Portrait of a Musician

Portrait of a Musician[n 2] (Italian: Ritratto di musico) is an unfinished portrait painting attributed to Italian Renaissance polymath Leonardo da Vinci, dated c. 1483–1487.[n 1] Painted in oil on walnut panel,[n 3] it is Leonardo's only known male portrait, whose identity is unknown, and has been closely debated among scholars. Until the 20th century it was thought to depict Ludovico Sforza, a Duke of Milan and employer of Leonardo. During a 1904–1905 restoration, the removal of overpainting revealed a hand holding sheet music, suggesting the sitter to be a musician.

| Portrait of a Musician | |

|---|---|

| Italian: Ritratto di musico | |

| |

| Artist | Leonardo da Vinci |

| Year | c. 1483–1487[n 1] (unfinished) |

| Medium | Oil on walnut panel |

| Dimensions | 44.7 cm × 32 cm (17.6 in × 13 in) |

| Location | Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan |

The portrait has attracted much debate as to it origin, as no there are not extant contemporary records of its commission. Its intimacy suggests it was commissioned by a private patron, or even a personal friend. Strong stylistic similarities to other works by Leonardo, especially the figure's face, have secured him at least a partial attribution. The hesitation for a full attribution is due to the stiff and rigid qualities of the figure's body, uncharacteristic of Leonardo. While the painting being unfinished may explain this, some scholars believe it was partially completed by a student of Leonardo's.

The portrait marks a dramatic shift from the typical profile portraits of Milan, taking inspiration from Antonello da Messina and perhaps Early Netherlandish painting. It shares many stylistic similarities with other paintings Leonardo made in Milan, such as Virgin of the Rocks and Lady with an Ermine, but the Portrait of a Musician is the only one to still reside there, where it has been housed at the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana since at least 1672. Over the centuries, many Italian musicians and politicians to have been proposed as the sitter. Franchinus Gaffurius was the most convincing suggestion throughout the 20th century, but scholarly opinion has shifted to Atalante Migliorotti, who has been the leading candidate throughout the 21st century. Other notable suggestions include Josquin des Prez and Gaspar van Weerbeke but there is no decisive evidence to confirm any claims.

Description

Portrait of a Musician represents a conscious and radical departure from the typical portraiture of Milan.[4] The Milanese audience was more artistically conservative than other parts of Italy,[5] and would have expected most, if not all, portraits to be in profile like those of Zanetto Bugatto, Vincenzo Foppa and Ambrogio Bergognone.[4] The Musician's three-quarter position was not without precedent as it was predated by many Netherlandish artists, who often maintained a black background as well.[6] Antonello da Messina who would also introduce similar black background and non-profile portraits in Venice and Sicily, with works like Portrait of a Man and Portrait of a Man with a Red Hat.[7] It is very possible that Leonardo was influenced by Messina's style and could have seen his work during Messina's brief visit to Milan in 1476,[8] or perhaps Leonardo saw the works in Venice on his 1486 visit to see his former teacher, Andrea del Verrocchio.[9]

Composition

This painting was made with oils on a rather small 44.7 × 32 cm (17.6 × 13 in) walnut wood panel.[9][n 3] Walnut wood was notably a medium which Leonardo favored,[10] recommended,[11] and was not commonly used by other Lombard artists of the time.[11] The work depicts a young man in a bust length, three-quarter position whose his right hand holds a folded musical score of some kind.[12] The man is viewed from slightly above.[13] With exception to the face and hair,[9] it is largely unfinished but in good overall condition overall with only the bottom right corner suffering some damage.[11][2] There is a small amount of retouching, especially towards the back of the head, and the colors seem to have faded over time.[11][14] It is reminiscent of his other portraits from his time in Milan, such as the Lady with an Ermine and La Belle Ferronnière, from their shared black background, while also differing in the angled, rather than profile view.[15]

The musician

The man has curly shoulder length hair, wears a red hat on his mostly finished face that intently stares at something outside the viewer's field of vision.[10] The stare is intensified by careful lighting that focuses the attention to his face,[3] especially his large glassy eyes.[13] He wears a tight white undershirt with an unfinished black doublet and only an underpainted brownish-orange stole.[2][15][16] The colors are faded, probably due to minor repainting and poor conservation. Technical examination of the work has revealed that the doublet was probably originally dark red and the stole bright yellow.[9]

The mouth hints at the start of a smile or suggests that perhaps the man is about to sing or has just sung.[17][18] A notable feature of the musician's face is the effect on his eyes from the light outside the frame.[19] The light causes both eyes to be dilated but the left eye to a far greater extent than the right, something that is not humanly possible.[8] Some defend Leonardo, claiming that this is simply for dramatic effect, so the viewer feels a sense of motion from the musician's left to right side of his face.[20] Museum curator Luke Syson notes that "The eyes are perhaps the most striking feature of the Musician, sight given primacy as the noblest sense and the most important tool of the painter".[18]

Musical score

The stiffly folded piece of paper is held in an odd and delicate manner and is at least one part of a musical score, with musical notes and letters written on it.[2] Due to the poor conservation of the lower part of the painting, the notes and letters are largely illegible.[2][3] This has not stopped some scholars from hypothesizing as to what the letters say, often using their interpretations to support their theory of the musician's identity.[21] The notes have offered little clarity into the painting,[12] other than strongly suggesting the subject to be a musician.[22] The notes are in mensural notation and therefore likely representative of polyphonic music.[16] Drawings from Royal Library of Windsor containing Leonardo's music notational style do not share a resemblance to the music in the painting.[12] This suggests that the music is not by him, which leaves the composer and the significance of the music, unknown.[12]

Background

Attribution

While once controversial, it is widely agreed by modern scholars that Portrait of a Musician is by Leonardo da Vinci.[23] Although no recording of the commission exists,[10] the attribution is based on a number of stylistic similarities to Leonardo's other works, notably the angel and St. Jerome's face from Virgin of the Rocks and Saint Jerome in the Wilderness.[17][24] The dark background of the portrait, a style popularized by Leonardo, furthers this attribution as it appears in later portraits from his time in Milan, such as Lady with an Ermine and La Belle Ferronnière.[23] The former painting in particular has showed many similarities in style from X-ray testing.[11] Other characteristics typical of Leonardo's style include the melancholic atmosphere, mouth that seems to have just closed or be about to open and curly hair,[9] reminiscent of Ginevra de' Benci.[17] The attribution is furthered by a comparison of the musician's eyes, which dialite to different degrees,[8] and a passage in Leonardo's notes:

The pupil [of the eye] dilates and contracts according to the brightness or darkness of the objects [in its sight]; and since it takes some time to dilate and contract, it cannot see immediately on going out of the light and into the shae, nor, in the same way, out of the sahe and into the light, and this very thing has already deceived me in the painting of an eye, and that is how I learned it.[8]

This suggests that Portrait of a Musician is representative of this observation by Leonardo.[18]

The past controversy over the painting's attribution had stemmed from the rigid and stoicness of the painting,[2] something largely uncharacteristic of Leonardo.[11] While some scholars explained this to be from the painting being unfinished, others proposed that the clothing and torso were done by a student of his, perhaps Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio or Giovanni Ambrogio de Predis.[11] However, art historian Pietro Marani notes that it is unlikely that Leonardo would have had assistants in the mid-1850s and even if he did, they would likely not be assisting on a portrait for an official or personal friend.[25] Despite Marani's points, there is still a substantial minority of scholars that disagree with a full attribution,[9] but it is almost universally agreed that if Leonardo did not create the whole painting, then he at least painted the face.[10]

Dating

Strong stylistics similarities to Lady with an Ermine through X-ray testing[11] as well as the treatment of chiaroscuro in Virgin of the Rocks and sketches for a bronze horse sculpture make this painting datable to Leonardo's First Milanese period (c. 1482–99).[24] However, the earliest date given by scholars is 1483.[2] Modern scholars have also noted that it was likely not made much later than 1487,[25] since the work has been seen to lack some of the refinements and realism of his later works, such as Lady with an Ermine;[22] Leonardo would engage in a study of human anatomy, especially the skull, in the late 1480s.[9] The painting is therefore safe to date to the mid–1480s,[22] usually 1483–1487.[n 1]

History

This is Leonardo's only portrait to remain in Milan, and was catalogued by Pietro Paolo Bosca into the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in 1672.[9] It is possible that the work may have been given to the Ambrosiana as early as 1637 by Galeazzo Arconati but this is mostly speculative.[11] It was listed with a description of "with all elegance that might be expected of a ducal commission,"[n 4] which implies that the subject was thought to be Ludovico Sforza, an employer of Leonardo and the Duke of Milan at the time of the painting's creation.[14][9] The theory was that it was a counterpart to the Portrait of a Lady, now attributed to Giovanni Ambrogio de Predis, but at the time was thought to be a Leonardo portrait of Beatrice d'Este, Ludovico's wife.[26] In 1686, an inventory listed it to be by Bernardino Luini,[11] but this was soon crossed out and corrected to "or rather by Leonardo."[9] In 1796, Portrait of a Musician hung in the Louvre, after being taken by Napoleon Bonaparte; it was attributed to Bernardino Luini.[9] However, after its return to Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan in 1815, it was relisted to be by Leonardo.[27]

These assumptions of the subject as Ludovico was taken without question until a 1904–1905 restoration by Luigi Cavenaghi and Antonio Grandi removed a layer of black paint and revealed a hand holding a musical score.[14] This identification led most scholars to believe the subject as a musician, especially those in Milan at the time,[22] and not Ludovico.[28] Since this discovery, numerous candidates have been proposed as the sitter.[29]

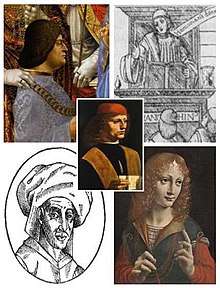

Identity of the sitter

The sitter is widely accepted as a musician since a 1904–1905 restoration removed a layer of black paint and revealed a hand holding a musical score.[26][28] While the sitter's identity is uncertain, he may appear in other works. Scholars at the National Gallery have suggested that Francesco Napoletano's Portrait of a Youth in Profile and Leonardo's drawing of a Bust of a Youth in Profile depict the same person.[30] Various candidates, including the idea that the subject is anonymous,[29] have been proposed but without firm evidence.[11][31]

Franchinus Gaffurius

The leading candidate in the 20th century, as suggested by Luca Beltrami in 1906, was Franchinus Gaffurius, a priest, the leading music theorist in Milan,[2][4] court musician for Ludovico Sforza and maestro di cappella of Milan Cathedral.[19] Gaffurius and Leonardo were known to have been friends, both entering the Duke's service only a year or two apart from each other. In fact, Gaffurius' celebrated 1496 music treatise, Practica Musica, contains various woodcuts by Leonardo.[32] Additionally, the letters "Cant" and "Ang" have been deciphered on the sheet music which could be an abbreviation for "Cantum Angelicum." This may be to be in reference to Angelicum ac divinum opus, a music treatise by Gaffurius.[26]

The theory has been disproven because iconographic evidence does not match Gaffurius to the man in Portrait of a Musician.[4] Kemp notes that the letter "Cant" and "Ang" could just as easily be "Cantore Angelico," meaning "angelic singer."[2] Also, the subject of the painting was not depicted in a clerical robe, which would have properly identified him as a priest, and the subject of the painting is a young man; Gaffurius would have been in his mid thirties at the time.[33][34]

Atalante Migliorotti

Since the publication of Marani's 2000 theory,[7] Atalante Migliorotti, a Tuscan musician, has been the most widely accepted identity of the musician.[19][12] In 1482, Migliarotti and Leonardo left Florence for Milan to serve in the court of Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan.[26] The two men were known to be friends,[15] and Leonardo is thought to have taught Migliarotti the lute[35] and lyre.[29] During the painting's conception, Migliarotti would have been in his late teens or early twenties, making him a fitting candidate to be the young man in the painting.[36] Additionally, in a 1482 inventory from the Codex Atlanticus[n 5] Leonardo listed "a portrait of Atalante with his face raised".[19][n 6] This has been thought of by many to have been a study or an early attempt to create Portrait of a Musician.[8][19] The intimate feel of the portrait makes a personal friend as the sitter even more likely.[2]

The only issue with the theory seems to be that the subject's face is not raised, as per the 1482 note.[19] However, Marani notes that while the musician's face is not raised in a literal sense, "the expression seems uplifted, suggesting a singer who has just raised his face from the sheet of music."[8] Therefore, since the widespread rejection of Franchinus Gaffurius as the leading candidate,[22] Migliarotti is now considered the most likely subject.[12][33]

Josquin des Prez

In 1972 the French singer and composer Josquin des Prez was suggested as the subject by the Belgian musicologist, Suzanne Clercx-Lejeune.[37] Josquin worked in the service of the Sforza family during various periods of the 1480s,[38] consequently working at the same time as Leonardo.[39] Clercx-Lejeune proposed that the words on the musical score are the abbreviations "Cont," "Cantuz," and "A Z" of the words "Contratenor," "Cantuz" and "Altuz".[4] She claimed that this meant they were associated with a song with a descending melodic line, such as masses, motets and songs by Josquin.[36][n 7]

This theory has been strongly discredited as the notation in the painting is largely illegible, and many composers of the time were writing music in this manner.[36] Additionally, like Gaffurius, other portraits do not show a resemblance[18] and Josquin was a priest in his mid 30s, so therefore unlikely to be the subject of this painting.[37]

Gaspar van Weerbeke

Art historian Laure Fagnart suggested in 2019 that the sitter is Gaspar van Weerbeke, a Netherlandish composer and singer. Gaspar worked for the Sforza family at the same time as Leonardo, and they likely knew each other due to their shared employer. This theory cites letters from Galeazzo Maria Sforza to Gotardo Panigarola concerning the attire of musicians for the court, with one stating, "Gotardo. To Gaspar, our singer, we would like to give a dark velvet robe, such as you have given to the Abbot [Antonio Guinati] and to Cordier, both of them also our singers". As Fagnart points out, this letter is too vague to definitely link Gaspar to the portrait, additionally, Gaspar runs into the same issue as Josquin and Gaffurius, as he would have also been in his 30s and probably too old to be the young man in the painting.[31]

Others

Gian Galeazzo Sforza has been suggested as the sitter, since Leonardo lived with him while in Milan and the vague original description of the portrait being of the Duke of Milan could refer to Galeazzo. Syson notes that this identification would be particularly meaningful as Galeazzo was the rightful heir to throne before Ludovico took power. Not only is there no direct evidence to support this, but the uncovering of the musical score makes this very unlikely as Galéas de Saint-Séverin was not known to be a musician.[18] Francesco Canova da Milano, an Italian lutenist and composer, has been suggested as the subject since he was an important musician also working in Milan when Leonardo was there, however, there is no strong evidence to support this claim.[40] Dutch illustrator Siegfried Woldhek proposed that Portrait of a Musician is one of three self portraits by Leonardo,[41] although this theory is considered highly improbable.[29]

Interpretation

Given the lack of contemporary records, scholars have proposed various theories as to the purpose of the painting. A number believe that the tension in the subject's face is intense because he is in the process of performing.[17][36] The painting has also been seen to be a representation of Leonardo's self proclaimed ideology of the superiority of painting over other art forms like poetry, sculpture and music.[18] Leonardo famously declared in the beginning of his uncompleted Libro de pittura:

How Music Ought to be Called the Sister and Junior to Painting. Music is to be regarded none other than the sitter of painting since it is subject to hearing, a sense second to the eye, and since it composes harmony from the conjunction of its proportional parts operating at the same time. [These parts] are constrained to arise and to die in one or more harmonic tempos which surround a proportionality by its members; such a harmony is composed not differently from the circumferential lines which generate human beauty by its [respective] members. Yet painting excels and rules over music, because it does not immediately die after its creation the way unfortunately music does. To the contrary, painting stays in existence, and will show you as being alive what is, in fact, on a single surface.

These words seemingly disapprove of music for its ephemeral nature, and positions painting as having a materiel, permanent physical quality.[18] This theory suggests that the sadness in the young man's eyes is due to this proposed idea that music simply disappears after a finished performance.[42]

Another interpretation is that Leonardo was simply moved to depict the a young man's beauty and curly hair. But more likely, due to the odd and seemingly intimate aesthetic of the painting, it was made as a personal gift for a close friend.[2][19] This would fit with a lot of the proposed subjects, especially Atalante Migliorotti, a close friend of Leonardo's and one likely not financially able to commission a portrait himself.[36]

Notes

- Scholars date the painting to 1483–1487:

- Kemp 2019, p. 47: c. 1483–1486

- Marani 2003, p. 339: c. 1485

- Syson 2011, p. 95: c. 1486–1487

- Zöllner 2019, p. 225: c. 1485

- Occasionally referred to as Portrait of Young Man,[1] Portrait of a Man with a Sheet of Music[2] or The Musician.[3]

- Zöllner 2019, p. 225: Claims that the work is of Tempera and oil, but this is not corroborated in Marani 2003, p. 339 or Syson 2011, p. 95.

- Alternatively translated as: "the face of the Duke of Milan, with such elegance, that perhaps the living Duke would have wanted it for himself".[14]

- Folio 888 recto (ex 324 recto) to be exact.[36]

- Alternatively translated as: "a portrait of Atalante with his upturned face".[21] or "a head portrayed from Atalante who raises his face".[2]

- An example is Josquin's motet Illibata Dei Virgo nutrix.[36]

References

- Zöllner 2015, pp. 47–48.

- Kemp 2019, p. 47.

- Brown 1983, p. 105.

- Marani 2003, p. 164.

- Syson 2011, p. 85.

- Syson 2011, p. 86.

- Marani 2003, pp. 164–165.

- Marani 2003, p. 165.

- Syson 2011, p. 95.

- Isaacson 2017, p. 237.

- Zöllner 2019, p. 225.

- Bambach 2012, p. 83.

- Pedretti 2006, p. 62.

- Fagnart 2019, p. 74.

- Palmer 2018, p. 122.

- Fagnart 2019, p. 73.

- Pedretti 1982, p. 68.

- Syson 2011, p. 97.

- Isaacson 2017, p. 238.

- Isaacson 2017, p. 239.

- Fagnart 2019, pp. 75–76.

- Syson 2011, p. 96.

- Kemp 2003.

- Clark & Kemp 1989, p. 99.

- Marani 2003, p. 163.

- Silvestri 2009, p. 26.

- Boussel 1989, p. 87.

- Zöllner 2015, p. 45.

- Pooler 2014, p. 32.

- National Gallery 2011, p. 5.

- Fagnart 2019, p. 76.

- Pooler 2014, p. 31.

- Blackburn 2001.

- Pooler 2014, pp. 31–32.

- Harrán 2001.

- Fagnart 2019, p. 75.

- Macey et al 2001.

- Macey et al. 2001.

- Pinacoteca Ambrosiana.

- Wallace & Kemp.

- Woldhek 2008.

- Fagnart 2019, p. 77.

Sources

- Books

- Boussel, Patrice (1989). Leonardo da Vinci. Chartwell House. ISBN 978-1-5552-1103-5.

- Clark, Kenneth; Kemp, Martin (1989). Leonardo da Vinci: Revised Edition (2nd ed.). City of Westminster, London, England: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-1401-6982-9.

- Fagnart, Laure (2019). "Gaspar Depicted? Leonardo's Portrait of a Musician". In Lindmayr-Brandl, Andrea; Kolb, Paul (eds.). Gaspar van Weerbeke: New Perspectives on his Life and Music. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols. pp. 73–77. doi:10.1484/M.EM-EB.4.2019026. ISBN 978-2-5035-8454-6.

- Isaacson, Walter (2017). Leonardo da Vinci (1st ed.). New York City, New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-5011-3915-4.

- Kemp, Martin (2019). Leonardo da Vinci: The 100 Milestones. New York City, New York: Sterling. ISBN 978-1-4549-304-26.

- Marani, Pietro C. (2003) [2000]. Leonardo da Vinci: The Complete Paintings (1st ed.). New York City, New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-3581-5.

- Palmer, Allison Lee (2018). Leonardo da Vinci: A Reference Guide to His Life and Works (Significant Figures in World History). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-1977-8.

- Pedretti, Carlo (1982). Leonardo, a study in chronology and style (1st ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Johnson Reprint Corp. ISBN 978-0-3844-5281-7.

- Pedretti, Carlo (2006). Leonardo da Vinci. Surrey, England: Taj Books International. ISBN 978-1-8440-6036-8.

- Pooler, Richard Shaw (2014). Leonardo Da Vinci's Treatise of Painting. The Story of The World's Greatest Treatise on Painting – Its Origins, History, Content, And Influence (1st ed.). Wilmington, Delaware: Vernon Press. ISBN 978-1-6227-3017-9.

- Silvestri, Paolo De (2009). Leonardo. Roma, Italy: ATS Italia. ISBN 978-8-8757-1873-2.

- Syson, Luke; Larry Keith; Arturo Galansino; Antoni Mazzotta; Scott Nethersole; Per Rumberg (2011). Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan (1st ed.). London, England: National Gallery. ISBN 978-1-8570-9491-6.

- Zöllner, Frank (2015). Leonardo (2nd ed.). Cologne, Germany: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8365-0215-3.

- Zöllner, Frank (2019). Leonardo da Vinci: The Complete Paintings and Drawings (Anniversary ed.). Cologne, Germany: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8365-7625-3.

- Journals and articles

- Blackburn, Bonnie J. (2001). "Gaffurius [Gafurius], Franchinus". Grove Music Online. London, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.10477. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Brown, David Alan (1983). "Leonardo and the Idealized Portrait in Milan". Arte Lombarda. 64 (4): 102–116. JSTOR 43105426.

- Harrán, Don (2001). "Frottola". In Chater, James (ed.). Grove Music Online. London, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.10313. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Kemp, Martin (2003). "Leonardo da Vinci". Grove Art Online. London, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T050401. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Macey, Patrick; Noble, Jeremy; Dean, Jeffrey; Reese, Gustave (2001). "Josquin (Lebloitte dit) des Prez". Grove Music Online. London, England: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.14497. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Online

- Bambach, Carmen C. (2012). ""Seeking the Universal Painter" (review of exhibition, Leonardo, Painter at the Court of Milan, National Gallery, London)". Apollo. Vol. 175 no. 595. London, England: Apollo Magazine. pp. 82–83.

- "Leonardo Da Vinci Painter at the Court of Milan" (PDF). London, England: The National Gallery. 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- "Portrait of a Musician Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519)". Milan, Italy: Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- Wallace, Marina; Kemp, Martin. "Portrait of a Musician". London, England: University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- Woldhek, Siegfried (February 2008). "Siegfried Woldhek shows how he found the true face of Leonardo". TED Conferences. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Portrait of a Musician. |