Climate communication

Climate communication or climate change communication is a field of environmental communication and science communication focused on facilitating the communications of the effects of anthropogenic climate change. Most climate communication focuses on bringing knowledge about and potential action for responding to scientific consensus on climate change to a broader public.

_-_Climate_Lab_Book_(Ed_Hawkins).png)

The field of climate communication explores two main areas: the efficacy of existing communications strategies, and supporting the development of recommendations for improving that communication. Improving climate change communication has become the focus of several major research institutes, such as the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and Climate Outreach in the UK, as well as major international organizations, such as the IPCC and UN Climate Change Secretariat, and NGOs.

History

In her encyclopedia article in Oxford's Communications Research Encyclopedia, scholar Amy E. Chadwick describes Climate Change Communication as a new field emerging in the 1990s.[2] Early studies were connected to other environmental communications concerns such as exploring awareness and understanding of ozone depletion.[2] As of 2017, most research in this field has been conducted in the United States, Australia, Canada, and Western European countries.[2]

Major issues

Barriers to understanding

Climate communications is heavily focused on methods for inviting larger scale public action to address climate change. To this end, a lot of research focuses on barriers to public understanding and action on climate change. Scholarly evidence shows that the information deficit model of communication—where climate change communicators assume "if the public only knew more about the evidence they would act"—doesn't work. Instead, argumentation theory indicates that different audiences need different kinds of persuasive argumentation and communication. This is counter to many assumptions made by other fields such as psychology, environmental sociology, and risk communication.[3]

Additionally, climate denialism by organizations, such as The Heartland Institute in the United States,[4][5][6] and individuals introduces misinformation into public discourse and understanding.

There are several models for explaining why the public doesn't act once more informed. One of the theoretical models for this is the 5 Ds model created by Per Epsten Stoknes.[7] Stokes describes 5 major barriers to creating action from climate communication:

- Distance - many effects and impacts of climate change feel distant from individual lives

- Doom - when framed as a disaster, the message backfires, causing Eco-anxiety

- Dissonance - a disconnect between the problems (mainly the fossil fuel economy) and the things that people choose in their lives

- Denial -- psychological self defense to avoid becoming overwhelmed by fear or guilt

- iDentity -- disconnects created by social identities, such as conservative values, which are threatened by the changes that need to happen because of climate change.

In her book Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life, Kari Norgaard's study of Bygdaby—a fictional name used for a real city in Norway—found that non-response was much more complex than just a lack of information. In fact, too much information can do the exact opposite because people tend to neglect global warming once they realize there is no easy solution. When people understand the complexity of the issue, they can feel overwhelmed and helpless which can lead to apathy or skepticism.[8]

Climate literacy

Though communicating the science about climate change under the premises of an Information deficit model of communication is not very effective in creating change, comfort with and literacy in the main issues and topics of climate change is important for changing public opinion and action.[9] Several agencies and educational organizations have developed frameworks and tools for developing climate literacy, including the Climate Literacy Lab at Georgia State university,[10] and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.[11] Such resources in English have been collected by the Climate Literacy and Awareness Network.[12]

Creating change

As of 2008, most of the environmental communications evidence for effecting individual or social change were focused on behavior changes around: household energy consumption, recycling behaviours, changing transportation behavior and buying green products.[13] At that time, there were few examples of multi-level communications strategies for effecting change.[13]

Behaviour change

Since much of Climate communication is focused on engaging broad public action, much of the studies are focused on effecting behavior change. Typically, effective climate communication has three parts: cognitive, affective and place based appeals.[14]

Audience segmentation

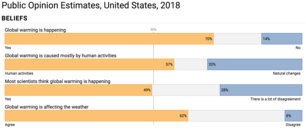

Different parts of different populations respond differently to climate change communication. Academic research since 2013 has seen an increasing number of audience segmentation studies, to understand different tactics for reaching different parts of populations.[15] Major segmentation studies include:

.svg.png)

Changing rhetoric

A significant part of the research and public advocacy conversations about climate change have focused on the effectiveness of different terms used to describe "global warming".

History of global warming

Research in the 1950s suggested that temperatures were increasing, and a 1952 newspaper used the term "climate change". This phrase next appeared in a November 1957 report in The Hammond Times which described Roger Revelle's research into the effects of increasing human-caused CO

2 emissions on the greenhouse effect: "a large scale global warming, with radical climate changes may result". A 1971 MIT report referred to the human impact as "inadvertent climate modification", identifying many possible causes. Both the terms global warming and climate change were used only occasionally until 1975, when Wallace Smith Broecker published a scientific paper on the topic, "Climatic Change: Are We on the Brink of a Pronounced Global Warming?". The phrase began to come into common use, and in 1976 Mikhail Budyko's statement that "a global warming up has started" was widely reported.[22] An influential 1979 National Academy of Sciences study headed by Jule Charney followed Broecker in using global warming to refer to rising surface temperatures, while describing the wider effects of increased CO

2 as climate change.[23]

There were increasing heatwaves and drought problems in the summer of 1988, and NASA climate scientist James Hansen's testimony in the U.S. Senate sparked worldwide interest.[24] He said, "Global warming has reached a level such that we can ascribe with a high degree of confidence a cause and effect relationship between the greenhouse effect and the observed warming."[25] Public attention increased over the summer, and global warming became the dominant popular term, commonly used both by the press and in public discourse.[23] In the 2000s, the term climate change increased in popularity.[26] The term climate change is also used to refer to past and future climate changes that persist for an extended period of time, and includes regional changes as well as global change.[27] The two terms are often used interchangeably.[28]

Various scientists, politicians and news media have adopted the terms climate crisis or a climate emergency to talk about climate change, while using global heating instead of global warming.[29] The policy editor-in-chief of The Guardian explained why they included this language in their editorial guidelines: "We want to ensure that we are being scientifically precise, while also communicating clearly with readers on this very important issue".[30] Oxford Dictionary chose climate emergency as the word of the year 2019 and defines the term as "a situation in which urgent action is required to reduce or halt climate change and avoid potentially irreversible environmental damage resulting from it".[31]Health

Climate change exacerbates a number of existing public health issues, such as mosquito-borne disease, and introduces new public health concerns related to changing climate, such as increase in health concerns after natural disasters or increases in heat illnesses. Thus the field of health communication has long acknowledged the importance of treating climate change as a public health issue, requiring broad population behavior changes that allow societal climate change adaptation.[13] A December 2008 article in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine recommended using two broad sets of tools to effect this change: communication and social marketing.[7] A 2018 study, found that even with moderates and conservatives who were skeptical of the importance of climate change, exposure to information about the health impacts of climate change creates greater conern about the issues.[32]

Media coverage

The effect of mass media and journalism on the public's attitudes towards climate change has been a significant part of communications studies. In particular, scholars have looked at how the media's tendency to cover climate change in different cultural contexts, with different audiences or political positions (for example Fox News's dismissive coverage of climate change news), and the tendency of newsrooms to cover climate change as an issue of uncertainty or debate, in order to give a sense of balance.[2]

Popular culture

Further research has explored how popular media, like the film The Day After Tomorrow and popular documentary An Inconvenient Truth change public perceptions of climate change.[2]

Effective climate communication

Effective climate communications require audience and contextual awareness. Different organizations have published guides and frameworks based on experience in climate communications. This section documents those various guidelines.

General guidance

A 2009 handbook developed by the Center for Research on Environmental Decisions at the Earth Institute at Columbia University describes eight main principles for communications based on the psychological research about Environmental decisions:[33]

- Know your audience

- Get the Audience's Attention

- Translate Scientific Data into Concrete Expereinces

- Beware the Overuse of Emotional Appeals

- Address Scientific and Climate Uncertainties

- Tap into Social Identities and Affiliates

- Encourage Group Participation

- Make Behavior Change Easier

By experts

In 2018, the IPCC published a handbook of guidance for IPCC authors about effective climate communication. It is based on extensive social studies research exploring the impact of different tactics for climate communication.[34] The guidelines focus on six main principles:

- Be a confident communicator

- Talk about the real world, not abstract ideas

- Connect with what matters to your audience

- Tell a human story

- Lead with what you know

- Use the most effective visual communication

Visuals

Climate Visuals a nonprofit, published in 2020 a set of guidelines based on evidence for climate communications.[35] They recommend that visual communications include:

- Show real people

- Tell new stories

- Show climate change causes at scale

- Show emotionally powerful impacts

- Understand your audience

- Show local (serious) impacts

- Be careful with protest imagery.

Sustainable development

The impacts of climate change are exacerbated in low- and middle income countries; higher levels of poverty, less access to technologies, and less education, means that this audience needs different information. The Paris Agreement and IPCC both acknowledge the importance of sustainable development in addressing these differences. In 2019 nonprofit, Climate and Development Knowledge Network published a set of lessons learned and guidelines based on their experience communicating climate change in Latin America, Asia and Africa.[36]

Important organizations

Major research centers in climate communication include:

- Yale Program on Climate Change Communication

- Center for Climate Change Communication at George Mason University

References

- Hawkins, Ed (4 December 2018). "2018 visualisation update / Warming stripes for 1850-2018 using the WMO annual global temperature dataset". Climate Lab Book. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. (Direct link to image)

- Chadwick, Amy E. (2017-09-26). "Climate Change Communication". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.22. ISBN 9780190228613. Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- Norgaard, K. M. (2011). Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262015448.

- Dryzek, John S.; Norgaard, Richard B.; Schlosberg, David (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199683420.

- Pilkey Jr., Orrin H; Pilkey, Keith C. (2011). Global Climate Change: A Primer. Duke University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0822351092.

- Gillis, Justin (May 1, 2012). "Clouds' Effect on Climate Change Is Last Bastion for Dissenters". The New York Times. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

...the Heartland Institute, the primary American organization pushing climate change skepticism...

- Stoknes, Per Espen (2015-04-03). "The 5 psychological barriers to climate action". Boing Boing. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- Norgaard, Kari Marie (2011), Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life, The MIT Press, doi:10.7551/mitpress/8661.003.0003, ISBN 9780262295772

- "Mind the Climate Literacy Gap". Resilience. 2019-11-01. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- "What is Climate Literacy? |". sites.gsu.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- "The Essential Principles of Climate Literacy | NOAA Climate.gov". www.climate.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- "CLEAN". CLEAN. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- Maibach, Edward W.; Roser-Renouf, Connie; Leiserowitz, Anthony (November 2008). "Communication and Marketing As Climate Change–Intervention Assets". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 35 (5): 488–500. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.016. PMID 18929975.

- Halperin, Abby; Walton, Peter (April 2018). "The Importance of Place in Communicating Climate Change to Different Facets of the American Public". Weather, Climate, and Society. 10 (2): 291–305. doi:10.1175/WCAS-D-16-0119.1. ISSN 1948-8327.

- Hine, Donald W; Reser, Joseph P; Morrison, Mark; Phillips, Wendy J; Nunn, Patrick; Cooksey, Ray (July 2014). "Audience segmentation and climate change communication: conceptual and methodological considerations: Audience segmentation and climate change communication". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. 5 (4): 441–459. doi:10.1002/wcc.279.

- Chryst, Breanne; Marlon, Jennifer; van der Linden, Sander; Leiserowitz, Anthony; Maibach, Edward; Roser-Renouf, Connie (2018-11-17). "Global Warming's "Six Americas Short Survey": Audience Segmentation of Climate Change Views Using a Four Question Instrument". Environmental Communication. 12 (8): 1109–1122. doi:10.1080/17524032.2018.1508047. ISSN 1752-4032.

- Ashworth, Peta; Jeanneret, Talia; Gardner, John; Shaw, Hylton (May 2011). Communication and climate change: What the Australian public thinks (Report). Pullenvale: CSIRO. doi:10.4225/08/584ee953cdee1.

- Morrison, M.; Duncan, R.; Sherley, C.; Parton, K. (June 2013). "A comparison between attitudes to climate change in Australia and the United States". Australasian Journal of Environmental Management. 20 (2): 87–100. doi:10.1080/14486563.2012.762946. ISSN 1448-6563.

- Metag, Julia; Füchslin, Tobias; Schäfer, Mike S. (May 2017). "Global warming's five Germanys: A typology of Germans' views on climate change and patterns of media use and information" (PDF). Public Understanding of Science. 26 (4): 434–451. doi:10.1177/0963662515592558. ISSN 0963-6625. PMID 26142148.

- "Global Warming's Six Indias". Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- Schmoldt, A.; Benthe, H. F.; Haberland, G. (1975-09-01). "Digitoxin metabolism by rat liver microsomes". Biochemical Pharmacology. 24 (17): 1639–1641. ISSN 1873-2968. PMID 10.

- Weart "Suspicions of a Human-Caused Greenhouse (1956–1969)". See also footnote 27.

- NASA, 5 December 2008.

- Weart "The Public and Climate Change: The Summer of 1988", "News reporters gave only a little attention....".

- U.S. Senate, Hearings 1988, p. 44.

- Joo et al. 2015.

- NOAA, 17 June 2015; IPCC AR5 SYR Glossary 2014, p. 120: "Climate change refers to a change in the state of the climate that can be identified (e.g., by using statistical tests) by changes in the mean and/or the variability of its properties and that persists for an extended period, typically decades or longer. Climate change may be due to natural internal processes or external forcings such as modulations of the solar cycles, volcanic eruptions and persistent anthropogenic changes in the composition of the atmosphere or in land use."

- Shaftel 2016: " 'Climate change' and 'global warming' are often used interchangeably but have distinct meanings. .... Global warming refers to the upward temperature trend across the entire Earth since the early 20th century .... Climate change refers to a broad range of global phenomena ...[which] include the increased temperature trends described by global warming."

- Hodder & Martin 2009; BBC Science Focus Magazine, 3 February 2020.

- The Guardian, 17 May 2019; BBC Science Focus Magazine, 3 February 2020.

- USA Today, 21 November 2019.

- Kotcher, John; Maibach, Edward; Montoro, Marybeth; Hassol, Susan Joy (September 2018). "How Americans Respond to Information About Global Warming's Health Impacts: Evidence From a National Survey Experiment". GeoHealth. 2 (9): 262–275. doi:10.1029/2018GH000154. PMC 7007167. PMID 32159018.

- The Psychology of Climate Change Communication: A Guide for Scientists, Journalists, Educators, Political Aides, and the Interested Public. Center For Research on Environmental Decisions, Columbia University. 2009.

- "Communications Handbook for IPCC scientists". Climate Outreach. January 30, 2018. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- "The evidence behind Climate Visuals". Climate Visuals. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- "GUIDE: Communicating climate change - A practitioner's guide". Climate and Development Knowledge Network. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

Bibliography

- Carrington, Damian (17 May 2019). "Why the Guardian is changing the language it uses about the environment". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- Conway, Erik M. (5 December 2008). "What's in a Name? Global Warming vs. Climate Change". NASA. Archived from the original on 9 August 2010.

- IPCC (2014). "Annex II: Glossary" (PDF). IPCC AR5 SYR.

- Hodder, Patrick; Martin, Brian (2009). "Climate Crisis? The Politics of Emergency Framing". Economic and Political Weekly. 44 (36): 53–60. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 25663518.

- Joo, Gea-Jae; Kim, Ji Yoon; Do, Yuno; Lineman, Maurice (2015). "Talking about Climate Change and Global Warming". PLOS ONE. 10 (9): e0138996. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1038996L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138996. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4587979. PMID 26418127.

- Rice, Doyle (21 November 2019). "'Climate emergency' is Oxford Dictionary's word of the year". USA TODAY. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Rigby, Sara (3 February 2020). "Climate change: should we change the terminology?". BBC Science Focus Magazine. Retrieved 2020-03-24.

- Shaftel, Holly (January 2016). "What's in a name? Weather, global warming and climate change". NASA Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet. Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- Weart, Spencer R. (February 2014a). "The Public and Climate Change: Suspicions of a Human-Caused Greenhouse (1956–1969)". The Discovery of Global Warming. American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- Weart, Spencer R. (February 2014b). "The Public and Climate Change: The Summer of 1988". The Discovery of Global Warming. American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- "What's the difference between global warming and climate change?". NOAA Climate.gov. 17 June 2015. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- U.S. Senate, Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, 100th Cong. 1st sess. (23 June 1988). Greenhouse Effect and Global Climate Change: hearing before the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, part 2.