La Scapigliata

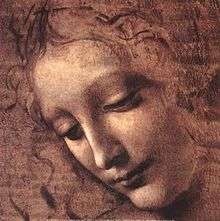

La Scapigliata (Medieval Italian: La Scapiliata;[n 1] Italian for 'The Lady with Dishevelled Hair') is an unfinished painting generally attributed to the Italian Renaissance polymath Leonardo da Vinci, dated c. 1506–1508. Painted in oil, earth, and white lead pigments on a poplar wood panel, the painting's attribution remains controversial, with several experts attributing the work to a student of his. Irrespective of the artist's identity, the painting has been admired for its captivating beauty, mysterious demeanor, and mastery of sfumato.

| La Scapigliata | |

|---|---|

| English: The Lady with Dishevelled Hair | |

| |

| Artist | Leonardo da Vinci |

| Year | c. 1506–1508 (unfinished) |

| Medium | Oil, earth, and white lead pigments on poplar wood panel |

| Dimensions | 24.7 cm × 21 cm (9.7 in × 8.3 in) |

| Location | Galleria nazionale di Parma, Parma |

Little is known about the painting for certain; information on its subject, date, history and purpose is mostly speculative. The painting portrays an unknown woman gazing downward while her hair fills the frame behind her. No theory of the subject has been widely accepted, but many have been proposed, such as the painting being a sketch for an uncompleted painting of Saint Anne, or perhaps being a study for the London version of Virgin of the Rocks or the lost Leda and the Swan painting.

Records of the painting may exist as early as 1531 but certainly by 1826, where it was part of the sale of Gaetano Callani's collection and was sold to the Galleria nazionale di Parma in 1839, where it has been housed ever since. While the opinions of scholars still remain divisive, the majority attribute the work to Leonardo and it has been listed as such in various major Leonardo exhibitions.

Description

Name

The painting has no formal name but is usually known by the nickname La Scapigliata (English: The Lady with Dishevelled Hair), in reference to the tousled and waving hair of the subject.[2] It has been known by various names in addition to La Scapigliata, including Head of a Woman,[3] Head of a Young Woman,[4] Head of a Girl,[2] Head of a Young Girl,[5] Head and Shoulders of a Woman,[6] Portrait of a Maiden[7] and Female Head.[8]

The painting

The work's true nature is unknown and it has been variously referred to as a sketch, a drawing or a painting.[9] Due to the use of paint, it is correctly described as a painting,[1] but scholars continue to discuss its sketch and drawing like qualities, often liking it to The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Saint John the Baptist.[10] Art historian Carmen Bambach compares the painting to two other unfinished works by Leonardo, the Adoration of the Magi and Saint Jerome in the Wilderness, suggesting that it should be described as a "brush drawing", or "painted sketch".[6][4]

The painting is done on a small 24.7 × 21 cm (9.7 × 8.3 in) poplar wood panel with oil, earth, and white lead pigments.[11] It portrays the unfinished outline of a young woman whose face gently gazes downward while her loosely drawn disheveled hair waves in the air behind her.[6] The woman's eyes are half-closed and completely ignoring of the outside world and viewer, while her mouth is slightly shaped into an ambiguous smile, evocative of the Mona Lisa.[2] Other than her face, which takes up most of the painting, the rest of the painting is barely even sketched in, with a primed, but not painted background.[3] The differences in the face and rest of the painting are effectively blended by a mastery of sfumato.[2] The appeal in this contrast of the unfinished and finished parts has provoked much speculation that the painting is not incomplete, and was left in an unfinished aesthetic on purpose.[6][9]

The subject of the painting is unknown and no theory has proved convincing to modern scholars.[1] One theory is that the painting is a study for Leonardo's lost painting of Leda and the Swan, but this is discredited by existing copies of the painting showing Lena with hair more elaborate than that of the woman in La Scapigliata.[6] Other unconfirmed claims are that the painting was another sketch, like The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Saint John the Baptist, for a painting of Saint Anne that was never completed, or a study for the London version of The Virgin of the Rocks.[1] Some scholars suggest that the subject of the painting is simply anonymous.[2]

Background

Attribution and date

It is generally agreed by modern scholars that La Scapigliata is by Leonardo da Vinci.[4] The attribution is not as widely accepted as other debated Leonardo paintings, like his Ginevra de' Benci, Portrait of a Musician, Lady with an Ermine and Saint John the Baptist and is often ignored by art historians, with many refraining from even commenting on it.[12][13] Some leading scholars, namely, Martin Kemp and Frank Zöllner leave the work out of their catalogues of Leonardo's paintings,[14] while others, such as museum curator Luke Syson,[15] propose the painting to be by a student of Leonardo's.[3]

The controversy around the painting's attribution is nothing new, in 1896, the current director of the gallery, Corrado Ricci, claimed the painting was not by Leonardo and rather a forgery by Gaetano Callani, a past owner of the painting.[1][9] However, Ricci's claim only caused enough doubt for the work to end up being catalogued as by the "school of Leonardo".[9] This claim was soon challenged by art historian, Adolfo Venturi, who adementally claimed that the work was by Leonardo, and discovered much historical evidence linking it the House of Gonzaga.[1] The authenticity of the painting to be by Leonardo was further advocated by Carlo Pedretti, who connected the painting to Isabella d'Este, a known patron of Leonardo.[1][10] The majority of the scholarly community has since accepted the work to be an autograph Leonardo,[16] but some modern critics continue to question the authenticity.[3] Art historian, Jacques Franck, doubts the painting to be by Leonardo based on the irregular proportions and strangely shaped skull of the subject. Franck further proposes that the painting is by Leonardo's student, Giovanni Boltraffio, due to the similarly to Boltraffio's Heads of the Virgin and Child, kept in the Chatsworth House.[17] Bernardino Luini, another student of Leonardo, has been suggested as the artist, because of the similarity of his depictions of females to La Scapigliata.[1] All major exhibitions where the painting has appeared including in the Louvre (2003), Milan (2014–2015), New York (2016), Paris (2016), Naples (2018) and the Louvre (2019–2020), have displayed the painting as being by Leonardo.[18]

The painted is usually dated c. 1506–1508 based on stylistic similarities to other works by Leonardo, namely The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Saint John the Baptist and the London Virgin of the Rocks.[19][20][21] Recently in 2016, Bambach, dated the painting to c. 1500–1505 since she believes Leonardo was commissioned by Agostino Vespucci at this time.[6]

History

No records of a commission survive for the painting, but its intimacy suggests it may have been for a private patron.[6] Bambach suggests that the painting was commissioned by Florentian official, Agostino Vespucci, and cites his letter that mentions Leonardo and describes the appeal and beauty of the unfinished bust of Venus famous ancient Greek painter, Apelles.[6] Bambach believes that La Scapigliata may be the result of Vespucci commissioning Leonardo to make a work along the same lines.[22] A more widely accepted theory is that the work was commissioned by a known patron of Leonardo and member of the Gonzaga family, Isabella d'Este, who had asked Leonardo for a painting of a Madonna for her private studio in 1501.[18] Isabella d'Este probably gifted the painting to her son Federico II Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua for his wedding with Margaret Paleologa.[23] This is evidenced by a 1531 letter from the secretary of the Mantuan Gonzaga family, Ippolito Calandra, who suggests that a painting with very similar features to La Scapigliata be hung in the bedroom of Federico II and Margaret Paleologa.[10] A 1531 inventory of Gonzaga family's art collection in the ducal palace also records a painting that could be La Scapigliata.[24] Another inventory from 1627 almost certainly refers La Scapigliata and is likely the origin of the nickname since the record describes it as: "A painting depicts the head of a disheveled woman... by Leonardo da Vinci."[24][9] This record implies that it was not sold in a large 1626–1627 sale of paintings from the Gonzaga family to Charles I of England. However, it was likely stolen 3 years later by an imperial army of 36,000 Landsknecht mercenaries, under the pay Ferdinand II, in their 1630–1631 sacking of Mantua.[18]

The next and first certain record of the painting is in 1826, when Francesco Callani offered the collection his father, the Parmesan artist Gaetano Callani, for sale to the Gallery in the Academy of Fine Arts of Parma.[9][24] In a list of the works in the collection for the director of the of the Gallery, Paolo Toschi, La Scapigliata appears listed as "A head of Madonna painted in chiaroscuro."[1] The sale implies that it entered the collection of Gaetano Callani at some point, probably during his 1773–1778 stay in Milan, but other than being in Milan, there is no information on the painting's whereabouts before then.[18][9] The sale took place in 1839, but La Scapigliata itself entered the gallery of Palatine Gallery of Parma (Now Galleria nazionale di Parma), where it was listed as "The head of Leonardo da Vinci" and described by Toschi as "a very rare work to find today.[9][2] It has been housed in the National Gallery of Parma ever since.[24]

Interpretation

Pietro C. Marani[18]

The ambiguity in the work's 'painted-drawing' demeanor, has caused many scholars to propose theories on the work's purpose and meaning.[2] The contrast between her sculptural and detailed face with the fragmentary hair, shoulders and neck has been said to evoke a similar contrast between intensity and freedom.[6] In fact, some have taken this contrast as a feminist representation of powerful but elegant femininity.[18]

When attributed to Leonardo, the work is often seen as the apex of Leonardo-esque sfumato.[21] In particular, art historian Alexander Nagel notes the attentive detail to masterful shadowing and lighting.[25] Nagel further compares La Scapigliata with the head studies Leonardo's teacher, Andrea del Verrocchio, noting the similarities in attention to shading techniques.[25] Nagel further explains that both Verrocchio's studies of female heads and Leonardo's La Scapigliata seem to "'know' that the edge of the panel exists. Nagel concludes that

"In Leonardo's work, shadow is investigated to the point where it assumes an entirely new role, Shadows no longer "belong" to the form but are treated as variations of a more general visual phenomenon, subject to the laws that govern all visibility. They behave as gradual modulations within a continuous range extending between 'the beginnings and the ends of shadow,' that is, from light to absolute darkness. The shadow against the right cheek ('outside the form') belongs to the same system as the shadows under the chin, on the cheek, or around the eyes; under different conditions, they might unite to swallow the entire face."[25]

While it is still uncertain how much access Leonardo would have had to Pliny the Elder's Natural History, in 2016 Bambach suggested that La Scapigliata may have been inspired by an anecdote from Natural History. Pliny refers to an unfinished painting of Venus of Cos by the famous ancient Greek painter, Apelles, that was admired even while unfinished. Bambach cites a note from Agostino Vespucci that mentions both Leonardo and this story and claims that Leonardo was inspired to achieve a painting like Apelles that was admired even while unfinished.[22]

Notes

- While both La Scapigliata and La Scapiliata are Italian spellings, the former is older and not as used as often as the latter. However, it is occasionally used, such as on the website of the Galleria nazionale di Parma, the museum that houses the painting.[1]

References

- Galleria Nazionale di Parma – New Website.

- Galleria Nazionale di Parma – Old Website.

- Palmer 2018, p. 70.

- Bambach 2003, p. 97.

- Marani 2003, p. 145.

- Baum et al 2016, p. 297.

- Pedretti 2006, p. 70.

- Fried 2010, p. 74.

- European News Agency.

- Vezzosi 2019, p. 275.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Marani 2019, pp. 338–340.

- Boussel 1989, p. 87.

- Zöllner 2019, pp. 212–251.

- Syson et al 2011, p. 198.

- Marani 2019, p. 340.

- Manca 2020.

- La fortuna della Scapiliata di Leonardo da Vinci.

- Marani 2003, p. 145, 340.

- Vezzosi 2019, p. 58.

- Fried 2010, p. 70.

- Baum et al 2016, p. 37.

- Marani 2019, p. 423.

- Marani 2003, p. 340.

- Nagel 1993, p. 11.

Sources

- Books

- Bambach, Carmen C., ed. (2003). Leonardo da Vinci, Master Draftsman. New York City, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780300098785.

- Baum, Kelly; Bayer, Andrea; Wagstaff, Sheena (2016). Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible. New York City, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9781588395863.

- Boussel, Patrice (1989). Leonardo da Vinci. Chartwell House. ISBN 9781555211035.

- Fried, Michael (2010). The Moment of Caravaggio. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691147017.

- Marani, Pietro C. (2003) [2000]. Leonardo da Vinci: The Complete Paintings (1st ed.). New York City, New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0810935815.

- Marani, Pietro C. (2019). "Tête de jeune femme". In Delieuvin, Vincent; Frank, Louis (eds.). Léonard de Vinci (in French). Louvre, Paris: HAZAN. pp. 423–424. ISBN 978-2754111232.

- Palmer, Allison Lee (2018). Leonardo da Vinci: A Reference Guide to His Life and Works (Significant Figures in World History). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781538119778.

- Pedretti, Carlo (2006). Leonardo: Art and Science. Surrey, England: Taj Books International. ISBN 978-1844060368.

- Syson, Luke; Keith, Larry; Galansino, Arturo; Mazzotta, Antoni; Nethersole, Scott; Rumberg, Per (2011). Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan (1st ed.). London, England: National Gallery. ISBN 978-1857094916.

- Vezzosi, Alessandro (2019). Léonard de Vinci: Tout l'œuvre peint, un nouveau regard. Translated by Temperini, Renaud. Paris: MARTINIERE BL. ISBN 978-2732490878.

- Zöllner, Frank (2019). Leonardo da Vinci: The Complete Paintings and Drawings (Anniversary ed.). Cologne, Germany: Taschen. ISBN 978-3836576253.

- Articles

- Nagel, Alexander (1993). "Leonardo and sfumato". Anthropology and Aesthetics. 24: 7–20. JSTOR 20166875.

- Online

- "Head of a Woman (La Scapigliata)". New York City, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- "La fortuna della Scapiliata di Leonardo da Vinci" (in Italian). Parma, Italy: Galleria nazionale di Parma. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020.

- "La Scapigliata" (in Italian). Parma, Italy: Galleria Nazionale di Parma. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020.

- "Leonardo's The Head of a Woman in Naples". European News Agency.

- Manca, Isabelle (January 2020). "Un expert réfute l'attribution de La Scapigliata à Léonard" (in French). Le Journal des Arts.

- "Testa di fanciulla, detta "La scapiliata"" (in Italian). Parma, Italy: Galleria Nazionale di Parma.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scapigliata. |