Kazakh Khanate

The Kazakh Khanate, (Kazakh: Қазақ Хандығы, Qazaq Handyǵy, قازاق حاندىعى) was a successor of the Golden Horde existing from the 15th to 19th century, located roughly on the territory of the present-day Republic of Kazakhstan. At its height, the khanate ruled from eastern Cumania (modern-day West Kazakhstan) to most of Uzbekistan, Karakalpakstan and the Syr Darya river with military confrontation as far as Astrakhan and Khorasan Province, which are now in Russia and Iran, respectively. The Khanate also engaged in slavery and raids in its neighboring countries of Russia and Central Asia, and was later weakened by a series of Oirat and Dzungar invasions. These resulted in a decline and further disintegration into three Jüz-es, which gradually lost their sovereignty and were incorporated to the expanding Russian Empire. Its establishment marked the beginning of Kazakh statehood[1] whose 550th anniversary was celebrated in 2015.[2]

Kazakh Khanate Қазақ Хандығы Qazaq Handyǵy قازاق حاندىعى | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1465–1848 | |||||||||

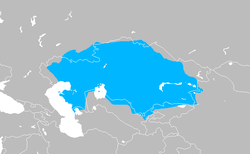

Kazakh Khanate in around 18th century with modern borders | |||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||

| Common languages | Kazakh language | ||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Khan | |||||||||

• 1465–1480 | Janibek Khan Kerei Khan (first) | ||||||||

• 1841–1847 | Kenesary Khan (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1465 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1848 | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1800 | 2.5 million | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Kazakhstan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ancient | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Khanates | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Colonization and post-nomadic period | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Topics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

History

In 1227, a proto-Kazakh state was formed within the Golden Horde in the steppe, which was the White Horde. After its separation from the Golden Horde in 1361, the White Horde became an independent state for a certain period of time, sometimes uniting with the Blue Horde to reestablish the Golden Horde. However, after the death of Khan of the Golden Horde, Barak Khan in 1428 the Golden Horde became fragmented, and the White Horde itself was divided into the Uzbek Khanate and the Nogai Horde while the remaining land was divided between Mustafa Khan in the south and Mohammed Khan in the north. The Uzbek Khanate, which dominated most of present-day Kazakhstan, was ruled by Abu'l-Khayr Khan who conspired in killing Barak Khan. Under Abu’l-Khayr Khan's leadership, the Uzbek Khanate became a corrupt, unstable, and weak state that often dealt internal problems. To make matters worse, the khanate itself was raided by Oirats who pillaged nomadic settlements and major cities where they were looted, damaged, and had civilians massacred. Peace was made in 1457 between the Uzbeks and the Oirats where Abu’l-Khayr Khan suffered a severe defeat which made him lose reputation among the Uzbeks.

Formation

The formation of the Kazakh Khanate began in 1459, when several Uzbek tribes dissatisfied with Abu’l-Khayr's rule, led by two sons of Barak Khan, Janibek and Kerei, fled the Uzbek Khanate in an event known as the Great Migration. The two brothers led the nomads towards Moghulistan, eventually settling and establishing an independent state. The new khanate soon became a buffer state between the Moghulistan and the Uzbek Khanate. Although both Janibek Khan and Kerei Khan were considered the founding rulers of the Kazakh Khanate, it was Janibek Khan who initially wielded the most power. Eager to liberate his land from Abu’l Khayr Khan, Janibek invaded the Uzbek Khanate in 1468. Abu’l Khayr, in response, launched a campaign against the Kazakhs, but died on his way to Zhetysu. Upon the death of Kerei Khan in 1473/4 Janibek Khan became the sole ruler.

The early years of the Kazakh Khanate were marked by struggles for control of the steppe against the Abu'l-Khayr's grandson, Muhammad Shaybani. In 1470, the Kazakhs defeated Shaybani at the city of Iasy (present-day Turkistan), forcing the Uzbeks to retreat south to Samarkand and Bukhara.

In 1480 Kerei Khan's son Burunduk became khan. During his reign, the Kazakhs were able to muster an army of 50,000 men and to repeatedly defeat the forces of Muhammad Shaybani along the Syr Darya river. It was during his reign, that the Uzbeks concluded peace with the Kazakhs in 1500, thus giving all the former Uzbek Khanate lands in the north of Syr Darya to the Kazakh Khanate.

Expansion of the Kazakh Khanate

Kasym, son of Janibek, became the Khan in 1511. Under his rule, the Kazakh Khanate reached its greatest strength so much that the Nogai Horde, which occupied the territory of modern Western Kazakhstan, became its number one enemy. Kasym successfully captured the Nogai capital Saray-Juk in 1520, pushing the Nogai Horde to the Astrakhan Khanate. Under Kasym Khan, the borders of the Kazakh Khanate expanded, the population reached 1 million people. It was during the reign of Kasym Khan that the Kazakh Khanate gained fame and political weight in the modern Euro-Asian arena. The first major state to establish diplomatic relations with the Kazakh Khanate was the Tsardom of Russia. Since then, the Kazakh Khanate seen as a new political entity to the Western Europe.

Kasym Khan also instituted the first Kazakh code of laws in 1520, called "Қасым ханның қасқа жолы" (transliterated, "Qasım xannıñ qasqa jolı" — "Bright Road of Kasym Khan"). Kasym Khan also ratified his alliance with the Timurid leader Babur, particularly after the fall of the Shaybanids, and was thus praised by the Mughals and the populace of Samarqand.

Turmoil and civil war

After the death of Kasym Khan, the Nogaiys restored their status quo by capturing the territory before in the west of the Turgai River. The Kazakh Khanate itself focused on the territory of Zhetysu and South Kazakhstan, where a strife was starting to happen. The central territory of Kazakhstan, Sary-Arka, at that time was nominally part of the Kazakh Khanate. The Khanate of Sibir seized the northern regions of Sary-Arka.

Under Taiyr Khan, the Oirats invaded and captured eastern parts of Sary Arka in the 1520s.

In the early 1530s, a civil war began in the Kazakh Khanate between the grandsons of Janibek Khan. Haqnazar Khan emerged as victories and reunited the khanate under his control.

Haqnazar Khan (1537–1580)

Under Haqnazar Khan, also known as Haq-Nazar or Khaknazar Khan[3] or Ak Nazar Khan,[4] the Kazakh Khanate faced competition from several directions: the Nogai Horde in the west, the Khanate of Sibir in the north, Moghulistan in the east and the Khanate of Bukhara in the south.

Haqnazar Khan began to liberate the occupied Kazakh lands. He returned the northern regions of Sary-Arka to the Kazakh Khanate. Having begun a campaign against the Nogai Horde, Haqnazar reconquered Saraishyk from the Nogai Horde and the surrounding Kazakh territories as well. In the fight against the Khivans, the Kazakhs conquered the Mangyshlak peninsula and successfully repelled the Oirats. Haqnazar began a campaign against Moghulistan with the aim of finally incorporating Zhetysu into the Kazakh Khanate. The campaign ended successfully and resulted in defeat for Moghulistan. However, in the north, there was a threat from the Khanate of Sibir, led by Khan Kuchum.

In 1568, the Kazakhs successfully defeated the Nogai Horde at the Emba River and reached Astrakhan, but were repelled by Russian forces.[3][5][6]

Shygai Khan (1580–1582)

Tauekel Khan (1582–1598)

Tauekel Khan expanded control of the Kazakh Khanate over Tashkent, Fergana, Andijan and Samarkand. In 1598, Kazakh forces approached Bukhara and besieged it for 12 days, but afterwards the Bukharan leader Pir-Muhammad and reinforcements under the command of his brother Baki-Muhammad pushed back the Kazakhs. In that battle, Tauekel Khan was wounded and died during the retreat back to Tashkent.

Esim Khan (1598–1628)

After the death of Tauekel Khan came Esim Sultan, son of Sheehan Khan. His reign was the time of the next (third) strengthening of the Kazakh Khanate after Kasim Khan and Khak-Nazar Khan. Esim Khan moved the capital of the khanate to Sygnak in Turkestan and suppressed the revolts of the Karakalpaks.

There followed a 15-year period of calm between the Kazakh Khanate and the Khanate of Bukhara.

Esim Khan established peace with the Khanate of Bukhara and returned control of Samarkand to them. However, Bukhara was still bitter about the loss of Tashkent, which led to additional conflicts. Starting in 1607, the Khanate of Bukhara engaged in several battles and eventually obtained control of Tashkent.

Esim Khan united the Kazakh army and began a campaign against the Tashkent Khan Tursun Muhammad and Khan of Bukhara. In 1627, he defeated the enemy. Esim Khan abolished the Tashkent Khanate and the war finally ended.

Salqam-Jangir Khan (1629–1680)

During Salqam-Jangir Khan's reign, a new and powerful rival of the Kazakhs appeared in the east, known as the Zunghar Khanate. The Zunghar had recently converted to Mahayana Buddhism and their Erdeni Batur believed he could reestablish the 13th-century empire of Genghis Khan. However, much had changed since the days of the Mongol Empire, and the Kazakhs, like the Kirghiz and the Tatars, had almost entirely converted to Islam under the authority of Emir Timur, who also reestablished new centers of power such as Samarqand and Bukhara, which had greatly influenced the founding of the Kazakh Khanate.

In 1652, the Zunghar leader Erdeni Batur attempted to eliminate the Kazakh Khanate and its inhabitants; he dispatched more than 50,000 Zunghar warriors against the Kazakh Khanate, which refused to submit to him. The early stages of the Kazakh-Dzungar Wars took place in the Altai Mountains and later battles were fought on the vast steppes. Unable to halt the advance of the Zunghars, the Kazakh Ghazis and their leader Salqam-Jangir Khan's forces were defeated. Unfortunately in the year 1680, Salqam-Jangir Khan died in battle, protecting his people against the Zunghars.

Tauke Khan (1680–1718)

Tauke Khan was elected as the leader of the Kazakh Khanate immediately after the death of Salqam-Jangir Khan, and he led the battered Kazakh warriors across the steppes to resist the advance of the Zunghars. Unfortunately, the already weakened Kazakhs were once again faced with defeat at Sayram and soon lost many major cities to the Zunghars.

Tauke Khan soon sought alliances with the Kirghiz in the southeast who were also facing a Zunghar invasion in their Issyk-Kul Lake region and even the Uyghurs of the Tarim Basin. In 1687, Zunghars besieged Hazrat-e Turkestan and were forced to retreat after the arrival of Subhan Quli Khan.

In 1697, Tsewang Rabtan became the leader of the Zunghar Khanate, and he dispatched several of his commanders to subjugate Tauke Khan and many major wars between the Zunghars and the Kazakh Khanate continued into the following years: 1709, 1711—1712, 1714 and 1718. The Kazakh Khanate had indeed been weakened by the confrontation and nearly one-third of their population had been lost by the ensuing conflict. With Tauke Khan's death in 1718, the Kazakh Khanate splintered into three Jüz — the Great jüz, the Middle jüz and the Little jüz. Each Jüz had its own Khan from this time onward.

Tauke Khan is also known for refining the Kazakh code of laws, and reissuing it under the title "Жеті Жарғы" (transliterated, "Jeti Jarği"—"Seven Charters").

Ablai Khan (1771–1781)

Ablai Khan was a khan of the Middle jüz or Horde who managed to extend his control over the other two jüzes to include all of the Kazakhs. Before he became khan, Ablai participated in Kazakh-Dzungar Wars and proved himself a talented organizer and commander. He led numerous campaigns against the Kokand Khanate and the Kyrgyz. In the latter campaign, his troops liberated many cities in Southern Kazakhstan and even captured Tashkent. During his actual reign, Ablai Khan did his best to keep Kazakhstan as independent as possible from the encroaching Russian Empire and the Chinese Qing dynasty. He employed a multi-vector foreign policy to protect the tribes from Chinese and Dzungar aggressors. He also sheltered the Dzungar Oirat taishas Amursana and Dawachi from attacks by the Khoshut-Orait King of Tibet, Lha-bzang Khan, as the Dzungar Khanate fractured following the death of Galdan Tseren in 1745. However, once Amursana and Dawachi were no longer allies, Ablai Khan took the opportunity to capture herds and territory from the Dzungars.[7]

Kenesary Khan (1841–1847)

Kenesary was the last Kazakh Khan, and the leader of national liberation movement that resisted the capture of Kazakh lands and segregation policies by the Russian Empire. He was the grandson of Ablai Khan and is largely regarded as the last ruler of the Kazakh Khanate.

By the mid 19th century, the Kazakhs fell under the full control of the Russian Empire and were banned from electing their own leader or even given representation in the empire's legislative structures. All fiscal/tax collections were also taken away from local Kazakh representatives and given to Russian administrators. Kenesary Khan fought against the Russian imperial forces until his death in 1847.

In 1841, at an all-Kazakh Kurultai, Kenesary was elected as Khan (supreme leader) by all Kazakh representatives. The ceremony of coronation followed all Kazakh traditions.

As a freedom fighter and popular as a leading voice against the increasingly aggressive and forceful policies of the Russian Empire, Kenesary was ruthless in his actions and unpredictable as a military strategist. By 1846, however, his resistance movement had lost momentum as some of his rich associates had defected to the Russian Empire, having been bribed and been promised great riches. Betrayed, Kenesary Khan grew increasingly suspicious of the remaining members of the Resistance, possibly further alienating them. In 1847, the Khan of the Kazakhs met his death in Kyrgyz lands during his assault on northern Kyrgyz tribes. He was executed by Ormon Khan, the Kyrgyz khan who was subsequently rewarded by the Russians with a larger estate and an official administrative role. Kenesary Khan's head was cut off and sent to the Russians.

Over the last decade, Kenesary Khan has been increasingly regarded as a hero in Kazakh literature and media. Kenesary Khan can be seen on the shore of the river Esil in the capital of Kazakhstan, Nur-Sultan.

Disintegration of Khanate and Russian conquest

Gradual decline, disintegration and accession of Kazakh territories into the Russian Empire began in the mid-18th and ended in the second part of the 19th century. By the mid-18th century, as a result of long-lasting armed conflicts with Dzungars and Oirats, the Kazakh Khanate had started to decline and further disintegrate into three Jüzes, which formerly constituted the Kazakh Khanate in a confederate form.

By the mid-19th century some tribes of the Middle Jüz started war with the Russian occupiers. However, the process was long and filled with many minor and major armed conflicts and resistance.

Russian colonial policies/strategies brought military fortresses, many settlements, and externally imposed rules into Kazakh lands. A series of laws were introduced by the Russian Empire, abolishing local indigenous government in the form of Khan rule, instituting segregationist settlement policies, etc., resulting in numerous uprisings against colonial rule. Significant resistance movements were led by leaders such as Isatay Taymanuly (1836–1837), Makhambet Utemisuly (1836–1838) and Eset Kotibaruli (1847–1858).

Meanwhile, the Senior Jüz sided with the Emirate of Bukhara and the Khanate of Kokand from the south, and started opposing the expansion of the Russian Empire.

Full Russian rule over all Kazakh lands was established in the second half of the 19th century, after the southern towns of Aq-Meshit, Shymkent, Aulie-Ata and others were taken by the Russian Imperial Army.

Slavery

By the mid 18th century, the Russian Empire had expanded into Siberia, and Russian settlements started to appear along the Volga and Yaik rivers. The Kazakh-Russian relationship at the border regions was tense, which often resulted in mutual raids by Russian Cossacks on Kazakh lands and Kazakhs on Russian settlements.

Kazakh Khanate slave trade on Russian settlement

During the 18th century, raids by Kazakhs on Russia's territory of Orenburg were common; the Kazakhs captured many Russians and sold them as slaves in the Central Asian market. The Volga Germans were also victims of Kazakh raids; they were ethnic Germans living along the River Volga in the region of southeastern European Russia around Saratov.

In 1717, 3,000 Russian slaves, men, women, and children, were sold in Khiva by Kazakh and Kyrgyz tribesmen.[8]

In 1722, they stole cattle, robbed from Russian villages and people trapped in captivity and sold in the slave markets of Central Asia (in 1722 in Bukhara were over 5,000 Russian prisoners). In the middle of the 17th century, 500 Russians were annually sold to Khiva by Kazakhs.

In 1730, the Kazakhs' frequent raids into Russian lands were a constant irritant and resulted in the enslavement of many of the Tsar's subjects, who were sold on the Kazakh steppe.[9]

In 1736, urged on by Kirilov, the Kazakhs of the Lesser and Middle Hordes launched raids into Bashkir lands, killing or capturing many Bashkirs in the Siberian and Nogay districts.[10]

In 1743, an order was given by the senate in response to the failure to defend against the Kazakh attack on a Russian settlement, which resulted in 14 Russians killed, 24 wounded. In addition, 96 Cossacks were captured by Kazakhs.[11]

In 1755, Nepliuev tried to enlist Kazakh support by ending the reprisal raids and promising that the Kazakhs could keep the Bashkir women and children living among them (a long-standing point of contention between Nepliuev and Khan Nurali of the Junior Jüz).[12] Thousands of Bashkirs would be massacred or taken captive by Kazakhs over the course of the uprising, whether in an effort to demonstrate loyalty to the Tsarist state, or as a purely opportunistic maneuver.[13][14]

In the period between 1764 and 1803, according to data collected by the Orenburg Commission, twenty Russian caravans were attacked and plundered. Kazakh raiders attacked even big caravans which were accompanied by numerous guards.[15]

In spring 1774, the Russians demanded the Khan return 256 Russians captured by a recent Kazakh raid.[16]

In summer 1774, when Russian troops in the Kazan region were suppressing the rebellion led by the Cossack leader Pugachev, the Kazakhs launched more than 240 raids and captured many Russians and herds along the border of Orenburg.[16]

Darrel P. Kaiser wrote, "Kazakh-Kirghiz tribesmen kidnapped 1573 German settlers in Russia. In 1774 alone and only half were successfully ransomed. The rest were killed or enslaved."[17]

Caesarfeld, founded in 1774, was attacked by Kazakh or Kirghiz tribesmen and destroyed. The Catholic village of Chaisol was destroyed in 1774. The second attack on the Karaman in the colony of Mariental took place in August 1774. All the livestock and the people and property were stolen and carried across the Ural River into the Russian steppe. The total number of captives taken away from Mariental was about 300, of whom very few came back. Those captives that survived (mostly women and children) were eventually sold by the Kirghiz into the harems of wealthy Muslims in areas under the control of Turkey.[18]

In October 24, 1774, the Kazakh or Kirghiz attacked the colonies of Seelmann, Leitsinger, Keller, and Holzel, and carried away 317 persons into slavery.[18]

In 1776, the colony of the Mariental was attacked and its inhabitants were enslaved. One story tells that someone (probably Pastor Werboner) had his tongue cut out and that hundreds of people were beheaded.[18]

In August 16, 1785 was the last attack on the colonies by the Kazakh-Kyrgyz; a woman, a child and four elders were killed and 130 people taken as prisoners during the attack. Government forces quickly caught the attackers while the latter were moving the prisoners. In the battle, 70 Kazakhs and Kyrgyz were killed and all the prisoners were freed.[18]

In 1799, the biggest Russian caravan which was plundered at that time lost goods worth 295,000 rubles.[18]

By 1830, the Russian government estimated that two hundred Russians were kidnapped and sold into slavery in Khiva every year.[19]

Russian empire slave trade on Kazakh settlement

In 1737, Empress of Russia Anna Ioannovna issued an order that legalized slave trade in Siberia.[20]

According to some artifacts, price of a Kazakh male was ten rubles, and Kazakh female was six rubles.[20]

There were many accounts of Russian Cossack raids that captured Kazakh families, which were then taken to Petropavlovsk and Omsk, where they were sold to wealthy Russian land owners into serfdom.[20]

By the end of 18th century, the lands of Kazakh Junior Jüz (or Junior Horde) were incorporated into the Russian Empire, and raids by Kazakhs on Russian colonies has gradually declined and stopped.[18]

On May 23, 1808, Governor Peter Kaptzevich signed an order that freed all slave or serf Kazakhs of both genders who reached the age of 25.[20]

Abolition of slavery

The Russian administration liberated the slaves of the Kazakhs in 1859.[21] However, isolated abductions of Russians or Ukrainians by Kazakhs for the slave markets of Central Asia continued until the Tsars' conquest of Khiva and Bukhara in the 1860s.[22] At major markets in Bukhara, Samarkand, Karakul, Karshi and Charju, slaves consisted mainly of Iranians and Russians, and some Kalmuks; they were brought there by Turkmen, Kazakh and Kyrgyz.[23] A notorious slave market for captured Russian and Persian slaves was centered in the Khanate of Khiva from the 17th to the 19th century.[24] During the first half of the 19th century alone, some one million Persians, as well as an unknown number of Russians, were enslaved and transported to Central Asian khanates.[25][26] When Russian troops took Khiva in 1873 there were 29,300 Persian slaves, captured by Turkoman raiders. According to Josef Wolff (Report of 1843–1845) the population of the Khanate of Bukhara was 1,200,000, of whom 200,000 were Persian slaves.[27]

See also

- List of Turkic dynasties and countries

- History of Kazakhstan

- List of Kazakh khans

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

- Nomad (2006 film)

- Kazakh Khanate: the Diamond Sword (film 2017)

- Kazakh Khanate: the Golden Throne (film 2019)

References

- "Kazakh Khanate – 550th anniversary". e-history.kz.

- "Kazakhstan to Celebrate 550th Kazakh Statehood Anniversary in 2015". Astana Times.

- "Haqq Nazar | Kazakh ruler". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2016-02-02.

- A History of the Moghuls of Central Asia: The Tarikh-i-Rashidi

- A History of the Moghuls of Central Asi: The Tarikh-i-Rashidi By Mirza Muhammad Haidar Dughlt, N. Elias, Sir E Denison Ross page 121

- A History of the Moghuls of Central Asi: The Tarikh-i-Rashidi - Mirza Muhammad Haidar Dughlt - Google Books. Books.google.com.pk. Retrieved 2016-02-02.

- Perdue, Peter C (2009). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia. Harvard University Press. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-674-04202-5.

- The History of the Central Asian Republics By Peter Roudik

- Eastern Destiny: Russia in Asia and the North Pacific by G. Patrick March

- Russia's Steppe Frontier: The Making Of A Colonial Empire 1500-1800 by Michael Khodarkovsky

- Formation of a Borderland Culture: Myths and Realities of Cossack-Kazakh By Yuriy Anatolyevich Malikov

- The Kazakhs by Martha Brill Olcott

- Russia's Steppe Frontier: The Making Of A Colonial Empire, 1500-1800 By Michael Khodarkovsky, pp. 167–168

- M. K. Palat, "Tsarist Russian Imperialism," Studies in History v. 4 (1988)

- Formation of a Borderland Culture: Myths and Realities of Cossack-Kazakh

- Russia's Steppe Frontier: The Making Of A Colonial Empire, 1500-1800 By Michael Khodarkovsky

- Darrel P. Kaiser (2006). Origin & Ancestors Families Karle & Kaiser Of the German-Russian Volga Colonies. Darrel P. Kaiser. ISBN 978-1-4116-9894-9. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- Origin & Ancestors Families Karle & Kaiser of the German-Russian Volga Colonies By Darrel P. Kaiser

- Pilgrims on the Silk Road: A Muslim-Christian Encounter in Khiva By Walter R. Ratliff

- История Казахстана | Работорговля Казахами в Сибири History Of Kazakhstan | Slave Trade in Siberia

- "Traditional Institutions in Modern Kazakhstan". Src-h.slav.hokudai.ac.jp. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- Commissar and Mullah: Soviet-Muslim Policy from 1917 To 1924 By Glenn L Roberts

- Vol. VI: Towards Contemporary Civilization: From the Mid-Nineteenth Century ... edited by Chahryar Adle, Madhavan K.. Palat, Anara Tabyshalieva

- "Adventure in the East – TIME". Time. 6 April 1959. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- Ichan-Kala, Encyclopædia Britannica

- Mayhew, Bradley. "Fabled Cities of Central Asia: Samarkand, Bukhara, Khiva: Robin Magowan, Vadim E. Gippenreiter". Amazon.com. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- Report of Josef Wolff 1843–1845