Ket people

Kets (Russian: Кеты; Ket: Ostygan) are a Yeniseian people in Siberia. In the Russian Empire, they were called Ostyaks, without differentiating them from several other Siberian peoples. Later they became known as Yenisey ostyaks, because they lived in the middle and lower basin of the Yenisei River in the Krasnoyarsk Krai district of Russia.[3] The modern Kets lived along the eastern middle stretch of the river before being assimilated politically into Russia between the 17th and 19th centuries. According to the 2010 census, there were 1,220 Kets in Russia.[1]

Kets | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ca. 1,600 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Krasnoyarsk Krai (Russia) | |

| 1,219 (2010)[1] | |

| 37 (2001)[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Ket, Russian | |

| Religion | |

| Russian Orthodoxy, Animism, Shamanism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Yugh people | |

Shown within Russia | |

| Location | Most Ket live on the middle Yenisei River and tributaries, including a group in the community of Kellog. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 62°29′N 86°16′E |

History

The Ket are thought to be the only survivors of an ancient nomadic people believed to have originally lived throughout central and southern Siberia. In the 1960s the Yugh people were distinguished as a separate, though similar, group. Today's Kets are the descendants of the tribes of fishermen and hunters of the Yenisei taiga, who adopted some of the cultural ways of those original Ket-speaking tribes of South Siberia. The earlier tribes engaged in hunting, fishing, and even reindeer breeding in the northern areas.[1]

The Ket were incorporated into the Russian state in the 17th century. Their efforts to resist were futile as the Russians deported them to different places to break up their resistance. This also broke up their strictly organized patriarchal social system and their way of life disintegrated. The Ket people ran up huge debts with the Russians. Some died of famine, others of diseases introduced from Europe. By the 19th century, the Kets could no longer survive without food support from the Russian state.[4]

In the 20th century, the Soviets forced collectivization upon the Ket. They were officially recognized as Kets in the 1930s when the Soviet Union started to implement the self-definition policy with respect to indigenous peoples. However, Ket traditions continued to be suppressed and self-initiative was discouraged. Collectivization was completed by the 1950s and the Russian lifestyle and language forced upon the Ket people.

The population of Kets has been relatively stable since 1923. According to the 2002 census, there were 1,494 Kets in Russia. This compares with 1,200 in the 1970 census. Today the Ket live in small villages along riversides and are no longer nomadic.

Language

The Ket language has been linked to the Na-Dené languages of North America in the Dené–Yeniseian language family.[5][6][7] This link has led to some collaboration between the Ket and some northern Athabaskan peoples.[8]

Ket means "man" (plural deng "men, people"). The Kets of the Kas, Sym and Dubches rivers use jugun as a self-designation. In 1788 Peter Simon Pallas was the earliest scholar to publish observations about the Ket language in a travel diary.

In 1926, there were 1,428 Kets, of whom 1,225 (85.8%) were native speakers of the Ket language. The 1989 census counted 1,113 ethnic Kets with only 537 (48.3%) native speakers left.

As of 2008, there were only about 100 people who still spoke Ket fluently, half of them over 50.[5] It is entirely different from any other language in Siberia.[1] Alexander Kotusov (1955–2019) was a Ket folk singer, composer and writer of songs in the Ket language.[9]

Culture

The Ket traditional culture was researched by Matthias Castrén, Vasiliy Ivanovich Anuchin, Kai Donner, Hans Findeisen, and Yevgeniya Alekseyevna Alekseyenko.[10] Shamanism was a living practice into the 1930s, but by the 1960s almost no authentic shamans could be found. Shamanism is not a homogeneous phenomenon, nor is shamanism in Siberia. As for shamanism among Kets, it shared characteristics with those of Turkic and Mongolic peoples.[11] Additionally, there were several types of Ket shamans,[12][13] differing in function (sacral rites, curing), power, and associated animals (deer, bear).[13] Also, among Kets (as with several other Siberian peoples such as the Karagas[14][15][16]) there are examples of the use of skeleton symbolics.[11] Hoppál interprets this as a symbol of shamanic rebirth,[17] although it may symbolize also the bones of the loon (the helper animal of the shaman, joining the air and underwater worlds, just like the story of the shaman who travelled both to the sky and the underworld).[18] The skeleton-like overlay represented shamanic rebirth among some other Siberian cultures as well.[19]

Of great importance to Kets are dolls, described as "an animal shoulder bone wrapped in a scrap of cloth simulating clothing."[20] One adult Ket, who had been careless with a cigarette, said, "It's a shame I don't have my doll. My house burnt down together with my dolls."[21] Kets regard their dolls as household deities, which sleep in the daytime and protect them at night.[22]

Vajda spent a year in Siberia studying the Ket people, and finds a relationship between the Ket language and the Na-Dene languages, of which Navajo is the most prominent and widely spoken.

Vyacheslav Ivanov and Vladimir Toporov compared Ket mythology with that of Uralic peoples, assuming in the studies that they are modelling semiotic systems in the compared mythologies. They have also made typological comparisons.[23][24] Among other comparisons, possibly from Uralic mythological analogies, the mythologies of Ob-Ugric peoples[25] and Samoyedic peoples[26] are mentioned. Other authors have discussed analogies (similar folklore motifs, purely typological considerations, and certain binary pairs in symbolics) may be related to a dualistic organization of society—some dualistic features can be found in comparisons with these peoples.[27] However, for Kets, neither dualistic organization of society[28] nor cosmological dualism[29] have been researched thoroughly. If such features existed at all, they have either weakened or remained largely undiscovered.[28] There are some reports of a division into two exogamous patrilinear moieties,[30] folklore on conflicts of mythological figures, and cooperation of two beings in the creation of the land,[29] the motif of the earth-diver.[31] This motif is present in several cultures in different variants. In one example, the creator of the world is helped by a waterfowl as the bird dives under the water and fetches earth so that the creator can make land out of it. In some cultures, the creator and the earth-fetching being (sometimes called a devil, or taking the shape of a loon) compete with one another; in other cultures (including the Ket variant), they do not compete at all, but rather collaborate.[32]

However, if dualistic cosmologies are defined in a broad sense, and not restricted to certain concrete motifs, then their existence is more widespread; they exist not only among some Uralic peoples, but in examples on every inhabited continent.[33][34]

Origin

The Ket people share their origin with other Yeniseian people. They are closely related to other Siberians, East Asians and Indigenous peoples of the Americas. They are a Mongoloid population and belong mostly exclusive to yDNA haplogroup Q-M242.[35]

According to a recent study, the Ket and other Yeniseian people originated likely somewhere near the Altai Mountains or near Lake Baikal. Many Yeniseians got assimilated into today Turkic people. It is suggested that the Altaians are predominantly of Yeniseian origin and closely related to the Ket people. Other Siberian Turkic groups have also greatly assimilated Yeniseian people. The Ket people are also closely related to several Native American groups. According to this study, the Yeniseians are linked to Paleo-Eskimo groups.[36]

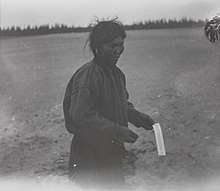

Ket woman, 1913

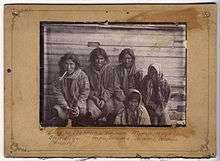

Ket woman, 1913 Ket women and children, 1913

Ket women and children, 1913 Kets, 1913

Kets, 1913 Kets, 1913

Kets, 1913 Ket people, 1913

Ket people, 1913 Ket people, 1913

Ket people, 1913 Kets, 1913

Kets, 1913 Ket people, 1913

Ket people, 1913 Ket people, 1913

Ket people, 1913 Houseboats of the Ket, 1914

Houseboats of the Ket, 1914 1914 photograph by the Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen of a group of Ket around a campfire. The people in the background wearing fur hats are Russians.

1914 photograph by the Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen of a group of Ket around a campfire. The people in the background wearing fur hats are Russians. Ket dolls

Ket dolls

Notes

- Vajda, Edward G. "The Ket and Other Yeniseian Peoples". Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2007.

- Ukrcensus.gov.ua

- "Ket: Bibliographical guide". Institute of Linguistics (Russian Academy of Sciences) & Kazuto Matsumura (Univ. of Tokyo). Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- "THE KETS". The Peoples of the Red Book. Retrieved 5 August 2006.

- "Ket language family linked to Na-Dene language family | orbis quintus". 10 March 2008. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- "Public Lecture: The Siberian Origin of the Na-Dene Languages". University of Alaska Fairbanks. 12 February 2008. Archived from the original on 28 May 2009. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- "Dene-Yeniseic Symposium, February 2008". University of Alaska Fairbanks. 10 February 2008. Archived from the original on 26 May 2009. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- "The Arctic Athabaskan Council and the Ket People of Siberian Russia Renew Historic Contacts and Agree to Work Together | Talking Alaska". talkingalaska.blogspot.com. 21 April 2010. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- Siberian Lang – Alexander Maksimovich Kotusov

- Hoppál 2005: 170–171

- Hoppál 2005: 172

- Alekseyenko 1978

- Hoppál 2005: 171

- Diószegi 1960: 128, 188, 243

- Diószegi 1960: 130

- Hoppál 1994: 75

- Hoppál 1994: 65

- Hoppál 2005: 198

- Hoppál 2005: 199

- A. A. Malygna, Dolls of the Peoples of Siberia 1988, p. 132, cited in Edward J. Vajda, Yeniseian Peoples and Languages: A History of Yeniseian Studies with an annotated bibliography and a source guide, Curzon Press, 2001.

- Werner Herzog, Happy People: A Year in the Taiga (documentary film) 2010.

- Herzog

- Ivanov & Toporov 1973

- Ivanov 1984:390, in editorial afterword by Hoppál

- Ivanov 1984: 225, 227, 229

- Ivanov 1984: 229, 230

- Ivanov 1984: 229–231

- Zolotaryov 1980: 39

- Zolotaryov 1980: 48

- Zolotaryov 1980: 37

- Ivanov 1984: 229

- Paulson 1975 :295

- Zolotarjov 1980: 56

- ḎḤWTY. "The Inexplicable Origins of the Ket People of Siberia". Ancient Origins. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Karafet, TM; Osipova, LP; Gubina, MA; Posukh, OL; Zegura, SL; Hammer, MF (2002). "High Levels of Y-Chromosome Differentiation among Native Siberian Populations and the Genetic Signature of a Boreal Hunter-Gatherer Way of Life". Hum Biol. 74: 761–89. doi:10.1353/hub.2003.0006. PMID 12617488.

- Flegontov, Pavel; Changmai, Piya; Zidkova, Anastassiya; Logacheva, Maria D.; Altınışık, N. Ezgi; Flegontova, Olga; Gelfand, Mikhail S.; Gerasimov, Evgeny S.; Khrameeva, Ekaterina E. (11 February 2016). "Genomic study of the Ket: a Paleo-Eskimo-related ethnic group with significant ancient North Eurasian ancestry". Scientific Reports. 6: 20768. doi:10.1038/srep20768. PMC 4750364. PMID 26865217.

References

- Alekseyenko, E. A. (1978). "Categories of Ket Shamans". In Diószegi, Vilmos; Hoppál, Mihály (eds.). Shamanism in Siberia. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

- Diószegi, Vilmos (1960). Sámánok nyomában Szibéria földjén. Egy néprajzi kutatóút története (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magvető Könyvkiadó. The book has been translated to English: Diószegi, Vilmos (1968). Tracing shamans in Siberia. The story of an ethnographical research expedition. Translated from Hungarian by Anita Rajkay Babó. Oosterhout: Anthropological Publications.

- Hoppál, Mihály (1994). Sámánok, lelkek és jelképek (in Hungarian). Budapest: Helikon Kiadó. ISBN 963-208-298-2. The title means "Shamans, souls and symbols".

- Hoppál, Mihály (2005). Sámánok Eurázsiában (in Hungarian). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-8295-3. The title means "Shamans in Eurasia", the book is written in Hungarian, but it is published also in German, Estonian and Finnish. Site of publisher with short description on the book (in Hungarian)

- Ivanov, Vyacheslav; Vladimir Toporov (1973). "Towards the Description of Ket Semiotic Systems". Semiotica. The Hague • Prague • New York: Mouton. IX (4): 318–346.

- Ivanov, Vjacseszlav (=Vyacheslav) (1984). "Nyelvek és mitológiák". Nyelv, mítosz, kultúra (in Hungarian). Collected, appendix, editorial afterword by Hoppál, Mihály. Budapest: Gondolat. ISBN 963-281-186-0. The title means: "Language, myth, culture", the editorial afterword means: "Languages and mythologies".

- Ivanov, Vjacseszlav (=Vyacheslav) (1984). "Obi-ugor és ket folklórkapcsolatok". Nyelv, mítosz, kultúra (in Hungarian). Collected, appendix, editorial afterword by Hoppál, Mihály. Budapest: Gondolat. pp. 215–233. ISBN 963-281-186-0. The title means: "Language, myth, culture", the chapter means: "Obi-Ugric and Ket folklore contacts".

- Middendorff, A. Th., von (1987). Reis Taimхrile. Tallinn.

- Paulson, Ivar (1975). "A világkép és a természet az észak-szibériai népek vallásában". In Gulya, János (ed.). A vízimadarak népe. Tanulmányok a finnugor rokon népek élete és műveltsége köréből (in Hungarian). Budapest: Európa Könyvkiadó. pp. 283–298. ISBN 963-07-0414-5. Chapter means: "The world view and the nature in the religion of the North-Siberian peoples"; title means: "The people of water fowls. Studies on lifes and cultures of the Finno-Ugric relative peoples".

- Zolotarjov, A.M. (1980). "Társadalomszervezet és dualisztikus teremtésmítoszok Szibériában". In Hoppál, Mihály (ed.). A Tejút fiai. Tanulmányok a finnugor népek hitvilágáról (in Hungarian). Budapest: Európa Könyvkiadó. pp. 29–58. ISBN 963-07-2187-2. Chapter means: "Social structure and dualistic creation myths in Siberia"; title means: "The sons of Milky Way. Studies on the belief systems of Finno-Ugric peoples".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ket people. |

- Professor Ed Vajda talking about the importance of the Ket and their language, plus a short story told by a Ket speaker.

- "The Kets". The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire.

- Edward J, Vajda. "The Ket and Other Yeniseian Peoples". Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 20 July 2005.

- Ethnologue on Ket

- Ket Language

- Endangered Languages of the Indigenous Peoples of Siberia – The Ket Language

- Yeniseian Peoples and Languages

- The Ket People – Center for Instructional Innovation and Assessment

- Starostin S.A.

- Multimedia Database of Ket, Documentation of Endangered Languages at Laboratory for Computer Lexicography Lomonosov Moscow State University.

- Ket texts, a Ket tale "Balna" in original + in Russian and English, with linguistic annotation.

- Pavel Flegontov; et al. (13 August 2015). "Genomic study of the Ket: a Paleo-Eskimo-related ethnic group with significant ancient North Eurasian ancestry". bioRxiv 10.1101/024554.