List of works by Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) was one of the leading artists of the High Renaissance. Fifteen artworks are generally attributed either in whole or in large part to him. However, it is believed that he made many more, only for them to be lost over the years or remain unidentified. The authorship of several paintings traditionally attributed to Leonardo is disputed. Two major works are known only as copies. Works are regularly attributed to Leonardo with varying degrees of credibility. None of Leonardo's paintings are signed. The attributions here draw on the opinions of various scholars.[1]

The small number of surviving paintings is due in part to Leonardo's frequently disastrous experimentation with new techniques and his chronic procrastination. Nevertheless, these few works together with his notebooks, which contain drawings, scientific diagrams, and his thoughts on the nature of painting, comprise a contribution to later generations of artists rivalled only by that of his contemporary, Michelangelo.

Major extant works

| * | Collaborative work |

|---|---|

| º | Potentially collaborative work |

| Image[lower-alpha 1] | Title | Dating | Medium, Dimensions[2] |

Location[2] | Attribution status[2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The Annunciation | c. 1472–1476[d 1] | Painting Oil and tempera on poplar panel 98 × 217 cm (38.25 × 84.62 in) |

Uffizi, Florence |

|

|

Madonna of the Carnation | c. 1472–1478[d 2] | Painting Oil on poplar panel 62 × 47.5 cm (24.13 x 18.5 in) |

Alte Pinakothek, Munich |

|

|

The Baptism of Christ* | c. 1474–1478[d 3] | Painting Oil and tempera on poplar panel 177 × 151 cm |

Uffizi, Florence |

|

|

Ginevra de' Benci | c. 1474–1480[d 4] | Painting Oil and tempera on poplar panel 38.8 × 36.7 cm (15.3 × 14.4 in) |

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. |

|

|

Benois Madonna | c. 1478–1481[d 5] | Painting Oil on wood panel, transferred to canvas 49.5 × 33 cm |

Hermitage, Saint Petersburg |

|

|

The Adoration of the Magi (unfinished) |

c. 1478–1482[d 6] | Painting Oil (underpainting) on wood panel 240 × 250 cm (96 × 97 in) |

Uffizi, Florence |

|

|

Saint Jerome in the Wilderness (unfinished) |

c. 1480–1490[d 7] | Painting Tempera and oil on walnut panel 103 × 75 cm (41 × 30 in) |

Vatican Museums |

|

|

Madonna Litta | c. 1481–1495[d 8] | Painting Tempera (and oil) on poplar panel 42 × 33 cm |

Hermitage, Saint Petersburg |

|

.jpg) |

Virgin of the Rocks (Louvre version) |

c. 1483–1493[d 9] | Painting Oil on wood panel, transferred to canvas 199 × 122 cm (78.3 × 48.0 in) |

Louvre, Paris |

|

|

Portrait of a Musicianº (unfinished) |

c. 1483–1487[d 10] | Painting Tempera and oil on walnut panel 45 × 32 cm |

Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan |

|

|

Lady with an Ermine | c. 1489–1491[d 11] | Painting Oil on walnut panel 54 × 39 cm |

Czartoryski Museum, Kraków |

|

-_la_Belle_Ferroniere.jpg) |

La Belle Ferronnière | c. 1490–1498[d 12] | Painting Oil on walnut panel 62 × 44 cm |

Louvre, Paris |

|

.png) |

Virgin of the Rocks* (London version) |

c. 1491–1508[d 13] | Painting Oil on parqueted poplar panel 189.5 × 120 cm (74.6 × 47.25 in) |

National Gallery, London |

|

|

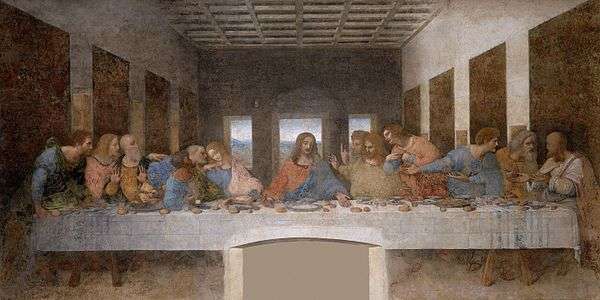

The Last Supper | c. 1492–1498[d 14] | Fresco Tempera on gesso, pitch and mastic 460 × 880 cm (181 × 346 in) |

Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan |

|

|

Sala delle Asse | c. 1497–1499[d 15] | Fresco Tempera on plaster |

Castello Sforzesco, Milan |

|

|

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Saint John the Baptist | c. 1499–1508[d 16] | Chalk drawing Charcoal, black and white chalk on tinted paper, mounted on canvas 142 × 105 cm (55.7 × 41.2 in) |

National Gallery, London |

|

|

Portrait of Isabella d'Este | c. 1499–1500[d 17] | Chalk drawing Black and red chalk, yellow pastel chalk on paper 61 × 46.5 cm |

Louvre, Paris |

|

|

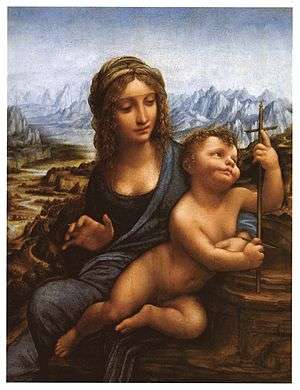

The Madonna of the Yarnwinder*

|

c. 1499–1508[d 18] | Painting Oil on walnut panel 48.9 × 36.8 cm |

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh[lower-alpha 6] |

|

|

The Madonna of the Yarnwinder*

|

c. 1501–1508[d 19] | Painting Oil on wood panel (transferred to canvas and later re-laid on panel) 50.2 × 36.4 cm |

Private collection, New York City |

|

|

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne | c. 1501–1519[d 20] | Painting Oil on wood panel 168 × 112 cm (66.1 × 44.1 in) |

Louvre, Paris |

|

|

Mona Lisa | c. 1502–1516[d 21] | Painting Oil on cottonwood (poplar) panel 76.8 × 53.0 cm (30.2 × 20.9 in) |

Louvre, Paris |

|

|

Salvator Mundiº | c. 1504–1510[d 22] | Painting Oil on wood panel 65.6 x 45.4 cm (25.8 × 17.9 in) |

Unknown |

|

|

La Scapigliata (unfinished) |

c. 1506–1508[d 23] | Painting Earth, amber and white lead on wood panel 24.7 × 21 cm (9.7 × 8.3 in) |

Galleria Nazionale, Parma | |

|

Saint John the Baptist | c. 1507–1516[d 24] | Painting Oil on walnut panel 69 × 57 cm (27.2 × 22.4 in) |

Louvre, Paris |

|

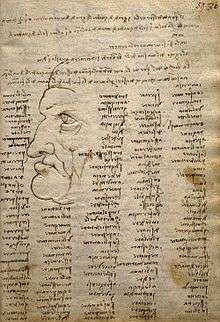

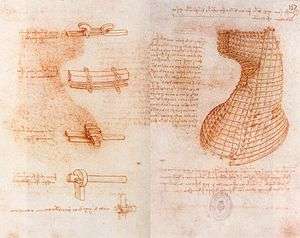

Manuscripts

| Sample image | Details | Pages | Notes | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

1,119 |

12 volumes, collated by the sculptor Pompeo Leoni. |

1478–1519 |

|

|

153 | 1478–1518 | |

|

283 | 1480–1518 | ||

|

55 (originally 62) | c. 1487–1490 | ||

|

354 |

Five pocket notebooks bound into three volumes, here listed in chronological order.

|

1487–1505 | |

|

|

more than 2500 |

12 volumes, here listed in chronological order.

|

1488–1505 |

|

Two volumes, rediscovered in 1966. |

1490s–1504 | ||

|

|

Two volumes, taken out of Paris Manuscripts A and B and sold to the Earl of Ashburnham, who returned them to Paris in 1890. |

c. 1492 | |

|

18 |

Originally part of Paris Manuscript B; probably stolen by Count Guglielmo Libri in around 1840–1847.[43] |

dated 1505 | |

|

72 | 1506–1510 | ||

|

An anthology of writings by Leonardo compiled after his death by his pupil Francesco Melzi. An abridged version was published in 1651 as a treatise on painting (Trattato della Pittura).[44] |

c. 1530 |

Lost works

| Image | Details | Notes | Dating |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Works without consensus on attribution

| Image | Details | Attribution Status and Notes | Dating |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

|

||

|

|

| |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

|

|

See also

- Portraits of Leonardo da Vinci

Notes

Sources for dating

- The Annunciation

- Kemp 2019, p. 6: c. 1473–1474

- Marani 2003, p. 338: c. 1472–1475

- Syson 2011, p. 15: c. 1472–1476

- Zöllner 2019, p. 216: c. 1473–1475

- Madonna of the Carnation

- Kemp 2019, p. 15: c. 1475

- Marani 2003, p. 338: between 1473 and 1478

- Syson 2011, p. 16: c. 1477–1478

- Zöllner 2019, p. 214: c. 1472–1478

- The Baptism of Christ

- Kemp 2019, p. 3: Leonardo c. 1474–1476

- Marani 2003, p. 338: Leonardo c. 1475–1478

- Syson 2011, p. 184: Verrocchio and Leonardo c. 1468–1477

- Zöllner 2019, p. 215: Verrocchio c. 1470–1472, Leonardo c. 1475

- Covi 2005, p. 186: c. 1469–1472 by Verrocchio, then resumed by Leonardo perhaps mid-1470s

- Ginevra de' Benci

- Kemp 2019: c. 1478

- Marani 2003, p. 338: c. 1474/1475–1476

- Syson 2011, p. 48: c. 1474/1478

- Zöllner 2019, p. 218: c. 1478–1480

- Benois Madonna

- Kemp 2019, p. 21: c. 1478–1480

- Marani 2003, p. 338: probably after March 1481

- Syson 2011, p. 18: c. 1481 onwards

- Zöllner 2019, p. 217: c. 1478–1480

- The Adoration of the Magi

- Kemp 2019, p. 27: c. 1481–1482

- Marani 2003, p. 338: 1481

- Syson 2011, p. 56: c. 1480–1482

- Zöllner 2019, p. 222: 1481/1482

- Saint Jerome in the Wilderness

- Kemp 2019, p. 31: c. 1481–1482

- Marani 2003, p. 338: probably c. 1480

- Syson 2011, p. 139: c. 1488–1490

- Zöllner 2019, p. 221: c. 1480–1482

- Madonna Litta

- Kemp 2019, p. 39: c. 1495

- Marani 2003: Not in checklist

- Syson 2011, p. 222: c. 1491–1495

- Zöllner 2019, p. 227: c. 1490

- Virgin of the Rocks (Louvre version)

- Kemp 2019, p. 41: c. 1483–1493

- Marani 2003, p. 339: between 1483 and 1486

- Syson 2011, p. 164: 1483–c. 1485

- Zöllner 2019, p. 223: 1483–1484/1485

- Portrait of a Musician

- Kemp 2019, p. 47: c. 1483–1486

- Marani 2003, p. 339: c. 1485

- Syson 2011, p. 95: c. 1486–1487

- Zöllner 2019, p. 225: c. 1485

- Lady with an Ermine

- Kemp 2019, p. 49: c. 1491

- Marani 2003, p. 339: 1489–1490

- Syson 2011, p. 111: c. 1489–1490

- Zöllner 2019, p. 226: 1489/1490

- La Belle Ferronnière

- Kemp 2019, p. 57: c. 1498

- Marani 2003, p. 339: c. 1490–1495 or 1495–1496

- Syson 2011, p. 123: c. 1493–1494

- Zöllner 2019, p. 228: c. 1496–1497

- Virgin of the Rocks (London version)

- Kemp 2019, p. 153: c. 1495–1508

- Marani 2003, p. 340: 1491/1494, finished by 1508

- Syson 2011, p. 164: c. 1491/1492–1499 and 1506–1508

- Zöllner 2019, p. 229: c. 1495–1499 and 1506–1508

- The Last Supper

- Kemp 2019, p. 67: c. 1495–1497

- Marani 2003, p. 339: between 1494 and 1498

- Syson 2011, p. 252: 1492–1497/1498

- Zöllner 2019, p. 230: c. 1495–1498

- Sala delle Asse

- Kemp 2019, p. 63: c. 1498

- Marani 2003, p. 339: c. 1497–1498

- Syson 2011, p. 43: c. 1498

- Zöllner 2019, p. 233: c. 1498–1499

- Virgin and Child with SS. Anne and John the Baptist

- Kemp 2019, p. 157: c. 1507–1508

- Syson 2011, p. 89: c. 1499–1500

- Zöllner 2019, p. 234: 1499–1500 or c. 1508

- Chapman & Faietti 2010: c. 1506–1508

- Marani 2003, p. 339: c. 1499–1506

- Portrait of Isabella d'Este

- Kemp 2019, p. 101: 1500

- Marani 2003, p. 339: End of 1499 / early 1500

- Syson 2011, p. 44: c. 1499–1500

- Zöllner 2019, p. 236: December 1499 – March 1500

- Madonna of the Yarnwinder (Buccleuch version)

- Kemp 2019, p. 103: c. 1501–1508

- Marani 2003, p. 339: No date given

- Syson 2011, p. 294: 1499 onwards

- Zöllner 2019, p. 239: c. 1501–1507

- Madonna of the Yarnwinder (Lansdowne version)

- Kemp 2019, p. 103: c. 1501–1508

- Marani 2003, p. 339: No date given

- Syson 2011: No date given

- Zöllner 2019, p. 238: c. 1501–1507

- Virgin and Child with Saint Anne

- Kemp 2019, p. 161: c. 1508–1516

- Marani 2003, p. 340: c. 1510–1513

- Syson 2011, p. 70: c. 1501 onwards

- Zöllner 2019, p. 244: c. 1503–1519

- Mona Lisa

- Kemp 2019, p. 127: c. 1503–1515

- Marani 2003, p. 340: c. 1503–1504;1513–1514

- Syson 2011, p. 48: c. 1502 onwards

- Zöllner 2019, p. 240: c. 1503–1506;1510

- Salvator Mundi

- Kemp 2019, p. 149: c. 1504–1510

- Marani 2003: Not in checklist; Lost at the time of publication.

- Syson 2011, p. 300: c. 1499 onwards

- Zöllner 2019, p. 250: c. 1507 onwards

- La Scapigliata

- Kemp 2019: Not listed

- Marani 2003, p. 340: c. 1508

- Syson 2011, p. 198: No date given

- Zöllner 2019: Not in checklist

- Saint John the Baptist

- Kemp 2019, p. 189: c. 1507–1514

- Marani 2003, p. 340: c. 1508

- Syson 2011, p. 63: c. 1500 onwards

- Zöllner 2019, p. 248: c. 1508–1516

Sources for attribution status

- Sort by size of the original

- Generally thought to be the earliest extant work by Leonardo. The work was traditionally attributed to Verrocchio until 1869. It is now almost universally attributed to Leonardo. Attribution proposed by Liphart, accepted by Bode, Lubke, Muller-Walde, Berenson, Clark, Goldscheider and others.[1]

- It is generally accepted as a Leonardo, but has some overpainting possibly by a Flemish artist.[1]

- Martin Kemp claims that the Gallery exhibited the Madonna Litta, on loan from the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, as an autograph work, even though the National Gallery's own curators believed it to be by a pupil, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio.[8]

- Generally accepted as postdating the version in the Louvre, and produced in collaboration with Ambrogio de Predis and perhaps others.[1] Some consider it the work of Leonardo's workshop under his direction. The date is not universally agreed.

- On long-term loan from the Duke of Buccleuch collection[17]

- Leonardo da Vinci and an anonymous 16th-century painter (Syson 2011, p. 294); Workshop of Leonardo after a design by Leonardo (Zöllner 2019, p. 239)

- Leonardo was documented as working on a painting of this subject in Florence in 1501; it appears to have been delivered to its patron in 1507. This and the Lansdowne Madonna are the most likely candidates for being that work, but neither is considered to be wholly autograph. Scientific examination has revealed "strikingly complex and similar" underdrawings in both versions, suggesting that Leonardo was involved in the making of both.[18] The use of walnut wood suggests the earlier terminus post quem of 1499, as Leonardo's. Milanese paintings are on this support.[19]

- Salaì after a design by Leonardo (Zöllner 2019, p. 238)

- Previously presumed to be a later copy of the lost original painting. Purchased in 2005 and restored, it has gained acceptance as Leonardo's original. Pentimenti (changes to the composition) were found in the thumb of Christ's right hand and elsewhere which are indicators of the painting's status as an "original".[23] The painting set a new record for sale price (US$450 million) when auctioned by Christie's in 2017.[24][25] Matthew Landrus considers it to be primarily the work of Bernardino Luini.[26]

- Follower of Leonardo (Syson 2011, p. 198, n. 9); "ascribed today to Leonardo" (Marani 2003, p. 140)

References

- della Chiesa, Angela Ottino (1967). The Complete Paintings of Leonardo da Vinci. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-008649-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marani 2003, pp. 338–340; Zöllner 2019, pp. 214–251.

- Zöllner 2019, p. 215.

- Zöllner 2019, p. 218–219.

- Marani 2003, p. 338: "Attribution to Leonardo is unchallenged."

- Zöllner 2019, p. 222.

- Marani 2003, p. 338: "Attribution to Leonardo has never been seriously questioned."

- "National Gallery in London accused of altering attribution of Hermitage's 'Leonardo' for 2011 blockbuster show". www.theartnewspaper.com. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- Marani 2003, p. 339: "Attribution to Leonardo is unchallenged."

- Zöllner 2019, p. 225.

- Zöllner 2019, p. 226.

- Zöllner 2019, p. 228.

- Marani 2003, pp. 175–178.

- Marani 2003, p. 339: "Attribution to Leonardo has never been contested."

- Marani 2003, p. 339: "Unanimously recognized as the only surviving fragments by Leonardo for this room."

- Marani 2003, p. 339: "Attribution to Leonardo is unanimous."

- Zöllner 2019, p. 239.

- Kemp 2011, 253

- Syson 2011, 294

- Marani 2003, p. 340: "Although the painting's condition is poor, it should be considered a very damaged original by Leonardo."

- Marani 2003, p. 340: "Unanimously attributed to Leonardo, although there is little agreement on its date."

- For a partial list of scholars who accept the attribution, see Bailey, Martin (31 October 2011). "Leonardo's Saviour of the World rediscovered in New York". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

- Syson 2011, 302

- Andrews, Travis M. (15 November 2017). "Long-lost da Vinci painting fetches $450 million, a world record". Washington Post. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Holland, Oscar (2017-11-16). "Rare Da Vinci painting smashes world records with $450 million sale". CNN. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Who Really Painted 'Salvator Mundi'? An Oxford Art Historian Says It Was Leonardo's Assistant | artnet News". artnet News. 2018-08-07. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- Zöllner 2019, p. 248.

- "The Forster Codices: Leonardo da Vinci's Notebooks at the V&A". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- "Paris Manuscript B". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "Paris Manuscript C". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "Paris Manuscript A". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "Paris Manuscript H". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "Paris Manuscript M". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "Paris Manuscript L". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "Paris Manuscript K". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "Paris Manuscript I". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "Paris Manuscript D". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "Paris Manuscript F". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "Paris Manuscript E". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "Paris Manuscript G". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "Codex Madrid I". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "Codex Madrid II". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- Bambach 2003, p. 723.

- "Codex Urbinas and lost Libro A". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- Marani 2000, p. 431

- Rubin & Wright 1999, pp. 84 and 118, n. 25

- Farmer, Brit Mccandless (26 May 2019). "From the archives: Looking for the lost Leonardo". CBS News. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- Shearman 1992, p. 33.

- Delieuvin 2012, cat. 80

- Delieuvin 2012, cat. 81

- "St John the Baptist". Art UK. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- Arasse, Daniel (1997). Leonardo da Vinci. Konecky & Konecky. ISBN 978-1-56852-198-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Adams, James (October 13, 2005). "Montreal art expert identifies da Vinci drawing". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2009-10-14.

- "The Mark of a Masterpiece" by David Grann, The New Yorker, vol. LXXXVI, no. 20, July 12 & 19, 2010, ISSN 0028-792X

- Byrne, Paul (2015-11-30). "Portrait hailed as Da Vinci masterpiece is actually grumpy Bolton checkout girl". mirror. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- Pedretti, Carlo; Taglialagamba, Sara (2017). Leonardo da Vinci: the "Virgin of the rocks" in the Cheramy version: its history & critical fortune. Poggio a Caiano: CB edizioni. ISBN 9788897644538.

- Arie, Sophie (16 February 2005). "Fingerprint puts Leonardo in the frame". The Guardian. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- "A lost Leonardo? Top art historian says maybe". Universal Leonardo. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- Bertelli, Carlo (November 19, 2005). "Due allievi non fanno un Leonardo" (in Italian). Il Corriere della Sera. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- MacKinnon, Nick (1993). "The Portrait of Fra Luca Pacioli". The Mathematical Gazette. 77 (479): 140–43, 146–49, 154, 165, 183, 184, 186–87, 197–205, 214. doi:10.2307/3619717. JSTOR 3619717.

- "ritratto Pacioli". www.ritrattopacioli.it (in Italian).

- Livio, Mario (2003) [2002]. The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, the World's Most Astonishing Number (First trade paperback ed.). New York City: Broadway Books. pp. 130–131, 138. ISBN 0-7679-0816-3.

- Bo, Gianfranco. "Il sorriso di Pacioli". utenti.quipo.it (in Italian).

- Stephane Fitch DaVinci's Fingerprints, 12.22.03 accessed 7 July 2009. Martin Kemp, the expert on Leonardo's fingerprints, had not examined the painting when the article was written.

- A similar image, without the tormentors, is in the Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.

- "'Early Mona Lisa' painting claim disputed". BBC News. 27 September 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- Pedretti, Carlo, ed. (1987). Leonardo Da Vinci: Drawings of Horses and Other Animals from the Royal Library at Windsor Castle. London: Harcourt Brace. p. 185. ISBN 0384-45284-1.

Fig 111 and 112 Unpublished fragmentary wax model of an equestrian portrait of Charles d'Amboise attributed to Leonardo, said to have come from the Melzi estate at Vaprio d'Adda. London, Private collection (formally Sangiorgi collection in Rome).

- "'Horse and Rider' Discovered Leonardo Da Vinci Sculpture". Huffington Post. 14 August 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- Solari, Ernesto (2016). Leonardo da Vinci Horse and Rider Il "Monumento" a Charles d'Amboise. Milan: Colibri Edizioni. p. 28. ISBN 978-88-97206-33-0.

Carlo Pedretti: In my opinion, this wax model is by Leonardo himself, and to my knowledge it has not been seen by other scholars.

- "Leonardo da Vinci's 'Horse and Rider'". BBC News. 28 August 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- Kazakina, Katya (2 October 2019). "This DaVinci Statue Could Go for $50 Million. But Is It Real?". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2 October 2019 – via Fortune.

- Zerner, Henri (25 September 1997). "The Vision of Leonardo". The New York Review of Books. 44 (14): 67.

no existing sculpture can be attributed to him with any certainty. [... the Bust of Christ as a Youth] was unfortunately placed in the exhibition next to a bizarre object, a wax statuette of a rider on a bucking horse never before seen in public. In the explanatory label, the statuette was said to have belonged to Francesco Melzi, a student and companion of Leonardo, a provenance unfortunately based on hearsay. [...] I fail to see the point of presenting to the uninformed visitor highly debatable hypotheses as if they were confirmed.

- Holmstrom, David (24 March 1997). "Putting Leonardo's Inventions to the test: Boston's Museum of Science looks at the breathtaking scope of Leonardo da Vinci's work, though the authenticity of some objects is in question". The Christian Science Monitor. ProQuest 405615445.

CONTROVERSIAL WORK: Whether Leonardo made this small wax figure is a source of contention among experts. Although the piece is unsigned, it is attributed to him in the exhibit.

(subscription required) - Yemma, John (23 February 1997). "Leonardo on tour: the good, the bad ... and the phony? Art historians question attribution of some works headed for Boston show". The Boston Globe. p. A.1.

at least one of the two sculptures on display in the art gallery at Science Park beginning March 3 have caused grave doubts among some art historians. [...] The labels on the paintings, Ackerman warned museum officials, were simply too generous, linking dubious and contested works from private collections too closely with Leonardo and other Italian masters. [...] after weeks of struggling over wording, museum officials altered some of the labels to introduce more skepticism [... The Wax Horse] is "attributed to Leonardo." Not so fast, said Jack Wasserman, an art historian at Temple University in Philadelphia. "There is no single work of sculpture which Leonardo worked on that survived to today," Wasserman said. "Yes, it could be 'attributed to' Leonardo, but you need to have a compelling reason for doing so. Since nothing survived, there is no way to judge a piece of sculpture like this."

(subscription required) - Panza, Pierluigi (19 October 2016). "La scultura equestre di Leonardo Esposizione tra genio e mistero". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Gatti, Chiara (19 October 2016). "Arriva l'uomo a cavallo di Leonardo Da Vinci che divide i critici". la Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 22 February 2017.

Presentata come una rivelazione esclusiva, è contestata da molti esperti. [...] Vittorio Sgarbi non nasconde i suoi dubbi sull'attribuzione al maestro toscano [...] Pietro Marani: Non ci sono evidenze, né si possono fare confronti poiché non esistono dati d'appoggio, esemplari sicuri.

- Sturman, Shelley; May, Katherine; Luchs, Alison (2017). "The Budapest Horse: Beyond the Leonardo da Vinci Question". In Helmstutler Di Dio, Kelley (ed.). Making and Moving Sculpture in Early Modern Italy. Routledge. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-351-55951-5.

- Pedretti, Carlo (10 July 1985). "Wax model of Horse and Rider". Letter to Mr. Paul J. Wagner. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014.

- Solari, Ernesto (2016). Leonardo da Vinci : Horse and rider : il "monumento" a Charles d'Amboise. Leonardo, da Vinci, 1452-1519,, Palazzo delle Stelline (Prima edizione ed.). Paderno Dugnano (Mi). ISBN 9788897206330. OCLC 962823523.

- Self-portrait of Leonardo, Surrentum Online, accessed 2010-11-06

- Scaramella, A. D. "Artwork Analysis self Portrait in Red Chalk by Leonardo Da Vinci". Finearts.com. Helium Inc. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- "Emergency Treatment for Leonardo da Vinci's Self-Portrait". news.universityproducts.com. Archival Products. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

Sources

- Bambach, Carmen C., ed. (2003). Leonardo da Vinci: Master Draftsman. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-1588390332.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chapman, Hugo; Faietti, Marzia (2010). Fra Angelico to Leonardo: Italian Renaissance Drawings. London, England: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-2667-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Covi, Dario A. (2005). Andrea del Verrocchio: Life and Work. Arte e archeologia: Studi e documenti. Florence, Italy: Leo S. Olschki Editore. ISBN 978-8822254207.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Delieuvin, Vincent, ed. (2012). Saint Anne: Leonardo da Vinci's Ultimate Masterpiece. Milan, Italy: Officina Libraria. ISBN 978-8897737025.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kemp, Martin (2006). Leonardo da Vinci: The Marvellous Works of Nature and Man. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-920778-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kemp, Martin (2019). Leonardo da Vinci: The 100 Milestones. New York City, New York: Sterling. ISBN 978-1454930426.

- Kemp, Martin (2011). Leonardo: Revised edition. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199583355.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marani, Pietro C. (2003). Leonardo da Vinci: The Complete Paintings. New York, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 978-0810991590.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pedretti, Carlo; Taglialagamba, Sara (2017). Leonardo da Vinci: the "Virgin of the rocks" in the Cheramy version: its history & critical fortune. Poggio a Caiano, Italy: CB edizioni. ISBN 978-8897644538.

- Pedretti, Carlo (1987). Leonardo Da Vinci: Drawings of Horses and Other Animals from the Royal Library at Windsor Castle. New York, New York: Johnson Reprint Corp. ISBN 978-0384452824.

- Pedretti, Carlo, ed. (1988). Achademia Leonardi Vinci:Journal of Leonardo Studies & Bibliography of Vinciana Vol. I–X. Villa La Loggia, Florence: Guinti. ISBN 978-0815001034.

- Pedretti, Carlo (2006). Leonardo: Art and Science. Surrey, England: Taj Books International. ISBN 978-1844060368.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rubin, Patricia Lee; Wright, Alison (1999). Renaissance Florence: The Art of the 1470s. London, England: National Gallery Publications. ISBN 978-1857092660.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shearman, John (1992). Only Connect: Art and the Spectator in the Italian Renaissance. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0691655413.

- Solari, Ernesto (2016). Leonardo da Vinci Horse and Rider Il "Monumento" a Charles d'Amboise. Milan: Colibri Edizioni. ISBN 978-88-97206-33-0.

- Syson, Luke; Keith, Larry; Galansino, Arturo; Mazzotta, Antoni; Nethersole, Scott; Rumberg, Per (2011). Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan (1st ed.). London, England: National Gallery. ISBN 978-1857094916.

- Zöllner, Frank (2019). Leonardo da Vinci: The Complete Paintings and Drawings (Anniversary ed.). Cologne, Germany: Taschen.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Works by Leonardo da Vinci. |

- Leonardo's works on Universal Leonardo

- Leonardo's works on Web Gallery of Art

- The Codex Arundel on the British Library's Digitised Manuscripts Website

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

_-_The_Holy_Infants.jpg)

_-_Christ_carrying_the_Cross.jpg)

.jpg)