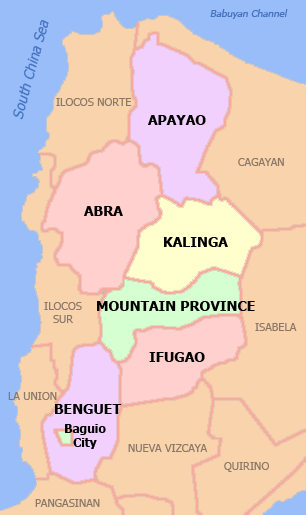

Ethnicities of the Philippine Cordilleras

There are nine main ethnolinguistic groups in the Cordilleras. The Cordillera Region is located in Luzon and is the largest region in the Philippines. It has a distinct culture from the rest of the country and each town has its own dialect.

Bontoks

The Bontok ethnolinguistic group can be found in the central and east portions of the Mountain Province. It mainly consists of the Balangaos and Gaddangs, with a significant portion who identify as part of the Kalinga group. The Bontok live in a mountainous territory, particularly close to the Chico River and its tributaries.[1]

Mineral resources (gold, copper, limestone, gypsum) can be found in the mountain areas. Gold, in particular, has been traditionally extracted from the Bontoc municipality. The Chico River provides sand, gravel and white clay, while the forests of Barlig and Sadanga within the area have rattan, bamboo and pine trees.[1]

Bontoks have three different indigenous housing structures: the residence place of the family (katyufong), the dormitories for females (olog), and the dormitories for males (ato/ator). Different structures are mostly associated with agricultural needs, such as rice granaries (akhamang) and pigpens (khongo).

Traditionally, all structures have inatep, cogon grass roofs. Bontok houses also have numerous utensils, tools, and weapons: like cooking tools; agricultural tools like bolos, trowels, and plows, bamboo or rattan fish traps. Weapons include battleaxes (pin-nang/pinangas), knives and spears (falfeg, fangkao, sinalawitan), and shields (kalasag).[1]

Music is also important to Bontoc life, and is usually played during ceremonies. Songs and chants are accompanied by nose flutes (lalaleng), gongs (gangsa), bamboo mouth organ (affiliao), and Jew's harp (ab-a-fiw). Wealthy families make use of jewelry, which are commonly made of gold, glass beads, agate beads (appong), or shells, to show their status.[1]

The Bontok take pride in their kinship ties and oneness as a group (sinpangili) based on affiliations, history together against intruders, and community rituals for agriculture and matters which affect the entire province, like natural disasters. Kinship groups have two main functions: controlling property and regulating marriage. However, they are also important for the mutual cooperation of the group's members.[1]

There are generally three social classes in Bontok society, the kakachangyan (rich), the wad-ay ngachanna (middle-class), and the lawa (poor). The rich sponsor feasts, and assist those in distress, as a demonstration of their wealth. The poor usually work as sharecroppers or as laborers for the rich.[1]

Men wear g-strings (wanes) and a rattan cap (suklong). Women wear skirts (tapis).[1]

Anthropologists believe that the Bontok descended from Indonesian and Malay immigrants, however, Bontoks believe that they have lived in their present area since time immemorial. Today, they are distributed all over the Philippines. They are the second largest group in the Mountain Province.[1]

The Bontok culture hero Lumawig instituted their ator, a political institution identified with a ceremonial place adorned with headhunting skulls. Lumawig also gave the Bontok their irrigation skills, Taboos, rituals and ceremonies after he descended from the sky (chayya) and married a Bontok girl. Each ator has a council of elders, called ingtugtukon, who are experts in custom laws (adat). Decisions are by consensus.[1]

Intutungcho (the one above), or Kufunian, is their supreme deity. Lumawig is his son.[1]

Ibaloys

The Ibaloy group inhabits the southeastern part of Benguet Province. The area is rich in mineral resources like copper, gold, pyrite, and limestone. Plants and animals are also abundant in the forests and mountain areas, and there is an extensive water system that includes the Bued River, Agno River, and Amburayan River. Mount Pulag, the second highest mountain of the Philippines, is found in their territory and is a culturally important area as well, considered the place where spirits join their ancestors.[2]

The Ibaloy are distributed in the mountain valleys and settlements. Their language is called either Inibaloi or Nabaloi. Their ancestors are likely to have originated from the Lingayen and Ilocos coasts, who then migrated into the Southern Cordillera range before settling.[2]

Ibaloy society is composed of the rich (baknang) and three poor classes, the cowhands (pastol), farmhands (silbi), and non-Ibaloy slaves (bagaen).[2]

The Ibaloy have a rich material culture, most notably their mummification process, which makes use of saltwater to prevent organ decomposition. Pounded guava and patani leaves are applied to the corpse to prevent maggot or worm infestation while the body dries, the process taking anywhere from two months to even a year until the body is hardened.[2]

The Ibaloy build their houses (balai or baeng) near their farms. These are usually built on five foot posts (tokod) and contain only one room with no windows. Pine trees are usually used to build the houses, especially for wealthy families, while bark bamboo for floors and walls, and cogon grass for roofs (atup), are used by the poor. For cooking, they use pots are made of copper (kambung), and food compartments (shuyu) and utensils made of wood. Baskets and coconut shells are also used as containers. A wooden box filled with soil serves as the cooking place (Shapolan), and three stones as the stove (shakilan). Traditional weapons of the Ibaloys are the spear (kayang), shield (kalasai), bow and arrow (bekang and pana), and war club (papa), though they are rarely used in present times. The Ibaloy also employ cutting tools like knives, farm tools, and complete pounding implements for rice: mortars (dohsung), which are round or rectangular for different purposes, and pestles (al-o or bayu)of various sizes, carved from sturdy tree trunks and pine branches. Their rice winnower (dega-o or kiyag) are made of bamboo or rattan.[2]

Music is also important among the Ibaloy, with the Jew's harp (kodeng), nose flute (kulesheng), native guitar (kalsheng or Kambitong), bamboo striking instruments, drums (solibao), gongs (kalsa), and many others. They are considered sacred, and must always be played for a reason, such as a cañao feast.[2]

Men wear a g-string (kuval), and the wealthy include a dark blue blanket (kulabaw or alashang) while the rest use a white one (kolebao dja oles). Women wear a blouse (kambal) and a skirt (aten or divet). Gold-plated teeth covers (shikang), copper leglets (batding), copper bracelets (karing), and ear pendants (tabing) reflect the benefits of mining for gold and copper. Lode or placer mining is followed by ore crushing using a large flat stone (gai-dan) and a small one (alidan). The gold in the resultant fine sand is then separated (sabak) in a water trough (dayasan). The gold is then melted into cakes.[2]

Older Ibaloy people may have tattooed arms as a sign of prestige.[2]

The Ibaloy believe in two kinds of spirits (anitos). The nature spirits are associated with calamities, while the ancestral ones (ka-apuan) make their presence known in dreams or by making a family member sick.[2]

Ikalahans

The Ikalahan is a small group distributed amongst the mountain ranges of Sierra Madre, the Caraballo, and the eastern part of the Cordillera mountain range. The main population resides in the Nueva Vizcaya province, with Kayapa as the center. They are considered to be part of the Igorot (mountain people) but distinguish themselves with the name Ikalahan, the name taken from the forest trees that grow in the Caraballo Mountain.[3]

They are among the least studied ethnic groups, thus their early history is unknown. However, Felix M. Keesing suggests that, like other groups in the mountains, they fled from the lowlands to escape Spanish persecution.[3]

There are two classes of society, the rich (baknang or Kadangyan) and the poor (biteg or abiteng). Ikalahan practice swidden (“slash-and-burn”) farming (inum-an) of camote, and yam (gabi).[3]

Ikalahan houses, traditionally made for one nuclear family, have of reeds (pal-ot) or cogon (gulon) for roofs, barks or slabs of trees for the walls, and palm strips (balagnot) for the floor. The houses are traditionally rectangular and raised from the ground 3–5 feet, with one main room for general activities and one window and door. There is usually a separate room (duwag) for visitors or single family members only, opposite the kitchen area. Two stone stoves are on a hearth, one cooks meals for the pigs in a copper cauldron (gambang), the other for the household. Shelves (pagyay) keep household utensils, including wooden bowls (duyo) and camote trays (ballikan or tallaka) made of rattan. Camote peelings (dahdah) or rejects (padiw) are fed to the pigs, which are herded under the living area or in a sty near the house.[3]

The Ikalahan, like many ethnic groups, enjoy using musical instruments in celebration, most of which are made out of bamboo. Gongs (gangha) are the primary instruments used, and are complemented by drums. They also use a native guitar, or galdang, and a vibrating instrument called the pakgong played by striking, besides the Jew's harp (Ko-ling).[3]

For clothing, Ikalahan men wear a loincloth or G-string (kubal), and carry backpacks (akbot) made out of deer hide. Men almost always carry a bolo when leaving the house. Women wear woven skirts (lakba) around the waist, made up of flaps of different color combinations. They wear a blouse from the same material. They use a basket (kayabang) carried on the back for carrying their farming tools. Body ornaments include brass coiled bracelets (gading or batling).[3]

Society authority rests with the elders (nangkaama), with the tongtongan conference being the final say in matters. Feats include the keleng for healing the sick, ancestor remembrance, and other occasions. A sponsor may also hold a ten-day feast, padit.[3]

Ifugaos

Ifugaos, commonly known as Igorots in Filipino, are an ethnolinguistic group majorly found in Ifugao province, which is located in the heart of Cordillera. The province is one of the smallest provinces in the Philippines with an area of only 251,778 hectares, or about 0.8% of the total Philippine land area. It has a temperate climate and is rich in mineral and forest products.[4]

Wet rice terraces characterize their farming, supplemented with swidden farming of camote.[4] They are famous for their Banaue Rice Terraces, which became one of the main tourist attractions in the country.

The term Igorot or Ygolote was the term used by Spanish conquerors for mountain people. The Ifugaos, however, prefer the name Ifugao which came from the word ipugo(human beings in English). Although a majority of them already converted to Roman Catholic from their original animistic religion, from their mythology, they believed that they descended from Wigan and Bugan, who are the children of Bakkayawan and Bugan of the Skyworld (Kabunyan). Henry Otley Beyer thought the Ifugaos originated from Indo-China 2,000 years ago. Felix Keesing thought they came from the Magat area because of the Spanish, hence the rice terraces are only a few hundred years old. The Ifugao popular epic, The Hudhud of Dinulawan and Bugan of Gonhadan support this interpretation. Dulawan thought the Ifugaos came from the western Mountain Province due to similarities with Kankana-eys culture and language.[4]

As of 1995, the population of the Ifugaos was counted to be 131,635. Although the majority of them are still in Ifugao province, some of them already transferred to Baguio City, where they worked as woodcarvers, and to other parts of the Cordillera region.[4]

They are divided into subgroups based on the differences in dialects, traditions, and design/color of costumes. The main subgroups are Ayangan, Kalangaya, and Tuwali. Furthermore, the Ifugao society is divided into 3 social classes: the kadangyans or the aristocrats, the tagus or the middle class, and the nawotwots or the poor ones. The kadangyans sponsor the prestige rituals called hagabi and uyauy and this separates them from the tagus who cannot sponsor feasts but are economically well off. The nawotwots are those who have limited land properties and are usually hired by the upper classes to do work in the fields and other services.[4]

The Ifugaos host a number of similarities with the Bontocs in terms of agriculture, but the Ifugao tend to have more scattered settlements, and recognize their affiliation mostly towards direct kin in households closer to their fields [5]

From a person's birth to his death, the Ifugaos follow a lot of traditions. Pahang and palat di oban are performed to a mother to ensure safe delivery. After delivery, no visitors are allowed to enter the house until among is performed when the baby is given a name. Kolot and balihong are then performed to ensure the health and good characteristics of the boy or the girl, respectively. As they grow older, they sleep in exclusive dormitories because it is considered indecent for siblings of different genders to sleep in the same house. The men are the ones who hunt, recite myths, and work in the fields. Women also work in the fields, aside from managing the homes and reciting ballads. Betrothals are also common, especially among the wealthy class; and like other Filipinos they perform several customs in marriage like bubun (providing a pig to the woman's family). Lastly, the Ifugaos do not mourn for the elderly who died, nor for the baby or the mother who died in a conception. This is to prevent the same event from happening again in the family. Also, the Ifugaos believe in life after death so those who are murdered are given a ritual called opa to force their souls into the place where his ancestors dwell.[4]

Ifugao houses (Bale) are built on f posts 3 meters from the ground, and consist of one room, a front (panto) and back door (awidan), with a detachable ladder (tete) to the front door. Temporary huts (abong ) give shelter to workers in the field or forest. Rice granaries (alang) are protected by a wooden guardian (bulul).[4]

Men wear a loincloth (wanoh) while women wear a skirt (ampuyo). On special occasions, men wear a betel bag (pinuhha) and their bolo (gimbattan). Musical instruments include gongfs (gangha), a wooden instrument that is struck with another piece of wood (bangibang), a thin brass instrument that is plucked (bikkung), stringed instruments (ayyuding and babbong), nose flutes (ingngiing) and mouth flutes (kupliing or ippiip).[4]

Criminal cases are tried by ordeal. They include duels (uggub/alao), wrestling (bultong), hot bolo ordeal and boiling water ordeal (da-u). Ifugaos believe in 6 worlds, Skyworld (Kabunyan), Earthworld (Pugaw), Underworld (Dalom), the Eastern World (Lagud), the Western World (Daya), and the Spiritual World (Kadungayan). Talikud carries the Earthworld on his shoulders and cause earthquakes. The ifugaos include nature and ancestor worship, and participate in rituals (baki) presided over by a mumbaki. Priests (munagao and mumbini) guide the people in rites for good fortune.[4]

Isnegs

The Isnegs are native in Apayao province, which was formerly a sub-province of Mountain Province, but are also found in portions of Abra, Ilocos Norte, & Kalinga. Apayao has an area of 397,720 hectares and is typographically divided into two parts: the Upper Apayao that is mountainous, and the Lower Apayao that is generally flat with rolling mountains and plateaus.[6]

In 1923, they were the last ethnic group to be conquered by the American colonialists. Before, they had no collective name. Instead, they referred to themselves based on their residence or whether they lived: upstream (Imandaya) or downstream (Imallod). At present, they are commonly known as Isnegs, which came from an Ilocano word itneg that means Inhabitants of the Tineg River. Some of them, however, still call themselves as Apayaos. Majority of them live along the Apayao River-Abulog River, Matalag River, and the small rivers on the hillsides of Ilocos Norte and Abra.[6]

Because there was no political or ward system, the kinship groups and family clans became the central social organizations and were usually led by the husbands. Polygamy is allowed, but depends on the capacity of the husband to support the family. Like other ethnic groups, they also follow a lot of taboos. These taboos vary from place to place. A pregnant woman, for example, is discouraged to eat some kinds of sugarcane, banana, and the soft meat of sprouting coconut to have a normal conception. In the past, twins were also believed to be unlucky, so whenever twins were born, they would let the weaker twin die. Also, if the mother dies upon giving birth, the child is also left to die and is usually buried with the mother. The Isnegs don’t follow rituals on the adolescence of the child. They, however, have rituals on marriage, like the amoman (or the present-day pamamanhikan), and death, like the mamanwa which is done by the widowers.[6]

Isneg houses (balay) are two-story, one-room structures built on 4 corner posts with an entrance reached by a ladder. The open space below (linong or sidong) includes a small shed (abulor) for jars of basi. The bamboo pigpen(dohom) is nearby. Rice granaries (alang) are also made on four posts that include a circular and flat rat shield. Temporary buildings associated with upland and swidden farming are called sixay. Their bolo (badang) and axe (aliwa) are important tools. They are also expert fishermen.[6]

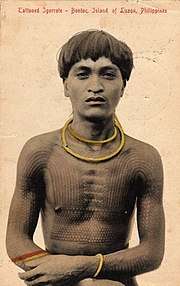

The Isnegs are aesthetically-inclined. In ceremonies, women wear a lot of colourful ornaments and clothings, and men wear G-strings (usually of blue color), abag, and bado (upper garment). Men don’t wear pendants but they wear an ornament called sipattal, made of shells and beads, used only on special occasions. They also practice tattooing which is done by rubbing soot on the wounds caused by the needles.[6]

A group of brave men form the leadership (mengals) headed by the bravest (kamenglan). They are animistic, believing in several good and bad spirits. A woman shaman (Anituwan) performs ceremonies on request. These include the say-am and pildap.[6]

Kalingas

The Kalingas are mainly found in Kalinga province which has an area of 3,282.58 sq. km. Some of them, however, already migrated to Mountain Province, Apayao, Cagayan, and Abra. As of 1995, they were counted to be 105,083, not including those who have migrated outside the Cordillera region.[7]

Kalinga territory includes floodplains of Tabuk, and Rizal, plus the Chico River. Gold and copper deposits are common in Pasil and Balbalan. Tabuk was settled in the 12th century, and from there other Kalinga settlements spread, practicing wet rice (papayaw) and swidden (uwa) cultivation. Kalinga houses (furoy, buloy, fuloy, phoyoy, biloy)are either octagonal for the wealthy, or square, and are elevated on posts (a few as high as 20-30 feet), with a single room. Other building include granaries (alang) and field sheds (sigay).[7][8]

The name Kalinga came from the Ibanag and Gaddang term kalinga, which means headhunter. Edward Dozier divided Kalinga geographically into three sub-cultures and geographical position: Balbalan (north); Pasil, Lubuagan, and Tinglayan (south); and Tanudan (east). Teodoro Llamzon divided the Kalinga based on their dialects: Guinaang, Lubuagan, Punukpuk, Tabuk, Tinglayan, and Tanudan.[7]

Like other ethnic groups, families and kinship systems are also important in the social organizations of Kalingas. They are, however, stratified into two economic classes only which are determined by the number of their rice fields, working animals, and heirlooms: the kapos (poor) and the baknang (wealthy). The wealthy employ servants (poyong). Politically, the mingol and the papangat have the highest status. The mingols are those who have killed many in headhunting and the papangats are those former mingols who assumed leadership after the disappearance of headhunting. They are usually the peacemakers, and the people ask advice from them, so it is important that they are wise and have good oratorical ability.[7]

Like the other ethnic groups, they also follow a lot of customs and traditions. For example, pregnant women and their husbands are not allowed to eat beef, cow’s milk, and dog meat. They must also avoid streams and waterfalls as these cause harm to unborn children. Other notable traditions are the ngilin (avoiding the evil water spirit) and the kontad or kontid (ritual performed to the child to avoid harms in the future). Betrothals are also common, even as early as birth, but one may break this engagement if he/she is not in favour of it. Upon death, sacrifices are also made in honour of the spirit of the dead and kolias is celebrated after one year of mourning period.[7]

They use the uniquely shaped Kalinga head ax (sinawit), bolo (gaman/badang), spears (balbog/tubay/say-ang), and shields (kalasag). They also carry a rattan backpack (pasiking) and betel nut bag (buyo).[7]

Kalinga men wear ba-ag (loincloths) while the women wear saya (colourful garment covering the waist down to the feet). The women are also tattooed on their arms up to their shoulders and wear colourful ornaments like bracelets, earrings, and necklaces, especially on the day of festivities. Heirlooms include Chinese plates (panay), jars (gosi), and gongs (gangsa). Key dances include the courtship dance (salidsid) and war dance (pala-ok or pattong).[7]

The Kalinga belief in a Supreme Being, Kabuniyan, the creator and giver of life, who once lived amongst them. They also believe in numerous spirits and deities, including those associated with nature (pinaing and aran), and dead ancestors (kakarading and anani). The priestess (manganito, mandadawak, or mangalisig) communicate with these spirits.[7]

Northern Kankana-eys

The Northern Kankana-eys live in Sagada and Besao, west of Mountain province, and constitute a linguistic group. They are referred to with the generic name Igorot, but call themselves Aplai. H. Otley Beyer believed they originated from a migrating group from Asia who landed on the coasts of Pangasinan before moving to Cordillera. Beyer's theory has since been discredited, and Felix Keesing speculated the people were simply evading the Spanish. Their smallest social unit is the sinba-ey, which includes the father, mother and children. The sinba-eys make up the dap-ay/ebgan which is the ward. Their society is divided into two classes: the kadangyan (rich), who are the leaders and who inherit their power through lineage or intermarriage, and the kado (poor). They practice bilateral kinship.[9]

The Northern Kankana-eys believe in many supernatural beliefs and omens, and in gods and spirits like the anito (soul of the dead) and nature spirits.[9]

They also have various rituals, such as the rituals for courtship and marriage and death and burial. The courtship and marriage process of the Northern Kankana-eys starts with the man visiting the woman of his choice and singing (day-eng), or serenading her using an awiding (harp), panpipe (diw-as), or a nose flute (kalelleng). If the parents agree to their marriage, they exchange work for a day (dok-ong and ob-obbo), i.e. the man brings logs or bundled firewood as a sign of his sincerity, the woman works on the man’s father’s field with a female friend. They then undergo the preliminary marriage ritual (pasya) and exchange food. Then comes the marriage celebration itself (dawak/bayas)inclusive of the segep (which means to enter), pakde (sacrifice), betbet (butchering of pig for omens), playog/kolay (marriage ceremony proper), tebyag (merrymaking), mensupot (gift giving), sekat di tawid (giving of inheritance), and buka/inga, the end of the celebration. The married couple cannot separate once a child is born, and adultery is forbidden in their society as it is believed to bring misfortune and illness upon the adulterer. On the other hand, the Northern Kankana-eys honor their dead by keeping vigil and performing the rituals sangbo (offering of 2 pigs and 3 chickens), baya-o (singing of a dirge by three men), menbaya-o (elegy) and sedey (offering of pig). They finish off the burial ritual with dedeg (song of the dead), and then, the sons and grandsons carry the body to its resting place.[9]

The Northern Kankana-eys have rich material culture among which is the four types of houses: the two-story inhagmang, binang-iyan, tinokbobo and the elevated tinabla. Other buildings include the granary (agamang), male clubhouse (dap-ay or abong), and female dormitory (ebgan). Their men wear rectangular woven cloths wrapped around their waist to cover the buttocks and the groin (wanes). The women wear native woven skirts (pingay or tapis) that cover their lower body from waist to knees and is held by a thick belt (bagket).[9]

Their household is sparsely furnished with only a bangkito/tokdowan, po-ok (small box for storage of rice and wine), clay pots, and sokong (carved bowl). Their baskets are made of woven rattan, bamboo or anes, and come in various shapes and sizes.[9]

The Kankana-eys have three main weapons, the bolo (gamig), the axe (wasay) and the spear (balbeg), which they previously used to kill with but now serve practical purposes in their livelihood. They also developed tools for more efficient ways of doing their work like the sagad (harrow), alado (plow dragged by carabao), sinowan, plus sanggap and kagitgit for digging. They also possess Chinese jars (gosi) and copper gongs (gangsa).[9]

For a living, the Northern Kankana-eys take part in barter and trade in kind, agriculture (usually on terraces), camote/sweet potato farming, slash-and-burn/swidden farming, hunting, fishing and food gathering, handicraft and other cottage industry. They have a simple political life, with the Dap-ay/abong being the center of all political, religious and socials activities, with each dap-ay experiencing a certain degree of autonomy. The council of elders, known as the Amam-a, are a group of old, married men expert in custom law and lead in the decision-making for the village. They worship ancestors (anitos) and nature spirits.[9]

Southern Kankana-eys

The Southern Kankana-eys are one of the ethnolinguistic groups in the Cordillera. They live in the mountainous regions of Mountain Province and Benguet, more specifically in the municipalities of Tidian, Bauko, Sabangan, Bakun, Kibungan and Mankayan. They are predominantly a nuclear family type (sinbe-ey,buma-ey, or sinpangabong), which are either patri-local or matri-local due to their bilateral kinship, composed of the husband, wife and their children. The kinship group of the Southern Kankana-eys consists of his descent group and, once he is married, his affinal kinsmen. Their society is divided into two social classes based primarily on the ownership of land: The rich (baknang) and the poor (abiteg or kodo). The baknang are the primary landowners to whom the abiteg render their services to. The Mankayan Kankana-eys, however, has no clear distinction between the baknang and the abiteg and all have equal access to resources such as the copper and gold mines.[10]

Contrary to popular belief, the Southern Kankana-eys do not worship idols and images. The carved images in their homes only serve decorative purposes. They believe in the existence of deities, the highest among which is Adikaila of the Skyworld whom they believe created all things. Next in the hierarchy is the Kabunyan, who are the gods and goddesses of the Skyworld, including their teachers Lumawig and Kabigat. They also believe in the spirits of ancestors (ap-apo or kakkading), and the earth spirits they call anito. They are very superstitious and believe that performing rituals and ceremonies help deter misfortunes and calamities. Some of these rituals are pedit (to bring good luck to newlyweds), pasang (cure sterility and sleeping sickness, particularly drowsiness) and pakde (cleanse community from death-causing evil spirits).[10]

The Southern Kankana-eys have a long process for courtship and marriage which starts when the man makes his intentions of marrying the woman known to her. Next is the sabangan, when the couple makes their wish to marry known to their family. The man offers firewood to the father of the woman, while the woman offers firewood to the man’s father. The parents then talk about the terms of the marriage, including the bride price to be paid by the man’s family. On the day of the marriage, the relatives of both parties offer gifts to the couple, and a pig is butchered to have its bile inspected for omens which would show if they should go on with the wedding. The wedding day for the Southern Kankana-eys is an occasion for merrymaking and usually lasts until the next day. Though married, the bride and groom are not allowed to consummate their marriage and must remain separated until such a time that they move to their own separate home.[10]

The funeral ritual of the Southern Kankana-eys lasts up to ten days, when the family honors their dead by chanting dirges and vigils and sacrificing a pig for each day of the vigil. Five days after the burial of the dead, those who participated in the burial take a bath in a river together, butcher a chicken, then offer a prayer to the soul of the dead.[10]

The Southern Kankana-eys have different types of houses among which are binang-iyan (box-like compartment on 4 posts 5 feet high), apa or inalpa (a temporary shelter smaller than bingang-iyan), inalteb (has a gabled roof and shorter eaves allowing for the installation of windows and other opening at the side), allao (a temporary built in the fields), at-ato or dap-ay (a clubhouse or dormitory for men, with a long, low gable-roofed structure with only a single door for entrance and exit), and ''ebgang or olog (equivalent to the at-ato, but for women). Men traditionally wear a G-string (wanes) around the waist and between the legs which is tightened at the back. Both ends hang loose at the front and back to provide additional cover. Men also wear a woven blanket for an upper garment and sometimes a headband, usually colored red like the G-string. The women, on the other hand, wear a tapis, a skirt wrapped around to cover from the waist to the knees held together by a belt (bagket) or tucked in the upper edges usually color white with occasional dark blue color. As adornments, both men and women wear bead leglets, copper or shell earrings and beads of copper coin. They also sport tattoos which serve as body ornaments and “garments”.[10]

Southern Kankana-eys are economically involved in hunting and foraging (their chief livelihood), wet rice and swidden farming, fishing, animal domestication, trade, mining, weaving and pottery in their day-to-day activities to meet their needs. The leadership structure is largely based on land ownership, thus the more well-off control the community's resources. The village elders (lallakay/dakay or amam-a) who act as arbiters and jurors have the duty to settlements between conflicting members of the community, facilitate discussion among the villagers concerning the welfare of the community, and lead in the observance of rituals. They also practice trial by ordeal. Native priests (mansip-ok, manbunong, and mankotom) supervise rituals, read omens, heal the sick, and remember genealogies.[10]

Gold and copper mining is abundant in Mankayan. Ore veins are excavated, then crushed using a large flat stone (gai-dan). The gold is separated using a water trough (sabak and dayasan), then melted into gold cakes.[10]

Musical instruments include the tubular drum (solibao), brass or copper gongs (gangsa), Jew's harp (piwpiw), nose flute (kalaleng), and a bamboo-wood guitar (agaldang).[10]

There is no more pure Southern Kankana-ey culture because of culture change that modified the customs and traditions of the people. The socio-cultural changes are largely due to a combination of factors which include the change in the local government system when the Spaniards came, the introduction of Christianity, the education system that widened the perspective of the individuals of the community, and the encounters with different people and ways of life through trade and commerce.[10]

Tingguans/Itnegs

The Tingguinians live in the mountainous area of Abra in northwestern Luzon who descended from immigrants from Kalinga, Apayao, and the Northern Kankana-ey. They are large in stature, have mongoloid eyes, aquiline nose, and are effective farmers. They refer to themselves as Itneg, though the Spaniards called them Tingguian when they came to the Philippines because they are mountain dwellers. The Tingguians are further divided into nine distinct subgroups which are the Adasen, Mabaka, Gubang, Banao, Binongon, Danak, Moyodan, Dawangan, and Ilaud. Wealth and material possessions (such as Chinese jars, copper gongs called gangsa, beads, rice fields, and livestock) determine the social standing of a family or person, as well as the hosting of feasts and ceremonies. Despite the divide of social status, there is no sharp distinction between rich (baknang) and poor. Wealth is inherited but the society is open for social mobility of the citizens by virtue of hard work. Medium are the only distinct group in their society, but even then it is only during ceremonial periods.[11]

The Itnegs’ marriage are arranged by the parents and are usually between distant relatives in order to keep the family close-knit and the family wealth within the kinship group. The parents select a bride for their son when he is six to eight years old, and the proposal is done to the parents of the girl. If accepted, the engagement is sealed by tying beads around the girl's waist as a sign of engagement. A bride price (pakalon) is also paid to the bride's family, with an initial payment and the rest during the actual wedding. No celebration accompanies the Itneg wedding and the guests leave right after the ceremony.[11]

The females dress in a wrap-around skirt (tapis) that reaches to the knees and fastened by an elaborately decorated belt. They also wear short sleeved jacket on special occasions. The men, on the other hand, wear a G-string (ba-al) made of woven cloth (balibas). On special occasions, the men also wear a long-sleeved jacket (bado). They also wear a belt where they fasten their knife and a bamboo hat with a low, dome-shaped top. Beads are the primary adornment of the Tingguians and a sign of wealth. Also, tattooing is commonly practiced. The Tingguians have two general types of housing. The first is a 2–3 room-dwelling surrounded by a porch and the other is a one-room house with a porch in front. Their houses are usually made of bamboo and cogon. A common feature of a Tingguian home with wooden floors is a corner with bamboo slats as flooring where mothers usually give birth. Spirit structures include balawa built during the say-ang ceremony, sangasang near the village entrance, and aligang containing jars of basi.[11]

The Tingguians use weapons for hunting, headhunting, and building a house, among others. Some examples of their weapons and implements are the lance or spear (pika), shield (kalasag), head axe (aliwa). Foremost among all these weapons and implements is the bolo which the Tangguians are rarely seen without.[11]

The traditional leadership in the Tangguian community is held by panglakayen (old men), who compose a council of leaders representing each purok or settlement. The panglakayen are chosen for their wisdom and eagerness to protect the community's interest. Justice is governed by custom (kadawyan) and trial by ordeal. Head taking was finally stopped through peace pacts (kalon).[11]

The Itnegs are religious beings who believe in the existence of numerous supernatural powerful beings. They believe in spirits and deities, the greatest of which they believe to be Kadaklan who lives up in the sky and who created the earth, the moon, the stars, and the sun. The Itnegs believe in life after death, which is in a place they call maglawa. They take special care to clean and adorn their dead to prepare them for the journey to maglawa. The corpse is placed in a death chair (sangadel) during the wake.[11]

The Tingguians still practice their traditional ways, including wet rice and swidden farming. Socio-cultural changes started when the Spanish conquistadors ventured to expand their reach to the settlements of Abra. The Spaniards brought with them their culture some of which the Tangguians borrowed. More changes in their culture took place with the coming of the Americans and the introduction of education and Catholic and Protestant proselytization.[11]

See also

References

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "1 The Bontoks". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 1–27. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "2 The Ibaloys". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 28–51. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "3 The Ikalahans". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 52–69. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "4 The Ifugaos". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 71–91. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Goda, Toh (2001). Cordillera: Diversity in Culture Change, Social Anthropology of Hill People in Northern Luzon, Philippines. Quezon City, Philippines: New Day Publishers.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "5 The Isnegs". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 92–114. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "5 The Kalingas". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 115–135. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Scott, William Henry (1996). On the Cordilleras: A look at the peoples and cultures of the Mountain Province. 884 Nicanor Reyes, Manila, Philippines: MCS Enterprises, Inc. p. 16.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "7 The Northern Kankana-eys". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 136–155. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "8 The Southern Kankana-eys". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 156–175. ISBN 9789711011093.

- Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "9 The Tingguians/Itnegs". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 177–194. ISBN 9789711011093.

- “Cordillera Autonomous Region”. Nov 7, 2014. It’s More Fun in the Philippines.

- "Bontocs - Google Search". Google.com.ph. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- "Southern Kankanaeys - Google Search". Google.com.ph. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- "Bontocs - Google Search". Google.com.ph. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- "Bontocs - Google Search". Google.com.ph. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- "Bontocs - Google Search". Google.com.ph. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- "Bontocs - Google Search". Google.com.ph. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- "Bontocs - Google Search". Google.com.ph. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- "Bontocs - Google Search". Google.com.ph. Retrieved 31 December 2014.