Pacification of Libya

The Pacification of Libya, or the Second Italo-Senussi War,[2] was a long, bloody conflict in Italian Libya between Italian military forces (composed mainly of colonial troops from Libya, Eritrea, and Somalia) and indigenous rebels associated with the Senussi Order. The war lasted from 1923 until 1932,[3][4] when the principal Senussi leader, Omar al-Mukhtar, was captured and executed.[5]

| Pacification of Libya | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Interwar Period | |||||||

Senussi rebel leader Omar Mukhtar (the man in traditional clothing with a chain on his left arm) after his arrest by Italian armed forces in 1931. Mukhtar was executed in a public hanging shortly afterward. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

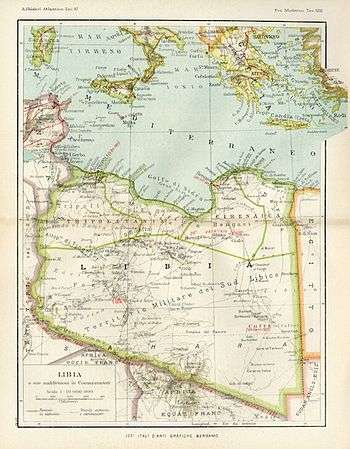

Fighting took place in all of Italian Libya's three provinces (Tripolitania, Fezzan, and Cyrenaica), but was most intense and prolonged in the mountainous Jebel Akhdar region of Cyrenaica.[6] The "pacification" resulted in mass deaths of the indigenous people of Cyrenaica, totaling one quarter of the region's population of 225,000.[7] Italy committed multiple war crimes during the conflict, including the use of chemical weapons, episodes of executing surrendering combatants, and the mass killing of civilians.[1] Italian authorities forcibly expelled 100,000 Bedouin Cyrenaicans, half the population of Cyrenaica, from their settlements, many of which were then given to Italian settlers.[8][9]

Background

Italy had seized military control of Libya from the Ottoman Empire during the Italo-Turkish War in 1912[10] , but the new colony had swiftly revolted, transferring large swathes of territory to local Libyan rule.[11] Conflict between Italy and the Senussis – a Muslim political-religious tariqa based in Libya – erupted into major violence during World War I, when Senussis in Libya began collaborating with the Ottomans against Italian troops. The Libyan Senussis also escalated the conflict with attacks on British forces in Egypt.[12] Warfare between the British and the Senussis continued until 1917.[13]

In 1917 an exhausted Italy signed the Treaty of Acroma, which acknowledged the effective independence of Libya from Italian control.[14] In 1918, Tripolitanian rebels founded the Tripolitanian Republic, though the rest of the country remained under nominal Italian rule.[14] Local agitation against Italy continued, such that by 1920 the Italian government was forced to recognize Senussi leader Sayid Idris as Emir of Cyrenaica and grant him autonomy.[14] In 1922, Tripolitanian leaders offered Idris the position of Emir of Tripolitania;[14] however, before Idris could accept the position, the new Italian government of Benito Mussolini initiated a campaign of reconquest.[14][15]

Since 1911 claims had been made of massacres of Italian soldiers and civilians by Turkish and local Muslim guerrillas, such as a slaughter in Sciara Sciat:[16]

I saw (in Sciara Sciat) in one mosque seventeen Italians, crucified with their bodies reduced to the status of bloody rags and bones, but whose faces still retained traces of their hellish agony. Long rods had been passed through the necks of these wretched men and their arms rested on these rods. They were then nailed to the wall and died slowly with untold suffering. It is impossible for us to paint the picture of this hideous rotted meat hanging pitifully on the bloody wall. In a corner another body was crucified, but as an officer he was chosen to experience refined sufferings. His eyes were stitched closed. All the bodies were mutilated and castrated; so indescribable was the scene and the bodies appeared swollen as shapeless carrion. But that's not all! In the cemetery of Chui, which served as a refuge from the Turks and to whence soldiers retreated from afar, we could see another show. In front of one door near the Italian trenches five soldiers had been buried up to their shoulders, their heads emerged from the black sand stained with their blood: heads horrible to see and there you could read all the tortures of hunger and thirst. –– Gaston Leroud, correspondent for Matin-Journal (1917)[17]

Reports of these massacres led to cries for retaliation and revenge in Italy, and in the early 1920s the rise to power of Benito Mussolini, leader of the National Fascist Party, as Prime Minister of Italy led to a much more aggressive approach to foreign policy. Given the importance that the Fascists gave to Libya as part of a new Italian Empire, this incident served as a useful pretext for large-scale military action to reclaim it.[18]

The Pacification Campaign

The Pacification Campaign began with Italian forces rapidly occupying the Sirte desert separating Tripolitania from Cyrenaica. Using aircraft, motor transport, and good logistical organization, the Italians were able to occupy 150,000 square kilometres (58,000 sq mi) of territory in five months,[19] cutting off the physical connection formerly held by the rebels between Cyrenaica and Tripolitania.[19] By late 1928 the Italians had taken control of Ghibla, and its tribes were disarmed.[19]

From 1923 to 1924, Italian troops regained all territory north of the Ghadames-Mizda-Beni Ulid region, with four-fifths of the estimated population of Tripolitania and Fezzan within the Italian area. In this period they also regained the northern lowlands of Cyrenaica,[15] but attempts to occupy the forested hills of Jebel Akhtar were met with strong guerrilla resistance, led by Senussi sheikh Omar Mukhtar.[15]

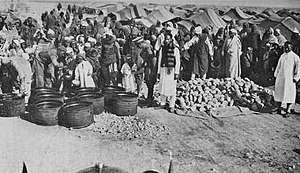

Attempted negotiations between Italy and Omar Mukhtar broke down and Italy then planned for the complete conquest of Libya.[20] In 1930, Italian forces conquered Fezzan and raised the Italian flag in Tummo, the southernmost region of Fezzan.[19] On 20 June 1930, Pietro Badoglio wrote to General Graziani: "As for overall strategy, it is necessary to create a significant and clear separation between the controlled population and the rebel formations. I do not hide the significance and seriousness of this measure, which might be the ruin of the subdued population...But now the course has been set, and we must carry it out to the end, even if the entire population of Cyrenaica must perish".[21] By 1931, well over half of the population of Cyrenaica were confined to 15 concentration camps where many died as result of overcrowding together with a lack of water, food and medicine while Badoglio had the Air Force use chemical warfare against the Bedouin rebels in the desert.[21]

12,000 Cyrenaicans were executed in 1931 and all the nomadic peoples of northern Cyrenaica were forcefully removed from the region and relocated to huge concentration camps in the Cyrenaican lowlands.[20] Italian military authorities carried out the forced migration and deportation of the entire population of Jebel Akhdar in Cyrenaica, resulting in 100,000 Bedouins, half the population of Cyrenaica, being expelled from their settlements.[9] These 100,000 people, mostly women, children, and the elderly, were forced by Italian authorities to march across the desert to a series of barbed-wire concentration camp compounds erected near Benghazi, while stragglers who could not keep up with the march were summarily shot by Italian authorities.[22] Propaganda by the Fascist regime declared the camps to be oases of modern civilization that were hygienic and efficiently run - however in reality the camps had poor sanitary conditions as the camps had an average of about 20,000 Beduoins together with their camels and other animals, crowded into an area of 1 square kilometre (0.39 sq mi).[22] The camps held only rudimentary medical services, with the camps of Soluch and Sisi Ahmed el Magrun with 33,000 internees each having only one doctor between them.[22] Typhus and other diseases spread rapidly in the camps as the people were physically weakened by meagre food rations provided to them and forced labour.[22] By the time the camps closed in September 1933, 40,000 of the 100,000 total internees had died in the camps.[22]

To close rebel supply routes from Egypt, the Italians constructed a 300-kilometre (190 mi) barbed wire fence on the border with Egypt that was patrolled by armoured cars and aircraft.[20] The Italians persecuted the Senussi Order; zawias and mosques were closed, Senussi practices were forbidden, Senussi estates were confiscated, and preparations were made for Italian conquest of the Kufra Oasis, the last stronghold of the Senussi in Libya.[20] In 1931, Italian forces seized Kufra where Senussi refugees were bombed and strafed by Italian aircraft as they fled into the desert.[20] Mukhtar was captured by the Italians in 1931, followed by a court martial and his public execution by hanging at Suluq.[20]

Mukhtar's death effectively ended the resistance, and in January 1932, Badoglio proclaimed the end of the Pacification of Libya.[24]

Takeover of Kufra

The Frankfurter Zeitung reporter and author Muhammad Asad interviewed a man from Kufra after its seizure by the Italians in his book The Road to Mecca.

"How did Kufra fall?"

With a weary gesture, Sidi Umar motioned to one of his men to come closer: "Let this man tell thee the story...He is one of the few who have escaped from Kufra. He came to me only yesterday." The man from Kufra sat down on his haunches before me and pulled his ragged burnus around him. He spoke slowly, without any tremor of emotion in his voice; but his gaunt face seemed to mirror all the horrors he had witnessed.

"They came upon us in three columns, from three sides, with many armoured cars and heavy cannon. Their aeroplanes came down low and bombed houses and mosques and palm groves. We had only a few hundred men able to carry arms; the rest were women and children and old men. We defended house after house, but they were too strong for us, and in the end only the village of Al-Hawari was left to us. Our rifles were useless against their armoured cars; and they overwhelmed us. Only a few of us escaped. I hid myself in the palm orchards waiting for a chance to make my way through the Italian lines; and all through the night I could hear the screams of the women as they were being raped by the Italian soldiers and Eritrean askaris. On the following day an old woman came to my hiding place and brought me water and bread. She told me that the Italian general had assembled all the surviving people before the tomb of Sayyid Muhammad al-Mahdi; and before their eyes he tore a copy of the Koran into pieces, threw it to the ground and set his boot upon it, shouting, "Let your beduin prophet help you now, if he can!" And then he ordered the palm trees of the oasis to be cut down and the wells destroyed and all the books of Sayyid Ahmad's library burned. And on the next day he commanded that some of our elders and ulama [scholars] be taken up in an aeroplane - and they were hurled out of the plane high above the ground to be smashed to death...And all through the second night I heard from my hiding place the cries of our women and the laughter of the soldiers, and their rifle shots...At last I crept out into the desert in the dark of night and found a stray camel and rode away..."

— Muhammad Asad, The Road to Mecca

War crimes

Both the Senussi and the Italian armed forces were accused of committing numerous war crimes.

Specific war crimes committed by the Italian armed forces against civilians include deliberate bombing of civilians, killing unarmed children, women, and the elderly, rape and disembowelment of women, throwing prisoners out of aircraft to their death and running over others with tanks, regular daily executions of civilians in some areas, and bombing tribal villages with mustard gas bombs beginning in 1930.[25]

The Senussi were accused by Italian sources of refusing to take prisoners from the Italian armed forces and torture including mutilation of Italian soldiers before death.[26]

Aftermath

In 2008, Italy and Libya reached agreement on a document compensating Libya for damages caused by Italian colonial rule. Muammar Gaddafi, Libya's ruler at the time, attended the signing ceremony wearing a historical photograph on his uniform that showed Cyrenaican rebel leader Omar Mukhtar in chains after being captured by Italian authorities during the Pacification. At the ceremony, Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi declared: "In this historic document, Italy apologizes for its killing, destruction and repression of the Libyan people during the period of colonial rule." He went on to say that this was a "complete and moral acknowledgement of the damage inflicted on Libya by Italy during the colonial era."[27]

These declarations received harsh criticism from the Associazione Rifugiati Italiani dalla Libia and from some Italian historians, who felt the agreement was "based on false assumptions created by Gaddafi propaganda".[28]

Film portrayals

The 1981 film Lion of the Desert by Moustapha Akkad is about this conflict.

See also

References

- Duggan, Christopher (2007). The Force of Destiny: A History of Italy Since 1796. New York: Houghton Mifflin. p. 497.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cooper, Tom; Grandolini, Albert (19 January 2015). Libyan Air Wars: Part 1: 1973-1985. Helion and Company. p. 5. ISBN 9781910777510.

- Nina Consuelo Epton, Oasis Kingdom: The Libyan Story (New York: Roy Publishers, 1953), p. 126.

- Stewart, C. C. (1986). "Islam". The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 7: c. 1905 – c. 1940 (PDF). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 196. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 August 2017.

- Detailed description of some fights (in Italian)

- The Second Italo-Senussi War http://countrystudies.us/libya/21.htm retrvd 2-1-20

- Mann, Michael (2006). The Dark Side of Democracy: Explaining Ethnic Cleansing. Cambridge University Press. p. 309. ISBN 9780521538541.

- Cardoza, Anthony L. (2006). Benito Mussolini: the first fascist. Pearson Longman. p. 109.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (2010). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 358.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Antonio De Martino.Tripoli italiana Societa Libraria italiana (Library of Congress). New York, 1911

- Wright, John (1983). Libya: A Modern History. Kent, England: Croom Helm. p. 30.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ian F. W. Beckett. The Great War: 1914-1918. Routledge, 2013. P188.

- Adrian Gilbert. Encyclopedia of Warfare: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Routledge, 2000. P221.

- Melvin E. Page. Colonialism. Santa Barbara, California, USA: ABC-CLIO, 2003. P749.

- Wright 1983, p. 33

- Italo-turkish war: Sciara Sciat and the massacre of Italians

- Gaston Leroud , Matin Journal edition August 23, 1917

- Wright, John (1983). Libya: A Modern History. Kent, England: Croom Helm. pp. 32–33.

- Wright 1983, p. 34

- Wright 1983, p. 35

- Grand 2004, p. 131

- Duggan 2007, p. 496

- David Miller, Chris Foss. Great Book of Tanks: The World's Most Important Tanks from World War I to the Present Day. Zenith Imprint, 2003. p. 83.

- Wright 1983, pp. 35–36

- Geoff Simons, Tam Dalyell (British Member of Parliament, forward introduction). Libya: the struggle for survival. St. Martin's Press, 1996. 1996 Pp. 129.

- Rodolfo Graziani. "Ho servito la Patria" p. 18-39

- Oxford Business Group (2008). The Report: Libya 2008. p. 17.

- Critics to Berlusconi apologies (in Italian)

Books and articles

- Grand, Alexander de "Mussolini's Follies: Fascism in Its Imperial and Racist Phase, 1935-1940" pages 127-147 from Contemporary European History, Volume 13, No. 2 May 2004.