Shina language

Shina (ݜݨیاٗ = ݜݨیاٗ = Šiṇyaá) is a language from the Dardic sub-group of the Indo-Aryan family spoken by the Shina people, a plurality of the people in Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan, as well as in pockets in Jammu and Kashmir, India such as in Dah Hanu, Gurez and Dras.[6][7]

| Shina | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Pakistan, India |

| Region | Gilgit-Baltistan, Chitral, Gurais, Dras, Dah Hanu |

| Ethnicity | Shina |

Native speakers | 600,000 in Pakistan Total users in all countries: 644,200. Shina Kohistani 401,000[1] (2016)[2] |

| Arabic script (Nastaʿlīq)[3] | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:scl – Shinaplk – Kohistani Shina |

| Glottolog | shin1264 Shina[4]kohi1248 Kohistani Shina[5] |

| |

Until recently, there was no writing system of the language. A number of schemes have been proposed and there is no single writing system used by all of the speakers of Shina language.[8]

Dialects

In India, the dialects of the Shina language have preserved both initial and final OIA consonant clusters, while the Shina dialects spoken in Pakistan have not.[9]

Dialects of the Shina language are Gilgiti (the prestige dialect), Astori, Chilasi Kohistani, Drasi, Gurezi, Jalkoti, Kolai, and Palasi. Related languages spoken by ethnic Shina are Brokskat (the Shina of Baltistan and Dras), Kohistani Shina, Palula, Savi, and Ushojo.[7]

Geography

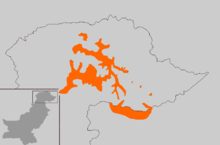

Shina is spoken in various parts of the Kashmir region shared between India and Pakistan. The valleys in which it is spoken include Nagar Shinaki (including Shainbar to Pisan), Southern Hunza, Astore, Chilas, Darel, Tangir, Gilgit, Danyor, Oshikhandass, Jalalabad, Haramosh, Bagrote, Ghizer, Gurez, Dras, Gultari Valley, Skardu, Sadpara, Juglot, some areas of Roundu district of Baltistan including Ganji Valley, Chamachoo, Shengus, Sabsar, Yulboo, Tallu, Tallu-Broq, Tormik, some areas of Kharmang district of Baltistan like Duru Village, Tarkati, Ingutt and Brechil and Palas and Kolai in Kohistan.

Writing

Shina is one of the few Dardic languages with a written tradition.[10] However, it was an unwritten language until a few decades ago[11] and there still is not a standard orthography.[12] Since the first attempts at accurately representing Shina's phonology in the 1960s there have been several proposed orthographies for the different varieties of the language, with debates centering on whether vowel length and tone should be represented.[13] For the Drasi variety spoken in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir, there have been two proposed schemes, one with the Perso-Arabic script and the other with the Devanagari script.[14]

As such, Shina is written with a variation of the Urdu alphabet. The additional letters to write Shina are:

Phonology

The following is a description of the phonology of the Drasi variety spoken in India.

Vowels

The Shina principal vowel sounds:[15]

| Front | Mid | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||

| High | i | u | ||

| Lower high | e | o | ||

| Higher low | ɛ | ə | ʌ | ɔ |

| Low | a | |||

All vowels but /ɔ/ can be either long or nasalized, though no minimal pairs with the contrast are found.[15]

Diphthongs

In Shina there are the following diphthongs:[16]

- falling: ae̯, ao̯, eə̯, ɛi̯, ɛːi̯, ue̯, ui̯, oi̯, oə̯;

- falling nasalized: ãi̯, ẽi̯, ũi̯, ĩũ̯, ʌĩ̯;

- raising: u̯i, u̯e, a̯a, u̯u.

Consonants

| Labial | Coronal | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | Plain | p | t | ʈ | k | ||

| Aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | ʈʰ | kʰ | |||

| Voiced | b | d | ɖ | ɡ | |||

| Affricate | Plain | ts | tʂ | tʃ | |||

| Aspirated | tsʰ | tʂʰ | tʃʰ | ||||

| Voiced | dz[lower-alpha 1] | dʒ[lower-alpha 1] | |||||

| Fricative | Plain | (f) | s | ʂ | ʃ | x[lower-alpha 1] | h |

| Voiced | z | ʐ | ʒ[lower-alpha 1] | ɣ[lower-alpha 1] | ɦ[lower-alpha 1] | ||

| Nasal | m | n | ɳ | ŋ | |||

| Lateral | l | ||||||

| Rhotic | r | ɽ[lower-alpha 2] | |||||

| Semivowel | ʋ~w | j | |||||

- According to Rajapurohit (2012, p. 33–34)

- Degener (2008, p. 14) lists it as a phoneme

Tone

Shina words are often distinguished by three contrasting tones: level, rising, and falling tones. Here is an example that shows the three tones:

"The" has a level tone and means the imperative "Do!"

When the stress falls on the first mora of a long vowel, the tone is falling. Thée means "Will you do?"

When the stress falls on the second mora of a long vowel, the tone is rising. Theé means "after having done".

See also

References

- "ethnologue".

- Shina at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Kohistani Shina at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) - "Ethnologue report for Shina". Ethnologue.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Shina". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Kohistani Shina". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- "Mosaic Of Jammu and Kashmir".

- Crane, Robert I. (1956). Area Handbook on Jammu and Kashmir State. University of Chicago for the Human Relations Area Files. p. 179.

Shina is the most eastern of these languages and in some of its dialects such as the Brokpa of Dah and Hanu and the dialect of Dras, it impinges upon the area of the Sino-Tibetan language family and has been affected by Tibetan with an overlay of words and idioms.

- Braj B. Kachru, Yamuna Kachru, S. N. Sridhar (2008). Language in South Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 144. ISBN 9781139465502.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Itagi, N. H. (1994). Spatial aspects of language. Central Institute of Indian Languages. p. 73. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

The Shina dialects of India have retained both initial and final OIA consonant clusters. The Shina dialects of Pakistan have lost this distinction.

- Bashir 2003, p. 823. "Of the languages discussed here, Shina (Pakistan) and Khowar have developed a written tradition and a significant body of written material exists."

- Schmidt & 2003/2004, p. 61.

- Schmidt & Kohistani 2008, p. 14.

- Bashir 2016, p. 806.

- Bashir 2003, pp. 823–25. The Devanagari scheme was proposed by Rajapurohit (1975, pp. 150–52; 1983, pp. 46–57; 2012, pp. 68–73). The latter two texts also present Perso-Arabic schemes, which in the 2012 book (pp. 15, 60) is given as primary.

- Rajapurohit 2012, p. 28–31.

- Rajapurohit 2012, p. 32–33.

Bibliography

- Bashir, Elena L. (2003). "Dardic". In George Cardona, Dhanesh Jain (eds.) (eds.). The Indo-Aryan languages. Routledge language family series. Y. London: Routledge. pp. 818–94. ISBN 978-0-7007-1130-7.CS1 maint: uses editors parameter (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bashir, Elena L. (2016). "Perso-Arabic adaptions for South Asian languages". In Hock, Hans Henrich; Bashir, Elena L. (eds.). The languages and linguistics of South Asia: a comprehensive guide. World of Linguistics. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 803–9. ISBN 978-3-11-042715-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rajapurohit, B. B. (1975). "The problems involved in the preparation of language teaching material in a spoken language with special reference to Shina". Teaching of Indian languages: seminar papers. University publication / Department of Linguistics, University of Kerala. V. I. Subramoniam, Nunnagoppula Sivarama Murty (eds.). Trivandrum: Dept. of Linguistics, University of Kerala.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rajapurohit, B. B. (1983). Shina phonetic reader. CIIL Phonetic Reader Series. Mysore: Central Institute of Indian Languages.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rajapurohit, B. B. (2012). Grammar of Shina Language and Vocabulary : (Based on the dialect spoken around Dras) (PDF).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schmidt, Ruth Laila (2003–2004). "The oral history of the Daṛmá lineage of Indus Kohistan" (PDF). European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (25/26): 61–79. ISSN 0943-8254.

- Schmidt, Ruth Laila; Kohistani, Razwal (2008). A grammar of the Shina language of Indus Kohistan. Beiträge zur Kenntnis südasiatischer Sprachen und Literaturen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-05676-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Buddruss, Georg (1983). "Neue Schriftsprachen im Norden Pakistans. Einige Beobachtungen". In Assmann, Aleida; Assmann, Jan; Hardmeier, Christof (eds.). Schrift und Gedächtnis: Beiträge zur Archäologie der literarischen Kommunikation. W. Fink. pp. 231–44. ISBN 978-3-7705-2132-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) A history of the development of writing in Shina

- Degener, Almuth; Zia, Mohammad Amin (2008). Shina-Texte aus Gilgit (Nord-Pakistan): Sprichwörter und Materialien zum Volksglauben, gesammelt von Mohammad Amin Zia. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-05648-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Contains a Shina grammar, German-Shina and Shina-German dictionaries, and over 700 Shina proverbs and short texts.

- Radloff, Carla F. (1992). Backstrom, Peter C.; Radloff, Carla F. (eds.). Languages of northern areas. Sociolinguistic survey of Northern Pakistan. 2. Islamabad, Pakistan: National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rensch, Calvin R.; Decker, Sandra J.; Hallberg, Daniel G. (1992). Languages of Kohistan. Sociolinguistic survey of Northern Pakistan. Islamabad, Pakistan: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i- Azam University.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zia, Mohammad Amin (1986). Ṣinā qāida aur grāimar (in Urdu). Gilgit: Zia Publishers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zia, Mohammad Amin. Shina Lughat (Shina Dictionary).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Contains 15000 words plus material on the phonetics of Shina.

External links

| Shina language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

- Sasken Shina, contains materials in and about the language

- 1992 Sociolinguistic Survey of Shina