Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill[1] (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965)[2] was a British politician, army officer, and writer. He was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945, when he led the country to victory in the Second World War, and again from 1951 to 1955. Apart from two years between 1922 and 1924, Churchill was a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1900 to 1964 and represented a total of five constituencies. Ideologically an economic liberal and imperialist, he was for most of his career a member of the Conservative Party, as leader from 1940 to 1955. He was a member of the Liberal Party from 1904 to 1924.

Sir Winston Churchill | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 26 October 1951 – 5 April 1955 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Anthony Eden | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Clement Attlee | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Anthony Eden | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 May 1940 – 26 July 1945 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George VI | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Clement Attlee (1942–1945) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Neville Chamberlain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Clement Attlee | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father of the House of Commons | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 8 October 1959 – 25 September 1964 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | David Grenfell | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Rab Butler | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill 30 November 1874 Blenheim, Oxfordshire, England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 24 January 1965 (aged 90) Kensington, London, England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | St Martin's Church, Bladon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Civilian awards | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allegiance | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1893–1924 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | See list | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Commands | 6th Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military awards | See list | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Of mixed English and American parentage, Churchill was born in Oxfordshire to a wealthy, aristocratic family. He joined the British Army in 1895, and saw action in British India, the Anglo-Sudan War, and the Second Boer War, gaining fame as a war correspondent and writing books about his campaigns. Elected an MP in 1900, initially as a Conservative, he defected to the Liberals in 1904. In H. H. Asquith's Liberal government, Churchill served as President of the Board of Trade, Home Secretary, and First Lord of the Admiralty, championing prison reform and workers' social security. As First Lord during the First World War, he oversaw the Gallipoli Campaign; after it proved a disaster, he resigned from government and served in the Royal Scots Fusiliers on the Western Front. In 1917, he returned to government under David Lloyd George and served successively as Minister of Munitions, Secretary of State for War, Secretary of State for Air, and Secretary of State for the Colonies, overseeing the Anglo-Irish Treaty and British foreign policy in the Middle East. After two years out of Parliament, he served as Chancellor of the Exchequer in Stanley Baldwin's Conservative government, returning the pound sterling in 1925 to the gold standard at its pre-war parity, a move widely seen as creating deflationary pressure and depressing the UK economy.

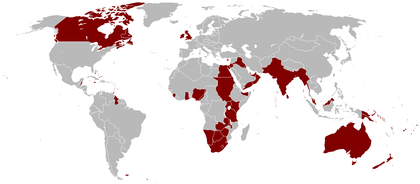

Out of office during the 1930s, Churchill took the lead in calling for British rearmament to counter the growing threat of militarism in Nazi Germany. At the outbreak of the Second World War he was re-appointed First Lord of the Admiralty. In 1940 he became prime minister, replacing Neville Chamberlain. Churchill oversaw British involvement in the Allied war effort against the Axis powers, resulting in victory in 1945. After the Conservatives' defeat in the 1945 general election, he became Leader of the Opposition. Amid the developing Cold War with the Soviet Union, he publicly warned of an "iron curtain" of Soviet influence in Europe and promoted European unity. Re-elected Prime Minister in 1951, his second term was preoccupied with foreign affairs, especially Anglo-American relations and, despite ongoing decolonisation, preservation of the British Empire. Domestically, his government emphasised house-building and developed a nuclear weapon. In declining health, Churchill resigned as prime minister in 1955, although he remained an MP until 1964. Upon his death in 1965, he was given a state funeral.

Widely considered one of the 20th century's most significant figures, Churchill remains popular in the UK and Western world, where he is seen as a victorious wartime leader who played an important role in defending Europe's liberal democracy from the spread of fascism. Also praised as a social reformer and writer, among his many awards was the Nobel Prize in Literature. Conversely, his imperialist views and comments on race have generated controversy. He has been widely criticised for some wartime events, notably the 1945 bombing of Dresden and the perceived inadequacy of his government's response to the Bengal Famine of 1943.

Early life

Childhood and schooling: 1874–1895

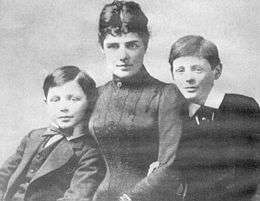

Churchill was born at his family's ancestral home, Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire, on 30 November 1874.[4] As direct descendants of the Dukes of Marlborough, his family were among the highest levels of the British aristocracy,[5] and thus he was born into the country's governing elite.[6] His father, Lord Randolph Churchill, had been elected Conservative MP for Woodstock in 1873.[7] His mother, Jennie, was a daughter of Leonard Jerome, a wealthy American businessman.[8] The couple had married in April 1874,[9] and, according to the biographer Sebastian Haffner, were "rich by normal standards but poor by those of the rich".[10]

In 1876, Churchill's paternal grandfather, John Spencer-Churchill, was appointed Viceroy of Ireland, then part of the United Kingdom. Randolph became his private secretary, resulting in the family's relocation to Dublin.[11] Winston's brother, Jack, was born there in 1880.[12] Throughout much of the 1880s, Randolph and Jennie were effectively estranged,[13] and the brothers were mostly cared for by their nanny, Elizabeth Everest.[14] Churchill later wrote that "she had been my dearest and most intimate friend during the whole of the twenty years I had lived".[15]

Churchill began boarding at St. George's School in Ascot, Berkshire at age seven but was not academic and his behaviour was poor.[16] In 1884 he transferred to Brunswick School in Hove, where his academic performance improved.[17] In April 1888, aged 13, he narrowly passed the entrance exam for Harrow School.[18] There, his academics proved high but his teachers again complained about his lack of discipline;[19] his poetry appeared in the Harrovian school magazine.[20] His father wanted him to prepare for a military career and so his last three years at Harrow were in the army form.[21] After two unsuccessful attempts to gain admittance to the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, he succeeded on his third attempt.[22] He was accepted as a cadet in the cavalry, starting in September 1893.[23] His father died in January 1895, soon after Churchill finished at Sandhurst; this led Churchill to adopt the belief that members of his family inevitably died young.[24]

Cuba, India, and Sudan: 1895–1899

In February 1895, Churchill was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the 4th Queen's Own Hussars regiment of the British Army, based at Aldershot.[25] Eager to witness military action, Churchill used his mother's influence to try to get himself posted to a war zone.[26] In the autumn of 1895, he and Reginald Barnes went to Cuba to observe its war of independence and became involved in skirmishes after joining Spanish troops attempting to suppress independence fighters.[27] He proceeded to New York City, staying with the wealthy politician Bourke Cockran, who became a profound influence.[28] Churchill admired the United States, writing to his mother about "what an extraordinary people the Americans are!"[29] With the Hussars, Churchill then arrived in Bombay, British India, in October 1896.[30] Basing himself in Bangalore, he stayed in India for 19 months, visiting Calcutta three times and joining expeditions to Hyderabad and the North West Frontier.[31]

Churchill began a project of self-education while in India,[33] reading a range of authors including Plato, Adam Smith, Charles Darwin, Henry Hallam, Edward Gibbon, Winwood Reade, and Thomas Babington Macaulay.[34] Interested in British parliamentary affairs,[35] he declared himself "a Liberal in all but name" but added that he could never endorse the Liberal Party's support for Irish home rule.[36] Instead he allied himself to the Tory democracy wing of the Conservative Party, and on a visit home, gave his first public speech for the party's Primrose League in Bath.[37] Mixing reformist and conservative perspectives, he supported the promotion of secular, non-denominational education while opposing women's suffrage.[38]

Churchill volunteered to join Bindon Blood's Malakand Field Force in its campaign against Mohmand rebels in the Swat Valley of north-west India. Blood accepted him on condition that he was assigned as a journalist, the beginning of Churchill's writing career; he filed reports for The Pioneer and The Daily Telegraph.[39] He returned to Bangalore in October 1897 and there wrote his first book, The Story of the Malakand Field Force, which received positive reviews.[40] He also wrote his only work of fiction, Savrola, a roman à clef set in an imagined Balkan kingdom. It was serialised in Macmillan's Magazine in 1899 before appearing in book form.[41]

Despite some reluctance by General Herbert Kitchener, who saw him as a glory-hunter, Churchill leveraged his contacts in London—including Prime Minister Lord Salisbury—to obtain a posting to Kitchener's campaign in the Sudan as a journalist for The Morning Post.[42] Churchill joined the 21st Lancers in Cairo and subsequently took an active part in the Battle of Omdurman.[43] Churchill was critical of Kitchener's actions during the war, particularly the latter's unmerciful treatment of enemy wounded and his desecration of Muhammad Ahmad's tomb in Omdurman.[44] Following the battle, Churchill gave skin from his chest for a graft for an injured officer.[45] He returned to England and wrote The River War, an account of the campaign published in November 1899.[46]

Politics and South Africa: 1899–1901

Seeking a parliamentary career, Churchill pursued political contacts and gave addresses at Conservative meetings.[48] He was selected as one of the party's two parliamentary candidates at the June 1899 by-election in Oldham, Lancashire.[49] While campaigning in Oldham, Churchill referred to himself as "a Conservative and a Tory Democrat".[50] Although the Oldham seats had previously been held by the Conservatives, the election was a narrow Liberal victory.[51] During this period, he had courted Pamela Plowden, with whom he remained a lifelong friend,[52] and made a return visit to India, during which he stayed in the home of Viceroy George Nathaniel Curzon.[53] En route home, he spent two weeks in Cairo, where he met the Khedive Abbas II.[54]

Anticipating the outbreak of the Second Boer War between Britain and the Boer Republics, Churchill sailed to South Africa as a journalist for the Daily Mail and Morning Post.[55] In October he travelled to the conflict zone near Ladysmith, then besieged by Boer troops, before heading for Colenso.[56] After his train was derailed by Boer artillery shelling, he was captured as a prisoner of war (POW) and interned in a Boer POW camp in Pretoria.[57] In December, Churchill escaped the prison, stowing away aboard freight trains and hiding in a mine to evade his captors. He eventually made it to safety in Portuguese East Africa.[58] His escape attracted much publicity in Britain.[59]

In January 1900 he was appointed a lieutenant in the South African Light Horse regiment, joining Redvers Buller's fight to relieve the Siege of Ladysmith and take Pretoria.[60] He was among the first British troops into Ladysmith and Pretoria. He and his cousin, the Duke of Marlborough, demanded and received the surrender of 52 Boer prison camp guards.[61] Throughout the war, he had publicly chastised anti-Boer prejudices, calling for them to be treated with "generosity and tolerance",[62] and after the war he urged the British to be magnanimous in victory.[63] In July he returned to Britain, where his Morning Post despatches had been published as London to Ladysmith via Pretoria and had sold well.[64]

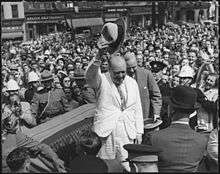

Churchill rented a flat in London's Mayfair, using it as his base for the next six years. He stood again as one of the Conservative candidates at Oldham in the October 1900 general election, securing a narrow victory to become an MP at age 25.[65] In the same month, he published Ian Hamilton's March, a book about his South African experiences,[66][67] which became the focus of a lecture tour in November through Britain, America and Canada. MPs were unpaid and the tour was a financial necessity. In America, Churchill met Mark Twain, President McKinley and Vice President Theodore Roosevelt; he did not get on well with Roosevelt.[68] In spring 1901 he gave more lectures in Paris, Madrid and Gibraltar.[69]

Conservative MP: 1901–1904

.jpg)

In February 1901, Churchill took his seat in the House of Commons, where his maiden speech gained widespread press coverage.[70] He associated with a group of Conservatives known as the Hughligans,[71] although was critical of the Conservative government on various issues. He condemned the British execution of a Boer military commandant,[72] and voiced concerns about the levels of public expenditure;[73] in response, Prime Minister Arthur Balfour asked him to join a parliamentary select committee on the topic.[74] He opposed increases to army funding, suggesting that any additional military expenditure should go to the navy.[75] This upset the Conservative front bench but gained support from Liberals.[76] He increasingly socialised with senior Liberals, particularly Liberal Imperialists like H. H. Asquith.[76] In this context, he later wrote, he "drifted steadily to the left" of British parliamentary politics.[72] He privately considered "the gradual creation by an evolutionary process of a Democratic or Progressive wing to the Conservative Party",[77] or alternately a "Central Party" to unite the Conservatives and Liberals.[78]

By 1903, Churchill was increasingly dissatisfied with the Conservatives, in part due to their promotion of economic protectionism, but also because he had attracted the animosity of many party members and was likely aware that this might have prevented him gaining a Cabinet position under a Conservative government. The Liberal Party was then attracting growing support, and so his defection in 1904 may have also have been influenced by personal ambition.[79] In a 1903 letter, he referred to himself as an "English Liberal ... I hate the Tory party, their men, their words and their methods".[80] In the House of Commons, he increasingly voted with the Liberal opposition against the government.[81] In February 1903, Churchill was among 18 Conservative MPs who voted against the government's increase in military expenditure.[82] He backed the Liberal vote of censure against the use of Chinese indentured labourers in South Africa, and in favour of a Liberal bill to restore legal rights to trade unions.[81] His April 1904 parliamentary speech upholding the rights of trade unions was described by the pro-Conservative Daily Mail as "Radicalism of the reddest type".[83] In May 1903, Joseph Chamberlain, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, called for the introduction of tariffs on goods imported into the British Empire from outside; Churchill became a leading Conservative voice against such economic protectionism.[84] Describing himself as a "sober admirer" of "the principles of Free Trade",[85] in July he was a founding member of the anti-protectionist Free Food League.[86] In October, Balfour's government sided with Chamberlain and announced protectionist legislation.[87]

Churchill's outspoken criticism of Balfour's government and imperial protectionism, coupled with a letter of support he sent to a Liberal candidate in Ludlow, angered many Conservatives.[88] In December 1903, the Oldham Conservative Association informed him that it would not support his candidature in the next general election.[89] In March 1904, Balfour and the Conservative front bench walked out of the House of Commons during one of his speeches.[90] In May he expressed opposition to the government's proposed Aliens Bill, which was designed to curb Jewish migration into Britain.[91] He stated that the bill would "appeal to insular prejudice against foreigners, to racial prejudice against Jews, and to labour prejudice against competition" and expressed himself in favour of "the old tolerant and generous practice of free entry and asylum to which this country has so long adhered and from which it has so greatly gained".[91] On 31 May 1904, he crossed the floor, defecting from the Conservatives to sit as a member of the Liberal Party in the House of Commons.[92]

Liberal MP: 1904–1908

.jpg)

In December 1905, Balfour resigned as Prime Minister and King Edward VII invited the Liberal leader Henry Campbell-Bannerman to take his place.[93] Hoping to secure a working majority in the House of Commons, Campbell-Bannerman called a general election for January 1906, which the Liberals won.[94] Having had a previous invitation from the Manchester Liberals to stand in their constituency,[95] Churchill did so, winning the Manchester North West seat.[96] January also saw the publication of Churchill's biography of his father;[97] he received an advance payment of £8000 for the book, the highest ever paid for a political biography in Britain to that point.[98] It was generally well received.[99] It was also at this time that the first biography of Churchill himself, written by the Liberal Alexander MacCallum Scott, was published.[100]

In the new government, Churchill became Under-Secretary of State for the Colonial Office, a position that he had requested.[101] He worked beneath the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Victor Bruce, 9th Earl of Elgin,[102] and took Edward Marsh as his secretary; the latter remained Churchill's secretary for 25 years.[103] In this junior ministerial position, Churchill was first tasked with helping to draft a constitution for the Transvaal.[104] In 1906, he helped oversee the granting of a government to the Orange Free State.[105] In dealing with southern Africa, he sought to ensure equality between the British and Boer.[106] He also announced a gradual phasing out of the use of Chinese indentured labourers in South Africa; he and the government decided that a sudden ban would cause too much upset in the colony and might damage the economy.[107] He expressed concerns about the relations between European settlers and the black African population; after Zulu launched the Bambatha Rebellion in Natal, he complained of Europeans' "disgusting butchery of the natives".[108]

In August 1906, Churchill holidayed on a yacht in Deauville, France, spending much of his time playing polo or gambling.[109] From there he proceeded to Paris and then Switzerland—where he climbed the Eggishorn—and then to Berlin and Silesia, where he was a guest of Kaiser Wilhelm II.[110] He went then to Venice, and from there toured Italy by motorcar with his friend, Lionel Rothschild.[111] In May 1907, he holidayed at the home of another friend, Maurice de Forest, in Biarritz.[112] In the autumn, he embarked on a tour of Europe and Africa.[112] He travelled through France, Italy, Malta, and Cyprus, before moving through the Suez Canal to Aden and Berbera.[113] Sailing to Mombasa, he travelled by rail through the Kenya Colony—stopping for big game hunting in Simba—before heading through the Uganda Protectorate and then sailing up the River Nile.[114] He wrote about his experiences for Strand Magazine and later published them in book form as My African Journey.[115]

Asquith government: 1908–1915

President of the Board of Trade: 1908–1910

_with_fianc%C3%A9e_Clementine_Hozier_(1885-1977)_shortly_before_their_marriage_in_1908.jpg)

When Asquith succeeded Campbell-Bannerman in 1908, Churchill was promoted to the Cabinet as President of the Board of Trade.[116] Aged 33, he was the youngest Cabinet member since 1866.[117] Newly appointed Cabinet ministers were legally obliged to seek re-election at a by-election; in April, Churchill lost the Manchester North West by-election to the Conservative candidate by 429 votes.[118] The Liberals then stood him in a by-election in the Scottish safe seat of Dundee, where he won comfortably.[119] In his Cabinet role, Churchill worked with Liberal politician David Lloyd George to champion social reform.[120] In one speech Churchill stated that although the "vanguard" of the British people "enjoys all the delights of all the ages, our rearguard struggles out into conditions which are crueller than barbarism".[121] To deal with this, he promoted what he called a "network of State intervention and regulation" akin to that in Germany.[122] His speeches on these issues were published in the volumes Liberalism and the Social Problem and The People's Rights.[123]

One of the first tasks he faced was in arbitrating an industrial dispute among ship-workers and their employers on the River Tyne.[124] He then established a Standing Court of Arbitration to deal with future industrial disputes,[125] establishing a reputation as a conciliator.[126] Arguing that workers should have their working hours reduced, Churchill promoted the Mines Eight Hours Bill—which legally prohibited miners working more than an eight-hour day—introducing its second reading in the House of Commons.[127] In 1908, he introduced the Trade Boards Bill to parliament, which would establish a Board of Trade which could prosecute exploitative employers, establish the principle of minimum wage, and the right of workers to have meal breaks. The bill passed with a large majority.[128] In May, he proposed the Labour Exchanges Bill which sought to establish over 200 Labour Exchanges through which the unemployed would be assisted in finding employment.[129] He also promoted the idea of an unemployment insurance scheme, which would be part-funded by the state.[130]

To ensure funding for these social reforms, he and Lloyd George denounced Reginald McKennas' expansion of warship production.[131] Churchill openly ridiculed those who thought war with Germany was inevitable[132]—according to biographer Roy Jenkins he was going through "a pro-German phase"[133]—and in autumn 1909 he visited Germany, spending time with the Kaiser and observing German Army manoeuvres.[134]

In his personal life, Churchill proposed marriage to Clementine Hozier;[135] they were married in September at St Margaret's, Westminster.[136] They honeymooned in Baveno, Venice, and Veverí Castle in Moravia;[137] before settling into a London home at 33 Eccleston Square.[138] The following July they had a daughter, Diana.[139]

To pass its social reforms into law, Asquith's Liberal government presented them in the form of the People's Budget.[140] Conservative opponents of the reform set up the Budget Protest League; supporters of it established the Budget League, of which Churchill became president.[141] The budget passed in the House of Commons but was rejected by the Conservative peers who dominated the House of Lords; this threatened Churchill's social reforms.[142] Churchill warned that such upper-class obstruction would anger working-class Britons and could lead to class war.[143] To deal with the deadlock, the government called a January 1910 general election, which resulted in a narrow Liberal victory; Churchill retained his seat at Dundee.[144] After the election, he proposed the abolition of the House of Lords in a cabinet memorandum, suggesting that it be replaced either by a unicameral system or by a new, smaller second chamber that lacked an in-built advantage for the Conservatives.[145] In April, the Lords relented and the budget was passed.[146]

Home Secretary: 1910–1911

—Winston Churchill in the House of Commons, 1910[147]

In February 1910, Churchill was promoted to Home Secretary, giving him control over the police and prison services,[148] and he implemented a prison reform programme.[149] He introduced a distinction between criminal and political prisoners, with prison rules for the latter being relaxed.[150] He tried to establish libraries for prisoners,[151] and introduced a measure ensuring that each prison must put on either a lecture or a concert for the entertainment of prisoners four times a year.[152] He reduced the length of solitary confinement for first offenders to one month and for recidivists to three months,[153] and spoke out against what he regarded as the excessively lengthy sentences meted out to perpetrators of certain crimes.[154] He proposed the abolition of automatic imprisonment of those who failed to pay fines,[155] and put a stop to the imprisonment of those aged between 16 and 21 except in cases where they had committed the most serious offences.[156] Of the 43 capital sentences passed while he was Home Secretary, he commuted 21 of them.[157]

One of the major domestic issues in Britain was that of women's suffrage. By this point, Churchill supported giving women the vote, although would only back a bill to that effect if it had majority support from the (male) electorate.[158] His proposed solution was a referendum on the issue, but this found no favour with Asquith and women's suffrage remained unresolved until 1918.[159] Many Suffragettes took Churchill for a committed opponent of women's suffrage,[160] and targeted his meetings for protest.[159] In November 1910, the suffragist Hugh Franklin attacked Churchill with a whip; Franklin was arrested and imprisoned for six weeks.[160]

In the summer of 1910, Churchill spent two months on de Forest's yacht in the Mediterranean.[161] Back in Britain, he was tasked with dealing with the Tonypandy Riot, in which coal miners in the Rhondda Valley violently protested against their working conditions.[162] The Chief Constable of Glamorgan requested troops to help police quell the rioting. Churchill, learning that the troops were already travelling, allowed them to go as far as Swindon and Cardiff, but blocked their deployment; he was concerned that the use of troops could lead to bloodshed. Instead he sent 270 London police—who were not equipped with firearms—to assist their Welsh counterparts.[163] As the riots continued, he offered the protesters an interview with the government's chief industrial arbitrator, which they accepted.[164] Privately, Churchill regarded both the mine owners and striking miners as being "very unreasonable".[160] The Times and other media outlets accused him of being too soft on the rioters;[165] conversely, many in the Labour Party, which was linked to the trade unions, regarded him as having been too heavy-handed.[166]

Asquith called a general election for December 1910, in which the Liberals were re-elected and Churchill again secured his Dundee seat.[167] In January 1911, Churchill became involved with the Siege of Sidney Street; three Latvian burglars had killed several police officers and hidden in a house in London's East End, which was surrounded by police.[168] Churchill joined the police although did not direct their operation.[169] After the house caught on fire, he told the fire brigade not to proceed into the house because of the threat that the armed Latvians posed to them. After the event, two of the burglars were found dead.[169] Although he faced criticism for his decision, he stated that he "thought it better to let the house burn down rather than spend good British lives in rescuing those ferocious rascals".[170]

In March 1911, he introduced the second reading of the Coal Mines Bill to parliament, which—when implemented into law—introduced stricter safety standards to coal mines.[171] He also formulated the Shops Bill to improve the working conditions of shop workers; it faced opposition from shop owners and only passed into law in a much emasculated form.[172] To maintain pressure on this issue, he became president of the Early Closing Association and remained in that position until the early 1940s.[173] In April, Lloyd George introduced the first health and unemployment insurance legislation, the National Insurance Act 1911; Churchill had been instrumental in drafting it.[172] In May, his wife gave birth to their second child, Randolph, named after Churchill's father.[174] In 1911, he was tasked with dealing with escalating civil strife, sending troops into Liverpool to quell protesting dockers and rallying against a national railway strike.[175] As the Agadir Crisis emerged, which threatened the outbreak of war between Germany and France, Churchill suggested that—should negotiations fail—the UK should form an alliance with France and Russia and safeguard the independence of Belgium, the Netherlands, and Denmark in the face of possible German expansionism.[176] The Agadir Crisis had a dramatic effect on Churchill and his views about the need for naval expansion.[177]

First Lord of the Admiralty

In October 1911, Asquith appointed Churchill First Lord of the Admiralty.[178] He settled into his official London residence at Admiralty House,[179] and established his new office aboard the admiralty yacht, the Enchantress.[180] Over the next two and a half years he focused on naval preparation, visiting naval stations and dockyards, seeking to improve naval morale, and scrutinising German naval developments.[181] After the German government passed the German Navy Law to increase warship production, Churchill vowed that Britain would do the same and that for every new battleship built by the Germans, Britain would build two.[182] Believing an oligarchy of "the landlord ascendancy" had taken over Germany, he hoped that war would be averted if Germany's "democratic forces" could re-assert control of its government.[183] To discourage conflict, he invited Germany to engage in a mutual de-escalation of the two countries naval building projects, but his offer was rebuffed.[184]

As part of his naval reforms, he pushed for higher pay and greater recreational facilities for naval staff,[185] an increase in the building of submarines,[186] and a renewed focus on the Royal Naval Air Service, encouraging them to experiment with how aircraft could be used for military purposes.[187] He coined the term "seaplane" and ordered 100 to be constructed.[188] In 1913 he began taking flying lessons at Eastchurch air station, although close friends urged him to stop given the dangers involved.[189] Some Liberals objected to his levels of naval expenditure; in December 1913 he threatened to resign if his proposal for four new battleships in 1914–15 was rejected.[190] In June 1914, he convinced the House of Commons to authorise the government purchase of a 51 percent share in the profits of oil produced by the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, to secure continued oil access for the Royal Navy.[191] As a supporter of eugenics, he participated in the drafting of the Mental Deficiency Act 1913; however, the Act, in the form eventually passed, rejected his preferred method of sterilisation of the feeble-minded in favour of their confinement in institutions.[192]

—Winston Churchill, introducing the second reading of the Home Rule Bill, April 1912[193]

Taking centre stage was the issue of how Britain's government should respond to the Irish home rule movement.[194] In 1912, Asquith's government forwarded the Home Rule Bill, which if passed into law would grant Irish home rule. Churchill supported the bill and urged Ulster Unionists—a largely Protestant community who desired continued political unity with Britain—to accept it.[195] He opposed partition of Ireland, and in 1913 suggested that Ulster have some autonomy from an independent Irish government.[196] Many Ulster Unionists rejected any option that left them under the jurisdiction of a Dublin-based government and the Ulster Volunteers threatened an uprising to establish an independent Protestant state in Ulster.[197] Churchill was the Cabinet minister tasked with giving an ultimatum to those threatening violence, doing so in a Bradford speech in March 1914.[198] Following a Cabinet decision, he boosted the naval presence in Ireland to deal with any Unionist uprising; Conservatives accused him of trying to initiate an "Ulster Pogrom".[199] Seeking further compromise to calm the Ulster Volunteers, Churchill suggested that Ireland remain part of a federal United Kingdom; this in turn angered Liberals and Irish nationalists.[200]

Outbreak of the First World War

—Winston Churchill to his wife, July 1914[201]

Following the June 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria there was growing talk of war in Europe.[202] Churchill began readying the navy for conflict.[203] Although there was strong opposition within the Liberal Party to involvement in the conflict,[204] the British Cabinet declared war when Germany invaded Belgium.[205] Churchill was tasked with overseeing Britain's naval warfare effort.[206] In two weeks, the navy transported 120,000 British troops across the English Channel to France.[206] In August, he oversaw a naval blockade of German North Sea ports to prevent them from transporting food by sea;[207] he also sent submarines to the Baltic Sea to assist the Russian Navy against German warships.[207] Also in August, he sent the Marine Brigade to Ostend to force the Germans to reallocate some of their troops away from their main southward thrust.[208]

In September, Churchill took over full responsibility for Britain's aerial defence,[208] making several visits to France to oversee the war effort.[209] While in Britain, he spoke at all-party recruiting rallies in London and Liverpool,[210] and his wife gave birth to their third child, Sarah.[211] In October he visited Antwerp to observe Belgian defences against the besieging Germans; he promised Belgian Prime Minister Charles de Broqueville that Britain would provide reinforcements for the city.[212] The German assault continued, and shortly after Churchill left the city he agreed to a British retreat, allowing the Germans to take Antwerp; many in the press criticised Churchill for this.[213] Churchill maintained that his actions prolonged the resistance, thus enabling the Allies to secure Calais and Dunkirk.[214]

In November, Asquith called a War Council, consisting of himself, Lloyd George, Edward Grey, Kitchener, and Churchill.[215] Churchill proposed a plan to seize the island of Borkum and use it as a post from which to attack Germany's northern coastline, believing that this strategy should shorten the war.[216] Churchill also encouraged the development of the tank, which he believed would be useful in overcoming the problems of trench warfare, and financed its creation with admiralty funds.[217] To relieve Turkish pressure on the Russians in the Caucasus, Churchill was part of a plan to distract the Turkish Army by attacking in the Dardanelles, with the hope that if successful the British could seize Constantinople.[218] In March, a fleet of 13 battleships attacked in the Dardanelles but faced severe problems from submerged mines; in April, the 29th Division began its assault at Gallipoli.[219] Many MPs, particularly Conservatives, blamed Churchill for the failure of these campaigns.[220] Amid growing Conservative pressure, in May, Asquith agreed to form an all-party coalition government; the Conservatives' one condition of entry was that Churchill be demoted from his position at the Admiralty.[221] Churchill pleaded his case with both Asquith and Conservative leader Bonar Law, but ultimately accepted his demotion to the position of Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster.[222]

Military service, 1915–1916

In November 1915, Churchill resigned from the government, although he remained an MP; Asquith rejected his request to be appointed Governor-General of British East Africa.[223] Moving into his brother's home in South Kensington, he and his family spent weekends at a Tudor farmhouse near Godalming, where he took up painting, which became a lifelong hobby.[224]

In November Churchill joined the 2nd Battalion, Grenadier Guards, on the Western Front.[225] After a brief trip back to London for Christmas,[226] in January 1916 he was promoted to lieutenant-colonel and placed in command of the 6th Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers.[227] After a period of training, the Battalion was moved to a sector of the Front near Ploegsteert in Belgium.[228] Churchill spent three and a half months at the Front; his Battalion faced continual shelling although no German offensive.[229] In March he returned home briefly, making a speech on naval issues to the House of Commons.[230] In May, the 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers were merged into the 15th Division. Churchill did not request a new command, instead securing permission to leave active service.[231]

Back in the House of Commons, Churchill spoke out on war issues, calling for conscription to be extended to the Irish, greater recognition of soldiers' bravery, and for the introduction of steel helmets for troops.[232] He nevertheless was frustrated that there was little for him to do.[233] The failure of the Dardanelles hung over him, with the issue repeatedly being raised by the Conservatives and pro-Conservative press.[234] He argued his case before the Dardanelles Commission, whose published report placed no blame on him for the campaign's failure.[235]

Lloyd George government: 1916–1922

Minister of Munitions: 1917–1919

Asquith resigned and Lloyd George became Prime Minister in October 1916; in May 1917, the latter sent Churchill to inspect the French war effort.[236] In July, Lloyd George appointed Churchill Minister of Munitions.[237] In this position, Churchill made a commitment to increase munitions production, streamlined the organisation of the department, and soon negotiated an end to a strike in munitions factories along the Clyde.[238] He ended a second strike, in June 1918, by threatening to conscript strikers into the army.[239] He made repeated trips to France, visiting the Front and meeting with French political leaders, including its Prime Minister, Georges Clemenceau.[240] In the House of Commons, he voted in support of the Representation of the People Act 1918, which first gave some British women the right to vote.[241] Following British military gains, in November, Germany surrendered.[242] Four days later, Churchill's fourth child, Marigold, was born.[243]

Secretary of State for War and Air: 1919–1921

After the war, Lloyd George called a new election.[244] During the election campaign, Churchill called for the nationalisation of the railways, a control on monopolies, tax reform, and the creation of a League of Nations to prevent future wars.[245] In the election, Churchill was returned as MP for Dundee and Lloyd George retained as Prime Minister.[245] In January 1919, Lloyd George then moved Churchill to the War Office as both Secretary of State for War and Secretary of State for Air.[246]

Churchill was responsible for demobilising the British Army,[247] although he convinced Lloyd George to keep a million men conscripted to use as a British Army of the Rhine.[248] Churchill was one of the few government figures who opposed harsh measures against the defeated Germany.[243] He stated that he opposed any punitive measures that would reduce "the mass of the working-class population of Germany to a condition of sweated labour and servitude".[245] He also cautioned against demobilising the German Army, warning that they may be needed as a bulwark against threats from the newly established Soviet Russia.[249]

Churchill was an outspoken opponent of Vladimir Lenin's new Communist Party government in Russia,[250] stating that "of all the tyrannies in history, the Bolshevik tyranny is the worst".[251] British troops were already in parts of the former Russian Empire, assisting the anti-Communist White forces amid the ongoing Russian Civil War.[252] Although initially committed to British involvement,[253] Churchill concluded there was insufficient British desire for another war, and convinced Lloyd George to bring the British troops home, albeit continuing to provide the Whites with arms and supplies.[254] In his words, "if Russia is to be saved [from the Communists], as I pray she may be saved, she must be saved by Russians", not by foreign troops.[255] He took responsibility for evacuating the 14,000 British troops from Russia.[256] After the Soviets won the civil war, Churchill proposed a cordon sanitaire around the country.[257]

Churchill's attentions were also turned to the Irish War of Independence, where he supported the use of the para-military Black and Tans to combat Irish revolutionaries.[258] After British troops in Iraq clashed with Kurdish rebels, Churchill authorised two squadrons to the area, proposing that they be equipped with mustard gas to use against the rebels.[259] More broadly, he saw the occupation of Iraq as a drain on Britain and proposed, unsuccessfully, that the government should hand control of central and northern Iraq back to Turkey.[260]

Secretary of State for the Colonies: 1921–1922

Churchill became Secretary of State for the Colonies in February 1921.[261] The following month, the first exhibit of his paintings was held; it took place in Paris, with Churchill exhibiting under a pseudonym.[261] In May, his mother died, followed in August by his daughter Marigold.[262] A key issue that year was the ongoing Irish War of Independence. To end it, Churchill pushed for a truce, which came into effect in July.[263] In October, he was among the seven British negotiators who met Sinn Féin leaders in Downing Street.[264] He suggested Ireland be given home rule within the Empire but with the six Protestant-majority counties of Ulster having some autonomy from a Dublin government: the Ulster Unionists rejected this.[264] It was then agreed that Ireland would be partitioned; most of the country would form the Irish Free State, while the Protestant-majority areas would form Northern Ireland and remain part of the UK. This was written into the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which Churchill helped draft.[264] After the treaty, Churchill successfully called for Sinn Féin members who were guilty of murder to have their death penalties waived.[264] As Ireland descended into civil war between supporters and republican opponents of the treaty, Churchill supplied weapons to the forces of Michael Collins' pro-treaty government.[265]

Churchill was responsible for reducing the cost of occupying the Middle East.[261] He urged removing most British troops from Iraq and installing an Arab government.[261] In March he met British officials responsible for governing Iraq in Cairo. They agreed to install Faisal as King of Iraq and his brother, Abdullah, as King of Transjordan.[266] From there he travelled to Mandatory Palestine, where Arab Palestinians petitioned him not to allow further Jewish migration.[267] A supporter of Zionism, he dismissed this.[268] Churchill believed that he could encourage Jewish migration to Palestine while allaying Arab fears that they would become a dominated minority.[269] Only following the 1921 Jaffa riots did he agree to temporary restrictions on Jewish migration to Palestine.[270] With Turkey seeking to expand into areas lost during the First World War, Churchill backed Lloyd George in holding British control of Constantinople. Turkish troops advanced towards the British, leading to the Chanak Crisis, with Churchill calling on British troops to stay firm.[271]

In late 1921 Lloyd George made Churchill chair of a Cabinet Committee on Defence Estimates, which met in January 1922 to determine how much military expenditure could be cut without jeopardising national security.[272] In December 1921 he holidayed in the south of France, where he began writing a book about his experiences during the First World War.[273] In September 1922 his fifth child, Mary, was born, and that month he purchased a new house, Chartwell, in Kent.[274] In October 1922 Churchill underwent an operation for appendicitis. While this was occurring, the Conservatives withdrew from Lloyd George's coalition government, precipitating the November 1922 general election,[275] in which Churchill lost his Dundee seat to prohibitionist Edwin Scrymgeour, coming fourth in terms of vote share.[276]

Out of Parliament: 1922–1924

Churchill spent the next six months largely at the Villa Rêve d'Or near Cannes, where he devoted himself to painting and writing his memoirs.[277] He produced a five-volume series of books about the war, its build-up, and its aftermath, titled The World Crisis; the first volume appeared in April 1923 and the others over the course of ten years.[278] After a 1923 general election election was called, seven Liberal associations asked Churchill to stand as their candidate, and he selected that at Leicester West. He did not win the seat.[279] A Labour government led by Ramsay MacDonald took power, although Churchill had hoped they would be kept out of office by a coalition of the Conservatives and Liberals.[280] He strongly opposed the MacDonald government's decision to loan money to Soviet Russia and feared the signing of an Anglo-Soviet Treaty.[281]

In 1924, Churchill stood as an independent candidate in the Westminster Abbey by-election but was defeated.[282] In May he then addressed a Conservative meeting in Liverpool—the first time he had spoken to a Conservative group for twenty years—in which he declared that there was no longer a place for the Liberal Party in British politics and that Liberals must therefore back the Conservatives to stop Labour and ensure "the successful defeat of Socialism".[283] In July, he agreed with Conservative leader Stanley Baldwin that he would be selected as the Conservative candidate for a seat—in September he was chosen for Epping—but that he did not have to stand under the Conservative banner, instead describing himself as a "Constitutionalist".[284] The general election occurred in October, with Churchill winning in Epping.[285] The Conservatives were victorious, with Baldwin forming the new government. Although Churchill had no background in finance or economics, Baldwin appointed him as Chancellor of the Exchequer.[286]

Chancellor of the Exchequer: 1924–1929

Becoming Chancellor of the Exchequer on 6 November 1924, Churchill moved into 11 Downing Street and formally rejoined the Conservative Party.[287] He intended to pursue "the same sort of measures" as under the Liberal social reforms.[287] In January 1925, he negotiated a series of war repayments, both from the UK to the US, and from other countries to the UK.[288] The Bank of England and others were calling for the UK to return to the gold standard, an idea Churchill initially opposed. He consulted various economists, the majority of whom endorsed the change; among the few who opposed it was John Maynard Keynes. Churchill ultimately relented and agreed to the measure, after which he became its supporter.[289]

In April 1925, he announced the return to the gold standard in his first budget which included measures to reduce the pension age from 70 to 65; for widows to begin receiving their pension as soon as their husband died; and a ten percent decrease in income tax for the lowest earners which he hoped would stimulate small businesses.[290] As a counter-measure, Churchill called for a reduction in naval expenditure, arguing that it was not needed in peacetime.[291] Later, he convinced the government to introduce a subsidy for the mining industry to prevent reduction of wages in response to lower income.[292] His second budget, announced in April 1926, included taxes on petrol, heavy lorries and luxury car purchase.[293]

During the General Strike of 1926, Churchill edited the British Gazette, the government's anti-strike propaganda newspaper.[294] After the strike ended, he acted as an intermediary between the striking miners and the mine owners. He proposed that any lowering of wages should be paralleled by a reduction in the owners' profits but no compromise could be reached and Churchill became an advocate of the miners' calls for the introduction of a legally binding minimum wage.[295]

In early 1927, Churchill travelled through Europe, visiting Malta, Athens, Rome, and Paris.[296] In Athens, he praised the restoration of parliamentary democracy; in Rome, he met Mussolini whom he praised for his stand against Leninism.[297] In April, Churchill announced his third budget including new taxes on imported car tyres and wines, and increased taxation on matches and tobacco.[298] Later, he proposed abolition of local rates to relieve taxation on British industry and agriculture; eventually, after Cabinet criticism, he agreed to a two-thirds reduction and the scheme was included in his April 1928 budget.[299] In April 1929, he presented his fifth and final budget including abolition of duty on tea.[300]

The "Wilderness Years": 1929–1939

Marlborough and the India Question: 1929–1932

In the 1929 general election, Churchill retained his Epping seat but the Conservatives were defeated and MacDonald formed his second Labour government.[301] Out of office, Churchill began work on Marlborough: His Life and Times, a four-volume biography of his ancestor John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough.[302] Hoping that the Labour government could be ousted, he gained Baldwin's approval to work towards establishing a Conservative-Liberal coalition, although many Liberals were reticent.[302] In August he travelled to Canada with his brother and son, giving speeches in Ottawa and Toronto, before travelling through the United States.[303] In San Francisco he met with William Randolph Hearst, who convinced Churchill to write for his newspapers;[304] in Hollywood he dined with the film star Charlie Chaplin.[305] From there he travelled through the Mojave Desert to the Grand Canyon and then to Chicago and finally New York City.[305]

Back in London, Churchill was angered by the Labour government's decision—backed by the Conservative Shadow Cabinet—to grant Dominion status to India.[306] He argued that giving India enhanced levels of home rule would hasten calls for full independence from the British Empire.[307] In December 1930 he was the main speaker at the first public meeting of the Indian Empire Society, set up to oppose the granting of Dominion status.[308] In his view, India was not ready for home rule. He believed that the Hindu Brahmin caste would gain control and further oppress both the "untouchables" and the religious minorities.[309] When riots between Hindus and Muslims broke out in Cawnpore in March 1931, he cited it in support of his argument.[310]

Churchill called for swift action against any Indian independence activists engaged in illegal activity.[308] He wanted the Indian National Congress party to be disbanded and its leaders deported.[311] In 1930, he stated that "Gandhi-ism and everything it stands for will have to be grappled with and crushed".[312] He thought it "alarming and nauseating" that the Viceroy of India agreed to meet with independence activist Mohandas Gandhi, whom Churchill considered "a seditious Middle Temple lawyer, now posing as a fakir".[313] These views enraged Labour and Liberal opinion although were supported by many grassroot Conservatives.[314] Angered that Baldwin was supporting the reform, Churchill resigned from the Shadow Cabinet.[315]

In October 1930, Churchill published his autobiography, My Early Life, which sold well and was translated into multiple languages.[316] The October 1931 general election was a landslide victory for the Conservatives[317] Churchill nearly doubled his majority in Epping, but he was not given a ministerial position.[318] The following month saw the publication of The Eastern Front, the final volume of The World Crisis.[319] The Commons debated Dominion Status for India on 3 December and Churchill insisted on dividing the House. This backfired as only 43 MPs supported him and 369 voted for the government.[319]

At this time, however, Churchill's main interest was in recovering financial losses (about £12,000) he had sustained in the Wall Street Crash and he embarked on a potentially lucrative lecture tour of North America, accompanied by Clementine and Diana. They arrived in New York City on 11 December and Churchill gave his first lecture in Worcester, Massachusetts the following night.[317][319] On 13 December, he was back in New York and travelled by cab to meet his friend Bernard Baruch. Having left the cab, he was crossing Fifth Avenue when he was knocked down by a car that was exceeding the speed limit. He suffered a head wound, two cracked ribs and general bruising from which he developed neuritis. He was hospitalised for eight days and then began a period of convalescence at his hotel until New Year's Eve.[320] While he was there he sent an article about his experience to the Daily Mail and afterwards received thousands of letters and telegrams from well-wishers.[321] To further his convalescence, he and Clementine took ship to Nassau for three weeks but Churchill became depressed there, not just about the accident but also about his financial and political losses.[322] Meanwhile, the lecture agency managed to reschedule many of his engagements and, on returning to America in late January, he was able to fulfil nineteen of them until 11 March, though he remained mostly in the north-east and did not go further west than Chicago.[323] He arrived back home on 18 March.[322]

Having worked on Marlborough for much of 1932, Churchill in late August decided to visit the battlefields of "John Duke" (Churchill's pet name for him) in Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany. He travelled with Lindemann.[324] In Munich, he met Ernst Hanfstaengl, a friend of Hitler, who was then rising in prominence. Talking to Hanfstaengl, Churchill raised concerns about Hitler's anti-Semitism and, probably because of that, missed the opportunity to meet his future enemy.[325] Churchill went from Munich to Blenheim. Soon afterwards, he was afflicted with paratyphoid fever. He was taken over the border into Austria and spent two weeks at a sanatorium in Salzburg.[326] He returned to Chartwell on 25 September, still working on Marlborough. Two days later, he collapsed while walking in the grounds after a recurrence of paratyphoid which caused an ulcer to haemorrhage. He was taken to a London nursing home and remained there until late October, missing the Conservative Party Conference.[327]

While Churchill was in Salzburg, the German Chancellor Franz von Papen requested that the other Western powers accept Germany's right to re-arm, something they had been forbidden from doing by the Treaty of Versailles. Foreign Secretary John Simon, rejected the request and affirmed that Germany was still bound by the treaty's disarmament clauses. Churchill later supported Simon as he believed that a re-armed Germany would soon pursue the re-conquest of territories lost in the previous conflict.[328]

Warnings about Germany and the abdication crisis: 1933–1936

After Hitler came to power on 30 January 1933, Churchill was quick to recognise the menace to civilisation of such a regime. As early as 13 April that year, he addressed the Commons on the matter, speaking of "odious conditions in Germany" and the threat of "another persecution and pogrom of Jews" being extended to other countries, including Poland.[329][330] On the issue of militarism, Churchill expressed alarm that the British government had reduced air force spending and warned that Germany would soon overtake Britain in air force production.[331][332]

Between October 1933 and September 1938, the four volumes of Churchill's Marlborough: His Life and Times were published.[333] In November 1934, he gave a radio broadcast in which he warned of Nazi intentions and called on Britain to prepare itself for conflict. This was the first time that his concerns about German militarism were heard by such a large audience.[334] In December, the India Bill entered parliament and was passed in February 1935. Churchill and 83 other Conservative MPs voted against it.[335] He continued to express misgivings but did message Gandhi, saying: "You have got the thing now; make it a success and if you do I will advocate your getting much more".[336] In June 1935, MacDonald resigned and was replaced as prime minister by Baldwin.[337] Baldwin then led the Conservatives to victory in the 1935 general election; Churchill retained his seat with an increased majority but was again left out of the government.[338]

Armed with official data provided clandestinely by two senior civil servants, Desmond Morton and Ralph Wigram, Churchill was able to speak with authority about what was happening in Germany, especially the development of the Luftwaffe.[339] He had some involvement with a group called the Anti-Nazi Council, despite its being primarily leftist in political outlook, and called for improved training of troops and airmen. He also warned that industry must prepare for wartime production.[340]

In January 1936, Edward VIII succeeded his father, George V, as monarch. Churchill liked Edward but disapproved of his desire to marry an American divorcee, Wallis Simpson.[341] Marrying Simpson would necessitate Edward's abdication and a constitutional crisis developed.[342] Churchill was opposed to abdication and, in the House of Commons, he and Baldwin clashed on the issue.[343] Afterwards, although Churchill immediately pledged loyalty to George VI, he wrote that the abdication was "premature and probably quite unnecessary".[344]

Anti-appeasement: 1937–1939

In May 1937, Baldwin resigned and was succeeded as prime minister by Neville Chamberlain. At first, Churchill welcomed Chamberlain's appointment but, in February 1938, matters came to a head after Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden resigned over Chamberlain's appeasement of Mussolini,[345] a policy which Chamberlain was extending towards Hitler.[346]

Meanwhile, Churchill had continued writing fortnightly articles for the Evening Standard, and these were reprinted in various newspapers across Europe through the efforts of Emery Reves' Paris-based press service.[347] In September 1937, Churchill wrote an Evening Standard piece in which he directly appealed to Hitler, asking the latter to cease his persecution of Jews and religious organisations.[348] The following month, a selection of his articles were published in a collected volume called Great Contemporaries.[349]

In 1938, Churchill warned the government against appeasement and called for collective action to deter German aggression. In March, the Evening Standard ceased publication of his fortnightly articles, but the Daily Telegraph published them instead.[350][351] Following the German annexation of Austria, Churchill spoke in the House of Commons, declaring that "the gravity of the events[…] cannot be exaggerated".[352] He began calling for a mutual defence pact among European states threatened by German expansionism, arguing that this was the only way to halt Hitler.[353] This was to no avail as, in September, Germany mobilised to invade the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia.[354] Churchill visited Chamberlain at Downing Street and urged him to tell Germany that Britain would declare war if the Germans invaded Czechoslovak territory; Chamberlain was not willing to do this.[355] On 30 September, Chamberlain signed up to the Munich Agreement, agreeing to allow German annexation of the Sudetenland. Speaking in the House of Commons on 5 October, Churchill called the agreement "a total and unmitigated defeat".[356][357][358]

First Lord of the Admiralty: September 1939 to May 1940

The Phoney War and the Norwegian Campaign

On 3 September 1939, the day Britain declared war on Germany following the outbreak of the Second World War, Chamberlain appointed Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty, the same position he had held at the beginning of the First World War. As such he was a member of Chamberlain's war cabinet. Churchill later claimed that, on learning of his appointment, the Board of the Admiralty sent a signal to the Fleet: "Winston is back".[359] Although this story was repeated by Lord Mountbatten in a speech at Edmonton in 1966, Richard Langworth notes that neither he nor Churchill's official biographer Martin Gilbert have found contemporary evidence to confirm it, suggesting that it may well be a later invention.[360]

As First Lord, Churchill proved to be one of the highest-profile ministers during the so-called "Phoney War", when the only significant action by British forces was at sea. Churchill was ebullient after the Battle of the River Plate on 13 December 1939 and afterwards welcomed home the crews, congratulating them on "a brilliant sea fight" and saying that their actions in a cold, dark winter had "warmed the cockles of the British heart".[361] On 16 February 1940, Churchill personally ordered Captain Philip Vian of the destroyer HMS Cossack to board the German supply ship Altmark in Norwegian waters and liberate some 300 British prisoners who had been captured by the Admiral Graf Spee. These actions, supplemented by his speeches, considerably enhanced Churchill's reputation.[361]

He was concerned about German naval activity in the Baltic Sea and initially wanted to send a naval force there but this was soon changed to a plan, codenamed Operation Wilfred, to mine Norwegian waters and stop iron ore shipments from Narvik to Germany.[362] There were disagreements about mining, both in the war cabinet and with the French government. As a result, Wilfred was delayed until 8 April 1940, the day before the German invasion of Norway was launched.[363]

The Norway Debate and Chamberlain's resignation

After the Allies failed to prevent the German occupation of Norway, the Commons held an open debate from 7 to 9 May on the government's conduct of the war. This has come to be known as the Norway Debate and is renowned as one of the most significant events in parliamentary history.[364] On the second day (Wednesday, 8 May), the Labour opposition called for a division which was in effect a vote of no confidence in Chamberlain's government.[365] There was considerable support for Churchill on both sides of the House but, as a member of the government, he was obliged to speak on its behalf. He was called upon to wind up the debate, which placed him in the difficult position of having to defend the government without damaging his own prestige.[366] Although the government won the vote, its majority was drastically reduced amid calls for a national government to be formed.[367]

In the early hours of 10 May, German forces invaded Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands as a prelude to their assault on France.[368] Since the division vote, Chamberlain had been trying to form a coalition but Labour declared on the Friday afternoon that they would not serve under his leadership, although they would accept another Conservative. The only two candidates were Churchill and Lord Halifax, the Foreign Secretary. The matter had already been discussed at a meeting on the 9th between Chamberlain, Halifax, Churchill, and David Margesson, the government Chief Whip.[368] Halifax admitted that he could not govern effectively as a member of the House of Lords and so Chamberlain advised the King to send for Churchill, who became prime minister.[369] His first act was to write to Chamberlain and thank him for his support.[370]

Churchill later wrote of feeling a profound sense of relief in that he now had authority over the whole scene. He believed himself to be walking with destiny and that his life so far had been "a preparation for this hour and for this trial".[371][372][373]

Prime Minister: 1940–1945

Dunkirk to Pearl Harbor: May 1940 to December 1941

Initial reaction to Churchill as Premier

In May, Churchill was still unpopular with many Conservatives, with probably the majority of the Labour Party, and with the so-called Establishment – Jenkins says his accession to the premiership was "at best the equivalent of an abrupt wartime marriage".[374] He probably could not have won a majority in any of the political parties in the House of Commons, and the House of Lords was completely silent when it learned of his appointment.[375][376] Chamberlain remained Conservative Party leader until October when ill health forced his resignation – he died of cancer in November. By that time, Churchill had won the doubters over and his succession as party leader was a formality.[377] Ralph Ingersoll reported in November: "Everywhere I went in London people admired [Churchill's] energy, his courage, his singleness of purpose. People said they didn't know what Britain would do without him. He was obviously respected. But no one felt he would be Prime Minister after the war. He was simply the right man in the right job at the right time. The time being the time of a desperate war with Britain's enemies".[378]

War ministry created

Churchill began his premiership by forming a five-man war cabinet which included Chamberlain as Lord President of the Council, Labour leader Clement Attlee as Lord Privy Seal (later as Deputy Prime Minister), Halifax as Foreign Secretary and Labour's Arthur Greenwood as a minister without portfolio. In practice, these five were augmented by the service chiefs and ministers who attended the majority of meetings.[379][380] The cabinet changed in size and membership as the war progressed. By the end of 1940, it had increased to eight after Churchill, Attlee and Greenwood were joined by Ernest Bevin as Minister of Labour and National Service; Anthony Eden as Foreign Secretary – replacing Halifax, who was sent to Washington D.C. as ambassador to the United States; Lord Beaverbrook as Minister of Aircraft Production; Sir Kingsley Wood as Chancellor of the Exchequer; and Sir John Anderson as Lord President of the Council – replacing Chamberlain who died in November (Anderson later became Chancellor after Kingsley Wood's death in September 1943). Jenkins described this combination as a "war cabinet for winning", contrasting it with Chamberlain's "war cabinet for losing".[381] In response to previous criticisms that there had been no clear single minister in charge of the prosecution of the war, Churchill created and took the additional position of Minister of Defence, making him the most powerful wartime prime minister in British history.[375]

Churchill wanted people he knew and trusted to take part in government. Among these were personal friends like Beaverbrook and Frederick Lindemann, who became the government's scientific advisor.[382] Lindemann was one of several outside experts drafted in and these "technocrats" fulfilled vital functions, especially on the Home Front.[382] Churchill would proudly proclaim that his government, in the interests of national unity, was the most broadly based in British political history as it spanned far right to far left by including such figures as Lord Lloyd on the right and Ellen Wilkinson on the left.[382]

Resolve to fight on

At the end of May, with the British Expeditionary Force in retreat to Dunkirk and the Fall of France seemingly imminent, Halifax proposed that the government should explore the possibility of a negotiated peace settlement using Mussolini as an intermediary given that Italy was still neutral. There were several high-level meetings from 26 to 28 May, including two with the French premier Paul Reynaud.[383] Churchill's resolve was to fight on, even if France capitulated, but his position remained precarious until Chamberlain resolved to support him. Churchill had the full support of the two Labour members but knew he could not survive as prime minister if both Chamberlain and Halifax were against him. In the end, by gaining the support of his outer cabinet, Churchill outmanoeuvred Halifax and won Chamberlain over.[384] The essence of Churchill's argument was that, as he said, "it was idle to think that, if we tried to make peace now, we should get better terms than if we fought it out".[385] He therefore concluded that the only option was to fight on though, at times, he personally was pessimistic about the chances of a British victory, as on 12 June 1940 when he told General Hastings Ismay that "[y]ou and I will be dead in three months' time".[377] Nonetheless, his use of rhetoric hardened public opinion against a peaceful resolution and prepared the British people for a long war – Jenkins says Churchill's speeches were "an inspiration for the nation, and a catharsis for Churchill himself".[386]

Importance of Churchill's wartime speeches

As Jenkins said, Churchill's wartime speeches were a great inspiration to the embattled British, beginning with his first as prime minister, which he had delivered to the Commons on 13 May: the "blood, toil, tears and sweat" speech. It was not well-received at the time, mainly because the majority of Conservative MPs held doubts about Churchill's suitability to be premier. It was in fact little more than a short statement but, Jenkins says, "it included phrases which have reverberated down the decades".[387] Churchill made it plain to the nation that a long, hard road lay ahead and that victory was the final goal:[388][389]

I would say to the House, as I said to those who have joined this government, that I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat. We have before us an ordeal of the most grievous kind. We have before us many, many long months of struggle and of suffering. You ask, what is our policy? I will say: it is to wage war, by sea, land and air, with all our might and with all the strength that God can give us; to wage war against a monstrous tyranny, never surpassed in the dark, lamentable catalogue of human crime. That is our policy. You ask, what is our aim? I can answer in one word: it is victory, victory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror, victory, however long and hard the road may be; for without victory, there is no survival. Let that be realised; no survival for the British Empire, no survival for all that the British Empire has stood for, no survival for the urge and impulse of the ages, that mankind will move forward towards its goal. But I take up my task with buoyancy and hope. I feel sure that our cause will not be suffered to fail among men. At this time I feel entitled to claim the aid of all, and I say: Come then, let us go forward together with our united strength.

Operation Dynamo and the Battle of France

Operation Dynamo, the evacuation of 338,226 Allied servicemen from Dunkirk, ended on Tuesday, 4 June when the French rearguard surrendered. The total was far in excess of expectations and it gave rise to a popular view that Dunkirk had been a miracle, and even a victory.[390] Churchill himself referred to "a miracle of deliverance" in his "we shall fight on the beaches" speech to the Commons that afternoon, though he shortly reminded everyone that: "We must be very careful not to assign to this deliverance the attributes of a victory. Wars are not won by evacuations". The speech ended on a note of defiance coupled with a clear appeal to the United States:[391][392]

We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air. We shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills. We shall never surrender, and even if, which I do not for a moment believe, this Island or a large part of it were subjugated and starving, then our Empire beyond the seas, armed and guarded by the British Fleet, would carry on the struggle, until, in God's good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the old.

Germany initiated Fall Rot the following day and Italy entered the war on the 10th.[393] The Wehrmacht occupied Paris on the 14th and completed their conquest of France on 25 June.[394] It was now inevitable that Hitler would attack and probably try to invade Great Britain. Faced with this, Churchill addressed the Commons on 18 June and delivered one of his most famous speeches, ending with this peroration:[395][396][397]

What General Weygand called the "Battle of France" is over. I expect that the Battle of Britain is about to begin. Upon this battle depends the survival of Christian civilisation. Upon it depends our own British life and the long continuity of our institutions and our Empire. The whole fury and might of the enemy must very soon be turned on us. Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him all Europe may be free, and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands; but if we fail then the whole world, including the United States, and all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new dark age made more sinister, and perhaps more prolonged, by the lights of a perverted science. Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duty and so bear ourselves that if the British Commonwealth and Empire lasts for a thousand years, men will still say: "This was their finest hour".

Churchill was determined to fight back and ordered the commencement of the Western Desert campaign on 11 June, an immediate response to the Italian declaration of war. This went well at first while the Italian army was the sole opposition and Operation Compass was a noted success. In early 1941, however, Mussolini requested German support and Hitler sent the Afrika Korps to Tripoli under the command of Generalleutnant Erwin Rommel, who arrived not long after Churchill had halted Compass so that he could reassign forces to Greece where the Balkans campaign was entering a critical phase.[398]