Koryaks

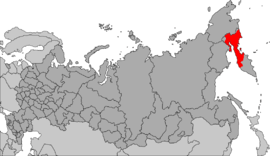

Koryaks (or Koriak, Russian: Коряки) are an indigenous people of the Russian Far East, who live immediately north of the Kamchatka Peninsula in Kamchatka Krai and inhabit the coastlands of the Bering Sea. The cultural borders of the Koryaks include Tigilsk in the south and the Anadyr basin in the north.

Koryak ceremony of starting the New Fire | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 8,022 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 7,953 (2010 census)[1] | |

| 69 (2001 census)[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Russian, Koryak | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Russian Orthodox Christianity also Shamanism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Chukotko-Kamchatkan peoples | |

The Koryaks are culturally similar to the Chukchis of extreme northeast Siberia. The Koryak language and Alutor (which is often regarded as a dialect of Koryak), are linguistically close to the Chukchi language. All of these languages are members of the Chukotko-Kamchatkan language family. They are more distantly related to the Itelmens on the Kamchatka Peninsula. All of these peoples and other, unrelated minorities in and around Kamchatka are known collectively as Kamchadals.

Neighbors of the Koryaks include the Evens to the west, the Alutor to the south (on the isthmus of Kamchatka Peninsula), the Kerek to the east, and the Chukchi to the northeast.

The Koryak are typically split into two groups: the coastal people Nemelan (or Nymylan) meaning 'village dwellers,' due to their living in villages. Their lifestyle is based on local fishing and marine mammal hunting. The inland Koryak, reindeer herders, are called Chaucu (or Chauchuven), meaning 'rich in reindeer.' They are more nomadic, following the herds as they graze with the seasons.[3]

According to the 2010 census, there were 7,953 Koryaks in Russia.

Etymology

The name Koryak was from the exonym word 'Korak,' meaning 'with the reindeer (kor)' in a nearby group Chukotko-Kamchatkan language.[4] The earliest references to the name 'Koryak' were recorded in the writings of the Russian cossack Vladimir Atlasov, who conquered Kamchatka for the Tsar in 1695.[5] The variant name was adopted by Russia in official state documents, hence popularizing it ever since.[4]

Origin

The origin of the Koryak is unknown. Anthropologists have speculated that a land bridge connected the Eurasian and North American continent during Late Pleistocene. It is possible that migratory peoples crossed the modern-day Koryak land en route to North America. Scientists have suggested that people traveled back and forth between this area and Haida Gwaii before the ice age receded. They theorize that the ancestors of the Koryak had returned to Siberian Asia from North America during this time.[3] Cultural and some linguistic similarity exist between the Nivkh and the Koryak.[6]

History

The Koryak once occupied a much larger area of the Russian Far East. Their overlapping borders extended to the Nivkh areas in Khabarovsk Krai until the Evens arrived, and pushed them into their present region.[6] A smallpox epidemic in 1769-1770 and warfare with Russian Cossacks reduced the Koryak population from 10-11,000 in 1700 to 4,800 in 1800.[7]

Under the Soviet Union, a Koryak Autonomous Okrug was formed in 1931 and named for this people. Based on the local referendum in 2005, this was merged with Kamchatka Krai effective 1 July 2007.[3]

Culture

Families usually gathered into groups of six or seven, forming bands. The nominal chief had no predominating authority, and the groups relied on consensus to make decisions, resembling common small group egalitarianism.

The lives of the people in the interior revolved around reindeer, their main source of food. They also used all the parts of its body to make sewing materials and clothing, tools and weapons. The meat was mostly eaten roasted and the blood, marrow and milk were drunk or eaten raw. The liver, heart, kidneys and tongue were considered delicacies. Salmon and other freshwater fish as well as berries and roots played a major part in the diet, as reindeer flesh did not contain some necessary vitamins and minerals, nor dietary fibre, needed to survive in the harsh tundra.

Today the Koryaks also buy processed food, such as bread, cereal and canned fish. They sell some reindeer each year for money, but can build up their herds due to the large population of reindeer.

.jpg)

Clothing was made out of reindeer hides, but nowadays men and women often have replaced that with cloth. The men wore baggy pants and a hide shirt, which often had a hood attached to it, boots and traditional caps made of reindeer skin. They still use the boots and caps. The women wore the same as the men, but with a longer shirt reaching to the calves. Today women often wear a head cloth and skirt, but wear the reindeer skin robe in cold weather.

The Koryak lived in domed shaped tents, called jajanga, or yaranga (from the more famous Chukchi term) similar to a tipi of the American Plains Indians, but less vertical, while some lived in yurts. The framework was covered in many reindeer skins. Few families still use the yaranga as dwellings, but some use them for trips to the tundra. The centre of the yaranga had a hearth, which has been replaced by an iron stove. Reindeer hide beds are placed to the east in the chum. They used small cupboards to store the families' food, clothing and personal items.

Transportation

.jpg)

The inland Koryak rode reindeer to get around, cutting off their antlers to prevent injuries. They also fitted a team of reindeer with harnesses and attached them to sleds to transport goods and people when moving camp.[8] Today the Koryak use snowmobiles more often than reindeer. Most inter-village transport is by air or boat, although tracked vehicles are used for travel to neighboring villages.[9]

They developed snowshoes, which they used in winter (and still do) when the snow is deep. Snowshoes are made by lashing reindeer sinew and hide strips to a tennis racket-shaped birch bark or willow hoop. The sinew straps are used to attach the shoe to the foot.

Children learned to ride a reindeer, sleigh, and use snowshoes at a very young age.

The other Koryak were skilled seafarers hunting whales and other marine mammals.

Religion

Koryaks believe in a Supreme Being whom they call by various names: Ñaíñinen (Universe/World), Ináhitela'n (Supervisor), Gichol-Eti'nvila'n (Master-of-the-Upper-World), Gi'chola'n (One-on-High), etc. He is considered to reside in Heaven with his family and when he wishes to punish mankind for immoral acts, he falls asleep and thus leaves man vulnerable to unsuccessful hunting and other ills.[10] Koryak mythology centers on the supernatural shaman Quikil (Big-Raven), who was created by the Supreme Being as the first man and protector of the Koryak.[3] Big Raven myths are also found in Southeast Alaska in the Tlingit culture, and among the Haida, Tsimshian, and other natives of the Pacific Northwest Coast Amerindians.[3]

Environment

Koryak lands are mountains and volcanic, covered in mostly Arctic tundra. Coniferous trees lie near the southern regions along the coast of the Shelekhova Bay of the Sea of Okhotsk. The northern regions inland are much colder, where only various shrubs grow, but these are enough to sustain reindeer migration.[3] The mean temperature in winter is –25 °C (-13 °F) while short summers are +12 °C (53 °F). The area they covered before Russian colonization was 301,500 km² (116,410 mi²), roughly corresponding to the Koryak Okrug, of which the administrative centre is Palana.[4] Today the Koryak are the largest minority group with 8,743 people. The krai's population is now majority ethnic Russian, descendants of the Cossack colonizers.

See also

- Haplogroup G (mtDNA)

- Alyutors (Koryak sub group)

- Anapel

- Apuka District

- Olyutorsky District

Footnotes

- Russian Census 2010: Population by ethnicity Archived 2012-04-24 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- State statistics committee of Ukraine - National composition of population, 2001 census] (Ukrainian)

- Chaussonnet, p28-29

- Kolga, pp.230-234

- Al'kor, Ia P., and A. K. Dranen. (1935) Kolonial'naia politika tsarizzna na Kamchatke, Leningrad: Tsentral'nyi istoricheskii arkhiv. Leningradskoe otdelenie.

- Friedrich and Diamond,

- "Indigenous Peoples of the Russian North, Siberia and Far East", Arctic Network for the Support of the Indigenous Peoples of the Russian Arctic

- Jochelson, Waldemar. 1908. The Koryak, Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History, vol. 10, parts 1–2: The Jesup North Pacific Expedition, Leiden: E. J. Brill

- King, Alexander D. (2011) Living with Koryak Traditions: Playing with Culture in Siberia, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Jochelson, Waldemar (1904). "The Mythology of the Koryak". American Anthropologist. 6 (4): 413–425. doi:10.1525/aa.1904.6.4.02a00010. JSTOR 659272.

References

- Chaussonnet, Valérie (1995) Crossroads Alaska: Native Cultures of Alaska and Siberia. Arctic Studies Center, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C. ISBN 9781560986614

- Friedrich and Diamond (1994) Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia - Eurasia / China. Volume 6. G.K. Hall and Company. Boston, Massachusetts. ISBN 0-8161-1810-8

- Kolga, Margus (2001) The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire. NGO Red Book. Tallinn, Estonia ISBN 9985-9369-2-2

- Gall, Timothy L. (1998) Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life: Koriaks. Detroit, Michigan: Gale Research Inc. ISBN 0-7876-0552-2

Further reading

- Kennan, George (1871). Tent Life in Siberia: And Adventures Among the Koraks and Other Tribes in Kamtchatka and Northern Asia. Putnam.; "Über die Koriaken u. ihnen nähe verwandten Tchouktchen," in But. Acad. Sc. St. Petersburg, xii. 99.

- Jochelson, Waldemar. The Koryak. New York: AMS Press, 1975. ISBN 0-404-58106-4

- Jochelson, Vladimir Il'ich, and F. Boas. Religion and Myths of the Koryak Material Culture and Social Organization of the Koryak. New York: [s.n.], 1908.

- Nagayama, Yukari ed. The Magic Rope Koryak Folktale. Kyoto, Japan: ELPR, 2003.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Koryaks. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Koriaks. |

- Koryaks.net: Website about the Koryak people

- Transgender shamans

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.