List of genocides by death toll

This list of genocides by death toll includes estimates of all deaths which were directly or indirectly caused by genocide, as it is defined by the UN Convention. It excludes other mass killings, which are variously called mass murder, crimes against humanity, politicide, classicide, or war crimes, such as: the Thirty Years War (7.5 million deaths), Japanese war crimes (3 to 14 million deaths), the Red Terror (100,000 to 1.3 million deaths), the Atrocities in the Congo Free State (1 to 15 million deaths), the Great Purge (0.6 to 1.75 million deaths) or the Great Leap Forward and the famine which followed it (15 to 55 million deaths).

Definition

The United Nations Genocide Convention defines genocide as "acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group".[1]

List of genocides

Listed in descending order of lowest estimate.

| Event | Location | From | To | Lowest estimate |

Highest estimate |

Proportion of group killed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Holocaust[N 1] | 1941 | 1945 | 5,750,000 [3] |

6,000,000 [4] |

Around 2/3 of the Jewish population of Europe.[5] | ||

| Generalplan Ost[N 1] | 4,500,000 [6] |

13,700,000 [7] |

13.7% of the Soviet Union's population died during WWII The Third Reich planned to artificially decrease Baltic and Slavic populations by tens of millions, mostly by starvation, during and after the war.

Deaths include 1.3 million Jews, which are included in the deaths of 6 million Jews during the Holocaust,[4] as well as the deaths of more than 3 million Soviet POWs.[4] | ||||

| Holodomor (Голодомор)[N 2] (Ukrainian genocide which is part of greater Soviet famine of 1932–33) |

1932 | 1933 | 1,800,000 [19][20][21][22] |

7,500,000 [23][24][25][26][27] |

Genocide of Ukrainians through artificial starvation by the Soviet regime.[28][29] At least 10% of Ukraine's population perished.[30] Its characterization as a genocide is disputed by some historians.[31][32][33] | ||

| Nazi genocide of Poles[N 1] | 1939 | 1945 | 1,800,000 [4] |

3,000,000 [34] |

17% of Poland's population was killed or died during World War II | ||

| Mongol conquest of Western Xia[N 3] | Western Xia | 1205 | 1227 | 1,500,000 | 1,500,000 | 1,500,000 killed in the genocide after the conquest (Half[40] the population of Western Xia (3 million)[41][42][43] was exterminated) | |

| Cambodian genocide[N 4] | 1975 | 1979 | 1,386,734 [52][53] |

3,000,000 [47][54] |

10–33% of total population of Cambodia killed[55][56] including:

100% of Cambodian Viets | ||

| Kazakh genocide during the Soviet famine of 1932–33[N 5] |

1931 | 1933 | 1,300,000 [57] |

1,750,000 [58] |

Some historians conclude that 42% of the entire Kazakh population died in the famine.[58] The two Soviet census show that the number of the Kazakhs in Kazakhstan dropped from 3,637,612 in 1926 to 2,181,520 in 1937.[59] | ||

| Genocide in Bangladesh[N 6] by Pakistan |

1971 | 1,000,000 | 3,000,000 [61][62] |

2%[63] to 4%[64][65][66] Over 20% of Bengali Hindus killed[67] (Using 1 to 3 million deaths figures) | |||

| Armenian genocide Մեծ Եղեռն (Medz Yeghern, "Great Crime")[N 7] | (territories of present-day Turkey, Syria and Iraq) |

1915 | 1922 | 700,000 [68] |

1,800,000 [69] |

At least 50% of Armenians in Turkey killed[68] | |

| Indonesian genocide[N 8] | 1965 | 1966 | 500,000 [80][76][77] |

3,000,000 [78][79] |

Some scholars now argue that the Indonesian massacres constitute genocide by the legal definition.[81][71][75][82][83] | ||

| Rwandan genocide[N 9] | 1994 | 500,000 [84] |

1,071,000 [84] |

70% of Tutsis in Rwanda killed 1/3 of Twa in Rwanda killed 20% of Rwanda's total population killed | |||

| Greek genocide including the Pontic genocide[N 10] | (territories of present-day Turkey) |

1914 | 1922 | 500,000 [85] |

900,000 [86] |

At least 25% of Greeks in Anatolia (Turkey) killed | |

| Zunghar genocide 准噶尔灭族 in the Zunghar Khanate[N 11] | Qing Dynasty (Dzungaria) | 1755 | 1758 | 480,000 [90] |

600,000 [90] |

80% of 600,000 Zungharian Oirats killed | |

| Circassian genocide[N 12] | 1864 | 1867 | 400,000 [103] |

1,500,000 .[104] |

90% to 97% of total Circassian population perished or deported by the Russian forces.[105][106][107] | ||

| Genocide by the Ustaše including the Serbian genocide[N 13] | 1941 | 1945 | 320,000 [109][110] |

600,000 [109][110][111] |

13% to 21% of the Serbian population within the NDH was killed.[63] | ||

| Pacification of Algeria[N 14] |

1830 |

1871 |

300,000 |

1,000,000 |

10%[122] to 1/3[123][121] of Algeria's population died during the period | ||

| Genocide of indigenous peoples in Brazil[N 15] |

1900 |

1985 |

235,000 [130] |

800,000 [131] |

87 out of 230 Brazilian tribes went extinct during the period[132] | ||

| Albigensian Crusade (Cathar genocide)[N 16] |

1209 | 1229 | 200,000 [135] |

1,000,000 [136] |

|||

| Assyrian genocide ܣܝܦܐ (Seyfo, "Sword")[N 17] | 1915 | 1923 | 200,000 [137] |

750,000 [138] |

|||

| Irish genocide[N 18] | 1649 | 1653 | 200,000 [142] |

618,000 [143] |

20–40% of the population of Ireland perished during the Cromwellian conquest[142][143] | ||

| Wu Hu genocide[N 19] | Northern China | 350 | 351 | 200,000 [145] |

200,000 | ||

| Massacres of Hutus during the First Congo War[N 20] | 1996 | 1997 | 200, 000 [148] |

232, 000 [149] |

|||

| Armenian massacres of 1894-1896[N 21] | 1894 | 1896 | 200, 000 [156] |

300, 000 [156] |

|||

| Genocide of the Tencteri and Usipetes[N 22] | Germania | 55 BC | 150,000 [161] |

430,000 [162] |

|||

| Battle of Carthage (Punic genocide)[N 23] |

Carthage (territories of present-day Tunis, Tunisia) | 146 BC | 150,000 [168][163] |

150,000 | Population reduced from 500,000 to 55,000. 150,000 died in the fall of Carthage.[168] | ||

| Romani genocide[N 24] | 1935[173] | 1945 | 130,000 [174] |

500,000 [175][176] |

25% of Romani people in Europe killed | ||

| Polish Operation of the NKVD (Polish genocide)[N 25] | 1937 | 1938 | 111,091 [186] |

250,000 [187] |

22% of the Polish population of the USSR was "sentenced" by the operation (140,000 people)[188] | ||

| Aardakh[N 26] (Soviet deportation of Chechens and other Vainakh populations) |

1944 | 1948 | 100,000 [195] |

400,000 [196] |

23.5% to almost 50% of total Chechen population killed[197] | ||

| Genocide of Acholi and Lango people under Idi Amin[N 27] | 1972 | 1978 | 100, 000 [199] |

300, 000 [199] |

|||

| Darfur genocide[N 28] |

2003 |

Present |

98,000 [202] |

500,000 [203] |

|||

| Kurdish genocide[N 29] | 1977 | 1991 | 87,500 | 388,100 | 8% of the Kurdish population of Iraq was killed.[63] | ||

| East Timor genocide[N 30] | 1975 | 1999 | 85,320 [223] |

196,720 [224] |

13% to 44% of East Timor's total population killed (See death toll of East Timor genocide) | ||

| Ikiza[N 31] | 1972 | 80,000 [225][226] |

300,000 [227] |

5% of Burundi's population was killed in the 1972 genocide.[63] As much as 10% to 15% of the Hutu population of Burundi killed[227] | |||

| Libyan genocide[N 32] | 1923 | 1932 | 80,000 [232] |

125,000 [239] |

25% of Cyrenaican population killed[232] | ||

| Bambuti genocide[N 33] | 2002 | 2003 | 60,000 [242][240] |

70,000 [242] |

40% of the Eastern Congo's Pygmy population killed[N 34] | ||

| Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia[N 35] | 1943 | 1945 | 50,000 [245] |

300,000 [246][247][248][249][250] |

4% to 20% of the pre-war (1931) Second Polish Republic's total Polish population of Voivodeships: stanisławowskie, tarnopolskie and wołyńskie[251][252] where killed. | ||

| Genocide of Isaaqs[N 36] | 1988 | 1991 | 50,000 [268][258] |

200,000 [269] |

|||

| Genocidal crimes against Bosniaks and Croats by the Chetniks[N 37] | 1941 | 1945 | 50,000 [273] |

73,000 [273] |

|||

| Tamil Genocide[N 38] | 1956 | 2009 | 40,000[277][278] | 140,000+[279] | Between 10% and 35% of the Eelam Tamil population living in the de facto state of Tamil Eelam, controlled by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam.[280] | ||

| Deportation of the Crimean Tatars[N 39] | 1944 | 1948 | 34,000 [285] |

195,471 [286] |

The deportation and following exile reduced the Crimean Tatar population by between 18%[285] and 46%.[287] | ||

| Genocide in German South West Africa[N 40] | 1904 | 1908 | 34,000 [288] |

110,000 [289][290] |

60% (24,000 out of 40,000[288]) to 81.25% (65,000[291][292] out of 80,000[293]) of total Herero and 50%[288] of Nama population killed. | ||

| Guatemalan genocide[N 41] | 1962 | 1996 | 32,632 [298] |

166,000 [299] |

40% of the Maya population (24,000 people) of Guatemala's Ixil and Rabinal regions where killed[63] | ||

| Jewish genocide during the Russian White Terror[N 42] | what is now Ukraine and Russia | 1918 | 1923 | 30,000 [301][302] |

250,000 [300] |

||

| 1993 Genocide of Burundian Tutsis[N 31] | 1993 | 25,000 [304] |

50,000 [305] |

||||

| Genocide of Jews in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth by Cossack insurgents[N 43] | 1648 | 1657 | 18,000 [307] |

100,000 [308][309][310][311][312] |

45–50% of the Jewish population of Ukraine was killed.[307] | ||

| Latvian Operation of the NKVD (Latvian genocide)[N 44] |

1937 | 1938 | 16,573 [313] |

16,573 [314] |

|||

| 1984 anti-Sikh riots & Operation Woodrose[N 45] | 1984 | 1990 | 15,350 [N 46] |

29,000 [N 46] |

|||

| Parsley massacre[N 47] | 1937 | 12, 168 [334] |

35, 000 [334] |

||||

| California genocide[N 48] |

1846 |

1873 |

Amerindian population in California declined by 80% during the period | ||||

| Queensland Aboriginal genocide[N 49] |

1840 |

1897 |

10,000 [345] |

65,180 [346] |

3.3% to over 50% of the aboriginal population was killed (10,000[345] to 65,180[346] killed out of 125,600) | ||

| Rohingya genocide[N 50] |

2017 |

Present |

9,000–13,700 |

43,000 |

|||

| Decossackization[N 51] |

1917 |

1933 |

thousands–10,000+ |

1,000,000 |

|||

| Bosnian genocide[N 52] | 1992 | 1995 | 8,373 [368] |

31,107–39,199 [369][370] |

More than 3% of the Bosniak population of Bosnia and Herzegovina perished during the Bosnian War.[371] | ||

| Persecution of the Igbo by the Nigerian army[N 53] | 1966 | 1966 | 8,000[373] | 30,000[374] | |||

| The Sook Ching[N 54] | 1942 | 1942 | 5,000 |

25, 000 |

|||

| Chittagong Hill Tracts genocide[N 55] | 1977 | 1997 | 4,406 [384] |

13,206 [384] |

|||

| 1804 Haiti massacre[N 56] | 1804 | 1804 | 3,000[387] | 5,000[387] | |||

| Selk'nam genocide[N 57] | Late 19th century | Early 20th century | 2,500 [388] |

3,900 [389] |

84% The genocide reduced their numbers from around 3,000 to about 500 people. (Now pure Selk'nam are considered extinct.)[389][390] | ||

| Genocide of Yazidis by ISIL[N 58] | 2014 | 2019 | 2,100–4,400 [393] |

10,000 [394] |

See also: 2007 Yazidi communities bombings | ||

| Genocide of Shia muslims by ISIL, including Alawites and Druze | 2003 (as Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad and successor organizations including ISIL) | Present (as sleeper cells) | Several tens of thousands | 100,000+ | |||

| The Gukurahundi[N 59] | 1983 | 1987 | 2,000 [396] |

30, 000 [397] |

|||

| 1572 massacres of French Huguenots[N 60] | 1572 | 1572 | 2, 000 |

70, 000 [400] |

|||

| Genocide of the Moriori[N 61] | 1835 | 1863 | 1,900 [402][403] |

1,900 | 95% of the Moriori population was eradicated by the invasion from Taranaki, a group of Ngāti Mutunga and Ngāti Tama people from the Māori tribe.[404][405] All were enslaved and many were cannibalized.[406] They were not permitted to mix with their race.[407] The Moriori language is now extinct.[401][408] There are no Moriori of unmixed ancestry left.[403] | ||

| Conquest of the Desert and Mapuche decline[N 62] |

1870s |

1884 |

1,313 [409] |

225,000 [410] |

Mapuche population reduced from 250,000 to 25,000.[410] | ||

| Genocide of Christians by ISIL | 2003 (as Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad and successor organizations including ISIL | Ongoing (elsewhere in the world, as ISIL has lost all territory) | 1000+ | Thousands | More than 2,000 native Christians killed in the territories controlled by ISIL or with sleeper cells, including the 2010 Baghdad church massacre, 2015 kidnapping and beheading of Copts in Libya, the 2017 Palm Sunday church bombings, the 2019 Jolo Cathedral bombings and the 2019 Sri Lanka Easter bombings, among others. See also: Boko Haram insurgency | ||

| Destruction of the Aché[N 63] | 1956 | Early 1970s | 900 [412] |

4,000 [413] |

85% of the Aché were wiped out (Today Aché are considered extinct). | ||

| Black War (Genocide of Aboriginal Tasmanians)[N 64] |

Mid 1820s | 1832 | 400 [416] |

1,000 [416] |

|||

Gallery

Expulsion of Circassian during the Circassian genocide

Expulsion of Circassian during the Circassian genocide Emaciated corpses of children in Warsaw Ghetto during the Holocaust

Emaciated corpses of children in Warsaw Ghetto during the Holocaust Starved victims of the Holodomor

Starved victims of the Holodomor- Skulls of Khmer Rouge victims of the Cambodian genocide

Victims of Armenian genocide

Victims of Armenian genocide Rwandan genocide skulls

Rwandan genocide skulls Greek genocide victims

Greek genocide victims

Excavation of the corpses of victims of the Guatemalan genocide

Excavation of the corpses of victims of the Guatemalan genocide Bosnian genocide corpses

Bosnian genocide corpses Julius Popper carrying out Selk'nam genocide

Julius Popper carrying out Selk'nam genocide Anfal genocide graves

Anfal genocide graves East Timor genocide graves

East Timor genocide graves Portrays Dzungar genocide

Portrays Dzungar genocide- Portrays Cathar genocide

Mother with sick baby during Darfur genocide

Mother with sick baby during Darfur genocide Exhumed remains of the Isaaq genocide in 2014

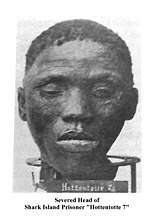

Exhumed remains of the Isaaq genocide in 2014 Heads used for medical experimentation during the Herero and Namaqua genocide

Heads used for medical experimentation during the Herero and Namaqua genocide Concentration camp during the Libyan Genocide

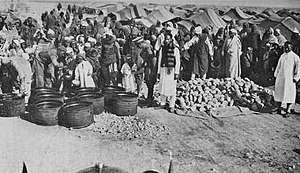

Concentration camp during the Libyan Genocide.jpg) Rohingya refugees in a refugee camp after fleeing the Rohingya genocide in Myanmar

Rohingya refugees in a refugee camp after fleeing the Rohingya genocide in Myanmar

See also

- Casualty recording

- Genocidal massacre

- Genocide of indigenous peoples

- Genocides in history

- Hamoodur Rahman Commission

- List of ongoing military conflicts

- List of anthropogenic disasters and atrocities by death toll

- List of wars by death toll

Political extermination campaigns

- Anti-communist mass killings

- Dirty War

- Mass killings of landlords under Mao Zedong (1949–1951)

- Mass killings under Communist regimes

- Operation Condor

- Qey Shibir

- White Terror (Spain)

Notes

- 'Initially it was carried out in German-occupied Eastern Europe by paramilitary death squads (Einsatzgruppen) by shooting or, less frequently, using ad hoc built gassing vans, and later in extermination camps by gassing.[2]

By extending its definition the Holocaust may also refer to the other victims of German war crimes during the rule of Nazism, such as the Romani genocide's victims, Poles and other Slavic civilian populations and POWs, victims of Germany's eugenics program, political opponents, homosexuals, Jehovah's Witnesses, and civil hostages and resisters from all over Europe during World War II. - In 2003 Holodomor, the man-made famine in Ukraine, was recognized by the United Nations as the result of actions and policies of the Soviet government of Joseph Stalin that caused millions of deaths,[8] and in 2008 by the European Parliament as a crime against the Ukrainian people, and against humanity.[9] Holodomor is considered a genocide in Ukraine,[10], Australia,[11] Canada,[12] Colombia,[13] Ecuador,[14] Estonia,[15] Georgia,[15] Hungary,[15] Latvia,[15] Lithuania,[15] Mexico,[15] Paraguay,[15] Peru,[15] Poland,[16] and Vatican City,[15] while the Russian Federation views it as part of the wider Soviet famine of 1932–33.[17] Scholars are divided and their debate is inconclusive on whether the Holodomor falls under the definition of genocide.[18]

- The Mongol conquest of Western Xia was a series of conflicts between the Mongol Empire and the Western Xia (Xi Xia) dynasty, also known as the Tangut Empire. Hoping to gain both plunder and a powerful vassal state, Mongol leader Genghis Khan commanded some initial raids against Western Xia before launching a full-scale invasion in 1209. This marked both the first major invasion conducted by Genghis and the beginning of the Mongol invasion of China. Despite a major set-back during a nearly year-long siege of the capital, Yinchuan, when the diverted river accidentally flooded their camp, the Mongols convinced Emperor Li Anquan to surrender in January 1210. For nearly a decade the Western Xia served the Mongols as vassals and aided them in the Mongol–Jin War, but when Genghis invaded the Islamic Khwarazmian dynasty in 1219, Western Xia attempted to break away from the Empire and ally with the Jin and Song dynasties. Angered by this betrayal, in 1225 Genghis Khan sent a second, punitive expedition into Western Xia. Genghis intended to annihilate the entire Western Xia culture, and his campaign systematically destroyed Western Xia cities and the countryside, culminating in the siege of the capital in 1227 along with forays into Jin territory. Near the end of the siege, in August 1227, Genghis Khan died from an uncertain cause, though some accounts say he was killed in action against Western Xia. After his death, Yinchuan fell to the Mongols and most of its population was massacred. The destruction of Western Xia during the second campaign was near total. According to John Man, Western Xia is little known to anyone other than experts in the field precisely because of Genghis Khan's policy calling for their complete eradication. He states that "There is a case to be made that this was the first ever recorded example of attempted genocide. It was certainly very successful ethnocide."[35] However, some members of the Western Xia royal clan emigrated to western Sichuan, northern Tibet, even possibly Northeast India, in some instances becoming local rulers.[36] A small Western Xia state was established in Tibet along the upper reaches of the Yalong River while other Western Xia populations settled in what are now the modern provinces of Henan and Hebei.[37] In China, remnants of the Western Xia persisted into the middle of the Ming dynasty.[38][39]

- The Cambodian genocide was carried out by the Khmer Rouge led by Pol Pot[44] who, planning to create a form of agrarian socialism founded on an extremist ideology coupled with ethnic hostility, forced the urban population to relocate savagely to the countryside, among torture, mass executions, forced labor, and starvation.

[45][46][47] The genocide ended in 1979 with the Cambodian invasion by the Vietnamese army.[48] Up to 20,000 mass graves, the infamous Killing Fields, were uncovered,[49] where at least 1,386,734 murdered victims found their final resting place.[50] On 7 August 2014, two top leaders, Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan, received life sentences for crimes against humanity.[51] - Genocide of Kazakhs through artificial starvation by the USSR.

- Genocide in Bangladesh. Massacres, killings, rape, arson and systematic elimination of religious minorities (particularly Hindus), political dissidents and the members of the liberation forces of Bangladesh were conducted by the Pakistan Army with support from paramilitary militias—the Razakars, Al-Badr and Al-Shams—formed by the radical Islamist Jamaat-e-Islami party.[60]

- The extermination of the Armenians, carried out by the Young Turks, led to the coining of the word "genocide". It included massacres, forced deportations involving death marches, mass starvation, and occurred concurrently with the Assyrian and Greek genocides. The State of Turkey denies a genocide ever occurred.

- [70][71][72]:4 Indonesian Communist Purge, Indonesian politicide,[73][74] (or the 1965 Tragedy) were large-scale killings and civil unrest that occurred in Indonesia over several months, targeting communist sympathizers, ethnic Chinese and alleged leftists, often at the instigation of the armed forces and government. It began as an anti-communist purge following a controversial attempted coup d'état by the 30 September Movement in Indonesia. The most widely published estimates were that 500,000 to more than one million people were killed,[72][75][76][77] with some more recent estimates going as high as two to three million.[78][79] The purge was a pivotal event in the transition to the "New Order" and the elimination of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) as a political force, with impacts on the global Cold War. The upheavals led to the fall of President Sukarno and the commencement of Suharto's three-decade authoritarian presidency.

- Some 50 perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide have been found guilty by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, but most others have not been charged due to lack of witness accounts. Another 120,000 were arrested by Rwanda; of these, 60,000 were tried and convicted in the Gacaca court system. Perpetrators who fled into Zaire (Democratic Republic of the Congo) were used as a justification when Rwanda and Uganda invaded Zaire (First and Second Congo Wars). It is recognized by the international community as a genocide.

- For the Greek genocide other sources give 500,000-1,200,000 casualties between Pontic, Cappadocian and Ionians Greeks. The genocide, instigated by the Ottoman government, included massacres, forced deportations involving death marches, summary expulsions, arbitrary executions, and destruction of Greek Orthodox cultural, historical and religious monuments.

- Zunghar genocide. The Manchu Qianlong Emperor of Qing China issued his orders for his Manchu Bannermen to carry out the genocide and eradication of the Zunghar nation, ordering the massacre of all the Zunghar men and enslaving Zunghar women and children.[87] The Qianlong Emperor moved the remaining Zunghar people to the mainland and ordered the generals to kill all the men in Barkol or Suzhou, and divided their wives and children to Qing soldiers.[88][89] The Qing soldiers who massacred the Zunghars were Manchu Bannermen and Khalkha Mongols. In an account of the war, Wei Yuan wrote that about 40% of the Zunghar households were killed by smallpox, 20% fled to Russia or the Kazakh Khanate, and 30% were killed by the army, leaving no yurts in an area of several thousands of Chinese miles except those of the surrendered.[90][91][92] Clarke wrote 80%, or between 480,000 and 600,000 people, were killed between 1755 and 1758 in what "amounted to the complete destruction of not only the Zunghar state but of the Zunghars as a people."[90][93] Historian Peter Perdue has shown that the decimation of the Dzungars was the result of an explicit policy of extermination launched by the Qianlong Emperor.[90] Although this "deliberate use of massacre" has been largely ignored by modern scholars,[90] Mark Levene, a historian whose recent research interests focus on genocide, has stated that the extermination of the Dzungars was "arguably the eighteenth century genocide par excellence".[94]

- The Circassian genocide refers to the ethnic cleansing, massive annihilation, displacement,[95] destruction and expulsion of the majority of the indigenous Circassians from historical Circassia, which roughly encompassed the major part of the North Caucasus and the northeast shore of the Black Sea. This occurred in the aftermath of the Caucasian War in the last quarter of the 19th century.[96] The displaced people moved primarily to the Ottoman Empire. Former Russian President Boris Yeltsin's May 1994 statement admitted that resistance to the tsarist forces was legitimate, but he did not recognize "the guilt of the tsarist government for the genocide."[97] In 1997 and 1998, the leaders of Kabardino-Balkaria and of Adygea sent appeals to the Duma to reconsider the situation and to issue the needed apology; to date, there has been no response from Moscow. In October 2006, the Adygeyan public organizations of Russia, Turkey, Israel, Jordan, Syria, the United States, Belgium, Canada and Germany have sent the president of the European Parliament a letter with the request to recognize the genocide against Adygean (Circassian) people.[98] On May 21, 2011, the Parliament of Georgia passed a resolution, stating that "pre-planned" mass killings of Circassians by Imperial Russia, accompanied by "deliberate famine and epidemics", should be recognized as "genocide" and those deported during those events from their homeland, should be recognized as "refugees". Georgia, which has poor relations with Russia, has made outreach efforts to North Caucasian ethnic groups since the 2008 Russo-Georgian War.[99] Following a consultation with academics, human rights activists and Circassian diaspora groups and parliamentary discussions in Tbilisi in 2010 and 2011, Georgia became the first country to use the word "genocide" to refer to the events.[99][100][101] On 20 May 2011 the parliament of the Republic of Georgia declared in its resolution[102] that the mass annihilation of the Cherkess (Adyghe) people during the Russian-Caucasian war and thereafter constituted genocide as defined in the Hague Convention of 1907 and the UN Convention of 1948.

- Genocide by the Ustaše including the Serbian Genocide. The government of the Independent State of Croatia murdered Serbs, Jews, Romani, and some dissident Croats and Bosniaks inside its borders, many in concentration camps, most notably Jasenovac camp. Ante Pavelić, the leader of the Ustaše, enacted racial laws similar to those of Nazi Germany, declaring Jews, Romani, and Serbs "enemies of the people of Croatia". He escaped to Spain after the war with the assistance of the Roman Catholic Church and fatally injured there some years later in an assassination attempt.[108]

- Over the course of the French conquest of Algeria (especially the Pacification of Algeria) there where a series of demographic catastrophes in Algeria due to a variety of factors. The demographic crisis was such that, in a more than 300 page demographic study, Dr. René Ricoux, head of demographic and medical statistics at the statistical office of the General Government of Algeria, foresaw the simple disappearance of Algerian "natives as a whole."[112] Algerian demographic change can be divided into three phases: an almost constant decline during the conquest period, up until its most heavy drop from an estimated 2.7 million in 1861 to a brutal fall to 2.1 million in 1871, and finally moving into a gradual arising[113] to a level of three million inhabitants by 1890. Causes range from a series of famines, diseases, emigration;[114] to the violent methods used by the French army during their Pacification of Algeria which Turkey[115][116] and some historians[117] argue to constitute acts of genocide; however, other sources contest this.[118][119]

- The process that has been described as the genocide of indigenous peoples in Brazil began with the Portuguese colonization of the Americas, when Pedro Álvares Cabral made landfall in what is now the country of Brazil in 1500. This started the process that led to the depopulation of the indigenous peoples in Brazil, because of disease and violent treatment by European settlers, and their gradual replacement with colonists from Europe and Africa. Over eighty indigenous tribes were destroyed between 1900 and 1957, and the overall indigenous population declined by over eighty percent, from over one million to around two hundred thousand. The 1988 Brazilian Constitution recognises indigenous peoples' right to pursue their traditional ways of life and to the permanent and exclusive possession of their "traditional lands", which are demarcated as Indigenous Territories.[124] In practice, however, Brazil's indigenous people still face a number of external threats and challenges to their continued existence and cultural heritage.[125] The process of demarcation is slow—often involving protracted legal battles—and FUNAI do not have sufficient resources to enforce the legal protection on indigenous land.[126][125][127][128][129]

- The Albigensian Crusade was a 20-year military campaign initiated by Pope Innocent III to eliminate Catharism, a Christian sect, in Languedoc, in southern France. The Catholic Church considered them heretics and ordered that they should be completely eradicated. Raphael Lemkin referred to the Albigensian Crusade as "one of the most conclusive cases of genocide in religious history".[133] Kurt Jonassohn and Karin Solveig Björnson describe it as "the first ideological genocide."[134]

- The Assyrian genocide is commonly known as "Seyfo" (which means sword in Assyrian). It occurred concurrently with the Armenian and Greek genocides.

- The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland or Cromwellian war in Ireland (1649–53) refers to the conquest of Ireland by the forces of the English Parliament, led by Oliver Cromwell, during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Cromwell invaded Ireland with his New Model Army on behalf of England's Rump Parliament in August 1649. Following the Irish Rebellion of 1641, most of Ireland came under the control of the Irish Catholic Confederation. In early 1649, the Confederates allied with the English Royalists, who had been defeated by the Parliamentarians in the English Civil War. By May 1652, Cromwell's Parliamentarian army had defeated the Confederate and Royalist coalition in Ireland and occupied the country—bringing to an end the Irish Confederate Wars (or Eleven Years' War). However, guerrilla warfare continued for a further year. Cromwell passed a series of Penal Laws against Roman Catholics (the vast majority of the population) and confiscated large amounts of their land. During the Interregnum (1651–1660), this policy was enhanced with the passing of the Act of Settlement of Ireland in 1652. Its goal was a further transfer of land from Irish to English hands. The immediate war aims and the longer term policies of the English Parliamentarians resulted in an attempt by the English to transfer the native population to the western fringes to make way for Protestant settlers. This policy was reflected in a phrase attributed to Cromwell: "To Hell or to Connaught" and has been described by historians as genocide.[139] The Biblical account of Joshua and the Battle of Jericho was used by Oliver Cromwell to justify genocide against Catholics.[140]:3[141]

- When he heard of the Jie revolt against him, Ran Min issued his famous "extermination order", in which he called on the Chinese to kill all the Wu Hu. The Wu Hu had conquered Ran Wei half a century earlier. The effect of Ran Min's order was immense; some 200,000 Jie were killed in Yecheng (the Wei capital) in a few days, and brutal fighting broke out between Chinese and Wu Hu throughout North China.[144]

- During the First Congo War, troops of the Rwanda-backed Alliance des Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Congo-Zaïre (AFDL) attacked refugee camps in Eastern DRC, home to 527,000 and 718,000 Hutu refugees in South-Kivu and North-Kivu respectively.[146] Elements of the AFDL and, more so, of the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA) systematically shelled numerous camps and committed massacres with light weapons. These early attacks cost the lives of 6,800-8,000 refugees and forced the repatriation of 500,000 - 700,000 refugees back to Rwanda.[147] As survivors fled westward of the DRC, the AFDL units hunted them down and attacked their makeshift camps, killing thousands more.[148] These attacks and killings continued to intensify as refugees moved westward as far as 1,800 km away. The report of the United Nations Joint Commission reported 134 sites where such atrocities were committed. On 8 July 1997, the acting UN High Commissioner for Human Rights stated that "about 200,000 Hutu refugees could well have been massacred".[148]

- The Hamidian massacres (Armenian: Համիդյան ջարդեր, Turkish: Hamidiye Katliamı, French: Massacres hamidiens), also referred to as the Armenian Massacres of 1894–1896[150] and Armenian genocide,[150] were massacres of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire that took place in the mid-1890s. It was estimated casualties ranged from 80,000 to 300,000,[151] resulting in 50,000 orphaned children.[152] The massacres are named after Sultan Abdul Hamid II, who, in his efforts to maintain the imperial domain of the collapsing Ottoman Empire, reasserted Pan-Islamism as a state ideology.[153] Although the massacres were aimed mainly at the Armenians, they turned into indiscriminate anti-Christian pogroms in some cases, such as the Diyarbekir massacre, where, at least according to one contemporary source, up to 25,000 Assyrians were also killed.[154] The massacres began in the Ottoman interior in 1894, before becoming more widespread in the following years. Between 1894 and 1896 was when the majority of the murders took place. The massacres began tapering off in 1897, following international condemnation of Abdul Hamid. The harshest measures were directed against the long persecuted Armenian community as calls for civil reform and better treatment from the government went ignored. The Ottomans made no allowances for the victims' age or gender, and massacred all with brutal force.[155] This occurred at a time when the telegraph could spread news around the world, and the massacres received extensive coverage in the media of Western Europe and North America.

- In his Commentarii de Bello Gallico, Caesar describes how two tribes, the Tencteri and Usipetes, had been driven from their traditional lands by the Germanic Suebi, whose military dominance had led to constant warfare and neglect of agriculture. This original homeland of the two tribes is not clear but by the time of Caesar the Suebi had settled in a very large wooded area to the east of the Ubii, who at this time lived on the east bank of the Rhine, on the opposite bank from where Cologne is today. It has been argued that the Tencteri and Usipetes specifically may have come from the area of the Weser river to the east of the Sigambri, because it is near to where the two tribes appeared on the Rhine, and Caesar reports the Suevi in this area. It would also explain the apparently friendly relations of the Tencteri and Usipetes with the Sigambri, who might have been their traditional neighbours.[157] (In later Roman times this area inhabited by Caesar's Suebi was inhabited by the Chatti.[158]) Caesar, fearing how the Gauls on the left bank might react, hurried to deal with this threat to his command of the region. He discovered that a number of Gaulish tribes had attempted to pay these Germani generously to leave, but the Tencteri and Usipetes had ranged further, coming to the frontiers of the Condrusi and Eburones, who were both under the protection of the Treveri to their south. Caesar convened a meeting of the Gaulish chiefs, and, pretending he did not know of their attempts at bribery, demanded cavalry and provisions for war against the Tencteri and Usipetes. The Germanic cavalry, although outnumbered by Caesar's Gallic horsemen, made the first attack, forcing the Romans to retreat. Caesar describes a characteristic battle-tactic they used, where a horsemen would leap down to their feet and stab enemy horses in the belly. Accusing them of violating the truce, Caesar refused to accept any more ambassadors, arresting some who came requesting a further truce, and led his full force against the Germanic camp. The Usipetes and Tencteri were thrown into disarray and forced to flee, pursued by Caesar's cavalry, to the confluence of the Rhine and Meuse. Many were killed attempting to cross the rivers.[159][160] They found refuge on the other side of the Rhine amongst the Sicambri. Caesar's campaign against the Tencteri and Usipetes have been characterized a genocidal.[161][162]

- The massacre of Carthaginians (Punics) during their defeat by the Roman Republic is considered a genocide by many scholars.[163][164][165][166][167]

- Porajmos (Romani pronunciation: IPA: [pʰoɽajˈmos]), or Samudaripen ("Mass killing"), the Romani genocide or Romani Holocaust, was the planned and attempted effort by the government of Nazi Germany and its allies to exterminate part of the Romani people of Europe. On 26 November 1935, a supplementary decree to the Nuremberg Laws stripping Jews of their German citizenship expanded the category "enemies of the race-based state" to include Romani, the same category as the Jews, and in some ways they had similar fates.[169][170] In 1982, West Germany formally recognized that genocide had been committed against the Romani.[171] In 2011, the Polish Government passed a resolution for the official recognition of 2 August as a day of commemoration of the genocide.[172]

- The Polish Operation of the NKVD was a mass murder specifically aimed at the Polish ethnic group in the USSR by the orders of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. Historian Michael Ellman asserts that the 'national operations', particularly the 'Polish operation', may constitute genocide as defined by the UN convention.[177] His opinion is shared by Simon Sebag Montefiore, who calls the Polish operation of the NKVD 'a mini-genocide.'[178] Polish writer and commentator, Dr Tomasz Sommer, also refers to the operation as a genocide, along with Prof. Marek Jan Chodakiewicz among others.[179][180][181][182][183][184][185]

- Aardakh also known as Operation Lentil (Russian: Чечевица, Chechevitsa; Chechen: Вайнах махкахбахар Vaynax Maxkaxbaxar) was the Soviet expulsion of the whole of the Vainakh (Chechen and Ingush) populations of the North Caucasus to Central Asia during World War II. The expulsion, preceded by the 1940–1944 insurgency in Chechnya, was ordered on 23 February 1944 by NKVD chief Lavrentiy Beria after approval by Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin, as a part of Soviet forced settlement program and population transfer that affected several million members of non-Russian Soviet ethnic minorities between the 1930s and the 1950s.

The deportation encompassed their entire nations, well over 500,000 people, as well as the complete liquidation of the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. Hundreds of thousands[189][190][191] [192] of Chechens and Ingushes died or were killed during the round-ups and transportation, and during their early years in exile. The survivors would not return to their native lands until 1957. Many in Chechnya and Ingushetia classify it as an act of genocide, as did the European Parliament in 2004.[193][194] - After Idi Amin Dada overthrow the regime of Milton Obote in 1971, he declared the Acholi and Lango tribes enemies, as Obote was a Lango and he saw the fact that they dominated the army as a threat.[199] In January 1972, Amin issued an order to the Ugandan army ordering that they assemble and kill all Acholi or Lango soldiers, and then commanded that all Acholi and Lango be rounded up and confined within army barracks, where they were either slaughtered by the soldiers or killed when the Ugandan air force bombed the barracks.[199]

- The Darfur genocide refer to the war crimes and crimes against humanity such as massacre and genocidal rape that occurred within the Darfur region during the War in Darfur perpetrated by Janjaweed militias and the Sudanese government. These atrocities have been called the first genocide of the 21at century.[200] Sudan's president Omar al-Bashir has been indicted for his role in the genocide by the United Nations.[201]

- Saddam Hussein's campaign against the Kurds including the Al-Anfal campaign and the Feyli Kurds operations have been recognized as genocides: On 5 December 2012, Sweden's parliament, the Riksdag, adopted a resolution by the Green party to officially recognize Anfal as genocide. The resolution was passed by all 349 members of parliament.[204] On 28 February 2013, the British House of Commons formally recognized the Anfal as genocide following a campaign led by Conservative MP Nadhim Zahawi, who is of Kurdish descent.[205] South Korea recognized the Anfal as genocide on June 13 of 2013.[206] In 2011, the Iraqi Parliament voted to recognize the 1980 massacre of Feyli Kurds under the regime of Saddam Hussein as genocide.[207] The destruction of Kurdish villages during the Iraqi Arabization campaign refers to villages razed by the Ba'athist Iraqi government during its "Arabization campaign" of areas, excluded from Kurdistan under the Iraqi–Kurdish Autonomy Agreement of 1970. 1.5 to 2 million Kurds were forcibly displaced by Arabization campaigns in Iraq between 1963 and 1987;[208] resulting in 10,000 to 100,000 deaths during the displacements;[208]87,500 to 388,100 Kurds were killed in the destruction of Kurdish villages during the Iraqi Arabization campaign including: 2,500[209] to 12,500[209] in the Ba'athist Arabization campaigns in North Iraq, 10,000[210] to 25,000[211][212] were killed during the Feyli Kurds operation, 5,000[213] to 8,000[214] Kurds disappeared in the 1983 Barzani killings, 50,000[215] to 100,000[215] (although Kurdish sources have cited a higher figure of 182,000[216]) more Kurds were massacred in the Anfal genocide, and at least 20,000[217] were killed during the 1991 Iraqi uprising notwithstanding an additional 48,400[218] to 140,600[218] Kurdish refugees that starved to death along the Iranian and Turkish borders.

- The East Timor genocide refers to the "pacification campaigns" of state sponsored terror by the Indonesian government during their occupation of East Timor. Oxford University held an academic consensus calling the Indonesian Occupation of East Timor genocide and Yale university teaches it as part of their "Genocide Studies" program.[219][220] Precise estimates of the death toll are difficult to determine. The 2005 report of the UN's Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor (CAVR) reports an estimated minimum number of conflict-related deaths of 102,800 (+/− 12,000). Of these, the report says that approximately 18,600 (+/− 1,000) were either killed or disappeared, and that approximately 84,000 (+/− 11,000) died from hunger or illness in excess of what would have been expected due to peacetime mortality. These figures represent a minimum conservative estimate that CAVR says is its scientifically-based principal finding. The report did not provide an upper bound, however, CAVR speculated that the total number of deaths due to conflict-related hunger and illness could have been as high as 183,000.[221] The truth commission held Indonesian forces responsible for about 70% of the violent killings.[222]

- Burundian genocide. In the long sequence of civil fights that occurred between Tutsi and Hutu since Burundi's independence in 1962, the 1972 mass killings of Hutu by the Tutsi and the 1993 mass killings of Tutsis by the majority-Hutu populace are both described as genocide in the final report of the International Commission of Inquiry for Burundi presented to the United Nations Security Council in 1996.

- The Pacification of Libya,[228] also known as the Libyan Genocide[229][230][231][232] or Second Italo-Senussi War,[233] was a prolonged conflict in Italian Libya between Italian military forces and indigenous rebels associated with the Senussi Order that lasted from 1923 until 1932,[234][235] when the principal Senussi leader, Omar Mukhtar, was captured and executed.[236] The pacification resulted in mass deaths of the indigenous people in Cyrenaica—one quarter of Cyrenaica's population of 225,000 people died during the conflict.[229] Italy committed major war crimes during the conflict; including the use of chemical weapons, episodes of refusing to take prisoners of war and instead executing surrendering combatants, and mass executions of civilians.[232] Italian authorities committed ethnic cleansing by forcibly expelling 100,000 Bedouin Cyrenaicans, half the population of Cyrenaica, from their settlements that were slated to be given to Italian settlers.[228][237] Italy apologized in 2008 for its killing, destruction and repression of the Libyan people during the period of colonial rule, and went on to say that this was a "complete and moral acknowledgement of the damage inflicted on Libya by Italy during the colonial era."[238]

- Effacer le tableau ("erasing the board") is the operational name given to the systematic extermination of the Bambuti pygmies by rebel forces in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The primary objective of Effacer le tableau was the territorial conquest of the North Kivu province of the DRC and ethnic cleansing of Pygmies from the Congo's eastern region whose population numbered 90,000 by 2004.[240] [241]

- Eastern Pygmy population was reduced to 90,000 after a campaign that killed 60,000[242] implying a 40% decline

- Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia was a genocide carried out in Nazi German-occupied Poland by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (the UPA) against Poles in the area of Volhynia, Eastern Galicia, parts of Polesia and Lublin region, beginning in 1943 and lasting up to 1945. On 22 July 2016, the Parliament of Poland passed a resolution recognizing the massacres as Genocide[243][244]

- The Genocide of Isaaqs or "Hargeisa Holocaust"[253][254] was the systematic, state-sponsored massacre of Isaaq civilians between 1988 and 1991 by the Somali Democratic Republic under the dictatorship of Siad Barre.[255] The number of civilian deaths in this massacre is estimated to be between 50,000–100,000 according to various sources,[256][257][258] while local reports estimate the total civilian deaths to be upwards of 200,000 Isaaq civilians.[259] This included the leveling and complete destruction of the second and third largest cities in Somalia, Hargeisa (90 per cent destroyed)[260] and Burao (70 per cent destroyed) respectively,[261] and had caused 400,000[262][263] Somalis (primarily of the Isaaq clan) to flee their land and cross the border to Hartasheikh in Ethiopia as refugees, creating the world's largest refugee camp then (1988),[264] with another 400,000 being internally displaced.[265][266][267] In 2001, the United Nations commissioned an investigation on past human rights violations in Somalia,[255] specifically to find out if "crimes of international jurisdiction (i.e. war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide) had been perpetrated during the country's civil war". The investigation was commissioned jointly by the United Nations Co-ordination Unit (UNCU) and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. The investigation concluded with a report confirming the crime of genocide to have taken place against the Isaaqs in Somalia.[255]

- Massacres of ethnic Croats and Muslims by Serbian Chetniks across large areas of the Independent State of Croatia (modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Sandžak) during World War II in Yugoslavia. Genocidal characteristics of the massacres can be seen through the Moljević plan ("On Our State and Its Borders") and the 1941 'Instructions' issued by Chetnik leader, Draža Mihailović, concerning the cleansing of non-Serbs on the basis of creating a post-war Greater Serbia.[270][271][272] Death toll by ethnicity includes between 50,000-68,000 (18,000 to 32,000 Croats and 29,000 to 33,000 Muslims) killed in areas of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia, and another 5,000 Muslims killed in Sandžak.[273][274][275][276]

- Massacres of ethnic Tamils across Sri Lanka, but especially in the North-East of the island, claimed as the Tamil homeland, have occurred repeatedly since 1956. Tens of thousands of Tamils were killed over the years. Tamils have made allegations of genocide since the 80s and in 2015 the Northern Provincial Council passed a resolution on the Tamil Genocide, seeking a UN inquiry. The Canadian Parliament in 2019 also called for an investigation into genocide allegations. Sri Lanka has strongly denied the accusations of genocide.

- The deportation of the Crimean Tatars (Crimean Tatar Qırımtatar halqınıñ sürgünligi; Ukrainian Депортація кримських татар; Russian Депортация крымских татар) was the ethnic cleansing of at least 191,044 Crimean Tatars or, according to the other sources, 423,100 of them (89,2 % were women, children and elderly people) in 18–20 May 1944; one of the crimes of the Soviet totalitarian regime. It was carried out by Lavrentiy Beria, head of the Soviet state security and secret police, acting on behalf of Joseph Stalin. Within three days, Beria's NKVD used cattle trains to deport women, children, the elderly, even Communists and members of the Red Army, to the Soviet Republic of Uzbekistan, several thousand kilometres away. They were one of the ten ethnicities who were encompassed by Stalin's policy of population transfer in the Soviet Union. The deportation is recognized as a genocide by the countries of Ukraine, Latvia, Lithuania, and Canada respectively; as well as various scholars. Professor Lyman H. Legters argued that the Soviet penal system, combined with its resettlement policies, should count as genocidal since the sentences were borne most heavily specifically on certain ethnic groups, and that a relocation of these ethnic groups, whose survivial depends on ties to its particular homeland, "had a genocidal effect remediable only by restoration of the group to its homeland".[281] Soviet dissidents Ilya Gabay[282] and Pyotr Grigorenko[283] both classified the event as a genocide. Historian Timothy Snyder included it in a list of Soviet policies that "meet the standard of genocide."[284]

- The Genocide in German South West Africa was the campaign to exterminate the Herero and Nama people that the German Empire undertook in German South-West Africa (modern-day Namibia). It is considered one of the first genocides of the 20th century.

- Guatemalan genocide. The government forces of Guatemala and allied paramilitary groups have been condemned by the Historical Clarification Commission for committing genocide against the Maya population[294][295] and for widespread human rights violations against civilians during the civil war fought against various leftist rebel groups. At least an estimated 200,000 persons lost their lives by arbitrary executions, forced disappearances and other human rights violations.[296] A quarter of the direct victims of human rights violations and acts of violence were women.[297]

- The Whitaker Report of the United Nations used the massacre of 100,000 to 250,000 Jews in more than 2,000 pogroms during the White Terror in Russia as an example of genocide.[300] During the Russian Civil War, between 1918 and 1921 a total of 1,236 violent incidents against Jews occurred in 524 towns in Ukraine. The estimates of the number of killed range between 30,000 and 60,000.[301][302] Of the recorded 1,236 pogroms and excesses, 493 were carried out by Ukrainian People's Republic soldiers under command of Symon Petliura, 307 by independent Ukrainian warlords, 213 by Denikin's army, 106 by the Red Army and 32 by the Polish Army.[303]

- During the Khmelnytsky Uprising genocidal massacres were perpetrated against Jewish communities in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth by Ukrainian Cossacks and Crimean Tatars.[306]

- The Latvian Operation refers to mass arrest and execution of Latvians during the Stalinist Great Purge.

- The Persecution of Sikhs by India has been characterized as genocidal. Many Indians of different religions made significant efforts to hide and help Sikh families during the rioting.[315] The Sikh Jathedar of Akal Takht declared the events following the death of Indira Gandhi a Sikh "genocide", replacing "anti-Sikh riots" widely used by the Indian government, the media and writers, on 15 July 2010.[316] The decision came soon after a similar motion was raised in the Canadian Parliament by a Sikh MP. Although several political parties and governments have promised compensation for the families of riot victims, compensation has not yet been paid.[317] On 16 April 2015, Assembly Concurrent Resolution 34 (ACR 34) was passed by the California State Assembly. Co-authored by Sacramento-area assembly members Jim Cooper, Kevin McCarty, Jim Gallagher and Ken Cooley, the resolution criticized the Government of participating in and failure to prevent the killings. The assembly called the killings a "genocide", as it "resulted in the intentional destruction of many Sikh families, communities, homes and businesses."[318][319] In April 2017, the Ontario Legislature passed a motion condemning the anti-Sikh riots as "genocide".[320] The Indian government lobbied against the motion and condemned it upon its adoption.[321] In February 2018, American state of Connecticut, passed a bill stating, 30 November of each year to be "Sikh Genocide" Remembrance Day to remember the lives lost on 30 November 1984, during the Sikh Genocide.[322] The Akal Takht, Sikhism's governing body, considers the killings genocide.[323] Operation Woodrose; a military operation carried out by the Indira Gandhi-led Indian government in the months after Operation Blue Star to "prevent the outbreak of widespread public protest" in the state of Punjab[324] has also been characterized as a genocide.[325] The government arrested all prominent members of the largest Sikh political party, the Akali Dal, and banned the All India Sikh Students Federation, a large students' union.[324] In addition, the Indian Army conducted operations in the countryside during which thousands of Sikhs, overwhelmingly young men, were detained for interrogation and subsequently tortured.[324]

-

- 1984 anti-Sikh riots 3,350[326] to 17,000[327]

- Operation Woodrose 12,000[328]

- The Parsley massacre was the 1937 mass killing of Haitians in the Dominican Republic on the direct orders of President Rafael Trujillo in order to cleanse Dominica of Haitian migration. After reports of Haitians stealing crops from Dominican residents along the Northern border, Trujillo gave the order to his troops to exterminate all Haitians living in the country's Northern region. The Dominican army then interrogated thousands of civilians demanding that each victim say the word "parsley". If the accused could not pronounce the word to the interrogators satisfaction, they were deemed to be Haitians and shot.[329]These armed forces killed Haitians with rifles, machetes, shovels, knives, and bayonets. Haitian children were reportedly thrown in the air and caught by soldiers' bayonets, then thrown on their mothers' corpses.[330]Some died while trying to flee to Haiti across the Artibonite River, which has often been the site of bloody conflict between the two nations.[331] Survivors who managed to cross the border and return to Haiti told stories of family members being hacked with machetes and strangled by the soldiers, and children bashed against rocks and tree trunks.[332] The use of military units from outside the region was not always enough to expedite soldiers' killings of Haitians. U.S. legation informants reported that many soldiers "confessed that in order to perform such ghastly slaughter they had to get 'blind' drunk."[333](p167) Several months later, a barrage of killings and repatriations of Haitians occurred in the southern frontier.

- The California genocide[335][336] refers to the destruction of individual tribes like the Yuki people during the Round Valley Settler Massacres of 1856–1859,[337] general massacres perpetrated by settlers chasing the gold rush against Indians like the Bloody Island Massacre, or Klamath River "War of Extermination"[338] along with the overall decline of the Indian population of California due to disease and starvation exacerbated by the massacres.

- Queensland represents the single bloodiest colonial frontier in Australia. Thus the records of Queensland document the most frequent reports of shootings and massacres of indigenous people, the three deadliest massacres on white settlers, the most disreputable frontier police force, and the highest number of white victims to frontier violence on record in any Australian colony.[341] Thus some sources have characterized these events as a Queensland Aboriginal genocide.[342][343][344][345]

- The Rohingya genocide[347][348][349][350] against the Rohingya ethnic minority in Myanmar (Burma) by the Myanmar military and Buddhist extremists. The violence began on 25 August 2017 and has continued since, reaching its peak during the months of August and September in 2017. The Rohingya people are a largely Muslim ethnic minority in Myanmar who have faced widespread persecution and discrimination for several decades. They are denied citizenship under the 1982 Myanmar nationality law, and are falsely regarded as Bengali immigrants by much of Myanmar's Bamar majority, to the extent that the government refuses to acknowledge the Rohingya's existence as a valid ethnic group.[351] The Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) is a Rohingya insurgent group that was founded in 2013 to "liberate [the Rohingya] people from dehumanising oppression".[352] On 25 August 2017, ARSA claimed responsibility for coordinated attacks on police posts that reportedly killed twelve security forces. Myanmar's military forces immediately launched a series of retaliatory attacks against Rohingya civilians, and were joined by local Buddhist extremists. Together they burnt down hundreds of Rohingya villages, killed thousands of Rohingya men, women, and children, tortured countless others, and sexually assaulted countless Rohingya women and girls. Several Rohingya refugees say they were forced to witness soldiers throwing their babies into burning houses to die in the fire. Numerous Rohingya refugee women and girls have provided accounts of being brutally gang raped. The violence has resulted in a refugee crisis, with an estimated 693,000 Rohingya fleeing to overcrowded refugee camps in the neighboring country of Bangladesh.

- Decossackization (Russian: Расказачивание, Raskazachivaniye) was the Bolshevik policy of systematic repressions against Cossacks of the Russian Empire, especially of the Don and the Kuban, between 1917 and 1933 aimed at the elimination of the Cossacks as a separate ethnic, political, and economic entity.[355] This was the first example of Soviet leaders deciding to "eliminate, exterminate, and deport the population of a whole territory," which they had taken to calling the "Soviet Vendée"[355] Most authors characterize decossackization as a genocide of the Cossacks,[356][357][358][192][359] a process described by scholar Peter Holquist as part of a "ruthless" and "radical attempt to eliminate undesirable social groups" that showed the Soviet regime's "dedication to social engineering".[360][361]

- The Bosnian genocide comprises localized, in time and place, massacres like in Srebrenica[364] and in Žepa committed by Bosnian Serb forces in 1995, as well as the scattered ethnic cleansing campaign throughout areas controlled by the Army of Republika Srpska[365] during the 1992–95 Bosnian War.[366] Srebrenica marked the most recent act of genocide committed in Europe and was the only theater of that war that fulfilled the definition of genocide as set by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). On 31 March 2010, the Serbian Parliament passed a resolution condemning the Srebrenica massacre and apologizing to the families of Srebrenica for the deaths of Bosniaks ("Bosnian Muslims").[367]

- After the 1966 Nigerian counter-coup during which Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi and Yakubu Gowon seized power, Aguiyi-Ironsi issued a unitary decree abolishing the regionalisation of Nigeria, leading to a series of massacres against the Igbo tribe, who were believed to have conspired to create this decree in order to establish dominion over Nigeria. These massacres were hypothesized to have been organized beforehand,[372] and the Nigerian leadership later began to intentionally promote the extermination of the Igbo. The slaughter lead to the deaths of 8,000 to 30,000 Igbo, and resulted in the secession of Eastern Nigeria into the State of Biafra and the Nigerian Civil War.

- During the Second World War, the Sook Ching, a systematic purge during the Japanese occupation of Singapore and Malaya, was enacted by Imperial Japan to remove hostile elements from the region. Although it mostly targeted those seen as politically dangerous, the Sook Ching also intended to eliminate Hainan people and Chinese-born residents[375] and thus can be considered an act of genocide.

- In Bangladesh, the persecution of the indigenous tribes of the Chittagong Hill Tracts such as the Chakma, Marma, Tripura, Jumma people and others who are mainly Buddhists, Hindus, Christians, and Animists, has been described as genocidal, with Chackmas reportedly the worst affected.[376] [377] [378] [379] [380] The Chittagong Hill Tracts are located bordering India, Myanmar and the Bay of Bengal, and is the home to 500,000 indigenous people. The perpetrators were the Bangladeshi military and the Bengali people of the Chittagong division, who together have burned down Chackma homes, killed many Chakmas, and there were some reports of rape of the indigenous women. There are also accusations of Chakmas being forced to convert to Islam. The conflict started soon after Bangladeshi independence, in 1972 when the Constitution imposed Bengali as the sole official language of the country. Subsequently, the government encouraged and sponsored massive settlement by Bangladeshis in the region, which changed the demographics from 98 percent indigenous in 1972 to fifty percent by 1997. The government allocated a full third of the Bangladeshi military to the region to support Bengali settlers, sparking a protracted guerrilla war between Hill tribes and the military.[377] During this conflict, which officially ended in 1997, a large number of human rights violations against the indigenous peoples have been reported.[381] Amnesty International estimates that up to 90,000 indigenous families were displaced.[382] Following the Chittagong Hill Tracts Peace Accord in 1997, though no further violence have been reported, promised land reforms have only at best been partially fulfilled despite repeated promises by the Bangladeshi government reported Amnesty International in 2013.[382] Chakmas also live in India's Tripura state where a Tripuri separatist movement is going on.[383]

- The 1804 Haiti massacre is considered to be a genocide by many scholars[385][386], as it was intended to destroy the Franco-Haitian population following the Haitian Revolution. The massacre was ordered by King Jean-Jacques Dessalines to remove the remainder of the white population from Haiti, and lasted from January to 22 April 1804. During the massacre, entire families were tortured and killed, and by the end of it, Haiti's white population was virtually non-existent.

- The Selk'nam Genocide was the genocide of the Selk'nam people, indigenous inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego in South America, from the second half of the 19th to the early 20th century. Spanning a period of between ten and fifteen years the Selk'nam, which had an estimated population of some three thousand, saw their numbers reduced to 500.[388]

- The Genocide of Yazidis ' by ISIS includes mass killing, rape and enslavement of girls and women, forced abduction, indoctrination and recruitment of Yazidis boys (aged 7 to 15) to be used in armed conflicts, forced conversion to Islam and expulsion from their ancestral land. The United Nations' Commission of Inquiry on Syria officially declared in its report that ISIS is committing genocide against the Yazidis population.[391] It is difficult to assess a precise figure for the killings[392] but it is known that some thousand of Yazidis men and boys are still unaccounted for and ISIS genocidal actions against Yazidis people are still ongoing, as stated by the International Commission in June 2016.

- The Gukurahundi, the systematic massacre of the Ndebele people by Robert Mugabe's ZANU-PF party, is classified as a genocide by the International Association of Genocide Scholars.[395] The Gukurahundi was initiated because the ZAPU party, the main Zimbabwean opposition party, found the majority of its support among the Ndebele people, leading Mugabe to conclude that they must be exterminated in order to eliminate support for the ZAPU. The Gukurahundi was initiated in 1983, and continued until the signing of the 1987 Unity Accords, during which time about 20, 000 Ndebele where killed and sent to re-education camps.

- The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre (French: Massacre de la Saint-Barthélemy) in 1572 was a targeted group of assassinations and a wave of Catholic mob violence, directed against the Huguenots (French Calvinist Protestants) during the French Wars of Religion. Traditionally believed to have been instigated by Queen Catherine de' Medici, the mother of King Charles IX, the massacre took place a few days after the wedding day (18 August) of the king's sister Margaret to the Protestant Henry III of Navarre (the future Henry IV of France). Many of the most wealthy and prominent Huguenots had gathered in largely Catholic Paris to attend the wedding. The massacre began in the night of 23–24 August 1572 (the eve of the feast of Bartholomew the Apostle), two days after the attempted assassination of Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, the military and political leader of the Huguenots. King Charles IX ordered the killing of a group of Huguenot leaders, including Coligny, and the slaughter spread throughout Paris. Lasting several weeks, the massacre expanded outward to other urban centres and the countryside. Modern estimates for the number of dead across France vary widely, from 5,000 to 30,000. The massacre also marked a turning point in the French Wars of Religion. The Huguenot movement was crippled by the loss of many of its prominent aristocratic leaders, as well as many re-conversions by the rank and file. Those who remained were increasingly radicalized. Though by no means unique, it "was the worst of the century's religious massacres".[398] Throughout Europe, it "printed on Protestant minds the indelible conviction that Catholicism was a bloody and treacherous religion".[399]

- The genocide of the Moriori began in the fall of 1835. The invasions of the Chatham Islands left the Moriori people and their culture to die off. Those who survived were either kept as slaves or eaten and Moriori were not sanctioned to marry other Moriori or have children within their race. This caused their people and their language to be endangered. There were only 101 Moriori people left out of 2000 who had survived in 1863.[401]

- The Conquest of the Desert (Spanish: Conquista del desierto) was a military campaign directed mainly by General Julio Argentino Roca in the 1870s with the intent to establish Argentine dominance over Patagonia, which was inhabited by indigenous peoples. Under General Roca, the Conquest of the Desert extended Argentine power into Patagonia and ended the possibility of Chilean expansion there. The Conquest is highly controversial. Apologists have described the Conquest as bringing civilisation, while revisionists have labelled it a genocide.

- The suppression of the Paraguayan Aché tribe during the military rule of Alfredo Stroessner was called a genocide by observers [411] During Stroessner's rule, the Aché's territory was requisitioned by the state, which destroyed their villages and killed all those who resisted. Many Aché were hacked to death with machetes, and around 85% of the Aché were destroyed.

- The extinction of Aboriginal Tasmanians was called an archetypal case of genocide by Rafael Lemkin[414] (coiner of the word genocide) among other historians, a view supported by more recent genocide scholars like Ben Kiernan who covered it in his book Blood and Soil: A History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. This extinction also includes the Black War, which would make the war an act of genocide.[415] Historians like Keith Windschuttle among other historians disagree with this interpretation in discourse known as the History wars.

References

- "ANALYSIS FRAMEWORK: Genocide" (PDF). Office of the UN Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide (OSAPG). United Nations. p. 1. Retrieved 2019-01-02.

- For a listing of the number of murdered Jews, detailed by country, see Dawidowicz, Lucy (2010). The War Against the Jews: 1933-1945. Open Road Media. Appendix A. ISBN 978-1453203064.

- Rosenfeld, Alvin H. (2008). "The Americanization of the Holocaust". In Moore, Deborah D. (ed.). American Jewish Identity Politics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-02464-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Documenting Numbers of Victims of the Holocaust and Nazi Persecution". Holocaust Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2018-12-06.

- Berenbaum, Michael (2006). The World Must Know: The History of the Holocaust as Told in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. ISBN 978-0-8018-8358-3.

- Zemskov, Viktor N. (2013). "The Extent of human losses USSR in the Great Patriotic War".

- Human losses of the Soviet Union during the second World War. St. Petersburg: Russian Academy of Sciences. 1995. ISBN 978-5-86789-023-0.

-

- "Texts adopted - Thursday, 23 October 2008 - Commemoration of the Holodomor, the artificial famine in Ukraine (1932-1933) - P6_TA(2008)0523". www.europarl.europa.eu.

- "The Artificial Famine/Genocide (Holodomor) in Ukraine 1932–33". InfoUkes. April 26, 2009.

- "Foreign Affairs: Ukrainian Famine (No. 680)" (PDF). Journals of the Senate. 114: 2652–53. 30 October 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 December 2004.

- "Journals of the Senate No.72, 2nd Session, 37th Parliament" (PDF). 19 June 2003: 994–995. Retrieved 24 July 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Columbia declares Holodomor an act of genocide". Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union. 25 December 2007. Archived from the original on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2008.

- "Aprueba resolución: Congreso se solidariza con pueblo Ucraniano" [Resolution passed: Congress is in solidarity with Ukrainian people]. National Congress of Ecuador (in Spanish). 30 October 2007. Archived from the original on 2 November 2007. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

- "International Recognition of the Holodomor". Holodomoreducation.org. 28 November 2006. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- "Sprawozdanie – Komisji Ustawodawczej oraz Komisji Spraw Zagranicznych – o projekcie uchwały w sprawie rocznicy Wielkiego Głodu na Ukrainie" [Report of the Legislative Committee and Foreign Affairs Committee – on the project resolution concerning the anniversary of the Great Famine in Ukraine] (PDF). Senate of the Republic of Poland (in Polish). 14 March 2006. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- "Russian lawmakers reject Ukraine's view on Stalin-era famine". Sputnik International. RIA Novosti. April 2, 2008.

- David Marples (November 30, 2005). "The great famine debate goes on..." ExpressNews. Archived from the original on June 15, 2008.

- Wheatcroft, Stephen G. (2001). "Current knowledge of the level and nature of mortality in the Ukrainian famine of 1931–3" (PDF). In V. Vasil'ev; Y. Shapovala (eds.). Komandiri velikogo golodu: Poizdki V.Molotova I L.Kaganovicha v Ukrainu ta na Pivnichnii Kavkaz, 1932–1933 rr. Kyiv: Geneza.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vallin, Jacques; France Meslé; Serguei Adamets; Serhii Pyrozhkov (2002). "A new estimate of Ukrainian population losses during the crises of the 1930s and 1940s" (PDF). Population Studies. 56 (3): 249–264. doi:10.1080/00324720215934. ISSN 0032-4728. PMID 12553326. Retrieved 13 August 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Meslé, France; Gilles Pison; Jacques Vallin (May 2005). "France-Ukraine: Demographic Twins Separated by History" (PDF). Population and Societies (413): 1–4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 November 2006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Meslé, France; Vallin, Jacques (2003). Mortalité et causes de décès en Ukraine au XXème siècle (in French). Contributions by Vladimir Shkolnikov, Serhii Pyrozhkov, Serguei Adamets. Institut National d'Études Démographiques (INED). ISBN 978-2733201527.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rosefielde, Steven (1983). "Excess Mortality in the Soviet Union: A Reconsideration of the Demographic Consequences of Forced Industrialization, 1929–1949". Soviet Studies. 35 (3): 385–409. doi:10.1080/09668138308411488. JSTOR 151363. PMID 11636006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Наливайченко назвал количество жертв голодомора в Украине [Nalyvaichenko called the number of victims of Holodomor in Ukraine] (in Russian). LB.ua. 14 January 2010. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- Snyder, Timothy (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. London, UK: The Bodley Head. p. 53. ISBN 978-0224081412.

One demographic retrojection suggests a figure of 2.5 million famine deaths for Soviet Ukraine. This is too close to the recorded figure of excess deaths, which is about 2.4 million. The latter figure must be substantially low, since many deaths were not recorded. Another demographic calculation, carried out on behalf of the authorities of independent Ukraine, provides the figure of 3.9 million dead. The truth is probably in between these numbers, where most of the estimates of respectable scholars can be found. It seems reasonable to propose a figure of approximately 3.3 million deaths by starvation and hunger-related disease in Soviet Ukraine in 1932–1933.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Marples, David R. (2007). Heroes and Villains: Creating National History in Contemporary Ukraine. Central European University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-963-7326-98-1. Retrieved 13 August 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Ukraine - The famine of 1932–33". Encyclopædia Britannica.

The Great Famine (Holodomor) of 1932–33—a man-made demographic catastrophe unprecedented in peacetime. Of the estimated six to eight million people who died in the Soviet Union, about four to five million were Ukrainians. ... Its deliberate nature is underscored by the fact that no physical basis for famine existed in Ukraine. ... Soviet authorities set requisition quotas for Ukraine at an impossibly high level. Brigades of special agents were dispatched to Ukraine to assist in procurement, and homes were routinely searched and foodstuffs confiscated... The rural population was left with insufficient food to feed itself.

- Brent Bezo; Stefania Maggi (2015). "Living in "survival mode:" Intergenerational transmission of trauma from the Holodomor genocide of 1932–1933 in Ukraine". Social Science & Medicine. 134: 87–94. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.009. PMID 25931287.

- Raphael Lemkin Papers, The New York Public Library, Manuscripts and Archives Division, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundation, Raphael Lemkin ZL-273. Reel 3. Published in L.Y. Luciuk (ed), Holodomor: Reflections on the Great Famine of 1932–1933 in Soviet Ukraine (Kingston: The Kashtan Press, 2008). Available online Archived 2012-03-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Paul R. Bartrop, Steven Leonard Jacobs (2014). Modern Genocide: The Definitive Resource and Document Collection [4 volumes]: The Definitive Resource and Document Collection. ABC-CLIO. p. 2064. ISBN 9781610693646.

- Davies, Robert; Wheatcroft, Stephen (2004). The Industrialisation of Soviet Russia Volume 5: The Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture 1931–1933. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. xiv. ISBN 978-0-230-27397-9.

- Tauger, Mark B. (2001). "Natural Disaster and Human Actions in the Soviet Famine of 1931–1933". The Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East European Studies (1506): 1–65. doi:10.5195/CBP.2001.89. ISSN 2163-839X.

- Ghodsee, Kristen R. (2014). "A Tale of "Two Totalitarianisms": The Crisis of Capitalism and the Historical Memory of Communism" (PDF). History of the Present. 4 (2): 115–142. doi:10.5406/historypresent.4.2.0115. JSTOR 10.5406/historypresent.4.2.0115.

- "Genocide of Poles During World War II". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2018-12-06.

- Man, John (2004). Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection. New York City: St. Martin's Press. pp. 116–117. ISBN 9780312366247.

- Franke, Herbert and Twitchett, Denis, ed. (1995). The Cambridge History of China: Vol. VI: Alien Regimes & Border States, 907–1368. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pg. 214.

- Mote 1999, pg. 256

- Mote, Frederick W. (1999). Imperial China: 900-1800. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 256–257. ISBN 0674012127.

- Frederick W. Mote (2003). Imperial China 900-1800. Harvard University Press. pp. 256–7. ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7.

- "Doeke Eisma". Chinggis Qan and the Conquest of Eurasia: A Biography. p. 100.

- Kuhn, Dieter (2011-10-15). The Age of Confucian Rule: The Song Transformation of China. p. 50. ISBN 9780674062023.

- Bowman, Rocco (2014). "Bounded Empires: Ecological and Geographic Implications in Sino- Tangut Relations, 960- 1127" (PDF). The Undergraduate Historical Journal at UC Merced. 2: 11.

- McGrath, Michael C. Frustrated Empires: The Song-Tangut Xia War of 1038–44 (150-190. ed.). In Wyatt. p. 153.

- Frey, Rebecca Joyce (2009). Genocide and International Justice. Facts On File. p. 83. ISBN 978-0816073108.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The CGP, 1994–2008 Cambodian Genocide Program, Yale University.

- Terry, Fiona (2002). Condemned to Repeat?: The Paradox of Humanitarian Action. Cornell University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0801487965.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heuveline, Patrick (2001). "The Demographic Analysis of Mortality in Cambodia". In Reed, Holly E.; Keely, Charles B. (eds.). Forced Migration and Mortality. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)