Herero people

The Herero, also known as Ovaherero, are Bantu ethnic group inhabiting parts of Southern Africa. The majority reside in Namibia, with the remainder found in Botswana and Angola. There were an estimated 250,000 Herero people in Namibia in 2013. They speak Otjiherero, a Bantu language. In Botswana, the Hereros or Ovahererero are mostly found in Maun and some villages surrounding Maun.These villages among others are Sepopa,Toromuja,Karee and Etsha.Some of them are at Mahalapye.In the South eastern part of Botswana they are at Pilane.There are also a few of them in the Kgalagadi South,that is Tsabong,Omawaneni,Draaihoek and Makopong Villages.Ovaherero are known as bold culture keepers.The big ball gown dress and the head gear are the main wear for women while men are mostly seen with leather hats and walking sticks. Ovaherero are good in food preservation.Some if the food they preserve is milk and meat. They make sour milk and dry meat to use for a longer time .

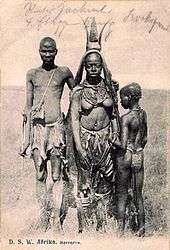

Herero women in traditional attire | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 250,000 (Namibia only) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Herero (Otjiherero) | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional faith, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ovimbundu, Ovambo and Other Kavango-Southwest Bantu peoples |

| Herero | |

|---|---|

| Person | Omuherero |

| People | Ovaherero |

| Language | Otjiherero |

Overview

Unlike most Bantu, who are primarily subsistence farmers,[1] the Herero are traditionally pastoralists. They make a living tending livestock.[2] Cattle terminology in use among many Bantu pastoralist groups testifies that Bantu herders originally acquired cattle from Cushitic pastoralists inhabiting Eastern Africa. After the Bantu settled in Eastern Africa, some Bantu nations spread south. Linguistic evidence also suggests that the Bantu borrowed the custom of milking cattle from Cushitic peoples; either through direct contact with them or indirectly via Khoisan intermediaries who had acquired both domesticated animals and pastoral techniques from Cushitic migrants.[3][4]

Organization

The Herero claim to comprise several sub-divisions, including the Himba, Tjimba (Cimba), Mbanderu, and Kwandu. Groups in Angola include the Mucubal Kuvale, Zemba, Hakawona, Tjavikwa, Tjimba and Himba, who regularly cross the Namibia/Angola border when migrating with their herds. However, the Tjimba, though they speak Herero, are physically distinct indigenous hunter-gatherers. It may be in the Hereros' interest to portray indigenous peoples as impoverished Herero who do not own livestock.[5]

The leadership of the Ovaherero is distributed over eight royal houses, among them:[6][7]

- Ovaherero Traditional Authority, of the Ovaherero Kingdom, Paramount Chief Vekuii Rukoro

- Maharero Royal Traditional Authority, chief Tjinaani Maharero

- Zeraeua Royal Traditional Authority at Otjimbingwe

- Ovambanderu Royal Traditional Authority, chief Kilus Karaerua Nguvauva

- Onguatjindu Royal Traditional Authority at Okakarara, chief Sam Kambazembi

Since conflicts with the Nama people in the 1860s necessitated Ovaherero unity, they also have a paramount chief ruling over all eight royal houses,[7] although there is currently an interpretation that such paramount chieftaincy violates the Traditional Authorities Act, Act 25 of 2000.[6]

History

Pre-colonial

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the Herero migrated to what is today Namibia from the east and established themselves as herdsmen. In the beginning of the 19th century, the Nama from South Africa, who already possessed some firearms, entered the land and were followed, in turn, by white merchants and German missionaries. At first, the Nama began displacing the Herero, leading to bitter warfare between the two groups, which lasted the greater part of the 19th century. Later the two peoples entered into a period of cultural exchange.

German South West Africa

During the late 19th century, the first Europeans began entering to permanently settle the land. Primarily in Damaraland, German settlers acquired land from the Herero in order to establish farms. In 1883, the merchant Franz Adolf Eduard Lüderitz entered into a contract with the native elders. The exchange later became the basis of German colonial rule. The territory became a German colony under the name of German South West Africa.

Soon after, conflicts between the German colonists and the Herero herdsmen began. Controversies frequently arose because of disputes about access to land and water, but also the legal discrimination against the native population by the white immigrants.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, imperialism and colonialism in Africa peaked, affecting especially the Hereros and the Namas. European powers were seeking trade routes and railways, as well as more colonies. Germany officially claimed their stake in a South African colony in 1884, calling it German South West Africa until it was taken over in 1915. The first German colonists arrived in 1892, and conflict with the indigenous Herero and Nama people began. As in many cases of colonization, the indigenous people were not treated fairly.[8]:31 [9]

Between 1893 and 1903, the Herero and Nama people's land and cattle were progressively being taken by German colonists. The Herero and Nama resisted expropriation[10] over the years, but they were unorganized and the Germans defeated them with ease. In 1903, the Herero people learned that they were to be placed in reservations,[11] leaving more room for colonists to own land and prosper. In 1904, the Herero and Nama began a great rebellion that lasted until 1907, ending with the near destruction of the Herero people. "The war against the Herero and Nama was the first in which German imperialism resorted to methods of genocide...."[12] Roughly 80,000 Herero lived in German South West Africa at the beginning of Germany's colonial rule over the area, while after their revolt was defeated, they numbered approximately 15,000. In a period of four years, approximately 65,000 Herero people perished.[13]

Samuel Maharero, the Supreme Chief of the Herero, led his people in a large-scale uprising on January 12, 1904, against the Germans.[14] The Herero, surprising the Germans with their uprising, had initial success.

German General Lothar von Trotha took over as leader in May 1904.[15] In August 1904, he devised a plan to annihilate the Herero nation.[16] The plan was to surround the area where the Herero were, leaving but one route for them to escape, into the desert. The Herero battled the Germans, and the losses were minor. It was when the majority had escaped through the only passage made available by the Germans, and had been systematically prevented from approaching watering holes, that starvation began to take its toll. It was then that the Herero uprising changed from war, to genocide.[17] Lothar von Trotha called the conflict a “race war.” He declared in the German press that “no war may be conducted humanely against non-humans” and issued an “annihilation order”: ...The Herero are no longer German subjects. They have murdered and stolen, they have cut off the ears, noses and other body parts of wounded soldiers, now out of captain will receive 1000 Mark, whoever delivers Samuel will receive 5000 Mark. The Herero people must however leave the land. If the populace does not do this I will force them with the Groot Rohr [cannon]. Within the German borders every Herero, with or without a gun, with or without cattle, will be shot. I will no longer accept women and children, I will drive them back to their people or I will let them be shot at. [18] [19]

On the 100th anniversary of the massacre, German Minister for Economic Development and Cooperation Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul commemorated the dead on site and apologized for the crimes on behalf of all Germans. Hereros and Namas demanded financial reparations, however in 2004 there was only minor media attention in Germany on this matter.[20]

Culture

.jpg)

The Herero are traditionally cattle-herding pastoralists who rate status on the number of cattle owned. Cattle raids occurred between Herero groups, but Herero land (Ehi Rovaherero) belongs to the community and has no fixed boundaries.

The Herero have a bilateral descent system. A person traces their heritage through both their father's lineage, or oruzo (plural: otuzo), and their mother's lineage, or eanda (plural: omaanda).[21] In the 1920s, Kurt Falk recorded in the Archiv für Menschenkunde that the Ovahimba retained a "medicine-man" or "wizard" status for homosexual men. He wrote, "When I asked him if he was married, he winked at me slyly and the other natives laughed heartily and declared to me subsequently that he does not love women, but only men. He nonetheless enjoyed no low status in his tribe."[22] The Holy Fire okuruuo (OtjikaTjamuaha) of the Herero is located at Okahandja. During immigration the fire was doused and quickly relit. From 1923 to 2011, it was situated at the Red Flag Commando. On Herero Day 2011, a group around Paramount Chief Kuaima Riruako claimed that this fire was facing eastwards for the past 88 years, while it should be facing towards the sunset. They removed it and placed it at an undisclosed location, a move that has stirred controversy among the ovaherero community.[23]

Dress

Despite sharing a language and pastoral traditions, the Herero are not a homogeneous people. Traditional leather garments are worn by northwestern groups, such as the Himba, Kuvale, and Tjimba, who also conserve pre-colonial traditions in other aspects: for example, they do not buy bedding, but rather sleep in bedding made of cow skin. The Kaokoland Herero and those in Angola have remained isolated and are still pastoral nomads, practising limited horticulture.[24]

However, the main Herero group in central Namibia (sometimes called Herero proper) was heavily influenced by Western culture during the colonial period, creating a whole new identity. The dress of the Herero proper, and their southern counterparts the Mbanderu, incorporates and appropriates the styles of clothing worn by their German colonisers. Though the attire was initially forced upon the Herero, it now operates as a new tradition and a point of pride.

During the 1904-07 war, Herero warriors would steal and wear the uniforms of German soldiers they had killed, believing that this transferred the dead soldiers' power to them. Today, on ceremonial occasions, Herero men wear military-style garb, including peaked caps, berets, epaulettes, aiguilettes and gaiters, "to honour the fallen ancestors and to keep the memories alive."[25]

Herero women adopted the floor-length gowns worn by German missionaries in the late 19th century, but now make them in vivid colours and prints. Married and older Herero women wear the dresses, locally known as ohorokova, every day, while younger and unmarried women wear them mainly for special occasions.[26] Ohorokova dresses are high-necked and have voluminous skirts lavishly gathered from a high waist or below the bust, incorporating multiple petticoats and up to ten metres of fabric. The long sleeves display sculptural volume: puffed from the shoulders or frilled at the wrists. Coordinating neckerchiefs are knotted around the neck. For everyday wear, dresses are ingeniously patchworked together from smaller pieces of fabric, which may be salvaged from older garments. Dresses made from a single material are reserved for special occasions.

The most distinctive feature of Herero women's dress is their horizontal horned headdress, the otjikaiva, which is a symbol of respect, worn to pay homage to the cows that have historically sustained the Herero. The headdresses can be formed from rolled-up newspaper covered in fabric. They are made to match or coordinate with dresses, and decorative brooches and pins attached to the centre front. The overall intended effect is for the woman to resemble a plump, slow-moving cow. In photographs, Herero women adopt the 'cow pose', with their arms raised, palms upwards.

This dress style continues to evolve. In urban Windhoek, fashion designers and models are updating Herero dress for modern, younger wearers, including glamorous sheer and embellished fabrics. "Change is difficult, I understand, but people need to get used to the change," says designer McBright Kavari. "I'm happy to be a part of the change, to be winning souls of people and making people happy when they are wearing the Herero dress."[27] Kavari has won the Best Herero Dress competition three times in a row, but has been criticised for raising the hem of the garment to the knee.[28]

Language

The Herero language (Otjiherero) is the main unifying link among the Herero peoples. It is a Bantu language, part of the Niger–Congo family.[29] Within the Otjiherero umbrella, there are many dialects, including Oluthimba or Otjizemba—which is the most common dialect in Angola—Otjihimba, and Otjikuvale. These differ mainly in phonology, and are largely mutually intelligible, though Kuvale, Zemba, and Hakaona have been classified as separate languages. Standard Herero is used in the Namibian media and is taught in schools throughout the country.

Religion

Herero people believe in Okuruo (holy fire), which is a link to their ancestors to speak to God and Jesus Christ on their behalf. Modern-day Herero are mostly Christians, primarily Catholic, Lutheran, and Born-again Christian.

Omuroi

Omuroi is a Herero noun for someone suspected witchcraft, flies at night, or rides people at night. More like phantom or ghost person, some claim to struggle with sleeping when a certain person is around due to their belief of that person possessing omuroi. Others claim to also believe that such beings talk at night and when such voices are heard, a shout may scare them away.

Others resort to sleeping with candles on, believing that the omuroi are averse to light. Some may even bring in spiritual doctors to perform ceremonies to chase this omuroi away. This superstition has been passed on for generations and is still current in modern Herero culture.

Domestic animals

The Herero making a living out of rearing domestic animals.

Cattle

Cattle are most valued domestic animals in the Herero culture, therefore cattle herding is the most significant and substantial activity for the Herero people. In the Herero culture the cattle herding and cattle trading activities are only conducted by males while females are responsible for milking cows, household chores, harvesting small field crops and taking care of the young children. As women are responsible for milking cows, there are also responsible for preparing the delicious sour milk called "Omaere".[30] Although males are responsible for the cattle trading activities the females do most of the trading such as bartering for other goods.

Cultural impact

The Herero people take pride in their cattle, hence the culture of Herero requires women to wear their iconic fabric hats shaped like cow horns.[30] They believe that the more cattle one has, the richer one is, making cattle a symbol of wealth. In celebrations such as marriages, cattle is normally eaten, whereas religious or ancestral veneration ceremonies involve the sacrifice of cows or other animals.

Goats and sheep

Goats and sheep are kept for their meat and milk. Goatskin is manufactured into child carriers and to create household ornaments. Goat dung, meanwhile, is considered medicinal;[31] it is normally used to treat chickenpox.

Horses and donkeys

Horse and donkeys are common means of transport for the Herero. In cases of herding or searching for lost domestic animals, the Herero engage horses to carry out these activities.

Herero people also consume donkey meat, but rarely consume horse meat.

Herero in fiction

- A group of Herero living in Germany who were inducted into the German military during the Second World War play a major part in Thomas Pynchon's novel Gravity's Rainbow. The genocide under von Trotha plays a major role in another novel by the same author, V..

- German author Uwe Timm's novel Morenga, set in German South West Africa, includes several Herero characters.

- A Portuguese-Herero mestiça protagonist is featured in Guy Saville's novel The Afrika Reich. The fictional story takes place in a 1952 Africa largely conquered by the Nazis who came away from World War II politically and economically empowered and relatively unopposed.

- In the historical novel Mama Namibia by Mari Serebrov, two perspectives of the 1904 genocide in German Southwest Africa are shown. The first is that of Jahohora, a 12-year-old Herero girl who survives alone in the veld for two years after her family is killed by German soldiers. The second is that of Kov, a Jewish doctor who volunteered to serve in the German military to prove his patriotism. As he witnesses the atrocities of the genocide, he rethinks his loyalty to the Fatherland.[32]

- The Treatment of the Herero by German colonists is the subject of the 2012 play We Are Proud To Present A Presentation About The Herero Of Namibia, Formerly Known As South West Africa, From The German Sudwestafrika, Between The Years 1884–1915 by Jackie Sibblies Drury.

See also

References

- Immaculate N. Kizza, The Oral Tradition of the Baganda of Uganda: A Study and Anthology of Legends, Myths, Epigrams and Folktales, , p. 21: "The Bantu were, and still are, primarily subsistence farmers who would settle in areas, clear land, organize themselves in larger units basically for protective purposes, and start permanent settlements."

- Mark Cocker, Rivers of Blood, Rivers of Gold: Europe's Conquest of Indigenous Peoples, Grove Press, 2001, p. 276

- J. D. Fage, A History of Africa, Routledge, 2002, p. 29: "In the north-east, the Bantu entered 'Azanian' lands inhabited by peoples speaking southern Cushitic languages. Indeed, this was of some importance because there is firm archaeological evidence that modern Kenya and northern Tanzania were the home of a succession of societies, once known as the 'Stone Bowl' cultures, which from about the middle of the third millennium B.C. onwards had cattle and were developing food-producing techniques well suited to the environment. It is unlikely that the Bantu would have brought large cattle with them through the forest, and their cattle terminology suggests that they acquired cattle from eastern African speakers of Cushitic languages, possibly through the mediation of Khoisan-speaking peoples. There is also linguistic evidence to suggest that at a later stage the Bantu may have borrowed the practice of milking directly from Cushitic-speaking peoples in East Africa."

- Blench, Roger (8 August 2008). "Was there an interchange between Cushitic pastoralists and Khoisan speakers in the prehistory of Southern Africa and how can this be detected?" (PDF). Presented at Königswinter, March 28-30, 2007 and to be published in a special volume of Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

pastoralists speaking Cushitic languages once spread as far as south-central Africa, where they were in contact with the ancestors of present-day Khoe-speakers. This led to a transfer of both species of domestic animals and also some rather specific techniques of pastoral lifestyle including dairy-processing etc. Khoe pastoral culture is known mainly from records and their original sheep and cattle breeds have now become heavily crossbred. The explanation for related traits among adjacent Bantu peoples is likely to be a similar, subsequent transfer from the Khoe to the Bantu, although it is possible that there was also direct Cushitic contact with the Bantu in the same region.

- Roger Blench, Are the African Pygmies an Ethnographic Fiction?

- Immanuel, Shinovene (24 October 2014). "Rukoro chieftaincy rejected". The Namibian. p. 1.

- Kandetu, Bob (23 October 2014). "Kambazembi and Rukoro Await their Reigns". Informanté.

- Jan-Bart Gewald (1998) Herero heroes: a socio-political history of the Herero of Namibia, 1890-1923, James Currey, Oxford ISBN 978-0-82141-256-5

- Peace and freedom, Volume 40, Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, page 57, The Section, 1980

- "A bloody history: Namibia’s colonisation", BBC News, 29 August 2001

- Samuel Totten, Paul Robert Bartrop, Steven L. Jacobs (2007) Dictionary of Genocide: A-L, p.184, Greenwood Press, Westport, Conn. ISBN 978-0-31334-642-2

- Chalk, Frank, and Jonassohn, Kurt. The History and Sociology of Genocide: Analyses and Case Studies. Published in cooperation with the Montreal Institute for Genocide Studies. (Yale University Press: New Haven & London, 1990)

- UN Whitaker Report on Genocide, 1985, paragraphs 14 to 24, pages 5 to 10 Prevent Genocide International

- The New York Times. 18 August 1904

- The Times (London). 7 May 1904

- Mahmood Mamdani (2001) When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, Princeton University Press, Princeton ISBN 978-0-69105-821-4

- "Germany moves to atone for 'forgotten genocide' in Namibia". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- "German science and black racism—roots of the Nazi Holocaust". The FASEB Journal. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- Haas, François. "General Lothar Von Trotha Extermination Order against the Herero". encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- Krabbe, Alexander. "Remembering Germany's African Genocide". OhmyNews International. Archived from the original on 2004-09-05. Retrieved 2004-08-06.

- 1 How Societies Are Born by Jan Vansina: "Of Water, Cattle, and Kings"

- Boy-Wives and Female Husbands edited by Stephen Murray & Will Roscoe. Published by Saint Martin's Press in 1998. p. 190

- Nunuhe, Margreth (31 August 2011). "Holy fire relocation triggers storm". New Era. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012.

- Carvalho, Ruy Duarte (2000). Vou lá visitar pastores. Rio Mouro, Portugal: Círculo de Leitores, Printer Portuguesa Casais de Mem Martins. ISBN 972-42-2092-3.

- Stinson, Liz (24 June 2013). "Photos: The Amazing Costume Culture of Africa's Herero Tribe". Wired. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- Young, Lisa (July 2004). "Herero Dresses – The Bigger The Better". Travel News Namibia. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- "Namibia: The Trauma & Triumph Of Herero Dresses". Refinery29. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- Kaakunga, Rukee (7 December 2012). "The Iconic Herero Dress Deconstructed". The Namibian. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- Herero language at Ethnologue (16th ed., 2009)

- "Herero People: Hats & History". University of San Francisco. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14.

- "Domestic Animal Farming in the Fransfontein Area".

- Serebrov, Mari. Mama Namibia. Windhoek, Namibia: Wordweaver Publishing House, 2013.

Further reading

- Rachel Anderson, "Redressing Colonial Genocide Under International Law: The Hereros' Cause of Action Against Germany", 93 California Law Review 1155 (2005).

- S. Passarge, Südafrika, (Oldenburg and Leipzig, 1908)

- Hans Schinz, Deutsch Südwest-Afrika, (Oldenburg and Leipzig, 1891)

- Herero people

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Herero. |

- Africa on the Matrix: Herero People of Namibia—Photographs and information.