Rio Grande Valley

The Rio Grande Valley is a transborder socio-cultural region located in a floodplain draining into the Rio Grande river near its mouth.[1] The region includes the southernmost tip of South Texas and a portion of northern Tamaulipas, Mexico. It consists of the Brownsville, Harlingen, Weslaco, Pharr, McAllen, Edinburg, Mission, San Juan, and Rio Grande City metropolitan areas in the United States and the Matamoros, Río Bravo, and Reynosa metropolitan areas in Mexico.[2][3] These cities are surrounded by many small neighborhoods or colonias.[4] The area is generally bilingual in English and Spanish with a fair amount of Spanglish[5] due to the diverse history of the region.[6] There is a large seasonal influx of winter Texans or Texans who come down from the north for the winter and then go back up north before summer hits.[7]

| Rio Grande Valley | |

|---|---|

Map of the Rio Grande Valley | |

| Floor elevation | 285 ft (87 m) |

| Area | 4,872 sq mi (12,620 km2) |

| Geography | |

| Location | United States, Texas |

| Coordinates | 26.22°N 98.12°W |

History

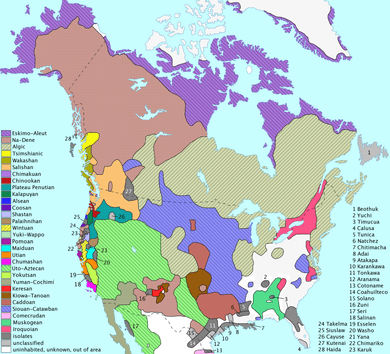

Pre-Spanish Colonization

Native peoples lived in small tribes in the area before the Spanish conquisition.[8] The native tribes in South Texas were known to be hunter-gatherer peoples.[9] The area was known for its smaller nomadic tribes collectively called Coahuiltecan.[9] Native archeological excavations near Brownsville have shown evidence of prehistoric shell trading.[10]

Spanish Colonization

Initially the Spanish had a hard time conquering the area due to the differences in native languages so they mainly focused on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico also known as the Seno Mexicano.[11] There was also a major conflict on who would be the one to conquer the region. Antonio Ladrón de Guevara wanted to colonize the region but the Viceroy of New Spain José Tienda de Cuervo doubted Ladrón de Guevara's character eventually leading to a royal Spanish declaration preventing Ladrón de Guevara from participating in colonization efforts.[12][13]

The first Villas in the region were settled in Laredo and Reynosa in 1767.[11] In 1805 the Spanish government solidified the autonomy of the region by defining the territory of Nuevo Santander as south of the colony of Tejas from the Nueces River south to Tampico, Charcas, and Valles.[11][13] The local government of the region had a rough start with various indigenous wars up until 1812.[14] In 1821 after the Mexican War of Independence the state was renamed Tamaulipas.

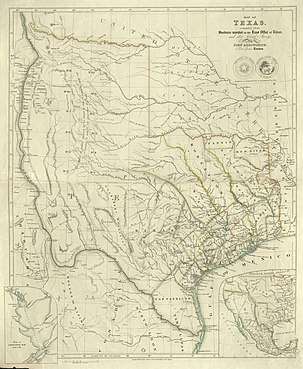

The Republic of Texas

The Texas Revolution of 1835-1836 put the majority of what is now called the Rio Grande Valley under contested Texan sovereignty.[6] The area also became a thoroughfare for runaway slaves fleeing to Mexico.[15]

1846-1900s Becoming Part of the United States of America

In 1844 James K. Polk annexed the Republic of Texas into the United States against British and Mexican sentiments.[16] According to several scholars the Mexican–American War broke out because of the annexation.[16] The area along the Rio Grande was the source of several major battles including the Battle of Resaca de la Palma near Brownsville.[17] The war ended in 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo which defined the United States' southern border as the Rio Grande River. The change in government led to a mass migration from Tamaulipas to the United States side of the river.[18]

From the end of the Mexican-American War the population of the valley began to grow and farmers began to raise cattle in the area.[18] Despite the end of the formal war in 1848, there continued to be inter-racial strife between native peoples and the white settlers over land through the 1920s.[8][19]

Early 1900s and the Mexican Revolution

_(14586900509).jpg)

At the turn of the 20th century trade and immigration between Mexico and the United States was a normal part of society.[2] The development of the St. Louis, Brownsville, and Mexico Railway in 1903 and the irrigation of the Rio Grande allowed the Rio Grande Valley to develop into profitable farmland.[20] Droughts in the 1890s and early 1900s caused smaller farmers and cattle ranchers to lose their lands. Rich white settlers brought by the railroad bought the land and displaced the Tejano ranchers.[21]

Meanwhile, across the river Mexico was dealing with the Mexican Revolution.[20] The revolution spilled over the border through cross-border supply raids, and in response President Taft sent the United States Army into the region beginning in 1911 and continuing until 1916 when the majority of the United States armed forces were stationed in the region. Texas governor Oscar Colquitt also sent the Texas Rangers into the area to keep the peace between Mexicans and Americans.[2]

The region played host to several well known conflicts including the backlash from the Plan of San Diego, and the racially fueled violence of Texas Ranger Harry Ransom.[2] In 1921 the United States Border Patrol came to the region with less than 10 officers.[22]

Initially the agency was focused on import/export business, especially alcohol during Prohibition in the United States, but later moved to detaining illegal aliens.[23]

The region had a significant increase of Border Patrol agents during World War I in conjunction with the Zimmermann Telegram.[24] The Texas Rangers also increased their presence as law enforcement in the region with a new class of Ranger that focused on determining Tejano loyalty.[25] They were often violent, carrying out retaliatory murders.[24] They were never held accountable to the law even though charges were brought in the Texas senate.[26]

There were two major military training facilities in the valley in Brownsville and Harlingen during World War II.[27]

Post World War II to Present

.jpg)

The North American Free Trade Agreement, also known as NAFTA, was established in 1994 as a trade agreement between the three North American countries, The United States, Mexico, and Canada. NAFTA was supposed to increase trade with Mexico as they lowered or eliminated tariffs on Mexican goods.[28] Exports and imports tripled in the region and accounted for a trade surplus of $75 billion.[28] The Rio Grande Valley benefited from NAFTA in retail, manufacturing,and transportation. Due to the influx of jobs and exportation, many people migrated to the RGV, both documented and undocumented.[29] According to Akinloye Akindayomi in Drug violence in Mexico and its impact on the fiscal realities of border cities in Texas: evidence from Rio Grande Valley counties, NAFTA also indirectly aids the rise in immigration and drug smuggling practices between cartels in the region, with cartels profiting with over $80 billion.[29] The Trump Administration decided to make new accords with Mexico and Canada and replaced NAFTA with the new trade agreement, United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) in 2018.[30]

After the September 11 attacks, the Customs Border Security Act of 2001 established United States Border Patrol interior checkpoints with some situated at the north end of the Rio Grande Valley. This allows for a second line of defense in the ever increasing subtlety of smuggling.

More recently the organization We Build The Wall has begun construction on a section of the border wall in the valley. Local residents have express concerns about the project including the site's proximity to the National Butterfly Center and the Rio Grande River with its potential for seasonal flooding.[31] The U.S. Section of the International Boundary and Water Commission has ordered We Build The Wall to stop until they can review whether or not the construction violates a Treaty to resolve pending boundary differences and maintain the Rio Grande and Colorado River as the international boundary between the United States and Mexico signed in 1970.[32]

Geography and demographics

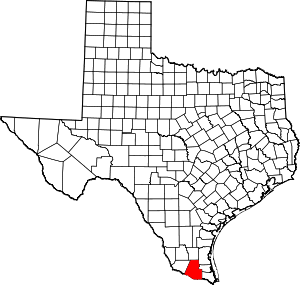

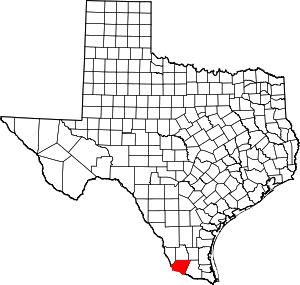

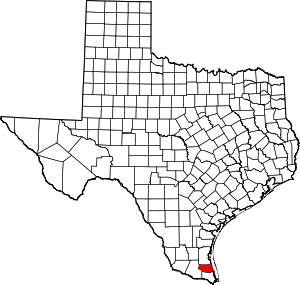

The Rio Grande Valley is not a true valley, but a floodplain, containing many oxbow lakes or resacas formed from pinched-off meanders in earlier courses of the Rio Grande.[1] Early 20th-century land developers, attempting to capitalize on unclaimed land, utilized the name "Magic Valley" to attract settlers and appeal to investors. The Rio Grande Valley is also called El Valle, the Spanish translation of "the valley", by those who live there.[33] The residents of the Rio Grande Valley no longer refer to the area as "El Mágico Valle del Río Grande" ("The Magical Valley of the Rio Grande"), but as "the valley". The main region is within four Texan counties: Starr County, Hidalgo County, Willacy County, and Cameron County. As of January 1, 2012, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated the population of the Rio Grande Valley at 1,305,782.[34] According to the U.S. Census Bureau in 2008, 86 percent of Cameron County, 90 percent of Hidalgo County, 97 percent of Starr County, and 86 percent of Willacy County are Hispanic.[35]

Major Metropolitan Areas

The largest city is Brownsville (Cameron County), followed by McAllen (Hidalgo County). Other major cities include Harlingen, Edinburg, Mission, Rio Grande City, Raymondville, Weslaco, Hidalgo and Pharr.[36] On the Mexican side of the border Matamoros, Río Bravo, and Reynosa are major cities.[2][3]

Colonias

The major metropolitan areas in the Rio Grande River Valley are surrounded by smaller rural communities called Colonias.[37] These communities are primarily poor and Hispanic. A case study of Corazón, a colonia in the region was studied and found to contain a majority of Hispanic working-class people who spoke Spanish as their primary language.[38] The areas often lack basic services like sanitation and sewage.[39] Flooding and lack of trash collection are among the major sanitation issues in colonias.[37] According to several sources including the book Justice and Space Matter in a Strong, United Latino Community, zoning laws and building codes are not enforced.[38] Many of these colonias are mixes of mobile homes and self-constructed houses owned by the residents.[40] The Bracero program enacted in the 1940s allowed Mexicans to cross the border and work in the agricultural fields. Most worked in the Rio Grande Valley, and due to a shortage of affordable houses, developers started selling them land in unincorporated areas; these clusters of homes over time became what are now known as Colonias.[37] According to the Housing Assistance Council, a nonprofit organization that tracks rural housing, approximately 1.6 million people live in 1,500 recognized colonias alongside the Mexico–United States border.[37]

Language Use

The residents of the Lower Rio Grande Valley are generally bilingual in English and Spanish often mixing into Spanglish depending on demographics and context.[38][41] Government statistics for the region are often underreported due to underlying immigration issues.[42]

Spanish

Spanish language plays an important role in all aspects of life. In 1982 a statistically significant majority of people in the Rio Grande Valley spoke Spanish.[43] People speak Spanish to communicate in all aspects of life including business, government, and at home.[41]

| Cameron

County |

Hidalgo

County |

Starr

County |

Willacy

County | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population 5 years and older | 384,007 | 759,143 | 56,972 | 20,442 |

| Speaks English only | 102,074 | 119,489 | 2,072 | 8,252 |

| Language other than English | 281,933 | 639,654 | 54,900 | 12,190 |

| Spanish | 278,451 | 631,638 | 54,838 | 12,005 |

| Other Indo-European Languages | 1,302 | 2,126 | 3 | 155 |

| Asian and Pacific Islander Languages | 1,511 | 5,460 | 53 | 22 |

| Other Languages | 669 | 430 | 6 | 8 |

People often prefer Spanish to English in when interfacing with government officials as seen in the response to the region's 2018 flooding.[45]

Residents of the area often switch from English to Spanish and inter-mix both languages, this is called Spanglish. Spanglish is more than switching or knowing both languages, but it is a form of identifying with a community and living the environment.[5]

Religion

According to the 2010 U.S. Religion Census: Religious Congregations and Membership Study the Rio Grande Valley is majority Unclaimed religious preference with Catholicism, Protestantism and other faith traditions playing statistically significant roles.[46] This trend has stayed the same with the organization's 2000, 1990, and 1980 censuses.[46]

Catholicism

The Catholic church has been present in the Rio Grande Valley since the Spanish colonization of the region.[47]

Basilica of the National Shrine of Our Lady of San Juan del Valle

In San Juan, Texas the Basilica of the National Shrine of Our Lady of San Juan del Valle is a major Catholic shrine. Legend has it that after an accident with an acrobatic troupe an Native woman placed a statue of the virgin on a dead child and the child miraculously came back to life.[48] In 1920 the statue was enshrined in a chapel.[49] In 1970 a plane crashed into the Basilica causing serious damage but the statue of Our Lady of San Juan was unharmed.[50]

Protestantism (Christian)

As of 2010 there were several organized Protestant churches in the Lower Rio Grande Valley.[46] In the 1850s Ramon Motsalvage and his wife were Presbyterian missionaries to Brownsville, Texas.[51] They were publicly opposed by the local Catholic Curate but well received by the local press.[52]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

As of the 2010 U.S. Religion Census: Religious Congregations and Membership Study, there are 26 congregations with about 17,000 members.[46] The church began with a small Branch serving the area in the early 1900s and by 1952 there were two Stakes.[53] Also in 1952, the El Paso 3rd Ward; the first Spanish speaking Ward in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was created.[54]

In January 1996 Gordon B. Hinckley then the church's president with Jeffrey R. Holland of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles (LDS Church) visited the congregations of the region.[55]

Most recently the church is preparing to construct the McAllen Texas Temple.[56] A Temple is different from a regular meetinghouse and is a sacred space where members go to make promises with God.[57]

Other religious groups

Muslims

The Al Khair Islamic Society of Rio Grande Valley in Edinburg, Texas provides education and worship services for Muslims in the valley.[58] It's Arridwan Mosque holds a yearly Islamic Festival.[59]

Climate

The Rio Grande Valley experiences a warm and fair climate that brings visitors from many surrounding areas.[7] Temperature extremes range from triple digits during the summer months to freezing during the winter.[62] While the valley has seen severe cold events before, such as the 2004 Christmas snow storm, the region only occasionally experiences temperatures at or below freezing.[62]

The Rio Grande Valley's proximity to the Gulf of Mexico makes it a target for hurricanes. Though not impacted as frequently as other areas of the Gulf Coast of the United States, the valley has experienced major hurricanes in the past. Hurricanes that have made landfall in or near the area include: Hurricane Beulah (1967), Hurricane Allen (1980), Hurricane Gilbert, Hurricane Bret, Hurricane Dolly (2008), Hurricane Alex (2010), and Hurricane Harvey. Having an especially flat terrain, the valley usually experiences the catastrophic effects of tropical cyclones in the form of flooding.[45]

Tourism

The Lower Rio Grande Valley encompasses landmarks that attract tourists, and popular destinations include: Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge, Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge, and Bentsen-Rio Grande Valley State Park; and on the coast: South Padre Island, Brazos Island, and the Port Isabel Lighthouse.

The valley is a popular waypoint for tourists visiting northeast Mexico.[63] Popular destinations across the border and Rio Grande include: Matamoros, Nuevo Progreso, Río Bravo, and Reynosa, all located in the Mexican state of Tamaulipas.

The valley also attracts tourists from the Mexican states of Tamaulipas, Nuevo León, Coahuila, and Mexico, D.F. (México City).

Places of historical interest

- Basilica of the National Shrine of Our Lady of San Juan del Valle

- First Lift Station

- Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge

- Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge

- Hugh Ramsey Nature Park

- Los Ebanos Ferry, last hand-operated ferry on the Rio Grande

- La Lomita Historic District

- Fort Brown

- Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Site

- Resaca de la Palma

- Rancho de Carricitos[64]

- USMC War Memorial original plaster working model, located on the campus of the Marine Military Academy in Harlingen

- Museum of South Texas History, originally the County Court House and Jail, built in the late 19th century

- Battle of Palmito Ranch, location of the last battle of the Civil War

- Brownsville Raid

- Battle of Resaca de la Palma

Economy

The valley is historically reliant on agribusiness and tourism. Cotton, grapefruit, sorghum, maize, and sugarcane are its leading crops, and the region is the center of citrus production and the most important area of vegetable production in the State of Texas. Over the last several decades, the emergence of maquiladoras (factories or fabrication plants) has caused a surge of industrial development along the border, while international bridges have allowed Mexican nationals to shop, sell, and do business in the border cities along the Rio Grande. The geographic inclusion of South Padre Island also drives tourism, particularly during the Spring Break season, as its subtropical climate keeps temperatures warm year-round.[65] During the winter months, many retirees (commonly referred to as "Winter Texans") arrive to enjoy the warm weather,[7] access to pharmaceuticals and healthcare in Mexican border crossings such as Nuevo Progreso.[66] There is a substantial health-care industry with major hospitals and many clinics and private practices in Brownsville, Harlingen, and McAllen.

Texas is the third largest producer of citrus fruit in United States, the majority of which is grown in the Rio Grande Valley. Grapefruit make up over 70% of the valley citrus crop, which also includes orange, tangerine, tangelo and Meyer lemon production each Winter.[67]

There are two minor professional sports teams that play in the Rio Grande Valley: The Rio Grande Valley Vipers (basketball), and Rio Grande Valley FC Toros (soccer). Defunct teams that previously played in the region include: the Edinburg Roadrunners (baseball), La Fiera FC (indoor soccer), Rio Grande Valley Ocelots FC,(soccer), Rio Grande Valley WhiteWings (baseball), Rio Grande Valley Killer Bees (ice hockey), and the Rio Grande Valley Sol (indoor football).

One of the valley's major tourist attractions is the semi-tropical wildlife. Birds and butterflies attract a large number of visitors every year all throughout the entire valley. Ecotourism is a major economic force in the Rio Grande Valley.[68][69]

Politics

| Year | GOP | DEM | Others |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 29.0% 81,885 | 67.6% 190,922 | 3.40% 9,544 |

| 2012 | 29.6% 68,927 | 69.3% 161,804 | 1.00% 4,433 |

| 2008 | 31.2% 69,287 | 67.8% 150,424 | 1.00% 2,033 |

| 2004 | 45.8% 90,493 | 53.8% 106,300 | 0.40% 789 |

| 2000 | 39.5% 69,801 | 59.1% 104,327 | 1.40% 2,505 |

| 1996 | 29.2% 44,959 | 65.8% 101,327 | 5.00% 7,605 |

| 1992 | 30.7% 49,798 | 56.6% 91,667 | 12.7% 20,523 |

| 1988 | 37.0% 56,479 | 62.5% 95,425 | 0.50% 671 |

| 1984 | 46.5% 68,602 | 53.2% 78,625 | 0.30% 435 |

| 1980 | 42.9% 51,233 | 54.9% 65,571 | 2.14% 2,559 |

| 1976 | 35.3% 37,853 | 64.0% 68,661 | 0.70% 772 |

| 1972 | 56.8% 48,442 | 42.7% 36,410 | 0.05% 390 |

| 1968 | 38.1% 28,831 | 55.1% 41,665 | 6.80% 5,147 |

| 1964 | 34.1% 23,002 | 65.7% 44,374 | 0.20% 169 |

| 1960 | 40.4% 25,465 | 59.0% 37,239 | 0.60% 360 |

| 1956 | 54.2% 27,425 | 44.7% 22,621 | 1.04% 525 |

| 1952 | 60.2% 32,185 | 39.6% 21,189 | 0.15% 79 |

| 1948 | 36.8% 11,764 | 60.8% 19,439 | 2.5% 786 |

| 1944 | 37.5% 10,211 | 56.6% 15,406 | 5.86% 1,595 |

| 1940 | 36.4% 9,065 | 63.4% 15,789 | 0.25% 63 |

| 1936 | 26.1% 5,818 | 71.7% 15,960 | 2.24% 498 |

| 1932 | 20.9% 5,045 | 78.0% 18,837 | 1.14% 275 |

| 1928 | 49.7% 8,368 | 50.1% 8,897 | 0.16% 27 |

| 1924 | 24.6% 2,395 | 71.3% 6,950 | 4.17% 407 |

| 1920 | 38.0% 2,115 | 60.9% 3,382 | 1.06% 59 |

| 1916 | 19.5% 805 | 78.8% 3,250 | 1.67% 69 |

| 1912 | 9.17% 445 | 85.0% 4,125 | 5.83% 283 |

According to the Secretary of State of Texas, the region has a better voter turnout in presidential elections.[70] The region is represented by Ted Cruz and John Cornyn in the United States Senate and in the United States House of Representatives by Filemon Vela Jr. and Vicente Gonzalez.[71]

Politiqueras, women hired to help elderly people vote, are crucial in South Texas elections. There was an incident in 2013 where Politiqueras were arrested accused of bribing voters.[72] Cecilia Ballí of Texas Monthly wrote that voters expect to get favors from politicians they vote for, and if they do not get these favors they become resentful of politicians as a whole.[73]

In the twenty-first century, the dominance of agribusiness has caused political issues, as jurisdictional disputes regarding water rights have caused tension between farmers on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border. Scholars, including Mexican political scientist Armand Peschard-Sverdrup, have argued that this tension has created the need for a re-developed strategic transnational water management.[74] Some have declared the disputes tantamount to a "war" over diminishing natural resources.[75] Climatologists believe water scarcity in the Valley will only increase as climate change alters the precipitation patterns of the region.[76]

The 2018 US Senate Democratic candidate Beto O'Rourke received 164,232 votes from the region in his failed bid to oust incumbent Republican US Senator from Texas Ted Cruz.[77]

In 2019 the mayor of Edinburg, Texas, Richard Molina, was arrested for voter fraud.[72]

Education

Historically education has posed significant challenges to schools in the region. Schools in the early 1920s through the 1940s were racially segregated in the Rio Grande Valley. In 1940 a study showed the need for improvement in cultural differentiation of instruction.[78] The Texas Supreme court in Del Rio ISD v. Salvatierra reinforced the racial segregation.[79] In 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Bilingual Education Act, helping students whose second language was English. The Act gave financial assistance to local schools to create bilingual programs, enabling Mexican students to integrate white schools.[79] The area like many others had a hard time integrating.[80] Texas still has the bilingual program, while states like: California, Arizona, and Massachusetts, have removed the bill and passed similar propositions stating that students would only be taught in English.[79] The bilingual program in the Rio Grande Valley is still in effect especially with Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals students in the area.[79]

Colleges and universities located in the Rio Grande Valley include:

- Texas A&M Health Science Center, School of Public Health - McAllen

- Texas A&M University - McAllen Campus

- University of Texas Rio Grande Valley — Entered into full operation in 2015 with the merger of the University of Texas at Brownsville and the University of Texas–Pan American. UTRGV will include a new medical school.

- Texas Southmost College

- Texas State Technical College

- South Texas College

- University of Texas Health Science Center - Regional Academic Health Center[81]

Sports

| Club | Sport | League | Venue | Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rio Grande Valley FC Toros | Soccer | USLC | H-E-B Park | 9,735 |

| Rio Grande Valley Vipers | Basketball | NBA G League | Bert Ogden Arena | 9,000 |

| RGV Barracudas FC | Indoor Soccer | MASL | Payne Arena | 6,800 |

| UTRGV Basketball Men | NCAA Division I Basketball | WAC | UTRGV Fieldhouse | 2,500 |

Defunct

| Club | Sport | League |

|---|---|---|

| Rio Grande Valley Dorados | Arena football | af2 (2004–09) |

| Rio Grande Valley Bravos FC | Soccer | PDL (2008–010) |

| Rio Grande Valley Magic | Arena football | SIFL (2011) LSFL (2012) |

| Rio Grande Valley Sol | Arena football | LSFL (2014) XLIF (2015) |

| Hidalgo La Fiera | Arena soccer | MASL (2012–14) |

| Edinburg Roadrunners | Baseball | Texas–Louisiana League (2001) Central Baseball League (2002–05) United League Baseball (2006–10) North American League (2011–12) |

| Rio Grande Valley Giants | Baseball | Texas League (1960–61) |

| Rio Grande Valley WhiteWings | Baseball | Texas–Louisiana League (1994–2001) Central Baseball League (2002–03) United League Baseball (2006–10) North American League (2011–12) |

| Texas Thunder | Baseball | United League Baseball (2009–10) North American League (2011–12) United League Baseball (2013) |

| Rio Grande Valley Killer Bees | Ice hockey | CHL (2003–12) |

| Rio Grande Valley Killer Bees | Ice hockey | NAHL (2013–15) |

| Rio Grande Valley Killer Bees | Ice hockey | USA Central Hockey League (2018) |

Hospitals

- Cornerstone Regional Hospital, Edinburg, Texas

- Edinburg Children's Hospital, Edinburg, Texas

- Edinburg Regional Medical Center, Edinburg, Texas

- Doctors Hospital at Renaissance, Edinburg, Texas

- Harlingen Medical Center, Harlingen, Texas

- McAllen Heart Hospital, McAllen, Texas

- McAllen Medical Center, McAllen, Texas

- Rio Grande Regional Hospital, McAllen, Texas

- Rio Grande State Hospital, Harlingen, Texas

- Solara Hospital, Harlingen, Texas

- VA Health Care Center at Harlingen. Harlingen, Texas

- Valley Baptist Medical Center, Harlingen, Texas

- Valley Baptist Medical Center, Brownsville, Texas

- Valley Regional Medical Center, Brownsville, Texas

- Knapp Medical Center, Weslaco, Texas

- Mission Regional Medical Center, Mission, Texas

Media

Magazines

- The Go Guide (published by Above Group Advertising Agency)

- Rio Grande Magazine

- Viva el Valle

- RGV Drives Magazine (published by MAT Media Solutions)

- RGVision Magazine (published by RGVision Media)

Newspapers

- Valley Town Crier - owned by Gatehouse Media

- The Edinburg Review - owned by Gatehouse Media

- Valley Bargain Book - owned by Gatehouse Media

- El Periódico USA

- El Nuevo Heraldo - owned by AIM Media Texas

- Mega Doctor News

- Texas Border Business

- The Brownsville Herald - owned by AIM Media Texas

- The Island Breeze - owned by AIM Media Texas

- The Monitor - owned by AIM Media Texas

- Valley Morning Star - owned by AIM Media Texas

- Valleywood Magazine

Television

- KGBT-TV/DT channel 4, Independent Station

- KRGV-TV/DT Channel 5 News, ABC Affiliate

- KVEO-TV/DT News Center 23/CBS 4 (DT-2), NBC/CBS Affiliate

- KCWT-CD 21, The CW Affiliate

- KTFV-CD 32, Telefutura Affiliate

- KMBH TV/DT 38, PBS Affiliate

- KLUJ-TV/DT 44, TBN Affiliate

- KTLM-TV/DT 40, Telemundo Affiliate

- KNVO TV/DT 48, Univision Affiliate

- KFXV-LD 67, Fox 2 News, Fox Affiliate

- XERV-TDT 9.1 Las Estrellas, Televisa

- XHAB-TDT 7.1 Vallevision, Televisa

- XHOR-TDT 14.1 Azteca 7, TV Azteca

- XHREY-TDT1.1 Azteca Uno, TV Azteca

Radio

- BLST Blistering Listens and Strange Sounds, Thank You (Rock, Punk, Hip-Hop, Electronic, Experimental, Ambient, & more)

- KBFM Wild 104 (Hip Hop/Top 40 - IHeart Media)

- XEEW-FM Los 40 Principales 97.7 (Top 40 Spanish/English)

- KBTQ 96.1 Exitos (Spanish Oldies)Univision

- KCAS 91.5 FM (Christian, Teaching/Preaching/Music)

- KESO Digital 92.7 (Internacional, Spanish Top 40)

- KFRQ Q94.5 The Rock Station (Classic/Modern/Hard Rock)

- KGBT 1530 La Tremenda (Univision)

- KGBT-FM 98.5 FM (Regional Mexican) Univision

- KHKZ Kiss FM 105.5 & 106.3 (Hot Adult Contemporary)

- KIRT 1580 AM Radio Imagen (Variety, Spanish contemporary)

- KIWW (Spanish)

- KJAV 104.9 Jack FM

- KKPS La Nueva 99.5 (Regional Mexican)

- KJJF/KHID 88.9/88.1 NPR (Classical/Public Radio)

- KNVO-FM Super Estrella (Super Star) 101.1

- KQXX Kiss FM 105.5 & 106.3 (Hot Adult Contemporary, simulcast of KHKZ - IHeart Media)

- KTEX 100.3 (Mainstream Country - IHeart Media)

- KURV 710 AM Heritage Talk Radio (part of the BMP family of stations)

- KVLY 107.9 Mix FM (Top 40)

- KVMV 96.9 FM (Christian, Contemporary Music) World Radio Network

- KVNS 1700AM (Fox Sports Radio - IHeart Media)

- XHRYA-FM 90.9 Mas Music (Spanish/English Mix)

- KBUC Super Tejano102.1 (Tejano)

Notable people

A list of notable people who were born, lived, or died in the Rio Grande Valley includes:

- David V. Aguilar (Chief Border Patrol Agent, United States Border Patrol)

- Cristela Alonzo (comedian, actress, writer, producer)

- Micaela Alvarez (federal judge)

- Natalia Anciso (contemporary artist)

- Gloria E. Anzaldúa (writer, poet, philosopher)

- Cathy Baker (television performer)

- Lloyd Bentsen (U.S. Secretary of the Treasury; U.S. Senator; 1988 Vice-Presidential candidate)

- James Carlos Blake (novelist)

- Harlon Block (Iwo Jima flag raiser)

- David Bowles (poet, author and translator)

- William S. Burroughs (writer; his time as a farmer in the valley in Pharr, Texas, is briefly chronicled in his books Junky and Queer)

- Pedro Cano (Medal of Honor recipient)

- Rolando Cantú (football player)

- Raúl Castillo (actor)

- Thomas Haden Church (actor)

- Freddy Fender (actor, musician, lyricist)

- Mike Fossum (astronaut)

- Reynaldo Guerra Garza (United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit judge)

- Kika de la Garza (U.S. Representative)

- Roberto Garza (football player)

- Xavier Garza (author and illustrator)

- Tony Garza (U.S. Ambassador to Mexico)

- Alfredo C. Gonzalez (Medal of Honor Recipient, U.S. Marine Veteran)

- Matt Gonzalez (2008 Vice-Presidential candidate; former president of the Board of Supervisors of San Francisco, California)

- Esteban Jordan (accordionist)

- Bill Haley (musician)

- Catherine Hardwicke (writer; film director-producer)

- Rolando Hinojosa (author)

- Rubén Hinojosa (U.S. Representative)

- Kris Kristofferson (musician, actor, songwriter)

- Tom Landry (American football coach, Mission, Texas)

- Bobby Lackey (College Football Player; Weslaco, Texas)

- José M. López (Medal of Honor Recipient)

- Domingo Martinez (author)

- Eduardo Martinez (Historian, Journalist)

- Roy Mitchell-Cárdenas (musician)

- Jack Morava (mathematician)

- Rachel McLish (Ms. Olympia; actress)

- Bobby Morrow (Olympic gold medalist)

- Billy Gene Pemelton (1964 Olympian)

- Eduardo "Eddie" Perez (Tejano Roots Hall of Fame inductee 2005, Tejano Academy Of Musicians Legacy Award 2008, Latin Grammy winner 2013, Edinburg, Texas)

- Major Samuel Ringgold (father of modern artillery)

- Charles M. Robinson III (author)

- Valente Rodriguez (actor)

- Ricardo Sanchez (U.S. Army lieutenant general; Ground forces commander in Iraq)

- Julian Schnabel (filmmaker)

- Adela Sloss Vento

- Merced Solis aka Tito Santana (wrestler)

- Nick Stahl (actor)

- Emeraude Toubia (actress)

- Filemon Bartolome Vela (federal judge)

- Eric Miles Williamson (novelist, literary critic, professor)

- Maximillian "Max" Alexander Decker (actor)

See also

- Flora of the U.S. Rio Grande Valleys

References

- Odintz, Mark and Vigness (2010-06-15). "Rio Grande Valley". tshaonline.org. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- Weber, John, 1978-. From South Texas to the nation : the exploitation of Mexican labor in the twentieth century. Chapel Hill. ISBN 9781469625256. OCLC 921988476.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "From the Archives of South Texas". Journal of South Texas. 33 (1): 150–152. 2019 – via EBSCO Host.

- Hidalgo, Margarita (1995). "Language and ethnicity in the "taboo" region: the U.S.-Mexico border". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 0165-2516,01652516. Germany, Republic of, Germany, Republic of: Walter de Gruyter GmbH (114): 29–45. doi:10.1515/ijsl.

- "Viva Spanglish!". Texas Monthly. 2001-10-01. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- Roell, Craig H. (2013). Matamoros and the Texas Revolution. Denton: Texas State Historical Association. ISBN 978-0876112663. OCLC 857404621.

- "What is a Winter Texan, Winter Texans lifestyle". wintertexaninfo.com. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- Leiker, James N., 1962- (2002). Racial borders : Black soldiers along the Rio Grande (1st ed.). College Station: Texas A & M University Press. ISBN 1585449636. OCLC 50667869.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Boswell, Angela, 1965- (2018-10-12). Women in Texas history (First ed.). College Station. ISBN 9781623497088. OCLC 1056952235.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Arnn, John W. (2012). Land of the Tejas : native American identity and interaction in Texas, a.d. 1300 to 1700. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292734999. OCLC 774399262.

- Alonzo, Armando C. (January 1998). Tejano legacy : rancheros and settlers in south Texas, 1734-1900 (First ed.). Albuquerque. ISBN 9780826328502. OCLC 865821392.

- Osante, Patricia (Jul–Dec 2013). "A project of Antonio Ladrón de Guevara for the settlements of Nuevo Santander, 1767". Estudios de historia novohispana. 49: 170–191. ISSN 0185-2523 – via SciELO.

- de Lejarza, Fidel (1947). Conquista espiritual del Nuevo Santander (in Spanish). Madrid, Spain: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Instituto Santo Toribio de Mogrovejo, Madrid.

- Medina Bustos, José Marcos; Trejo Contreras, Zulema (September 1, 2014). "Catherine Andrews y Jesús Hernández Jaimes (2012), Del Nuevo Santander a Tamaulipas. Génesis y construcción de un estado periférico mexicano 1770-1825". Revista Región y Sociedad. El Colegio de Sonora. 26 (61): 357+ – via Gale Academic Onefile.

- Torget, Andrew J. Seeds of Empire : Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800-1850 The David J. Weber Series in the New Borderlands History. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

- McGill, Sara Ann. The war for Texan independence & the annexation of Texas. [Place of publication not identified]. ISBN 1429804351. OCLC 994400707.

- Bauer, K. Jack (Karl Jack), 1926- (©1993, ©1974). The Mexican War, 1846-1848 (Bison books ed.). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803261071. OCLC 25746154. Check date values in:

|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Alonzo, Armando C. (January 1998). Tejano legacy : rancheros and settlers in south Texas, 1734-1900 (First ed.). Albuquerque. ISBN 9780826328502. OCLC 865821392.

- Brown, James Henry (1893). History of Texas, from 1865 to 1892. (In Two Volumes). 2. St. Louis: L. E. Daniell: Becktold & Co.

- "FROM THE ARCHIVES OF SOUTH TEXAS". Journal of South Texas. 33 (1): 150–152. 2019 – via EBSCO Host.

- Sadasivam, Naveena (August 21, 2018). "The Making of the 'Magic Valley'". The Texas Observer. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

- "Rio Grande Valley Sector Texas | U.S. Customs and Border Protection". www.cbp.gov. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

- "Border Patrol History | U.S. Customs and Border Protection". www.cbp.gov. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

- Klein, Christopher. "Everything You Need to Know About the Mexico-United States Border". HISTORY. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

- Martinez, Monica Muñoz (2014). "Recuperating Histories of Violence in the Americas: Vernacular History-Making on the US–Mexico Border". American Quarterly. 66 (3): 661–689. doi:10.1353/aq.2014.0040. ISSN 1080-6490.

- Force, Texas Legislature Joint Committee of the House and Senate in the Investigation of the Texas State Ranger. "Texas Legislature, Joint Committee of the House and Senate in the Investigation of the Texas State Ranger Force: An Inventory of the Joint Committee of the House and Senate in the Investigation of the Texas State Ranger Force Transcript of Proceedings at the Texas State Archives, 1919". legacy.lib.utexas.edu. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

- "Rio Grande Valley's Role in World War II". KVEO-TV. 2018-06-28. Retrieved 2019-11-20.

- Cavazos, Nora Lisa (August 2014). "BORDERLANDS OF THE RIO GRANDE VALLEY: WHERE TWO WORLDS BECOME ONE" (PDF). Texas State University.

- Akindayomi, Akinloye (July 2014). "Drug violence in Mexico and its impact on the fiscal realities of border cities in Texas: evidence from Rio Grande Valley counties" (PDF). Public and Municipal Finance. 3: 1–11.

- Long, Heather (October 1, 2018). "U.S., Canada and Mexico just reached a sweeping new NAFTA deal. Here's what's in it". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2018-10-01.

- Merchant, Nomaan (November 15, 2019). "Border wall fundraiser claims new construction in Texas". ABC News. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

- Sanchez, Sandra (November 19, 2019). "'We Build the Wall' issued cease and desist to stop construction in South Texas, officials confirm". CBS17.com. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

- Winter Texan Resources for South Padre Island, Brownsville, Harlingen, and the Rio Grande Valley

- 2012 Census Estimates

- Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley Fact Sheet

- Population Estimates for Rio Grande Valley Cities 2000-2004

- Rivera, Danielle Z (Fall 2014). "The Forgotten Americans: A Visual Exploration of Lower Rio Grande Valley Colonias". Michigan Journal of Sustainability. 2 (20181221). doi:10.3998/mjs.12333712.0002.010.

- Bussert-Webb, Kathy; Diaz, María Eugenia; Yanez, Krystal A (2017). Justice & Space Matter in a Strong, Unified Latino Community. New York, New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-1-4331-3205-6.

- "The colonias of the Mexican border: Paving the way". The Economist. 398 (8718). Economist Intelligence Unit N.A. Incorporated. January 27, 2011. p. 30 (US). Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- Galvin, Gaby (May 16, 2018). "On the Border, Out of the Shadows". US News & World Report. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- Mejias, Hugo A.; Anderson, Pamela L. (1984). "Attitudes toward Spanish language maintenance or shift (LMLS) in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of South Texas". Southwest Journal of Linguistics. 7 (2): 116–124. ISSN 0737-4143 – via Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts (LLBA).

- "EDITORIAL: It counts: Census jobs could be chance to relay residents' concerns". Brownsville Herald. October 8, 2019. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- "SELECTED SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS IN THE UNITED STATES". data.census.gov. 2018. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- "SELECTED SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS IN THE UNITED STATES". data.census.gov. 2018. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- Garcia, Cristina M (July 20, 2018). "Congressmen want more Spanish-speaking FEMA workers in RGV". The Monitor. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- Grammich, C., Hadaway, K., Houseal, R., Jones, D. E., Krindatch, A., Stanley, R., & Taylor, R. H. (2018, December 11). U.S. Religion Census Religious Congregations and Membership Study, 2010 (County File).

- Alonzo, Armando (1998). Tejano Legacy: Rancheros and Settlers in South Texas, 1734-1900. United States of America: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-2850-2.

- "OUR LADY OF SAN JUAN DEL VALLE BASILICA NATIONAL SHRINE". Our Sunday Visitor. 105 (2). 2016. p. 12. ISSN 0030-6967.

- "Our History". olsjbasilica.org. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- Gutierrez, Cecilia (April 16, 2019). "Notre Dame Fire Brings Memories of 1970 Valley Church Fire". KRGV.com. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- Chamberlain, H (August 20, 1850). "Our Mission in the Valley of the Rio Grande". American & Foreign Christian Union. 1 (10): 466 – via EBSCOhost.

- KING, A (May 1, 1852). "The Opposition of Rome Everywhere the Same". American & Foreign Christian Union: 134–136.

- Bradshaw, Silas William; Bradshaw, Mabel Moody Hankins (February 15, 1999). "Milestones of togetherness". Church News. Deseret News Inc. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- Embry, Jessie L. (April 1, 2001). "Crossing the Border: The Mormon Church and Mexico". Journal of the West. 40: 78–82.

- Brann, June (March 1996). "President Hinckley Encourages Texas Saints". Ensign Magazine. 26 (3).

- Nelson Russell, M. "Spiritual Treasures". 189th Semiannual General Conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 5 October 2019, Web,

- "What are Temples?". comeuntochrist.org. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- "Alkhair Islamic Society of RGV". Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- rocio (April 7, 2018). "Edinburg mosque hosts festival". The Monitor. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- "Bahá'ís of Mcallen, Texas". Bahá'í Faith. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- "Baha'i film To Be Shown Saturday at Downtowner". The Monitor (McAllen, TX). December 12, 1975. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- "Climate McAllen - Texas and Weather averages McAllen". www.usclimatedata.com. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- Treviño, Benjamin (November 4, 2018). "Winter Texan population continues to fluxuate". Brownsville Herald. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- National Park Service: Rancho de Carricitos

- "South Padre Island Travel Guide". U. S. News & World Report. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- "American Travelers Seek Cheaper Prescription Drugs In Mexico And Beyond". NPR.org. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- Rootstock and Scion Varieties by Julian W. Sauls, Professor & Extension Horticulturist, Texas AgriLife Extension

- "Here's How Trump's Border Wall Could Affect Ecotourism in the Rio Grande Valley". Texas Monthly. 2018-11-27. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- Woosnam, Kyle M; Dudensing, Rebekka M; Hanselka, Dan; An, Seonhee (September 1, 2011). "An Initial Examination of the Economic Impact of Nature Tourism on the Rio Grande Valley" (PDF). South Texas Nature Marketing Coop.

- "Cameron County Voter Registration Figures". www.sos.state.tx.us. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- "Texas Senators, Representatives, and Congressional District Maps". GovTrack.us. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- Fernandez, Manny (April 25, 2019). "South Texas Mayor Is Arrested on Election Fraud Charges, Fueling Bitter Political Fight". The New York Times. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- Ballí, Cecilia. "The Bad Guy With the Badge" (Archive). Texas Monthly. August 2006. Retrieved on May 25, 2016.

- Peschard-Sverdrup, Armand (January 7, 2003). U.S.-Mexico Transboundary Water Management: The Case of the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo (1 ed.). Center for Strategic & International Studies. ISBN 978-0892064243.

- Yardley, Jim (April 19, 2002). "Water Rights War Rages on Faltering Rio Grande". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Guido, Zack. "Drought on the Rio Grande". Climate.gov. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Texas | Full Senate results". www.cnn.com. Retrieved 2019-12-03.

- Porter, Charles Jesse (1940). Recreational Interests and Activities of High School Boys of the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press.

- Navarrete, Jose (September 1, 2018). "THE EVOLUTION OF BILINGUAL EDUCATION AND ITS SPILLOVER EFFECTS IN THE RIO GRANDE VALLEY". Journal of South Texas. 32: 136–147 – via Laredo College.

- Nájera, Jennifer R., 1975-. The borderlands of race : Mexican segregation in a South Texas town (First ed.). Austin. ISBN 9780292767560. OCLC 899987155.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- RAHC Vision Statement

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Rio Grande Valley. |

- Texas State Historical Association — Lower Rio Grande Valley

- Rio Grande Valley Partnership: Valley Chamber

- Rio Grande Valley Sports Information Center

- South Padre Island Turtle Cam

- Rgvattractions.com: Attractions in the Rio Grande Valley

- Rio Grande Valley Community Foundation

- RGVPride.com

- Los Ebanos, TX

- Wintertexaninfo.com: The Winter Texan Connection