SpaceX announce spaceport deal near Brownsville". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- "Elon Musk's Futuristic Spaceport Is Coming to Texas". Bloomberg Businessweek. 16 July 2014. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- Klotz, Irene (11 July 2014). "FAA Ruling Clears Path for SpaceX Launch site in Texas". Space News. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- Perez-Treviño, Emma (29 July 2014). "SpaceX, BEDC request building permits". Brownsville Herald. Archived from the original on 13 January 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- "SpaceX breaks ground at Boca Chica beach". Brownsville Herald. 22 September 2014. Archived from the original on 12 June 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- Perez-Treviño, Emma (22 October 2015). "Soil headed to Boca Chica for SpaceX". Valley Morning Star. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- "Foundation Problems Delay SpaceX Launch". KRGV.com/5news. Rio Grande Valley, Texas. 18 January 2016. Archived from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

SpaceX’s first launch was set for 2017. The company said the launch site won’t be complete until 2017. They anticipate their first launch in 2018.

- "Texas tries to woo SpaceX on launches". Daily News. 12 February 2014. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- Mark Hamrick, Elon Musk (29 September 2011). National Press Club: The Future of Human Spaceflight. NPC video repository (video). National Press Club. Event occurs at 32:30. Archived from the original on 15 May 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- Dean, James (3 April 2013). "Proposed Shiloh launch complex at KSC debated in Volusia". Florida Today. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- "Details Emerge on SpaceX's Proposed Texas Launch Site". Space News. 16 April 2012. p. 24.

SpaceX is considering multiple potential locations around the country for a new commercial launch pad. ... The Brownsville area is one of the possibilities.

- Perez-Treviño, Emma (13 September 2012). "Sanchez: Texas offering $6M, Florida giving $10M". Brownsville Herald. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- Dickson, Terry (16 November 2012). "Camden County wants to open Georgia's first spaceport". The Florida Times-Union. Archived from the original on 11 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- Foust, Jeff (1 April 2013). "The great state space race". The Space Review. Archived from the original on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

In the best-case scenario, he said, SpaceX would start construction of the spaceport next year, and the first launches from the new facility would take place in two to three years.

- Nelson, Aaron M. (5 May 2013). "Brownsville leading SpaceX sweepstakes?". MySanAntonio.com. Archived from the original on 6 May 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- Perez-Treviño, Emma (15 August 2013). "SpaceX buys more land". Valley Morning Star. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- "FAA Notice of Intent to conduct an Environmental Impact Statement" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. 3 April 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- "SpaceX Proposes New Texas Launch Site". Citizens in Space. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013.

- Martinez, Laura (10 April 2012). "Brownsville area candidate for spaceport". The Monitor. Archived from the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Berger, Eric (25 May 2012). "Texas reaches out to land spaceport deal with SpaceX". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- Perez-Treviño, Emma (20 June 2013). "SpaceX buys more land here". Valley Morning Star. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- Perez-Treviño, Emma (23 November 2013). "SpaceX buys more land in Cameron County". Valley Morning Star. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- Martinez, Laura B. (19 September 2013). "SpaceX beach closure rules set". Brownsville Herald. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- Perez-Treviño, Emma (9 July 2014). "FAA approves SpaceX application to launch rockets from Cameron County beach". The Monitor. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- Mosher, Dave (5 September 2019). "New documents reveal SpaceX's plans for launching Mars-rocket prototypes from South Texas". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

The new assessment covers SpaceX's shift away from developing a commercial spaceport and confronts its new reality as a skunkworks for Starship.

-

"WRITTEN RE-EVALUATION OF THE 2014 FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT FOR THE SPACEX TEXAS LAUNCH SITE" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. 21 May 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

the FAA has concluded that the issuance of launch licenses and/or experimental permits to SpaceX to conduct Starship tests (wet dress rehearsals, static engine fires, small hops, and medium hops) conforms to the prior environmental documentation, that the data contained in the 2014 EIS remain substantially valid, that there are no significant environmental changes, and that all pertinent conditions and requirements of the prior approval have been met or will be met in the current action. Therefore, the preparation of a supplemental or new environmental document is not necessary.

-

"ADDENDUM TO THE 2019 WRITTEN RE-EVALUATION FOR SPACEX'S REUSABLE LAUNCH VEHICLE EXPERIMENTAL TEST PROGRAM AT THE SPACEX LAUNCH SITE" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. 21 August 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

The proposed experimental test program has progressed to the extent that further operational details can be provided and considered within the context of the 2014 Final Environmental Impact Statement for the SpaceX Texas Launch Site (2014 ElS). This addendum re-evaluates the potential environmental consequences of the updated operational details within the context of the 2014 ElS.

- Perez-Treviño, Emma (24 May 2014). "SpaceX buys land". Valley Morning Star. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- Perez-Treviño, Emma (19 August 2013). "Cameron County closes two streets for SpaceX". Brownsville Herald. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- Perez-Treviño, Emma (6 January 2014). "SpaceX buys more Cameron County land". Brownsville Herald. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- Perez-Treviño, Emma (19 February 2014). "SpaceX continues local land purchases". Valley Morning Star. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- Perez-Treviño, Emma (25 September 2014). "SpaceX makes more moves". Valley Morning Star. Archived from the original on 27 September 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- "SpaceX still buying land". Valley Morning Star.

- "The New Residents: Renovation planned for house linked to SpaceX". Valley Morning Star. 29 August 2014. Archived from the original on 24 December 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- "SpaceX launch pad transforms tiny Texas neighborhood: "Where the hell do I go now?"". CBS News. 18 September 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- Baylor, Michael (21 September 2019). "Elon Musk's upcoming Starship presentation to mark 12 months of rapid progress". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

at SpaceX’s launch site in Boca Chica, there was not much more than a mound of dirt [in September 2018 but one year later] the mound of dirt has been transformed into an operational launch site – outfitted with the ground support equipment needed to support test flights of the methane-fueled Starship vehicles.

- Clark, Steve (4 February 2015). "SpaceX vendor fairs slated". The Monitor. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- Perez-Treviño, Emma (14 March 2015). "SpaceX prepping for construction". Valley Morning Star. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- Huertas, Tiffany (11 February 2016). "SpaceX working to stabilize land at rocket launch site". CBS4 ValleyCentral.com. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Clark, Stephen (6 September 2016). "SpaceX may turn to other launch pads when rocket flights resume". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 9 September 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- Foust, Jeff (4 February 2014). "SpaceX seeks to accelerate Falcon 9 production and launch rates this year". SpaceNews. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Huertas, Tiffany (18 May 2016). "SpaceX construction causing problems for surrounding residents". ValleyCentral.com / KGBT-TV. Archived from the original on 14 June 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- Bob Sechler (22 November 2017). "Progress slow at SpaceX's planned spaceport". WSB-TV 2. Archived from the original on 6 January 2018. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- Clark, Steve (13 August 2016). "SpaceX moving two giant antennas to Boca Chica". Brownsville Herald.

- Pearlman, Robert Z. (2 August 2011). "NASA Closes Historic Antenna Station That Tracked Every Space Shuttle Launch". Space.com News. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- Perez-Treviño, Emma (6 August 2015). "Solar project planned for SpaceX". Valley Morning Star. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- Swanner, Nate (7 August 2014). "SpaceX launch facility goes green, will have solar panel field". Slash Gear. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Rumbaugh, Andrea (11 January 2018). "Aerospace talent in Texas lauded". Houston Chronicle.

SpaceX has a rocket engine testing facility in McGregor and is building a launch site in Boca Chica, said Gwynne Shotwell, president and chief operating officer of SpaceX. The latter project, she said, will be ready late this year or early next year for early vehicle testing. SpaceX will then continue working toward making it a launch site.

- Burghardt, Thomas (25 July 2019). "Starhopper successfully conducts debut Boca Chica Hop". NasaSpaceflight.com. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- Ralph, Eric (16 February 2019). "SpaceX job posts confirm Starship's Super Heavy booster will be built in Texas". Teslarati. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

fabricators will work to build the primary airframe of the Starship and Super Heavy vehicles at the SpaceX South Texas build site. [They] will work with an elite team of other fabricators and technicians to rapidly build the tank (cylindrical structure), tank bulkheads, and other large associated structures for the flight article design of both vehicles.

- Berger, Eric (5 March 2020). "Inside Elon Musk's plan to build one Starship a week—and settle Mars". Ars Technica. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- Gwynne Shotwell (21 March 2014). Broadcast 2212: Special Edition, interview with Gwynne Shotwell (audio file). The Space Show. Event occurs at 03:00–04:05. 2212. Archived from the original (mp3) on 22 March 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

we are threading the needle a bit, both with the islands as well as the oil rigs, but it is still a good flight path to get commercial satellites to GEO.

- Solomon, Dan (23 September 2014). "SpaceX Plans To Send People From Brownsville To Mars in Order To Save Mankind". TexasMonthly. Archived from the original on 28 September 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Baylor, Michael (17 May 2019). "SpaceX considering SSTO Starship launches from Pad 39A". NASASpaceFlight. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- Gebhardt, Chris (3 April 2019). "Starhopper conducts Raptor Static Fire tests". NASASpaceFlight. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Burghardt, Thomas (25 July 2019). "Starhopper successfully conducts debut Boca Chica Hop". NASASpaceFlight. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Jervis, Rick (6 October 2014). "Texas border town to become next Cape Canaveral". USA Today. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- Long, Gary (30 July 2014). "Board meets regarding SpaceX project". Brownsville Herald. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- Perez-Treviño, Emma (10 May 2015). "Expanding the future". Valley Morning Star. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- Flahive, Paul (26 September 2019). "SpaceX Squares Off Against Homeowners Near Texas Launch Facility". All Things Considered. National Public Radio. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- Masunaga, Samantha (1 October 2019). "To reach Mars, SpaceX is trying to buy up a tiny Texas community". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- Kunkle, Abbey (15 January 2016). "City moves forward with viewing facility". Port Isabel-South Padre Press. Archived from the original on 20 January 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to SpaceX South Texas Launch Site. |

- SpaceX gets preliminary FAA nod for South Texas launch site, Waco Tribune-Herald, 16 April 2013.

- Lone Star State Bets Heavily on a Space Economy, New York Times, 27 November 2014.