Natural disasters in India

Natural disasters in India, many of them related to the climate of India, cause massive losses of life and property. Droughts, flash floods, cyclones, avalanches, landslides brought by torrential rains, and snowstorms pose the greatest threats. A natural disaster might be caused by earthquakes, flooding, volcanic eruption, landslides, hurricanes etc. In order to be classified as a disaster it will have profound environmental effect and/or human loss and frequently incurs financial loss.[1] Other dangers include frequent summer dust storms, which usually track from north to south; they cause extensive property damage in North India[2] and deposit large amounts of dust from arid regions. Hail is also common in parts of India, causing severe damage to standing crops such as rice and wheat and many more crops.

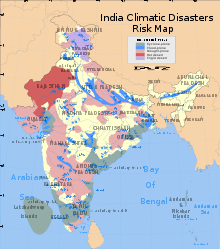

Disaster-prone regions in India. |

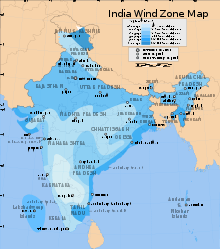

Map showing winds zones, shaded by distribution of average speeds of prevailing winds. |

Landslides and Avalanches Landslides are very common in the Lower Himalayas. The young age of the region's hills result in rock formations, which are susceptible to slippages. Rising population and development pressures, particularly from logging and tourism, cause deforestation. The result is denuded hillsides which exacerbate the severity of landslides; since tree cover impedes the downhill flow of water.[3] Parts of the Western Ghats also suffer from low-intensity landslides. Avalanches occurrences are common in Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Sikkim etc. Landslides in India are also highly dangerous as many Indian families and farmers preside in the hills or mountains. Also, the monsoon season in India is very severe. These cause a lot of loss to life and property.

Floods in India

Floods are the most common natural disaster in India. The heavy southwest monsoon rains cause the Brahmaputra and other rivers to distend their banks, often flooding surrounding areas. Though they provide rice paddy farmers with a largely dependable source of natural irrigation and fertilisation, the floods can kill thousands and displace millions. Excess, erratic, or untimely monsoon rainfall may also wash away or otherwise ruin crops.[4][5] Almost all of India is flood-prone, and extreme precipitation events, such as flash floods and torrential rains, have become increasingly common in central India over the past several decades, coinciding with rising temperatures. Meanwhile, the annual precipitation totals have shown a gradual decline, due to a weakening monsoon circulation[6] as a result of the rapid warming in the Indian Ocean[7] and a reduced land-sea temperature difference. This means that there are more extreme rainfall events intermittent with longer dry spells over central India in the recent decades.

Cyclones in India

Intertropical Convergence Zone, may affect thousands of Indians living in the coastal regions. Tropical cyclogenesis is particularly common in the northern reaches of the Indian Ocean in and around the Bay of Bengal. Cyclones bring with them heavy rains, storm surges, and winds that often cut affected areas off from relief and supplies. In the North Indian Ocean Basin, the cyclone season runs from April to December, with peak activity between May and November.[8] Each year, an average of eight storms with sustained wind speeds greater than 63 kilometres per hour (39 mph) form; of these, two strengthen into true tropical cyclones, which have sustained gusts greater than 117 kilometres per hour (73 mph). On average, a major (Category 3 or higher) cyclone develops every other year.[8][9]

During summer, the Bay of Bengal is subject to intense heating, giving rise to humid and unstable air masses that produce cyclones. Many powerful cyclones, including the 1737 Calcutta cyclone, the 1970 Bhola cyclone, the 1991 Bangladesh cyclone and the 1999 Odisha cyclone and the most latest cyclone fani in Odisha and cyclone vayu in gujrat have led to widespread devastation along parts of the eastern coast of India and neighboring Bangladesh. Widespread death and property destruction are reported every year in exposed Tamil Nadu, and West Bengal. India's western coast, bordering the more placid Arabian Sea, experiences cyclones only rarely; these mainly strike Gujarat and, less frequently, Kerala and sometimes Odisha.

In terms of damages and loss of life, Cyclone 05B, a Super Cyclone that struck Odisha on 29 October 1999, was the worst in more than a quarter-century. With peak winds of 160 miles per hour (257 km/h), it was the equivalent of a Category 5 hurricane.[10] Almost two million people were left homeless;[11] another 20 million people's lives were disrupted by the cyclone.[11] Officially, 9,803 people died from the storm;[10] unofficial estimates place the death toll at over 10,100.[11]

In terms of damages and assets destruction, 2020 Cyclone Amphan ;[12] a Super Cyclone that struck West Bengal, Odisha & Bangladesh on 20 May 2020, is currently the worst in India in the 21st century. With peak winds of 260 kilometres per hour (162 mph) to 280 kilometres per hour (174 mph), it was the equivalent of a Category 5 hurricane.[10] Almost 5 million or 50 lakh people are left homeless in West Bengal, Odisha & Bangladesh ;[12] another 10 million or 1 crore people's lives were disrupted by the cyclone.Officially, 128 people died from the storm. Official Damages & Asset Destruction estimates is 13.40 to 13.69 billion US Dollars ;[13] it is the costliest damage making cyclone ever to occur in Bay of Bengal. The Sunderbans Region of West Bengal & Bangladesh are badly & extensively damaged by this storm.

Climate change impacts on environment

Monsoon

The Indian meteorological department has declared that water cycle will be more intense, with higher annual average rainfall as well increased drought in future years.[14] A 20% rise in monsoon over most states is also predicted.[15] A 2 °C rise in global average temperature will make Indian monsoon highly unpredictable.[16] At 4 °C an extremely wet monsoon which currently has a 1 in 100 year's chance will occur in every 10 years by 2100. Extremes in maximum and minimum temperatures and precipitation will increase particularly over western coast and central and north-east India.[17] The dry years are expected to be drier and wet years wetter due to Climate Change.

Rivers and glaciers

The per capita availability of freshwater in India is expected to drop below 1000 cubic meters by 2025 because of population growth and climate change. River basins of Cauvery, Penna, Mahi, Sabarmati, Tapi, Luni and few others are already water scarce. Krishna and Subarnarekha may become so by 2025. High population density, coastal flooding and saltwater intrusion and exposure to storm surges makes Ganga, Godavari, Krishna and Mahanadi coastal river deltas "hotspots" of climate change vulnerability.[14]

Glaciers are the main source of water for the Himalayan Rivers such as Ganga, Brahmaputra and Indus. 67% of Himalayan glaciers have receded in the past decade and continue to diminish with increasing rates. The Ganga and the Indus are likely to become water scarce by 2025.[18]

Since 1962, the overall glacier area has reduced by 21% from 2077 km2 to 1628 km2. This will lead to water shortages becoming acuter with time and may endanger food security and energy generation.[19]

Sea level rise

Rise in sea temperature and sea level leads to loss of marine ecosystems and biodiversity, salination, erosion and flooding and also increases occurrence and intensity of storms along entire shoreline. Climate Change impacts are already observed in submergence of coastal lands in the Sundarbans,[20] loss of wetlands[21] and of coral reefs by bleaching,[22] and an estimated sea level rise of 1.06 - 1.75 mm/year. Low end scenarios estimate sea levels in Asia will be at least 40 cm higher by 2100. The IPCC calculates that it would expose 13–94 million people to flooding, with about 60% of this total in South Asia. A sea level rise of 100 cm would inundate 5,763 cubic km of India's landmass.[23] It will severely affect populations in megacities like Mumbai, Kolkata and Chennai due to land submergence and extreme weather events.[24] Increase in sea surface temperature increases frequency, intensity, scale and destructive power of tropical cyclones.[25]

Droughts, heat waves and sand storms

500Mha land in the Asia Pacific region is already experiencing land degradation.[26] The summers have already become more intense in India with some regions regularly reporting temperatures around 47 °C.[27] In the last four years, India has seen as many as over 4,620 deaths caused by heat waves, according to data published by the Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India.[28] Indian Meteorological Department declared that the storm that hit northern India in May 2018 was severe and their frequency could increase due to global warming. This is due to increase in the intensity of the wind and dryness of the soil which increases the intensity of dust storms. The rise in land surface temperature will be more pronounced in the northern part of India. A recent study reports that summers could last up to 8 months in the Gangetic plain by 2070 if the global temperature increases beyond 2 °C.[29] Increasingly severe and frequent Heat waves may substantially increase mortality and death incidences.[30] Such warming conditions along with the water scarcities aggravates the impacts of droughts.[31]

See also

- Effects of climate change on South Asia

- Floods in India

Citations

- Goswami BN, Venugopal V, Sengupta D, Madhusoodanan MS, Xavier PK (2006). "Increasing trend of extreme rain events over India in a warming environment". Science. 314 (5804): 1442–1445. Bibcode:2006Sci...314.1442G. doi:10.1126/science.1132027. PMID 17138899.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Balfour 1976, p. 995.

- Allaby 1998, p. 26.

- Allaby 1998, p. 42.

- Allaby 1998, p. 15.

- Roxy, Mathew Koll; Ritika, Kapoor; Terray, Pascal; Murtugudde, Raghu; Ashok, Karumuri; Goswami, B. N. (2015-06-16). "Drying of Indian subcontinent by rapid Indian Ocean warming and a weakening land-sea thermal gradient". Nature Communications. 6: 7423. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.7423R. doi:10.1038/ncomms8423. PMID 26077934.

- Roxy, Mathew Koll; Ritika, Kapoor; Terray, Pascal; Masson, Sébastien (2014-09-11). "The Curious Case of Indian Ocean Warming" (PDF). Journal of Climate. 27 (22): 8501–8509. Bibcode:2014JCli...27.8501R. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00471.1. ISSN 0894-8755.

- Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: When is hurricane season?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: What are the average, most, and least tropical cyclones occurring in each basin?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- "Tropical Cyclone 05B" (PDF). Naval Maritime Forecast Center (Joint Typhoon Warning Center). Retrieved 2007-04-08.

- "1999 Supercyclone of Orissa". BAPS Care International. 2005. Retrieved 2007-04-08.

- "2020 Supercyclone Amphhan". 2020.

- "US Dollar".

- http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/india-climate-5-water-DEFRA.pdf

- Sathaye, Jayant; Shukla, Priyadarshi; H. Ravindranath, N (30 November 2005). "Climate change, sustainable development and India: Global and national concerns". Curr Sci. 90 – via ResearchGate.

- http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/cc10.pdf

- "India: Climate Change Impacts".

- "India will be the hotspot of water crisis by 2025: UN". www.indiawaterportal.org.

- http://www.saded.in/PDF%20Files/Kulkarni_GW_Effect_HimalayanGlaciers_Shrinkage.pdf

- "Sinking Sundarbans islands underline climate crisis". 17 January 2018.

- Sarkar, uttam; Borah, Bibha (28 June 2017). "Flood plain wetland fisheries of India: with special reference to impact of climate change". Wetlands Ecology and Management. 26: 1–15. doi:10.1007/s11273-017-9559-6 – via ResearchGate.

- Hoegh-Guldberg, Ove; Poloczanska, Elvira S.; Skirving, William; Dove, Sophie (8 June 2018). "Coral Reef Ecosystems under Climate Change and Ocean Acidification". Frontiers in Marine Science. 4. doi:10.3389/fmars.2017.00158.

- "10.4.3 Coastal and low lying areas – AR4 WGII Chapter 10: Asia". www.ipcc.ch.

- https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/22062/1/MPRA_paper_22062.pdf

- Sun, Yuan; Zhong, Zhong; Li, Tim; Yi, Lan; Hu, Yijia; Wan, Hongchao; Chen, Haishan; Liao, Qianfeng; Ma, Chen; Li, Qihua (15 August 2017). "Impact of Ocean Warming on Tropical Cyclone Size and Its Destructiveness". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 8154. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.8154S. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08533-6. PMC 5557849. PMID 28811627.

- Ravindranath, Nijavalli H.; Sathaye, Jayant A. (11 April 2006). Climate Change and Developing Countries. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9780306479809 – via Google Books.

- France-Presse, Agence (20 May 2016). "India records its hottest day ever as temperature hits 51C (that's 123.8F)". the Guardian.

- "India's killer heatwaves claim 4620 deaths in last four years". 23 April 2017.

- "Effects of climate change: If global warming continues, summers in India could last for 8 months by 2070, say researchers – Firstpost". www.firstpost.com.

- "Dust storms may increase in India due to climate change". india.mongabay.com. 2018-05-08.

- Swain, S; et al. (2017). "Application of SPI, EDI and PNPI using MSWEP precipitation data over Marathwada, India". IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS). 2017: 5505–5507. doi:10.1109/IGARSS.2017.8128250. ISBN 978-1-5090-4951-6.

Further reading

- Toman, MA; Chakravorty, U; Gupta, S (2003). India and Global Climate Change: Perspectives on Economics and Policy from a Developing Country. Resources for the Future Press. ISBN 978-1-891853-61-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Atlas of India. |

- General overview

- "Country Guide: India". BBC Weather.

- "India—Weather and Climate". High Commission of India, London.

- Reports

- Resources on Natural Disasters

- Maps, imagery, and statistics

- "India Meteorological Department". Government of India.

- "Weather Resource System for India". National Informatics Centre.

- Forecasts