Climate change and agriculture

Climate change and agriculture are interrelated processes, both of which take place on a global scale. Global warming affects agriculture in a number of ways, including through changes in average temperatures, rainfall, and climate extremes (e.g., heat waves); changes in pests and diseases; changes in atmospheric carbon dioxide and ground-level ozone concentrations; changes in the nutritional quality of some foods;[2] and changes in sea level.[3]

Climate change is already affecting agriculture, with effects unevenly distributed across the world.[4] Future climate change will likely negatively affect crop production in low latitude countries, while effects in northern latitudes may be positive or negative.[4] Animal agriculture is also responsible for CO

2 greenhouse gas production and a percentage of the world's methane, and future land infertility, and the displacement of local species.

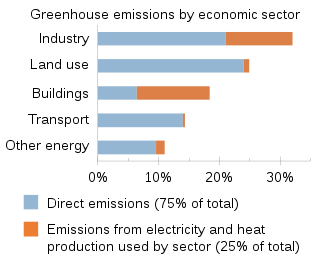

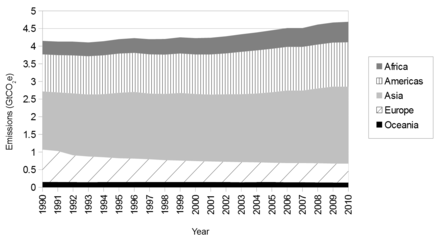

Agriculture contributes to climate change both by anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases and by the conversion of non-agricultural land such as forests into agricultural land.[5][6] In 2010, agriculture, forestry and land-use change were estimated to contribute 20–25% of global annual emissions.[7]. In 2020, the European Union's Scientific Advice Mechanism estimated that the food system as a whole contributed 37% of total greenhouse gas emissions, and that this figure was on course to increase by 30–40% by 2050 due to population growth and dietary change.[8]

A range of policies can reduce the risk of negative climate change impacts on agriculture[9][10] and greenhouse gas emissions from the agriculture sector.[11][12][13]

Impact of climate change on agriculture

.png)

Despite technological advances, such as improved varieties, genetically modified organisms, and irrigation systems, weather is still a key factor in agricultural productivity, as well as soil properties and natural communities. The effect of climate on agriculture is related to variabilities in local climates rather than in global climate patterns. The Earth's average surface temperature has increased by 1.5 °F (0.83 °C) since 1880. Consequently, in making an assessment agronomists must consider each local area.

On the other hand, agricultural trade has grown in recent years, and now provides significant amounts of food, on a national level to major importing countries, as well as comfortable income to exporting ones. The international aspect of trade and security in terms of food implies the need to also consider the effects of climate change on a global scale.

A 2008 study published in Science suggested that, due to climate change, "southern Africa could lose more than 30% of its main crop, maize, by 2030. In South Asia losses of many regional staples, such as rice, millet and maize could top 10%".[15][16]

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has produced several reports that have assessed the scientific literature on climate change. The IPCC Third Assessment Report, published in 2001, concluded that the poorest countries would be hardest hit, with reductions in crop yields in most tropical and sub-tropical regions due to decreased water availability, and new or changed insect pest incidence. In Africa and Latin America many rainfed crops are near their maximum temperature tolerance, so that yields are likely to fall sharply for even small climate changes; falls in agricultural productivity of up to 30% over the 21st century are projected. Marine life and the fishing industry will also be severely affected in some places.

In the report published in 2014 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says that the world may reach "a threshold of global warming beyond which current agricultural practices can no longer support large human civilizations." by the middle of the 21st century. In 2019 it published reports in which it says that millions already suffer from food insecurity due to climate change and predicted decline in global crop production of 2% - 6% by decade.[17][18]

Climate change can reduce yields by the amplification of rossby waves. There is a possibility that the effects are already existing.[19]

Climate change induced by increasing greenhouse gases is likely to affect crops differently from region to region. For example, average crop yield is expected to drop down to 50% in Pakistan according to the Met Office scenario whereas corn production in Europe is expected to grow up to 25% in optimum hydrologic conditions.

More favourable effects on yield tend to depend to a large extent on realization of the potentially beneficial effects of carbon dioxide on crop growth and increase of efficiency in water use. Decrease in potential yields is likely to be caused by shortening of the growing period, decrease in water availability and poor vernalization.

In the long run, the climatic change could affect agriculture in several ways :

- productivity, in terms of quantity and quality of crops

- agricultural practices, through changes of water use (irrigation) and agricultural inputs such as herbicides, insecticides and fertilizers

- environmental effects, in particular in relation of frequency and intensity of soil drainage (leading to nitrogen leaching), soil erosion, reduction of crop diversity

- rural space, through the loss and gain of cultivated lands, land speculation, land renunciation, and hydraulic amenities.

- adaptation, organisms may become more or less competitive, as well as humans may develop urgency to develop more competitive organisms, such as flood resistant or salt resistant varieties of rice.

They are large uncertainties to uncover, particularly because there is lack of information on many specific local regions, and include the uncertainties on magnitude of climate change, the effects of technological changes on productivity, global food demands, and the numerous possibilities of adaptation.

Most agronomists believe that agricultural production will be mostly affected by the severity and pace of climate change, not so much by gradual trends in climate. If change is gradual, there may be enough time for biota adjustment. Rapid climate change, however, could harm agriculture in many countries, especially those that are already suffering from rather poor soil and climate conditions, because there is less time for optimum natural selection and adaption.

But much remains unknown about exactly how climate change may affect farming and food security, in part because the role of farmer behaviour is poorly captured by crop-climate models. For instance, Evan Fraser, a geographer at the University of Guelph in Ontario Canada, has conducted a number of studies that show that the socio-economic context of farming may play a huge role in determining whether a drought has a major, or an insignificant impact on crop production.[20][21] In some cases, it seems that even minor droughts have big impacts on food security (such as what happened in Ethiopia in the early 1980s where a minor drought triggered a massive famine), versus cases where even relatively large weather-related problems were adapted to without much hardship.[22] Evan Fraser combines socio-economic models along with climatic models to identify "vulnerability hotspots"[21] One such study has identified US maize (corn) production as particularly vulnerable to climate change because it is expected to be exposed to worse droughts, but it does not have the socio-economic conditions that suggest farmers will adapt to these changing conditions.[23] Other studies rely instead on projections of key agro-meteorological or agro-climate indices, such as growing season length, plant heat stress, or start of field operations, identified by land management stakeholders and that provide useful information on mechanisms driving climate change impact on agriculture.[24][25]

Pest insects and climate change

Global warming could lead to an increase in pest insect populations, harming yields of staple crops like wheat, soybeans, and corn.[26] While warmer temperatures create longer growing seasons, and faster growth rates for plants, it also increases the metabolic rate and number of breeding cycles of insect populations.[26] Insects that previously had only two breeding cycles per year could gain an additional cycle if warm growing seasons extend, causing a population boom. Temperate places and higher latitudes are more likely to experience a dramatic change in insect populations.[27]

The University of Illinois conducted studies to measure the effect of warmer temperatures on soybean plant growth and Japanese beetle populations.[28] Warmer temperatures and elevated CO2 levels were simulated for one field of soybeans, while the other was left as a control. These studies found that the soybeans with elevated CO2 levels grew much faster and had higher yields, but attracted Japanese beetles at a significantly higher rate than the control field.[28] The beetles in the field with increased CO2 also laid more eggs on the soybean plants and had longer lifespans, indicating the possibility of a rapidly expanding population. DeLucia projected that if the project were to continue, the field with elevated CO2 levels would eventually show lower yields than that of the control field.[28]

The increased CO2 levels deactivated three genes within the soybean plant that normally create chemical defenses against pest insects. One of these defenses is a protein that blocks digestion of the soy leaves in insects. Since this gene was deactivated, the beetles were able to digest a much higher amount of plant matter than the beetles in the control field. This led to the observed longer lifespans and higher egg-laying rates in the experimental field.[28]

There are a few proposed solutions to the issue of expanding pest populations. One proposed solution is to increase the number of pesticides used on future crops.[29] This has the benefit of being relatively cost effective and simple, but may be ineffective. Many pest insects have been building up an immunity to these pesticides. Another proposed solution is to utilize biological control agents.[29] This includes things like planting rows of native vegetation in between rows of crops. This solution is beneficial in its overall environmental impact. Not only are more native plants getting planted, but pest insects are no longer building up an immunity to pesticides. However, planting additional native plants requires more room, which destroys additional acres of public land. The cost is also much higher than simply using pesticides.[30]

Plant diseases and climate change

Although research is limited, research has shown that climate change may alter the developmental stages of pathogens that can affect crops.[31] The biggest consequence of climate change on the dispersal of pathogens is that the geographical distribution of hosts and pathogens could shift, which would result in more crop losses.[31] This could affect competition and recovery from disturbances of plants. It has been predicted that the effect of climate change will add a level of complexity to figuring out how to maintain sustainable agriculture.[31]

Observed impacts

Effects of regional climate change on agriculture have been limited.[32] Changes in crop phenology provide important evidence of the response to recent regional climate change.[33] Phenology is the study of natural phenomena that recur periodically, and how these phenomena relate to climate and seasonal changes.[34] A significant advance in phenology has been observed for agriculture and forestry in large parts of the Northern Hemisphere.[32]

Droughts have been occurring more frequently because of global warming and they are expected to become more frequent and intense in Africa, southern Europe, the Middle East, most of the Americas, Australia, and Southeast Asia.[35] Their impacts are aggravated because of increased water demand, population growth, urban expansion, and environmental protection efforts in many areas.[36] Droughts result in crop failures and the loss of pasture grazing land for livestock.[37]

Examples

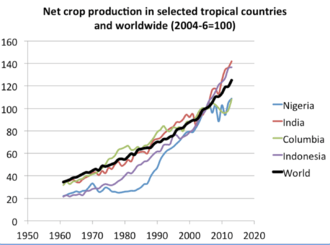

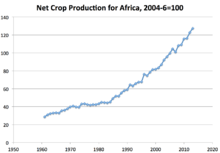

As of the decade starting in 2010, many hot countries have thriving agricultural sectors.

Jalgaon district, India, has an average temperature which ranges from 20.2 °C in December to 29.8 °C in May, and an average precipitation of 750 mm/year.[38] It produces bananas at a rate that would make it the world's seventh-largest banana producer if it were a country.[39]

During the period 1990–2012, Nigeria had an average temperature which ranged from a low of 24.9 °C in January to a high of 30.4 °C in April.[40] According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Nigeria is by far the world's largest producer of yams, producing over 38 million tonnes in 2012. The second through 8th largest yam producers were all nearby African countries, with the largest non-African producer, Papua New Guinea, producing less than 1% of Nigerian production.[41]

In 2013, according to the FAO, Brazil and India were by far the world's leading producers of sugarcane, with a combined production of over 1 billion tonnes, or over half of worldwide production.[42]

In the summer of 2018, heat waves probably linked to climate change cause much lower than average yield in many parts of the world, especially in Europe. Depending on conditions during August, more crop failures could rise global food prices.[43] losses are compared to those of 1945, the worst harvest in memory. last year was the third time in four years that global wheat, rice and maize production failed to meet demand, forcing governments and food companies to release stocks from storage. India last week released 50% of its food stocks. Lester Brown, the head of Worldwatch, an independent research organisation, predicted that food prices will rise in the next few months.

According to the UN report "Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems",[44][45] food prices will rise by 80% by 2050 and food shortages are likely to occur. Some authors also suggested that the food shortages will probably affect poorer parts of the world far more than richer ones

To prevent hunger, instability, new waves of climate refugees, international help will be needed to countries who will miss the money to buy enough food and for also for stopping conflicts.[46][47](see also Climate change adaptation).

At the beginning of the 21 century, floods probably linked to climate change shortened the planting season in the Midwest region in United States, what cause damage to the agriculture sector. In May 2019 the floods reduced the projected corn yield from 15 billion bushels to 14.2.[48]

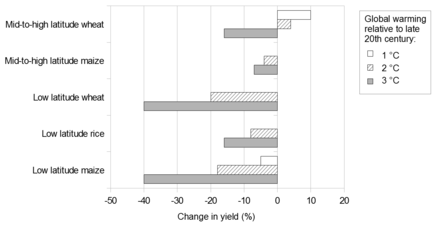

Projections of impacts

As part of the IPCC's Fourth Assessment Report, Schneider et al. (2007) projected the potential future effects of climate change on agriculture.[49] With low to medium confidence, they concluded that for about a 1 to 3 °C global mean temperature increase (by 2100, relative to the 1990–2000 average level) there would be productivity decreases for some cereals in low latitudes, and productivity increases in high latitudes. In the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, "low confidence" means that a particular finding has about a 2 out of 10 chance of being correct, based on expert judgement. "Medium confidence" has about a 5 out of 10 chance of being correct.[50] Over the same time period, with medium confidence, global production potential was projected to:[49]

- increase up to around 3 °C,

- very likely decrease above about 3 °C.

Most of the studies on global agriculture assessed by Schneider et al. (2007) had not incorporated a number of critical factors, including changes in extreme events, or the spread of pests and diseases. Studies had also not considered the development of specific practices or technologies to aid adaptation to climate change.[51]

The US National Research Council (US NRC, 2011)[52] assessed the literature on the effects of climate change on crop yields. US NRC (2011)[53] stressed the uncertainties in their projections of changes in crop yields. A meta-analysis in 2014 revealed consensus that yield is expected to decrease in the second half of the century, and with greater effect in tropical than temperate regions.[54]

Writing in the journal Nature Climate Change, Matthew Smith and Samuel Myers (2018) estimated that food crops could see a reduction of protein, iron and zinc content in common food crops of 3 to 17%.[55] This is the projected result of food grown under the expected atmospheric carbon-dioxide levels of 2050. Using data from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization as well as other public sources, the authors analyzed 225 different staple foods, such as wheat, rice, maize, vegetables, roots and fruits.[56] The effect of projected for this century levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide on the nutritional quality of plants is not limited only to the above-mentioned crop categories and nutrients. A 2014 meta-analysis has shown that crops and wild plants exposed to elevated carbon dioxide levels at various latitudes have lower density of several minerals such as magnesium, iron, zinc, and potassium.[57]

Projected changes in crop yields at different latitudes with global warming. This graph is based on several studies.[52] |

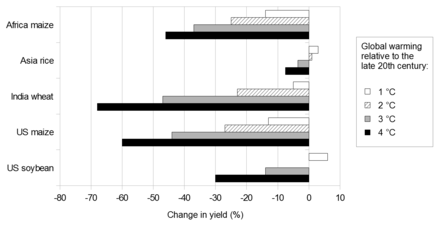

Projected changes in yields of selected crops with global warming. This graph is based on several studies.[52] |

Their central estimates of changes in crop yields are shown above. Actual changes in yields may be above or below these central estimates.[53] US NRC (2011)[52] also provided an estimated the "likely" range of changes in yields. "Likely" means a greater than 67% chance of being correct, based on expert judgement. The likely ranges are summarized in the image descriptions of the two graphs.

Food security

The IPCC Fourth Assessment Report also describes the impact of climate change on food security.[58] Projections suggested that there could be large decreases in hunger globally by 2080, compared to the (then-current) 2006 level.[59] Reductions in hunger were driven by projected social and economic development. For reference, the Food and Agriculture Organization has estimated that in 2006, the number of people undernourished globally was 820 million.[60] Three scenarios without climate change (SRES A1, B1, B2) projected 100-130 million undernourished by the year 2080, while another scenario without climate change (SRES A2) projected 770 million undernourished. Based on an expert assessment of all of the evidence, these projections were thought to have about a 5-in-10 chance of being correct.[50]

The same set of greenhouse gas and socio-economic scenarios were also used in projections that included the effects of climate change.[59] Including climate change, three scenarios (SRES A1, B1, B2) projected 100-380 million undernourished by the year 2080, while another scenario with climate change (SRES A2) projected 740–1,300 million undernourished. These projections were thought to have between a 2-in-10 and 5-in-10 chance of being correct.[50]

Projections also suggested regional changes in the global distribution of hunger.[59] By 2080, sub-Saharan Africa may overtake Asia as the world's most food-insecure region. This is mainly due to projected social and economic changes, rather than climate change.[58]

In South America, a phenomenon known as the El Nino Oscillation Cycle, between floods and drought on the Pacific Coast has made as much as a 35% difference in Global yields of wheat and grain.[61]

Looking at the four key components of food security we can see the impact climate change has had. "Access to food is largely a matter of household and individual-level income and of capabilities and rights" (Wheeler et al.,2013). Access has been affected by the thousands of crops being destroyed, how communities are dealing with climate shocks and adapting to climate change. Prices on food will rise due to the shortage of food production due to conditions not being favourable for crop production. Utilization is affected by floods and drought where water resources are contaminated, and the changing temperatures create vicious stages and phases of disease. Availability is affected by the contamination of the crops, as there will be no food process for the products of these crops as a result. Stability is affected through price ranges and future prices as some food sources are becoming scarce due to climate change, so prices will rise.

Individual studies

.png)

Cline (2008)[62] looked at how climate change might affect agricultural productivity in the 2080s. His study assumes that no efforts are made to reduce anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, leading to global warming of 3.3 °C above the pre-industrial level. He concluded that global agricultural productivity could be negatively affected by climate change, with the worst effects in developing countries (see graph opposite).

Lobell et al. (2008a)[63] assessed how climate change might affect 12 food-insecure regions in 2030. The purpose of their analysis was to assess where adaptation measures to climate change should be prioritized. They found that without sufficient adaptation measures, South Asia and South Africa would likely suffer negative impacts on several crops which are important to large food insecure human populations.

Battisti and Naylor (2009)[64] looked at how increased seasonal temperatures might affect agricultural productivity. Projections by the IPCC suggest that with climate change, high seasonal temperatures will become widespread, with the likelihood of extreme temperatures increasing through the second half of the 21st century. Battisti and Naylor (2009)[64] concluded that such changes could have very serious effects on agriculture, particularly in the tropics. They suggest that major, near-term, investments in adaptation measures could reduce these risks.

"Climate change merely increases the urgency of reforming trade policies to ensure that global food security needs are met"[65] said C. Bellmann, ICTSD Programmes Director. A 2009 ICTSD-IPC study by Jodie Keane[66] suggests that climate change could cause farm output in sub-Saharan Africa to decrease by 12% by 2080 - although in some African countries this figure could be as much as 60%, with agricultural exports declining by up to one fifth in others. Adapting to climate change could cost the agriculture sector $14bn globally a year, the study finds.

Regional impacts

Africa

Agriculture is a particularly important sector in Africa, contributing towards livelihoods and economies across the continent. On average, agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa contributes 15% of the total GDP.[68] Africa's geography makes it particularly vulnerable to climate change, and seventy per cent of the population rely on rain-fed agriculture for their livelihoods. Smallholder farms account for 80% of cultivated lands in sub-Saharan Africa.[68] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2007:13)[69] projected that climate variability and change would severely compromise agricultural production and access to food. This projection was assigned "high confidence". Cropping systems, livestock and fisheries will be at greater risk of pest and diseases as a result of future climate change.[70] Research program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) have identified that crop pests already account for approximately 1/6th of farm productivity losses.[70] Similarly, climate change will accelerate the prevalence of pests and diseases and increase the occurrence of highly impactful events.[70] The impacts of climate change on agricultural production in Africa will have serious implications for food security and livelihoods. Between 2014 and 2018, Africa had the highest levels of food insecurity in the world.[71]

East Africa

In East Africa, climate change is anticipated to intensify the frequency and intensity of drought and flooding, which can have an adverse impact on the agricultural sector. Climate change will have varying effects on agricultural production in East Africa. Research from the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) suggest an increase in maize yields for most East Africa, but yield losses in parts of Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Tanzania and northern Uganda.[72] Projections of climate change are also anticipated to reduce the potential of the cultivated land to produce crops of high quantity and quality.[73]

In Tanzania there is currently no clear signal in future climate projections for rainfall.[74] However, there is a higher likelihood of intense future rainfall events.[74] As of 2005, the net result was expected to be that 33% less maize—the country's staple crop—would be grown.[75]

Southern Africa

Climate change will exacerbate the vulnerability of the Agricultural sector in most Southern African countries which are already limited by poor infrastructure and a lag in technological inputs and innovation.[76] Maize accounts for nearly half of the cultivated land in Southern Africa, and under future climate change, yields could decrease by 30%[77] Temperatures increases also encourage a wide spread of weeds and pests[78] In December 2019, 45 million peoples in southern Africa required help because of crop failure. The drought reduces the water stream in Victoria falls by 50%. The droughts became more frequent in the region.[79]

West Africa

Climate change will significantly affect agriculture in West Africa by increasing the variability in food production, access and availability.[80] The region has already experienced a decrease in rainfall along the coasts of Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia.[81] This has resulted in lower crop yield, causing farmers to seek new areas for cultivation.[82] Staple crops such as maize, rice and sorghum will be impacted by low rainfall events with possible increase in food insecurity.[83]

Central Africa

Higher rainfall intensity, prolonged dry spells and high temperatures are expected to negatively impact cassava, maize and bean production in Central Africa.[84] Floods and erosion occurrence are expected to damage the already limited transportation infrastructure in the region leading to post harvest losses.[84] Exportation of economic crops like coffee and cocoa are on the rise within the region but these crops are highly vulnerable to climate change.[84] Conflicts and political instability have had an impact on agriculture contribution to the regional GDP and this impact will be exacerbated by climatic risks.[85]

Asia

In East and Southeast Asia, IPCC (2007:13)[69] projected that crop yields could increase up to 20% by the mid-21st century. In Central and South Asia, projections suggested that yields might decrease by up to 30%, over the same time period. These projections were assigned "medium confidence." Taken together, the risk of hunger was projected to remain very high in several developing countries.

More detailed analysis of rice yields by the International Rice Research Institute forecast 20% reduction in yields over the region per degree Celsius of temperature rise. Rice becomes sterile if exposed to temperatures above 35 degrees for more than one hour during flowering and consequently produces no grain.[86][87]

A 2013 study by the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) aimed to find science-based, pro-poor approaches and techniques that would enable Asia's agricultural systems to cope with climate change, while benefitting poor and vulnerable farmers. The study's recommendations ranged from improving the use of climate information in local planning and strengthening weather-based agro-advisory services, to stimulating diversification of rural household incomes and providing incentives to farmers to adopt natural resource conservation measures to enhance forest cover, replenish groundwater and use renewable energy.[88] A 2014 study found that warming had increased maize yields in the Heilongjiang region of China had increased by between 7 and 17% per decade as a result of rising temperatures.[89]

Due to climate change, livestock production will be decreased in Bangladesh by diseases, scarcity of forage, heat stress and breeding strategies.[90]

These issues dealing with agriculture are important to consider because countries in Asia rely on this sector for exports for other countries. This in turn contributes to more land degradation to keep up with this global demand which in turn causes cascading environmental effects. Environmental factor#Socioeconomic Drivers

Australia and New Zealand

Hennessy et al.. (2007:509)[91] assessed the literature for Australia and New Zealand. They concluded that without further adaptation to climate change, projected impacts would likely be substantial: By 2030, production from agriculture and forestry was projected to decline over much of southern and eastern Australia, and over parts of eastern New Zealand; In New Zealand, initial benefits were projected close to major rivers and in western and southern areas. Hennessy et al.. (2007:509)[91] placed high confidence in these projections.

Europe

With high confidence, IPCC (2007:14)[69] projected that in Southern Europe, climate change would reduce crop productivity. In Central and Eastern Europe, forest productivity was expected to decline. In Northern Europe, the initial effect of climate change was projected to increase crop yields. The 2019 European Environment Agency report "Climate change adaptation in the agricultural sector in Europe" again confirmed this. According to this 2019 report, projections indicate that yields of non-irrigated crops like wheat, corn and sugar beet would decrease in southern Europe by up to 50% by 2050 (under a high-end emission scenario). This could result in a substantial decrease in farm income by that date. Also farmland values are projected to decrease in parts of southern Europe by more than 80% by 2100, which could result in land abandonment. The trade patterns are also said to be impacted, in turn affecting agricultural income. Also, increased food demand worldwide could exert pressure on food prices in the coming decades.[92]

In 2020, the European Union's Scientific Advice Mechanism published a detailed review of the EU's policies related to the food system, especially the Common Agricultural Policy and the Common Fisheries Policy, in relation to their sustainability.[93]

Latin America

The major agricultural products of Latin American regions include livestock and grains, such as maize, wheat, soybeans, and rice.[94][95] Increased temperatures and altered hydrological cycles are predicted to translate to shorter growing seasons, overall reduced biomass production, and lower grain yields.[95][96] Brazil, Mexico and Argentina alone contribute 70-90% of the total agricultural production in Latin America.[95] In these and other dry regions, maize production is expected to decrease.[94][95] A study summarizing a number of impact studies of climate change on agriculture in Latin America indicated that wheat is expected to decrease in Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay.[95] Livestock, which is the main agricultural product for parts of Argentina, Uruguay, southern Brazil, Venezuela, and Colombia is likely to be reduced.[94][95] Variability in the degree of production decrease among different regions of Latin America is likely.[94] For example, one 2003 study that estimated future maize production in Latin America predicted that by 2055 maize in eastern Brazil will have moderate changes while Venezuela is expected to have drastic decreases.[94]

Suggested potential adaptation strategies to mitigate the impacts of global warming on agriculture in Latin America include using plant breeding technologies and installing irrigation infrastructure.[95]

Climate justice and subsistence farmers in Latin America

Several studies that investigated the impacts of climate change on agriculture in Latin America suggest that in the poorer countries of Latin America, agriculture composes the most important economic sector and the primary form of sustenance for small farmers.[94][95][96][97] Maize is the only grain still produced as a sustenance crop on small farms in Latin American nations.[95] Scholars argue that the projected decrease of this grain and other crops will threaten the welfare and the economic development of subsistence communities in Latin America.[94][95][96] Food security is of particular concern to rural areas that have weak or non-existent food markets to rely on in the case food shortages.[98]

According to scholars who considered the environmental justice implications of climate change, the expected impacts of climate change on subsistence farmers in Latin America and other developing regions are unjust for two reasons.[97][99] First, subsistence farmers in developing countries, including those in Latin America are disproportionately vulnerable to climate change[99] Second, these nations were the least responsible for causing the problem of anthropogenic induced climate.[99]

According to researchers John F. Morton and T. Roberts, disproportionate vulnerability to climate disasters is socially determined.[97][99] For example, socioeconomic and policy trends affecting smallholder and subsistence farmers limit their capacity to adapt to change.[97] According to W. Baethgen who studied the vulnerability of Latin American agriculture to climate change, a history of policies and economic dynamics has negatively impacted rural farmers.[95] During the 1950s and through the 1980s, high inflation and appreciated real exchange rates reduced the value of agricultural exports.[95] As a result, farmers in Latin America received lower prices for their products compared to world market prices.[95] Following these outcomes, Latin American policies and national crop programs aimed to stimulate agricultural intensification.[95] These national crop programs benefitted larger commercial farmers more. In the 1980s and 1990s low world market prices for cereals and livestock resulted in decreased agricultural growth and increased rural poverty.[95]

In the book, Fairness in Adaptation to Climate Change, the authors describe the global injustice of climate change between the rich nations of the north, who are the most responsible for global warming and the southern poor countries and minority populations within those countries who are most vulnerable to climate change impacts.[99]

Adaptive planning is challenged by the difficulty of predicting local scale climate change impacts.[97] An expert that considered opportunities for climate change adaptation for rural communities argues that a crucial component to adaptation should include government efforts to lessen the effects of food shortages and famines.[100] This researcher also claims that planning for equitable adaptation and agricultural sustainability will require the engagement of farmers in decision making processes.[100]

North America

A number of studies have been produced which assess the impacts of climate change on agriculture in North America. The IPCC Fourth Assessment Report of agricultural impacts in the region cites 26 different studies.[101] With high confidence, IPCC (2007:14–15)[69] projected that over the first few decades of this century, moderate climate change would increase aggregate yields of rain-fed agriculture by 5–20%, but with important variability among regions. Major challenges were projected for crops that are near the warm end of their suitable range or which depend on highly utilized water resources.

Droughts are becoming more frequent and intense in arid and semiarid western North America as temperatures have been rising, advancing the timing and magnitude of spring snow melt floods and reducing river flow volume in summer.[102] Direct effects of climate change include increased heat and water stress, altered crop phenology, and disrupted symbiotic interactions. These effects may be exacerbated by climate changes in river flow, and the combined effects are likely to reduce the abundance of native trees in favour of non-native herbaceous and drought-tolerant competitors, reduce the habitat quality for many native animals, and slow litter decomposition and nutrient cycling. Climate change effects on human water demand and irrigation may intensify these effects.[103]

The US Global Change Research Program (2009) assessed the literature on the impacts of climate change on agriculture in the United States, finding that many crops will benefit from increased atmospheric CO

2 concentrations and low levels of warming, but that higher levels of warming will negatively affect growth and yields; that extreme weather events will likely reduce crop yields; that weeds, diseases and insect pests will benefit from warming, and will require additional pest and weed control; and that increasing CO

2 concentrations will reduce the land's ability to supply adequate livestock feed, while increased heat, disease, and weather extremes will likely reduce livestock productivity.[104]

Polar regions

Anisimov et al.. (2007:655)[105] assessed the literature for the polar region (Arctic and Antarctica). With medium confidence, they concluded that the benefits of a less severe climate were dependent on local conditions. One of these benefits was judged to be increased agricultural and forestry opportunities.

The Guardian reported on how climate change had affected agriculture in Iceland. Rising temperatures had made the widespread sowing of barley possible, which had been untenable twenty years ago. Some of the warming was due to a local (possibly temporary) effect via ocean currents from the Caribbean, which had also affected fish stocks.[106]

Small islands

In a literature assessment, Mimura et al. (2007:689)[107] concluded that on small islands, subsistence and commercial agriculture would very likely be adversely affected by climate change. This projection was assigned "high confidence."

Climate change impacts affecting poverty alleviation

Researchers at the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) have investigated the potential impacts climate change could have on agriculture, and how this would affect attempts at alleviating poverty in the developing world.[108] They argued that the effects from moderate climate change are likely to be mixed for developing countries. However, the vulnerability of the poor in developing countries to short-term impacts from climate change, notably the increased frequency and severity of adverse weather events is likely to have a negative impact. This, they say, should be taken into account when defining agricultural policy.[108]

Crop development models

Models for climate behavior are frequently inconclusive. In order to further study effects of global warming on agriculture, other types of models, such as crop development models, yield prediction, quantities of water or fertilizer consumed, can be used. Such models condense the knowledge accumulated of the climate, soil, and effects observed of the results of various agricultural practices. They thus could make it possible to test strategies of adaptation to modifications of the environment.

Because these models are necessarily simplifying natural conditions (often based on the assumption that weeds, disease and insect pests are controlled), it is not clear whether the results they give will have an in-field reality. However, some results are partly validated with an increasing number of experimental results.

Other models, such as insect and disease development models based on climate projections are also used (for example simulation of aphid reproduction or septoria (cereal fungal disease) development).

Scenarios are used in order to estimate climate changes effects on crop development and yield. Each scenario is defined as a set of meteorological variables, based on generally accepted projections. For example, many models are running simulations based on doubled carbon dioxide projections, temperatures raise ranging from 1 °C up to 5 °C, and with rainfall levels an increase or decrease of 20%. Other parameters may include humidity, wind, and solar activity. Scenarios of crop models are testing farm-level adaptation, such as sowing date shift, climate adapted species (vernalisation need, heat and cold resistance), irrigation and fertilizer adaptation, resistance to disease. Most developed models are about wheat, maize, rice and soybean.

Temperature potential effect on growing period

Duration of crop growth cycles are above all, related to temperature. An increase in temperature will speed up development.[109] In the case of an annual crop, the duration between sowing and harvesting will shorten (for example, the duration in order to harvest corn could shorten between one and four weeks). The shortening of such a cycle could have an adverse effect on productivity because senescence would occur sooner.[110]

Effect of elevated carbon dioxide on crops

Elevated atmospheric carbon dioxide affects plants in a variety of ways. Elevated CO2 increases crop yields and growth through an increase in photosynthetic rate, and it also decreases water loss as a result of stomatal closing.[111] It limits the vaporization of water reaching the stem of the plant. "Crassulacean Acid Metabolism" oxygen is all along the layer of the leaves for each plant leaves taking in CO2and release O2. The growth response is greatest in C3 plants, C4 plants, are also enhanced but to a lesser extent, and CAM Plants are the least enhanced species.[112] The stoma in these "CAM plant" stores remain shut all day to reduce exposure. rapidly rising levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere affect plants' absorption of nitrogen, which is the nutrient that restricts crop growth in most terrestrial ecosystems. Today's concentration of 400 ppm plants are relatively starved for nutrition. The optimum level of CO2 for plant growth is about 5 times higher. Increased mass of CO2 increases photosynthesis, this CO2 potentially stunts the growth of the plant. It limit's the reduction that crops lose through transpiration.

Increase in global temperatures will cause an increase in evaporation rates and annual evaporation levels. Increased evaporation will lead to an increase in storms in some areas, while leading to accelerated drying of other areas. These storm impacted areas will likely experience increased levels of precipitation and increased flood risks, while areas outside of the storm track will experience less precipitation and increased risk of droughts.[113] Water stress affects plant development and quality in a variety of ways first off drought can cause poor germination and impaired seedling development in plants.[114] At the same time plant growth relies on cellular division, cell enlargement, and differentiation. Drought stress impairs mitosis and cell elongation via loss of turgor pressure which results in poor growth.[115] Development of leaves is also dependent upon turgor pressure, concentration of nutrients, and carbon assimilates all of which are reduced by drought conditions, thus drought stress lead to a decrease in leaf size and number.[115] Plant height, biomass, leaf size and stem girth has been shown to decrease in Maize under water limiting conditions.[115] Crop yield is also negatively effected by drought stress, the reduction in crop yield results from a decrease in photosynthetic rate, changes in leaf development, and altered allocation of resources all due to drought stress.[115] Crop plants exposed to drought stress suffer from reductions in leaf water potential and transpiration rate, however water-use efficiency has been shown to increase in some crop plants such as wheat while decreasing in others such as potatoes.[116][117][115] Plants need water for the uptake of nutrients from the soil, and for the transport of nutrients throughout the plant, drought conditions limit these functions leading to stunted growth. Drought stress also causes a decrease in photosynthetic activity in plants due to the reduction of photosynthetic tissues, stomatal closure, and reduced performance of photosynthetic machinery. This reduction in photosynthetic activity contributes to the reduction in plant growth and yields.[115] Another factor influencing reduced plant growth and yields include the allocation of resources; following drought stress plants will allocate more resources to roots to aid in water uptake increasing root growth and reducing the growth of other plant parts while decreasing yields.[115]

Effect on quality

According to the IPCC's TAR, "The importance of climate change impacts on grain and forage quality emerges from new research. Climate change can alter the adequacy ratios for specific macronutrients, carbohydrates and protein.[118] For rice, the amylose content of the grain—a major determinant of cooking quality—is increased under elevated CO2" (Conroy et al., 1994). Cooked rice grain from plants grown in high-CO

2 environments would be firmer than that from today's plants. However, concentrations of iron and zinc, which are important for human nutrition, would be lower (Seneweera and Conroy, 1997). Moreover, the protein content of the grain decreases under combined increases of temperature and CO2 (Ziska et al., 1997).[119] Studies using FACE have shown that increases in CO2 lead to decreased concentrations of micronutrients in crop and non-crop plants with negative consequences for human nutrition,[120][57] including decreased B vitamins in rice.[121][122] This may have knock-on effects on other parts of ecosystems as herbivores will need to eat more food to gain the same amount of protein.[123]

Studies have shown that higher CO2 levels lead to reduced plant uptake of nitrogen (and a smaller number showing the same for trace elements such as zinc) resulting in crops with lower nutritional value.[124][125][126] This would primarily impact on populations in poorer countries less able to compensate by eating more food, more varied diets, or possibly taking supplements.

Reduced nitrogen content in grazing plants has also been shown to reduce animal productivity in sheep, which depend on microbes in their gut to digest plants, which in turn depend on nitrogen intake.[124] Because of the lack of water available to crops in warmer countries they struggle to survive as they suffer from dehydration, taking into account the increasing demand for water outside of agriculture as well as other agricultural demands.[127]

Effect of hail

In North America, fewer hail days will occur overall due to climate change, but storms with larger hail might become more common (including hail that is larger than 1.6-inch).[128][129][128] Hail that is larger than 1.6-inch can quite easily break (glass) greenhouses.[130]

Agricultural surfaces and climate changes

Climate change may increase the amount of arable land in high-latitude region by reduction of the amount of frozen lands. A 2005 study reports that temperature in Siberia has increased three-degree Celsius in average since 1960 (much more than the rest of the world).[131] However, reports about the impact of global warming on Russian agriculture[132] indicate conflicting probable effects: while they expect a northward extension of farmable lands,[133] they also warn of possible productivity losses and increased risk of drought.[134]

Sea levels are expected to get up to one meter higher by 2100, though this projection is disputed. A rise in the sea level would result in an agricultural land loss, in particular in areas such as South East Asia. Erosion, submergence of shorelines, salinity of the water table due to the increased sea levels, could mainly affect agriculture through inundation of low-lying lands.

Low-lying areas such as Bangladesh, India and Vietnam will experience major loss of rice crop if sea levels rise as expected by the end of the century. Vietnam for example relies heavily on its southern tip, where the Mekong Delta lies, for rice planting. Any rise in sea level of no more than a meter will drown several km2 of rice paddies, rendering Vietnam incapable of producing its main staple and export of rice.[135]

Erosion and fertility

The warmer atmospheric temperatures observed over the past decades are expected to lead to a more vigorous hydrological cycle, including more extreme rainfall events. Erosion and soil degradation is more likely to occur. Soil fertility would also be affected by global warming. Increased erosion in agricultural landscapes from anthropogenic factors can occur with losses of up to 22% of soil carbon in 50 years.[136] However, because the ratio of soil organic carbon to nitrogen is mediated by soil biology such that it maintains a narrow range, a doubling of soil organic carbon is likely to imply a doubling in the storage of nitrogen in soils as organic nitrogen, thus providing higher available nutrient levels for plants, supporting higher yield potential. The demand for imported fertilizer nitrogen could decrease, and provide the opportunity for changing costly fertilisation strategies.

Due to the extremes of climate that would result, the increase in precipitations would probably result in greater risks of erosion, whilst at the same time providing soil with better hydration, according to the intensity of the rain. The possible evolution of the organic matter in the soil is a highly contested issue: while the increase in the temperature would induce a greater rate in the production of minerals, lessening the soil organic matter content, the atmospheric CO2 concentration would tend to increase it.

Potential effects of global climate change on pests, diseases and weeds

A very important point to consider is that weeds would undergo the same acceleration of cycle as cultivated crops, and would also benefit from carbonaceous fertilization. Since most weeds are C3 plants, they are likely to compete even more than now against C4 crops such as corn. However, on the other hand, some results make it possible to think that weedkillers could increase in effectiveness with the temperature increase.[137]

Global warming would cause an increase in rainfall in some areas, which would lead to an increase of atmospheric humidity and the duration of the wet seasons. Combined with higher temperatures, these could favour the development of fungal diseases. Similarly, because of higher temperatures and humidity, there could be an increased pressure from insects and disease vectors.

Glacier retreat and disappearance

The continued retreat of glaciers will have a number of different quantitative impacts. In the areas that are heavily dependent on water runoff from glaciers that melt during the warmer summer months, a continuation of the current retreat will eventually deplete the glacial ice and substantially reduce or eliminate runoff. A reduction in runoff will affect the ability to irrigate crops and will reduce summer stream flows necessary to keep dams and reservoirs replenished.

Approximately 2.4 billion people live in the drainage basin of the Himalayan rivers.[138] India, China, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Myanmar could experience floods followed by severe droughts in coming decades.[139] In India alone, the Ganges provides water for drinking and farming for more than 500 million people.[140][141] The west coast of North America, which gets much of its water from glaciers in mountain ranges such as the Rocky Mountains and Sierra Nevada, also would be affected.[142]

Ozone and UV-B

Some scientists think agriculture could be affected by any decrease in stratospheric ozone, which could increase biologically dangerous ultraviolet radiation B. Excess ultraviolet radiation B can directly affect plant physiology and cause massive amounts of mutations, and indirectly through changed pollinator behavior, though such changes are not simple to quantify.[143] However, it has not yet been ascertained whether an increase in greenhouse gases would decrease stratospheric ozone levels.

In addition, a possible effect of rising temperatures is significantly higher levels of ground-level ozone, which would substantially lower yields.[144]

ENSO effects on agriculture

ENSO (El Niño Southern Oscillation) will affect monsoon patterns more intensely in the future as climate change warms up the ocean's water. Crops that lie on the equatorial belt or under the tropical Walker circulation, such as rice, will be affected by varying monsoon patterns and more unpredictable weather. Scheduled planting and harvesting based on weather patterns will become less effective.

Areas such as Indonesia where the main crop consists of rice will be more vulnerable to the increased intensity of ENSO effects in the future of climate change. University of Washington professor, David Battisti, researched the effects of future ENSO patterns on the Indonesian rice agriculture using [IPCC]'s 2007 annual report[145] and 20 different logistical models mapping out climate factors such as wind pressure, sea-level, and humidity, and found that rice harvest will experience a decrease in yield. Bali and Java, which holds 55% of the rice yields in Indonesia, will be likely to experience 9–10% probably of delayed monsoon patterns, which prolongs the hungry season. Normal planting of rice crops begin in October and harvest by January. However, as climate change affects ENSO and consequently delays planting, harvesting will be late and in drier conditions, resulting in less potential yields.[146]

Mitigation and adaptation

In developed countries

Several mitigation measures for use in developed countries have been proposed: [147]

- breeding more resilient crop varieties, and diversification of crop species

- using improved agroforestry species

- capture and retention of rainfall, and use of improved irrigation practices

- Increasing forest cover and Agroforestry

- use of emerging water harvesting techniques (such as contour trenching, ...)

In developing countries

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has reported that agriculture is responsible for over a quarter of total global greenhouse gas emissions.[148] Given that agriculture's share in global gross domestic product (GDP) is about 4%, these figures suggest that agriculture is highly greenhouse gas intensive. Innovative agricultural practices and technologies can play a role in climate change mitigation[149] and adaptation. This adaptation and mitigation potential is nowhere more pronounced than in developing countries where agricultural productivity remains low; poverty, vulnerability and food insecurity remain high; and the direct effects of climate change are expected to be especially harsh. Creating the necessary agricultural technologies and harnessing them to enable developing countries to adapt their agricultural systems to changing climate will require innovations in policy and institutions as well. In this context, institutions and policies are important at multiple scales.

Travis Lybbert and Daniel Sumner suggest six policy principles:[150]

- The best policy and institutional responses will enhance information flows, incentives and flexibility.

- Policies and institutions that promote economic development and reduce poverty will often improve agricultural adaptation and may also pave the way for more effective climate change mitigation through agriculture.

- Business as usual among the world's poor is not adequate.

- Existing technology options must be made more available and accessible without overlooking complementary capacity and investments.

- Adaptation and mitigation in agriculture will require local responses, but effective policy responses must also reflect global impacts and inter-linkages.

- Trade will play a critical role in both mitigation and adaptation, but will itself be shaped importantly by climate change.

The Agricultural Model Intercomparison and Improvement Project (AgMIP)[151] was developed in 2010 to evaluate agricultural models and intercompare their ability to predict climate impacts. In sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, South America and East Asia, AgMIP regional research teams (RRTs) are conducting integrated assessments to improve understanding of agricultural impacts of climate change (including biophysical and economic impacts) at national and regional scales. Other AgMIP initiatives include global gridded modeling, data and information technology (IT) tool development, simulation of crop pests and diseases, site-based crop-climate sensitivity studies, and aggregation and scaling.

One of the most important projects to mitigate climate change with agriculture and adapting agriculture to climate change at the same time, was launched in 2019 by the "Global EverGreening Alliance". The initiative was announced in the 2019 UN Climate Action Summit. One of the main methods is Agroforestry. Another important method is Conservation farming. One of the targets is to sequester carbon from the atmosphere. By 2050 the restored land should sequestrate 20 billion of carbon annually. The coalition wants, among other, to recover with trees a territory of 5.75 million square kilometres, achieve a health tree - grass balance on a territory of 6.5 million square kilometres and increase carbon capture in a territory of 5 million square kilometres.

The first phase is the "Grand African Savannah Green Up" project. Already millions families implemented these methods, and the average territory covered with trees in the farms in Sahel increased to 16%.[152]

Impact of agriculture on climate change

The agricultural sector is a driving force in the gas emissions and land use effects thought to cause climate change. In addition to being a significant user of land and consumer of fossil fuel, agriculture contributes directly to greenhouse gas emissions through practices such as rice production and the raising of livestock;[153] according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the three main causes of the increase in greenhouse gases observed over the past 250 years have been fossil fuels, land use, and agriculture.[154]

Land use

Agriculture contributes to greenhouse gas increases through land use in four main ways:

- CO2 releases linked to deforestation

- Methane releases from rice cultivation

- Methane releases from enteric fermentation in cattle

- Nitrous oxide releases from fertilizer application

Together, these agricultural processes comprise 54% of methane emissions, roughly 80% of nitrous oxide emissions, and virtually all carbon dioxide emissions tied to land use.[155]

The planet's major changes to land cover since 1750 have resulted from deforestation in temperate regions: when forests and woodlands are cleared to make room for fields and pastures, the albedo of the affected area increases, which can result in either warming or cooling effects, depending on local conditions.[156] Deforestation also affects regional carbon reuptake, which can result in increased concentrations of CO2, the dominant greenhouse gas.[157] Land-clearing methods such as slash and burn compound these effects by burning biomatter, which directly releases greenhouse gases and particulate matter such as soot into the air.

Livestock

Livestock and livestock-related activities such as deforestation and increasingly fuel-intensive farming practices are responsible for over 18%[158] of human-made greenhouse gas emissions, including:

- 9% of global carbon dioxide emissions

- 35–40% of global methane emissions (chiefly due to enteric fermentation and manure)

- 64% of global nitrous oxide emissions (chiefly due to fertilizer use.[158])

Livestock activities also contribute disproportionately to land-use effects, since crops such as corn and alfalfa are cultivated in order to feed the animals.

In 2010, enteric fermentation accounted for 43% of the total greenhouse gas emissions from all agricultural activity in the world.[159] The meat from ruminants has a higher carbon equivalent footprint than other meats or vegetarian sources of protein based on a global meta-analysis of lifecycle assessment studies.[160] Methane production by animals, principally ruminants, is estimated 15-20% global production of methane.[161][162]

Worldwide, livestock production occupies 70% of all land used for agriculture, or 30% of the land surface of the Earth.[158] The way livestock is grazed also decides the fertility of the land in the future, not circulating grazing can lead to unhealthy soil and the expansion of livestock farms affects the habitats of local animals and has led to the drop in population of many local species from being displaced.

See also

- Agroecology

- Aridification

- Biochar

- Climate change and invasive species

- Climate change and meat production

- Climate resilience

- Environmental issues with agriculture

- Fisheries and Climate Change

- Food security

- Global warming and wine

- International Assessment of Agricultural Science and Technology for Development addressing the links between climate change & agriculture

- Land Allocation Decision Support System – a research tool that is used to test how climate change may affect agriculture (e.g. yield and quality)

- Malthusian catastrophe

- Retreat of glaciers since 1850

- Slash-and-char

- Terra preta

- Water crisis

References

- Milius S (13 December 2017). "Worries grow that climate change will quietly steal nutrients from major food crops". Science News. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Hoffmann, U., Section B: Agriculture - a key driver and a major victim of global warming, in: Lead Article, in: Chapter 1, in Hoffmann 2013, pp. 3, 5

- Porter, J.R., et al., Executive summary, in: Chapter 7: Food security and food production systems (archived 5 November 2014), in IPCC AR5 WG2 A 2014, pp. 488–489

- Section 4.2: Agriculture’s current contribution to greenhouse gas emissions, in: HLPE 2012, pp. 67–69

- Sarkodie, Samuel A.; Ntiamoah, Evans B.; Li, Dongmei (2019). "Panel heterogeneous distribution analysis of trade and modernized agriculture on CO2 emissions: The role of renewable and fossil fuel energy consumption". Natural Resources Forum. 43 (3): 135–153. doi:10.1111/1477-8947.12183. ISSN 1477-8947.

- Blanco, G., et al., Section 5.3.5.4: Agriculture, Forestry, Other Land Use, in: Chapter 5: Drivers, Trends and Mitigation (archived 30 December 2014), in: IPCC AR5 WG3 2014, p. 383 Emissions aggregated using 100-year global warming potentials from the IPCC Second Assessment Report

- Science Advice for Policy by European Academies (2020). A sustainable food system for the European Union (PDF). Berlin: SAPEA. p. 39. doi:10.26356/sustainablefood. ISBN 978-3-9820301-7-3.

- Porter, J.R., et al., Section 7.5: Adaptation and Managing Risks in Agriculture and Other Food System Activities, in Chapter 7: Food security and food production systems (archived 5 November 2014), in IPCC AR5 WG2 A 2014, pp. 513–520

- Oppenheimer, M., et al., Section 19.7. Assessment of Response Strategies to Manage Risks, in: Chapter 19: Emergent risks and key vulnerabilities (archived 5 November 2014), in IPCC AR5 WG2 A 2014, p. 1080

- SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS, in: HLPE 2012, pp. 12–23

- Current climate change policies are described in Annex I NC 2014 and Non-Annex I NC 2014

- Smith, P., et al., Executive summary, in: Chapter 5: Drivers, Trends and Mitigation (archived 30 December 2014), in: IPCC AR5 WG3 2014, pp. 816–817

-

- "Climate 'could devastate crops'". BBC News. 31 January 2008.

- Lobell & others 2008a.

- Smith, K.R.; Woodward, A.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Chadee, D.D.; Honda, Y.; Liu, Q.; Olwoch, J.M.; Revich, B.; Sauerborn, R. "Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Chapter11: : Human health: impacts, adaptation, and co-benefits. Section: 11.8.2 (Limits to Food Production and Human Nutrition). Page 736" (PDF). Intergovermental Pannel On Climate Change. Intergovermental Pannel On Climate Change. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Little, Amanda (28 August 2019). "Climate Change Is Likely to Devastate the Global Food Supply. But There's Still Reason to Be Hopeful". Time. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- Rosane, Olivia (10 December 2019). "Study Finds 'Underexplored Vulnerability in the Food System': Jet Stream-Fueled Global Heat Waves". Ecowatch. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- Fraser, E (2007a). "Travelling in antique lands: Studying past famines to understand present vulnerabilities to climate change". Climate Change. 83 (4): 495–514. Bibcode:2007ClCh...83..495F. doi:10.1007/s10584-007-9240-9.

- Simelton E, Fraser E, Termansen M (2009). "Typologies of crop-drought vulnerability: an empirical analysis of the socio-economic factors that influence the sensitivity and resilience to drought of three major food crops in China (1961–2001)". Environmental Science & Policy. 12 (4): 438–452. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2008.11.005.

- Fraser ED, Termansen M, Sun N, Guan D, Simelton E, Dodds P, Feng K, Yu Y (2008). "Quantifying socio economic characteristics of drought sensitive regions: evidence from Chinese provincial agricultural data". Comptes Rendus Geoscience. 340 (9–10): 679–688. Bibcode:2008CRGeo.340..679F. doi:10.1016/j.crte.2008.07.004.

- Fraser ED, Simelton E, Termansen M, Gosling SN, South A (2013). "'Vulnerability hotspots': integrating socio-economic and hydrological models to identify where cereal production may decline due to climate change induced drought". Agricultural and Forest Meteorology. 170: 195–205. Bibcode:2013AgFM..170..195F. doi:10.1016/j.agrformet.2012.04.008.

- Harding AE, Rivington M, Mineter MJ, Tett SF (2015). "Agro-meteorological indices and climate model uncertainty over the UK". Climatic Change. 128 (1): 113–126. Bibcode:2015ClCh..128..113H. doi:10.1007/s10584-014-1296-8.

- Monier E, Xu L, Snyder R (2016). "Uncertainty in future agro-climate projections in the United States and benefits of greenhouse gas mitigation". Environmental Research Letters. 11 (5): 055001. Bibcode:2016ERL....11e5001M. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/11/5/055001.

- "Global Warming Could Trigger Insect Population Boom". Live Science. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- Stange E (November 2010). "Climate Change Impact: Insects". Norwegian Institute for Nature Research.

- "Crops, Beetles, and Carbon Dioxide". Union of Concerned Scientists. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- "Agricultural Adaptation to Climate Change". Archived from the original on 4 May 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- Stange E (November 2010). "Climate Change Impact: Insects". Norwegian Institute for Nature Research.

- Coakley SM, Scherm H, Chakraborty S (September 1999). "Climate change and plant disease management". Annual Review of Phytopathology. 37: 399–426. doi:10.1146/annurev.phyto.37.1.399. PMID 11701829.

- Rosenzweig C (2007). "Executive summary". In Parry MC, et al. (eds.). Chapter 1: Assessment of Observed Changes and Responses in Natural and Managed Systems. Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: contribution of Working Group II to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, UK: Print version: CUP. This version: IPCC website. ISBN 978-0-521-88010-7. Archived from the original on 2 November 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- Rosenzweig C (2007). "1.3.6.1 Crops and livestock". In Parry ML, et al. (eds.). Chapter 1: Assessment of Observed Changes and Responses in Natural and Managed Systems. Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: contribution of Working Group II to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, UK: Print version: CUP. This version: IPCC website. ISBN 978-0-521-88010-7. Archived from the original on 3 November 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- Parry ML, et al., eds. (2007). "Definition of "phenology"". Appendix I: Glossary. Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: contribution of Working Group II to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, UK: Print version: CUP. This version: IPCC website. ISBN 978-0-521-88010-7. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- Dai, A. (2011). "Drought under global warming: A review". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. 2: 45–65. Bibcode:2011AGUFM.H42G..01D. doi:10.1002/wcc.81.

- Mishra AK, Singh VP (2011). "Drought modeling – A review". Journal of Hydrology. 403 (1–2): 157–175. Bibcode:2011JHyd..403..157M. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2011.03.049.

- Ding Y, Hayes MJ, Widhalm M (2011). "Measuring economic impacts of drought: A review and discussion". Disaster Prevention and Management. 20 (4): 434–446. doi:10.1108/09653561111161752.

- institutt, NRK og Meteorologisk. "Weather statistics for Jalgaon". yr.no. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- Damodaran, Harish. "The story of Jalgaon district in Maharashtra as the 'new' banana republic". Indian Express.

- "Climate Change Knowledge Portal 2.0". World Bank. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- "FAOSTAT Agricultural production". Food and Agriculture Association of the United Nations. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011.

- "Crop production". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- BERWYN, BOB (28 July 1018). "This Summer's Heat Waves Could Be the Strongest Climate Signal Yet" (Climate change). Inside Climate News. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- Climate Change and Land report

- Climate Change Threatens the World’s Food Supply, United Nations Warns

- Vidal J, Stewart H. "Heatwave devastates Europe's crops" (Climate Change). The Guardian. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- Graziano da Silva, FAO Director-General José. "Conference Fortieth Session". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- Higgins, Eoin (29 May 2019). "Climate Crisis Brings Historic Delay to Planting Season, Pressuring Farmers and Food Prices". Ecowatch. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Schneider SH (2007). "19.3.1 Introduction to Table 19.1". In Parry ML, et al. (eds.). Chapter 19: Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and the Risk from Climate Change. Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: contribution of Working Group II to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, UK: Print version: CUP. This version: IPCC website. ISBN 978-0-521-88010-7. Archived from the original on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- Parry ML (2007). "Box TS.2. Communication of uncertainty in the Working Group II Fourth Assessment". In Parry ML, et al. (eds.). Technical summary. Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: contribution of Working Group II to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, UK: Print version: CUP. This version: IPCC website. ISBN 978-0-521-88010-7. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- Schneider SH (2007). "19.3.2.1 Agriculture". In Parry ML, et al. (eds.). Chapter 19: Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and the Risk from Climate Change. Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: contribution of Working Group II to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, UK: Print version: CUP. This version: IPCC website. p. 790. ISBN 978-0-521-88010-7. Archived from the original on 19 August 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- Figure 5.1, p.161, in: Sec 5.1 FOOD PRODUCTION, PRICES, AND HUNGER, in: Ch 5: Impacts in the Next Few Decades and Coming Centuries, in: US NRC 2011

- Sec 5.1 FOOD PRODUCTION, PRICES, AND HUNGER, pp.160-162, in: Ch 5: Impacts in the Next Few Decades and Coming Centuries, in US NRC 2011

- Challinor, A. J.; Watson, J.; Lobell, D. B.; Howden, S. M.; Smith, D. R.; Chhetri, N. (2014). "A meta-analysis of crop yield under climate change and adaptation" (PDF). Nature Climate Change. 4 (4): 287–291. doi:10.1038/nclimate2153. ISSN 1758-678X.

- Smith MR, Myers SS (27 August 2018). "Impact of anthropogenic CO2 emissions on global human nutrition". Nature Climate Change. 8 (9): 834–839. Bibcode:2018NatCC...8..834S. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0253-3. ISSN 1758-678X.

- Davis N (27 August 2018). "Climate change will make hundreds of millions more people nutrient deficient". the Guardian. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- Loladze I (7 May 2014). "Hidden shift of the ionome of plants exposed to elevated CO2 depletes minerals at the base of human nutrition". eLife. 3 (9): e02245. doi:10.7554/eLife.02245. PMC 4034684. PMID 24867639.

- Easterling WE (2007). "5.6.5 Food security and vulnerability". In Parry ML, et al. (eds.). Chapter 5: Food, Fibre, and Forest Products. Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: contribution of Working Group II to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88010-7. Archived from the original on 2 November 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- Easterling WE (2007). "Executive summary". In Parry ML, et al. (eds.). Chapter 5: Food, Fibre, and Forest Products. Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: contribution of Working Group II to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88010-7.

- "World hunger increasing". Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) Newsroom. 30 October 2006. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- Howden, M. e. (2007). Adapting Agriculture to Climate Change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104/50, 19691-19696

- Cline 2008

- Lobell & others 2008a (paywall). Lobell & others 2008b can be freely accessed.

- Battisti & Naylor 2009

- Ending hunger will require trade policy reform, Press Release, International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development, 12 October 2009.

- Climate change, agriculture and aid for trade, by Jodie Keane, ICTSD-IPC

- OECD/FAO (2016). OECD‑FAO Agricultural Outlook 2016‑2025 (PDF). OECD Publishing. pp. 59–61. ISBN 978-92-64-25323-0.

- IPCC (2007). "Summary for Policymakers: C. Current knowledge about future impacts". In Parry ML, et al. (eds.). Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press.

- Dhanush D, Bett BK, Boone RB, Grace D, Kinyangi J, Lindahl JF, Mohan CV, Ramírez Villegas J, Robinson TP, Rosenstock TS, Smith J (2015). "Impact of climate change on African agriculture: focus on pests and diseases". CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS).

- "SOFI 2019 - The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World". www.fao.org. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- "East African agriculture and climate change: A comprehensive analysis". International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- Kurukulasuriya P, Mendelsohn R (25 September 2008). How Will Climate Change Shift Agro-Ecological Zones And Impact African Agriculture?. Policy Research Working Papers. The World Bank. doi:10.1596/1813-9450-4717. hdl:10986/6994.

- "Future Climate For Africa". Brief: future climate projections for Tanzania. Future Climate For Africa. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- Vidal J (30 June 2005). "In the land where life is on hold". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- https://www.climatelinks.org/sites/default/files/asset/document/2016%20CRM%20Fact%20Sheet%20-%20Southern%20Africa.pdf

- "Overview [in Southern African Agriculture and Climate Change]". www.ifpri.org. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- http://cdm15738.contentdm.oclc.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/127787/filename/127998.pdf

- Rosane, Oivia (9 December 2019). "Victoria Falls Dries Drastically After Worst Drought in a Century". Ecowatch. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20090027893.pdf

- http://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/127449/filename/127660.pdf

- "Fall Armyworm | FOOD CHAIN CRISIS | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations". www.fao.org. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- Asenso-Okyere WK, Benneh G, Tims W, eds. (1997). Sustainable Food Security in West Africa. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-6105-7. ISBN 978-1-4613-7797-9.

- "CLIMATE RISKS IN THE CENTRAL AFRICA REGIONAL PROGRAM FOR THE ENVIRONMENT (CARPE) AND CONGO BASIN". Climatelinks.

- "Agriculture in Africa" (PDF). United Nations. 2013.

- Singh SK (2016). "Climate Change: Impact on Indian Agriculture & its Mitigation". Journal of Basic and Applied Engineering Research. 3 (10): 857–859.

- Rao P, Patil Y (2017). Reconsidering the Impact of Climate Change on Global Water Supply, Use, and Management. IGI Global. p. 330. ISBN 978-1-5225-1047-5.

- Vulnerability to Climate Change: Adaptation Strategies and layers of Resilience, ICRISAT, Policy Brief No. 23, February 2013

- Meng Q, Hou P, Lobell DB, Wang H, Cui Z, Zhang F, Chen X (2013). "The benefits of recent warming for maize production in high latitude China". Climatic Change. 122 (1–2): 341–349. doi:10.1007/s10584-013-1009-8. hdl:10.1007/s10584-013-1009-8.

- Chowdhury QM (2016). "Impact of Climate Change on Livestock in Bangladesh: A Review of What We Know and What We Need to Know" (PDF). American Journal of Agricultural Science Engineering and Technology. 3 (2): 18–25 – via e-palli.