Sugarcane

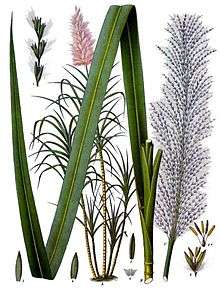

Sugarcane or sugar cane refer to several species and hybrids of tall perennial grasses in the genus Saccharum, tribe Andropogoneae, that are used for sugar production. The plants are two to six metres (six to twenty feet) tall with stout, jointed, fibrous stalks that are rich in sucrose, which accumulates in the stalk internodes. Sugarcanes belong to the grass family Poaceae, an economically important flowering plant family that includes maize, wheat, rice, and sorghum, and many forage crops. It is native to the warm temperate to tropical regions of Southeast Asia and New Guinea.

Sugarcane is the world's largest crop by production quantity, with 1.8 billion tonnes produced in 2017, with Brazil accounting for 40% of the world total. In 2012, the Food and Agriculture Organization estimated it was cultivated on about 26 million hectares (64 million acres), in more than 90 countries.

About 70% of the sugar produced globally comes from a species of sugarcane called Saccharum officinarum and hybrids of this species.[1] All sugarcane species can interbreed, and the major commercial cultivars are complex hybrids.[2]

Sugarcane accounts for 79% of sugar produced; most of the rest is made from sugar beets. While sugarcane predominantly grows in tropical and subtropical regions, sugar beets typically grow in colder temperate regions.

Sucrose (table sugar), extracted from sugarcane in specialized mill factories, is either used as raw material in the food industry or fermented to produce ethanol. Products derived from sugarcane include falernum, molasses, rum, cachaça, and bagasse. In some regions, people use sugarcane reeds to make pens, mats, screens, and thatch. The young, unexpanded flower head of Saccharum edule (duruka) is eaten raw, steamed, or toasted, and prepared in various ways in Southeast Asia, including Fiji and certain island communities of Indonesia.[3]

Sugarcane was an ancient crop of the Austronesian and Papuan people. It was introduced to Polynesia, Island Melanesia, and Madagascar in prehistoric times via Austronesian sailors. It was also introduced to southern China and India by Austronesian traders at around 1200 to 1000 BC. The Persians and Greeks encountered the famous "reeds that produce honey without bees" in India between the 6th and 4th centuries BC. They adopted and then spread sugarcane agriculture.[4] Merchants began to trade in sugar, which was considered a luxurious and expensive spice, from India. In the 18th century AD, sugarcane plantations began in Caribbean, South American, Indian Ocean and Pacific island nations and the need for laborers became a major driver of large migrations of people, some voluntarily accepting indentured servitude[5] and others forcibly exported as slaves.[6]

Etymology

The term "sugarcane" is a combination of two words; sugar and cane. The former meaning utimately derives from Sanskrit शर्करा (śárkarā) as the crop originated in Southeast Asia. As sugar was traded and spread West, this became سُكَّر (sukkar) in Arabic, zúccharo in Italian, zuccarum in Latin and eventually sucre in both Middle French and Middle English. The second term "cane" began to be used alongside it as the crop was grown on plantations in the Caribbean, this term is ultimately of Hebrew-origin from קנה (KaNeH) meaning "reed" or "stalk".[7] This term was introduced by Sephardic Jews in the 17th century in the French West Indies (Guadeloupe and Martinique), who spoke Judeo-Spanish and owned sugar plantations worked by their African slaves which produced sugarcane crop, until they were expelled by king Louis XIV in 1685 as part of the Code Noir.[8]

Description

Sugarcane is a tropical, perennial grass that forms lateral shoots at the base to produce multiple stems, typically 3 to 4 m (10 to 13 ft) high and about 5 cm (2 in) in diameter. The stems grow into cane stalk which, when mature, constitutes around 75% of the entire plant. A mature stalk is typically composed of 11–16% fiber, 12–16% soluble sugars, 2–3% non-sugars, and 63–73% water. A sugarcane crop is sensitive to climate, soil type, irrigation, fertilizers, insects, disease control, varieties, and the harvest period. The average yield of cane stalk is 60–70 tonnes per hectare (24–28 long ton/acre; 27–31 short ton/acre) per year. However, this figure can vary between 30 and 180 tonnes per hectare depending on knowledge and crop management approach used in sugarcane cultivation. Sugarcane is a cash crop, but it is also used as livestock fodder.[9]

History

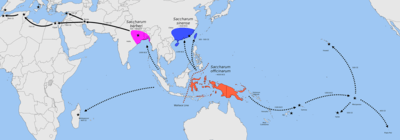

There are two centers of domestication for sugarcane: one for Saccharum officinarum by Papuans in New Guinea and another for Saccharum sinense by Austronesians in Taiwan and southern China. Papuans and Austronesians originally primarily used sugarcane as food for domesticated pigs. The spread of both S. officinarum and S. sinense is closely linked to the migrations of the Austronesian peoples. Saccharum barberi was only cultivated in India after the introduction of S. officinarum.[10][11]

Saccharum officinarum was first domesticated in New Guinea and the islands east of the Wallace Line by Papuans, where it is the modern center of diversity. Beginning around 6,000 BP they were selectively bred from the native Saccharum robustum. From New Guinea it spread westwards to maritime Southeast Asia after contact with Austronesians, where it hybridized with Saccharum spontaneum.[11]

The second domestication center is mainland southern China and Taiwan where S. sinense was a primary cultigen of the Austronesian peoples. Words for sugarcane exist in the Proto-Austronesian languages in Taiwan, reconstructed as *təbuS or **CebuS, which became *tebuh in Proto-Malayo-Polynesian. It was one of the original major crops of the Austronesian peoples from at least 5,500 BP. Introduction of the sweeter S. officinarum may have gradually replaced it throughout its cultivated range in maritime Southeast Asia.[13][14][12][15][16]

From Island Southeast Asia, S. officinarum was spread eastward into Polynesia and Micronesia by Austronesian voyagers as a canoe plant by around 3,500 BP. It was also spread westward and northward by around 3,000 BP to China and India by Austronesian traders, where it further hybridized with Saccharum sinense and Saccharum barberi. From there it spread further into western Eurasia and the Mediterranean.[11][12]

The earliest known production of crystalline sugar began in northern India. The exact date of the first cane sugar production is unclear. The earliest evidence of sugar production comes from ancient Sanskrit and Pali texts.[18][19][20][21] Around the 8th century, Muslim and Arab traders introduced sugar from medieval India to the other parts of the Abbasid Caliphate in the Mediterranean, Mesopotamia, Egypt, North Africa, and Andalusia. By the 10th century, sources state that every village in Mesopotamia grew sugarcane.[17] It was among the early crops brought to the Americas by the Spanish, mainly Andalusians, from their fields in the Canary Islands, and the Portuguese from their fields in the Madeira Islands.

Christopher Columbus first brought sugarcane to the Caribbean during his second voyage to the Americas; initially to the island of Hispaniola (modern day Haiti and the Dominican Republic). In colonial times, sugar formed one side of the triangle trade of New World raw materials, along with European manufactured goods, and African slaves. Sugar, often in the form of molasses, was shipped from the Caribbean to Europe or New England, where it was used to make rum. The profits from the sale of sugar were then used to purchase manufactured goods, which were then shipped to West Africa, where they were bartered for slaves. The slaves were then brought back to the Caribbean to be sold to sugar planters. The profits from the sale of the slaves were then used to buy more sugar, which was shipped to Europe.

%2C_plate_V_-_BL.jpg)

France found its sugarcane islands so valuable that it effectively traded its portion of Canada, famously dubbed "a few acres of snow", to Britain for their return of Guadeloupe, Martinique and St. Lucia at the end of the Seven Years' War. The Dutch similarly kept Suriname, a sugar colony in South America, instead of seeking the return of the New Netherlands (New York).

Boiling houses in the 17th through 19th centuries converted sugarcane juice into raw sugar. These houses were attached to sugar plantations in the Western colonies. Slaves often ran the boiling process under very poor conditions. Rectangular boxes of brick or stone served as furnaces, with an opening at the bottom to stoke the fire and remove ashes. At the top of each furnace were up to seven copper kettles or boilers, each one smaller and hotter than the previous one. The cane juice began in the largest kettle. The juice was then heated and lime added to remove impurities. The juice was skimmed and then channeled to successively smaller kettles. The last kettle, the "teache", was where the cane juice became syrup. The next step was a cooling trough, where the sugar crystals hardened around a sticky core of molasses. This raw sugar was then shoveled from the cooling trough into hogsheads (wooden barrels), and from there into the curing house.

In the British Empire, slaves were liberated after 1833 and many would no longer work on sugarcane plantations when they had a choice. British owners of sugarcane plantations therefore needed new workers, and they found cheap labour in China, Portugal and India.[22][23] The people were subject to indenture, a long-established form of contract which bound them to forced labour for a fixed term; apart from the fixed term of servitude, this resembled slavery.[24] The first ships carrying indentured labourers from India left in 1836.[25] The migrations to serve sugarcane plantations led to a significant number of ethnic Indians, southeast Asians and Chinese settling in various parts of the world.[26] In some islands and countries, the South Asian migrants now constitute between 10 and 50% of the population. Sugarcane plantations and Asian ethnic groups continue to thrive in countries such as Fiji, South Africa, Burma, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines, British Guiana, Jamaica, Trinidad, Martinique, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Grenada, St. Lucia, St. Vincent, St. Kitts, St. Croix, Suriname, Nevis, and Mauritius.[25][27]

Between 1863 and 1900, traders and plantation owners from the British colony of Queensland (now a state of Australia) brought between 55,000 and 62,500 people from the South Pacific Islands to work on sugarcane plantations. It is estimated that one-third of these workers were coerced or kidnapped into slavery (known as blackbirding). Many others were paid very low wages. Between 1904 and 1908, most of the 10,000 remaining workers were deported in an effort to keep Australia racially homogeneous and protect white workers from cheap foreign labour.[28]

Cuban sugar derived from sugarcane was exported to the USSR, where it received price supports and was ensured a guaranteed market. The 1991 dissolution of the Soviet state forced the closure of most of Cuba's sugar industry.

Sugarcane remains an important part of the economy of Guyana, Belize, Barbados, and Haiti, along with the Dominican Republic, Guadeloupe, Jamaica, and other islands.

About 70% of the sugar produced globally comes from S. officinarum and hybrids using this species.[1]

.jpg)

Cultivation

.jpg)

Sugarcane cultivation requires a tropical or subtropical climate, with a minimum of 60 cm (24 in) of annual moisture. It is one of the most efficient photosynthesizers in the plant kingdom. It is a C4 plant, able to convert up to 1% of incident solar energy into biomass.[29] In prime growing regions, such as Mauritius, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Peru, Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Guyana, Ecuador, Cuba, El Salvador, Jamaica, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia, and Australia, sugarcane crops can produce over 15 kg/m2 of cane. Once a major crop of the southeastern region of the United States, sugarcane cultivation declined there during the late 20th century, and is primarily confined to small plantations in Florida, Louisiana, and southeast Texas in the 21st century. Sugarcane cultivation ceased in Hawaii when the last operating sugar plantation in the state shut down in 2016.[30]

Sugarcane is cultivated in the tropics and subtropics in areas with a plentiful supply of water for a continuous period of more than six to seven months each year, either from natural rainfall or through irrigation. The crop does not tolerate severe frosts. Therefore, most of the world's sugarcane is grown between 22°N and 22°S, and some up to 33°N and 33°S.[31] When sugarcane crops are found outside this range, such as the Natal region of South Africa, it is normally due to anomalous climatic conditions in the region, such as warm ocean currents that sweep down the coast. In terms of altitude, sugarcane crops are found up to 1,600 metres or 5,200 feet close to the equator in countries such as Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru.[32]

Sugarcane can be grown on many soils ranging from highly fertile, well-drained Mollisols, through heavy cracking Vertisols, infertile acid Oxisols, peaty Histosols, to rocky Andisols. Both plentiful sunshine and water supplies increase cane production. This has made desert countries with good irrigation facilities such as Egypt some of the highest-yielding sugarcane-cultivating regions.

Although some sugarcanes produce seeds, modern stem cutting has become the most common reproduction method.[33] Each cutting must contain at least one bud, and the cuttings are sometimes hand-planted. In more technologically advanced countries like the United States and Australia, billet planting is common. Billets (stalks or stalk sections) harvested by a mechanical harvester are planted by a machine that opens and recloses the ground. Once planted, a stand can be harvested several times; after each harvest, the cane sends up new stalks, called ratoons. Successive harvests give decreasing yields, eventually justifying replanting. Two to 10 harvests are usually made depending on the type of culture. In a country with a mechanical agriculture looking for a high production of large fields, like in North America, sugar canes are replanted after two or three harvests to avoid a lowering in yields. In countries with a more traditional type of agriculture with smaller fields and hand harvesting, like in the French island la Réunion, sugar cane is often harvested up to 10 years before replanting.

Sugarcane is harvested by hand and mechanically. Hand harvesting accounts for more than half of production, and is dominant in the developing world. In hand harvesting, the field is first set on fire. The fire burns dry leaves, and chases away or kills venomous snakes, without harming the stalks and roots. Harvesters then cut the cane just above ground-level using cane knives or machetes. A skilled harvester can cut 500 kg (1,100 lb) of sugarcane per hour.

Mechanical harvesting uses a combine, or sugarcane harvester.[34] The Austoft 7000 series, the original modern harvester design, has now been copied by other companies, including Cameco / John Deere. The machine cuts the cane at the base of the stalk, strips the leaves, chops the cane into consistent lengths and deposits it into a transporter following alongside. The harvester then blows the trash back onto the field. Such machines can harvest 100 long tons (100 t) each hour; however, harvested cane must be rapidly processed. Once cut, sugarcane begins to lose its sugar content, and damage to the cane during mechanical harvesting accelerates this decline. This decline is offset because a modern chopper harvester can complete the harvest faster and more efficiently than hand cutting and loading. Austoft also developed a series of hydraulic high-lift infield transporters to work alongside their harvesters to allow even more rapid transfer of cane to, for example, the nearest railway siding. This mechanical harvesting does not require the field to be set on fire; the residue left in the field by the machine consists of sugar cane tops and dead leaves, which serve as mulch for the next planting.

Pests

The cane beetle (also known as cane grub) can substantially reduce crop yield by eating roots; it can be controlled with imidacloprid (Confidor) or chlorpyrifos (Lorsban). Other important pests are the larvae of some butterfly/moth species, including the turnip moth, the sugarcane borer (Diatraea saccharalis), the African sugarcane borer (Eldana saccharina), the Mexican rice borer (Eoreuma loftini), the African armyworm (Spodoptera exempta), leaf-cutting ants, termites, spittlebugs (especially Mahanarva fimbriolata and Deois flavopicta), and the beetle Migdolus fryanus. The planthopper insect Eumetopina flavipes acts as a virus vector, which causes the sugarcane disease ramu stunt.[35][36]

Pathogens

Numerous pathogens infect sugarcane, such as sugarcane grassy shoot disease caused by Phytoplasma, whiptail disease or sugarcane smut, pokkah boeng caused by Fusarium moniliforme, Xanthomonas axonopodis bacteria causes Gumming Disease, and red rot disease caused by Colletotrichum falcatum. Viral diseases affecting sugarcane include sugarcane mosaic virus, maize streak virus, and sugarcane yellow leaf virus.[37]

Nitrogen fixation

Some sugarcane varieties are capable of fixing atmospheric nitrogen in association with the bacterium Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus.[38] Unlike legumes and other nitrogen-fixing plants that form root nodules in the soil in association with bacteria, G. diazotrophicus lives within the intercellular spaces of the sugarcane's stem.[39][40] Coating seeds with the bacteria is a newly developed technology that can enable every crop species to fix nitrogen for its own use.[41]

Conditions for sugarcane workers

At least 20,000 people are estimated to have died of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in Central America in the past two decades – most of them sugar cane workers along the Pacific coast. This may be due to working long hours in the heat without adequate fluid intake.[42]

Processing

Traditionally, sugarcane processing requires two stages. Mills extract raw sugar from freshly harvested cane and "mill-white” sugar is sometimes produced immediately after the first stage at sugar-extraction mills, intended for local consumption. Sugar crystals appear naturally white in color during the crystallization process. Sulfur dioxide is added to inhibit the formation of color-inducing molecules as well as to stabilize the sugar juices during evaporation.[43][44] Refineries, often located nearer to consumers in North America, Europe, and Japan, then produce refined white sugar, which is 99% sucrose. These two stages are slowly merging. Increasing affluence in the sugar-producing tropics increased demand for refined sugar products, driving a trend toward combined milling and refining.

Milling

Sugarcane processing produces cane sugar (sucrose) from sugarcane. Other products of the processing include bagasse, molasses, and filtercake.

Bagasse, the residual dry fiber of the cane after cane juice has been extracted, is used for several purposes:[45]

- fuel for the boilers and kilns,

- production of paper, paperboard products, and reconstituted panelboard,

- agricultural mulch, and more,

- as a raw material for production of chemicals.

The primary use of bagasse and bagasse residue is as a fuel source for the boilers in the generation of process steam in sugar plants. Dried filtercake is used as an animal feed supplement, fertilizer, and source of sugarcane wax.

Molasses is produced in two forms: Blackstrap, which has a characteristic strong flavor, and a purer molasses syrup. Blackstrap molasses is sold as a food and dietary supplement. It is also a common ingredient in animal feed, is used to produce ethanol and rum, and in the manufacturing of citric acid. Purer molasses syrups are sold as molasses, and may also be blended with maple syrup, invert sugars, or corn syrup. Both forms of molasses are used in baking.

Refining

Sugar refining further purifies the raw sugar. It is first mixed with heavy syrup and then centrifuged in a process called "affination". Its purpose is to wash away the sugar crystals' outer coating, which is less pure than the crystal interior. The remaining sugar is then dissolved to make a syrup, about 60% solids by weight.

The sugar solution is clarified by the addition of phosphoric acid and calcium hydroxide, which combine to precipitate calcium phosphate. The calcium phosphate particles entrap some impurities and absorb others, and then float to the top of the tank, where they can be skimmed off. An alternative to this "phosphatation" technique is "carbonatation", which is similar, but uses carbon dioxide and calcium hydroxide to produce a calcium carbonate precipitate.

After filtering any remaining solids, the clarified syrup is decolorized by filtration through activated carbon. Bone char or coal-based activated carbon is traditionally used in this role.[46] Some remaining color-forming impurities are adsorbed by the carbon. The purified syrup is then concentrated to supersaturation and repeatedly crystallized in a vacuum, to produce white refined sugar. As in a sugar mill, the sugar crystals are separated from the molasses by centrifuging.[47] Additional sugar is recovered by blending the remaining syrup with the washings from affination and again crystallizing to produce brown sugar. When no more sugar can be economically recovered, the final molasses still contains 20–30% sucrose and 15–25% glucose and fructose.

To produce granulated sugar, in which individual grains do not clump, sugar must be dried, first by heating in a rotary dryer, and then by blowing cool air through it for several days.

Ribbon cane syrup

Ribbon cane is a subtropical type that was once widely grown in the southern United States, as far north as coastal North Carolina. The juice was extracted with horse or mule-powered crushers; the juice was boiled, like maple syrup, in a flat pan, and then used in the syrup form as a food sweetener.[48] It is not currently a commercial crop, but a few growers find ready sales for their product.

Pollution from sugarcane processing

Particulate matter, combustion products, and volatile organic compounds are the primary pollutants emitted during the sugarcane processing.[45] Combustion products include nitrogen oxides (NOX), carbon monoxide (CO), CO2, and sulfur oxides (SOX). Potential emission sources include the sugar granulators, sugar conveying and packaging equipment, bulk loadout operations, boilers, granular carbon and char regeneration kilns, regenerated adsorbent transport systems, kilns and handling equipment (at some facilities), carbonation tanks, multi-effect evaporator stations, and vacuum boiling pans. Modern pollution prevention technologies are capable of addressing all of these potential pollutants.

Production

| Sugarcane production in 2018 | |

|---|---|

| millions of tonnes | |

Global production of sugarcane in 2018 was 1.91 billion tonnes, with Brazil producing 39% of the world total, India with 20%, and China and Thailand producing about 6% each (table).

Worldwide, 26 million hectares were devoted to sugarcane cultivation in 2018.[49] The average worldwide yield of sugarcane crops in 2018 was 73 tonnes per hectare, led by Peru with 121 tonnes per hectare.[49] The theoretical possible yield for sugarcane is about 280 tonnes per hectare per year, and small experimental plots in Brazil have demonstrated yields of 236–280 tonnes of cane per hectare.[50][51]

Ethanol

Ethanol is generally available as a byproduct of sugar production. It can be used as a biofuel alternative to gasoline, and is widely used in cars in Brazil. It is an alternative to gasoline, and may become the primary product of sugarcane processing, rather than sugar.

In Brazil, gasoline is required to contain at least 22% bioethanol.[52] This bioethanol is sourced from Brazil's large sugarcane crop.

The production of ethanol from sugar cane is more energy efficient than from corn or sugar beets or palm/vegetable oils, particularly if cane bagasse is used to produce heat and power for the process. Furthermore, if biofuels are used for crop production and transport, the fossil energy input needed for each ethanol energy unit can be very low. EIA estimates that with an integrated sugar cane to ethanol technology, the well-to-wheels CO2 emissions can be 90% lower than conventional gasoline.[52]

A textbook on renewable energy[53] describes the energy transformation:

Presently, 75 tons of raw sugar cane are produced annually per hectare in Brazil. The cane delivered to the processing plant is called burned and cropped (b&c), and represents 77% of the mass of the raw cane. The reason for this reduction is that the stalks are separated from the leaves (which are burned and whose ashes are left in the field as fertilizer), and from the roots that remain in the ground to sprout for the next crop. Average cane production is, therefore, 58 tons of b&c per hectare per year.

Each ton of b&c yields 740 kg of juice (135 kg of sucrose and 605 kg of water) and 260 kg of moist bagasse (130 kg of dry bagasse). Since the lower heating value of sucrose is 16.5 MJ/kg, and that of the bagasse is 19.2 MJ/kg, the total heating value of a ton of b&c is 4.7 GJ of which 2.2 GJ come from the sucrose and 2.5 from the bagasse.

Per hectare per year, the biomass produced corresponds to 0.27 TJ. This is equivalent to 0.86 W per square meter. Assuming an average insolation of 225 W per square meter, the photosynthetic efficiency of sugar cane is 0.38%.

The 135 kg of sucrose found in 1 ton of b&c are transformed into 70 litres of ethanol with a combustion energy of 1.7 GJ. The practical sucrose-ethanol conversion efficiency is, therefore, 76% (compare with the theoretical 97%).

One hectare of sugar cane yields 4,000 litres of ethanol per year (without any additional energy input, because the bagasse produced exceeds the amount needed to distill the final product). This, however, does not include the energy used in tilling, transportation, and so on. Thus, the solar energy-to-ethanol conversion efficiency is 0.13%.

Bagasse applications

Sugarcane is a major crop in many countries. It is one of the plants with the highest bioconversion efficiency. Sugarcane crop is able to efficiently fix solar energy, yielding some 55 tonnes of dry matter per hectare of land annually. After harvest, the crop produces sugar juice and bagasse, the fibrous dry matter. This dry matter is biomass with potential as fuel for energy production. Bagasse can also be used as an alternative source of pulp for paper production.[54]

Sugarcane bagasse is a potentially abundant source of energy for large producers of sugarcane, such as Brazil, India and China. According to one report, with use of latest technologies, bagasse produced annually in Brazil has the potential of meeting 20% of Brazil's energy consumption by 2020.[55]

Electricity production

A number of countries, in particular those lacking fossil fuels, have implemented energy conservation and efficiency measures to minimize the energy used in cane processing and export any excess electricity to the grid. Bagasse is usually burned to produce steam, which in turn creates electricity. Current technologies, such as those in use in Mauritius, produce over 100 kWh of electricity per tonne of bagasse. With a total world harvest of over one billion tonnes of sugar cane per year, the global energy potential from bagasse is over 100,000 GWh.[56] Using Mauritius as a reference, an annual potential of 10,000 GWh of additional electricity could be produced throughout Africa.[57] Electrical generation from bagasse could become quite important, particularly to the rural populations of sugarcane producing nations.

Recent cogeneration technology plants are being designed to produce from 200 to over 300 kWh of electricity per tonne of bagasse.[58][59] As sugarcane is a seasonal crop, shortly after harvest the supply of bagasse would peak, requiring power generation plants to strategically manage the storage of bagasse.

Sugarcane as food

Freshly squeezed sugarcane juice | |

| Nutritional value per 100 grams | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 242 kJ (58 kcal) |

13.11 g | |

| Sugars | 12.85 g |

| Dietary fiber | 0.56 g |

0.40 | |

0.16 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin B6 | 31% 0.40 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 11% 44.53 μg |

| Vitamin C | 8% 6.73 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 2% 18 mg |

| Iron | 9% 1.12 mg |

| Magnesium | 4% 13.03 mg |

| Phosphorus | 3% 22.08 mg |

| Potassium | 3% 150 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 1.16 mg |

| Zinc | 1% 0.14 mg |

Nutrient Information from Indian Food Composition Database | |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

In most countries where sugarcane is cultivated, there are several foods and popular dishes derived directly from it, such as:

- Raw sugarcane: chewed to extract the juice

- Sayur nganten: an Indonesian soup made with the stem of trubuk (Saccharum edule), a type of sugarcane.

- Sugarcane juice: a combination of fresh juice, extracted by hand or small mills, with a touch of lemon and ice to make a popular drink, known variously as air tebu, usacha rass, guarab, guarapa, guarapo, papelón, aseer asab, ganna sharbat, mosto, caldo de cana, nước miá.

- Syrup: a traditional sweetener in soft drinks, now largely supplanted in the US by high fructose corn syrup, which is less expensive because of corn subsidies and sugar tariffs.[61]

- Molasses: used as a sweetener and a syrup accompanying other foods, such as cheese or cookies

- Jaggery: a solidified molasses, known as gur, gud, or gul in India, is traditionally produced by evaporating juice to make a thick sludge, and then cooling and molding it in buckets. Modern production partially freeze dries the juice to reduce caramelization and lighten its color. It is used as sweetener in cooking traditional entrees, sweets and desserts.

- Falernum: a sweet, and slightly alcoholic drink made from sugarcane juice

- Cachaça: the most popular distilled alcoholic beverage in Brazil; a liquor made of the distillation of sugarcane juice.

- Rum: is a liquor made from sugarcane products, typically molasses but sometimes also cane juice. It is most commonly produced in the Caribbean and environs.

- Basi: is a fermented alcoholic beverage made from sugarcane juice produced in the Philippines and Guyana.

- Panela: solid pieces of sucrose and fructose obtained from the boiling and evaporation of sugarcane juice; a food staple in Colombia and other countries in South and Central America

- Rapadura: a sweet flour that is one of the simplest refinings of sugarcane juice, common in Latin American countries such as Brazil, Argentina and Venezuela (where it is known as papelón) and the Caribbean.

- Rock candy: crystallized cane juice

- Gâteau de Sirop

Sugarcane as feed

Many parts of the sugarcane are commonly used as animal feeds where the plants are cultivated. The leaves make a good forage for ruminants.[62]

Gallery

Sugar cane harvested by women, Hòa Bình Province, Vietnam

Sugar cane harvested by women, Hòa Bình Province, Vietnam Evaporator with baffled pan and foam dipper for making ribbon cane syrup

Evaporator with baffled pan and foam dipper for making ribbon cane syrup Sugarcane and bowl of refined sugar

Sugarcane and bowl of refined sugar Caipirinha, a cocktail made from sugarcane-derived Cachaça

Caipirinha, a cocktail made from sugarcane-derived Cachaça

See also

References

- "Plants & Fungi: Saccharum officinarum (sugar cane)". Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 2012-06-04.

- Vilela, Mariane de Mendonça; Del-Bem, Luiz-Eduardo; Van Sluys, Marie-Anne; De Setta, Nathalia; Kitajima, João Paulo; et al. (2017). "Analysis of Three Sugarcane Homo/Homeologous Regions Suggests Independent Polyploidization Events of Saccharum officinarum and Saccharum spontaneum". Genome Biology and Evolution. 9 (2): 266–278. doi:10.1093/gbe/evw293. PMC 5381655. PMID 28082603.

- "Consumer Preference for Indigenous Vegetables" (PDF). World Agroforestry Centre. 2009.

- "Agribusiness Handbook: Sugar beet white sugar" (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization, United Nations. 2009.

- "Indian indentured labourers". The National Archives, Government of the United Kingdom. 2010.

- Mintz, Sidney (1986). Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-009233-2.

- Mozeson, Isaac (2000). The Word: The Dictionary That Reveals the Hebrew Source of English. SP Books. p. 40. ISBN 1561719420.

- "The Judeo-Spanish origin of sugar cane". The Times of Israel. 10 September 2019.

- Perez, Rena (1997). "Chapter 3: Sugar cane". Feeding pigs in the tropics. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- Daniels, John; Daniels, Christian (April 1993). "Sugarcane in Prehistory". Archaeology in Oceania. 28 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4453.1993.tb00309.x.

- Paterson, Andrew H.; Moore, Paul H.; Tom L., Tew (2012). "The Gene Pool of Saccharum Species and Their Improvement". In Paterson, Andrew H. (ed.). Genomics of the Saccharinae. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 43–72. ISBN 9781441959478.

- Daniels, Christian; Menzies, Nicholas K. (1996). Needham, Joseph (ed.). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 6, Biology and Biological Technology, Part 3, Agro-Industries and Forestry. Cambridge University Press. pp. 177–185. ISBN 9780521419994.

- Blust, Robert (1984–1985). "The Austronesian Homeland: A Linguistic Perspective". Asian Perspectives. 26 (1): 44–67. hdl:10125/16918.

- Spriggs, Matthew (2 January 2015). "Archaeology and the Austronesian expansion: where are we now?". Antiquity. 85 (328): 510–528. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00067910.

- Aljanabi, Salah M. (1998). "Genetics, phylogenetics, and comparative genetics of Saccharum L., a polysomic polyploid Poales: Andropogoneae". In El-Gewely, M. Raafat (ed.). Biotechnology Annual Review. 4. Elsevier Science B.V. pp. 285–320. ISBN 9780444829719.

- Baldick, Julian (2013). Ancient Religions of the Austronesian World: From Australasia to Taiwan. I.B.Tauris. p. 2. ISBN 9780857733573.

- Watson, Andrew (1983). Agricultural innovation in the early Islamic world. Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 9780521247115

- Watt, George (1893), The Economic Products of India, W. H. Allen & Co., Vol 6, Part II, pp. 29–30

- Hill, J.A. (1902), The Anglo-American Encyclopedia, Vol. 7, p. 725

- Luckey, Thomas D. (1973) CRC Handbook of Food Additives, 2nd edition, Furia, Thomas E. (ed.) Vol. 1, Ch. 1. p. 7. ISBN 978-0849305429

- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2004) Encyclopedia of Kitchen History, Routledge, pp. 145–146. ISBN 978-1579583804

- Lai, Walton (1993). Indentured labor, Caribbean sugar: Chinese and Indian migrants to the British West Indies, 1838–1918. ISBN 978-0-8018-7746-9.

- Vertovik, Steven (1995). Robin Cohen (ed.). The Cambridge survey of world migration. pp. 57–68. ISBN 978-0-521-44405-7.

- Tinker, Hugh (1993). New System of Slavery. Hansib Publishing, London. ISBN 978-1-870518-18-5.

- "Forced Labour". The National Archives, Government of the United Kingdom. 2010.

- Laurence, K (1994). A Question of Labour: Indentured Immigration Into Trinidad & British Guiana, 1875–1917. St Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-12172-3.

- "St. Lucia's Indian Arrival Day". Caribbean Repeating Islands. 2009.

- Flanagan, Tracey; Wilkie, Meredith; Iuliano, Susanna. "Australian South Sea Islanders: A century of race discrimination under Australian law". Australian Human Rights Commission. Archived from the original on 2011-03-14.

- Whitmarsh, John (1999). "The Photosynthetic Process". In GS Singhal, G Renger, SK Sopory, K-D Irrgang and Govindjee (ed.). Concepts in Photobiology: Photosynthesis and Photomorphogenesis. Narosa Publishers/New Delhi and Kluwer Academic/Dordrecht. pp. 11–51. ISBN 978-9401060264.CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)

- Solomon, Molly (17 December 2016). "The final days of Hawaiian sugar". US National Public Radio – Hawaii. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Rolph, George (1873). Something about sugar: its history, growth, manufacture and distribution. San Francisco, J. J. Newbegin.

- Griffee, Peter (2000). "Saccharum Officinarum". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Bassam, Nasir El (2010). Handbook of Bioenergy Crops: A Complete Reference to Species, Development and Applications. Earthscan. ISBN 9781849774789.

- "Sugar-Cane Harvester Cuts Forty-Tons an Hour". Popular Mechanics Monthly. Hearst Magazines. July 1930. Retrieved 2012-04-02.

- Malein, Patrick. "How to find brand-new diseases of sugarcane!". Biological Sciences at Oxford. Archived from the original on August 11, 2007.

- Odiyo, Peter Onyango (December 1981). "Development of the first outbreaks of the African armyworm, Spodoptera exempta (Walk.), between Kenya and Tanzania during the 'off-season' months of July to December". International Journal of Tropical Insect Science. 1 (4): 305–318. doi:10.1017/S1742758400000606. S2CID 85994702.

- Gonçalves, Marcos; Pinto, Luciana; Creste, Silvana; Landell, Marcos (9 November 2011). "Virus Diseases of Sugarcane. A Constant Challenge to Sugarcane Breeding in Brazil". Functional Plant Science & Biotechnology. 6: 108–116.

- Yamada, Y.; Hoshino, K.; Ishikawa, T. (1998). "Gluconacetobacter corrig.‡ (Gluconoacetobacter [sic]). In Validation of Publication of New Names and New Combinations Previously Effectively Published Outside the IJSB, List no. 64" (PDF). Int J Syst Bacteriol. 48 (1): 327–328. doi:10.1099/00207713-48-1-327. Retrieved 2020-03-13.

- Dong, Z.; et al. (1994). "A Nitrogen-Fixing Endophyte of Sugarcane Stems (A New Role for the Apoplast)". Plant Physiology. 105 (4): 1139–1147. doi:10.1104/pp.105.4.1139. PMC 159442. PMID 12232271.

- Boddey, R. M.; Urquiaga, S.; Reis, V.; Döbereiner, J. (November 1991). "Biological nitrogen fixation associated with sugar cane". Plant and Soil. 137 (1): 111–117. doi:10.1007/BF02187441. S2CID 27437118.

- Cocking, E. C.; Stone, P. J.; Davey, M. R. (2006). "Intracellular colonization of roots of Arabidopsis and crop plants by Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus". In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology - Plant. 42: 74–82. doi:10.1079/IVP2005716. S2CID 24642832.

- Lakhani, Nina (16 February 2015). "Nicaraguans demand action over illness killing thousands of sugar cane workers". The Guardian. Retrieved 2015-04-09.

- Steindl, Roderick (2005). "Syrup Clarification for Plantation White Sugar to meet New Quality Standards" (PDF). In Hogarth, DM (ed.). Proceedings of the XXV Congress of International Society of Sugar Cane Technologists. Guatemala, Guatemala City. pp. 106–116.

- CODEX Standard for Sugars (PDF) (Report).

- "Sugarcane processing" (PDF). Environmental Protection Agency, United States. 2005.

- Yacoubou, Jeanne (2007). "Is Your Sugar Vegan? An Update on Sugar Processing Practices" (PDF). Vegetarian Journal. Vol. 26 no. 4. pp. 15–19. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- "Find out How Brer Rabbit Molasses is Made". Brer Rabbit. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- Cowser, R. L. (Jan–Mar 1978). "Cooking Ribbon Cane Syrup". The Kentucky Folklore Record.

- "Sugarcane production in 2017, Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity (pick lists)". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2019. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- Bogden AV (1977). Tropical Pasture and Fodder Plants (Tropical Agriculture). Longman Group (Far East), Limited. ISBN 978-0582466760.

- Duke, James (1983). "Saccharum officinarum L." Purdue University.

- "IEA Energy Technology Essentials: Biofuel Production" (PDF). International Energy Agency. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-15. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- da Rosa, A. (2005) Fundamentals of Renewable Energy Processes. Elsevier. pp. 501–502. ISBN 978-0-12-088510-7

- Rainey, Thomas; Covey, Geoff; Shore, Dennis (December 2006). "An analysis of Australian sugarcane regions for bagasse paper manufacture". International Sugar Journal. 108 (1295): 640–644.

- "Cetrel and Novozymes to Make Biogas and Electricity from Bagasse". Business Wire. 14 December 2009.

- "Wade Report on Global Bagasse Cogeneration: High Efficiency Bagasse Cogeneration Can Meet Up To 25% of National Dower Demand in Cane Producing Countries" (PDF) (Press release). World Alliance for Decentralized Energy. 15 June 2004. Retrieved 2020-03-13.

Bagasse Cogen – Global Review and Potential (Report). World Alliance for Decentralized Energy. 2004. - "Sugar Cane Bagasse Energy Cogeneration – Lessons from Mauritius" (PDF). The United Nations. 2005.

- "Steam economy and cogeneration in cane sugar factories" (PDF). International Sugar Journal. 92 (1099): 131–140. 1990. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-24.

- Hollanda, Erber (2010). Trade and Environment Review. United Nations. pp. 68–80. ISBN 978-92-1-112782-9.

- "Indian Food Composition Tables". National Institute of Nutrition, Indian Council of Medical Research. 2017.

- Pollan M (12 October 2003). "The (Agri)Cultural Contradictions Of Obesity". The New York Times.

- Heuzé, V.; Thiollet, H.; Tran, G.; Lebas, F. (5 July 2018). "Sugarcane forage, whole plant". Feedipedia, a programme by INRA, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sugar cane. |

| Look up sugarcane in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |