Lotus Sutra

The Lotus Sūtra (Sanskrit: Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtra, lit. 'Sūtra on the White Lotus of the Sublime Dharma')[1] is one of the most popular and influential Mahayana sutras, and the basis on which the Tiantai, Tendai, Cheontae, and Nichiren schools of Buddhism were established.

| Part of a series on |

| Mahāyāna Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Transmission |

|

Teachings

|

|

Mahāyāna sūtras |

According to British professor Paul Williams, "For many East Asian Buddhists since early times, the Lotus Sutra contains the final teaching of the Buddha, complete and sufficient for salvation."[2]

Title

The earliest known Sanskrit title for the sūtra is the सद्धर्मपुण्डरीक सूत्र, Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtra, meaning 'Scripture of the Lotus Blossom of the Fine Dharma'.[3] In English, the shortened form Lotus Sūtra is common. The Lotus Sūtra has also been highly regarded in a number of Asian countries where Mahāyāna Buddhism has been traditionally practiced.

Translations of this title into the languages of some of these countries include:[note 1]

- Chinese: 妙法蓮華經; pinyin: Miàofǎ Liánhuá jīng (shortened to 法華經; Fǎhuá jīng).

- Japanese: 妙法蓮華経, Myōhō Renge Kyō (short: 法華経, Hokke-kyō, Hoke-kyō).

- Korean: 묘법연화경; RR: Myobeop Yeonhwa gyeong (short: Beophwa gyeong).

- Tibetan: དམ་ཆོས་པད་མ་དཀར་པོའི་མདོ, Wylie: dam chos padma dkar po'i mdo, THL: Damchö Pema Karpo'i do

- Vietnamese: Diệu pháp Liên hoa kinh (short: Pháp hoa kinh).

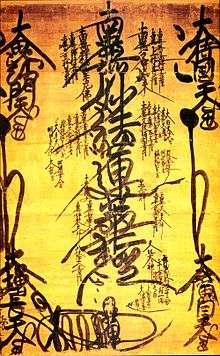

Nichiren (1222-1282) regarded the title as the summary of the Lotus Sutra´s teachings. The chanting of the title as a mantra is the basic religious practice of his school.[4][5]

Textual history

Formation

In 1934, based on his text-critical analysis of Chinese and Sanskrit versions, Kogaku Fuse concluded that the Lotus Sūtra was composed in four main stages. According to Fuse, the verse sections of chapters 1-9 and 17 were probably created in the 1st century BCE, with the prose sections of these chapters added in the 1st century CE. He estimates the date of the 3rd stage (ch. 10, 11, 13-16, 18-20 and 27) to be around 100 CE, and the last stage (ch. 21-26), around 150 CE.[6][note 2]

According to Stephen F. Teiser and Jacqueline Stone, there is consensus about the stages of composition but not about the dating of these strata.[8]

Tamura argues that the first stage of composition (ch. 2-9) was completed around 50 CE and expanded by chapters 10-21 around 100 CE. He dates the third stage (ch. 22-27) around 150 CE.[9]

Karashima proposes another modified version of Fuse's hypothesis with the following sequence of composition:[10][11]

Translations into Chinese

Three translations of the Lotus Sūtra into Chinese are extant.[15][16][17][note 4]

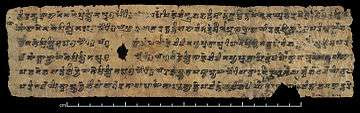

The Lotus Sūtra was originally translated from Sanskrit into Chinese by Dharmarakṣa´s team in 286 CE in Chang'an during the Western Jin Period (265-317 CE).[19][20][note 5] However, the view that there is a high degree of probability that the base text for that translation was actually written in a Prakrit language has gained widespread acceptance.[note 6] It may have originally been composed in a Prakrit dialect and then later translated into Sanskrit to lend it greater respectability.[22]

This early translation by Dharmarakṣa was superseded by a translation in seven fascicles by Kumārajīva´s team in 406 CE.[23][24][25][note 7] According to Jean-Noël Robert, Kumārajīva relied heavily on the earlier version.[26] The Sanskrit editions[27][28][29][30] are not widely used outside of academia.

The Supplemented Lotus Sūtra of the Wonderful Dharma (Tiān Pǐn Miàofǎ Liánhuá Jīng), in 7 volumes and 27 chapters, is a revised version of Kumarajiva's text, translated by Jnanagupta and Dharmagupta in 601 CE.[31]

In some East Asian traditions, the Lotus Sūtra has been compiled together with two other sutras which serve as a prologue and epilogue:

- the Innumerable Meanings Sutra (Chinese: 無量義經; pinyin: Wúliángyì jīng; Japanese: Muryōgi kyō);[32] and

- the Samantabhadra Meditation Sutra (Chinese: 普賢經; pinyin: Pǔxián jīng; Japanese: Fugen kyō).[33][34] This composite sutra is often called the Threefold Lotus Sūtra or Three-Part Dharma Flower Sutra (Chinese: 法華三部経; pinyin: Fǎhuá Sānbù jīng; Japanese: Hokke Sambu kyō).[35]

Translations into Western languages

Eugene Burnouf's Introduction à l'histoire du Buddhisme indien (1844) marks the start of modern academic scholarship of Buddhism in the West. His translation of a Nepalese Sanskrit manuscript of the Lotus Sutra, "Le Lotus de la bonne loi", was published posthumously in 1852.[36][37] Prior to publication, a chapter from the translation was included in the 1844 journal The Dial, a publication of the New England transcendentalists, translated from French to English by Elizabeth Palmer Peabody.[38] A translation of the Lotus Sutra from an ancient Sanskrit manuscript was completed by Hendrik Kern in 1884.[39][40][41]

Western interest in the Lotus Sutra waned in the latter 19th century as Indo-centric scholars focused on older Pali and Sanskrit texts. However, Christian missionaries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, based predominantly in China, became interested in Kumārajīva's translation of the Lotus Sutra into Chinese. These scholars attempted to draw parallels between the Old and New Testaments to earlier Nikaya sutras and the Lotus Sutra. Abbreviated and "christo-centric" translations were published by Richard and Soothill.[42][43]

In the post World War II years, scholarly attention to the Lotus Sutra was inspired by renewed interest in Japanese Buddhism as well as archeological research in Dunhuang. This led to the 1976 Leon Hurvitz publication of the Lotus Sutra based on Kumarajiva's translation. Whereas the Hurvitz work was independent scholarship, other modern translations were sponsored by Buddhist groups: Kato Bunno (1975, Nichiren-shu/Rissho-kosei-kai), Murano Senchu (1974, Nichiren-shu), Burton Watson (1993, Soka Gakkai), and the Buddhist Text Translation Society (Xuanhua).[44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51] The translations into French,[52] Spanish[53] and German[54][55] are based on Kumarajiva's Chinese text. Each of these translations incorporate different approaches and styles that range from complex to simplified.[56]

Outline

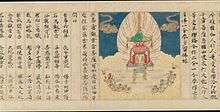

The sutra is presented in the form of a drama consisting of several scenes.[57] According to Sangharakshita, it uses the entire cosmos for its stage, employs a multitude of mythological beings as actors and "speaks almost exclusively in the language of images."[58]

The Lotus Sutra can be divided into two parts:

- Chapters 1–14 are called the Theoretical Teachings (Japanese: Shakumon).

- Chapters 15–28 are referred to as the Essential Teachings (Japanese: Honmon).

The difference between the two lies with the standpoint of who is preaching them. The Theoretical Teachings (ch. 1–14) are preached from the standpoint of Shakyamuni Buddha, who attained Buddhahood for the first time at the City of Gaya in India. On the other hand, Shakyamuni declares in the Essential Teachings (ch. 15–28) that his enlightenment in India was provisional, and that he in fact attained Buddhahood in the inconceivably remote past. As result of this (based on the interpretations of the Tiantai/Tendai school and Nichiren Daishonin), all the provisional Buddhas, such as Amida Nyorai, Dainichi Nyorai, and Yakushi Nyorai, were integrated into one single original Buddha.[59][60]

Chapter 1

Chapter 1: Introduction – During a gathering at Vulture Peak, Shakyamuni Buddha goes into a state of deep meditative absorption (samadhi), the earth shakes in six ways, and he brings forth a ray of light which illuminates thousands of buddha-fields in the east.[note 8][62][63] Bodhisattva Manjusri then states that the Buddha is about to expound his ultimate teaching.[64][65]

Chapters 2-9

Scholars suggest that chapters 2-9 contain the original form of the text. Chapter 2 explains the goals of early Buddhism, the Arhat and the Pratyekabuddha, as expedient means of teaching. The Buddha declares that there exists only one path, leading the bodhisattva to the full awakening of a Buddha. This concept is set forth in detail in chapters 3-9, using parables, narratives of previous existences and prophecies of enlightenment.[66]

Chapter 2: Expedient Means – Shakyamuni explains his use of skillful means to adapt his teachings according to the capacities of his audience.[67] He reveals that the ultimate purpose of the Buddhas is to cause sentient beings "to obtain the insight of the Buddha" and "to enter the way into the insight of the Buddha."[68][69][70]

Chapter 3: Simile and Parable – The Buddha teaches a parable in which a father uses the promise of various toy carts to get his children out of a burning house.[71] Once they are outside, he gives them all one large cart to travel in instead. This symbolizes how the Buddha uses the Three Vehicles: Arhatship, Pratyekabuddhahood and Samyaksambuddhahood, as skillful means to liberate all beings – even though there is only one vehicle.[72] The Buddha also promises Sariputra that he will attain Buddhahood.

Chapter 4: Belief and Understanding – Four senior disciples address the Buddha.[73] They tell the parable of the poor son and his rich father, who guides him with pedagogically skillful devices to regain self-confidence and "recognize his own Buddha-wisdom".[74][75]

Chapter 5: The Parable of Medicinal Herbs – This parable says that the Dharma is like a great monsoon rain that nourishes many different kinds of plants who represent Śrāvakas, Pratyekabuddhas, and Bodhisattvas,[76] and all beings receiving the teachings according to their respective capacities.[77]

Chapter 6: Bestowal of Prophecy – The Buddha prophesies the enlightenment of Mahakasyapa, Subhuti, Mahakatyayana and Mahamaudgalyayana.

Chapter 7: The Parable of Phantom City – The Buddha teaches a parable about a group of people seeking a great treasure who are tired of their journey and wish to quit. Their guide creates a magical phantom city for them to rest in and then makes it disappear.[78][79][80] The Buddha explains that the magic city represents the "Hinayana nirvana" and the treasure is buddhahood.[81]

Chapter 8: Prophecy of Enlightenment for Five Hundred Disciples – 500 Arhats are assured of their future Buddhahood. They tell the parable of a man who has fallen asleep after drinking and whose friend sews a jewel into his garment. When he wakes up he continues a life of poverty without realizing he is really rich, he only discovers the jewel after meeting his old friend again.[82][83][84][79] The hidden jewel has been interpreted as a symbol of Buddha-nature.[85] Zimmermann noted the similarity with the nine parables in the Tathāgatagarbha Sūtra that illustrate how the indwelling Buddha in sentient beings is hidden by negative mental states.[86]

Chapter 9: Prophecies Conferred on Learners and Adepts – Ananda, Rahula and two thousand Śrāvakas are assured of their future Buddhahood.[87]

Chapters 10-22

Chapters 10-22 expound the role of the bodhisattva and the concept of the eternal lifespan and omnipresence of the Buddha.[66] The theme of propagating the Lotus Sūtra which starts in chapter 10, continues in the remaining chapters.[note 9]

Chapter 10: The Teacher of the Law – Presents the practices of teaching the sutra which includes accepting, embracing, reading, reciting, copying, explaining, propagating it, and living in accordance with its teachings. The teacher of the Dharma is praised as the messenger of the Buddha.[89]

Chapter 11: The Emergence of the Treasure Tower – A great jeweled stupa rises from the earth and floats in the air;[90] a voice is heard from within praising the Lotus Sūtra.[91] Another Buddha resides in the tower, the Buddha Prabhūtaratna who is said to have made a vow to make an appearance to verify the truth of the Lotus Sutra whenever it is preached.[92] Countless manifestations of Shakyamuni Buddha in the ten directions are now summoned by the Buddha. Thereafter Prabhūtaratna invites Shakyamuni to sit beside him in the jeweled stupa.[93][94] This chapter reveals the existence of multiple Buddhas at the same time[91] and the doctrine of the eternal nature of Buddhahood.

Chapter 12: Devadatta – Through the stories of the dragon king's daughter and Devadatta, the Buddha teaches that everyone can become enlightened – women, animals, and even the most sinful murderers.[95]

Chapter 13: Encouraging Devotion – The Buddha encourages all beings to embrace the teachings of the sutra in all times, even in the most difficult ages to come. The Buddha prophecies that 6000 nuns who are also present will become Buddhas.[96]

Chapter 14: Peaceful Practices – Manjusri asks how a bodhisattva should spread the teaching. In his reply Shakyamuni Buddha describes the proper conduct and the appropriate sphere of relations of a bodhisattva.[97] A bodhisattva should not talk about the faults of other preachers or their teachings. He is encouraged to explain the Mahayana teachings when he answers questions.[98] Virtues such as patience, gentleness, a calm mind, wisdom and compassion are to be cultivated.

Chapter 15: Emerging from the Earth – In this chapter countless bodhisattvas spring up from the earth, ready to teach, and the Buddha declares that he has trained these bodhisattvas in the remote past.[99][100] This confuses some disciples including Maitreya, but the Buddha affirms that he has taught all of these bodhisattvas himself.[101]

Chapter 16: The Life Span of Thus Come One – The Buddha explains that he is truly eternal and omniscient. He then teaches the Parable of the Excellent Physician who entices his sons into taking his medicine by feigning his death.[102][103]

Chapter 17: Distinction in Benefits – The Buddha explains that since he has been teaching as many beings as the sands of the Ganges have been saved.

Chapter 18: The Benefits of Responding with Joy – Faith in the teachings of the sutra brings much merit and lead to good rebirths.

Chapter 19: Benefits of the Teacher of the Law - the Buddha praises the merits of those who teach the sutra. They will be able to purify the six senses.[104]

Chapter 20: The Bodhisattva Never Disparaging – The Buddha tells a story about a previous life when he was a Bodhisattva called sadāparibhūta ('never disparaging') and how he treated every person he met, good or bad, with respect, always remembering that they will become Buddhas.[105]

Chapter 21: Supernatural Powers of the Thus Come One – Reveals that the sutra contains all of the Eternal Buddha’s secret spiritual powers. The bodhisattvas who have sprung from the earth (ch. 15) are entrusted with the task of propagating it.[106]

Chapter 22: Entrustment – The Buddha transmits the Lotus Sutra to all bodhisattvas in his congregation and entrusts them with its safekeeping.[107][108] The Buddha Prabhūtaratna in his jeweled stupa and the countless manifestations of Shakyamuni Buddha return to their respective buddha-field.[109]

Chapters 23-28

Chapter 22: "Entrustment" – the final chapter in the Sanskrit versions and the alternative Chinese translation. Shioiri suggests that an earlier version of the sutra ended with this chapter. He assumes that the chapters 23-28 were inserted later into the Sanskrit version.[110][111] These chapters are devoted to the worship of bodhisattvas.[112][113]

Chapter 23: "Former Affairs of Bodhisattva Medicine King" – the Buddha tells the story of the 'Medicine King' Bodhisattva, who, in a previous life, burnt his body as a supreme offering to a Buddha.[114][115][116] The hearing and chanting of the Lotus Sūtra' is also said to cure diseases. The Buddha uses nine similes to declare that the Lotus Sūtra is the king of all sutras.[117]

Chapter 24: The Bodhisattva Wonderful Sound – Gadgadasvara ('Wonderful Voice'), a Bodhisattva from a distant world, visits Vulture Peak to worship the Buddha. Bodhisattva 'Wonderful Voice' once made offerings of various kinds of music to the Buddha "Cloud-Thunder-King". His accumulated merits enable him to take 34 different forms to propagate the Lotus Sutra.[118][111]

Chapter 25, The Universal Gateway of the Bodhisattva Perciever of the World's Sounds – The Bodhisattva is devoted to Avalokiteśvara, describing him as a compassionate bodhisattva who hears the cries of sentient beings, and rescues those who call upon his name.[119][120][121]

Chapter 26 – Dhāraṇī- Hariti and several Bodhisattvas offer sacred dhāraṇī ('formulae') in order to protect those who keep and recite the Lotus Sūtra.[122][123][note 10]

Chapter 27 – Former Affairs of King Wonderful Adornment - tells the story of the conversion of King 'Wonderful-Adornment' by his two sons.[125][126]

Chapter 28 – Encouragement of the Bodhisattva Universal Worthy- a bodhisattva called "Universal Virtue" asks the Buddha how to preserve the sutra in the future. Samantabhadra promises to protect and guard all those who keep this sutra in the future Age of Dharma Decline.[127]

Teachings

One vehicle, many skillful means

This Lotus Sūtra is known for its extensive instruction on the concept and usage of skillful means – (Sanskrit: upāya, Japanese: hōben), the seventh paramita or perfection of a Bodhisattva – mostly in the form of parables. The many 'skillful' or 'expedient' means and the "three vehicles" are revealed to all be part of the One Vehicle (Ekayāna), which is also the Bodhisattva path. This is also one of the first sutras to use the term Mahāyāna, or "Great Vehicle". In the Lotus Sūtra, the One Vehicle encompasses so many different teachings because the Buddha's compassion and wish to save all beings led him to adapt the teaching to suit many different kinds of people. As Paul Williams explains:[129]

Although the corpus of teachings attributed to the Buddha, if taken as a whole, embodies many contradictions, these contradictions are only apparent. Teachings are appropriate to the context in which they are given and thus their contradictions evaporate. The Buddha’s teachings are to be used like ladders, or, to apply an age-old Buddhist image, like a raft employed to cross a river. There is no point in carrying the raft once the journey has been completed and its function fulfilled. When used, such a teaching transcends itself.

The sutra emphasizes that all these seemingly different teachings are actually just skillful applications of the one Dharma and thus all constitute the "One Buddha Vehicle and knowledge of all modes". The Lotus Sūtra sees all other teachings are subservient to, propagated by and in the service of the ultimate truth of the One Vehicle leading to Buddhahood.[16] The Lotus Sūtra also claims to be superior to other sūtras and states that full Buddhahood is only arrived at by exposure to its teachings and skillful means.

All beings have the potential to become Buddhas

The One Vehicle doctrine defines the enlightenment of a Buddha (anuttara samyak sambhodi) as the ultimative goal and the sutra predicts that all those who hear the Dharma will eventually achieve this goal. Many of the Buddha´s disciples receive prophecies that they will become future Buddhas. Devadatta, who, according to the Pali texts, had attempted to kill the Buddha, receives a prediction of enlightenment.[132][133][134] Even those, who practice only simple forms of devotion, such as paying respect to the Buddha, or drawing a picture of the Buddha, are assured of their future Buddhahood.[135]

Although the term buddha-nature (buddhadhatu) is not mentioned once in the Lotus Sutra, Japanese scholars Hajime Nakamura and Akira Hirakawa suggest that the concept is implicitly present in the text.[136][137] Vasubandhu (fl. 4th to 5th century CE), an influential scholar monk from Ghandara, interpreted the Lotus Sutra as a teaching of buddha-nature and later commentaries tended to adopt this view.[138][139] Based on his analysis of chapter 5, Zhanran (711-778), a scholar monk of the Chinese Tiantai school, argued that insentient things also possess buddha-nature and in medieval Japan, the Tendai Lotus school developed its concept of original enlightenment which claimed the whole world to be originally enlighted.[140][141]

The nature of the Buddhas

Another key concept introduced by the Lotus Sūtra is the idea of the eternal Buddha, who achieved enlightenment innumerable eons ago, but remains in the world to help teach beings the Dharma time and again. The life span of this primordial Buddha is beyond imagination, his biography and his apparent death are portrayed as skillful means to teach sentient beings.[142][143] The Buddha of the Lotus Sūtra states:

In this way, since my attainment of Buddhahood it has been a very great interval of time. My life-span is incalculable asatkhyeyakalpas [rather a lot of aeons], ever enduring, never perishing. O good men! The life-span I achieved in my former treading of the bodhisattva path even now is not exhausted, for it is twice the above number. Yet even now, though in reality I am not to pass into extinction [enter final nirvana], yet I proclaim that I am about to accept extinction. By resort to these expedient devices [this skill-in-means] the Thus Come One [the Tathagata] teaches and converts the beings.[144]

The idea that the physical death of a Buddha is the termination of that Buddha is graphically refuted by the appearance of another Buddha, Prabhûtaratna, who passed long before. In the vision of the Lotus Sūtra, Buddhas are ultimately immortal.

Crucially, not only are there multiple Buddhas in this view, but an infinite stream of Buddhas extending infinitely in space in the ten directions and through unquantifiable eons of time. The Lotus Sūtra illustrates a sense of timelessness and the inconceivable, often using large numbers and measurements of time and space.

According to Gene Reeves, the Lotus Sūtra also teaches that the Buddha has many embodiments and these are the countless bodhisattva disciples. These bodhisattvas choose to remain in the world to save all beings and to keep the teaching alive. Reeves writes, "because the Buddha and his Dharma are alive in such bodhisattvas, he himself continues to be alive. The fantastically long life of the Buddha, in other words, is at least partly a function of and dependent on his being embodied in others."[145] The Lotus Sūtra also teaches various dhāraṇīs or the prayers of different celestial bodhisattvas who out of compassion protect and teach all beings. The lotus flower imagery points to this quality of the bodhisattvas. The lotus symbolizes the bodhisattva who is rooted in the earthly mud and yet flowers above the water in the open air of enlightenment.[146]

Impact

According to Donald Lopez, the Lotus Sutra is "arguably the most famous of all Buddhist texts," presenting "a radical re-vision of both the Buddhist path and of the person of the Buddha."[147][note 11]

The Lotus Sutra was frequently cited in Indian works by Nagarjuna, Vasubandhu, Candrakirti, Shantideva and several authors of the Madhyamaka and the Yogacara school.[148] The only extant Indian commentary on the Lotus Sutra is attributed to Vasubandhu.[149][150] According to Jonathan Silk, the influence of the Lotus Sūtra in India may have been limited, but "it is a prominent scripture in East Asian Buddhism."[151] The sutra has most prominence in Tiantai (sometimes called "The Lotus School"[152]) and Nichiren Buddhism.[153] It is also influential in Zen Buddhism.

China

Tao Sheng, a fifth-century Chinese Buddhist monk wrote the earliest extant commentary on the Lotus Sūtra.[154][155] Tao Sheng was known for promoting the concept of Buddha nature and the idea that even deluded people will attain enlightenment. Daoxuan (596-667) of the Tang Dynasty wrote that the Lotus Sutra was "the most important sutra in China".[156]

Zhiyi (538–597 CE), the generally credited founder of the Tiantai school of Buddhism, was the student of Nanyue Huisi[157] who was the leading authority of his time on the Lotus Sūtra.[152] Zhiyi's philosophical synthesis saw the Lotus Sūtra as the final teaching of the Buddha and the highest teaching of Buddhism.[158] He wrote two commentaries on the sutra: Profound meanings of the Lotus Sūtra and Words and phrases of the Lotus Sūtra. Zhiyi also linked the teachings of the Lotus Sūtra with the Buddha nature teachings of the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra and made a distinction between the "Eternal Buddha" Vairocana and the manifestations. In Tiantai, Vairocana (the primeval Buddha) is seen as the 'Bliss body' – Sambhogakāya – of the historical Gautama Buddha.[158]

Japan

The Lotus Sūtra is a very important sutra in Tiantai[159] and correspondingly, in Japanese Tendai (founded by Saicho, 767–822). Tendai Buddhism was the dominant form of mainstream Buddhism in Japan for many years and the influential founders of popular Japanese Buddhist sects including Nichiren, Honen, Shinran and Dogen[160] were trained as Tendai monks.

Nichiren, a 13th-century Japanese Buddhist monk, founded an entire school of Buddhism based on his belief that the Lotus Sūtra is "the Buddha´s ultimate teaching",[162] and that the title is the essence of the sutra, "the seed of Buddhahood".[163] Nichiren held that chanting the title of the Lotus Sūtra – Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō – was the only way to practice Buddhism in the degenerate age of Dharma decline and was the highest practice of Buddhism.[158] Nichiren described chapters 10-22 as the "third realm" of the Lotus Sutra (Daisan hōmon) which emphasizes the need to endure the trials of life and bodhisattva practice of the true law in the real sahā world.[164]

Dogen, the 13th-century Japanese founder of Sōtō Zen Buddhism, used the Lotus Sūtra often in his writings. According to Taigen Dan Leighton, "While Dogen's writings employ many sources, probably along with his own intuitive meditative awareness, his direct citations of the Lotus Sūtra indicate his conscious appropriation of its teachings as a significant source"[165] and that his writing "demonstrates that Dogen himself saw the Lotus Sutra, 'expounded by all buddhas in the three times,' as an important source for this self-proclamatory rhetorical style of expounding."[166] In his Shobogenzo, Dogen directly discusses the Lotus Sūtra in the essay Hokke-Ten-Hokke, "The Dharma Flower Turns the Dharma Flower". The essay uses a dialogue from the Platform Sutra between Huineng and a monk who has memorized the Lotus Sūtra to illustrate the non-dual nature of Dharma practice and sutra study.[165] During his final days, Dogen spent his time reciting and writing the Lotus Sutra in his room which he named "The Lotus Sutra Hermitage".[167]

The Soto Zen monk Ryōkan also studied the Lotus Sūtra extensively and this sutra was the biggest inspiration for his poetry and calligraphy.[168] The Rinzai Zen master Hakuin Ekaku achieved enlightenment while reading the third chapter of the Lotus Sūtra.[169]

According to Shields, "modern(ist)" interpretations of the Lotus Sutra begin with the early 20th century nationalist applications of the Lotus Sutra by Chigaku Tanaka, Nissho Honda, Seno'o, and Nisshō Inoue.[170] Japanese new religions began forming in the 19th century and the trend accelerated after World War II. Some of these groups have pushed the study of the Lotus Sutra to a global scale.[171][172] While noting the importance of several Japanese New Religious Movements to Lotus Sutra scholarship, Lopez focuses on the contributions made by the Reiyukai and Soka Gakkai[173] and Stone discusses the contributions of the Soka Gakkai and Risshō Kōsei Kai.[174] Etai Yamada (1900–1999), the 253rd head priest of the Tendai denomination conducted ecumenical dialogues with religious leaders around the world based on his interpretation of the Lotus Sutra which culminated in a 1987 summit. He also used the Lotus Sutra to move his sect from a "temple Buddhism" perspective to one based on social engagement.[175] Nichiren-inspired Buddhist organizations have shared their interpretations of the Lotus Sutra through publications, academic symposia, and exhibitions.[176][177][178][179][180]

Influence on East Asian culture

The Lotus Sūtra has had a great impact on East Asian literature, art, and folklore for over 1400 years.

Art

Various events from it are depicted in religious art.[181][182][183] Wang argues that the explosion of art inspired by the Lotus Sutra, starting from the 7th and 8th centuries in China, was a confluence of text and the topography of the Chinese medieval mind in which the latter dominated.[184]

Motifs from the Lotus Sutra figure prominently in the Dunhuang caves built in the Sui era.[185] In the fifth century, the scene of Shakyamuni and Prabhutaratna Buddhas seated together as depicted in the 11th chapter of the Lotus Sutra became arguably the most popular theme in Chinese Buddhist art.[186] Examples can be seen in a bronze plaque (year 686) at Hase-dera Temple in Japan[187] and, in Korea, at Dabotap and Seokgatap Pagodas, built in 751, at Bulguksa Temple.[188]

Literature

Tamura refers to the "Lotus Sutra literary genre."[189] Its ideas and images are writ large in great works of Chinese and Japanese literature such as The Dream of the Red Chamber and The Tale of Genji.[190] The Lotus Sutra has had an outsized influence on Japanese Buddhist poetry.[191] Far more poems have been Lotus Sutra-inspired than other sutras.[192] In the work Kanwa taisho myoho renge-kyo, a compendium of more than 120 collections of poetry from the Heian period, there are more than 1360 poems with references to the Lotus Sutra in just their titles.[193][194]

Folklore

The Lotus Sutra has inspired a branch of folklore based on figures in the sutra or subsequent people who have embraced it. The story of the Dragon King's daughter, who attained enlightenment in the 12th (Devadatta) chapter of the Lotus Sutra, appears in the Complete Tale of Avalokiteśvara and the Southern Seas and the Precious Scroll of Sudhana and Longnü folkstories. The Miraculous Tales of the Lotus Sutra[195] is a collection of 129 stories with folklore motifs based on "Buddhist pseudo-biographies."[196]

See also

- Amitabha Sutra

- Flower Sermon

- Heart Sutra

- Hokke Gisho, an annotated Japanese version of the sutra.

- Mahayana sutras

Notes

- Korean: Korean: 묘법연화경; RR: Myobeop Yeonhwa gyeong, shortened to Beophwa gyeong; Tibetan: དམ་ཆོས་པད་མ་དཀར་པོའི་མདོ, Wylie: dam chos padma dkar po'i mdo, THL: Damchö Pema Karpo'i do and Vietnamese: Diệu pháp Liên hoa kinh, shortened to Pháp hoa kinh.

- Chapter numbers of the extant Sanskrit version are given here. The arrangement and numbering of chapters in Kumarajiva's translation is different.[7]

- In the Sanskrit manuscripts chapter 5 contains the parable of a blind man who refuses to believe that vision exists.[13][14]

- Weinstein states: "Japanese scholars demonstrated decades ago that this traditional list of six translations of the Lotus lost and three surviving-given in the K'ai-yiian-lu and elsewhere is incorrect. In fact, the so-called "lost" versions never existed as separate texts; their titles were simply variants of the titles of the three "surviving" versions."[18]

- Taisho vol.9, pp. 63-134.The Lotus Sūtra of the Correct Dharma (Zhèng Fǎ Huá Jīng), in ten volumes and twenty-seven chapters, translated by Dharmarakṣa in 286 CE.

- Jan Nattier has recently summarized this aspect of the early textual transmission of such Buddhist scriptures in China thus, bearing in mind that Dharmarakṣa's period of activity falls well within the period she defines: "Studies to date indicate that Buddhist scriptures arriving in China in the early centuries of the Common Era were composed not just in one Indian dialect but in several . . . in sum, the information available to us suggests that, barring strong evidence of another kind, we should assume that any text translated in the second or third century AD was not based on Sanskrit, but one or other of the many Prakrit vernaculars."[21]

- The Lotus Sūtra of the Wonderful Dharma (Miàofǎ Liánhuá jīng), in eight volumes and twenty-eight chapters, translated by Kumārajīva in 406 CE.

- Sanskrit buddhaksetra, the realm of a Buddha, a pure land. Buswell and Lopez state that "Impure buddha-fields are synonymous with a world system (cacravada), the infinite number of “world discs” in Buddhist cosmology that constitutes the universe (...)."[61]

- Ryodo Shioiri states, "If I may speak very simply about the characteristics of section 2, chapter 10 and subsequent chapters emphasize the command to propagate the Lotus Sūtra in society as opposed to the predictions given in section 1 out (sic) the future attainment of buddhahood by the disciples....and the central concern is the actualization of the teaching-in other words, how to practice and transmit the spirit of the Lotus Sutra as contained in the original form of section 1."[88]

- Dhāraṇī is used in the "limited sense of mantra-dharani" in this chapter.[124]

- Donald Lopez: "Although composed in India, the Lotus Sutra became particularly important in China and Japan. In terms of Buddhist doctrine, it is renowned for two powerful proclamations by the Buddha. The first is that there are not three vehicles to enlightenment but one, that all beings in the universe will one day become buddhas. The second is that the Buddha did not die and pass into nirvana; in fact, his lifespan is immeasurable."[147]

References

- Shields 2013, p. 512.

- Williams 1989, p. 149.

- Hurvitz 1976.

- Buswell 2013, p. 208.

- Stone 1998, p. 138-154.

- Pye 2003, p. 177-178.

- Pye 2003, p. 173-174.

- Teiser & Stone 2009, p. 7-8.

- Kajiyama 2000, p. 73.

- Karashima 2015, p. 163.

- Apple 2012, pp. 161-162.

- Silk 2016, p. 152.

- Bingenheimer 2009, p. 72.

- Kern 1884, pp. 129-141.

- Reeves 2008, p. 2.

- The English Buddhist Dictionary Committee 2002.

- Shioiri 1989, pp. 25-26.

- Weinstein 1977, p. 90.

- Boucher 1998, pp. 285-289.

- Zürcher 2006, p. 57-69.

- Nattier 2008, p. 22.

- Watson 1993, p. IX.

- Tay 1980, pp. 374.

- Taisho vol. 9, no. 262, CBETA

- Karashima 2001, p. VII.

- Robert 2011, p. 63.

- Kern & 1908-1912.

- Vaidya 1960.

- Jamieson 2002, pp. 165–173.

- Yuyama 1970.

- Stone 2003, p. 471.

- Cole 2005, p. 59.

- Hirakawa 1990, p. 286.

- Silk 2016, p. 216.

- Buswell 2013, pp. 290.

- Burnouf 1852.

- Yuyama 2000, pp. 61-77.

- Lopez (2016b)

- Silk 2012, pp. 125–54.

- Vetter 1999, pp. 129-141.

- Kern 1884.

- Deeg 2012, pp. 133–153.

- Soothill 1930.

- Deeg 2012, p. 146.

- Kato 1975.

- Murano 1974.

- Hurvitz 2009.

- Kuo-lin 1977.

- Kubo 2007.

- Watson 2009.

- Reeves 2008.

- Robert 1997.

- Tola 1999.

- Borsig 2009.

- Deeg 2007.

- Teiser & Stone 2009, p. 237-240.

- Murano 1967, p. 18.

- Sangharakshita 2014, p. chapter 1.

- Obayashi, Kotoku (2002). The Doctrines and Practices of Nichiren Shoshu. Fujinomiya City, Japan: Nichiren Shoshu Overseas Bureau. p. 443.

- Takakusa, Watanabe (1926). Tendai Daishi Zenshu. Tokyo, Japan: Taisho shinshu daizokyo Kanko-Kai.

- Buswell 2013, p. 153.

- Suguro 1998, p. 19.

- Kern 1884, p. 7.

- Apple 2012, p. 162.

- Murano 1967, p. 25.

- Teiser & Stone 2009, p. 8.

- Suguro 1998, p. 31.

- Suguro 1998, pp. 34-35.

- Pye 2003, p. 23.

- Groner 2014, pp. 8-9.

- Williams 1989, p. 155.

- Pye 2003, p. 37-39.

- Suzuki 2015, p. 170.

- Lai 1981, p. 91.

- Pye 2003, p. 40-42.

- Murano 1967, p. 34-35.

- Pye 2003, p. 42-45.

- Pye 2003, p. 48.

- Williams 1989, p. 156.

- Federman 2009, p. 132.

- Lopez 2015, p. 29.

- Murano 1967, pp. 38-39.

- Pye 2003, p. 46.

- Lopez 2015, p. 28.

- Wawrytko 2007, p. 74.

- Zimmermann 1999, p. 162.

- Murano 1967, p. 39.

- Shioiri 1989, pp. 31-33.

- Tamura 1963, p. 812.

- Buswell 2013, p. 654.

- Strong 2007, p. 38.

- Hirakawa 2005, p. 202.

- Lopez & Stone 2019, p. 138-141.

- Lai 1981, p. 459-460.

- Teiser & Stone 2009, p. 12.

- Peach 2002, p. 57-58.

- Silk 2016, p. 150.

- Suguro 1998, pp. 115-118.

- Apple 2012, p. 168.

- Murano 1967, p. 50-52.

- Tamura 2014.

- Pye 2003, p. 51-54.

- Williams 1989, p. 157.

- Lopez & Stone 2019, p. 201.

- Zimmermann 1999, p. 159.

- Suzuki 2016, p. 1162.

- Murano 1967, pp. 65-66.

- Tamura 1989, p. 45.

- Murano 1967, p. 66.

- Tamura 1963, p. 813.

- Shioiri 1989, p. 29.

- Lopez (2016), chapter 1

- Teiser 1963, p. 8.

- Williams 1989, p. 160.

- Benn 2007, p. 59.

- Ohnuma 1998, p. 324.

- Suzuki 2015, p. 1187.

- Murano 1967, pp. 73.

- Chün-fang 1997, p. 414-415.

- Baroni 2002, p. 15.

- Wang 2005, p. 226.

- Murano 1967, pp. 76-78.

- Suguro 1998, p. 170.

- Tay 1980, p. 373.

- Wang 2005, pp. XXI-XXII.

- Shioiri 1989, p. 30.

- Murano 1967, pp. 81-83.

- The Walters Art Museum.

- Williams 1989, p. 151.

- Teiser 2009, p. 21.

- Abe 2015, p. 29, 36, 37.

- Stone 2003, p. 473.

- Kotatsu 1975, p. 88.

- Teiser 2009, pp. 20-21.

- Groner 2014, pp. 3,17.

- Nakamura 1980, p. 190.

- Hirakawa 1990, p. 284.

- Abbot 2013, p. 88.

- Groner 2014, p. 17.

- Stone 1995, p. 19.

- Chen 2011, pp. 71-104.

- Teiser 2009, p. 23.

- Xing 2005, p. 2.

- Hurvitz 1976, p. 239.

- Reeves 2008, p. 14.

- Reeves 2008, p. 1.

- Jessica Ganga (2016), Donald Lopez on the Lotus Sutra, Princeton University Press Blog

- Mochizuki 2011, pp. 1169-1177.

- Groner 2014, p. 5.

- Abbot 2013, p. 87.

- Silk 2001, pp. 87,90,91.

- Kirchner 2009, p. 193.

- "Cooper, Andrew, The Final Word: An Interview with Jacqueline Stone". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Spring 2006. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- Teiser 2009.

- Kim 1985, pp. 3.

- Groner 2014, pp. 1.

- Magnin 1979.

- Williams 1989, p. 162.

- Groner 2000, pp. 199–200.

- Tanahashi 1995, p. 4.

- Stone 2003, p. 277.

- Stone 2009, p. 220.

- Stone 1998, p. 138.

- Tanabe 1989, p. 43.

- Leighton 2005, pp. 85–105.

- Leighton.

- Tanabe 1989, p. 40.

- Leighton 2007, pp. 85–105.

- Yampolsky 1971, pp. 86-123.

- Shields 2013, pp. 512–523.

- Reader, Ian. "JAPANESE NEW RELIGIONS: AN OVERVIEW" (PDF). The World Religions & Spirituality Project (WRSP). Virginia Commonwealth University. p. 16. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- Metraux, Daniel (2010). How Soka Gakkai Became a Global Buddhist Movement: The Internationalization of a Japanese Religion. Virginia Review of Asian Studies. ISBN 0-7734-3758-4.

- Lopez, Donald S, Jr. (2016). The Lotus Sutra: A Biography. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. pp. 232, 109–115, 191–195, 201–215. ISBN 978-0-691-15220-2.

- Stone 2009, p. 227–230.

- Covell, Stephen G. (2014). "Interfaith Dialogue and a Lotus Practitioner: Yamada Etai, the "Lotus Sutra", and the Religious Summit Meeting on Mt. Hiei". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 41 (1): 191–217. doi:10.18874/jjrs.41.1.2014.191-217. JSTOR 23784405.

- Reeves, Gene (Dec 1, 2001). "Introduction: The Lotus Sutra and Process Thought". Journal of Chinese Philosophy. 28 (4): 355. doi:10.1111/0301-8121.00053.

- Groner, Paul; Stone, Jacqueline I (2014). "The Lotus Sutra in Japan". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 41 (1): 2.

- O'Leary, Joseph S. (2003). "Review of Gene Reeves, ed. A Buddhist Kaleidoscope: Essays on the Lotus Sutra". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 30 (-/2): 175–178.

- "A Discussion with Gene Reeves, Consultant, Rissho Kosei-kai and the Niwano Peace Foundation". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace & World Affairs. Georgetown University. November 25, 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- MURUGAPPAN, REVATHI (May 24, 2014). "Lotus Sutra's Dance of Peace". The Star Online. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- Watson 2009, p. xxix.

- Lopez 2016, p. 17, 265.

- Kurata 1987.

- Wang 2005.

- Wang 2005, p. 68.

- Wang 2005, p. 5.

- Paine 1981, p. 41.

- Lim 2014, p. 33.

- Tamura 2009, p. 56.

- Hurvitz 2009, p. 5.

- Yamada 1989.

- Tanabe 1989, p. 105.

- Shioiri 1989, p. 16.

- Rubio 2013.

- Dykstra 1983.

- Mulhern 1989, p. 16.

Sources

- Abe, Ryuchi (2015). "Revisiting the Dragon Princess: Her Role in Medieval Engi Stories and Their Implications in Reading the Lotus Sutra". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 42 (1): 27–70. Archived from the original on 2015-09-07.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Abbot, Terry, trans. (2013), The Commentary on the Lotus Sutra, in: Tsugunari Kubo; Terry Abbott; Masao Ichishima; David Wellington Chappell, Tiantai Lotus Texts (PDF), Berkeley, California: Bukkyō Dendō Kyōkai America, pp. 83–149, ISBN 978-1-886439-45-0

- Apple, James B. (2012), "The Structure and Content of the Avaivartikacakra Sutra and Its Relation to the Lotus Sutra" (PDF), Bulletin of the Institute of Oriental Philosophy, 28: 155–174, archived from the original on 2015-06-01CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Baroni, Helen Josephine (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Zen Buddhism, The Rosen Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-8239-2240-6

- Benn, James A (2007), Burning for the Buddha, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0824823710

- Bielefeldt, Carl (2009), Expedient Devices, the One Vehicle, and the Life Span of the Buddha. In Teiser, Stephen F.; Stone, Jacqueline Ilyse; eds. Readings of the Lotus Sutra, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 9780231142885

- Boucher, Daniel (1998). "G ā ndh ā ri and the Early Chinese Buddhist Translations Reconsidered: The Case of the Saddharmapuṇḍarīka sūtra" (PDF). Journal of the American Oriental Society. 118 (4): 471–506.

- Borsig, Margareta von, trans. (2009), Lotos-Sutra - Das große Erleuchtungsbuch des Buddhismus, Verlag Herder, ISBN 978-3-451-30156-8

- Burnouf, Eugène, trans. (1852), Le Lotus de la Bonne Loi: Traduit du sanskrit, accompagné d'un commentaire et de vingt et un mémoires relatifs au Bouddhisme, Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, ISBN 9780231142885

- Buswell, Robert Jr; Lopez, Donald S. Jr., eds. (2013), Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism., Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691157863CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chen, Shuman (2011). Chinese Tiantai Doctrine on Insentient Things’ Buddha-Nature, Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal 24, 71-104

- Chün-fang, Yü (1997), "Ambiguity of Avalokiteśvara and the Scriptural Sources for the Cult of Kuan-Yin in China" (PDF), Chung Hwa Journal of Buddhism, 10: 409–463

- Cole, Alan (2005), Text as Father: Paternal Seductions in Early Mahayana Buddhist Literature, Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 0520242769

- Deeg, Max (2007), Das Lotos-Sūtra, Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, ISBN 9783534187539

- Deeg, Max (2012), "From scholarly object to religious text - the story of the Lotus-sutra in the West" (PDF), The Journal of Oriental Studies, 22: 133–153

- Dykstra, Yoshiko Kurata (1983), Miraculous tales of the Lotus sutra from ancient Japan : the Dainihonkoku Hokekyōkenki of Priest Chingen, Hirakata City, Osaka-fu, Japan: Intercultural Research Institute, Kansai University of Foreign Studies, ISBN 978-4873350028

- Federman, Asaf (2009), "Literal means and hidden meanings: a new analysis of skillful means" (PDF), Philosophy East and West, 59 (2): 125–141, doi:10.1353/pew.0.0050

- Groner, Paul (2000), Saicho: The Establishment of the Japanese Tendai School, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0824823710

- Groner, Paul; Stone, Jacqueline I. (2014), "Editors' Introduction: The "Lotus Sutra" in Japan", Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 41 (1): 1–23, archived from the original on June 14, 2014

- Hirakawa, Akira; Groner, Paul (trans.; ed.) (1990), A History of Indian Buddhism, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0-8248-1203-4

- Hirakawa, Akira (2005), The rise of Mahayana Buddhism and its relationship to the worship of stupas. In: Paul Williams (Editor), Buddhism: Critical Concepts in Religious Studies Series, Vol. 3, The Origins and Nature of Mahayana Buddhism, London, New York: Routledge, pp. 181–226

- Hurvitz, Leon (2009), Scripture of the Lotus Blossom of the Fine Dharma : The Lotus Sutra) (Rev. ed.), New York: Columbia university press, ISBN 023114895X

- Jamieson, R.C. (2002), "Introduction to the Sanskrit Lotus Sutra Manuscripts" (PDF), Journal of Oriental Studies, 12 (6): 165–173, archived from the original on 2013-04-02CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Kajiyama, Yuichi (2000), "The Saddharmapundarika and Sunyata Thought" (PDF), Journal of Oriental Studies, 10: 72–96

- Karashima, Seishi (2001). A Glossary of Kumarajiva's Translation of the Lotus Sutra, Bibliotheca Philologica et Philosophica Buddhica, The International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology, Vol. IV, Tokyo, p. VII, ISBN 4-9980622-3-9

- Karashima, Seishi (2015), "Vehicle (yāna) and Wisdom (jñāna) in the Lotus Sutra - the Origin of the Notion of yāna in Mahayāna Buddhism" (PDF), Annual Report of The International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University, 18: 163–196, archived from the original on 2017-02-10CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Kato, Bunno; Tamura, Yoshirō; Miyasaka, Kōjirō, trans. (1975), The Threefold Lotus Sutra: The Sutra of Innumerable Meanings; The Sutra of the Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Law; The Sutra of Meditation on the Bodhisattva Universal Virtue (PDF), New York/Tōkyō: Weatherhill & Kōsei Publishing, archived from the original on 2014-04-21CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Kern, Hendrik, trans. (1884), Saddharma Pundarîka or the Lotus of the True Law, Sacred Books of the East, Vol. XXI, Oxford: Clarendon Press, ISBN 9780231142885

- Kern, Hendrik; Nanjio, B.; eds. (1908-1912). Saddharmapuṇḍarīka; St. Pétersbourg: Imprimerie de l'Académie Impériale des Sciences, Bibliotheca Buddhica, 10, Vol.1, Vol. 2, Vol 3, Vol. 4, Vol. 5. (In Nāgarī)

- Kim, Young-Ho (1985), Tao-Sheng's Commentary on the Lotus Sutra: A Study and Translation, dissertation, Albany, NY.: McMaster University, archived from the original on February 3, 2014CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Kirchner, Thomas Yuho; Sasaki, Ruth Fuller (2009), The Record of Linji, University of Hawaii Press, p. 193, ISBN 9780824833190

- Kotatsu, Fujita; Hurvitz, Leon (1975). "One Vehicle or Three". Journal of Indian Philosophy 3 (1/2): 79–166

- Kubo, Tsugunari; Yuyama, Akira, trans. (2007), The Lotus Sutra (PDF), Berkeley, Calif.: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, ISBN 978-1-886439-39-9, archived from the original on 2015-05-21CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Kuo-lin, Lethcoe, ed. (1977), The Wonderful Dharma Lotus Flower Sutra with the Commentary of Tripitaka Master Hsuan Hua, San Francisco: Buddhist Text Translation SocietyCS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Kurata, Tamura; Tamura, Yoshirō; translated by Edna B. (1987), Kurata, Bunsaku; Tamura, Yoshio (eds.), Art of the Lotus Sutra: Japanese masterpieces, Tokyo: Kōsei Pub. Co., ISBN 4333010969

- Lai, Whalen (1981), "The Buddhist "Prodigal Son": A Story of Misconceptions", Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 4 (2): 91–98, archived from the original on August 10, 2014CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Lai, Whalen W. (1981), "The Predocetic "Finite Buddhakāya" in the "Lotus Sūtra": In Search of the Illusive Dharmakāya Therein", Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 49 (3): 447–469

- Leighton, Taigen Dan (2005), "Dogen's Appropriation of Lotus Sutra Ground and Space", Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 32 (1): 85–105, archived from the original on January 9, 2014CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Leighton, Taigen Dan (2007), Visions of Awakening Space and Time, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195320930

- Leighton, Taigen Dan, The Lotus Sutra as a Source for Dogen's Discourse Style, Conference Paper: "Discourse and Rhetoric in the Transformation of Medieval Japanese Buddhism; "thezensite, archived from the original on October 14, 2012, retrieved April 27, 2013CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Lim, Jinyoung; Ryoo, Seong Lyong (2014), K-architecture: tradition meets modernity, Korean Culture and Information Service Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, p. 33, ISBN 9788973755820

- Lopez Jr., Donald S. (2015), Buddhism in Practice (Abridged Edition), Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-1-4008-8007-2

- Lopez, Donald (2016), The Lotus Sutra: A Biography (Kindle ed.), Princeton University Press, ISBN 0691152209

- Lopez Jr., Donald S. (2016b). "The Life of the Lotus Sutra". Tricycle Magazine (Winter).

- Lopez, Donald S.; Stone, Jacqueline I. (2019). Two Buddhas Seated Side by Side: A Guide to the Lotus Sūtra, Princeton University Press

- Mochizuki, Kaie (2011). "How Did the Indian Masters Read the Lotus Sutra? -". Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies. 59 (3): 1169–1177.

- Mulhern, Chieko, "Review: Miraculous Tales of the Lotus Sutra from Ancient Japan. The 'Dainihonkoku hokekyōkenki' of Priest Chingen by Yoshiko Kurata Dykstra", Asian Folklore Studies, 45 (1): 131–133

- Murano, Senchū (trans.) (1974), The Sutra of the Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Law, Tokyo: Nichiren Shu Headquarters, ISBN 2213598576

- Murano, Senchu (1967), "An Outline of the Lotus Sūtra", Contemporary Religions in Japan, 8 (1): 16–84, archived from the original on 2014-08-26CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Nakamura, Hajime (1980), Indian Buddhism: A Survey With Bibliographical Notes, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited

- Nattier, Jan (2008), A guide to the Earliest Chinese Buddhist Translations (PDF), International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology, Soka University, ISBN 9784904234006, archived from the original on July 12, 2012CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Ohnuma, Reiko (1998), "The Gift of the Body and the Gift of Dharma", History of Religions, 37 (4): 323–359, JSTOR 3176401

- Paine, Robert Treat; Soper, Alexander (1981), The art and architecture of Japan (3. ed. / with rev. and updated notes and bibliography to part one by D.B. Waterhouse. ed.), New Haven [u.a.]: Yale Univ. Press, p. 41, ISBN 9780300053333

- Peach, Lucinda Joy (2002), "Social responsibility, sex change, and salvation: Gender justice in the Lotus Sūtra", Philosophy East and West, 52: 50–74, doi:10.1353/pew.2002.0003, archived from the original on 2014-08-29CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Pye, Michael (2003), Skilful Means - A concept in Mahayana Buddhism, Routledge, ISBN 0203503791

- Reeves, Gene, trans. (2008), The Lotus Sutra: A Contemporary Translation of a Buddhist Classic, Boston: Wisdom Publications, ISBN 0-86171-571-3

- Robert, Jean-Noël (1997), Le Sûtra du Lotus: suivi du Livre des sens innombrables, Paris: Fayard, ISBN 2213598576

- Robert, Jean Noël (2011), "On a Possible Origin of the "Ten Suchnesses" List in Kumārajīva's Translation of the Lotus Sutra", Journal of the International College for Postgraduate Buddhist Studies, 15: 63

- Rubio, Carlos (2013), "The Lotus Sutra in Japanese literature: A spring rain" (PDF), Journal of Oriental Philosophy, 23: 120–140

- Shields, James Mark (2013), Political Interpretations of the Lotus Sutra. In: Steven M. Emmanuel, ed. A Companion to Buddhist Philosophy, London: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 9781118324004

- 子規·正岡 (Shiki Masaoka) (1983), 歌よみに与ふる書 (Utayomi ni atauru sho), Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, p. 17

- Shioiri, Ryodo (1989), The Meaning of the Formation and Structure of the Lotus Sutra. In: George Joji Tanabe; Willa Jane Tanabe, eds. The Lotus Sutra in Japanese Culture, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 15–36, ISBN 978-0-8248-1198-3

- Silk, Jonathan (2001), "The place of the Lotus Sutra in Indian Buddhism" (PDF), The Journal of Oriental Studies, 11: 87–105, archived from the original on August 26, 2014CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Silk, Jonathan A. (2012), "Kern and the Study of Indian Buddhism With a Speculative Note on the Ceylonese Dhammarucikas" (PDF), The Journal of the Pali Text Society, XXXI: 125–54

- Silk, Jonathan; Hinüber, Oskar von; Eltschinger, Vincent; eds. (2016). "Lotus Sutra", in Brill's Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Volume 1: Literature and Languages. Leiden: Brill. pp. 144–157

- Soothill, William Edward, trans. (1930), The Lotus of the Wonderful Law or The Lotus Gospel, Clarendon Press, pp. 15–36 (Abridged)

- Stone, Jacqueline (1995), "Medieval Tendai Hongaku Thought and the New Kamakura Buddhism" (PDF), Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 22 (1–2)

- Stone, Jacqueline, I. (1998), Chanting the August Title of the Lotus Sutra: Daimoku Practices in Classical and Medieval Japan. In: Payne, Richard, K. (ed.); Re-Visioning Kamakura Buddhism, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 116–166, ISBN 0-8248-2078-9, archived from the original on 2015-01-04CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Stone, Jacqueline, I. (2003), "Lotus Sutra". In: Buswell, Robert E. ed.; Encyclopedia of Buddhism vol. 1, Macmillan Reference Lib., ISBN 0028657187

- Stone, Jacqueline Ilyse (2003), Original Enlightenment and the Transformation of Medieval Japanese Buddhism, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-2771-7

- Stone, Jacqueline, I. (2009), Realizing This World as the Buddha Land, in Teiser, Stephen F.; Stone, Jacqueline Ilyse; eds.; Readings of the Lotus Sutra, Columbia University Press, pp. 209–236, ISBN 0028657187

- Strong, John (2007), Relics of the Buddha, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-3139-1

- Suguro, Shinjo; Nichiren Buddhist International Center, trans. (1998), Introduction to the Lotus Sutra, Jain Publishing Company, ISBN 0875730787

- Suzuki, Takayasu (2016), "The Saddharmapundarika as the Prediction of All the Sentient Beings' Attaining Buddhahood: With Special Focus on the Sadaparibhuta-parivarta", Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies (印度學佛教學研究.), 64 (3): 1155–1163

- Suzuki, Takayasu (2015), "Two parables on "The wealthy father and the poor son" in the Saddharmapundarika and the Mahaberisutra", Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies (印度學佛教學研究.), 63 (3): 169–176

- Suzuki, Takayasu (2015), "The Compilers of the Bhaisajyarajapurvayoga-parivarta Who Did Not Know the Rigid Distinction between Stupa and Caitya in the Saddharmapundarika", Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies (印度學佛教學研究.), 62 (3): 1185–1193

- Tamura, Yoshiro (1963), "The Characteristic of the Bodhisattva Concept in the Lotus Sutra - The Apostle-idea", Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies (印度學佛教學研究.), 11 (2): 816–810

- Tamura, Yoshio (1989), The Ideas of the Lotus Sutra, In: George Joji Tanabe; Willa Jane Tanabe, eds. The Lotus Sutra in Japanese Culture, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 37-, ISBN 978-0-8248-1198-3

- Tamura, Yoshio; Reeves, Gene (ed) (2014), Introduction to the Lotus Sutra, Boston: Wisdom Publications, ISBN 9781614290803CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Tanabe, George Joji; Tanabe, eds. (1989). The Lotus Sutra in Japanese Culture. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824811983.

- Tanahashi, Kazuaki (1995), Moon in a Dewdrop, p. 4, ISBN 9780865471863

- Tay, C. N. (1980), "Review: The Lotus Sutra in Its Latest Translation Scripture of the Lotus Blossom of the Fine Dharma by Leon Hurvitz", History of Religions, 19 (4): 372–377, doi:10.1086/462858

- Teiser, Stephen F.; Stone, Jacqueline Ilyse (2009), Interpreting the Lotus Sutra; in: Teiser, Stephen F.; Stone, Jacqueline Ilyse; eds. Readings of the Lotus Sutra, New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 1–61, ISBN 9780231142885CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The English Buddhist Dictionary Committee (2002), The Soka Gakkai Dictionary of Buddhism, Tōkyō: Soka Gakkai, ISBN 978-4-412-01205-9

- Portable Buddhist Shrine, The Walters Art Museum, archived from the original on 2017-09-01, retrieved 2012-11-27

- Tola, Fernando; Dragonetti, Carmen (1999), El Sūtra del Loto de la verdadera doctrina: Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra, México, D.F.: El Colegio de México: Asociación Latinoamericana de Estudios Budistas, ISBN 968120915X

- Vaidya, P. L. (1960), Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtram, Darbhanga: The Mithila Institute of Post-Graduate Studies and Research in Sanskrit Learning, ISBN 968120915X (Romanized Sanskrit)

- Vetter, Tilmann (1999), "Hendrik Kern and the Lotus Sutra" (PDF), Annual Report of The International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University, 2: 129–142, archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-01-05

- Wang, Eugene Yuejin (2005), Shaping the Lotus Sutra: Buddhist Visual Culture in Medieval China, University of Washington Press, ISBN 978-0-295-98462-9

- Watson, Burton, tr. (1993), The Lotus Sutra, Columbia University Press, ISBN 023108160X

- Watson, Burton, tr. (2009), The Lotus Sutra and Its Opening and Closing Sutras, Tokyo: Soka Gakkai, ISBN 023108160X

- Wawrytko, Sandra (2007), "Holding Up the Mirror to Buddha-Nature: Discerning the Ghee in the Lotus Sutra", Dao: A Journal of Comparative Philosophy, 6: 63–81, doi:10.1007/s11712-007-9004-2

- Weinstein, Stanley (1977), "Review: Scripture of the Lotus Blossom of the Fine Dharma, by Leon Hurvitz", The Journal of Asian Studies, 37 (1): 89–90, doi:10.2307/2053331

- Williams, Paul (1989), Mahāyāna Buddhism: the doctrinal foundations, 2nd Edition, Routledge, ISBN 9780415356534

- Xing, Guang (2005). Problem of the Buddha´s Short Lifespan, World Hongming Philosophical Quarterly 12, 1-12

- Yamada, Shozen (1989), Tanabe, George J; Tanabe, Willa Jane (eds.), Poetry and Meaning: Medieval Poets and the Lotus Sutra (Repr. ed.), Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0824811984

- Yampolsky, Philip B. [translator] (1971 ), Zen Master Hakuin's Letter in Answer to an Old Nun of the Hokke [Nichiren] Sect. In The Zen Master Hakuin: Selected Writings, New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 86–123

- Yuyama, Akira (1970). A Bibliography of the Sanskrit-Texts of the Sadharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra. Faculty of Asian Studies in Association With Australian National University, Canberra, Australia

- Yuyama, Akira (1998), Eugene Burnouf: The Background to his Research into the Lotus Sutra, Bibliotheca Philologica et Philosophica Buddhica, Vol. III (PDF), Tokyo: The International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology, ISBN 4-9980622-2-0, archived from the original on 2007-07-05CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Zimmermann, Michael (1999), The Tathagatagarbhasutra: Its Basic Structure and Relation to the Lotus Sutra (PDF), Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University for the Academic Year 1998, pp. 143–168, archived from the original on October 8, 2011CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Zürcher, Erik (2006). The Buddhist Conquest of China, Sinica Leidensia (Book 11), Brill; 3rd edition. ISBN 9004156046

Further reading

- Hanh, Thich Nhat (2003). Opening the heart of the cosmos: insights from the Lotus Sutra. Berkeley, Calif.: Parallax. ISBN 1888375337.

- Hanh, Thich Nhat (2009). Peaceful action, open heart: lessons from the Lotus Sutra. Berkeley, Calif.: Parallax Press. ISBN 1888375930.

- Ikeda, Daisaku; Endo, Takanori; Saito, Katsuji; Sudo, Haruo (2000). Wisdom of the Lotus Sutra: A Discussion, Volume 1. Santa Monica, CA: World Tribune Press. ISBN 978-0915678693.

- Lopez, Donald S.; Stone, Jacqueline I. (2019). Two Buddhas Seated Side by Side: A Guide to the Lotus Sūtra, Princeton University Press

- Niwano, Nikkyō (1976). Buddhism for today : a modern interpretation of the Threefold Lotus sutra (PDF) (1st ed.). Tokyo: Kosei Publishing Co. ISBN 4333002702. Archived from the original on 2013-11-26.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Sangharakshita (2014). The Drama of Cosmic Enlightenment: Parables, Myths, and Symbols of the White Lotus. Cambridge: WIndhorse Publications. ISBN 9781909314344.

- Tamura, Yoshiro (2014). Introduction to the lotus sutra. [S.l.]: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 1614290806.

- Tanabe, George J.; Tanabe, Willa Jane (ed.) (1989). The Lotus Sutra in Japanese Culture. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1198-4.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Tola, Fernando, Dragonetti, Carmen (2009). Buddhist positiveness: studies on the Lotus Sūtra, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-3406-4.

External links

| Chinese Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- An 1884 English translation from Sanskrit by H.Kern from the Sacred Texts Web site

- An English translation by the Buddhist Text Translation Society