Nenets people

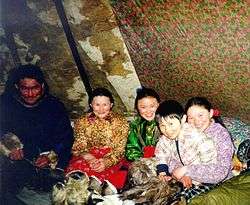

The Nenets (Nenets: ненэй ненэче, nenəj nenəče, Russian: ненцы, nentsy), also known as Samoyed, are a Samoyedic ethnic group native to northern arctic Russia, so called Russian Far North. According to the latest census in 2010, there were 44,857 Nenets in the Russian Federation, most of them living in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, Nenets Autonomous Okrug and Taymyrsky Dolgano-Nenetsky District stretching along the coastline of the Arctic Ocean near the so called Arctic Circle between Kola and Taymyr peninsulas. The Nenets people speak either the Tundra or Forest Nenets languages, which are mutually unintelligible.

_kvinner_og_barn_foran_inngangen_til_teltet_sitt._(6435260555).jpg) The Nenets, 1913 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 44,857 (2010 Census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Russia | |

| 44,640[1] | |

| 217[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Nenets, Russian, Komi | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly: Shamanism, Animism Minority: Eastern Orthodox Christianity (Russian Orthodox Church) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Enets, Nganasans, Selkups | |

In the Russian Federation they have a status of indigenous small-numbered peoples or "little people".[3]

Name

The literal morphs samo and yed in Russian convey the meaning "self-eater", which is considered derogatory. Therefore, the name Samoyed quickly went out of usage in the 20th century. The people are known as the Nenets, which means "man".

In old Russian documents the term Samoyed was often applied indiscriminately to different peoples of Northern Russia who speak related Uralic languages: Nenets, Nganasans, Enets, Selkups (speakers of Samoyedic languages). Currently, the term "Samoyedic peoples" applies to the whole group of these different peoples. It is the general term that includes the Nenets, Enets, Selkup, and Nganasan peoples.

Language

The Nenets language is on the Samoyedic branch of the Uralic language family, with two major dialects, Forest Nenets and Tundra Nenets.[4] Ethnologue says that in Siberia, most young people are still fluent in Nenets, whereas in European Russia, they tend to speak Russian. Overall, the majority of native speakers are from older generations. UNESCO classifies Nenets as an endangered language.[5] Some believe that the use of Russian and Komi is due to inter-ethnic marriages.[6]

History and way of life

.jpg)

.jpg)

There are two distinct groups of Nenets sensu stricto, based on their economy: the Tundra Nenets (living far to the north) and the Khandeyar or Forest Nenets. A distinct third group of Nenets (Yaran people) has emerged as a result of intermarriages between Nenets and Izhma Komi people.

The Samoyedic languages form a branch of the Uralic language family. They moved from farther south in Siberia to the northernmost part of what later became Russia sometime before the 12th century.

They ended up between the Kanin and Taymyr peninsulas, around the Ob and Yenisey rivers, with only a few of them settling into small communities like Kolva. Their main subsistence comes from hunting and reindeer herding. Using reindeer as a draft animal throughout the year enables them to cover great distances. Large-scale reindeer herding emerged in the 18th century. They bred the Samoyed dog to help herd their reindeer and pull their sleds, and European explorers later used these dogs for polar expeditions, because they were well adapted to the arctic conditions. Tundra wolves can cause considerable economic loss, as they prey on the reindeer herds which are the livelihood of some Nenets families.[7] Along with reindeer meat, fish is a major component in the Nenets' diet. Nenets housing is conical yurt (mya).

They have a shamanistic and animistic belief system which stresses respect for the land and its resources. During migrations, the Nenets placed sacred items like bear skins, religious figures, coins and more on a holy sleigh. The contents of this sacred sleigh are only unpacked during special occasions or for religious rituals (like sacrifices). However, only esteemed elders are allowed to unpack the sacred sleigh.[8] They had a clan-based social structure. The Nenets shaman is called a Tadibya.

After the Russian Revolution, their culture suffered due to the Soviet collectivisation policy. The government of the Soviet Union tried to force the nomadic Samoyeds to settle down permanently. They were forced to settle in villages and their children were educated in state boarding schools, which resulted in erosion of their cultural identity. Many, especially in the Nenets Autonomous Okrug lost their mother tongue and became assimilated. Since the 1930s, a few Nenets have expressed themselves professionally through cultural media. For instance, Tyko Vylka and Konstantin Pankov became well-known painters. Anna Nerkagi is one of the most celebrated Nenets writers. Yuri Vella, though living as a reindeer herder, has become the first writer in the Forest Nenets language.

Environment

Environmental damage to the Nenets' ancestral land is significant due to industrialisation of their land, colonization and climate change.[9] Because of the expansive gas and oil industry, reindeer pastures are shrinking, and some regions, such as the Yamal Peninsula are overgrazed, further endangering the Nenets way of life. The effects of global warming and climate change on nomadic Nenets reindeer herders have been documented, as certain lands they need to cross to follow migration patterns are only accessible during winter.[10] Earlier spring melts compounded by delayed autumn freeze, affect the ability of reindeer and herders to traverse the frozen tundra.[11] Arkhangelsk-based Leonid Zubov has documented how this restricts Nenets people's access to medical facilities, causing them to wait until the next snow season for medical attention.[12]

Notable Nenets

- Tyko Vylka (1886–1960), painter

- Konstantin Pankov (1910–1942), painter (Mansi mother)

- Anastasia Lapsui (b. 1944), film director, screenwriter

- Yuri Vella (1948–2013), writer, poet, environmentalist, social activist

- Anna Nerkagi (b. 1952), writer, novelist, social activist

See also

- Music of Nenetsia

- Nga (god)

- Siberian minorities in the Soviet era

- Pole worship

References

- "Информационные материалы об окончательных итогах Всероссийской переписи населения 2010 года". gks.ru. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- (Ukrainian)

- Little people of the North and the Far East (МАЛЫЕ НАРОДЫ СЕВЕРА И ДАЛЬНЕГО ВОСТОКА). Multinational Petersburg. 18 July 2015

- "Nenets: A language of Russian Federation". Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Ethnologue. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- Janhunen, Juha; Salminen, Tapani. "UNESCO Red Book on Endangered Languages: Northeast Asia". Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- Games, Alex (2007), Balderdash & piffle : one sandwich short of a dog's dinner, London: BBC, ISBN 978-1-84607-235-2

- Heptner, V. G. & Naumov, N., P. (editors) Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol.II Part 1a, SIRENIA AND CARNIVORA (Sea cows; Wolves and Bears), Science Publishers, Inc. USA. 1998. ISBN 1-886106-81-9

- Winston, Robert, ed. (2004). Human: The Definitive Guide. New York: Dorling Kindersley. p. 428. ISBN 0-7566-0520-2.

- Forbes, Bruce C. (1999). "Land use and climate change on the Yamal Peninsula of north-west Siberia: some ecological and socio-economic implications". Polar Research. 18 (2): 367–373. doi:10.1111/j.1751-8369.1999.tb00316.x.

- Davydov, Alexander N.; Mikhailova, Galina V. (2011). "Climate change and consequences in the Arctic: perception of climate change by the Nenets people of Vaigach Island". Global Health Action. 4. doi:10.3402/gha.v4i0.8436. PMC 3217310. PMID 22091216.

- "The Nenets of Siberia". Survival International. Survival International. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- Berg-Nordlie, Mikkel: Upcoming Deluge or False Prophecy? Climate Change Debates in the Russian North Archived 2011-04-30 at the Wayback Machine The NIBR International Blog, 16.06.2011

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 118.

External links

- Aging in the Nenets community

- UNESCO Red Book on endangered languages

- Jarkko Niemi: The types of the Nenets songs. 1997

- Minority languages of Russia on the Net

- The Red Book of the peoples of the Russian Empire

- Article on Nenets religion, culture and history

- Historic-demographic note on the Nenets of the Komi Republic

- BBC: Nenets Tribe

- Photos of Nenets reindeer herders

- BBC Living with Nomads 2/3 Siberia