Salvator Mundi (Leonardo)

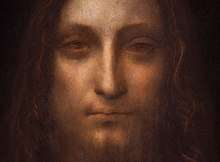

Salvator Mundi is a painting by Italian Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci dated to c. 1500.[2][3] Long thought to be a copy of a lost original veiled with overpainting, it was rediscovered, restored, and included in a major Leonardo exhibition at the National Gallery, London, in 2011–12.[4] Although most leading scholars have considered it to be an original work by Leonardo,[5] this attribution has been disputed by other specialists, some of whom posit that he only contributed certain elements.[6]

| Salvator Mundi | |

|---|---|

| English: Savior of the World | |

| |

| Artist | Leonardo da Vinci |

| Year | c. 1500 |

| Type | Oil on walnut panel |

| Dimensions | 45.4 cm × 65.6 cm (25.8 in × 19.2 in) |

| Condition | Restored |

| Owner | Acquired by Abu Dhabi's Department of Culture and Tourism for Louvre Abu Dhabi. Currently owned by Mohammad bin Salman[1] |

The painting depicts Jesus in Renaissance dress, making the sign of the cross with his right hand, while holding a transparent, non-refracting crystal orb in his left, signaling his role as Salvator Mundi (Latin for 'Savior of the World') and representing the 'celestial sphere' of the heavens.[7][8] Around 20 other variations of the work are known, by students and followers of Leonardo.[9] Preparatory chalk and ink drawings of the drapery by Leonardo are held in the British Royal Collection.

It is one of fewer than 20 known works by Leonardo, and was the only one to remain in a private collection. It was sold at auction for $450.3 million on 15 November 2017 by Christie's in New York to Prince Badr bin Abdullah, setting a new record for most expensive painting ever sold at public auction.[10] Prince Badr allegedly made the purchase on behalf of Abu Dhabi's Department of Culture and Tourism,[11][12] but it has since been posited that he may have been a stand-in bidder for his close ally and Saudi Arabian crown prince Mohammed bin Salman.[13] This follows late-2017 reports that the painting would be put on display at the Louvre Abu Dhabi[14][15] and the unexplained cancellation of its scheduled September 2018 unveiling.[16] The current location of the painting has been reported as unknown,[13] but a June 2019 report stated that it was being stored on bin Salman's luxury yacht, pending completion of a cultural center in Al-`Ula[17] and an October 2019 report indicated it may be in storage in Switzerland.[18]

History

%2C_Cook_Collection.jpg)

Leonardo da Vinci's Salvator Mundi may have been painted for Louis XII of France and his consort, Anne of Brittany.[2] It was probably commissioned around 1500, shortly after Louis conquered the Duchy of Milan and took control of Genoa in the Second Italian War. Leonardo himself moved from Milan to Florence in 1500.[19][20] Various copies of the painting were made by followers of Leonardo including his pupil Salaì (1511). Some versions differ significantly from the original, with a few, including one by his pupil Marco d'Oggiono (c. 1500) and another by Salaì[lower-alpha 1] depicting a more youthful subject.[lower-alpha 2]

Leonardo's painting seems to have been at James Hamilton's Chelsea Manor in London from 1638 to 1641. After participating in the English Civil War, Hamilton was executed on 9 March 1649 and some of his possessions were taken to the Netherlands to be sold.[23] Bohemian artist Wenceslaus Hollar could have made his engraved copy, dated 1650, in Antwerp at that time.[19][lower-alpha 3] It was also recorded in Henrietta Maria's possession in 1649,[23][lower-alpha 4] the same year her husband Charles I was executed, on 30 January. The painting was included in an inventory of the Royal Collection,[lower-alpha 5] valued at £30, and Charles' possessions were put up for sale under the English Commonwealth. The painting was sold to a creditor in 1651, returned to Charles II after the English Restoration in 1660,[24] and included in an inventory of Charles' possessions at the Palace of Whitehall in 1666. It was inherited by James II, and may have remained with him until it passed to his mistress Catherine Sedley,[19] whose illegitimate daughter with James became the third wife of John Sheffield, Duke of Buckingham. The duke's illegitimate son, Sir Charles Herbert Sheffield, auctioned the painting in 1763[24] along with other artworks from Buckingham House when the building was sold to George III.

The painting was likely placed in a gilded frame in the 19th century, which it remained in until 2005.[26] It was bought by British collector Francis Cook in 1900 for his collection at Doughty House in Richmond. The painting had been damaged from previous restoration attempts and was attributed to Bernardino Luini, a follower of Leonardo.[24] Cook's great-grandson sold it at auction in 1958 for £45[8] as a work by Leonardo's pupil Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, whom the painting remained attributed to until 2011.[27]

Rediscovery and restoration

.jpg)

.jpg)

Salvator Mundi is one of Leonardo's most copied paintings, with about 12 known examples executed by his pupils and others. Leonardo's version was thought to have been lost after the mid-17th century.[29] In 1978, Joanne Snow-Smith developed a compelling case that the supposed copy located in the Marquis Jean-Louis de Ganay Collection, Paris, was the lost original based on its similarity to Saint John the Baptist.[lower-alpha 7] Many art historians were convinced, as she was able to establish a direct historical connection between Leonardo da Vinci, the engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar and the painting in the Ganay collection.[30]

In 2005, a Salvator Mundi was presented and acquired at an auction for less than $10,000 (€8,450) by a consortium of art dealers that included Alexander Parrish and Robert Simon,[31] a specialist in Old Masters.[32][33] It was sold from the estate of Baton Rouge businessman Basil Clovis Hendry Sr.,[34] at the St. Charles Gallery auction house in New Orleans. It had been heavily overpainted so it looked like a copy, and was, before restoration, described as "a wreck, dark and gloomy".[35]

The consortium believed there was a possibility that this seemingly low-quality work might actually be the long-missing da Vinci original.[36] They commissioned Dianne Dwyer Modestini at New York University to oversee the restoration. She began by removing the overpainting with acetone, leading her to discover that at some point, a stepped area of unevenness near Christ's face had been shaved down with a sharp object, and also leveled with a mixture of gesso, paint and glue.[26] Using infrared photographs Simon had taken of the painting, Modestini discovered a pentimento (earlier draft) of the painting which had the blessing hand's thumb in a straight, rather than curved, position.[26] The discovery that Christ had two thumbs on his right hand was crucial. This pentimento (literally 'repent') showed the artist had a second thought about the positioning of the thumb. Such a second thought is considered evidence that this is not a copy but indeed an original, since copiers would have no doubts about composition.[15]

Modestini proceeded to have panel specialist Monica Griesbach chisel off a marouflaged wood panel which had been tunnelled through by worms, causing the painting to break into seven pieces. Griesbach reassembled the painting with adhesive and wood slivers.[26] In late 2006, Modestini began her restoration effort.[26] Art historian Martin Kemp was critical of the result: "Both thumbs" of the painting's raw state "are rather better than the one painted by Dianne."[15] The work was subsequently authenticated as a painting by Leonardo.[33][35] From November 2011 through February 2012, the painting was exhibited at the National Gallery as a work by Leonardo da Vinci, after authentication by that facility. In 2012, it was also authenticated by the Dallas Museum of Art.[31][33][37][lower-alpha 8]

In May 2013, the Swiss dealer Yves Bouvier purchased the painting for just over US$75 million (in a private sale brokered by Sotheby's, New York). The painting was then sold to Russian collector Dmitry Rybolovlev for US$127.5 million.[39][40][41] The price that Rybolovev paid was therefore significantly higher, well beyond the 2 percent commission Bouvier was supposed to receive, according to Dmitry Rybolovlev.[42][43][44] Consequently, this sale—along with several other sales Bouvier made to Rybolovlev—created a legal dispute between Rybolovlev and Bouvier,[45] as well as between the original dealers of the painting and Sotheby's. In 2016, the dealers sued Sotheby's for the difference of the sale, arguing they were shortchanged. The auction house has denied knowing that Rybolovlev was the intended buyer, and sought to dismiss the lawsuit.[46] In 2018, Rybolovlev also sued Sotheby's for $380 million, alleging the auction house knowingly participated in a defrauding scheme by Bouvier, in which the painting played a part.[47] Unearthed email exchanges between Bouvier and the auction house seem to confirm this, according to Rybolovlev's lawyers.[48]

It was exhibited in Hong Kong, London, San Francisco and New York in 2017, and then sold at auction at Christie's in New York on 15 November 2017 for $450,312,500,[lower-alpha 9] a new record price for an artwork (hammer price $400 million plus $50.3 million in fees).[52][53] The purchaser was identified as Saudi Arabian prince Badr bin Abdullah.[10][54] In December 2017, the Wall Street Journal reported that Prince Badr was an intermediary for Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.[55] However, Christie's confirmed that Prince Badr acted on behalf of Abu Dhabi's Department of Culture and Tourism for display at the Louvre Abu Dhabi.[11][56] In September 2018, the exhibition was indefinitely postponed,[57] and a January 2019 news report indicated that "no one knows where it is, and there are grave concerns for its physical safety."[31] Georgina Adam, editor at large of The Art Newspaper, dismissed these reports, stating that "We believe it's in storage in Geneva."[58] It was later reported to be on a luxury yacht belonging to bin Salman, sailing on the Red Sea as of June 2019.[59]

Just as the painting did not appear at the Abu Dhabi Louvre in 2018, it was not included in the Louvre's Paris exhibition of Leonardo works held from 24 October 2019 to 24 February 2020. A full 11 of the fewer than 20 paintings that da Vinci completed in his lifetime were displayed.[60][61]

Attribution

About a year into her restoration effort, Dianne Dwyer Modestini noted that color transitions in the subject's lips were "perfect" and that "no other artist could have done that." Upon studying the Mona Lisa for comparison, she concluded that "The artist who painted her was the same hand that had painted the Salvator Mundi."[26]

In 2006, National Gallery director Nicholas Penny wrote that he and some of his colleagues considered the work a Leonardo original, but that "some of us consider that there may be [parts] which are by the workshop."[26] Penny conducted a side-by-side study of the Salvator Mundi and Virgin of the Rocks in 2008. Martin Kemp later said of the meeting, "I left the studio thinking Leonardo must be heavily involved," and that "No one in the assembly was openly expressing doubt that Leonardo was responsible for the painting."[26] In a 2011 consensus decision facilitated by Penny, the attribution to Leonardo da Vinci was agreed upon unequivocally.[27][62] By July 2011, separate press release documents were issued by the owners' publicity representative and the National Gallery, officially announcing the "new discovery".[27][63]

Once it was cleaned and restored, the painting was compared with, and found superior to, twenty other versions of Salvator Mundi. It was exhibited by London's National Gallery during the Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan from November 2011 to February 2012.[19][35][64][65] Several features in the painting have led to the positive attribution: a number of pentimenti are evident, most notably the position of the right thumb. The sfumato effect of the face—evidently achieved in part by manipulating the paint using the heel of the hand—is typical of many Leonardo works.[66] The way the ringlets of hair and the knotwork across the stole have been handled is also seen as indicative of Leonardo's style. Furthermore, the pigments and the walnut panel upon which the work was executed are consistent with other Leonardo paintings.[67] Additionally, the hands in the painting are very detailed, something that Leonardo is known for: he would dissect the limbs of the deceased in order to study them and render body parts in an extremely lifelike manner.[68]

One of the world's leading Leonardo experts, Martin Kemp,[69][70] who helped authenticate the work, said that he knew immediately upon first viewing the restored painting that it was the work of Leonardo: "It had that kind of presence that Leonardos have ... that uncanny strangeness that the later Leonardo paintings manifest." Of the better-preserved parts, such as the hair, Kemp notes: "It's got that kind of uncanny vortex, as if the hair is a living, moving substance, or like water, which is what Leonardo said hair was like."[66] Kemp also states:

However skilled Leonardo's followers and imitators might have been, none of them reached out into such realms of "philosophical and subtle speculation". We cannot reasonably doubt that here, we are in the presence of the painter from Vinci.[71]

Walter Isaacson in his biography of Leonardo wrote that the orb that Christ is holding does not correspond to the way an orb would realistically look:[72]

In one respect, it is rendered with beautiful scientific precision, but Leonardo failed to paint the distortion that would occur when looking through a solid clear orb at objects that are not touching the orb. Solid glass or crystal, whether shaped like an orb or a lens, produces magnified, inverted, and reversed images. Instead, Leonardo painted the orb as if it were a hollow glass bubble that does not refract or distort the light passing through it.[73]

Isaacson believes that this was "a conscious decision on Leonardo's part",[74] and speculates that either Leonardo felt a more accurate portrayal would be distracting, or that "he was subtly trying to impart a miraculous quality to Christ and his orb."[73] Kemp, on the other hand, says that the doubled outline of the heel of the hand holding the sphere—which the restorer described as a pentimento—is an accurate rendering of the refraction produced by a calcite (or rock crystal) sphere.[66] Kemp notes that the double refraction is typical of the type produced by a transparent calcite sphere.[lower-alpha 10][66] Kemp further notes that the orb "sparkles with a series of internal inclusions (or pockets of air)"—evidence supporting its solid nature.[7]. More recently, the globe has been also interpreted as a magnifying instrument consisting of a vitreous globe filled with water.[75]

Other versions or copies of Salvator Mundi often portray a brass, solid spherical orb, terrestrial globe, or globus cruciger; occasionally, they appear to be made of translucent glass, or show landscapes within them. The orb in Leonardo's painting, Kemp says, has "an amazing series of glistening little apertures—they're like bubbles, but they're not round—painted very delicately, with just a touch of impasto, a touch of dark, and these little sort of glistening things, particularly around the part where you get the back reflections." These are the characteristic features of rock crystal, which Leonardo was an avid expert on. He had been asked to evaluate vases that Isabella d'Este[lower-alpha 11] had thought of purchasing, and greatly admired the properties of the mineral.[66]

Iconographically, the crystal sphere relates to the heavens. In Ptolemaic cosmology, the stars were embedded in a fixed celestial crystalline sphere (composed of aether), with the spherical Earth at the center of the universe. "So what you've got in the Salvator Mundi", Kemp states, "is really 'a savior of the cosmos', and this is a very Leonardesque transformation."[66]

Another aspect of Leonardo's painting Kemp studied was depth of field, or shallow focus. Christ's blessing hand appears to be in sharp focus, whereas his face—though altered or damaged to some extent—is in soft focus. Leonardo's Manuscript D of 1508–1509,[79] explored theories of vision, optics of the eye, and theories relating to shadow, light and color. In Salvator Mundi, the artist deliberately placed an emphasis on parts of the picture over others. Elements in the foreground are seen with a sense of focus, while elements further removed are barely in focus, such as the subject's face. Manuscript D shows Leonardo was investigating this particular phenomenon around the turn of the century. Combined, the intellectual aspects, optical aspects, and the use of semi-precious minerals, are distinctive of Leonardo's oeuvre.[66]

"There is extraordinary consensus it is by Leonardo," said the former co-chairman of old master paintings at Christie's, Nicholas Hall: "This is the most important old master painting to have been sold at auction in my lifetime."[81] Christie's lists the ways scholars confirmed the attribution to Leonardo da Vinci:

The reasons for the unusually uniform scholarly consensus that the painting is an autograph work by Leonardo are several, including the previously mentioned relationship of the painting to the two autograph preparatory drawings in Windsor Castle; its correspondence to the composition of the 'Salvator Mundi' documented in Wenceslaus Hollar's etching of 1650; and its manifest superiority to the more than 20 known painted versions of the composition.

Furthermore, the extraordinary quality of the picture, especially evident in its best-preserved areas, and its close adherence in style to Leonardo's known paintings from circa 1500, solidifies this consensus.[19][82]

According to Robert Simon, "Leonardo painted the Salvator Mundi with walnut oil rather than linseed oil, as all the other artists in that period did. ... In fact, he wrote about using walnut oil, as it was a new advanced technique."[83] Simon also says that ultraviolet imaging reveals that the restoration mostly accounts for darker areas of the painting; the rest is original paint.[84]

Author Ben Lewis, who disputes complete attribution to Leonardo, admits its possibility, owing to the originality of the face, which has "something modern about it."[84] Kemp says:

I don't rule out the possibility of studio participation. ... But I cannot define any areas that I would say are studio work.[85]

Partial attribution

Some respected experts on Renaissance art question the full attribution of the painting to Leonardo.[86][74][87] Jacques Franck, a Paris-based art historian and Leonardo specialist who has studied the Mona Lisa out of the frame multiple times, stated: "The composition doesn't come from Leonardo, he preferred twisted movement. It's a good studio work with a little Leonardo at best, and it's very damaged. It's been called 'the male Mona Lisa', but it doesn't look like it at all."[81]

Michael Daley, the director of ArtWatch UK, doubts the Salvator Mundi's authenticity and theorizes that it may be the prototype of a subject painted by Leonardo:[88][89] "This quest for an autograph prototype Leonardo painting might seem moot or vain: not only do the two drapery studies comprise the only accepted Leonardo material that might be associated with the group, but within the Leonardo literature there is no documentary record of the artist ever having been involved in such a painting project."[88]

Carmen Bambach, Italian Renaissance art specialist at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, questioned full attribution to Leonardo: "having studied and followed the picture during its conservation treatment, and seeing it in context in the National Gallery exhibition, much of the original painting surface may be by Boltraffio, but with passages done by Leonardo himself, namely Christ's proper right blessing hand, portions of the sleeve, his left hand and the crystal orb he holds."[90][91] In 2019, Dr. Bambach criticised Christie's for its claim that she was one of the experts who had attributed the painting to Leonardo. In her forthcoming book Leonardo da Vinci Rediscovered, she is even more specific, attributing most of the work to Boltraffio, "with only 'small retouchings' by the master himself".[6]

Matthew Landrus, an art historian at the University of Oxford agreed with the concept of parts of the painting being executed by Leonardo ("between 5 and 20%"), but attributes the painting to Leonardo's studio assistant Bernardino Luini, noting Luini's ability in painting gold tracery.[92]

Frank Zöllner, the author of the catalogue raisonné Leonardo da Vinci. The Complete Paintings and Drawings.[93] writes:

This attribution is controversial primarily on two grounds. Firstly, the badly damaged painting had to undergo very extensive restoration, which makes its original quality extremely difficult to assess. Secondly, the Salvator Mundi in its present state exhibits a strongly developed sfumato technique that corresponds more closely to the manner of a talented Leonardo pupil active in the 1520s than to the style of the master himself. The way in which the painting was placed on the market also gave rise to concern.[88][93][94]

Zöllner also explains that the quality of Salvator Mundi surpasses other known versions, however,

[it] also exhibits a number of weaknesses. The flesh tones of the blessing hand, for example, appear pallid and waxen as in a number of workshop paintings. Christ's ringlets also seem to me too schematic in their execution, the larger drapery folds too undifferentiated, especially on the right-hand side. ... It will probably only be possible to arrive at a more informed verdict on this question after the results of the painting's technical analyses have been published in full (Dalivalle/Kemp/Simon 2017).[88][93][95]

In Paris, the Louvre's request for Salvator Mundi to be exhibited in the 2019–20 Leonardo de Vinci exhibition[96] was reportedly met without response,[97] leading some to speculate that its non-presence was due to doubts over its full attribution to the artist.[98] Kemp disputes this reasoning, saying:

It's simply untrue ... because even if the Louvre was persuaded that there was studio participation in the picture, which would be feasible and not unknown after all, it wouldn't stop them from showing it. It's a major picture, an important thing. The story is sensationalized and inaccurate.[3]

Rejection of attribution

British art historian Charles Hope dismissed the attribution to Leonardo entirely in a 2020 analysis of the painting's quality and provenance. He doubted that Leonardo would have painted a work where the eyes were not level and the drapery undistorted by a crystal orb. He added, "The picture itself is a ruin, with the face much restored to make it reminiscent of the Mona Lisa." Hope condemned the National Gallery's involvement in Simon's "astute" marketing campaign.[99]

Reception

The rediscovered painting by Leonardo generated considerable interest within the media and general public amid its pre-auction viewings in Hong Kong, London, San Francisco and New York. Over 27,000 people saw the work in person before the auction: the highest number of pre-sale viewers for an individual work of art, according to Christie's.[86] Never before had Christie’s used an outside agency to advertise an artwork. Around 4,500 stood in line to preview the work in New York the weekend prior to the sale.[86]

Referred to as the "Last da Vinci", Salvator Mundi was the only known painting by Leonardo still in private hands. Fewer than twenty other known works by Leonardo are held in museums around the world, including the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper. The only work by Leonardo in North America, Ginevra de' Benci, is held at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.[86] The museum purchased Ginevra in 1967 for $5 million in a private sale (equivalent to approximately $36.4 million in 2017), a world record at the time. Salvator Mundi is the first painting by the artist to appear in a public sale for 100 years.[86]

Gallery

Copies

School of Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi (c. 1503), Museo Diocesano, Napoli, Naples (formerly Marquis Jean-Louis de Ganay Collection)

School of Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi (c. 1503), Museo Diocesano, Napoli, Naples (formerly Marquis Jean-Louis de Ganay Collection) Cesare da Sesto (1516–1517), contemporary copy, Wilanów Palace, Warsaw

Cesare da Sesto (1516–1517), contemporary copy, Wilanów Palace, Warsaw%2C_first_half_of_XVI_century%2C_canvas%2C_63_x_48_cm%2C_Worsey_Collection.jpg) Anonymous, Salvator Mundi (Cristo Redentore benedicente), first half of 16th century, Worsey Collection(?)

Anonymous, Salvator Mundi (Cristo Redentore benedicente), first half of 16th century, Worsey Collection(?) Giampietrino, Salvator Mundi, 16th century, Detroit Institute of Arts

Giampietrino, Salvator Mundi, 16th century, Detroit Institute of Arts.jpg) Wenceslaus Hollar engraving (1650), inscribed in Latin: "Leonardo da Vinci painted it, ... from the original ...",[lower-alpha 12] Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library[23]

Wenceslaus Hollar engraving (1650), inscribed in Latin: "Leonardo da Vinci painted it, ... from the original ...",[lower-alpha 12] Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library[23] Anonymous, Salvator Mundi, Sammlung Stark, Zurich

Anonymous, Salvator Mundi, Sammlung Stark, Zurich

Other versions

Lombard follower of Leonardo da Vinci (possibly Marco d'Oggiono), Sotheby's

Lombard follower of Leonardo da Vinci (possibly Marco d'Oggiono), Sotheby's

%2C_oil_on_poplar%2C_61.6_x_53_cm%2C_National_Gallery.jpg) Andrea Previtali, Salvator Mundi (1519), National Gallery, London

Andrea Previtali, Salvator Mundi (1519), National Gallery, London

.jpg) Fernando Yáñez de la Almedina, The Eucharistic Christ (c. 1525), oil on panel, 67.5 x 54.2 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid[101]

Fernando Yáñez de la Almedina, The Eucharistic Christ (c. 1525), oil on panel, 67.5 x 54.2 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid[101]%2C_c._1570%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_96_x_80_cm%2C_Hermitage_Museum.jpg)

_-_Christ_Blessing_('The_Saviour_of_the_World')_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Jerónimo de Bobadilla, Spanish, 17th century, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

Jerónimo de Bobadilla, Spanish, 17th century, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg Anonymous Flemish artist (c. 1750–1775), Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Anonymous Flemish artist (c. 1750–1775), Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Youthful Christ with globe

Salaì, Cristo giovanetto come Salvator Mundi, Museo Ideale Leonardo da Vinci

Salaì, Cristo giovanetto come Salvator Mundi, Museo Ideale Leonardo da Vinci%2C_First_half_of_XVI_century%2C_tempera%2C_wood%2C_50_x_39_cm%2C_Pushkin_Museum.jpg) Giampietrino, Salvator Mundi (Savior of the World), First half of 16th century, Pushkin Museum, Moscow

Giampietrino, Salvator Mundi (Savior of the World), First half of 16th century, Pushkin Museum, Moscow

References

Footnotes

- Titled Cristo giovanetto come Salvator Mundi[21]

- The Apostle John in Leonardo's The Last Supper is similarly depicted as feminine relative to Jesus.[22]

- He had also been in England from 1637 to 1646. He also may have simply copied a copy of Leonardo's painting.[24]

- Some scholars claim that she might have had the painting when she moved from France and married Charles I in 1625, but this does not explain it being in Hamilton's possession from 1638 to 1641[23]—although Hamilton may have simply possessed a different copy.[24]

- Some scholars speculate that this could have been a copy, such as the one by Giampietrino.[25]

- Fragmentation caused by removal of worm-eaten auxiliary panel[26]

- Criteria for the comparisons included style, color, material, technique, historical evidence, spectral analysis at the Louvre laboratory, and the possibility that the Ganay painting could have been copied by Hollar in Nantes, France.[30]

- The last Leonardo to be discovered was the Benois Madonna, found in 1909.[38]

- The highest price previously paid for an artwork at auction was for Pablo Picasso's Les Femmes d'Alger, which sold for $179.4 million in May 2015 at Christie's New York. Willem de Kooning's Interchange was sold privately by the David Geffen Foundation to hedge fund manager Kenneth C. Griffin in September 2015 for $300 million, formerly the highest known sale price for any artwork.[49][50][51]

- None of the copyists had likely noticed or reproduced this crystalline orb with a double refraction.

- One of several candidates proposed as a plausible subject of Leonardo's Mona Lisa,[76] who owned a portrait of her drawn by Leonardo[77]

- Leonardus da Vinci pinxit, Wenceslaus Hollar fecit Aqua forti, secundum originale, A°. 1650 [100]

Citations

- Kazakina, Katya (11 June 2019). "Da Vinci's $450 Million Masterpiece Is Kept on Saudi Prince's Yacht: Artnet". Bloomberg. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- "Salvator Mundi". Christie's. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- Kinsella, Eileen (12 June 2019). "'Debunking This Picture Became Fashionable': Leonardo da Vinci Scholar Martin Kemp on What the Public Doesn't Get About 'Salvator Mundi'". artnet news.

- Syson, Luke (2011). Stephenson, Johanna (ed.). Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan. London: National Gallery Company. p. 302. ISBN 9781857094916.

- Hartley-Parkinson, Richard (16 November 2017). "Leonardo Da Vinci portrait of Jesus Christ 'Salvator Mundi' sells for $450,000,000". Metro.

- Alberge, Dalya (2 June 2019). "Leonardo da Vinci expert declines to back Salvator Mundi as his painting". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

Dr Carmen Bambach believes the polymath likely only did small retouchings to the work

- Martin Kemp, Christ to Coke: How Image Becomes Icon, Oxford University Press (OPU), 2012, p. 37, ISBN 0199581118

- "Video: The Last da Vinci – Christie's". Christies.com. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/salvator-mundi-expert-uncovers-exciting-new-evidence, Leonardo's Salvator Mundi: expert uncovers ‘exciting’ new evidence

- David D. Kirkpatrick (6 December 2017). "Mystery Buyer of $450 Million 'Salvator Mundi' Was a Saudi Prince". New York Times. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Yara Bayoumy (8 December 2017). "Abu Dhabi to acquire Leonardo da Vinci's 'Salvator Mundi': Christie's". Retrieved 9 December 2017 – via Reuters.

- "Bought a $450M painting? In NY, don't worry about the tax". TheNewsTribune.com. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Kirkpatrick, David D. (30 March 2019). "A Leonardo Made a $450 Million Splash. Now There's No Sign of It". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- "Salvator Mundi". Abu Dhabi Department of Culture and Tourism on Twitter. 8 December 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- Jones, Jonathan (14 October 2018). "The Da Vinci mystery: why is his $450m masterpiece really being kept under wraps?". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- "Postponement of the unveiling of Salvator Mundi". Abu Dhabi Department of Culture and Tourism on Twitter. 2 September 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- Kazakina, Katya (10 June 2019). "Da Vinci's $450 Million Masterpiece Is Kept on Saudi Prince's Yacht: Artnet". Bloomberg. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- Doward, Jamie (13 October 2019). "The mystery of the missing Leonardo: where is Da Vinci's $450m Jesus?". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- "Salvator Mundi — The rediscovery of a masterpiece: Chronology, conservation, and authentication – Christie's'". Christies.com. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- correspondent, Mark Brown Arts (10 October 2017). "Only Leonardo da Vinci in private hands set to fetch £75m at auction". theguardian.com. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Barbatelli, Nicola; Melani, Margherita, eds. (10 January 2017). Leonardo a Donnaregina: I Salvator Mundi per Napoli (in Italian). CB Edizioni. p. 19. ISBN 9788897644385.

- Hodapp, Christopher; Von Kannon, Alice (2007). The Templar Code for Dummies (1st ed.). Wiley. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-470-12765-0.

- Cole, Alison (30 August 2018). "Leonardo's Salvator Mundi: expert uncovers 'exciting' new evidence". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- Daley, Michael (18 September 2018). "How the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi became a Leonardo-from-nowhere". Artwatch. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- Bailey, Martin (28 November 2018). "Would the 'royal' Salvator Mundi please stand up?". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- Shaer 2019.

- H. Niyazi, "Platonic receptacles, Leonardo and the Salvator Mundi", iconographic and provenance details of the painting, 18 July 2011

- St. Charles Gallery, 9–10 April 2005 auction catalog, New Orleans

- Lynn Picknett, Clive Prince, The Turin Shroud: How Da Vinci Fooled History, Simon and Schuster, 2007, p. 232, ISBN 0743292170

- Snow-Smith, Joanne. The Salvator Mundi of Leonardo Da Vinci, Arte Lombarda, no. 50, 1978, pp. 69–81. JSTOR

- Brean, Joseph (8 January 2019). "Where in the world is Salvator Mundi, the most expensive painting ever sold?". National Post. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- Lost Leonardo painting had tangled path to $450 million sale, LA Times, 16 November 2017

- Greene, Kerima (19 November 2017). "An art dealer explains how a da Vinci went from less than $200 to breaking the bank at $450M". CNBC. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- Michael Daley, Two developments in the no-show Louvre Abu Dhabi Leonardo Salvator Mundi saga, Artwatch UK, 11 October 2018

- Esterow, Milton (June 2011). "A Long Lost Leonardo". ARTnews. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- Isaacson, Walter. "How a Priceless da Vinci Masterwork Disappeared from View for Centuries". HISTORY. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Leonardo da Vinci, Painter at the Court of Milan, Leonardo da Vinci, Christ as Salvator Mundi, exhibition catalogue, n.71, National Gallery, 9 November 2011–5 February 2012" (PDF). NationalGallery.org.uk. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Travis M. Andrews and Fred Barbash, "Long-lost da Vinci painting fetches $450.3 million, an auction record for art", The Washington Post, 16 November 2017

- Reyburn, Scott (3 March 2014). "Recently Attributed Leonardo Painting Was Sold Privately for Over $75 Million". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Grosvenor, Bendor. "Salvator Mundi at heart of art fraud case". arthistory.com. Bendor Grosvenor. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- Clémençon, Gilles. Accusé d'escroquerie, le "roi des ports francs" Yves Bouvier riposte. RTS Info. 22 March 2015 (French)

- "Le marché de l'art en quête de transparence". La Tribune (in French). Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Sotheby's and Yves Bouvier Hit Back Against 'Salvator Mundi' Seller Rybolovlev in Ongoing Feud". artnet News. 21 November 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "Affaire Bouvier-Rybolovlev : de l'art et des milliards - EconomieMatin". www.economiematin.fr. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Sam Knight, "The Bouvier Affair, How an art-world insider made a fortune by being discreet" The New Yorker, 8 & 15 February 2016

- Kazakina, Katya (22 November 2016). "Dispute Over $127.5 Million Leonardo Painting Draws in Sotheby's". Bloomberg.

- Kazakina, Katya (3 October 2018). "Billionaire Slaps Sotheby's With $380 Million Lawsuit". Bloomberg.

- "Der Milliardär und sein teurer Da Vinci". Tages-Anzeiger (in German). ISSN 1422-9994. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Leonardo da Vinci painting 'Salvator Mundi' sold for record $450.3 million, Fox News, 16 November 2017

- "Da Vinci-maleri slår salgsrekord med pris på 2,8 milliarder". Bt.dk (in Danish). 16 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "'Leonardo da Vinci artwork' sells for record $450m". BBC News. 16 November 2017.

- "Post-War & Contemporary Art Evening Sale Lot 9B". Auction Catalog (Results). Christie's Auction House. 15 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Angel Au-Yeung, At Auction, Billionaire Sells Da Vinci Painting For A New World Record Price, Forbes.com, 15 November 2017

- Meixler, Eli (7 December 2017). "The Mystery Buyer of a $450 Million Leonardo da Vinci Painting Was a Saudi Prince". Fortune. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- Harris, Shane; Crow, Kelly; Said, Summer (7 December 2017). "Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Identified as Buyer of Record-Breaking da Vinci". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- "Embassy Statement on Art Work Purchase". The Embassy of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 8 December 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- "Louvre Abu Dhabi postpones display of Leonardo's Salvator Mundi". The Guardian. 8 January 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

Delayed unveiling of world’s most expensive painting adds to mystery shrouding its acquisition and authenticity

- Valle, Gaby Del (22 January 2019). "How a long-lost Leonardo da Vinci painting got dragged into a Trump-Russia conspiracy theory". Vox. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- Kazakina, Katya (10 June 2019). "Da Vinci's $450 Million Masterpiece Is Kept on Saudi Prince's Yacht: Artnet". Bloomberg. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- "Leonardo da Vinci's Unexamined Life as a Painter". The Atlantic. 1 December 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- "Louvre exhibit has most da Vinci paintings ever assembled". Aleteia. 1 December 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- "Leonardo da Vinci Painting Discovered" (PDF). Stacy Bolton Communications. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- "Bendor Grosvenor, Salvator Mundi, National Gallery statement, Art History News". arthistorynews.com. 13 July 2011. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- BBC News (12 July 2011). "Lost Leonardo Da Vinci painting to go on show". BBC. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- "Scholars authenticate a painting that was missing for centuries". En.99ys.com. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- Goldstein, Andrew M. (17 November 2011). "The Male "Mona Lisa"?: Art Historian Martin Kemp on Leonardo da Vinci's Mysterious "Salvator Mundi"". Blouin Artinfo.

- "Salvator Mundi – Newly Attributed da Vinci Painting". Arthistory.about.com. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- "Leonardo da Vinci's 'Male Mona Lisa' can be yours for just $100M (or more)". USA Today. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Fisher, Ian (9 February 2007). "A Real-Life Mystery: The Hunt for the Lost Leonardo". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Charney, Noah (6 November 2011). "The lost Leonardo". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Martin Kemp, Art history: Sight and salvation, Martin Kemp sifts the evidence that Leonardo da Vinci painted the newly emerged work Salvator Mundi, Nature, International Journal of Science, 479, 174–175, 10 November 2011. doi:10.1038/479174a, www.nature.com

- Alberge, Dalya (19 October 2017). "Mystery over Christ's orb in $100m Leonardo da Vinci painting". The Guardian.

- Isaacson, Walter (17 October 2017). Leonardo da Vinci. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781501139178.

- Kinsella, Eileen. "Doubters (Including Jerry Saltz) Love to Hate Leonardo's 'Salvator Mundi. Here's What the Experts Think". Artnet News. 14 November 2017

- Salvatelli, Luca; Constable, James (2020). "Riflessi (ed enigmi) in una sfera di vetro" [Reflections (and puzzles) in a glass sphere.]. Medioevo (279): 12–16.

- Zöllner, Frank: Leonardo da Vinci – Sämtliche Werke. Taschen Verlag (Cologne) 2007, p. 241 (effective catalogue raisonné); in German

- Bernier, Olivier (1983). The Renaissance Princes. Stonehenge Press. p. 61. ISBN 0867060859.

- "Réunion des Musées Nationaux-Grand Palais | Leonardo da Vinci, Manuscript D, 1508–09, Bibliothèque de l'Institut, Paris". photo.rmn.fr. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- "Paris Manuscript D". Universal Leonardo. University of the Arts, London. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- Leonardo da Vinci, A study of drapery for a Salvator Mundi, c. 1504–8 The Royal Collection

- Pogrebin, Robin; Reyburn, Scott (15 November 2017). "Leonardo da Vinci Painting Sells for $450.3 Million, Shattering Auction Highs". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Merrit Kennedy, Last Da Vinci Painting In Private Hands Will Be Auctioned Next Month, 11 October 2017)

- Brook Mason, What It Takes for a Leonardo da Vinci Painting to Be Deemed Universally Authentic, Architectural Digest, 22 May 2019

- Jacobson, Dana; Singh, Vidya. "Is "Salvator Mundi" a real Leonardo da Vinci painting?". CBS News. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- Holland, Oscar (16 June 2019). "The $450 million question: Where is the 'Salvator Mundi'?". CNN. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- Scott Teyburn, "Get in Line: The $100 Million da Vinci Is in Town", The New York Times, 13 November 2017

- Saltz, Jerry. "Christie’s Is Selling This Painting for $100 Million. They Say It's by Leonardo. I Have Doubts. Big Doubts." Vulture. 14 November 2017

- Michael Daley, Problems with the New York Leonardo Salvator Mundi Part I: Provenance and Presentation, ArtWatch UK, 14 November 2017

- Shamsian, Jacob (16 November 2017). "A lost Leonardo da Vinci painting just sold for a record $450 million — but critics have spotted an unusual flaw". Business Insider. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Some dispute authenticity of $450 million Leonardo da Vinci painting, Fox News, 17 November 2017

- Bambach, Carmen C. (2012). "Seeking the universal painter: Carmen C. Bambach appraises the National Gallery's once-in-a-lifetime exhibition dedicated to Leonardo da Vinci". Apollo Magazine.

- Alberge, Dalya (6 August 2018). "Leonardo scholar challenges attribution of $450m painting". the Guardian. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- Johannes Nathan, Frank Zöllner, Leonardo da Vinci. The Complete Paintings and Drawings, Taschen, 2017, ISBN 978-3-8365-2701-9

- Zöllner, Frank (2017). "Preface to the 2017 Edition" (PDF). Leonardo da Vinci. The Complete Paintings and Drawings, Köln 2017: 15–17.

- Zöllner, Frank (2017). "Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings, No. XXXIII, Salvator Mundi" (PDF). Leonardo da Vinci. The Complete Paintings and Drawings, Köln 2017: 440–445.

- Leonardo da Vinci, Louvre, Paris, 24 October 2019 – 24 February 2020

- Le «Salvator Mundi» de Leonard de Vinci, tableau le plus cher du monde, a disparu, Le Parisien and AFP, 29 April 2019

- Brown, Mark (26 May 2019). "The lost Leonardo? Louvre show ditches Salvator Mundi over authenticity doubts". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- Hope, Charles (22 December 2019). "Charles Hope | A Peece of Christ · LRB 22 December 2019". London Review of Books. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- Pennington, Richard (2002). A descriptive catalogue of the etched Work of Wenceslaus Hollar 1607–1677. Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780521529488.

- "The Eucharistic Christ - The Collection". Museo Nacional del Prado. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

Further reading

- Nicholl, Charles (17 April 2019). "The Last Leonardo by Ben Lewis review – secrets of the world's most expensive painting | Art and design books". The Guardian.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shaer, Matthew (14 April 2019). "The Invention of the 'Salvator Mundi'". Vulture. New York Magazine.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Alberti, Leon Battista. De Pictura. (Trans. Grayson). Phaidon. London. 1964. p. 63-4

- Allsop, Laura (7 November 2011). "Decoding da Vinci: How a lost Leonardo was found". CNN.

- Ames-Lewis, F. The Intellectual Life of The Early Renaissance Artist. Abbeville Press. p. 18, 275

- Nicola Barbatelli, Carlo Pedretti, Leonardo a Donnaregina. I Salvator Mundi per Napoli Elio De Rosa Editore; CB Edizioni, 9 January 2017. ISBN 8897644384 (Italian)

- Elworthy, F.T. The Evil Eye The Classic Account of An Ancient Superstition. Courier Dover Publications. 2004 p. 293.

- Hankins, J. 1999. The Study of the Timaeus in Early Renaissance Italy. Natural Particulars: Nature and the Disciplines in Renaissance Europe. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kemp, Martin. Leonardo da Vinci: the marvellous works of nature and man. Oxford University Press. 2006. pp. 208–9

- Kemp, Martin. Christ to Coke, How Image becomes Icon, Oxford University Press (OUP), 2011, ISBN 0199581118

- Vasari, G. Lives of the most eminent painters, sculptors, and architects. DeVere, G.C (Trans.) Ekserdijan, D.(ed.). Knopf. 1996. pp. 627–640; 710–748

- Zöllner, F. Leonardo da Vinci. The Complete Paintings and Drawings, Taschen, 2017

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salvator Mundi by Leonardo Da Vinci. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 16th-century paintings of Salvator mundi. |

- Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi makes auction history, Christies.com

- Robert Simon, Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi

- Robert Simon, Leonardo da Vinci Painting Discovered, Painting Gains Attribution After Careful Scholarship and Conservation, press release, 7 July 2011

- H. Niyazi, Authorship and the dangers of consensus 11 July 2011

- Frank Zöllner, Catalogue XXXII, Salvator Mundi, pp. 440–445 and Preface to the 2017 Edition pp. 15–17.

- Jean-Pierre Crettez, Internal geometry of "Salvator Mundi" (so-called Cook version, attributed to Leonardo da Vinci), 16 May 2019