Genocide Convention

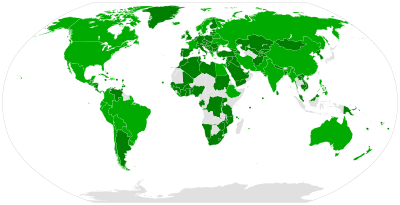

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was unanimously adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 9 December 1948 as General Assembly Resolution 260.[1] The Convention entered into force on 12 January 1951.[2] It defines genocide in legal terms, and is the culmination of years of campaigning by lawyer Raphael Lemkin.[3] All participating countries are advised to prevent and punish actions of genocide in war and in peacetime. As of May 2019, 152 states have ratified or acceded to the treaty, most recently Mauritius on 8 July 2019.[4] One state, the Dominican Republic, has signed but not ratified the treaty.

Long name:

| |

|---|---|

| Signed | 9 December 1948 |

| Location | Paris |

| Effective | 12 January 1951 |

| Signatories | 39 |

| Parties | 152 (complete list) |

| Depositary | Secretary-General of the United Nations |

Definition of genocide

Article 2 of the Convention defines genocide as

... any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

- (a) Killing members of the group;

- (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

— Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Article 2[5]

Article 3 defines the crimes that can be punished under the convention:

- (a) Genocide;

- (b) Conspiracy to commit genocide;

- (c) Direct and public incitement to commit genocide;

- (d) Attempt to commit genocide;

- (e) Complicity in genocide.

— Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Article 3[5]

The convention was passed to outlaw actions similar to the Holocaust by Nazi Germany during World War II. The first draft of the Convention included political killings, but the USSR[6] along with some other nations would not accept that actions against groups identified as holding similar political opinions or social status would constitute genocide,[7] so these stipulations were subsequently removed in a political and diplomatic compromise.

Parties

Provision granting immunity from prosecution for genocide without its consent were made by Bahrain, Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, the United States, Vietnam, Yemen, and Yugoslavia.[8][9] Prior to the United States Senate's ratification of the convention, Senator William Proxmire spoke in favor of the treaty to the Senate every day it was in session between 1967 and 1986.

Reservations

Immunity from prosecutions

Persons charged with genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in article III shall be tried by a competent tribunal of the State in the territory of which the act was committed, or by such international penal tribunal as may have jurisdiction with respect to those Contracting Parties which shall have accepted its jurisdiction.

— Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Article 6[5]

Any Contracting Party may call upon the competent organs of the United Nations to take such action under the Charter of the United Nations as they consider appropriate for the prevention and suppression of acts of genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in article III.

— Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Article 8[5]

Disputes between the Contracting Parties relating to the interpretation, application or fulfilment of the present Convention, including those relating to the responsibility of a State for genocide or for any of the other acts enumerated in article III, shall be submitted to the International Court of Justice at the request of any of the parties to the dispute.

— Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Article 9[5]

Application to Non-Self-Governing Territories

Any Contracting Party may at any time, by notification addressed to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, extend the application of the present Convention to all or any of the territories for the conduct of whose foreign relations that Contracting Party is responsible

— Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Article 12[5]

Several countries opposed this article, considering that the convention should apply to Non-Self-Governing Territories:

The opposition of those countries were in turn opposed by:

Breaches

Iraq

In 1988, following the campaign of chemical weapons attacks and mass killings of Kurdish persons in northern Iraq, legislation was proposed to the United States House of Representatives, in the, "Prevention of Genocide Act". The bill was defeated to allegations of "inappropriate terms" such as "genocide". Contemporary scholars and international organizations widely consider the Anfal Campaign to have been genocide following the Iran-Iraq war, killing tens of thousands of Kurds. Saddam Hussein was charged individual with genocide though executed prior to a return for the charge. Associates of Hussein such as "Chemical Ali", and others have been widely accused of genocide and the events widely cited as one of the atrocities most commonly associated with the Hussein regime.[10]

Rwanda

The first time that the 1948 law was enforced occurred on 2 September 1998 when the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda found Jean-Paul Akayesu, the former mayor of a small town in Rwanda, guilty of nine counts of genocide. The lead prosecutor in this case was Pierre-Richard Prosper. Two days later, Jean Kambanda became the first head of government to be convicted of genocide.

The Former Yugoslavia

The first state and parties to be found in breach of the Genocide convention was Serbia and Montenegro, and numerous Bosnian Serb leaders. In the Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Serbia and Montenegro case the International Court of Justice presented its judgment on 26 February 2007. It cleared Serbia of direct involvement in genocide during the Bosnian war. International Tribunal findings, have addressed two allegations of genocidal events, including the 1992 Ethnic Cleansing Campaign in municipalities throughout Bosnia, as well as the convictions found in regards to the Srebrenica Massacre of 1995 in which the tribunal found, "Bosnian Serb forces committed genocide, they targeted for extinction, the 40,000 Bosnian Muslims of Srebrenica ... the trial chamber refers to the crimes by their appropriate name, genocide ...". Individual convictions applicable to the 1992 Ethnic Cleansings have not been secured however. A number domestic courts and legislatures have found these events to have met the criteria of genocide, and the ICTY found the acts of, and intent to destroy to have been satisfied, the "Dolus Specialis" still in question and before the MICT, UN war crimes court.[11][12] but ruled that Belgrade did breach international law by failing to prevent the 1995 Srebrenica genocide, and for failing to try or transfer the persons accused of genocide to the ICTY, in order to comply with its obligations under Articles I and VI of the Genocide Convention, in particular in respect of General Ratko Mladić.[13][14]

Situations under investigation

The United Nations Security Council is the organization entitled to mandate the International Criminal Court with investigations relating to breaches of the genocide convention.[15]

As of 2018, the case relating to Darfur, Sudan, opened in 2005, is the only pending investigation that is genocide-related. Warrants to arrest Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir, former president of Sudan, were issued in 2009 and 2010. The case remains in the pre-trial stage as the suspect is still at large.[16]

Other accusations

United States

One of the first accusations of genocide submitted to the UN after the Convention entered into force concerned treatment of Black Americans. The Civil Rights Congress drafted a 237-page petition arguing that even after 1945, the United States had been responsible for hundreds of wrongful deaths, both legal and extra-legal, as well as numerous other genocidal abuses. Leaders from the Black community, including William Patterson, Paul Robeson, and W. E. B. DuBois presented this petition to the UN in December 1951.[17] However, this accusation was a domestic political act by the Civil Rights Congress, without any reservations that a formal charge would be levied against the U.S.

See also

References

- "Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide" (PDF). United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- "Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide". United Nations Treaty Series. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- Auron, Yair, The Banality of Denial, (Transaction Publishers, 2004), 9.

- "United Nations Treaty Collection". Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- Text of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, website of the UNHCHR.

- Robert Gellately & Ben Kiernan (2003). The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in Historical Perspective. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 267. ISBN 0-521-52750-3.

where Stalin was presumably anxious to avoid his purges being subjected to genocidal scrutiny.

- Staub, Ervin. The Roots of Evil: The Origins of Genocide and Other Group Violence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-521-42214-0.

- Prevent Genocide International: Declarations and Reservations to the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

- United Nations Treaty Collection: Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide Archived 20 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, STATUS AS AT: 1 October 2011 07:22:22 EDT

- Dave Johns. "FRONTLINE/WORLD . Iraq - Saddam's Road to Hell - A journey into the killing fields . PBS". www.pbs.org.

- Chambers, The Hague. "ICTY convicts Ratko Mladić for genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity | International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia". www.icty.org.

- Hudson, Alexandra (26 February 2007). "Serbia cleared of genocide, failed to stop killing". Reuters.

- "ICJ:Summary of the Judgment of 26 February 2007 – Bosnia v. Serbia". Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2008.

- Court Declares Bosnia Killings Were Genocide The New York Times, 26 February 2007. A copy of the ICJ judgement can be found here Archived 28 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Listing of genocide cases pending at the ICC". International Criminal Court (ICC). Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "Al Bashir Case, The Prosecutor v. Omar Hassan Ahmad Al Bashir, ICC-02/05-01/09". International Criminal Court (ICC). Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- John Docker, "Raphaël Lemkin, creator of the concept of genocide: a world history perspective", Humanities Research 16(2), 2010.

Further reading

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Tams, Christian J.; Berster, Lars; Schiffbauer, Björn (2014). Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide – A Commentary, C.H. Beck / Nomos / Hart Publishing, ISBN 978-3-4066-0317-4

- Henham, Ralph J.; Chalfont, Paul; Behrens, Paul (Editors 2007). The criminal law of genocide: international, comparative and contextual aspects, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 0-7546-4898-2, ISBN 978-0-7546-4898-7 p. 98

- Weiss-Wendt, Anton (2017). The Soviet Union and the Gutting of the UN Genocide Convention. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-31290-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Introductory note by William Schabas and procedural history note on the Genocide Convention in the Historic Archives of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law