Ogaden War

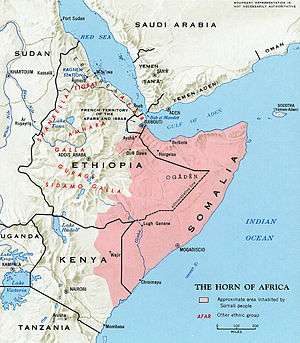

The Ogaden War, or the Ethio-Somali war (Somali: Dagaalkii Xoraynta Soomaali Galbeed), was a Somali military offensive between July 1977 and March 1978 over the disputed Ethiopian region of Ogaden, which began with the Somali invasion of Ethiopia.[25] The Soviet Union disapproved of the invasion and ceased its support of Somalia, instead starting to support Ethiopia. Ethiopia was saved from a major defeat and a permanent loss of territory through a massive airlift of military supplies worth $1 billion, the arrival of 16,000 Cuban troops sent by Fidel Castro to win a second African victory (after his first success in Angola in 1975–76),[20] and 1,500 Soviet advisors, led by General Vasily Petrov. The Ethiopians and Cubans prevailed at Harar, Dire Dawa and Jijiga, and began to push the Somalis systematically out of the Ogaden. By March 1978, the Ethiopians and Cubans had captured almost all of the Ogaden, prompting the defeated Somalis to give up their claim to the region.[26] The Somalis took a terrible beating from Cuban artillery and aerial assaults.[27] A third of the initial Somali National Army invasion force was killed, and half of the Somali Airforce destroyed; the war left Somalia with a disorganized and demoralized army and an angry population. All of these conditions led to a revolt in the army which eventually spiraled into a civil war.[28]

Background

Territorial partition

Following World War II, Britain retained control of both British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland as protectorates. In 1950, as a result of the Paris Peace Treaties, the United Nations granted Italy trusteeship of Italian Somaliland, but only under close supervision and on the condition—first proposed by the Somali Youth League (SYL) and other nascent Somali political organizations, such as Hizbia Digil Mirifle Somali (HDMS) and the Somali National League (SNL)—that Somalia achieve independence within ten years.[29][30] British Somaliland remained a protectorate of Britain until 1960.[31][32]

In 1948, under pressure from their World War II allies and to the dismay of the Somalis,[33] the British returned the Haud (an important Somali grazing area that was presumably 'protected' by British treaties with the Somalis in 1884 and 1886) and the Ogaden to Ethiopia, based on a treaty they signed in 1897 in which the British, French and Italians agreed upon the territorial boundaries of Ethiopia with the Ethiopian Emperor Menelik in exchange for his help against raids by hostile clans.[34] Britain included the provision that the Somali residents would retain their autonomy, but Ethiopia immediately claimed sovereignty over the area.[29] This prompted an unsuccessful bid by Britain in 1956 to buy back the Somali lands it had turned over.[29] Britain also granted administration of the almost exclusively Somali-inhabited[35] Northern Frontier District (NFD) to Kenyan nationalists despite an informal plebiscite demonstrating the overwhelming desire of the region's population to join the newly formed Somali Republic.[36]

A referendum was held in neighboring Djibouti (then known as French Somaliland) in 1958, on the eve of Somalia's independence in 1960, to decide whether or not to join the Somali Republic or to remain with France. The referendum turned out in favour of a continued association with France, largely due to a combined yes vote by the sizable Afar ethnic group and resident Europeans.[37] There was also widespread vote rigging, with the French expelling thousands of Somalis before the referendum reached the polls.[38] The majority of those who voted no were Somalis who were strongly in favour of joining a united Somalia, as had been proposed by Mahmoud Harbi, Vice President of the Government Council. Harbi was killed in a plane crash two years later.[37] Djibouti finally gained its independence from France in 1977, and Hassan Gouled Aptidon, who had campaigned for a yes vote in the referendum of 1958, eventually wound up as Djibouti's first president (1977–1991).[37]

British Somaliland became independent on 26 June 1960 as the State of Somaliland, and the Trust Territory of Somalia (the former Italian Somaliland) followed suit five days later.[39] On July 1, 1960, the two territories united to form the Somali Republic.[40][41] A government was formed by Abdullahi Issa and other members of the trusteeship and protectorate governments, with Haji Bashir Ismail Yusuf as President of the Somali National Assembly, Aden Abdullah Osman Daar as President of the Somali Republic and Abdirashid Ali Shermarke as Prime Minister (later to become President from 1967–1969). On 20 July 1961, through a popular referendum, the people of Somalia ratified a new constitution that had been first drafted the previous year.[42]

On 15 October 1969, while paying a visit to the northern town of Las Anod, Somalia's then President Shermarke was shot dead by one of his own bodyguards. His assassination was quickly followed by a military coup d'état on 21 October 1969 (the day after his funeral), in which the Somali Army seized power without encountering armed opposition—essentially a bloodless takeover. The coup was spearheaded by Major General Mohamed Siad Barre, who at the time commanded the army.[43]

Supreme Revolutionary Council

Alongside Barre, the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) that assumed power after President Sharmarke's assassination was led by Lieutenant Colonel Salaad Gabeyre Kediye and Chief of Police Jama Korshel. Kediye officially held the title of "Father of the Revolution", and Barre shortly afterwards became the head of the SRC.[44] The SRC subsequently renamed the country the Somali Democratic Republic,[45][46] dissolved the parliament and the Supreme Court, and suspended the constitution.[47]

In addition to previous Soviet funding and arms support to Somalia, Egypt sent millions of dollars in arms to Somalia, established military training and sent experts to Somalia in support of Egypt's long standing policy of securing the Nile River flow by destabilising Ethiopia.

Somali National Army Plan

Under the leadership of General Mohamed Ali Samatar, Irro and other senior Somali military officials were mandated in 1977 with formulating a national strategy in preparation for the Ogaden campaign in Ethiopia.[48] This was part of a broader effort to unite all of the Somali-inhabited territories in the Horn region into a Greater Somalia (Soomaaliweyn).[49]

A distinguished graduate of Frunze, Samantar oversaw Somalia's military strategy. In the late 1970s, Samatar was the Chief Commanding Officer of the Somali National Army during the Ogaden Campaign.[48] He and his frontline deputies faced off against their mentor and former Frunze alumni Marshal Vasily Ivanovich Petrov, who was assigned by the USSR to advise the Ethiopian Army, in addition to 15,000 Cuban troops supporting Ethiopia,[50] led by General Arnaldo Ochoa.[51] The Ogaden Campaign was part of a broader effort to unite all of the Somali-inhabited territories in the Horn region into a Greater Somalia (Soomaaliweyn).[49] General Samatar was assisted in the offensive by several field commanders, most of whom were also Frunze graduates:[52]

General Yussuf Salhan commanded SNA in Jigjiga Front assisted by Col. A. Naji, capturing the area on August 30, 1977. (Later became Minister of Tourism. Salhan was eventually expelt from the Somali Socialist Party in 1985)

Col. Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed commanded SNA in Negellie Front. (Later the leader of SSDF Rebel group, arrested by Mengistu and released by EPRDF in 1991)

Col. Abdullahi Ahmed Irro commanded SNA in the Godey Front. (Retired Somali and became a Professor of Strategy in Mogadishu Somalia)

Col. Ali Hussein commanded SNA in two front's, Qabri Dahare and Harrar. (Eventually joined the SNM late 1988)

Col. Farah Handulle commanded SNA in the Warder Front. (Became a civilian administrator and Governor of Sanaag, later killed in Hargheisa as the new appointed Governor of Hargheisa in 1987 one day before he took over the Governorship)

General Mohamed Nur Galaal assisted by Col.Mohamud Sh. Abdullahi Geelqaad commanded Dirir-Dewa. The SNA retreated from Dirir-Dewa. ( Galaal became Minister of Public Works and Leading member of the ruling Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party)

Col. Abdulrahman Aare led the Degeh-Bur Front. (Later chosen to reinforce the Harar campaign; eventually became a military attache and retired as a private citizen after the collapse of SNA in 1990)

Col. Abukar Liban 'Aftooje' commanded the SNA in the Iimeey Front. (Later became a General and a military attache to France).

Derg

As Somalia gained military strength, Ethiopia grew weaker. In September 1974, Emperor Haile Selassie had been overthrown by the Derg (the military council), marking a period of turmoil. The Derg quickly fell into internal conflict to determine who would have primacy. Meanwhile, various anti-Derg as well as separatist movements began throughout the country. The regional balance of power now favoured Somalia.

One of the separatist groups seeking to take advantage of the chaos was the pro-Somalia Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF) operating in the Somali-inhabited Ogaden area, which by late 1975 had struck numerous government outposts. WSLF had control of most of the Ogaden, the first time since the Second World War that all Somalia was united with the exception of the NFD region in Kenya. The victory in Ogaden was mostly because of support from the Harari populace who had aligned with the WSLF.[53] From 1976 to 1977, Somalia supplied arms and other aid to the WSLF.

A sign that order had been restored among the Derg was the announcement of Mengistu Haile Mariam as head of state on February 11, 1977. However, the country remained in chaos as the military attempted to suppress its civilian opponents in a period known as the Red Terror (or Qey Shibir in Amharic). Despite the violence, the Soviet Union, which had been closely observing developments, came to believe that Ethiopia was developing into a genuine Marxist–Leninist state and that it was in Soviet interests to aid the new regime. They thus secretly approached Mengistu with offers of aid that he accepted. Ethiopia closed the U.S. military mission and the communications centre in April 1977.

In June 1977, Mengistu accused Somalia of infiltrating SNA soldiers into the Somali area to fight alongside the WSLF. Despite considerable evidence to the contrary, Barre strongly denied this, saying SNA "volunteers" were being allowed to help the WSLF.

Castro siding with Ethiopia

When the Cubans and the Soviets learned of the Somali plans to annex the Ogaden, Castro flew to Aden in March 1977 where he suggested an Ethiopian-Somali-Yemeni Socialist Federation. Castro's plan didn't get any support and two months later Somali forces attacked the Ethiopians. Cuba, supported by troops from the USSR and South Yemen, sided with Ethiopia.[54][55][56]

Course of the war

Invasion and Initial stage (July–August)

The Somali National Army committed to invade the Ogaden on July 12, 1977, according to Ethiopian Ministry of National Defense documents (some other sources state July 13[57] or 23 July).[58] According to Ethiopian sources, the invaders numbered 70,000 troops, 40 fighter planes, 250 tanks, 350 APCs, and 600 artillery, which would have meant practically the whole Somali Army.[57] By the end of the month 60% of the Ogaden had been taken by the SNA-WSLF force, including Gode, on the Shabelle River. The attacking forces did suffer some early setbacks; Ethiopian defenders at Dire Dawa and Jijiga inflicted heavy casualties on assaulting forces. The Ethiopian Air Force (EAF) also began to establish air superiority using its Northrop F-5s, despite being initially outnumbered by Somali MiG-21s. However, Somalia was easily overpowering Ethiopian military hardware and technology capability. Army-general Vasily Petrov of the Soviet Armed Forces had to report back to Moscow the "sorry state" of the Ethiopian Army. The 3rd and 4th Ethiopian Infantry Divisions that suffered the brunt of the Somali invasion had practically ceased to exist.[59]

The USSR, finding itself supplying both sides of a war, attempted to mediate a ceasefire. When their efforts failed, the Soviets abandoned Somalia. All aid to Siad Barre's regime was halted, while arms shipments to Ethiopia were increased. Soviet military aid (second in magnitude only to the October 1973 gigantic resupplying of Syrian forces during the Yom Kippur War) and advisors flooded into the country along with around 15,000 Cuban combat troops. Other communist countries offered assistance: the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen offered military assistance and North Korea helped train a "People's Militia"; East Germany likewise offered training, engineering and support troops.[7] (As the scale of communist assistance became clear in November 1977, Somalia broke diplomatic relations with the USSR and expelled all Soviet citizens from the country.)

Not all communist states sided with Ethiopia. Because of the Sino-Soviet rivalry, China supported Somalia diplomatically and with token military aid.[60][61] Romania under Nicolae Ceauşescu had a habit of breaking with Soviet policies and maintained good diplomatic relations with Siad Barre.

By 17 August elements of the Somali Army had reached the outskirts of the strategic city of Dire Dawa. Not only was the country's second largest military airbase located here, as well as Ethiopia's crossroads into the Ogaden, but Ethiopia's rail lifeline to the Red Sea ran through this city, and if the Somalis held Dire Dawa, Ethiopia would be unable to export its crops or bring in equipment needed to continue the fight. Gebre Tareke estimates the Somalis advanced with two motorized brigades, one tank battalion and one BM battery upon the city; against them were the Ethiopian Second Militia Division, the 201 Nebelbal battalion, 781 battalion of the 78th Brigade, the 4th Mechanized Company, and a tank platoon possessing two tanks.[62] The fighting was vicious as both sides knew what the stakes were, but after two days, despite that the Somalis had gained possession of the airport at one point, the Ethiopians had repulsed the assault, forcing the Somalis to withdraw. Henceforth, Dire Dawa was never at risk of attack.[63]

Somali victories and siege of Harar (September–January)

The greatest single victory of the SNA-WSLF was a second assault on Jijiga in mid-September (the Battle of Jijiga), in which the demoralized Ethiopian troops withdrew from the town. The local defenders were no match for the assaulting Somalis and the Ethiopian military was forced to withdraw past the strategic strongpoint of the Marda Pass, halfway between Jijiga and Harar. By September Ethiopia was forced to admit that it controlled only about 10% of the Ogaden and that the Ethiopian defenders had been pushed back into the non-Somali areas of Harerge, Bale, and Sidamo. However, the Somalis were unable to press their advantage because of the high attrition on its tank battalions, constant Ethiopian air attacks on their supply lines, and the onset of the rainy season which made the dirt roads unusable. During that time, the Ethiopian government managed to raise and train a giant militia force 100,000 strong and integrated it into the regular fighting force. Also, since the Ethiopian army was a client of U.S weapons, hasty acclimatization to the new Warsaw Pact bloc weaponry took place.

From October 1977 until January 1978, the SNA-WSLF forces attempted to capture Harar during the Battle of Harar, where 40,000 Ethiopians had regrouped and re-armed with Soviet-supplied artillery and armor; backed by 1500 Soviet "advisors" and 11,000 Cuban soldiers, they engaged the attackers in vicious fighting. Though the Somali forces reached the city outskirts by November, they were too exhausted to take the city and eventually had to withdraw to await the Ethiopian counterattack.

Ethiopian-Cuban counter-attack (February–March)

.jpg)

The expected Ethiopian-Cuban attack occurred in early February; however, it was accompanied by a second attack that the Somalis did not expect. A column of Ethiopian and Cuban troops crossed northeast into the highlands between Jijiga and the border with Somalia, bypassing the SNA-WSLF force defending the Marda Pass. Mil Mi-6 helicopters airlifted Cuban BMD-1 and ASU-57 armored vehicles behind enemy lines. The Somali defense collapsed and every major Somali town was recaptured in the following weeks. Recognizing that his position was untenable, Siad Barre ordered the SNA to retreat back into Somalia on 9 March 1978, although Rene LaFort claims that the Somalis, having foreseen the inevitable, had already withdrawn their heavy weapons.[64] The last significant Somali unit left Ethiopia on 15 March 1978, marking the end of the war.

Effects of the war

Following the withdrawal of the SNA, the WSLF continued their insurgency. By May 1980, the rebels, with the assistance of a small number of SNA soldiers who continued to help the guerrilla war, controlled a substantial region of the Ogaden. However, by 1981 the insurgents were reduced to sporadic hit-and-run attacks and were finally defeated. In addition, the WSLF and SALF were significantly weakened after the Ogaden War. The former was practically defunct by the late 1980s, with its splinter group, the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) operating from headquarters in Kuwait. Even though elements of the ONLF would later manage to slip back into the Ogaden, their actions had little impact.[65]

For the Barre regime, the invasion was perhaps the greatest strategic blunder since independence,[66] and it weakened the military. Almost one-third of the regular SNA soldiers, three-eighths of the armored units and half of the Somali Air Force (SAF) were lost. The weakness of the Barre administration led it to effectively abandon the dream of a unified Greater Somalia. The failure of the war aggravated discontent with the Barre regime; the first organized opposition group, the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF), was formed by army officers in 1979.

The United States adopted Somalia as a Cold War ally from the late 1970s to 1988 in exchange for use of Somali bases, and a way to exert influence upon the region. A second armed clash in 1988 was resolved when the two countries agreed to withdraw their militaries from the border.

See also

- Soviet Union-Africa relations#Ethiopia

References

Notes

- Ayele 2014, p. 106: "MOND classified documents reveal that the full-scale Somali invasion came on Tuesday, July 12, 1991. The date of the invasion was not, therefore, July 13 or July 23 as some authors have claimed."

- Lapidoth, Ruth (1982). The Read Sea and the Gulf of Aden. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

- Marxist Governments_ A World Survey_ Mozambique-Yugoslavia. p. 656.

- Crockatt 1995, p. 283.

- Gorman 1981, p. 208

- "North Korea's Military Partners in the Horn". The Diplomat. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- "Ethiopia: East Germany". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 2004-10-29.

- Tareke 2000, p. 648.

- Tareke 2009, pp. 204–5.

- Tareke 2000, p. 656.

- Tareke 2000, p. 638.

- Halliday & Molyneux 1982, p. 14.

- Gleijeses, Piero (2013). Visions of Freedom: Havana, Washington, Pretoria and the Struggle for Southern Africa, 1976-1991. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-4696-0968-3.

- White, Matthew (2011). Atrocities: The 100 Deadliest Episodes in Human History. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-08330-9.

- Tareke 2000, p. 640.

- Tareke 2000, p. 665.

- Tareke 2000, p. 664.

- Clodfelter 2017, p. 566.

- Cooper, Tom (2015). Wings over Ogaden: The Ethiopian–Somali War, 1978–1979. Helion and Company. p. 58.

- Clodfelter 2017, p. 557.

- Krivosheev, G.F. (2001). "Russia and the USSR in the wars of the 20th century, statistical study of armed forces' losses (in Russian)". Soldat.ru. Archived from the original on 2008-01-29. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- Fragile States and Insecure People?: Violence, Security, and Statehood in the Twenty-First Century. Springer. 2007. p. 73.

- http://gadaa.com/06142007002.pdf Evil Days: Thirty Years of War and Famine in Ethiopia

- Evil Days: Thirty Years of War and Famine in Ethiopia

- Tareke 2009, p. 186.

- Ephrem, Yared. "Ethiopian-Somali War Over the Ogaden". www.blackpast.org. University of Washington. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- Kirk, J.; Erisman, H. Michael (2009). Cuban Medical Internationalism: Origins, Evolution, and Goals. Springer. p. 75.

- "The Rise and Fall of Somalia". stratfor.com. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- Zolberg, Aristide R., et al., Escape from Violence: Conflict and the Refugee Crisis in the Developing World, (Oxford University Press: 1992), p. 106

- Kwame Anthony Appiah; Henry Louis Gates (26 November 2003). Africana: the encyclopedia of the African and African American experience: the concise desk reference. Running Press. p. 1749. ISBN 978-0-7624-1642-4.

- Paolo Tripodi (1999). The colonial legacy in Somalia: Rome and Mogadishu: from colonial administration to Operation Restore Hope. Macmillan Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-312-22393-9.

- https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=S7FuMAEACAAJ&dq=ogaden+war&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj2zPm9rtrZAhWlL8AKHeDuBUEQ6AEILzAB

- Federal Research Division, Somalia: A Country Study, (Kessinger Publishing, LLC: 2004), p. 38

- Laitin, p. 73

- Francis Vallat, First report on succession of states in respect of treaties: International Law Commission twenty-sixth session 6 May – 26 July 1974, (United Nations: 1974), p. 20

- Laitin, p. 75

- Barrington, Lowell, After Independence: Making and Protecting the Nation in Postcolonial and Postcommunist States, (University of Michigan Press: 2006), p. 115

- Kevin Shillington, Encyclopedia of African history, (CRC Press: 2005), p. 360.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, The New Encyclopædia Britannica, (Encyclopædia Britannica: 2002), p. 835

- "The dawn of the Somali nation-state in 1960". Buluugleey.com. Archived from the original on January 16, 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- "The making of a Somalia state". Strategypage.com. 2006-08-09. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- Greystone Press Staff, The Illustrated Library of The World and Its Peoples: Africa, North and East, (Greystone Press: 1967), p. 338

- Moshe Y. Sachs, Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Volume 2, (Worldmark Press: 1988), p. 290.

- Adam, Hussein Mohamed; Richard Ford (1997). Mending rips in the sky: options for Somali communities in the 21st century. Red Sea Press. p. 226. ISBN 1-56902-073-6.

- J. D. Fage, Roland Anthony Oliver, The Cambridge history of Africa, Volume 8, (Cambridge University Press: 1985), p. 478.

- The Encyclopedia Americana: complete in thirty volumes. Skin to Sumac, Volume 25, (Grolier: 1995), p. 214.

- Peter John de la Fosse Wiles, The New Communist Third World: an essay in political economy, (Taylor & Francis: 1982), p. 279 ISBN 0-7099-2709-6.

- Abdul Ahmed III (29 October 2011). "Brothers in Arms Part I" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2012.

- Lewis, I.M.; The Royal African Society (October 1989). "The Ogaden and the Fragility of Somali Segmentary Nationalism". African Affairs. 88 (353): 573–579. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a098217. JSTOR 723037.

- Lockyer, Adam. "Opposing Foreign Intervention's Impact on the Course of Civil Wars: The Ethiopian-Ogaden Civil War, 1976-1980" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Payne, Richard J. (1988). Opportunities and Dangers of Soviet-Cuban Expansion: Toward a Pragmatic U.S. Policy. SUNY Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0887067969.

- Ahmed III, Abdul. "Brothers in Arms Part II" (PDF). WardheerNews. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- Matshanda, Namhla (2014). Centres in the Periphery: Negotiating Territoriality and Identification in Harar and Jijiga from 1942 (PDF). The University of Edinburgh. p. 200.

- "Fidel Castro Left Mark on Somalia, Horn of Africa". Voice of America. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- defenceresearch (2019-02-19). "THE BATTLE FOR THE HORN OF AFRICA: A RETROSPECTIVE". Defence-In-Depth. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- "68. Ethiopia/Ogaden (1948-present)". uca.edu. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- Tareke 2000, p. 644.

- Ayele 2014, p. 106.

- Urban 1983, p. 42.

- "Russians in Somalia: Foothold in Africa Suddenly Shaky". New York Times. 1977-09-16. Retrieved 2020-01-05.

- "the ogaden situation" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2020-01-05.

- Tareke 2000, p. 645.

- Tareke 2000, p. 646.

- Lefort 1983, p. 260.

- Belete Belachew Yihun (2014). "Ethiopian foreign policy and the Ogaden War: the shift from "containment" to "destabilization," 1977–1991". Journal of Eastern African Studies. 8 (4). doi:10.1080/17531055.2014.947469. The version at samaynta.com lacks references.

- Tareke 2009, p. 214.

Bibliography

- Crockatt, Richard (1995). The Fifty Years War: The United States and the Soviet Union in World Politics. London & New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-10471-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gebru Tareke (2000). "The Ethiopia-Somalia War of 1977 Revisited" (PDF). International Journal of African Historical Studies. 33 (3): 635–667. JSTOR 3097438.

- ——— (2009). The Ethiopian Revolution: War in the Horn of Africa. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14163-4.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Gorman, Robert F. (1981). Political Conflict on the Horn of Africa. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-030-59471-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halliday, Fred; Molyneux, Maxine (1982). "Ethiopia's Revolution from Above". MERIP Reports (106): 5–15. JSTOR 3011492.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lefort, René (1983). Ethiopia: An Heretical Revolution?. London: Zed Press. ISBN 978-0-862-32154-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Urban, Mark (1983). "Soviet intervention and the Ogaden counter-offensive of 1978". RUSI Journal. 128 (2): 42–46. doi:10.1080/03071848308523524.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ayele, Fantahun (2014). The Ethiopian Army: From Victory to Collapse, 1977-1991. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 9780810130111.

- Woodroofe, Louise P. "Buried in the Sands of the Ogaden": The United States, the Horn of Africa, and the Demise of Detente (Kent State University Press; 2013) 176 pages.

- Clodfelter, M. (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015 (4th ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0786474707.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Cooper, Tom. "Ogaden War, 1977-1978". Air Combat Information Group (www.acig.org). Archived from the original on 2007-01-07. Retrieved 2007-03-18. External link in

|publisher=(help) - Ogaden War 1976–1978 at OnWar.com

- at GlobalSecurity.org

- Cuban Aviation at the Ogaden War

- Adam Lockyer, Opposing Foreign Intervention’s Impact on the Course of Civil Wars: the Ethiopian-Ogaden Civil War, 1976-1980